Kigali

| Kigali | |

|---|---|

|

Kigali, Rwanda | |

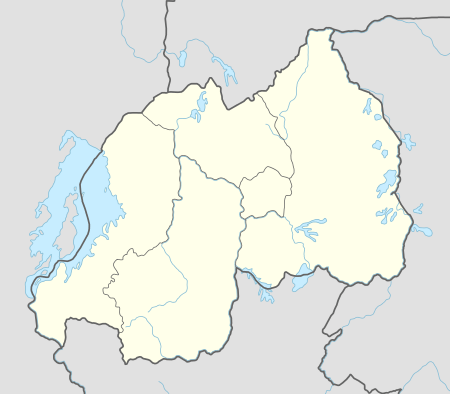

Kigali Map of Rwanda showing the location of Kigali. | |

| Coordinates: 1°56′38″S 30°3′34″E / 1.94389°S 30.05944°ECoordinates: 1°56′38″S 30°3′34″E / 1.94389°S 30.05944°E | |

| Country | Rwanda |

| Province | Kigali Province |

| Founded | 1907 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Marie-Chantal Rwakazina |

| Area | |

| • Total | 730 km2 (280 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,567 m (5,141 ft) |

| Population (2012 census) | |

| • Total | 1,132,686 |

| • Density | 1,600/km2 (4,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (none) |

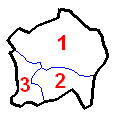

| Districts 1. Gasabo 2. Kicukiro 3. Nyarugenge |

|

| Website |

www |

Kigali (Kinyarwanda: [Kiɡɑɾí]) is the capital and largest city of Rwanda. It is near the nation's geographic centre. The city has been Rwanda's economic, cultural, and transport hub since it became capital at independence in 1962. The city hosts the main residence and offices of the President of Rwanda and government ministries. The city is within the province of Kigali City, which was enlarged in January 2006, as part of local government reorganisation in the country. Kigali's city limits cover the whole province; it is consolidated. The city's urban area covers about 70% of the municipal boundaries.[1]

History

The earliest inhabitants of what is now Rwanda were the Twa, a group of aboriginal pygmy hunter-gatherers who settled the area between 8000 and 3000 BC and remain in the country today.[2][3] They were followed between 700 BC and 1500 AD by a number of Bantu groups, including the Hutu and Tutsi, who began clearing forests for agriculture.[4][3] According to oral history the Kingdom of Rwanda was founded in the 14th century on the shores of Lake Muhazi, around 40 kilometres (25 mi) east of modern Kigali.[5][6][7][8] At that time Rwanda was a small state in a loose confederation with larger and more powerful neighbours, Bugesera and Gisaka.[9] By playing these neighbours against each other, the early kingdom flourished in the area, expanding westwards towards Lake Kivu and taking the Kigali area in the process.[10][11] In the late 16th or early 17th centuries, the kingdom of Rwanda was invaded by the Banyoro and the kings forced to flee westward, leaving Kigali and eastern Rwanda in the hands of Bugesera and Gisaka.[6][12] The formation in the 17th century of a new Rwandan dynasty by mwami Ruganzu Ndori, followed by eastward invasions and the conquest of Bugesera, marked the beginning of the Rwandan kingdom's dominance in the area.[13] The capital of the kingdom was at Nyanza, in the south of the country.[14]

The city of Kigali was founded in 1907 by German administrator and explorer Richard Kandt.[15] Rwanda and neighbouring Burundi had been assigned to Germany by the Berlin Conference of 1884,[16] and Germany established a presence in the country in 1897 with the formation of an alliance with the king, Yuhi V Musinga.[17] Kandt arrived in 1899, exploring Lake Kivu and searching for the source of the Nile.[18] When Germany decided in 1907 to separate the administration of Rwanda from that of Burundi, Kandt was appointed as the country's first resident.[19] He chose to make his headquarters in Kigali due to its central location in the country,[20] and also because the area afforded good views and security. Kandt built himself a house in Nyarugenge, the first European-style house in the city, which remains in use today as the Kandt House Museum of Natural History.[21] Despite a German ordinance written in 1905, which prohibited "non-indigenous natives" from entering Rwanda,[22] Kandt began permitting the entry of Indian traders in 1908 allowed commercial activity to begin in Rwanda in 1908.Kigali has many population than other provinces in the country (Emmanuel Kagiraneza). [15][22] The first businesses were established in Kigali that year by Greek and Indian merchants,[15] with assistance from Baganda and Swahili people.[23] Items traded included cloth and beads.[23] However, commercial activity was limited and there were only around 30 firms in the city by 1914.[24] Kandt also opened government-run schools in Kigali, which began educating Tutsi students.[25]

Belgian forces took control of Rwanda and Burundi in 1916, during World War I, and were granted sovereignty by a League of Nations mandate in 1919.[26]. In early 1917, Belgium attempted to assert direct rule on the colony, placing King Musinga under arrest and sidelining Rwandans in the judiciary.[27] In this period, Kigali was one of two provincial capitals, alongside Gisenyi.[28] The difficulty of governing the complex Rwandan society, and a crippling famine, led the Belgians to re-establish the German-style indirect rule at the end of 1917.[29] Musinga was restored to his throne at Nyanza, with Kigali remaining home to the colonial administration.[30][31] This arrangement persisted until the mid-1920s,[32] but from 1924 the Belgians began once more to sideline the monarchy, this time permanently.[33] Belgium took over control of dispute resolution, appointment of officials and expansion of control.[32] Kigali remained relatively small through the remainder of the colonial era, as much of the administration took place in Ruanda-Urundi's capital Usumbura, now known as Bujumbura in Burundi.[34] Usumbura's population exceeded 50,000 during the 1950s, and was the colony's only European-style city,[34] while Kigali's population remained at around 6,000 until independence in 1962.[35]

Kigali become the capital upon Rwandan independence in 1962[36]. The traditional capital was the seat of the mwami (Kings Yuhi V, Mutara III and Kigeli IV) in Nyanza, while the colonial seat of power was in Butare, then known as Astrida. Butare was initially the leading contender to be the capital of the new independent nation, but Kigali was chosen because of its more central location. The city grew slowly during the following decades, but retained a small-town feel, with just 25,000 people and five paved roads by the early 1970s.[37] On 6 July 1973 there was a bloodless military coup, in which minister of defence Juvénal Habyarimana overthrew ruling president Gregoire Kayibanda.[37] Businesses closed for a few days, and troops patrolled across the city,[38] but life had returned to normal and the army had left the streets by 11 July.[39]

In April 1994 President Habyarimana was assissinated, when his plane was shot down near Kigali Airport.[40] This was the catalyst for the Rwandan genocide, in which 500,000–1,000,000[41] Tutsi and politically moderate Hutu were killed in well-planned attacks on the orders of the interim government.[42] Opposition politicians based in Kigali were killed on the first day of the genocide,[43] and the city then became the setting for fierce fighting between the army (mostly Hutu) and the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). On 8 April, Rwandan government forces attacked the RPF base in the parliament building from several directions, but RPF troops successfully fought back.[44] The RPF then began an attack from the north on three fronts, seeking to link up quickly with its isolated troops in Kigali.[45] The RPF advanced steadily, capturing large areas of the countryside to the north and east of Kigali,[46] but avoiding an attack on the city itself, because the city was too heavily defended.[47] They instead conducted manoeuvres designed to encircle Kigali and cut off supply routes,[48], as well as capturing the rest of the country.[49] By mid-June, the RPF encirclement was complete, and they began fighting for the city itself.[50] The government forces had superior manpower and weapons but the RPF fought tactically,[50] and were able to exploit the fact that the government forces were concentrating on the genocide rather than the fight for Kigali.[50] The RPF took control of Kigali on 4 July,[51] a date now commemorated as the Liberation Day national holiday.[52]

Although damaged, the city's structure has recovered.

Geography

Kigali is located in the centre of Rwanda, at 1°57′S 30°4′E / 1.950°S 30.067°E.[53] The city is coterminous with the province of Kigali, one of the five provinces of Rwanda introduced in 2006 as part of a restructuring of local government in the country.[54] The city has boundaries with the Northern, Eastern and Southern provinces.[54] The city is divided into three administrative districts—Nyarugenge, which lies in the south west, Kicukiro in the south east, and Gasabo, which occupies the northern half of the city's territory.[55] Kigali lies in a region of rolling hills,[6] with a series of valleys and ridges joined by steep slopes.[56] Kigali lies between the two mountains of Mount Kigali and Mount Jali,[20] both of which have altitudes over 1,800 m (5,906 ft),[57] while the lowest areas of the city have an altitude of 1,800 m (5,906 ft).[58] Geologically, the city lies in a granitic and metasedimentary region, with lateritic soils on the hills and alluvial soils in the valleys.[59]

The Nyabarongo River, part of the upper headwaters of the Nile,[60] forms the western and southern borders of the administrative city of Kigali,[61] although this river lies somewhat outside the built-up urban area.[62] The largest river running through the city is the Nyabugogo River, which flows south from Lake Muhazi before flowing west between Mount Kigali and Mount Jali, and draining into the Nyabarongo.[63] The Nyabugogo is fed by various smaller streams throughout the city, and its drainage basin contains most of Kigali's territory,[63] other than areas in the south which outflow directly to the Nyabarongo.[64] The rivers are flanked by wetlands, which act as a water store and flood protection for the city, although these are under threat from agriculture and development.[64]

Cityscape

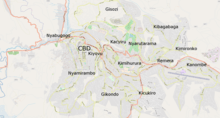

The central business district (CBD) (known in Kinyarwanda as mu mujyi) of Kigali lies on Nyarugenge Hill, and was the site of the original city founded by Richard Kandt in 1907.[20] The house that Kandt lived in is now a museum.[65] Geographically, the CBD lies towards the western edge of the built-up area,[20] as the terrain to the east was more suitable for development of the expanding city than the high slopes of Mount Kigali to the west. Several of Rwanda's highest buildings, including the 20-storey Kigali City Tower, are located in the CBD, as are the headquarters of the country's largest banks and businesses.[66] Other buildings in the CBD include the upmarket Serena, Marriott and Mille Collines hotels,[67] the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali,[68] the national university's College of Science and Technology,[69] and government buildings such as the National Bank of Rwanda[70] and the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning.[71]

To the south west of the CBD, and also on the Nyarugenge Hill, is the suburb of Nyamirambo.[72] This was the second part of the city to be settled, being built in the 1920s by the Belgian colonial government as a home for civil servants and Swahili traders.[73] This latter group were mostly members of the Islamic faith, which led to Nyamirambo being known as the "Muslim Quarter".[73] Nyamirambo's Green Mosque (Masjid al-Fatah) is the oldest mosque in Kigali, dating back to the 1930s.[74] Travel publisher Rough Guides has described Nyamirambo as "Kigali's coolest neighbourhood", citing its multi-cultural status and an active nightlife, which is not found in much of the rest of the city.[74] North of Nyamirambo, and west of the CBD is Nyabugogo. Situated at the lowest part of the city, in the valley of the eponymous Nyabugogo River, Nyabugogo is home to Kigali's principal bus and share taxi station, with vehicles departing for numerous domestic and international destinations.[75]

The remainder of Kigali's suburbs lie to the east of the CBD, with an urban sprawl spanning the many hills and ridges. Kiyovu is the closest, on the eastern slopes of Nyarugenge Hill. The higher part of Kiyovu, to the south of main road KN3, has been home to wealthy expats and Rwandans since colonial times, with large houses and high-end restaurants.[76] The lower part of Kiyovu, north of the main road, consisted until 2008 of informal settlements that had formed after independence, when strict residence rules were relaxed.[76] The houses in lower Kiyovu were expropriated by the government in 2008 with residents compensated or relocated to other areas, including to a purpose-built estate in the Batsinda neighbourhood.[77] The government has plans to create a new business district in lower Kiyovu to complement the existing CBD, although as of late 2017 there had been only a handful of buildings erected there.[77] Other eastern suburbs include Kacyiru, home to most government departments and the office of the president;[78] Gisozi, where the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre is located;[79] Nyarutarama, an upmarket suburb housing the city's only golf course;[80] Kimihurura; Remera and Kanombe, 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from the CBD on the eastern edge of the city, where Kigali International Airport is located.[81]

Climate

Like the rest of Rwanda, Kigali has a temperate tropical highland climate, with lower temperatures than are typical for equatorial countries because of its high elevation.[82] Under the Köppen climate classification, Kigali straddles the subtropical highland climate and tropical savanna climate zones. The city has a typical daily temperature range between 12 and 27 °C (54 and 81 °F), with little variation through the year.[83] There are two rainy seasons in the year; the first runs from February to June and the second from September to December. These are separated by two dry seasons: the major one from June to September, during which there is often no rain at all, and a shorter and less severe one from December to February.[84] The wettest month is April, with an average rainfall of 154 millimetres (6.1 in), while the driest month is July.[83] Global warming has caused a change in the pattern of the rainy seasons. According to a report by the Strategic Foresight Group, change in climate has reduced the number of rainy days experienced during a year, but has also caused an increase in frequency of torrential rains.[85] Strategic Foresight also characterise Rwanda as a fast warming country, with an increase in average temperature of between 0.7 °C to 0.9 °C over fifty years.[85]

| Climate data for Kigali, Rwanda | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.4 (79.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.2 (81) |

26.1 (79) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

16.1 (61) |

16.2 (61.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

15.0 (59) |

16.0 (60.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 76.9 (3.028) |

91.0 (3.583) |

114.2 (4.496) |

154.2 (6.071) |

88.1 (3.469) |

18.6 (0.732) |

11.4 (0.449) |

31.1 (1.224) |

69.6 (2.74) |

105.7 (4.161) |

112.7 (4.437) |

77.4 (3.047) |

950.9 (37.437) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 11 | 11 | 15 | 18 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 17 | 17 | 14 | 133 |

| Source: [83] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

As of the 2012 Rwandan census, the population of Kigali was 1,132,686,[86] with an urban population of 859,332.[86] At the time of independence in 1962, Kigali had a population of 6,000, consisting primarily of those associated with the Belgian colonial residency.[87] The population grew considerably after it was named as the independent nation's capital,[88] although it remained a relatively small city until the 1970s due to government policies restricting rural-to-urban migration.[89] The population reached 115,000 by 1978, and 235,000 by 1991.[90] The city lost a large fraction of its population during the 1994 genocide,[91] including those killed and those who fled to neighbouring countries.[92] From 1995, however, the economy began to recover and large numbers of long-term Tutsi refugees returned from Uganda.[93] Many of these refugees settled in Kigali and other urban areas, due to difficulty in obtaining land in other parts of the country.[94] This phenomenon, coupled with a high birth rate[95] and increased rural-to-urban migration, meant that Kigali reattained its previous population quite quickly and began to grow even more rapidly than before.[96] The population exceeded 600,000 in 2002, and in the 2012 census had reached 1.13 million, with the boundaries of the city expanded.[88]

As of the 2012 census, 51.7 percent of residents were male[97] and 48.3 percent were female.[98] The Rwanda Environment Management Authority hypothesised that the high male-to-female ratio was due to a tendency for men to migrate to the city in search of work outside the agricultural sector, while their wives remained in a rural home.[99] The population is young, with 73 percent of residents being less than 30 years old,[99] and 94 percent under the age of 50.[100] In 2014, the proportion of people classified as living in poverty within Kigali was 15 percent, compared with 37 percent for Rwanda as a whole.[101] The 2012 census recorded a workforce of 487,000 in Kigali.[102] The city's biggest employment sector is agriculture, fishing and forestry, covering 24 percent of the workforce; utilities and financial services with 21 percent; trade 20 percent and government 12 percent.[102]

Economy

Mines for tin ore (cassiterite) have operated nearby, and the city built a smelting plant in the 1980s. Business in Rwanda has been growing in the 21st century, and many new buildings have arisen across the city, including the BCDI Tower, Centenary House, Kigali City Tower and Kigali Convention Centre. Tourism provides important input into the economy.[103]

Government

Kigali is a province-level city governed by a city council who appoints an executive committee to run the day-to-day operations of the city. The executive committee consists of a mayor and two deputies. The city is split into three administrative districts: Gasabo, Kicukiro, and Nyarugenge.[104] It contained parts of the former province of Kigali Rural.

List of mayors

- Francois Karera, 1975-1990[105]

- Tharcisse Renzaho, 1990-1994

- Rose Kabuye, 1994-1997

- Protais Musoni, 1997-1999

- Marc Kabandana, 1999-2001

- Theoneste Mutsindashyaka, 2001-2006

- Aisa Kirabo Kacyira, 2006-2011

- Fidèle Ndayisaba, 2011-2016 [106]

- Monique Mukaruliza, 2016[107][108]

- Pascal Nyamulinda, 2017– May 2018[109]

- Chantal Rwakazina May 2018 - present[110]

Education

Colleges and universities

The administrative head office of the University of Rwanda (UR) is in Kigali.[111] The UR College of Science and Technology campus is in the Southern part of Kigali, at Avenue de l'Armee. (The main academic campus of University of Rwanda is in Butare, the former National University of Rwanda.) Carnegie Mellon University's The College of Engineering has an international campus located in Kigali known as Carnegie Mellon University Africa.[112]

Other renowned universities also have their headquarters or campuses in Kigali including: Kigali Independent University and Mount Kenya University.[113]

Primary and secondary schools

Lycée de Kigali is the second-largest secondary school in Rwanda, after the Groupe Scolaire in Butare.

Green Hills Academy, in the upscale suburb of Nyarutarama, is a top private school, offering IB at A level, and the Cambridge International Program at O level. It is a PASCH partner school offering German. It has a 50/50 English-French curriculum as well. École Antoine de Saint-Exupéry de Kigali, the French school, is in Kigali. École Belge de Kigali, the Belgian school, is in Kigali. International School of Kigali is also in Kigali. The Earth School -the International Montessori School of Rwanda- is a private preschool and elementary program serving children ages 2–12.

Sports

The city is a stronghold for basketball as traditionally, roughly half of the teams of Rwanda's National Basketball League are based there, including 2016 Champion Patriots BBC, record holding Champion Espoir BBC and others, including APR basketball club, IPRC-Kigali and Cercle Sportif de Kigali (CSK).

Transportation

The city has an international airport, Kigali International Airport, with passenger flights to (among others) Amsterdam, Brussels, Nairobi, Entebbe, Johannesburg, and Istanbul. The airport is somewhat limited by its location on the top of a hill, and a brand new one is currently being built in the Nyamata area, some 40 km (25 mi) from Kigali.

There are several daily coach services which depart from Kigali to destinations in East Africa. Most leave from the Nyabugogo bus station. These services include:

- Modern Coast, a Kenyan coach and courier service which connects Gisenyi/Goma through Kyanika and Kigali through Gatuna to Kampala and Nairobi. It offers online booking and payment, three seat classes and in some busses personal TVs and 240 V/USB sockets.

- Jaguar Executive Coaches, which connects Kigali to Kampala, the Ugandan capital, via Gatuna or via Kayonza and Kagitumba.

- Akamba Bus Services, which runs services to Kampala (8 hours), Nairobi in Kenya (24 hours), Dar es Salaam in Tanzania (36 hours) and Mombasa in Kenya (32 hrs)

- Yahoo Car Express - A minibus service running between Kigali and Bujumbura in Burundi.

- Kampala Coach Ltd, which runs services to Kampala (8 hours), Nairobi in Kenya (24 hours), Dar es Salaam in Tanzania (36 hours) and Mombasa in Kenya (32 hours).

Kigali is the hub of the Rwanda transport network, with 15 minutes express bus routes to all major towns in the country. There are also taxi minibus services (matatus) leaving from Kigali, which also go through to the major towns, but some of them stop frequently along the route to pick people up or drop them off.

Public transport within Kigali is shifting from using small matatus to bigger city buses, which are connecting the most important sectors. These buses use a cash-free payment system called Tap&Go[114]. In 2017, matatus were still used to connect the more remote areas of the city. In contrast to the national express buses, these services wait to fill up before setting off from the terminus, then pick up and drop off frequently en route.

Kigali has many taxis (known as 'special hire' or 'taxi voiture'), which are generally painted white with an orange stripe down the side. Even more popular are motorbike taxis ('taxi moto'), which offer a service similar to a taxi, but for lower prices, typically in the range 300-1000 FRW.

Future

Under a master plan for 2040, Kigali will be decentralised, with business, shopping, and leisure districts, and suburbs. The plan calls for skyscrapers, arching pedestrian walkways and green spaces to be built, alongside amenities such as fountains and a wetlands conservation area. In addition, there will be an effective public transportation network. However, among the most pressing problems is affordable housing for the majority of the city's population, and a number of schemes are under consideration. The city's population of about 1.2 million is expected to triple by that time.[115]

Notes

- ↑ "Kigali at a Glance" Archived 2014-02-28 at the Wayback Machine., Official Website of Kigali City, accessed 15 August 2008

- ↑ Chrétien 2003, p. 44.

- 1 2 Mamdani 2002, p. 61.

- ↑ Chrétien 2003, p. 58.

- ↑ Dorsey 1994, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 Munyakazi & Ntagaramba 2005, p. 18.

- ↑ Prunier 1999, p. 18.

- ↑ Rwanda Development Board.

- ↑ Chrétien p158

- ↑ Dorsey 1994, p. 38.

- ↑ Appiah & Gates 2010, p. 651.

- ↑ Chrétien 2003, p. 158.

- ↑ Dorsey 1994, p. 39.

- ↑ Twagilimana 2015, p. 175.

- 1 2 3 Dorsey 1994, p. 46.

- ↑ Appiah & Gates 2010, p. 218.

- ↑ Carney 2013, p. 24.

- ↑ http://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/111005/

- ↑ Louis 1963, p. 146.

- 1 2 3 4 Tumwebaze (I) 2011.

- ↑ "Institute of National Museums of Rwanda". Archived from the original on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- 1 2 Louis 1963, p. 168.

- 1 2 Linden & Linden 1977, p. 103.

- ↑ Louis 1963, p. 172.

- ↑ Linden & Linden 1977, p. 110.

- ↑ Prunier 1999, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Linden & Linden 1977, p. 127.

- ↑ Des Forges 2011, p. 135.

- ↑ Linden & Linden 1977, p. 130.

- ↑ Des Forges 2011, p. 142.

- ↑ Dorsey 1994, p. 275.

- 1 2 Des Forges 2011, p. 210.

- ↑ Geary 2003, p. 96.

- 1 2 Infor Congo 1958.

- ↑ Ntagungura 2011.

- ↑ MURAMILA, GASHEEGU. "100 mayors for City centenary celebrations". The New Times Rwanda. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- 1 2 Mohr 1973.

- ↑ Associated Press 1973.

- ↑ U.S. Department of State 1973.

- ↑ BBC News (III) 2010.

- ↑ See, e.g., Rwanda: How the genocide happened, BBC, 17 May 2011, which gives an estimate of 800,000, and OAU sets inquiry into Rwanda genocide, Africa Recovery, Vol. 12 1#1 (August 1998), p. 4, which estimates the number at between 500,000 and 1,000,000. Seven out of every 10 Tutsis were killed.

- ↑ Dallaire 2005, p. 386.

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-13431486

- ↑ Dallaire 2005, pp. 264–265.

- ↑ Dallaire 2005, p. 269.

- ↑ Dallaire 2005, p. 288.

- ↑ Kinzer 2008, p. 158.

- ↑ Dallaire 2005, p. 299.

- ↑ Prunier 1999, p. 268.

- 1 2 3 Dallaire 2005, p. 421.

- ↑ Dallaire 2005, p. 459.

- ↑ "Official holidays". gov.rw. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ↑ CIA 2007, p. 479.

- 1 2 BBC News (I) 2006.

- ↑ REMA 2013, p. 11.

- ↑ REMA 2013, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ ITMB Publishing 2007.

- ↑ REMA 2013, p. 7.

- ↑ REMA 2013, p. 5.

- ↑ BBC News (II) 2006.

- ↑ REMA 2013, p. 4.

- ↑ REMA 2013, p. 6.

- 1 2 REMA 2013, p. 8.

- 1 2 REMA 2013, p. 9.

- ↑ Mbanda 2014.

- ↑ The EastAfrican 2017.

- ↑ Mwai 2017.

- ↑ Google Maps (I).

- ↑ Google Maps (II).

- ↑ Google Maps (III).

- ↑ Google Maps (IV).

- ↑ The Week 2017.

- 1 2 Tabaro 2014.

- 1 2 Rough Guides 2015.

- ↑ Tumwebaze (II) 2013.

- 1 2 Malonza 2015.

- 1 2 Tashobya 2017.

- ↑ Tumwebaze (III) 2013.

- ↑ Kigali Genocide Memorial.

- ↑ http://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/191644

- ↑ Twagilimana 2015, p. 217.

- ↑ U.S. Department of State 2004.

- 1 2 3 World Meteorological Organization.

- ↑ King 2007, p. 10.

- 1 2 Strategic Foresight Group 2013, p. 29.

- 1 2 NISR (I) 2012, p. 10.

- ↑ Tumwebaze (IV) 2013.

- 1 2 REMA 2013, p. 21.

- ↑ http://rurbanafrica.ku.dk/publications/urban-briefs/rurbanafrica-state-of-the-art-report-3.pdf p2

- ↑ p3

- ↑ REMA 2013, p. 1.

- ↑ p3

- ↑ p4

- ↑ REMA 2013, p. 24.

- ↑ REMA 2013, p. viii.

- ↑ p4

- ↑ From NISR (I) 2012, p. 6: 586,123 / 1,132,686 = 51.7%

- ↑ From NISR (I) 2012, p. 6: 546,563 / 1,132,686 = 48.3%

- 1 2 REMA 2013, p. 29.

- ↑ From NISR (I) 2012, p. 64: Sum of columns up to 45-49, and divide by 1,132,686

- ↑ UNDP 2015, p. 32.

- 1 2 REMA 2013, p. 30.

- ↑ City of Kigali: Kigali Development Strategy, Final Report. Kigali: Kigali Institute of Science Technology & Management. November 2001. See pp. 31–32.

- ↑ "Administrative Map of Kigali", KigaliCity.gov.rw.

- ↑ Jane Perlez (15 August 1994), "Under the Bougainvillea, A Litany of Past Wrongs", New York Times

- ↑ "Ndayisaba elected Kigali City Mayor", Newtimes.co.rw, 27 February 2011

- ↑ "Kigali to get new mayor today", Newtimes.co.rw, 29 February 2016

- ↑ Ministry of Local Government. "Mayors Contacts" (PDF). Republic of Rwanda. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2017.

- ↑ "Pascal Nyamulinda has been elected Mayor of the City of Kigali". Kigalicity.gov.rw. City of Kigali. 2016. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "New Kigali mayor vows to boost city's recreational facilities, tourism". The New Times. May 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Itegeko rishyiraho Kaminuza y'u Rwanda (UR) rikanagena inshingano, ububasha, imiterere n'imikorere byayo/Law establishing the University of Rwanda (UR) and determining its mission, powers, organisation and functioning/Loi portant création de l'Université du Rwanda (UR) et déterminant ses missions, sa compétence, son organisation et son fonctionnement". Official Gazette of the Republic of Rwanda (Igazeti ya Leta ya Repubulika y'u Rwanda/Journal Officiel de la République du Rwanda). Republic of Rwanda Office of the Prime Minister. 23 September 2013. p. 39. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ https://www.cmu.edu/rwanda/

- ↑ "Contact Us Archived 2012-11-05 at the Wayback Machine.." Kigali Independent University. Retrieved on 28 February 2013.

- ↑ "AC Group launches Tap&Go smart payment solution for public transport". en.igihe.com. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/04/kigali-plan-rwandan-city-afford-new-homes-offices

References

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195337709.

- Associated Press (6 July 1973). "Military Coup in Rwanda Follows Tribal Dissension". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- BBC News (I) (3 January 2006). "Rwanda redrawn to reflect compass". London. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- BBC News (II) (31 March 2006). "Team reaches Nile's 'true source'". London. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (2007). The World Factbook 2007. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160785801.

- Carney, J.J. (2013). Rwanda Before the Genocide: Catholic Politics and Ethnic Discourse in the Late Colonial Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199982-27-1.

- Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (2003). The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 9781890951344.

- Dallaire, Roméo (2005). Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. London: Arrow. ISBN 978-0-09-947893-5.

- Des Forges, Alison (2011). David Newbury, ed. Defeat is the only bad news: Rwanda under Musinga, 1896–1931. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299281434.

- Dorsey, Learthen (1994). Historical Dictionary of Rwanda (1 ed.). Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810828209.

- Geary, Anthony (2003). In and Out of Focus: Images from Central Africa, 1885-1960. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780856675522.

- Google Maps (I). "University Teaching Hospital of Kigali". Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Google Maps (II). "UR College of Science and Technology". Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Google Maps (III). "National Bank of Rwanda". Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Google Maps (IV). "Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning". Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Infor Congo (Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi Information and Public Relations Office) (1958). "Ruanda Urundi / Preface by Jean-Paul Horroy, governor of Ruanda-Urundi".

- ITMB Publishing (2007). Rwanda/Burundi Travel Map. Richmond, British Columbia: International Travel Maps. ISBN 9781553413806.

- Kigali Genocide Memorial. "Kigali Genocide Memorial: Getting There". Archived from the original on 30 April 2018.

- King, David C. (2007). Rwanda (Cultures of the World). New York, N.Y.: Benchmark Books. ISBN 978-0-7614-2333-1.

- Kinzer, Stephen (2008). A Thousand Hills: Rwanda's Rebirth and the Man Who Dreamed it (Hardcover ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-12015-6.

- Linden, Ian; Linden, Jane (1977). Church and Revolution in Rwanda (illustrated ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719-00-671-5.

- Louis, William Roger (1963). Ruanda-Urundi, 1884-1919. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Malonza, Josephine (20 October 2015). "The Post-Kiyovu symmetry: A critical analysis". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2002). When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691102801.

- Mbanda, Gerald (16 September 2014). "The Legacy of Dr. Richard Kandt (Part I)". The New Times. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- Mohr, Charles (7 July 1973). "Rwanda Coup Traced to Area Rivalry and Poverty". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Munyakazi, Augustine; Ntagaramba, Johnson Funga (2005). Atlas of Rwanda (in French). Oxford: Macmillan Education. ISBN 0-333-95451-3.

- Mwai, Collins (26 October 2017). "Tourism and hospitality establishments get star grading". The New Times. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) (I) (2012). "Population size, structure and distribution". Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Ntagungura, Godfrey (20 May 2011). "The history of City of Kigali". The New Times.

- Prunier, Gérard (1999). The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide (2nd ed.). Kampala: Fountain Publishers Limited. ISBN 978-9970-02-089-8.

- Rough Guides (15 May 2015). "Nyamirambo: Kigali's coolest neighbourhood". Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- Rwanda Development Board. "Muhazi". RwandaTourism.com. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- Rwanda Environment Management Authority (REMA) (2013). "Kigali: State of Environment and Outlook Report 2013" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Strategic Foresight Group (2013). "Blue Peace for the Nile" (PDF). Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Tabaro, Jean de la Croix (24 July 2014). "Know Your History: The birth of Nyamirambo". The New Times. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- The EastAfrican (26 January 2017). "Kigali businesses brace for residential to city centre move". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- The Week (21 August 2017). "Gateway to gorillas: A guide to Kigali". Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Tashobya, Athan (11 October 2017). "PHOTOS: The changing face of Lower Kiyovu". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Tumwebaze, Peterson (I) (20 May 2011). "The history of City of Kigali". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Tumwebaze, Peterson (II) (28 June 2013). "Nyabugogo: Where idlers lurk!". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Tumwebaze, Peterson (III) (23 May 2013). "Kabagali: The raggedy side of Kacyiru". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Tumwebaze, Peterson (IV) (26 July 2007). "Kigali, vast area through 100 years". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Twagilimana, Aimable (2015). Historical Dictionary of Rwanda (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442255913.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2015). "Population projections" (PDF). Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- United States Department of State (11 July 1973). "Cable: Rwanda Coup". Public Library of US Diplomacy (Wikileaks). Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- United States Department of State (2004). "Background Note: Rwanda". Background Notes. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- World Meteorological Organization. "World Weather Information Service – Kigali". Retrieved 12 November 2015.

External links

![]()

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kigali. |