Ruanda-Urundi

| 1922–1962 | |||||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

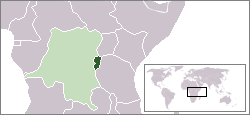

Ruanda-Urundi (dark green) depicted within the Belgian colonial empire (light green), c. 1935. | |||||||||||

| Status | Mandate of Belgium | ||||||||||

| Capital | Usumbura | ||||||||||

| Common languages |

French, Dutch (official) Also: Kirundi, Kinyarwanda | ||||||||||

| Religion |

Roman Catholicism Also: Protestantism, Islam and others | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| April 1916 | |||||||||||

• Creation of mandate | 20 July 1922 | ||||||||||

• Merged with Belgian Congo | August 1925 | ||||||||||

| 1959–62 | |||||||||||

• Independence | 1 July 1962 | ||||||||||

| Currency |

Belgian Congo franc (1916–60) Ruanda-Urundi franc (1960–62) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||

| History of Burundi |

|---|

|

|

Burundi 1962–present

|

|

Current

|

Ruanda-Urundi (French pronunciation: [ʁɥɑ̃da.yʁœ̃di]; in Dutch also Roeanda-Oeroendi [ruˌʋɑndaː ʔuˈrundi]) was a territory in the African Great Lakes region, once part of German East Africa, which was ruled by Belgium between 1916 and 1962. Occupied by the Belgians during the East African Campaign during World War I, the territory was under Belgian military occupation from 1916 to 1922 and later became a Belgian-controlled Class B Mandate under the League of Nations from 1922 to 1945. After the disestablishment of the League and World War II, Ruanda-Urundi became a Trust Territory of the United Nations, still under Belgian control. In 1962, the mandate became independent as the two separate countries of Rwanda and Burundi.

History

Before the Scramble for Africa, the region of Ruanda-Urundi was dominated by two independent kingdoms, Rwanda and Burundi, which were annexed by the German Empire in 1894.[1] The Ruanda-Urundi region formed the westernmost part of the colony of German East Africa, which included modern-day mainland Tanzania.

After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Ruanda-Urundi was the scene of fighting between German and Belgian forces from the Belgian Congo which bordered the region to the west. In April 1916, as part of the East African Campaign, Belgian-Congolese forces invaded Ruanda-Urundi and by September most of the west of German East Africa was under Belgian occupation while forces from the British Empire fought elsewhere in the colony.

Occupation and League of Nations mandate (1919–46)

The Treaty of Versailles divided the German colonial empire among the Allied nations. German East Africa was divided, with the vast majority of the territory, known as Tanganyika, going to the British and the small Kionga Triangle going to Portugal. The western part of the colony, formally referred to as the "Belgian Occupied East African Territories", was allocated to Belgium. This was less than it had originally hoped to receive, since its colonial forces had advanced into Tanganyika during the campaign. The League of Nations officially awarded the mandate over Ruanda-Urundi to Belgium on 20 July 1922. However, the mandate regime was controversial and was not approved by Belgium's parliament until 1924.[2]

The Belgians were far more involved in the territory than the Germans, especially in Ruanda. Despite the mandate rules that the Belgians had to develop the territories and prepare them for independence, the economical policy practised in the Belgian Congo was exported eastwards: the Belgians demanded that the territories earn profits for the motherland and any development must come out of funds gathered in the territory. These funds mostly came from the extensive cultivation of coffee in the region's rich volcanic soils.

To implement their vision, the Belgians used the existing indigenous power structure. This consisted of a largely Tutsi ruling class controlling a mostly Hutu population. The Belgian administrators believed that the Tutsi were superior and deserved power. While before colonization the Hutu had played some role in governance, the Belgians simplified matters by further stratifying the society on racial lines. Hutu anger at the Tutsi domination was largely focused on the Tutsi elite rather than the distant colonial power.[3]

Although promising the League it would promote education, Belgium left the task to subsidised Catholic missions and mostly unsubsidised Protestant missions. As late as 1961, shortly before independence arrived, fewer than 100 natives had been educated beyond secondary level. The policy was one of low-cost paternalism, as explained by Belgium's special representative to the Trusteeship Council: "The real work is to change the African in his essence, to transform his soul, [and] to do that one must love him and enjoy having daily contact with him. He must be cured of his thoughtlessness, he must accustom himself to living in society, he must overcome his inertia."[4]

United Nations trust territory (1946–62)

After the League of Nations was dissolved, the region became a United Nations trust territory in 1946. This included the promise that the Belgians would prepare the areas for independence, but the Belgians felt the area would take many decades to ready for self-rule and wanted the process to take enough time before happening.[5]

Independence came largely as a result of actions elsewhere. In the late 1950s, an independence movement arose in the Belgian Congo, and the Belgians became convinced they could no longer control the territory. Unrest also broke out in Ruanda where the king was deposed. In 1960, Ruanda-Urundi's larger neighbour gained its independence. After two more years of hurried preparations, the trust territory became independent on 1 July 1962, broken up along traditional lines as the independent nations of Rwanda and Burundi. It took two more years before the government of the two became wholly separate.

Colonial governors

.jpg)

Royal Commissioners

- Justin Malfeyt (November 1916 – May 1919)

- Alfred Marzorati (May 1919 – August 1926)

Governors (Deputy Governors-General of the Belgian Congo)

- Alfred Marzorati (August 1926 – February 1929)

- Louis Postiaux (February 1929 – July 1930)

- Charles Voisin (July 1930 – August 1932)

- Eugène Jungers (August 1932 – July 1946)

- Maurice Simon (July 1946 – August 1949)

- Léo Pétillon (August 1949 – January 1952)

- Alfred Claeys-Boúúaert (January 1952 – March 1955)

- Jean-Paul Harroy (March 1955 – January 1962)

See also

- History of Burundi

- History of Rwanda

- List of colonial governors of Ruanda-Urundi

- Archives Africaines (Belgium), which keeps material related to Ruanda-Urundi

References

- ↑ Pike, John. "Rwanda - History". www.globalsecurity.org. GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ William Roger Louis, Ruanda-Urundi 1884-1919 (Oxford U.P., 1963).

- ↑ Peter Langford, "The Rwandan Path to Genocide: The Genesis of the Capacity of the Rwandan Post-colonial State to Organise and Unleash a project of Extermination". Civil Wars Vol. 7 n.3

- ↑ Mary T. Duarte, "Education in Ruanda-Urundi, 1946-61, " Historian (1995) 57#2 pp 275-84

- ↑ "Rwanda profile". BBC Online. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

Further reading

- Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (2003). The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History (English trans. ed.). New York: Zone Books. ISBN 9781890951344.

- Gahama, Joseph (1983). Le Burundi sous administration Belge: la période du mandat, 1919-1939 (2nd rev. ed.). Paris: Karthala. ISBN 9782865370894.

- Louis, William Roger (1963). Ruanda-Urundi 1884-1919. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Newbury, Catharine (1994). The Cohesion of Oppression: Clientship and Ethnicity in Rwanda, 1860-1960. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231062572.

- Rumiya, Jean (1992). Le Rwanda sous le régime du mandat belge, 1916-1931. Paris: Éd. L'Harmattan. ISBN 9782738405401.

- Vijgen, Ingeborg (2005). Tussen mandaat en kolonie: Rwanda, Burundi en het Belgische bestuur in opdracht van de Volkenbond (1916-1932). Leuven: Acco. ISBN 9789033456213.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ruanda-Urundi. |

.svg.png)