Tachara

| Tachara | |

|---|---|

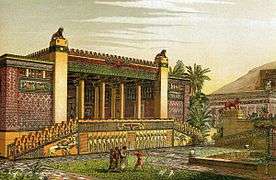

Ruins of the Tachara, Persepolis. | |

| General information | |

| Status | in ruins |

| Architectural style | Achaemenid architecture |

| Location |

Persepolis Marvdasht, Fars Province |

| Country |

|

| Coordinates | 29°56′04″N 52°53′22″E / 29.9344°N 52.88955°E |

| Technical details | |

| Material | stone |

| Website | |

| UNESCO: Persepolis | |

The Tachara, or the Tachar Château, also referred to as the Palace of Darius the Great,[1] was the exclusive building of Darius I at Persepolis, Iran. It is located 70 km northeast of the modern city of Shiraz in Fars Province.

History and construction

The construction dates back to the time of the Achaemenid Empire (550 BC–330 BC). The building has been attributed to Darius I,[2][3] but only a small portion of it was finished under his rule. It was completed after the death of Darius I in 486, by his son and successor, Xerxes I,[4] who called it a taçara in Old Persian, translated to "winter palace". It was then used by Artaxerxes I. Its ruins are immediately south of the Apadana.

In the 4th century BC, following his invasion of Achaemenid Persia in 330 BC, Alexander the Great allowed his troops to loot Persepolis. This palace was one of the few structures that escaped destruction in the burning of the complex by Alexander the Great's army.

Structure

The Tachara stands back to back to the Apadana, and is oriented southward.[5] Measuring 1,160 square meters (12,500 square feet), it is the smallest of the palace buildings on the Terrace at Persepolis.

As the oldest of the palace structures on the Terrace,[2] it was constructed of the finest quality gray stone. The surface was almost completely black and polished to a glossy brilliance. This surface treatment combined with the high quality stone is the reason for it being the most intact of all ruins at Persepolis today. Although its mud block walls have completely disintegrated, the enormous stone blocks of the door and window frames have survived.

Its main room is a mere 15.15 m × 15.42 m (49.7 ft × 50.6 ft) with three rows of four columns. A complete window measuring 2.65 m × 2.65 m × 1.70 m (8.7 ft × 8.7 ft × 5.6 ft) was carved from a single block of stone and weighed 18 tons. The door frame was fashioned from three separate monoliths and weighed 75 tons.

Like many other parts of Persepolis, the Tachara has reliefs of tribute-bearing dignitaries. There are sculptured figures of lance-bearers carrying large rectangular wicker shields, attendants or servants with towel and perfume bottles, and a royal hero killing lions and monsters. There is also a bas-relief at the main doorway depicting Darius I wearing a crenellated crown covered with sheets of gold.[2]

The Tachara is connected to the south court by a double reversed stairway. Later under the reign of Artaxerxes III, a new stairway was added to the northwest of the Tachara which is connected to the main hall through a new doorway. On walls of these stairways, there are sculptured representations of figures such as servants, attendants and soldiers dressed in Median and Persian costumes, as well as gift-bearing delegations flanking carved inscriptions.[2]

Darius the Great's pride at the superb craftsmanship is evident by his ordering the following inscription on all 18 niches and window frames: Frames of stone, made for the Palace of King Darius.

Function

The function of the building, however, was more ceremonial than residential. Upon completion, it served in conjunction with the earlier south oriented entrance stairs as the Nowruz venue until the other buildings that would comprise Persepolis could be finished, which included a provisional union of the Apadana, the Throne Hall and a Banquet Hall.

See also

References

- ↑ Merrill F. Unger (Jun 1, 2009). "Architecture: Persian". The New Unger's Bible Dictionary.

- 1 2 3 4 Encyclopædia Iranica. "The Palace of Darius (the Tačara)". PERSEPOLIS.

- ↑ John Curtis, St John Simpson (Mar 30, 2010). The World of Achaemenid Persia: History, Art and Society in Iran and the Ancient Near East. p. 233.

- ↑ Penelope Hobhouse (2004). The Gardens of Persia. p. 52.

- ↑ Ali Mousavi (Apr 19, 2012). Persepolis: Discovery and Afterlife of a World Wonder. p. 21.