Kinshasa

| Kinshasa Ville de Kinshasa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City Province | |||

|

City сentre | |||

| |||

|

Nickname(s): Kin la belle (English: Kin the beautiful) | |||

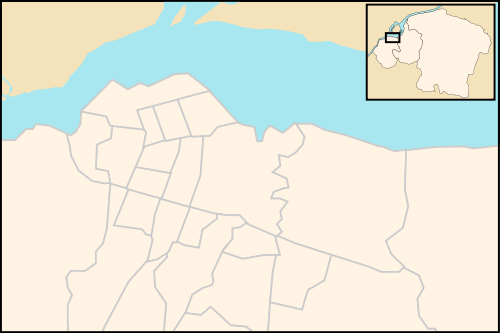

_-_Kinshasa.svg.png) DRC, highlighting the city-province of Kinshasa | |||

Kinshasa DRC, highlighting the city-province of Kinshasa  Kinshasa Kinshasa (Africa) | |||

| Coordinates: 4°19′30″S 15°19′20″E / 4.32500°S 15.32222°ECoordinates: 4°19′30″S 15°19′20″E / 4.32500°S 15.32222°E | |||

| Country | Democratic Republic of the Congo | ||

| Founded | 1881 | ||

| Administrative HQ | La Gombe | ||

| Communes | |||

| Government | |||

| • Governor | André Kimbuta | ||

| Area[1] | |||

| • City-province | 9,965 km2 (3,848 sq mi) | ||

| • Urban[2] | 600 km2 (200 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 240 m (790 ft) | ||

| Population (2017)[2] | |||

| • Urban | 11,855,000 | ||

| • Urban density | 20,000/km2 (51,000/sq mi) | ||

| • Language | French, Lingala | ||

| Time zone | GMT+1 | ||

| Area code(s) | 243 + 9 | ||

| HDI | 0.58 Medium (2012)[3] | ||

| Website | www.kinshasa.cd | ||

Kinshasa (/kɪnˈʃɑːsə/; French: [kinʃasa]; formerly Léopoldville (French: Léopoldville or Dutch ![]()

Once a site of fishing and trading villages, Kinshasa is now a megacity with an estimated population of more than 11 million.[2] It faces Brazzaville, the capital of the neighbouring Republic of the Congo, which can be seen in the distance across the wide Congo River, making them the world's second-closest pair of capital cities after Rome and Vatican City. The city of Kinshasa is also one of the DRC's 26 provinces. Because the administrative boundaries of the city-province cover a vast area, over 90 percent of the city-province's land is rural in nature, and the urban area occupies a small but expanding section on the western side.[4]

Kinshasa is Africa's third-largest urban area after Cairo and Lagos.[2] It is also the world's largest Francophone urban area (recently surpassing Paris in population),[5][6] with French being the language of government, schools, newspapers, public services, and high-end commerce in the city, while Lingala is used as a lingua franca in the street.[7] Kinshasa hosted the 14th Francophonie Summit in October 2012.[8]

Residents of Kinshasa are known as Kinois (in French and sometimes in English) or Kinshasans (English). The indigenous people of the area include the Humbu and Teke.

History

.png)

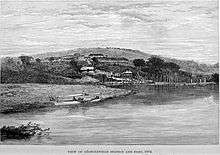

The city was founded as a trading post by Henry Morton Stanley in 1881. It was named Léopoldville in honour of King Leopold II of Belgium, who controlled the vast territory that is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, not as a colony but as a private property. The post flourished as the first navigable port on the Congo River above Livingstone Falls, a series of rapids over 300 kilometres (190 miles) below Leopoldville. At first, all goods arriving by sea or being sent by sea had to be carried by porters between Léopoldville and Matadi, the port below the rapids and 150 km (93 mi) from the coast. The completion of the Matadi-Kinshasa portage railway, in 1898, provided an alternative route around the rapids and sparked the rapid development of Léopoldville. In 1914, a pipeline was installed so that crude oil could be transported from Matadi to the upriver steamers in Leopoldville.[9] By 1923, the city was elevated to capital of the Belgian Congo, replacing the town of Boma in the Congo estuary.[9] The town, nicknamed "Léo" or "Leopold", became a commercial centre and grew rapidly during the colonial period.

After gaining its independence on 30th June 1960, following riots in 1959, the Republic of the Congo elected its first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. Lumumba's determination to have full control over Congo's resources to improve the living conditions of his people was perceived as a threat to Western interests. This being the height of the Cold War, the U.S. and Belgium did not want to lose control of the strategic wealth of the Congo, in particular its uranium. Less than a year after Lumumba's election, the Belgians and the U.S. bought the support of his Congolese rivals and set in motion the events that culminated in Lumumba's assassination. In 1965, with the help of the U.S. and Belgium, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu seized power in the Congo. He initiated a policy of "Africanizing" the names of people and places in the country. In 1966, Léopoldville was renamed Kinshasa, for a village named Kinshasa that once stood near the site, today Kinshasa (commune). The city grew rapidly under Mobutu, drawing people from across the country who came in search of their fortunes or to escape ethnic strife elsewhere, thus adding to the many ethnicities and languages already found there.

In the 1990s, a rebel uprising began, which, by 1997, had brought down the regime of Mobutu.[9] Kinshasa suffered greatly from Mobutu's excesses, mass corruption, nepotism and the civil war that led to his downfall. Nevertheless, it is still a major cultural and intellectual centre for Central Africa, with a flourishing community of musicians and artists. It is also the country's major industrial centre, processing many of the natural products brought from the interior. The city has recently had to fend off rioting soldiers, who were protesting the government's failure to pay them.

Joseph Kabila, president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo since 2001, is not overly popular in Kinshasa.[10] Violence broke out following the announcement of Kabila's victory in the contested election of 2006; the European Union deployed troops (EUFOR RD Congo) to join the UN force in the city. The announcement in 2016 that a new election would be delayed two years led to large protests in September and in December which involved barricades in the streets and left dozens of people dead. Schools and businesses were closed down.[11][12]

Geography

Kinshasa is a city of sharp contrasts, with affluent residential and commercial areas and three universities alongside sprawling slums. It is located along the south bank of the Congo River, downstream on the Pool Malebo[13] and directly opposite the city of Brazzaville, capital of the Republic of the Congo. The Congo river is the second longest river in Africa after the Nile, and has the continent's greatest discharge. As a waterway it provides a means of transport for much of the Congo basin; it is navigable for large river barges between Kinshasa and Kisangani, and many of its tributaries are also navigable. The river is an important source of hydroelectric power, and downstream from Kinshasa it has the potential to generate power equivalent to the usage of roughly half of Africa's population.[14]

The older and wealthier part of the city (ville basse) is located on a flat area of alluvial sand and clay near the river, while many newer areas are found on the eroding red soil of surrounding hills.[1][10] Older parts of the city were laid out on a geometric pattern, with de facto racial segregation becoming de jure in 1929 as the European and African neighborhoods grew closer together. City plans of the 1920s–1950s featured a cordon sanitaire or buffer between the white and black neighborhoods, which included the central market as well as parks and gardens for Europeans.[15]

Urban planning in post-independence Kinshasa has not been extensive. The Mission Française d'Urbanisme drew up some plans in the 1960s which envisioned a greater role for automobile transportation but did not predict the city's significant population growth. Thus much of the urban structure has developed without guidance from a master plan. According to UN-Habitat, the city is expanding by eight square kilometers per year. It describes many of the new neighborhoods as slums, built in unsafe conditions with inadequate infrastructure.[16] Nevertheless spontaneously developed areas have in many cases extended the orthogonal streets from the original city.[13]

Administrative divisions

Kinshasa is both a city (ville in French) and a province, one of the 26 provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Its status is thus similar to that of Paris which is both a city and one of the 101 departments of France. The ville-province of Kinshasa is divided into four districts which are further divided into 24 communes (municipalities), which in turn contain various quarters (332 in total).[13] Maluku, the rural province to the east of the urban area, accounts for 79% of the 9.965 km2 total land area of the ville-province,[4] with a population of 200,000–300,000.[13]

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

Abbreviations : Kal. (Kalamu), Kin. (Kinshasa), K.-V. (Kasa-Vubu), Ling. (Lingwala), Ng.-Ng. (Ngiri-Ngiri) |

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Kinshasa has a Tropical wet and dry climate. Its lengthy rainy season spans from October through May, with a relatively short dry season, between June and September. Kinshasa lies south of the equator, so its dry season begins around its "winter" solstice, which is in June. This is in contrast to African cities further north featuring this climate where the dry season typically begins around January. Kinshasa's dry season is slightly cooler than its wet season, though temperatures remain relatively constant throughout the year.

| Climate data for Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36 (97) |

36 (97) |

38 (100) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

32 (90) |

33 (91) |

35 (95) |

35 (95) |

37 (99) |

34 (93) |

38 (100) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.6 (87.1) |

31.3 (88.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.1 (88) |

28.8 (83.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

28.9 (84) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.1 (88) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.1 (86.2) |

30.4 (86.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.9 (78.6) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

23.7 (74.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.2 (70.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 18 (64) |

20 (68) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

18 (64) |

15 (59) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

16 (61) |

17 (63) |

18 (64) |

16 (61) |

10 (50) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 163 (6.42) |

165 (6.5) |

221 (8.7) |

238 (9.37) |

142 (5.59) |

9 (0.35) |

5 (0.2) |

2 (0.08) |

49 (1.93) |

98 (3.86) |

247 (9.72) |

143 (5.63) |

1,482 (58.35) |

| Average precipitation days | 12 | 12 | 14 | 17 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 10 | 16 | 14 | 115 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 82 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 81 | 79 | 74 | 74 | 79 | 83 | 83 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 136 | 141 | 164 | 153 | 164 | 144 | 133 | 155 | 138 | 149 | 135 | 127 | 1,739 |

| Source #1: Climate-Data.org (tempetature)[17] Weatherbase (extremes)[18] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Danish Meteorological Institute (precipitation, sun, and humidity)[19] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

An official census conducted in 1984 counted 2.6 million residents.[20] Since then, all estimates are extrapolations. The estimates for 2005 fell in a range between 5.3 million and 7.3 million.[13]

According to UN-Habitat, 390,000 people immigrate to Kinshasa annually, fleeing warfare and seeking economic opportunity. Many float on barges down the Congo River.[21]

Government and politics

The head of Kinshasa ville-province has the title of Gouverneur. André Kimbuta has been governor since 2007. Each commune has its own Bourgmestre.[13]

Although political power in the DRC is fragmented, Kinshasa as the national capital represents the official center of sovereignty, and thus of access to international organizations and financing, and of political powers such as the right to issue passports.[10] Kinshasa is also the primate city of the DRC with a population several times larger than the next-largest city, Lubumbashi.[22][16]

The United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, known by its French acronym MONUSCO (formerly MONUC) makes its headquarters in Kinshasa. In 2016 the UN placed more peacekeepers on active duty in Kinshasa in response to the recent unrest against Kabila.[23] Critics, including recently the US ambassador to the UN,[24] have accused the peacekeeping mission of supporting a corrupt government.[25][26]

Other non-governmental organizations play significant roles in local governance.[27] The Belgian development agency (Coopération technique belge; CTB) since 2006 sponsors the Programme d’Appui aux Initiatives de Développement Communautaire (Paideco), a 6-million-euro program aimed at economic development. It began work in Kimbanseke, a hill commune with population verging on one million.[28]

Economy

Big manufacturing companies such as Marsavco S.A.R.L., All Pack Industries and Angel Cosmetics are located in the centre of town (Gombe) in Kinshasa.

There are many other industries, such as Trust Merchant Bank, located in the heart of the city. Food processing is a major industry, and construction and other service industries also play a significant role in the economy.[29]

Although home to only 13% of the DRC's population, Kinshasa accounts for 85% of the Congolese economy as measured by gross domestic product.[16] A 2004 investigation found 70% of inhabitants employed informally, 17% in the public sector, 9% in the formal private sector, and 3% other, of a total 976,000 workers. Most new jobs are classified as informal.[13]

The People's Republic of China has been heavily involved in the Congo since the 1970s, when they financed the construction of the Palais du Peuple and backed the government against rebels in the Shaba war. In 2007–2008 China and Congo signed an agreement for an $8.5 billion loan for infrastructure development.[30] Chinese entrepreneurs are gaining an increasing share of local marketplaces in Kinshasa, displacing in the process formerly successful Congolese, West African, Indian, and Lebanese merchants.[31]

Mean household spending in 2005 was the equivalent of US$2,150, amounting to $1 per day per person. The median household spending was $1,555, 66 cents per person per day. Among the poor, more than half of this spending goes to food, especially bread and cereal.[13]

Social issues

Crime and punishment

Since the Second Congo War, the city has been striving to recover from disorder, with many youth gangs hailing from Kinshasa's slums.[32] The U.S. State Department in 2010 informed travelers that Kinshasa and other major Congolese cities are generally safe for daytime travel, but to beware of robbers, especially in traffic jams and in areas near hotels and stores.[33]

Some sources say that Kinshasa is extremely dangerous, with one source giving a homicide rate of 112 per 100,000 people per year.[34] Another source cites a homicide rate of 12.3 per 100,000.[35] By some accounts, crime in Kinshasa is not so rampant, due to relatively good relations among residents and perhaps to the severity with which even petty crime is punished.[10]

While the military and National Police operate their own jails in Kinshasa, the main detention facility under the jurisdiction of the local courts is the Kinshasa Penitentiary and Re-education center in Malaka. This prison houses more than double its nominal capacity of 1,000 inmates. The Congolese military intelligence organization, Détection Militaire des Activités Anti-Patrie (DEMIAP) operates the Ouagadougou prison in Kintambo commune with notorious cruelty.[35][36]

By 2017 the population of Malaka prison was reported at 7,000–8,000. Of these, 3,600–4,600 escaped in a jailbreak in May.[37][38]

Street children

Street children[39][40] or "Shegués", often orphaned, are subject to abuse by the police and military. Of the estimated 20,000 children living on Kinshasa's streets, almost a quarter are beggars, some are street vendors and about a third have some kind of employment.[41] Some have fled from physically abusive families, notably step-parents, others were expelled from their families as they were believed to be witches,[42] and have become outcasts.[43][44][45] Previously a significant number were civil war orphans.

Street children are mainly boys,[46] but the percentage of girls is increasing according to UNICEF. Ndako ya Biso provides support for street children, including overnight accommodation for girls.[47] There are also second generation street children[48]: "they referred to their sub-culture of violence as kindoubill"[49].

These children have been the object of considerable outside study.[50]

Education

Kinshasa is home to several higher-level education institutes, covering a wide range of specialities, from civil engineering to nursing and journalism. The city is also home to three large universities and an arts school:

- Académie de Design (AD)

- Institut Supérieur d'Architecture et Urbanisme

- Université Panafricaine du Congo (UPC)

- University of Kinshasa

- Université Libre de Kinshasa

- Université Catholique du Congo

- Congo Protestant University

- National Pedagogy University

- National Institute of Arts

- Allhadeff School

- Institut Supérieur de Publicité et Médias

- Lycée Prince de Liège / Prins van Luik School (primary and secondary education, Belgian curriculum)

- Centre for Health Training (CEFA)[51]

In 2005, 93% of children over six attended school and 70% of people over 15 were literate in French.

Health and medicine

There are twenty hospitals in Kinshasa, plus various medical centres and polyclinics.[52] In 1997, Dikembe Mutombo built a 300-bed hospital near his home town of Kinshasa.

Since 1991, Monkole Hospital is operating as a non-profit health institution collaborating with the Health Department as district hospital in Kinshasa. Directed by Pr Léon Tshilolo, paediatrician and haematologist, Monkole Hospital opened a 150-bed building in 2012 with improved clinical services as laboratory, diagnostic radiology, intensive care, neonatal unit, family medicine, emergencies unit and a larger surgical area.

Culture

Kinshasa is the home to much of the Congo's intelligentsia, including a political class which developed during the Mobutu era.[53]

Kinshasa has a flourishing music scene which since the 1960s has operated under the patronage of the city's elite.[10] The Orchestre Symphonique Kimbanguiste, formed in 1994, began using improved musical instruments and has since grown in means and reputation.[54]

In 1974, Kinshasa hosted The Rumble in the Jungle boxing match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, in which Ali defeated Foreman, to regain the World Heavyweight title.

A pop culture ideal type in Kinshasa is the mikiliste, a fashionable person with money who has traveled to Europe. Adrien Mombele, a.k.a. Stervos Niarcos, and musician Papa Wemba, were an early exemplar of the mikiliste style.[10] La Sape, a linked cultural trend also described as dandyism, involves wearing of flamboyant clothing.

Many Kinois have a negative view of the city, expressing nostalgia for the rural way of life, and a stronger association with the Congolese nation than with Kinshasa.[53]

Media

.jpg)

Kinshasa is home to a large number of media outlets, including multiple radio and television stations that broadcast to nearly the entire country, including state-run Radio-Television Nationale Congolaise (RTNC) and privately run Digital Congo and Raga TV. The private channel RTGA is also based in Kinshasa.

Several national radio stations, including La Voix du Congo, which is operated by RTNC, MONUC-backed Radio Okapi and Raga FM are based in Kinshasa, as well as numerous local stations. The BBC is also available in Kinshasa on 92.6 FM.[56]

The state-controlled Agence Congolaise de Presse news agency is based in Kinshasa, as well as several daily and weekly newspapers and news websites, including L'Avenir (daily), La Conscience, LeCongolais (online),L'Observateur (daily), Le Phare, Le Potentiel, and Le Soft.[57]

Most of the media uses French and Lingala to a large extent; very few use the other national languages.

Language

The official language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, of which Kinshasa is the capital, is French (See: Kinshasa French vocabulary). Kinshasa is the largest officially Francophone city in the world[5][58][59] although Lingala is widely used as a spoken language. French is the language of street signs, posters, newspapers, government documents, schools; it dominates plays, television, and the press, and it is used in vertical relationships among people of different social classes. People of the same class, however, speak the Congolese languages (Kikongo, Lingala, Tshiluba or Swahili) among themselves.[60]

Sports

Sports, especially football and martial arts are popular in Kinshasa. The Vita Club, now owned by General Gabriel Amisi Kumba frequently draws large crowds, enthusiastic and sometimes rowdy, to the Stade des Martyrs. Dojos are popular and their owners influential.[10]

Buildings and institutions

Kinshasa is home to the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo including:

- the Palais de la Nation, home of the President, in Gombe;

- the Palais du Peuple, meeting place of both houses of Parliament, Senate and National Assembly, in Lingwala;

- the Cité de l’OUA, built for the Organization of African Unity in the 1970s and now serving government functions, in Ngaliema.

The Central Bank of the Congo has its headquarters on Boulevard Colonel Tshatshi, across the street from the Mausoleum of Laurent Kabila and the presidential palace.

The quartier Matonge is known regionally for its nightlife.

Notable features of the city include the Gecamines Commercial Building (formerly SOZACOM) and Hotel Memling skyscrapers; L'ONATRA, the impressive building of the Ministry of Transport; the central market; the Kinshasa Museum; and the Kinshasa Fine Arts Academy. The face of Kinshasa is changing as new buildings are being built on the Boulevard du 30 Juin: Crown Tower (on Batetela) and Congofutur Tower.

Kinshasa is home to the country's national stadium, the Stade des Martyrs (Stadium of the Martyrs).

Infrastructure and housing

The city's infrastructure for running water and electricity is generally in bad shape.[61] The electrical network is in disrepair to the extent that prolonged and periodic blackouts are normal, and exposed lines sometimes electrify puddles of rainwater.[10][13]

Regideso, the national public company with primary responsibility for water supply in the Congo, serves Kinshasa only incompletely, and not with uniformly perfect quality. Other areas are served by decentralized Associations des Usagers des Réseau d’Eau Potable (ASUREPs).[20] Gombe uses water at a high rate (306 liters per day per inhabitant) compared to other communes (from 71 l/d/i in Kintambo down to 2 l/d/i in Kimbanseke).[13]

The city is estimated to produce 6,300 m3 of trash and 1,300 m3 of industrial waste per day.[13]

The housing market has seen rising prices and rents since the 1980s. Houses and apartments in the central area are expensive, with houses selling for a million dollars and apartments going for $5000 per month. High prices have spread outward from the central area as owners and renters move out of the most expensive part of the city. Gated communities and shopping malls, built with foreign capital and technical expertise, began to appear in 2006. Urban renewal projects have led in some cases to violent conflict and displacement.[10][62] The high prices leave incoming refugees with few options for settlement besides illegal shantytowns such as Pakadjuma.[21]

In 2005, 55% of households had televisions and 43% had mobile phones. 11% had refrigerators and 5% had cars.[13]

Transport

- See also: List of streets in Kinshasa (in French)

The ville-province has 5000 km of roadways, 10% of which are paved. The Boulevard du 30 Juin (Boulevard of 30 June) links the main areas of the central district of the city. Other roads also converge on Gombe. The East-West road network linking the more distant neighborhoods is weak and thus transit through much of the city is difficult.[13] The quality of roads has improved somewhat, developed in part with loans from China, since a nadir in year 2000.[10]

Several private companies serve the city, among them the Urban Transport Company (STUC) and the Public City train (12 cars in 2002). The bus lines are:

- Gare centrale – Kingasani (municipality of Kimbanseke, reopened in September 2005);

- Kingasani – Marché central

- Matete – Royale (reopened in June 2006);

- Matete – UPN (reopened in June 2006);

- Rond-point Ngaba – UPN (reopened in June 2006).

- Rond-point Victoire – clinique Ngliema (opened in March 2007)

Other companies also provide public transport: Urbaco, Tshatu Trans, Socogetra, Gesac and MB Sprl. The city buses carry up to 67,000 passengers per day. Several companies operate taxis and taxi-buses. Also available are fula-fula (trucks adapted to carry passengers).[63] The majority (95.8 percent) of transport is provided by individuals.

Air

The city has two airports: N'djili Airport (FIH) is the main airport with connections to other African countries as well as to Brussels, Paris and some other destinations. N'Dolo Airport, located close to the city centre, is used for domestic flights only with small turboprop aircraft. Several international airlines serve Ndjili Airport including Kenya Airways, Air Zimbabwe, South African Airways, Ethiopian Airlines, Brussels Airlines, Air France and Turkish Airlines. As of June 2016 DR Congo has two national airlines, Congo Airways, formed with the help of Air France, and Air Kasaï. Both offer scheduled flights from Kinshasa to a limited number of cities inside DR Congo.

Rail

.jpg)

The Matadi–Kinshasa Railway connects Kinshasa with Matadi, Congo's Atlantic port. The line reopened in September 2015 after around a decade without regular service. As of April 2016, there was one passenger trip per week along the line, which travels the 350 kilometres (220 miles) between Kinshasa and Matadi every Saturday in about 7 hours; more frequent service was planned.[64] Brazzaville in the neighbouring Republic of Congo is connected to its Atlantic port at Pointe-Noire via the Congo–Ocean Railway.

ONATRA operates three lines of urban railways linking the town centre, which goes to Bas-Congo.[65]

- The main line linking the Central Station to the N'djili Airport has 9 stations: Central Station, Ndolo, Amicongo, Uzam, Masina / Petro-Congo, Masina wireless Masina / Mapela, Masina / Neighborhood III, Masina / Siforco Camp Badara and Ndjili airport.

- The second line connects the Central Station in Kasangulu in Bas-Congo, through Matete, Riflart and Kimwenza.

- The third line at the Central Station Kinsuka-pumping in the town of Ngaliema.

In 2007, Belgium assisted in a renovation of the country's internal rail network.[66] This improved service to Kintambo, Ndolo, Limete, Lemba, Kasangulu, Gombe, Ndjili and Masina. During the early years of the 21st century, the city's planners considered creating a tramway in collaboration with public transport in Brussels (STIB), whose work would start in 2009. That work has not moved beyond the planning stage, partly due to lack of a sufficient electrical supply.[67][68]

External transport

Kinshasa is the major river port of the Congo. The port, called 'Le Beach Ngobila' extends for about 7 km (4 mi) along the river, comprising scores of quays and jetties with hundreds of boats and barges tied up. Ferries cross the river to Brazzaville, a distance of about 4 km (2 mi). River transport also connects to dozens of ports upstream, such as Kisangani and Bangui.

There are road and rail links to Matadi, the sea port in the Congo estuary 150 km (93 mi) from the Atlantic Ocean.

There are no rail links from Kinshasa further inland, and road connections to much of the rest of the country are few and in poor condition.

Notable people

.jpg)

- Emmanuel Weyi, Congolese entrepreneur

- Joseph Damien Tshatshi, colonel in the Armée Nationale Congolaise

Academics

Politicians

- Justin Marie Bomboko

- David Norris, scholar and politician, 2011 election candidate for President of Ireland

Athletes

- D. J. Mbenga, professional basketball player for the Los Angeles Lakers in the US National Basketball Association

- Emmanuel Mudiay, professional basketball player of the Denver Nuggets in the US National Basketball Association

- Christian Eyenga, professional basketball player and 2009 first round draft choice for the Cleveland Cavaliers in the US National Basketball Association

- Dikembe Mutombo, retired professional basketball player

- Christian M'Pumbu, professional mixed martial arts fighter and Bellator Fighting Championships World Champion

- Guylain Ndumbu-Nsungu, former Sheffield Wednesday football player

- Jeremy Bokila, professional football player, son of Ndingi Bokila Mandjombolo

- Claude Makélélé, professional football player and current manager

- Steve Mandanda, professional footballer who plays for Crystal Palace and the France national football team

- Ariza Makukula, naturalised Portuguese retired professional football player

- José Bosingwa, naturalised Portuguese football player

- Leroy Lita, professional football player

- Fabrice Muamba, former professional footballer who played for Bolton Wanderers in the Premier League

- Tim Biakabutuka, former professional American football player

- Kazenga LuaLua, professional football player for Brighton & Hove Albion F.C.

- Lomana LuaLua, professional football player for Al-Arabi in Qatar

- Mwamba Kazadi, former professional football player who won the 1973 "African Footballer of the Year" award

- Péguy Luyindula, professional football player for Paris Saint-Germain in Ligue 1

- Hérita Ilunga, professional football player

- Gary Kikaya, retired Olympic 400-metre runner

- Patrick Kabongo, professional football player for the Edmonton Eskimos of the Canadian Football League

- Youssouf Mulumbu, professional footballer for Norwich City

- Danny Mwanga, professional footballer for the Philadelphia Union

- Blaise Nkufo, professional footballer for Switzerland

- Gabriel Zakuani, professional football player for Peterborough United of The Football League in England

- Steve Zakuani, professional football player for the Seattle Sounders of Major League Soccer in the United States

- Occupé Bayenga, professional football player who currently plays in Universidad de Concepción, Chilean Primera División

- Christian Benteke, professional football player for Crystal Palace F.C. of the Premier League and the Belgium national football team

- Jody Lukoki, professional football player for Ludogorets Razgrad in the Bulgarian First League and the DR Congo national football team

- Toto Nsiala, professional football player for Ipswich Town

Artists

- Maître Gims, rapper-singer

- Jimmy Omonga, singer-songwriter

- JB Mpiana, singer-songwriter

- Werrason, singer-songwriter

- Felix Wazekwa, singer-songwriter

- Lokua Kanza, singer-songwriter

- Ya Kid K, hip-hop artist

- Leki, R&B artist

- Jessy Matador, singer

- Odette Krempin, fashion designer

- Kaysha, hip-hop artist

- Merveille Lukeba, professional actor for the series Skins on E4

- Mohombi, Pop, Hip Hop artist

- Fally Ipupa, singer-songwriter

- Koffi Olomide, singer- songwriter

- Papa Wemba, singer- songwriter

- Tembo Kash, cartoonist

Twin towns

Kinshasa is twinned with:

- Brazzaville

- Johannesburg

- Ankara, since 2005[71]

See also

Films about Kinshasa

References

- 1 2 Matthieu Kayembe Wa Kayembe, Mathieu De Maeyer et Eléonore Wolff, "Cartographie de la croissance urbaine de Kinshasa (R.D. Congo) entre 1995 et 2005 par télédétection satellitaire à haute résolution", Belgeo 3–4, 2009 ; doi:10.4000/belgeo.7349.

- 1 2 3 4 "DemographiaWorld Urban Areas – 13th Annual Edition" (PDF). Demographia. April 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ "State of the World's Cities 2012/2013" (PDF). UN Habitat. 2013. p. 18. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Géographie de Kinshasa". Ville de Kinshasa. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Populations of 150 Largest Cities in the World". World Atlas. 7 March 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ↑ "Time series of the population of the 30 largest urban agglomerations in 2011 ranked by population size, 1950–2025". United Nations, Population Division. Archived from the original (XLS) on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ Cécile B. Vigouroux & Salikoko S. Mufwene (2008). Globalization and Language Vitality: Perspectives from Africa, pp. 103 & 109. ISBN 9780826495150. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ "XIVe Sommet de la Francophonie". OIF. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Kinshasa – national capital, Democratic Republic of the Congo". britannica.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Joe Trapido, "Kinshasa's Theater of Power", New Left Review 98, March/April 2016.

- ↑ "DR Congo election: 17 dead in anti-Kabila protests", BBC, 19 September 2016.

- ↑ Merritt Kennedy, "Congo A 'Powder Keg' As Security Forces Crack Down On Whistling Demonstrators", NPR, 21 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Jean Flouriot, "Kinshasa 2005. Trente ans après la publication de l’Atlas de Kinshasa", Les Cahiers d’Outre-Mer 261, January–March 2013; doi:10.4000/com.6770.

- ↑ Wachter, Sarah J. (19 June 2007). "Giant dam projects aim to transform African power supplies". New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Luce Beeckmans & Liora Bigon, "The making of the central markets of Dakar and Kinshasa: from colonial origins to the post-colonial period”; Urban History 43(3), 2016; doi:10.1017/S0963926815000188.

- 1 2 3 Innocent Chirisa, Abraham Rajab Matamanda, & Liaison Mukarwi, "Desired and Achieved Urbanisation in Africa: In Search of Appropriate Tooling for a Sustainable Transformation”; in Umar Benna & Indo Benna, eds., Urbanization and Its Impact on Socio-Economic Growth in Developing Regions; IGI Global, 2017, ISBN 9781522526605; pp. 101–102.

- ↑ "Climate: Kinshasa". AmbiWeb GmbH. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ "KINSHASA, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO". Weatherbase. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ "STATIONSNUMMER 64210" (PDF). Danish Meteorological Institute. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- 1 2 Florent Bédécarrats, Oriane Laufente-Sampietro, Martin Leménager, & Dominique Lukono Sowa, "Building commons to cope with chaotic urbanization? Performance and sustainability of decentralized water services in the outskirts of Kinshasa"; Journal of Hydrology (online 15 July 2016); doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.07.023.

- 1 2 Gianluca Iazzolino, "Kinshasa, megalopolis of 12 million souls, expanding furiously on super-charged growth Archived 9 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine."; Mail & Guardian Africa, 2 April 2016.

- ↑ Pain (1984), p. 56.

- ↑ "UN beefs up peacekeeping force in DR Congo capital", East African / AFP, 19 October 2016.

- ↑ "US Ambassador: UN Aiding 'Corrupt' Government in Congo", VOA News, 29 March 2017.

- ↑ Terry M. Mays, Historical Dictionary of Multinational Peacekeeping, Third Edition; Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2011; p. 330.

- ↑ "UN troops open fire in Kinshasa", BBC, 3 June 2004.

- ↑ Inge Wagemakers, Oracle Makangu Diki, & Tom De Herdt, "Lutte Foncière dans la Ville: Gouvernance de la terre agricole urbaine à Kinshasa"; L’Afrique des grands lacs: Annuaire 2009–2010.

- ↑ Inge Wagemakers & Jean-Nicholas BCH, "Les Défis de l’Intervention: Programme d'aide internationale et dynamiques de gouvernance locale dans le Kinshasa périurbain"; Politique africaine 2013/1 no. 129; doi:10.3917/polaf.129.0113.

- ↑ "Kinshasa – national capital, Democratic Republic of the Congo". britannica.com.

- ↑ Emizet Francois Kisangani, Scott F. Bobb, "China, People's Republic of, Relations with"; Historical Dictionary of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2010; pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Nuah M. Makungo, "Is the Democratic Republic of Congo being Globalized by China? The Case of Small Commerce at Kinshasa Central Market", Quarterly Journal of Chinese Studies 2(1), 2012.

- ↑ Jonny Hong, "Gang crime threatens the future of Congo's capital", Reuters, 19 June 2013.

- ↑ "U.S. Dept. of State – Congo, Democratic Republic of the Country Specific Information". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Bruce Baker. "Nonstate Policing: Expanding the Scope for Tackling Africa's Urban Violence" (PDF). Africacenter.org. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- 1 2 O. Oko Elechi and Angela R. Morris, “Congo, Democratic Republic of the (Congo-Kinshasa)”; in Mahesh K. Nalla & Graeme R. Newman (eds.), Crime and Punishment around the World, Volume 1: Africa and the Middle East; Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2010; pp. 53–56.

- ↑ Prisons in the Democratic Republic of Congo, ed. Ryan Nelson, Refugee Documentation Center, Ireland; May 2002.

- ↑ Laurent Larcher, "Des milliers de détenus s’évadent de la prison de Kinshasa en RD-Congo", La Croix, 18 May 2017.

- ↑ "Evasion à la prison de Makala en RDC: plus de 4600 détenus seraient en fuite", RFI, 18 May 2017.

- ↑ "Blogsome". blogsome.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Manson, Katrina (22 July 2010). "Congo's children battle witchcraft accusations". Reuters. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ "Street Children in Kinshasa". Africa Action. 8 July 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ "A night on the streets with Kinshasa's 'child witches'". War Child UK – Warchild.org.uk. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ "Danballuff – Children of Congo: From War to Witches(video)". Gvnet.com. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ "Africa Feature: Around 20,000 street children wander in Kinshasa". English.people.com.cn. 1 June 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ "Prevalence, Abuse & Exploitation of Street Children". Gvnet.com. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ "At the centre – Street Childrens". streetchildrenofkinshasa.com.

- ↑ Ross, Aaron. "Beaten and discarded, Congo street children are strangers to mining boom". reuters.com.

- ↑ "What Future? Street Children in the Democratic Republic of Congo: IV. Background". hrw.org.

- ↑ Charles-Didier Gondola, Tropical Cowboys: Westerns, Violence, and Masculinity among the Young Bills of Kinshasa, Afrique & histoire 2009/1 (vol. 7), p. 77.

- ↑ Camille Dugrand, “Subvertir l’ordre? Les ambivalences de l’expression politique des Shégués de Kinshasa”; Revue Tiers Monde 4(228), 2016; doi:10.3917/rtm.228.0045. "Figures incontournables de l’urbanité kinoise, les Shégués ont fait l’objet de plusieurs travaux scientifiques (Biaya, 1997, 2000 ; De Boeck, 2000, 2005 ; Geenen, 2009)."

- ↑ "Cefacongo.org". Cefacongo.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ "Provincial Health Division of Kinshasa" Archived 14 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. African Development Information Services

- 1 2 Bill Freund, "City and Nation in an African Context: National Identity in Kinshasa”; Journal of Urban History 38(5), 2012; doi:10.1177/0096144212449141.

- ↑ Andy Morgan, "The scratch orchestra of Kinshasa", The Guardian 9 May 2013.

- ↑ Mohamed Hassim Keita, "Congolese journalists protest insecurity, threats", Committee to Protect Journalists, 8 October 2009.

- ↑ "Democratic Republic of Congo country profile – Media". BBC News. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ "Countries: Democatric Republic of the Congo: News" (Archive). [sic] Stanford University Libraries & Academic Information Resources. Retrieved on 28 April 2014.

- ↑ Nadeau, Jean-Benoit (2006). The Story of French. St. Martin's Press. p. 301; 483. ISBN 9780312341831. The world's second-largest francophone city is not Montreal, Dakar, or Algiers, as many people would assume, but Kinshasa, capital of the former Zaïre.

- ↑ Trefon, Theodore (2004). Reinventing Order in the Congo: How People Respond to State Failure in Kinshasa. London and New York: Zed Books. p. 7. ISBN 9781842774915. Retrieved 31 May 2009. A third factor is simply a demographic one. At least one in ten Congolese live in Kinshasa. With its population exceeding eleven million, it is the second-largest city in sub-Saharan Africa (after Lagos). It is also the second-largest French-speaking city in the world, according to Paris (even though only a small percentage of Kinois speak French correctly),

- ↑ Manning, Patrick (1998). Francophone sub-Saharan Africa: Democracy and Dependence, 1985–1995. London and New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 189. ISBN 9780521645195. Retrieved 31 May 2009. While the culture is dominated by the Francophonie, a complex multilingualism is present in Kinshasa. Many in the francophonie of the 1980s labelled Zaïre as the second-largest francophone country, and Kinshasa as the second-largest francophone city. Yet Zaïre seemed unlikely to escape a complex multilingualism. Lingala was the language of music, of presidential addresses, of daily life in government and in Kinshasa. But if Lingala was the spoken language of Kinshasa, it made little progress as a written language. French was the written language of the city, as seen in street signs, posters, newspapers and in government documents. French dominated plays and television as well as the press; French was the language of the national anthem and even for the doctrine of authenticity. Zairian researchers found French to be used in vertical relationsihps among people of uneven rank; people of equal rank, no matter how high, tended to speak Zairian languages among themselves. Given these limits, French might have lost its place to another of the leading languages of Zaïre – Lingala, Tshiluba, or Swahili – except that teaching of these languages also suffered from limitations on its growth.

- ↑ Nzuzi (2008), p. 14.

- ↑ Aurélie Fontaine, "Housing: Kinshasa is for the rich”; Africa Report 5 May 2015.

- ↑ "Kinshasa – national capital, Democratic Republic of the Congo". britannica.com.

- ↑ "Plus de 13 000 passagers transportés par train entre Kinshasa et Matadi" (in French). Radio Okapi. 10 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ↑ (in French) L'enfer des chemins de fer urbains kinois, Le Potentiel, 25 July 2005.

- ↑ DRC CONGO: KINSHASHA|Railways Africa Archived 13 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ (in French) La Stib à Kinshasa ?, La Dernière Heure, 24 May 2007.

- ↑

- ↑ Meuser, Philipp; Dalbai, Adil, eds. (1 November 2018). "Sub-Saharan Africa: Architectural Guide". DOM Publishers. Retrieved 17 August 2018 – via Amazon.

- ↑ "CHARTE & MISSION – LeCongolais". Lecongolais.cd. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ↑ "Sister Cities of Ankara". Ankara.bel.tr. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

Bibliography

- Nzuzi, Francis Lelo (2008). Kinshasa: Ville et Environnement. Paris: L'Harmattan, September 2008. ISBN 978-2-296-06080-7.

- Pain, Marc (1984). Kinshasa: la ville et la cité. Paris: Orstom, Institut Français de Recherche Scientifique pour le Développement en Coopération.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kinshasa. |

- Official website of the city of Kinshasa

- Map of the Belgian Congo from 1896 includes a map of Kinshasa

- Slideshow of 21 photos of Kinshasa from 2013 to 2015 on Open Society Foundations website

- Kinshasa: a travers le centre ville, May 2015 – footage from streets of Kinshasa