Sykes–Picot Agreement

| Sykes–Picot Agreement | |

|---|---|

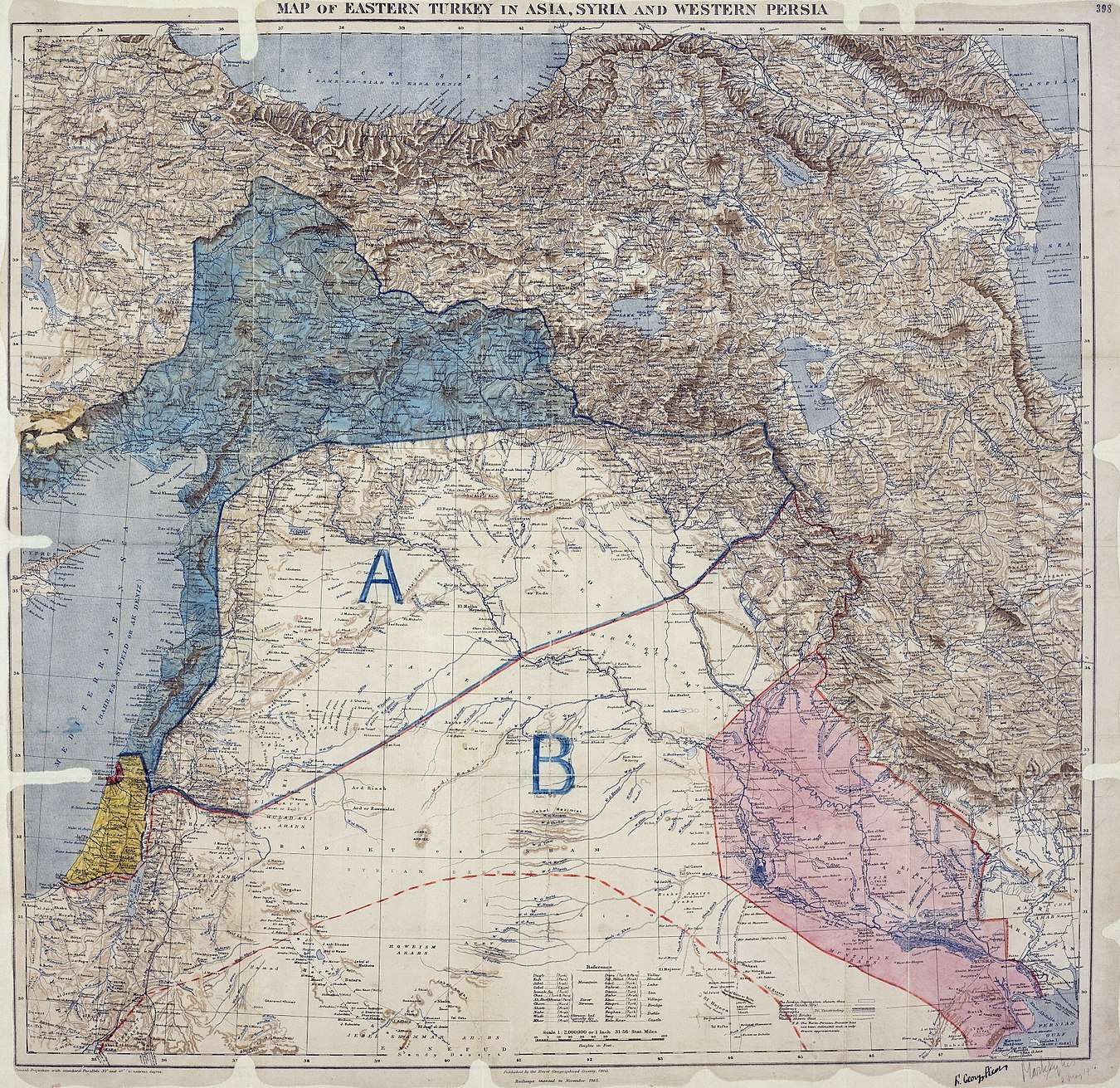

Sykes Picot Agreement Map, an enclosure in Paul Cambon's letter to Sir Edward Grey, 9 May 1916 | |

| Created | November 1915 – March 1916 |

| Presented | 23 November 1917 by the Russian Bolshevik government |

| Ratified | 16 May 1916 |

| Author(s) | |

| Signatories | |

| Purpose | Defining proposed spheres of influence and control in the Middle East should the Triple Entente succeed in defeating the Ottoman Empire |

The Sykes–Picot Agreement /ˈsaɪks

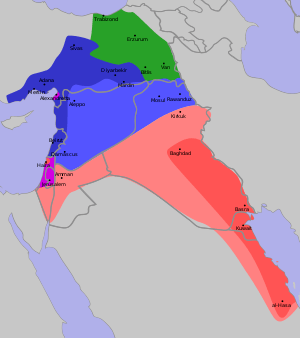

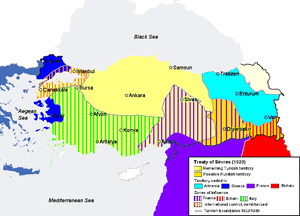

The agreement allocated to Britain control of areas roughly comprising the coastal strip between the Mediterranean Sea and the River Jordan, Jordan, southern Iraq, and an additional small area that included the ports of Haifa and Acre, to allow access to the Mediterranean.[8] France got control of southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq, Syria and Lebanon.[8] Russia was to get Istanbul, the Turkish Straits and Armenia.[8] The controlling powers were left free to determine state boundaries within their areas.[8] Further negotiation was expected to determine international administration in the "brown area" (an area including Jerusalem, similar to and smaller than Mandate Palestine), the form of which was to be decided upon after consultation with Russia, and subsequently in consultation with the other Allies, and the representatives of Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca.[8]

The agreement effectively divided the Ottoman Arab provinces outside the Arabian peninsula into areas of British and French control and influence.[9] In the Levant, it was initially used directly as the basis for the 1918 Anglo–French Modus Vivendi which agreed a framework for the Occupied Enemy Territory Administration. More broadly it was to lead, indirectly, to the subsequent partitioning of the Ottoman Empire following Ottoman defeat in 1918.

The Acre-Haifa zone was intended to be a British enclave in the North to enable access to the Mediterranean.[10] The British later gained control of the brown zone and other territory in 1920 and ruled it as Mandatory Palestine from 1923 until 1948. They also ruled Mandatory Iraq from 1920 until 1932, while the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon lasted from 1923 to 1946. The terms were negotiated by British diplomat Mark Sykes and a French counterpart, François Georges-Picot. The Tsarist government was a minor party to the Sykes–Picot agreement, and when, following the Russian Revolution, the Bolsheviks published the agreement on 23 November 1917, "the British were embarrassed, the Arabs dismayed and the Turks delighted".[11]

The agreement is seen by many as a turning point in Western and Arab relations. It negated the UK's promises to Arabs[12] made for a national Arab homeland in the area of Greater Syria, in exchange for supporting the British against the Ottoman Empire.

Motivation and negotiations

In the Constantinople Agreement earlier in 1915, following the start of naval operations in the run up to the Gallipoli Campaign the Russian Foreign Minister, Sergey Sazonov, wrote to the French and UK ambassadors and staked a claim to Constantinople and the Straits of Dardanelles. In a series of diplomatic exchanges over five weeks, the UK and France both agreed, while putting forward their own claims, to an increased sphere of influence in Iran in the case of the UK and to an annex of Syria (including Palestine) and Cilicia for France. The UK and French claims were both agreed, all sides also agreeing that the exact governance of the Holy Places was to be left for later settlement.[13] Although this agreement was ultimately never implemented because of the Russian revolution, it was in force as well as a direct motivation for it at the time the Sykes–Picot Agreement was being negotiated.

The report of the De Bunsen Committee, prepared to determine British wartime policy toward the Ottoman Empire, and submitted in June 1915,[14] concluded that, in case of the partition or zones of influence options, there should be a British sphere of influence that included Palestine while accepting that there were relevant French and Russian as well as Islamic interests in Jerusalem and the Holy Places.[15][16]

On 21 October 1915, Grey met Cambon and suggested France appoint a representative to discuss the future borders of Syria as Britain wished to back the creation of an independent Arab state. At this point Grey was faced with competing claims from the French and from Hussein and the day before had sent a telegram to Cairo telling the High Commissioner to be as vague as possible in his next letter to the Sharif when discussing the northwestern, Syrian, corner of the territory Husein claimed and left McMahon with "discretion in the matter as it is urgent and there is not time to discuss an exact formula", adding, "If something more precise than this is required you can give it."[17]

Mark Sykes had been dispatched on instructions of the War Office at the beginning of June to discuss the Committee's findings with the British authorities in the Near and Middle East and at the same time to study the situation on the spot. He went to Athens, Gallipoli, Sofia, Cairo, Aden, Cairo a second time and then to India coming back to Basra in September and a third time to Cairo in November (where he was appraised of the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence) before returning home on 8 December and finally delivering his report to the War Committee on 16 December.

The first meeting of the British interdepartmental committee headed by Sir Arthur Nicolson with François Georges-Picot had already taken place on 23 November 1915. Picot informed the Nicolson committee that France claimed the possession of land starting from where the Taurus Mts approach the sea in Cilicia, following the Taurus Mountains and the mountains further East, so as to include Diabekr, Mosul and Kerbela, and then returning to Deir Zor on the Euphrates and from there southwards along the desert border, finishing eventually at the Egyptian frontier. Picot, however, added that he was prepared "to propose to the French government to throw Mosul into the Arab pool, if we did so in the case of Bagdad".

A second meeting of the Nicolson committee with Picot took place on 21 December 1915 wherein Picot said that he had obtained permission to agree to the towns of Aleppo, Hama, Homs and Damascus being included in the Arab dominions to be administered by the Arabs. Although the French had scaled back their demands to some extent, the British also claimed to want to include Lebanon in the future Arab State and this meeting also ended at an impasse.

On 28 December, Mark Sykes informed Clayton that he had "been given the Picot negotiations". On 3 January 1916, an initialled memorandum was forwarded to the Foreign Office and after having been circulated for comments,[lower-alpha 1] An interdepartmental conference was convened by Nicolson on 21 January. On 16 January, Sykes told the Foreign office that he had spoken to Picot and that he thought Paris would be able to agree. Following the meeting, a final draft agreement was circulated to the cabinet on 2 February, the War Committee considered it on the 3rd and finally at a meeting on the 4th between Bonar Law, Mr. Chamberlain, Lord Kitchener and others where it was decided that:

M. Picot may inform his government that the acceptance of the whole project would entail the abdication of considerable British interests, but provided that the cooperation of the Arabs is secured, and that the Arabs fulfil the conditions and obtain the towns of Homs, Hama, Damascus and Aleppo, the British Government would not object to the arrangement. But, as the Blue Area extends so far Eastwards, and affects Russian interests, it would be absolutely essential that, before anything was concluded, the consent of Russia was obtained.

Picot was informed and 5 days later Cambon told Nicolson that "the French government were in accord with the proposals concerning the Arab question".[19]:100–102

Later, in February and March, Sykes and Picot acted as advisors to Sir George Buchanan and the French ambassador respectively, during negotiations with Sazonov. Eventually, Russia having agreed (for a price, as it obtained large portions of Ottoman territory in the bargain, including Constantinople and the Straits) on 26 April 1916, the final terms were sent by Paul Cambon, the French Ambassador in London, to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Edward Grey, on 9 May 1916, and ratified in Grey's reply on 16 May 1916.[20][21]

The Agreement in practice

Syria, Palestine and the Arabs

Asquith Government (1916)

While Sykes and Picot were in negotiations, discussions were proceeding in parallel between Cairo and Hussein (the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence); Hussein's reply of 1 January to McMahon's 14 December 1915 was received at the Foreign Office, McMahon’s cover stating:

Satisfactory as it may be to note his general acceptance for the time being of the proposed relations of France with Arabia, his reference to the future of those relations adumbrates a source of trouble which it will be wise not to ignore. I have on more than one occasion brought to the notice of His Majesty's Government the deep antipathy with which the Arabs regard the prospect of French Administration of any portion of Arab territory. In this lies considerable danger to our future relations with France, because difficult and even impossible though it may be to convince France of her mistake, if we do not endeavour to do so by warning her of the real state of Arab feeling, we may hereafter be accused of instigating or encouraging the opposition to the French, which the Arabs now threaten and will assuredly give.

After discussions, Grey instructed that the French be informed of the situation although Cambon did not take the matter that seriously.[19]:103–104

Hussein's letter of 18 February 1916 appealed to McMahon for £50,000 in gold plus weapons, ammunition and food claiming that Feisal was awaiting the arrival of "not less than 100,000 people" for the planned revolt and McMahon's reply of 10 March 1916 confirmed the British agreement to the requests and concluded the ten letters of the correspondence. In April and May, there were discussions initiated by Sykes as to the merits of a meeting to include Picot and the Arabs to mesh the desiderata of both sides. At the same time, logistics in relation to the promised revolt were being dealt with and there was a rising level of impatience for action to be taken by Hussein. Finally, at the end of April, McMahon was advised of the terms of Sykes-Picot and he and Grey agreed that these would not be disclosed to the Arabs.[19]:108–112[22]:57–60

The Arab revolt was officially initiated by Hussein at Mecca on 10 June 1916 although his sons ‘Ali and Faisal had already initiated operations at Medina starting on 5 June.[23] The timing had been brought forward by Hussein and, according to Cairo,[24] "Neither he nor we were at all ready in early June, 1916, and it was only with the greatest of difficulty that a minimum of sufficient assistance in material could be scraped together to ensure initial success."

Colonel Edouard Brémond was dispatched to Arabia in September 1916 as head of the French military mission to the Arabs. According to Cairo, Brémond was intent on containing the revolt so that the Arabs might not in any way threaten French interests in Syria. These concerns were not taken up in London, British-French cooperation was thought paramount and Cairo made aware of that. (Wingate was informed in late November that "it would seem desirable to impress upon your subordinates the need for the most loyal cooperation with the French whom His Majesty’s Government do not suspect of ulterior designs in the Hijaz".)[19]:234–5

As 1916 drew to a close, the Asquith government which had been under increasing pressure and criticism mainly due to its conduct of the war, gave way on 6 December to David Lloyd George who had been critical of the war effort and had succeeded Kitchener as Secretary of State for War after his untimely death in June. Lloyd George had wanted to make the destruction of the Ottoman Empire a major British war aim, and two days after taking office told Robertson that he wanted a major victory, preferably the capture of Jerusalem, to impress British public opinion.[25]:119–120 The EEF were, at the time, in defensive mode at a line on the Eastern edge of the Sinai at El Arish and 15 miles from the borders of Ottoman Palestine. Lloyd George "at once" consulted his War Cabinet about a "further campaign into Palestine when El Arish had been secured". Pressure from Lloyd George (over the reservations of Chief of the General Staff) resulted in the capture of Rafa and the arrival of British forces at the borders of the Ottoman Empire.[25]:47–49

Lloyd George Government (1917 onwards)

Lloyd George set up a new small War Cabinet initially comprising Lords Curzon and Milner, Bonar Law, Arthur Henderson and himself; Hankey became the Secretary with Sykes, Ormsby-Gore and Amery as assistants. Although Balfour replaced Grey as Foreign Secretary, his exclusion from the War Cabinet and the activist stance of its members weakened his influence over foreign policy.[26]

The French chose Picot as French High Commissioner for the soon to be occupied territory of Syria and Palestine. The British appointed Sykes as Chief Political Officer to the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. On 3 April 1917, Sykes met with Lloyd George, Curzon and Hankey to receive his instructions in this regard, namely to keep the French onside while pressing for a British Palestine. First Sykes in early May and then Picot and Sykes together visited the Hejaz later in May to discuss the agreement with Faisal and Hussein.[22]:166 Hussein was persuaded to agree to a formula to the effect that the French would pursue the same policy in Syria as the British in Baghdad; since Hussein believed that Baghdad would be part of the Arab State, that had eventually satisfied him. Later reports from participants expressed doubts about the precise nature of the discussions and the degree to which Hussein had really been informed as to the terms of Sykes–Picot.[19]:165

Italy's participation in the war, governed by the Treaty of London, eventually led to the Agreement of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne in April 1917; at this conference, Lloyd George had raised the question of a British protectorate of Palestine and the idea "had been very coldly received" by the French and the Italians. The War Cabinet, reviewing this conference on 25 April, "inclined to the view that sooner or later the Sykes–Picot Agreement might have to be reconsidered ... No action should be taken at present in this matter".[19]:281

In between the meetings with Hussein, Sykes had informed London that "the sooner French Military Mission is removed from Hedjaz the better" and then Lord Bertie was instructed to request the same from the French on the grounds that the mission was hostile to the Arab cause and which "cannot but prejudice Allied relations and policy in the Hedjaz and may even affect whole future of French relations with the Arabs". After the French response to this, on 31 May 1917, William Ormsby-Gore wrote:

The British Government, in authorising the letters despatched to King Hussein [Sharif of Mecca] before the outbreak of the revolt by Sir Henry McMahon, would seem to raise a doubt as to whether our pledges to King Hussein as head of the Arab nation are consistent with French intentions to make not only Syria but Upper Mesopotamia another Tunis. If our support of King Hussein and the other Arabian leaders of less distinguished origin and prestige means anything it means that we are prepared to recognize the full sovereign independence of the Arabs of Arabia and Syria. It would seem time to acquaint the French Government with our detailed pledges to King Hussein, and to make it clear to the latter whether he or someone else is to be the ruler of Damascus, which is the one possible capital for an Arab State, which could command the obedience of the other Arabian Emirs.[27]

In a further sign of British discontent with Sykes-Picot, in August, Sykes penned a "Memorandum on the Asia Minor Agreement" that was tantamount to advocating its renegotiation else that it be made clear to the French that they "make good – that is to say that if they cannot make a military effort compatible with their policy they should modify their policy". After many discussions, Sykes was directed to conclude with Picot an agreement or supplement to Sykes-Picot ("Projet d'Arrangement") covering the "future status of the Hejaz and Arabia" and this was achieved by the end of September. However, by the end of the year, the agreement had yet to be ratified by the French Government.[19]:422

The Balfour Declaration along with its potential claim in Palestine was in the meantime issued on 2 November and the British entered Jerusalem on December 9, with Allenby on foot 2 days later accompanied by representatives of the French and Italian detachments.

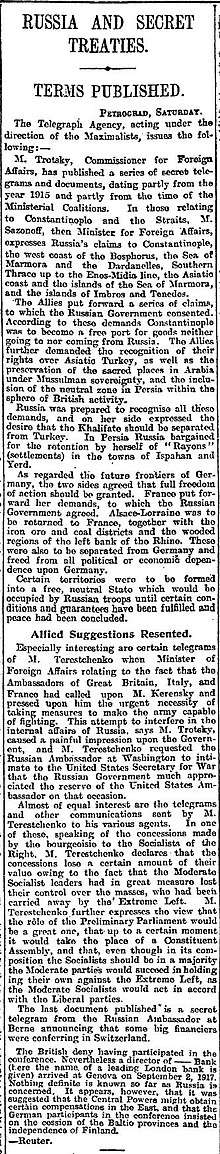

After public disclosure (1917–18)

Russian claims in the Ottoman Empire were denied following the Bolshevik Revolution and the Bolsheviks released a copy of the Sykes–Picot Agreement (as well as other treaties). They revealed full texts in Izvestia and Pravda on 23 November 1917; subsequently, the Manchester Guardian printed the texts on November 26, 1917.[28] This caused great embarrassment between the allies and growing distrust between them and the Arabs. The Zionists had previously confirmed the details of the Agreement with the British government, earlier in April.[19]:207 Wilson had rejected all secret agreements made between the Allies and promoted open diplomacy as well as ideas about self-determination. On 22 November 1917, Leon Trotsky, addressed a note to the ambassadors at Petrograd "containing proposals for a truce and a democratic peace without annexation and without indemnities, based on the principle of the independence of nations, and of their right to determine the nature of their own development themselves". Peace negotiations with the Quadruple Alliance – Germany, Austria–Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey – started at Brest–Litovsk one month later. On behalf of the Quadruple Alliance, Count Czernin, replied on 25 December that the "question of State allegiance of national groups which possess no State independence" should be solved by "every State with its peoples independently in a constitutional manner", and that "the right of minorities forms an essential component part of the constitutional right of peoples to self- determination".

In his turn, Lloyd George delivered a speech on war aims on 5 January, including references to the right of self-determination and "consent of the governed" as well as to secret treaties and the changed circumstances regarding them. Three days later, Wilson weighed in with his Fourteen Points, the twelfth being that "the Turkish portions of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development".

On December 23, 1917, Sykes (who had been sent to France in mid-December to see what was happening with the Projet d'Arrangement) and a representative of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs had delivered public addresses to the Central Syrian Congress in Paris on the non-Turkish elements of the Ottoman Empire, including liberated Jerusalem. Sykes had stated that the accomplished fact of the independence of the Hejaz rendered it almost impossible that an effective and real autonomy should be refused to Syria. However, the minutes also record that the Syrian Arabs in Egypt were not happy with developments and absent a clearer, less ambiguous statement in regard to the future of Syria and Mesopotamia then the Allies as well as the King of the Hedjaz would lose much Arab support.[29]

Sykes was the author of the Hogarth Message a secret January 1918 message to Hussein following his request for an explanation of the Balfour Declaration and the Bassett Letter was a letter (also secret) dated 8 February 1918 from the British Government to Hussein following his request for an explanation of the Sykes–Picot Agreement.

The failure of the Projet d'Arrangement reflected poorly on Sykes and following on from the doubts about his explanations of Sykes-Picot to Hussein the previous year, weakened his credibility on Middle Eastern affairs throughout 1918. Still (at his own request, now Acting Adviser on Arabian and Palestine Affairs at the Foreign Office) he continued his criticism of Sykes-Picot, minuting on 16 February that "the Anglo–French Agreement of 1916 in regard to Asia Minor should come up for reconsideration" and then on 3 March, writing to Clayton, "the stipulations in regard to the red and blue areas can only be regarded as quite contrary to the spirit of every ministerial speech that has been made for the last three months".

On 28 March 1918 the first meeting of the newly formed Eastern Committee was held, chaired by Curzon.[lower-alpha 2]

In May, Clayton told Balfour that Picot had, in response to a suggestion that the agreement was moot, "allowed that considerable revision was required in view of changes that had taken place in the situation since agreement was drawn up", but nevertheless considered that "agreement holds, at any rate principle".

The British issued the Declaration to the Seven on June 16 the first British pronouncement to the Arabs advancing the principle of national self-determination.[30]

On 30 September 1918, supporters of the Arab Revolt in Damascus declared a government loyal to the Sharif of Mecca. He had been declared King of the Arabs by a handful of religious leaders and other notables in Mecca.[31]

The Anglo-French Declaration of November 1918 pledged that Great Britain and France would "assist in the establishment of indigenous Governments and administrations in Syria and Mesopotamia" by "setting up of national governments and administrations deriving their authority from the free exercise of the initiative and choice of the indigenous populations". The French had reluctantly agreed to issue the declaration at the insistence of the British. Minutes of a British War Cabinet meeting reveal that the British had cited the laws of conquest and military occupation to avoid sharing the administration with the French under a civilian regime. The British stressed that the terms of the Anglo–French declaration had superseded the Sykes–Picot Agreement in order to justify fresh negotiations over the allocation of the territories of Syria, Mesopotamia, and Palestine.[32]

George Curzon said the Great Powers were still committed to the Règlement Organique agreement, which concerned governance and non-intervention in the affairs of the Maronite, Orthodox Christian, Druze, and Muslim communities, regarding the Beirut Vilayet of June 1861 and September 1864, and added that the rights granted to France in what is today modern Syria and parts of Turkey under Sykes–Picot were incompatible with that agreement.[33]

At the French embassy in London on Sunday December 1, David Lloyd George and Clemenceau had a private meeting where the latter surrendered French rights to Mosul and to Palestine that had been given by the Sykes–Picot Agreement. There are conflicting views as to whether or not France received anything in exchange. Although Lloyd George and others have suggested that nothing was given in return, according to Rutledge and others, Lloyd George promised at least one or even all of, support for French claims on the Ruhr, that when oil production in Mosul began, France would receive a share and that Sykes–Picot obligation would be maintained as regards Syria.

Paris Peace Conference (1919–20)

The Eastern Committee met nine times in November and December to draft a set of resolutions on British policy for the benefit of the negotiators.[36] On 21 October, the War Cabinet asked Smuts to prepare the peace brief in summary form and he asked Erle Richards to carry out this task resulting in a "P-memo" for use by the Peace Conference delegates.[37][38] The conclusions of the Eastern Committee at page 4 of the P-memo included as objectives the cancellation of Sykes–Picot and supporting the Arabs in their claim to a state with capital at Damascus (in line with the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence).[39]

At the Peace Conference, which officially opened on 18 January, The Big Four (initially, a "Council of Ten" comprising two delegates each from Britain, France, the United States, Italy and Japan) agreed, on 30 January, the outlines of a Mandate system (including three levels of Mandate) later to become Article 22 of the League Covenant. The Big Four would later decide which communities, under what conditions and which Mandatory.

Minutes taken during a meeting of The Big Four held in Paris on March 20, 1919 and attended by Woodrow Wilson, Georges Clemenceau, Vittorio Emanuele Orlando as well as Lloyd George and Lord Balfour,[40] explained the British and French points of view concerning the agreement. It was the first topic brought up during the discussion of Syria and Turkey, and formed the focus of all discussions thereafter.

The Anglo-French Declaration was read into the minutes, Pichon commenting that it showed the disinterested position of both governments in regard to the Arabs and Lloyd George that it was "more important than all the old agreements".[41] Pichon went on to mention a scheme of agreement of 15 February based on the private agreement reached between Clemenceau and Lloyd George the previous December. (According to Lieshout, just before Faisal made his presentation to the conference on the 6th, Clemenceau handed Lloyd George a proposal which appears to cover the same subject matter; Lieshout having accessed related British materials dated the 6th whereas the date in the minutes is unsourced.[19]:340 et seq)

In the subsequent discussions, France staked its claim to Syria (and its mandate) while the British sought to carve out the Arab areas of zones A and B arguing that France had implicitly accepted such an arrangement even though it was the British that had entered into the arrangement with the Arabs.[42]

Wilson intervened and stressed the principle of consent of the governed whether it be Syria or Mesopotamia, that he thought the issues involved the peace of the world and were not necessarily just a matter between France and Britain. He suggested that an Inter-Allied Commission be formed and sent out to find out the wishes of local inhabitants in the region. The discussion concluded with Wilson agreeing to draft a Terms of Reference to the Commission.[43]

On 21 April, Faisal left for the East. Before he left, on 17 April Clemenceau sent a draft letter, in which the French government declared that they recognized "the right of Syria to independence in the form of a federation of autonomous governments in agreement with the traditions and wishes of the populations", and claimed that Faisal had recognized "that France is the Power qualified to render Syria the assistance of various advisors necessary to introduce order and realise the progress demanded by the Syrian populations" and on 20 April, Faisal assured Clemenceau that he had been "Deeply impressed by the disinterested friendliness of your statements to me while I was in Paris, and must thank you for having been the first to suggest the dispatch of the inter-allied Commission, which is to leave shortly for the East to ascertain the wishes of the local peoples as to the future organisation of their country. I am sure that the people of Syria will know how to show you their gratitude."[19]:353

Meanwhile, as of late May, the standoff between the French and the British as to disposition of forces continued, the French continued to press for a replacement of British by French troops in Syria amid arguments about precise geographical limits of same and in general the relationship suffered; after the meeting on the 21st, Lloyd George had written to Clemenceau and cancelled the Long–Bérenger Oil Agreement (a revised version of which had been agreed at the end of April) claiming to have known nothing about it and not wanting it to become an issue while Clemenceau claimed that had not been the subject of any argument.[44][45]

In June 1919, the American King–Crane Commission arrived in Syria to inquire into local public opinion about the future of the country. After many vicissitudes, "mired in confusion and intrigue",[46]"Lloyd George had second thoughts...",[19]:352 the French and British had declined to participate.[47]

The Syrian National Congress had been convened in May 1919 to consider the future of Greater Syria and to present Arab views contained in a July 2 resolution[48] to the King-Crane Commission.

The Peace treaty with Germany was signed on 28 June and with the departure of Wilson and Lloyd George from Paris, the result was that the Turkey/Syria question was effectively placed on hold.[49]

On 15 September, the British handed out an Aide Memoire (which had been discussed privately two days before between Lloyd George and Clemenceau [19]:374 ) whereby the British would withdraw their troops to Palestine and Mesopotamia and hand over Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo to Faisal's forces. While accepting the withdrawal, Clemenceau continued to insist on the Sykes–Picot agreement as being the basis for all discussions.[50]

On 18 September, Faisal arrived in London and the next day and on the 23rd had lengthy meetings with Lloyd George who explained the Aide Memoire and British position. Lloyd George explained that he was "in the position of a man who had inherited two sets of engagements, those to King Hussein and those to the French", Faisal noting that the arrangement "seemed to be based on the 1916 agreement between the British and the French". Clemenceau, replying in respect of the Aide Memoire, refused to move on Syria and said that the matter should be left for the French to handle directly with Faisal.

Faisal arrived Paris on 20 October and eventually on 6 January 1920 Faisal accepted a French mandate "for the whole of Syria", while France in return consented "to the formation of an Arab state that included Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo, and was to be administered by the Emir with the assistance of French advisers" (acknowledged "the right of Syrians to unite to govern themselves as an independent nation".[51]). In the meantime, British forces withdrew from Damascus on 26 November.

Fiasal returned to Damascus on 16 January and Millerand took over from Clemenceau on the 20th. A Syrian National Congress meeting in Damascus declared an independent state of Syria on the 8th of March 1920. The new state intended to include portions of Syria, Palestine, and northern Mesopotamia. Faisal was declared the head of State. At the same time Prince Zeid, Faisal's brother, was declared Regent of Mesopotamia.

In April 1920, the San Remo conference handed out Class A mandates over Syria to France, and Iraq and Palestine to Britain. The same conference ratified an oil agreement reached at a London conference on 12 February, based on a slightly different version of the Long Berenger agreement previously initialled in London on 21 December.

France had decided to govern Syria directly, and took action to enforce the French Mandate of Syria before the terms had been accepted by the Council of the League of Nations. The French issued an ultimatum and intervened militarily at the Battle of Maysalun in June 1920. They deposed the indigenous Arab government, and removed King Faisal from Damascus in August 1920. Great Britain also appointed a High Commissioner and established their own mandatory regime in Palestine, without first obtaining approval from the Council of the League of Nations, or obtaining the formal cession of the territory from the former sovereign, Turkey.

Iraq and the Persian Gulf

In November 1914, the British had occupied Basra. According to the report of the de Bunsen Committee, British interests in Mesopotamia were defined by the need to protect the western flank of India and protect commercial interests including oil. The British also became concerned about the Berlin-Baghdad Railway. Although never ratified, the British had also initialled the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913.

As part of the Mesopotamian Campaign, on 11 March 1917, the British entered Baghdad, the Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October 1918 although the British continued their advance, entering Mosul on the 14 November.

Following the award of the British Mandate of Mesopotamia at San Remo, the British were faced with an Iraqi revolt against the British from July through February 1921 as well as a Kurdish revolt in Northern Iraq. Following the Cairo conference it was decided that Faisal should be installed as ruler in Mandatory Iraq.

The Kurds and Assyrians

As originally cast, Sykes-Picot allocated part of Northern Kurdistan and a substantial part of the Mosul vilayet including the city of Mosul to France in area B, Russia obtained Bitlis and Van in Northern Kurdistan (the contemplated Arab State included Kurds in its Eastern limit split between A and B areas). Bowman says there were around 2.5 million Kurds in Turkey, mainly in the mountain region called Kurdistan.[53]

Sharif Pasha presented a "Memorandum on the Claims of the Kurd People" to the Paris peace Conference in 1919 and the suppressed report of the King–Crane Commission also recommended a form of autonomy in "the natural geographical area which lies between the proposed Armenia on the north and Mesopotamia on the south, with the divide between the Euphrates and the Tigris as the western boundary, and the Persian frontier as the eastern boundary".

The Russians gave up territorial claims following the Bolshevik revolution and at the San Remo conference, the French were awarded the French Mandate of Syria and the English the British Mandate of Mesopotamia. The subsequent Treaty of Sèvres potentially provided for a Kurdish territory subject to a referendum and League of Nations sanction within a year of the treaty. However the Turkish War of Independence led to the treaty being superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne in which there was no provision for a Kurdish State.

The end result was that the Kurds, along with their Assyrian neighbors, were included in the territories of Turkey, Iraq, Syria and Iran.

Conflicting promises and consequences

Many sources contend that Sykes-Picot conflicted with the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence of 1915–1916 and that the publication of the agreement in November 1917 caused the resignation of Sir Henry McMahon.[54] There were several points of difference, the most obvious being Iraq placed in the British red area and less obviously, the idea that British and French advisors would be in control of the area designated as being for an Arab State. Lastly, while the correspondence made no mention of Palestine, Haifa and Acre were to be British and the brown area (a reduced Palestine) internationalised.[55]

Leading up to the centenary of Sykes-Picot in 2016, great interest was generated among the media[56] and academia[57] concerning the long-term effects of the agreement. The agreement is frequently cited as having created "artificial" borders in the Middle East, "without any regard to ethnic or sectarian characteristics, [which] has resulted in endless conflict."[58] The extent to which Sykes-Picot actually shaped the borders of the modern Middle East is disputed.[59][60]

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) claims one of the goals of its insurgency is to reverse the effects of the Sykes–Picot Agreement.[61][62][63] "This is not the first border we will break, we will break other borders," a jihadist from the ISIL warned in a video titled End of Sykes-Picot.[64] ISIL's leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, in a July 2014 speech at the Great Mosque of al-Nuri in Mosul, vowed that "this blessed advance will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes–Picot conspiracy".[65] [66] The Franco-German geographer Christophe Neff wrote that the geopolitical architecture founded by the Sykes–Picot Agreement disappeared in July 2014 and with it the relative protection of religious and ethnic minorities in the Middle East.[67] He claimed furthermore that Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant in some way restructured the geopolitical structure of the Middle East in summer 2014, particularly in Syria and Iraq.[68] Former French Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin presented a similar geopolitical analysis in an editorial contribution for the French newspaper Le Monde.[69]

Notes

- ↑ In 12 January 1916, a memorandum commenting on a draft of the agreement, William Reginald Hall, British Director of Naval Intelligence criticised the proposed agreement on the basis that "the Jews have a strong material, and a very strong political, interest in the future of the country" and that "in the Brown area the question of Zionism, and also of British control of all Palestine railways, in the interest of Egypt, have to be considered".[18]

- ↑ Formed from the merger in March of the Middle East Committee (previously the Mesopotamia Administration Committee) with the Foreign Office Committee on Russia and the interdepartmental Persia Committee.

References

- ↑ Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. New York: Owl. pp. 286, 288. ISBN 0-8050-6884-8.

- ↑ Martin Sicker (2001). The Middle East in the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 26. ISBN 0275968936. Retrieved July 4, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2009-05-08. p. 8.

- ↑ "Syria and Lebanon are often in the news".

- ↑ Castles Made of Sand: A Century of Anglo-American Espionage and Intervention Google Books

- ↑ Middle East still rocking from first world war pacts made 100 years ago Published in The Guardian, December 30, 2015

- ↑ "The war within". The Economist.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Sykes-Picot Agreement - World War I Document Archive". wwi.lib.byu.edu.

- ↑ Peter Mansfield, British Empire magazine, Time-Life Books, no 75, p. 2078

- ↑ Eugene Rogan, The Fall of the Ottomans, p.286

- ↑ Peter Mansfield, The British Empire magazine, no. 75, Time-Life Books, 1973

- ↑ Hawes, Director James (21 October 2003). Lawrence of Arabia: The Battle for the Arab World. PBS Home Video. Interview with Kemal Abu Jaber, former Foreign Minister of Jordan.

- ↑ J. C. Hurewitz (1979). The Middle East and North Africa in World Politics: A Documentary Record. British-French supremacy, 1914-1945. 2. Yale University Press. pp. 16–21. ISBN 978-0-300-02203-2.

- ↑ Huneidi, Sahar; Huneidi, Sarah (7 April 2001). "A Broken Trust: Sir Herbert Samuel, Zionism and the Palestinians". I.B.Tauris – via Google Books.

- ↑ Rose, N.A. (2013). The Gentile Zionists: A Study in Anglo-Zionist Diplomacy 1929-1939. Routledge. p. 264. ISBN 9781135158651.

- ↑ Hurewitz, J.C. (June 1979). The Middle East and North Africa in World Politics:A Documentary Record. British-French supremacy, 1914-1945 Vol.2. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300022032.

- ↑ A Line in the Sand, James Barr,Simon and Schuster,2011 Ch.2

- ↑ Friedman 1992, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Britain and the Arab Middle East: World War I and its Aftermath, Robert H. Lieshout, I.B.Tauris, 2016

- ↑ Desplatt, Juliette (May 16, 2016). "Dividing the bear's skin while the bear is still alive". The national Archives. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ↑ "The Sykes-Picot Agreement : 1916". Yale Law School The Avalon Project. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- 1 2 Isaiah Friedman, Palestine, a Twice-promised Land?: The British, the Arabs & Zionism, 1915–1920 (Transaction Publishers 2000), ISBN 1-56000-391-X

- ↑ The Arab Movements in World War I, Eliezer Tauber, Routledge, 2014 ISBN 9781135199784 pp. 80–81

- ↑ Arab Bulletin No 52, 31 May 1917, Hejaz, A Year of Revolt, p.249

- 1 2 Woodfin, E. (2012). Camp and Combat on the Sinai and Palestine Front: The Experience of the British Empire Soldier, 1916-18. Springer. ISBN 1137264802.

- ↑ '"The erosion of Foreign Office influence in the making of foreign policy, 1916–1918", Roberta M.Warman, The Historical Journal, CUP, Vol. 15, No. 1, Mar. 1972, pp. 133–159

- ↑ UK National Archives CAB/24/143, Eastern Report, No. XVIII, May 31, 1917

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2009-05-08. p. 9.

- ↑ Foreign Relations of the United States, 1918. Supplement 1, The World War Volume I, Part I: The continuation and conclusion of the war—participation of the United States, p. 243

- ↑ Paris, Timothy J. (2003). Britain, the Hashemites, and Arab Rule, 1920-1925: the Sherifian solution. London: Frank Cass. p. 50. ISBN 0-7146-5451-5.

- ↑ Jordan: Living in the Crossfire, Alan George, Zed Books, 2005, ISBN 1-84277-471-9, page 6

- ↑ See Allenby and General Strategy in the Middle East, 1917–1919, By Matthew Hughes, Taylor and Francis, 1999, ISBN 0-7146-4473-0, 113–118

- ↑ CAB 27/24, E.C. 41 War Cabinet Eastern Committee Minutes, December 5, 1918

- ↑ A Line in the Sand. James Barr, Simon and Schuster, 2011, Ch. 1

- ↑ "Peace conference: memoranda respecting Syria, Arabia and Palestine". The British Library.

- ↑ Goldstein, Erik (1987). "British Peace Aims and the Eastern Question: The Political Intelligence Department and the Eastern Committee, 1918". Middle Eastern Studies. 23 (4): 423. JSTOR 4283203.

- ↑ Dockrill; Steiner (2010). "The Foreign Office at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919". The International History Review. 2 (1): 58. doi:10.1080/07075332.1980.9640205.

- ↑ Prott, Volker (2016). The Politics of Self-Determination:Remaking Territories and National Identities in Europe, 1917–1923. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780191083549.

- ↑ "Peace conference: memoranda respecting Syria, Arabia and Palestine, P.50, Syria". British Library. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ↑ The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919, p. 1

- ↑ The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919, p. 3

- ↑ "FRUS: Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919". digicoll.library.wisc.edu.

- ↑ "FRUS: Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919". digicoll.library.wisc.edu.

- ↑ "FRUS: Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919". digicoll.library.wisc.edu.

- ↑ "FRUS: Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919". digicoll.library.wisc.edu.

- ↑ Allawi, Ali A. (11 March 2014), Faisal I of Iraq, Yale University Press, p. 213, ISBN 978-0-300-12732-4

- ↑ "FRUS: Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: The Council of Four: minutes of meetings May 24 to June 28, 1919". digicoll.library.wisc.edu.

- ↑ "Resolutions of the General Syrian Congress". Documenting Modern World History. July 2, 1919. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

... resolved to submit the following as defining the aspirations of the people who have chosen us to place them before the American section of the Inter-Allied Commission.

- ↑ "FRUS: Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: The Council of Heads of Delegations: minutes of meetings July 1 to August 28, 1919". digicoll.library.wisc.edu.

- ↑ "Notes of a Meeting of the Heads of Delegations of the Five Great Powers, Paris, 15 September, 1919". Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ Britain, the Hashemites and Arab Rule, 1920–1925, by Timothy J. Paris, Routledge, 2003, ISBN 0-7146-5451-5, page 69

- ↑ Bowman, Isaiah (1921). The New World: Problems in Political Geography. New York: World Book Company. p. 445.

- ↑ Bowman, Isaiah (1921). The New World: Problems in Political Geography. New York: World Book Company. p. 445.

- ↑ See CAB 24/271, Cabinet Paper 203(37)

- ↑ Yapp, Malcolm (1987). The Making of the Modern Near East 1792–1923. Harlow, England: Longman. p. 281–2. ISBN 978-0-582-49380-3.

- ↑ Such coverage includes Osman, T. (2013) "Why border lines drawn with a ruler in WW1 still rock the Middle East"; Wright, R. (2016) "How the curse of Sykes-Picot still haunts the Middle East"; and Anderson, S. (2016) "Fractured lands: How the Arab world came apart"

- ↑ See, for example, academic conferences hosted by York St. John University, the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, and symposium by the American Society of International Law.

- ↑ Ibrahim, S.E. "Islam and prospects for democracy in the Middle East" (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2010. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ↑ Bali, A. "Sykes-Picot and "Artificial" States". American Journal of International Law. 110 (3).

- ↑ Pursley, Sara (June 2, 2015). "'Lines Drawn on an Empty Map': Iraq's Borders and the Legend of the Artificial State". Jadaliyya. Arab Studies Institute.

- ↑ "This is not the first border we will break, we will break other borders," a jihadist from ..." www.theguardian.com. The Guardian. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ "Watch this English-speaking ISIS fighter explain how a 98-year-old colonial map created today's conflict". LA Daily News. 7 February 2014. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- ↑ Phillips, David L. "Extremists in Iraq need a history lesson". CNBC.

- ↑ Tran, Mark and Weaver, Matthew (30 June 2014). "Isis announces Islamic caliphate in area straddling Iraq and Syria". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ Wright, Robin (April 30, 2016). "How the Curse of Sykes-Picot Still Haunts the Middle East". The New Yorker.

- ↑ "First Appearance of ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi". YouTube.com. 17 November 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ "Bientôt le souvenir de l'église catholique chaldéenne et des églises syriaques (orthodoxes & catholiques) sera plus qu'un souffle de vent chaud dans le désert". paysages (in French). Le Monde. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Yazidis d'Irak – le cri d'angoisse d'une députée du parlement irakien". paysages (in French). Le Monde. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ↑ Dominique de Villepin. "Ne laissons pas le Moyen-Orient à la barbarie !" (in French). Le Monde. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

See also

- Balfour Declaration, November 1917; the British government announces support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine

- Durrand line, separates Afghanistan and Pakistan

- San Remo conference, with a resolution adopted on 25 April 1920; the basis for the British Mandate for Palestine

- British Mandate for Palestine (legal instrument), confirmed by the League of Nations on 24 July 1922

- UN Resolution 181 adopted 29 November 1947, recommending the partition of Palestine

Further reading

- Anghie, Antony T. "Introduction to Symposium on the Many Lives and Legacies of Sykes-Picot." American Journal of International Law 110 (2016): 105–108.

- Dodge, Toby. "The Danger of Analogical Myths: Explaining the Power and Consequences of the Sykes-Picot Delusion." American Journal of International Law 110 (2016): 132–136.

- Donaldson, Megan. "Textual Settlements: The Sykes–Picot Agreement and Secret Treaty-Making." American Journal of International Law 110 (2016): 127–131.

- James Barr (2012). A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the Struggle That Shaped the Middle East. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 1-84739-457-4.

- Fitzgerald, Edward Peter. "France's Middle Eastern ambitions, the Sykes-Picot negotiations, and the oil fields of Mosul, 1915–1918." Journal of Modern History 66.4 (1994): 697–725.

- Friedman, Isaiah (1992). The Question of Palestine. Transaction Publishers. pp. 97–118. ISBN 0-88738-214-2.

- Gil‐Har, Yitzhak. "Boundaries delimitation: Palestine and Trans‐Jordan." Middle Eastern Studies 36.1 (2000): 68-81. excerpt

- Kedourie, Elie. England and the Middle East: the destruction of the Ottoman Empire, 1914–1921 (1978).

- Kitching, Paula. "The Sykes-Picot agreement and lines in the sand." Historian 128 (2015): 18-22.

- Ottaway, Marina. "Learning from Sykes-Picot." (WWIC Middle East Program Occasional Paper Series, 2015). online

- Erik Jan Zürcher (2004). Turkey: A Modern History. I.B.Tauris. pp. 143–145. ISBN 1-86064-958-0.

- David Fromkin (1991). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. Publisher:Don't know yet. ISBN 0805088091.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sykes–Picot Agreement. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |