Largest artificial non-nuclear explosions

There have been many extremely large explosions, accidental and intentional, caused by modern high explosives, boiling liquid expanding vapour explosions (BLEVEs), older explosives such as gunpowder, volatile petroleum-based fuels such as petrol, and other chemical reactions. This list contains the largest known examples, sorted by date. An unambiguous ranking in order of severity is not possible; a 1994 study by historian Jay White of 130 large explosions suggested that they need to be ranked by an overall effect of power, quantity, radius, loss of life and property destruction, but concluded that such rankings are difficult to assess.[1] The weight of an explosive does not directly correlate with the energy or destructive impact of an explosion, as these can depend upon many other factors such as containment, proximity, purity, preheating, and external oxygenation (in the case of thermobaric weapons, gas leaks and BLEVEs).

In this article, explosion means "the sudden conversion of potential energy (chemical or mechanical) into kinetic energy",[2] as defined by the US National Fire Protection Association, or the common dictionary meaning, "a violent and destructive shattering or blowing apart of something".[3] No distinction is made as to whether it is a deflagration with subsonic propagation or a detonation with supersonic propagation.

Before World War I

- Fall of Antwerp

- On 4 April 1585, during the Spanish siege of Antwerp, a fortified bridge named "Puente Farnesio"[lower-alpha 1] had been built by the Spanish on the River Scheldt. The Dutch launched four large hellburners (explosive fire ships filled with gunpowder and rocks) to destroy the bridge and thereby isolate the city from reinforcement. Three of the hellburners failed to reach the target, but one containing 4 tons of explosive[4] struck the bridge. It did not explode immediately, which gave time for some curious Spaniards to board it. There was then a devastating blast that killed 800 Spaniards on the bridge[5] throwing bodies, rocks and pieces of metal a distance of several kilometres. A small tsunami arose in the river, the ground shook for miles around and a large, dark cloud covered the area. The blast was felt as far as 35 kilometres (22 mi) away in Ghent, where windows vibrated. It has been described as an early weapon of mass destruction.

- Wanggongchang Explosion

- At around nine in the morning of May 30, 1626, a plume of smoke arose from the Wanggongchang Armory in Ming-era Beijing China, followed by an explosion. Almost everything within an area of two square kilometers surrounding the site was destroyed. The estimated death toll was 20,000. About half of Beijing, from Xuanwumen Gate in the South to today's West Chang'an Boulevard in the North, was affected. Guard units stationed as far away as Tongzhou, nearly 40 kilometers away, reported hearing the blast and feeling the earth tremble.[6]

- Great Torrington, Devon

- On 16 February 1646, eighty barrels (5.72 tons) of gunpowder were accidentally ignited by a stray spark during the Battle of Torrington in the English Civil War, destroying the church in which the magazine was located and killing several Royalist guards and a large number of Parliamentarian prisoners who were being held there. The explosion effectively ended the battle, bringing victory to the Parliamentarians. It narrowly missed killing the Parliamentarian commander, Sir Thomas Fairfax. Great damage was caused.

- Delft Explosion

- About 40 tonnes of gunpowder exploded on 12 October 1654, destroying much of the city of Delft in the Netherlands. Over a hundred people were killed and thousands were injured.

- Destruction of the Parthenon

- On 26 September 1687, the Parthenon, hitherto intact, was partially destroyed when an Ottoman ammunition bunker inside was struck by a Venetian mortar. 300 Turkish soldiers were killed in the explosion.

- Brescia Explosion

- In 1769, the Bastion of San Nazaro in Brescia, Italy was struck by lightning. The resulting fire ignited 90 tonnes of gunpowder being stored, and the subsequent explosion destroyed one-sixth of the city and killed 3000 people.

- Siege of Almeida (1810)

- On 26 August 1810, in Almeida, Portugal, during the Peninsular War phase of the Napoleonic Wars, French forces commanded by Marshall André Masséna laid siege to the garrison; the garrison was commanded by British Brigadier General William Cox. A shell made a chance hit on the medieval castle, within the star fortress, which was being used as the powder magazine. It ignited 4000 prepared charges, which in turn ignited 68,000 kg of black powder and 1,000,000 musket cartridges. The ensuing explosion killed 600 defenders and wounded 300. The medieval castle was razed to the ground and sections of the defences were damaged. Unable to reply to the French cannonade without gunpowder, Cox was forced to capitulate the following day with the survivors of the blast and 100 cannon. The French losses during the operation were 58 killed and 320 wounded.

- Fort York magazine explosion

- On 27 April 1813, the magazine of Fort York in Ontario (now Toronto) was fired by retreating British troops during an American invasion. Thirty thousand pounds of gunpowder and thirty thousand cartridges exploded sending debris, cannon and musket balls over the American troops. Thirty eight soldiers, including General Zebulon Pike the American commander, were killed and 222 were wounded.

- Battle of Negro Fort

- On 27 July 1816, the British Royal Marines established a fort on the Apalachicola river known as Negro Fort (later Fort Gadsden). It was occupied by about 330 members of a militia consisting of African American freedmen, Choctaw and Seminole Native Americans, when General Andrew Jackson's navy attacked in a campaign that accelerated the First Seminole War. After five to nine rounds of hot shot, a cannonball entered the fort's powder magazine. The ensuing explosion, which was heard more than 100 miles away,[7] destroyed the entire post which was initially supplied with "three thousand stand of arms, from five to six hundred barrels of powders and a great quantity of fixed ammunition, shot[s], shells".[8] About 270 men, women and children lay dead.[9] General Edmund P. Gaines later said that the "explosion was awful and the scene horrible beyond description." There apparently were no American military casualties.[10]

- Siege of Multan

- On 30 December 1848, in Multan during the Second Anglo-Sikh War, a British mortar shell hit 180 000 kg of gunpowder [200 short tons (180 t)] stored in a mosque, causing an explosion and many casualties.[11]

- Palace of the Grand Master Explosion, in Rhodes

- On 4 April 1856, the Ottomans had stored a large amount of gunpowder in the palace and the adjacent church, which were also full of people. At the time, it was considered that the ringing of bells could prevent the formation of storms. A lightning bolt hit the gunpowder, triggering a blast that killed 4000 people.

- Mobile magazine explosion

- On 25 May 1865, in Mobile, Alabama, in the United States, an ordnance depot (magazine) exploded, killing 300 people. This event occurred just after the end of the American Civil War, during the occupation of the city by victorious Federal troops.

- Flood Rock explosion

- On 10 October 1885 in New York City, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers detonated 300,000 pounds (135 t) of explosives on Flood Rock, annihilating the island, in order to clear the Hell Gate for the benefit of East River shipping traffic.[12] The explosion sent a geyser of water 250 feet in the air;[13] the blast was felt as far away as Princeton, New Jersey.[12] The explosion has been described as "the largest planned explosion before testing began for the atomic bomb",[13] though the detonation at the Battle of Messines was larger. Rubble from the detonation was used in 1890 to fill the gap between Great Mill Rock and Little Mill Rock, merging the two into a single island, Mill Rock.[12]

- Explosion of steam ship Cabo Machichaco

- On 3 November 1893, in Santander, Spain, the steam ship Cabo Machichaco caught fire when she was docked. The ship was loaded with sulphuric acid and 51 tons of dynamite from Galdácano, Basque Country, but authorities were unaware of this. Firefighters and crewmen from other ships boarded the Cabo Machichaco to help fight the fire, while local dignitaries and a large crowd of people watched from the shore. At 5 pm, a huge explosion destroyed nearby buildings and created a huge wave that washed over the seafront. Pieces of iron and rubbish were thrown as far as Peñacastillo, 8 km away, where a person was killed by the falling debris. A total of 590 people were killed, while an uncertain number, estimated from 500 to 2000, were injured.[14][15]

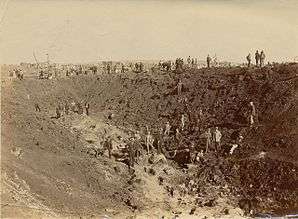

- Braamfontein explosion

- On 19 February 1896, an explosives train at Braamfontein station in Johannesburg, loaded with between 56 and 60 tons of blasting gelatine destined for the burgeoning gold mines of the Witwatersrand and having been standing for three and a half days in searing heat, was struck by a shunting train. The load exploded, leaving a crater in the Braamfontein rail yard 60 metres (200 ft) long, 50 metres (160 ft) wide and 8 metres (26 ft) deep. The explosion was heard up to 200 kilometres (120 mi) away. 75 people were killed, and more than 200 injured. Surrounding suburbs were destroyed, and roughly 3000 people lost their homes. Almost every window in Johannesburg was broken.[16]

- DuPont Powder Mill explosion, Fontanet, Indiana

- On 15 October 1907, approximately 40,000 kegs of powder exploded in Fontanet, Indiana, killing between 50 and 80 people, and destroying the town. The sound of the explosion was heard over 200 miles (320 km) away, with damage occurring to buildings 25 miles (40 km) away.[17]

- Alum Chine

- Alum Chine was a Welsh freighter (out of Cardiff) carrying 343 tons of dynamite for use during construction of the Panama Canal. She was anchored off Hawkins Point, near the entrance to Baltimore Harbor in Baltimore, Maryland. She exploded on 7 March 1913, killing over 30, injuring about 60, and destroying a tugboat and two barges. Most accounts describe two distinct explosions.[18]

World War I

- HMS Princess Irene at Sheerness

- On 27 May 1915 the converted minelayer HMS Princess Irene suffered a blast. Wreckage was thrown up to 20 miles while a collier ship half a mile away had its crane blown off and a crew member was killed by a fragment weighing 70 pounds. A child ashore was killed by another fragment. A case of butter was found six miles away. A total of 352 people were killed but one crew member survived, with severe burns. The ship had been loaded with 300 sea mines containing more than 150 tons of high explosive. An inquiry blamed faulty priming, possibly by untrained personnel.

- Faversham explosion

- On 2 April 1916, an explosion ripped through the gunpowder mill at Uplees, near Faversham, Kent, when 200 tons of TNT ignited. 105 people died in the explosion. The munitions factory was next to the Thames estuary, and the explosion was heard across the estuary as far away as Norwich, Great Yarmouth, and Southend-on-Sea, where domestic windows were blown out and two large plate-glass shop windows shattered.

- Battle of Jutland

- On 31 May 1916, three British battlecruisers were destroyed by cordite deflagrations initiated by armour-piercing shells fired by the German High Seas Fleet. At 16:02 HMS Indefatigable was cut in two by deflagration of the forward magazine and sank immediately with all but two of her crew of 1019. German eyewitness reports and the testimony of modern divers suggest all her magazines exploded. The wreck is now a debris field. At 16:25 HMS Queen Mary was cut in two by detonation of the forward magazine and sank with all but 21 of her crew of 1283. As the rear section capsized it also exploded. At 18:30 HMS Invincible was cut in two by detonation of the midships magazine and sank in 90 seconds with all but six of her crew. 1026 men died, including Rear Admiral Hood. An armoured cruiser, HMS Defence, was a fourth ship to suffer an explosive deflagration at Jutland with at least 893 men killed. The rear magazine was seen to detonate followed by more explosions as the cordite flash travelled along an ammunition passage beneath her broadside guns. Eye witness reports suggest that HMS Black Prince may also have suffered an explosion as she was lost during the night action with all hands — 857 men. British reports say she was seen to blow up. German reports speak of the ship being overwhelmed at close range and sinking. Finally, during the confused night actions in the early hours of 1 June, the German pre-dreadnought SMS Pommern was hit by one, or possibly two, torpedoes from the British destroyer HMS Onslaught, which detonated one of Pommern's 17-centimetre (6.7 in) gun magazines. The resulting explosion broke the ship in half and killed the entire crew of 839 men.

- Mines on the first day of the Somme

- On the morning of 1 July 1916, a series of 19 mines of varying sizes was blown to start the Battle of the Somme. The explosions constituted what was then the loudest human-made sound in history, and could be heard in London. The largest single charge was the Lochnagar mine south of La Boisselle with 60,000 lb (27 t) of ammonal explosive. The mine created a crater 300 ft (90 m) across and 90 ft (30 m) deep, with a lip 15 ft (5 m) high. The crater is known as Lochnagar Crater after the trench from where the main tunnel was started.

- Black Tom explosion

- On 30 July 1916, sabotage by German agents caused 1,000 short tons (910 t) of explosives bound for Europe, along with another 50 short tons (45 t) on the Johnson Barge No. 17, to explode in Jersey City, New Jersey, a major dock serving New York. There were few deaths, but about 100 injuries. Damage included buildings on Ellis Island, parts of the Statue of Liberty, and much of Jersey City.

- Silvertown explosion

- On 19 January 1917, parts of Silvertown in East London were devastated by a TNT explosion at the Brunner-Mond munitions factory. 73 people died and hundreds were injured. The blast was felt across London and Essex and was heard over 100 mi (160 km) away, with the resulting fires visible for 30 mi (48 km).

- Quickborn Explosion

- On 10 February 1917 a chain reaction in an ammunition plant "Explosivstoffwerk Thorn" in Quickborn-Heide (northern Germany) killed at least 115 people (some sources say over 200), mostly young female workers.[19][20]

- Plzeň explosion

- Škoda Works in Bolevec, Plzeň, was the biggest ammunition plant in Austria-Hungary. A series of explosions on 25 May 1917 killed 300 workers.[21] This event inspired Karel Čapek to write the novel Krakatit (1922).

- Mines in the Battle of Messines

- On 7 June 1917, a series of large British mines, containing a total of over 455 tons of ammonal explosive, was detonated beneath German lines on the Messines-Wytschaete ridge. The explosions created 19 large craters, killed about 10,000 German soldiers, and were heard as far away as London and Dublin. While determining the power of explosions is difficult, this was probably the largest planned explosion in history until the 1945 Trinity atomic weapon test, and the largest non-nuclear planned explosion until the 1947 British Heligoland detonation (below). The Messines mines detonation killed more people than any other non-nuclear man-made explosion in history.

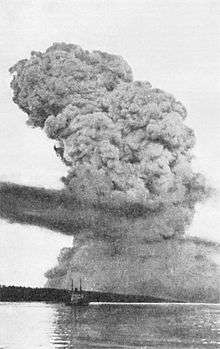

- Halifax Explosion

- On 6 December 1917 the SS Imo and the SS Mont-Blanc collided in the harbour of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Mont-Blanc carried 2653 tonnes of various explosives, mostly picric acid. After the collision the ship caught fire, drifted into town, and exploded. 1,950 people were killed and much of Halifax was destroyed. An evaluation of the explosion's force puts it at 2.9 kilotons of TNT (12 TJ).[22] Halifax historian Jay White in 1994 concluded "Halifax Harbour remains unchallenged in overall magnitude as long as five criteria are considered together: number of casualties, force of blast, radius of devastation, quantity of explosive material, and total value of property destroyed."

- Chilwell Munitions Factory Explosion

- On July 1, 1918, the National Shell Filling Factory No 6 (Chilwell, near Nottingham, England) was partly destroyed when 8 tons of TNT exploded in the dry mix part of the factory. Approximately 140 workers - mainly young women, known as the 'Chilwell Canaries' because contact with TNT turned their skin yellow - were killed, though the true number has never been satisfactorily established. An unknown number of people were injured, though estimates place the figure at around 250. Because of the sensitivity of the subject, reports of the explosion were censored until after the Armistice. The cause of the explosion was never officially established, though present-day authorities on explosives consider it was down to a combination of factors: an exceptionally hot day, high production demands and lax safety precautions.

- Split Rock explosion

- On 2 July 1918 a munitions factory near Syracuse, New York, exploded after a mixing motor in the main TNT building overheated. The fire rapidly spread through the wooden structure of the main factory. Approximately 1–3 tons of TNT were involved in the blast, which levelled the structure and killed 50 workers (conflicting reports mention 52 deaths).

- T. A. Gillespie Company Shell Loading Plant explosion, or Morgan Depot Explosion

- On 4 October 1918 an ammunition plant — operated by the T. A. Gillespie Company and located in the Morgan area of Sayreville in Middlesex County, New Jersey — exploded and triggered a fire. The subsequent series of explosions continued for three days. The facility, said to be one of the largest in the world at the time, was destroyed, along with more than 300 buildings forcing reconstruction of South Amboy and Sayreville. Over 100 people died in this accident.[23] Over a three-day period, a total of 12,000,000 pounds (5,400 t) of explosives were destroyed.[24]

Interwar period

- Oppau explosion

- On 21 September 1921 a BASF silo filled with 4500 tonnes of fertilizer exploded, killing around 560, largely destroying Oppau, Germany, and causing damage more than 30 km away.

- Nixon New Jersey Explosion

- The 1924 Nixon Nitration Works disaster was an explosion and fire that claimed many lives and destroyed several square miles of New Jersey factories. On 1 March 1924, an explosion destroyed a building in Nixon, New Jersey used for processing ammonium nitrate. The explosion touched off fires in surrounding buildings in the Nixon Nitration Works that contained other highly flammable materials. The disaster killed twenty and destroyed forty buildings.

- Leeudoringstad explosion

- On 17 July 1932, a train carrying 320 to 330 tons of dynamite from the De Beers factory at Somerset West to the Witwatersrand exploded and flattened the small town of Leeudoringstad in South Africa. Five people were killed and 11 injured in the sparsely-populated area.

- Neunkirchen gas detonation

- On February 10, 1933, a gas storage in Neunkirchen/Saar, Germany detonated during maintenance work. The detonation could be heard at 124 miles distance. The death toll was 68, and 160 were injured.

- Hirakata ammunition dump explosion

- On 1 March 1939, Warehouse No. 15 of the Japanese Imperial Army's Kinya ammunition dump in Hirakata, Osaka Prefecture, Japan, suffered a catastrophic explosion, the sound of which could be heard throughout the Keihan area. Additional explosions followed over the next few days as the depot burned, for a total of 29 explosions by 3 March. Japanese officials reported that 94 people died, 604 were injured, and 821 houses were damaged, with 4,425 households in all suffering the effects of the explosions.[25][26]

World War II

- Pluton

- On 13 September 1939 the French cruiser Pluton exploded and sank while offloading naval mines in Casablanca, in French Morocco. The explosion killed 186 men, destroyed three nearby armed trawlers, and damaged nine more.

- SS Clan Fraser

- On 6 April 1941 the SS Clan Fraser was moored in Piraeus harbour, Greece. Three German bombs struck her igniting 350 tonnes of TNT, a nearby barge carried a further 100 tonnes which also detonated. British navy ships HMS Ajax and HMS Calcutta, attempted to tow her out of harbour and succeeded in getting beyond the breakwater, after the tow line had broken 3 times. She then exploded levelling large areas of the port. This was witnessed by post-war author Roald Dahl, who was piloting a fighter plane.

- HMS Hood

- On 24 May 1941 the battle cruiser sank in three minutes after the stern magazine detonated during the Battle of the Denmark Strait. The wreck has been located in three pieces, suggesting additional detonation of a forward magazine. There were only three survivors from the crew of 1418.

- HMS Barham

- On 25 November 1941 HMS Barham sunk by U-331; 862 crew lost. This incident was captured on film by a Pathe News cameraman on board the nearby HMS Valiant.

- Smederevo Fortress

- During World War II, German invading forces in Serbia used Smederevo Fortress for ammunition storage. On 5 June 1941 it exploded,[27] blasting through the entirety of Smederevo and reaching settlements as far as 10 km away. Much of the southern wall of the fortress was destroyed, the nearby railway station, packed with people, was blown away, and most of the buildings in the city were turned into debris. Around 2,500 people died in the explosion, and every other inhabitant was injured[28] (approximately 5,500).

- SS Surrey

- On the night of 10 June 1942, U-68 torpedoed the 8600-ton British freighter Surrey in the Caribbean Sea. Five thousand tons of dynamite in the cargo detonated after the ship sank. The shock wave lifted U-68 out of the water as if she had suffered a torpedo hit, and both diesel engines and the gyrocompass were disabled.[29]

- Convoy SC 107

- On the night of 3 November 1942, torpedoes detonated the ammunition cargo of the 6690-ton British freighter Hatimura. Both the freighter and attacking submarine U-132 were destroyed by the explosion.[30]

- Naples Caterina Costa explosion

- On 28 March 1943 in the port of Naples a fire broke out on Caterina Costa, an 8060-ton motor ship with arms and supplies (1000 tons of gas, 900 tons of explosives, tanks and others); the fire became uncontrollable, causing a devastating explosion. A large number of buildings around were destroyed or badly damaged. Some ships nearby caught fire and sank while hot parts of the ship and tanks were thrown at great distance. More than 600 dead and over 3000 wounded.

- Bombay Docks explosion

- On 14 April 1944 the SS Fort Stikine, carrying around 1,400 long tons (1,400 t) of explosives (among other goods), caught fire and exploded, killing around 800 people.

- Bergen Harbour explosion

- On 20 April 1944 the Dutch steam trawler Voorbode, loaded with 124,000 kg of explosives, caught fire and exploded at the quay in the centre of Bergen. The air pressure from the explosion and the tsunami that followed flattened whole neighbourhoods near the harbour. Fires broke out in the aftermath, leaving 5000 people homeless. 160 people were killed and 5000 wounded.

- SS Paul Hamilton

- On 20 April 1944 Liberty ship SS Paul Hamilton was attacked 30 miles off Cape Bengut near Algiers by Luftwaffe Bombers. The ship and 580 personnel aboard were destroyed within 30 seconds when the cargo of bombs and explosives detonated.

- West Loch disaster

- On 21 May 1944 an ammunition handling accident in Pearl Harbor destroyed six LSTs and 3 LCTs. Four more LSTs, ten tugs, and a net tender were damaged. Eleven buildings were destroyed ashore and nine more damaged. Nearly 400 military personnel were killed.

- Port Chicago disaster

- On 17 July 1944 in Port Chicago, California, the SS E. A. Bryan exploded while loading ammunition bound for the Pacific, with an estimated 4,606 short tons (4,178 t) of high explosive, incendiary bombs, depth charges, and other ammunition. Another 429 short tons (389 t) waiting on nearby rail cars also exploded. The total explosive content is described as between 1600[31] and 2,136[32] tons of TNT. 320 were killed instantly, another 390 wounded. Most of the killed and wounded were African American enlisted men. Following the explosion, 258 fellow sailors refused to load ordnance; 50 of these, called the "Port Chicago 50", were convicted of mutiny even though they were willing to carry out any order that did not involve loading ordnance under unsafe conditions.[33]

_explodes_at_Seeadler_Harbor_on_10_November_1944.jpg)

- Cleveland East Ohio Gas Explosion

- On 20 October 1944, a liquefied natural gas storage tank in Cleveland, Ohio, split and leaked its contents, which spread, caught fire, and exploded. A half hour later, another tank exploded as well. The explosions destroyed 1 square mile (2.6 km2), killed 130, and left 600 homeless.

- USS Mount Hood

- On 10 November 1944 the ammunition ship exploded in Seeadler Harbor at Manus Island in Papua New Guinea, with an estimated 3800 tons of ordnance material on board. Mushrooming smoke rose to 7000 feet (2000 m), obscuring the ship and the surrounding area for a radius of approximately 500 yards (500 m). Mount Hood's former position was revealed by a trench in the ocean floor 1000 feet (300 m) long, 200 feet (60 m) wide, and 30 to 40 feet (10 to 12 m) deep. The largest remaining piece of the hull was found in the trench and measured 16 by 10 feet (5 by 3 m). All 296 men aboard the ship were killed. The USS Mindanao was 350 yards (320 m) away and suffered extensive damage, with 23 crew killed, and 174 injured. Several other nearby ships were also damaged or destroyed. Altogether 372 were killed and 371 injured in the blast.

- RAF Fauld Explosion

- On 27 November 1944 the RAF Ammunition Depot at Fauld, Staffordshire, became the site of the largest explosion in the UK, when 3,700 tonnes of bombs stored in underground bunkers covering 17,000 square metres exploded en masse. The explosion was caused by bombs being taken out of store, primed for use, and replaced with the detonators still installed when unused. The crater was 30 metres deep and covered 5 hectares. The death toll was approximately 78, including RAF, six Italian POWs, civilian employees, and local people. In the similar Port Chicago disaster (above), about half the weight of bombs was high explosive. If the same is true of the Fauld Explosion, it would have been equivalent to about 2 kilotons of TNT.

- Japanese aircraft carrier Unryu

- On 19 December 1944 the carrier disintegrated when torpedoes fired by USS Redfish detonated the forward magazine.

- Japanese battleship Yamato

- On 7 April 1945, after six hours of battle, Yamato's magazine exploded as she sank, resulting in a mushroom cloud rising six kilometres above the wreck, and which could be seen from Kyushu, 160 kilometres away. 2055 crewmen were killed.

- Trinity calibration test

- On 7 May 1945, 100 tons of TNT was stacked on a wooden tower and exploded to test the instrumentation prior to the test of the first atomic bomb.

1945-2000

- Futamata Tunnel Explosion

- On 12 November 1945, When the occupation troops were trying to dispose of 530 tons of ammunition, there was an explosion in a tunnel in Soeda, Fukuoka Prefecture, Kyushu Island. According to a confirmed official report, 147 local residents were killed and 149 people injured.[34]

- Texas City Disaster

- On 16 April 1947, the SS Grandcamp, loaded with 8,500 short tons (7,700 t) of ammonium nitrate, exploded in port at Texas City, Texas. 581 died, over 5,000 injured. Using standard chemical data for decomposition of ammonium nitrate makes this equivalent to 2.7 kilotons of TNT exploding.[lower-alpha 2] The US Army rates the relative effectiveness factor of ammonium nitrate, compared to TNT, as 0.42.[35] This conversion factor makes the blast equivalent to (0.42)7,770 tons, or 3.2 kilotons of TNT, with the discrepancy between the total energy and relative effectiveness value of the explosive power being due to direct comparisons between high explosives not being as simplistic as comparing total internal energy of each high explosive.

- This is generally considered the worst industrial accident in United States history.

- Heligoland "British Bang"

- On 18 April 1947 British engineers attempted to destroy the entire North Sea island of Heligoland in what became known as the "British Bang". The island had been fortified during the war with a submarine base and airfield[36][37] Roughly 4000 tons[38][39] of surplus World War II ammunition were placed in various locations around the island and set off. The island survived, although the extensive fortifications were destroyed. According to Willmore,[39] the energy released was 1.3×1020 erg (1.3×1013 J), or about 3.2 kilotons of TNT equivalent. The blast is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records under largest single explosive detonation, although Minor Scale in 1985 was larger (see below).

- Ocean Liberty in Brest, France

- On 28 July 1947, the Norwegian cargo ship Ocean Liberty exploded in the French port of Brest. The cargo consisted of approximately 3300 tonnes of ammonium nitrate in addition to paraffin and petrol. The explosion killed 22 people, hundreds were injured, 4000–5000 buildings were damaged.[40]

- Cádiz Explosion

- On 18 August 1947, a naval ammunition warehouse containing mostly mines and torpedoes exploded in Cádiz, in southern Spain, for unknown reasons. The explosion of approximately 200 tons of TNT destroyed a large portion of the city. Officially, the explosion killed 150 people; the real death toll is suspected to be higher.

- Explosion at Prüm

- On 15 July 1949 in the German town of Prüm, an underground bunker inside the hill of Kalvarienberg and used previously by the German army to store ammunition, but now filled with French army munitions, caught fire. After a mostly successful evacuation, the 500 tonnes of ammunition in the bunker exploded and destroyed large parts of the town. 12 people died and 15 were severely injured.[41]

- Guayuleras explosion

- On 23 September 1955 in the Mexican city of Gómez Palacio, Durango, two trucks loaded with 15 tons of dynamite exploded when they apparently collided with a passenger train, causing many deaths.[42]

- Cali explosion, Colombia

- On 7 August 1956 seven trucks from the Colombian army, carrying more than 40 tons of dynamite, exploded. The explosion killed more than 1000 people, and left a crater 25 metres (70 ft) deep and 60 metres (200 ft) in diameter.[43][44]

- Ripple Rock, British Columbia, Canada

- On 5 April 1958 an underwater mountain was levelled by the explosion of 1375 tonnes of Nitramex2H, an ammonium nitrate-based explosive. This was one of the largest non-nuclear planned explosions on record, and the subject of the first CBC live broadcast coast-to-coast.

- Operation Blowdown

- On 18 July 1963, a test-blast of 50 tons of TNT in the Iron Range area of Queensland, Australia, tested the effects of nuclear weapons on tropical rainforest, military targets and ability of troops to transit through the resulting debris field.[45]

- CHASE 2, off New Jersey

- On 17 September 1964, the offshore disposal of the ship Village, containing 7,348-short-ton (6,666 t) of obsolete munitions, caused unexpected detonations 5 minutes after sinking. The detonations were detected on seismic instruments around the world; the incident encouraged intentional detonation of subsequent disposal operations to determine detectability of underwater nuclear testing.[46]

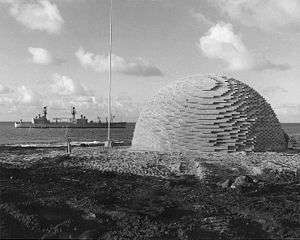

- Operation Sailor Hat, off Kaho'olawe Island, Hawaii

- A series of tests was performed in 1965, using conventional explosives to simulate the shock effects of nuclear blasts on naval vessels. Each test saw the detonation of a 500-short-ton (450 t) mass of high explosives.

- CHASE 3 and 4, off New Jersey

- On 14 July 1965, Coastal Mariner was loaded with 4,040-short-ton (3,670 t) of obsolete munitions containing 512-short-ton (464 t) of high explosives. The cargo was detonated at a depth of 1,000 feet (300 m) and created a 600-foot (200 m) water spout, but was not deep enough to be recorded on seismic instruments. On 16 September 1965, Santiago Iglesias was similarly detonated with 8,715-short-ton (7,906 t) of obsolete munitions.[46]

- Medeo Dam, near Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan

- On 21 October 1966 a mud flow protection dam was created by a series of four preliminary explosions of 1,800 tonnes total and a final explosion of 3,600 tonnes of ammonium nitrate-based explosive. On 14 April 1967 the dam was reinforced by an explosion of 3,900 tonnes of ammonium nitrate-based explosive.

- CHASE 5, off Puget Sound

- On 23 May 1966, Izaac Van Zandt was loaded with 8,000-short-ton (7,300 t) of obsolete munitions containing 400-short-ton (360 t) of high explosives. The cargo was detonated at a depth of 4,000 feet (1.2 km).[46]

- CHASE 6, off New Jersey

- On 28 July 1966, Horace Greeley was loaded with obsolete munitions and detonated at a depth of 4000 feet (1.2 km).[46]

- N1 launch explosion

- On 3 July 1969, an N1 rocket in the Soviet Union exploded on the launch pad, after a turbopump exploded in one of the engines. The entire rocket contained about 680,000 kg (680 t) of kerosene and 1,780,000 kg (1,780 t) of liquid oxygen.[47] Using a standard energy release of 43 MJ/kg of kerosene gives about 29 TJ for the energy of the explosion (about 6.93 kt TNT equivalent). Investigators later determined that up to 85% of the fuel in the rocket did not detonate, meaning that the blast yield was likely no more than 1kt TNT equivalent.[48] On the other hand, windows were blow out at Site 2, 6 km away, and others shattered at up to 40 km distant.[48] This is consistent with a much larger explosion - a 1kt blast would only be expected to break windows out to a 2 km radius.[49]

- Comparing explosions of initially unmixed fuels is difficult (being part detonation and part deflagration).

- Old Reliable Mine Blast

- On March 9, 1972, approximately 2,000 tons (4 million pounds) of explosive were detonated inside three levels of tunnels in the Old Reliable Mine near Mammoth, Arizona.[50] The blast was an experimental attempt to break up the ore body so that metals (primarily copper) could be extracted using sulfuric acid in a heap-leach process. The benefits of increased production were short-lived while the costs of managing acid mine drainage due to the sulfide ore body being exposed to oxygen continue to the present day.

- Flixborough disaster

- On 1 June 1974, a pipe failure at the Nypro chemical plant in Flixborough, England, caused a large release of flammable cyclohexane vapour. This ignited and the resulting fuel-air explosion destroyed the plant, killing 28 people and injuring 36 more. Beyond the plant 1,821 houses and 167 shops and factories had suffered to a greater or lesser degree.[51] Fires burnt for 16 days. The explosion occurred at a weekend otherwise the casualties would have been much heavier. This explosion caused a significant strengthening of safety regulations for chemical plants in the United Kingdom.

- Iri Station Explosion

- On 11 November 1977, a freight train carrying 40 tons of dynamite from Gwangju suddenly exploded at Iri station (present-day Iksan), Jeollabuk-do province, South Korea. The cause of the explosion was accidental ignition by an intoxicated guard. 59 people lost their lives, and 185 others seriously wounded; altogether, over 1300 people were injured or killed.

- Los Alfaques disaster

- On 11 July 1978, an overloaded tanker truck carrying 23 tons of liquefied propylene crashed and ruptured in Spain, emitting a white cloud of ground-hugging fumes which spread into a nearby campground and discothèque before reaching an ignition source and exploding. 217 people were killed and 200 more severely burned.

- Murdock BLEVEs

- In 1983 near Murdock, Illinois, at least two tanker cars of a burning derailed train exploded into BLEVEs; one of them was thrown nearly three-quarters of a mile.[52]

- Benton fireworks disaster

- On 27 May 1983 an explosion at an illegal fireworks factory near Benton, Tennessee killed eleven, injured one, and caused damage within a radius of several miles. The blast created a mushroom cloud 600 to 800 feet tall and was heard as far as fifteen miles away.[53]

- 1983 Newark explosion

- On 7 January 1983 an explosion of the Texaco oil tank farm was felt for 100–130 miles from Newark, New Jersey claiming 1 life and injuring 22–24 people.

- Minor Scale and Misty Picture

- Many very large detonations have been carried out in order to simulate the effects of nuclear weapons on vehicles and other military material.[54] The largest publicly known test was conducted by the United States Defense Nuclear Agency (now part of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency) on 27 June 1985 at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. This test, called Minor Scale, used 4744 short tons of ANFO, with a yield of about 4 kt.[55] Misty Picture was another similar test a few years later, slightly smaller at 4,685 short tons or 4,250 t.

- PEPCON Disaster

- On 4 May 1988 about 4,250 short tons (3,860 metric tons) of ammonium perchlorate (NH4ClO4) caught fire and set off explosions near Henderson, Nevada. A 16-inch (41 cm) natural gas pipeline ruptured under the stored ammonium perchlorate and added fuel to the later, larger explosions. There were seven detonations in total, the largest being the last. Two people were killed and hundreds injured. The largest explosion was estimated to be equivalent to 1 kiloton of TNT (4.2 TJ).[56][57] The accident was caught on video by a broadcast engineer servicing a transmitter on a nearby mountaintop.[58]

- Arzamas train disaster

- Arzamas explosion, known also as Arzamas train disaster occurred on 4 June 1988, when three goods wagons transporting hexogen to Kazakhstan exploded on a railway crossing in Arzamas, Gorky Oblast, USSR (now Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, Russia). Explosion of 118 tons of hexogen made a 26-metre deep crater (85 ft), and caused major damage, killing 91 people and injuring 1500. 151 buildings were destroyed.

- Ufa train disaster

- On 4 June 1989, a gas explosion destroyed two trains (37 cars and two locomotives) in the Soviet Union. At least 575 people died and more than 800 were injured.[59]

- Intelsat 708 Long March 3B launch failure

- On 14 February 1996, a Chinese rocket veered severely off course immediately after clearing the launch tower, then crashed into a nearby city and exploded. Following the disaster, foreign media were kept in a bunker for five hours while, some alleged, the Chinese military attempted to "clean up" the damage. Officials later blamed the failure on an "unexpected gust of wind" although video shows this is not the case. Xinhua News Agency initially reported 6 deaths and 57 injuries.[60][61]

- Enschede fireworks disaster

- On 13 May 2000, 177 tonnes of fireworks exploded in Enschede, in the Netherlands, in which 23 people were killed and 947 were injured.[62] The first explosion had the order of 800 kg TNT equivalence; the final explosion was in the range of 4,000–5,000 kg TNT.[63]

2001–present

- AZF chemical factory

- On 21 September 2001, an explosion occurred at a fertilizer factory in Toulouse, France. The disaster caused 31 deaths, 2,500 seriously wounded, and 8,000 light injuries. The blast (estimated yield of 20–40 tons of TNT, comparable in scale to the military test Operation Blowdown) was heard 80 km away (50 miles) and registered 3.4 on the Richter magnitude scale. It damaged about 30,000 buildings over about two-thirds of the city, for an estimated total cost of about €2 billion.[64]

- Ryongchon disaster

- A train exploded in North Korea on 22 April 2004. According to official figures, 54 people were killed and 1249 were injured.[65]

- Seest fireworks disaster

- On 3 November 2004, about 284 tonnes of fireworks exploded in Kolding, in Denmark. One firefighter was killed, and a mass evacuation of 2,000 people saved many lives. The cost of the damage was estimated at €100 million.

- Texas City Refinery explosion

- On 23 March 2005, there was a hydrocarbon leak due to incorrect operations during a start up which caused a vapour cloud explosion when ignited by a running vehicle engine. There were 15 deaths and more than 170 injured.

- 2005 Hertfordshire Oil Storage Terminal fire

- On 11 December 2005, there was a series of major explosions at the 60,000,000 imp gal (270,000,000 L) capacity Buncefield oil depot near Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, England. The explosions were heard over 100 mi (160 km) away, as far as the Netherlands and France, and the resulting flames were visible for many miles around the depot. A smoke cloud covered Hemel Hempstead and nearby parts of west Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire. There were no fatalities, but there were around 43 injuries (2 serious). The British Geological Survey estimated the equivalent yield of the explosion as 29.5 tonnes TNT.[66]

- Sea Launch failure

- On 30 January 2007, a Sea Launch Zenit-3SL space rocket exploded on takeoff. The explosion consumed the roughly 400,000 kg (400 t) of kerosene and liquid oxygen on board. This rocket was launched from an uncrewed ship in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, so there were no casualties; the launch platform was damaged and the NSS-8 satellite was destroyed.

- 2007 Maputo arms depot explosion

- On 22 March 2007, a series of explosions over 2.5 hours rocked the Mozambican capital of Maputo. The incident was blamed on high temperatures. Officials confirmed 93 fatalities and more than 300 injuries.[67][68]

- 2009 Cataño oil refinery fire

- On the morning of 23 October 2009, there was a major explosion at the petrol tanks at the Caribbean Petroleum Corporation oil refinery and oil depot in Bayamón, Puerto Rico.[69] The explosion was seen and heard from 50 miles (80 km) away and left a smoke plume with tops as high as 30,000 feet (9 km) It caused a 3.0 earthquake and blew glass out of windows around the city. The resulting fire was extinguished on 25 October.

- Ulyanovsk arms depot explosion

- On 13 and 23 November 2009, 120 tons of Soviet-era artillery shells blew up in two separate sets of explosions at the 31st Arsenal of the Caspian Sea Flotilla's ammunition depot near Ulyanovsk, killing ten.[70][71]

- Evangelos Florakis Naval Base explosion

- At around 5:45 am local time on 11 July 2011, a fire at a munitions dump at Evangelos Florakis Naval Base near Zygi, Cyprus, caused the explosion of 98 cargo containers holding various types of munitions. The naval base was destroyed, as was Cyprus's biggest power plant, the "Vassilikos" power plant 500 m away. The explosion also caused 13 deaths and injuries to over 60. Injuries were reported up to 5 km away and damaged houses were reported as far as 10 km away.[72][73] Seismometers at the Mediterranean region recorded the explosion as a M3.0 seismic event.[74]

- Cosmo Oil Refinery Fire

- The Cosmo Oil Company's refinery in Japan's Ichihara, Chiba Prefecture, caught fire during the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake. As it burned, several pressurised liquefied propane gas storage tanks exploded into fireballs, one in particular being the largest fireball over Japan since the bombing of Nagasaki.

- Donguz Ammunition depot explosion

- On 8–9 October 2012, a Russian ammunition depot, at the Donguz test site, containing 4,000 tons of shells exploded some 40 kilometres from Orenburg in Central Russia.[75][76]

- Texas fertilizer plant explosion

- On 17 April 2013, a fire culminating in an explosion shortly before 8 p.m. CDT (00:50 UTC, 18 April) destroyed the West Fertilizer Company plant in West, Texas, located 18 miles (29 km) north of Waco, Texas.[77][78] The blast killed 15 people, injured over 160, and destroyed over 150 buildings. The United States Geological Survey recorded the explosion as a 2.1-magnitude earthquake, the equivalent of 7.5 – 10 tons of TNT.[79][80][81]

- Lac-Mégantic rail disaster

- On 6 July 2013, a train of 73 tank cars of light crude oil ran away down a slight incline, after being left unattended for the night, when the air brakes failed after the locomotive engines were shut down following a small fire. It derailed twelve kilometres away in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, Canada, igniting the Bakken light crude oil from 44 DOT-111 oil cars. Approximately 3–4 minutes after the initial blast, there was a second explosion from 12 oil cars. A series of smaller blasts followed into the early morning hours, igniting the oil of a total 73 oil cars. The disaster killed 42 people with five more missing presumed dead.[82]

- 2015 Tianjin explosions

- On 12 August 2015, at 23:30, two explosions occurred in the Chinese port Tianjin at a warehouse operated by Ruihai Logistics. The China Earthquake Networks Center reported that the first blast generated shock-waves equivalent to 3 tonnes TNT, the 2nd 21 tonnes TNT.[83] 173 people were killed, and 8 remain missing.[84]

- 2016 San Pablito Market fireworks explosion

- On 20 December 2016, a fireworks explosion occurred at the San Pablito Market in the city of Tultepec, north of Mexico City. At least 42 people were killed, and dozens injured.

Comparison with large conventional military ordnance

The most powerful non-nuclear weapons ever designed are the United States' MOAB (standing for Massive Ordnance Air Blast, also nicknamed Mother Of All Bombs, tested in 2003 and used on April 13, 2017, In Achen Province, Afghanistan) and the Russian Father of All Bombs (tested in 2007). The MOAB contains 18,700 lb (8.5 t) of the H6 explosive, which is 1.35 times as powerful as TNT, giving the bomb an approximate yield of 11 t TNT. It would require about 250 MOAB blasts to equal the Halifax explosion (2.9 kt).

Conventional explosions for nuclear testing

Some large conventional explosions have been conducted for nuclear testing purposes. Some of the larger ones are listed below.[85]

| Event | Explosive used | Amount of explosive | Where | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trinity (100-ton Test on tower) | TNT | 100 short tons (91 t)[86][87] | White Sands Proving Grounds | 7 May 1945 |

| – | TNT | 100 short tons (91 t) | Suffield Experimental Station, Alberta, Canada | 3 August 1961 |

| Blowdown | TNT | 50 short tons (45 t) | Lockhart River, Queensland | 18 July 1963 |

| Snowball | TNT | 500 short tons (450 t) | Suffield Experimental Station, Alberta, Canada | 17 July 1964 |

| Sailor Hat | TNT | 3 tests × 500 short tons (450 t) | Kahoolawe, Hawaii | 1965 |

| Distant Plain | Propane or methane | 20 short tons (18 t) | Suffield Experimental Station, Alberta, Canada | 1966–1967 (6 tests) |

| Prairie Flat | TNT | 500 short tons (450 t) | Defence Research Establishment Suffield, Alberta, Canada | 1968 |

| Dial Pack | TNT | 500 short tons (450 t) | Defence Research Establishment Suffield, Alberta, Canada | 23 July 1970 |

| Mixed Company 3 | TNT | 500 short tons (450 t) | Colorado | 20 November 1972 |

| Dice Throw | ANFO | 620 short tons (560 t) | White Sands Missile Range | 6 October 1976 |

| Misers Bluff Phase II | ANFO | 1 & 6-simultaneous tests × 120 short tons (110 t) | Planet Ranch, Arizona | Summer 1978 |

| Distant Runner | ANFO | 2 tests × 120 short tons (110 t) | White Sands Missile Range | 1981 |

| Mill Race | ANFO | 620 short tons (560 t) | White Sands Missile Range | 16 September 1981 |

| Direct Course | ANFO | 609 short tons (552 t) | White Sands Missile Range | 26 October 1983 |

| Minor Scale | ANFO | 4,744 short tons (4,304 t) | White Sands Missile Range | 27 June 1985 |

| Misty Picture | ANFO | 4,685 short tons (4,250 t) | White Sands Missile Range | 14 May 1987 |

| Misers Gold | ANFO | 2,445 short tons (2,218 t) | White Sands Missile Range | 1 June 1989 |

| Distant Image | ANFO | 2,440 short tons (2,210 t) | White Sands Missile Range | 20 June 1991 |

| Minor Uncle | ANFO | 2,725 short tons (2,472 t) | White Sands Missile Range | 10 June 1993 |

| Non Proliferation Experiment | ANFO | 1,410 short tons (1,280 t) | Nevada Test Site | 22 September 1993 |

Other smaller tests include Air Vent I and Flat Top I-III series of 20 tons TNT at Nevada Test Site in 1963-64, Pre Mine Throw and Mine Throw in 1970–1974, Mixed Company 1 & 2 of 20 tons TNT, Middle Gust I-V series of 20 or 100 tons TNT in early 1970s, Pre Dice Throw and Pre Dice Throw II in 1975, Pre-Direct Course in 1982, SHIST in 1994, and the series Dipole Might in the 1990s and 2000s. Divine Strake was a planned test of 700 tons ANFO at the Nevada Test Site in 2006, but was cancelled.

Rank order of largest conventional explosions/detonations by magnitude

These yields are approximated by the amount of the explosive material and its properties. They are rough estimates and are not authoritative.

| Event | Location | Date | Approximate yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| T. A. Gillespie Company Shell Loading Plant explosion | Sayreville, New Jersey | 4 October 1918; 6 October 1918 | 6.0 kt of TNT (25.5 TJ) |

| Minor Scale and Misty Picture tests | White Sands Missile Range | 27 June 1985; 14 May 1987 | 4.0 kt of TNT (17 TJ) |

| Heligoland/British Bang test | Heligoland island | 18 April 1947 | 3.2 kt of TNT (13 TJ) |

| Halifax Explosion | Halifax, Nova Scotia | 6 December 1917 | 2.9 kt of TNT (12 TJ) |

| Texas City disaster | Texas City, Texas | 16 April 1947 | 2.7–3.2 kt of TNT (11–13 TJ) |

| Evangelos Florakis Naval Base explosion | Evangelos Florakis Naval Base, Cyprus | 11 July 2011 | 2–3.2 kt of TNT (9–13 TJ) |

| RAF Fauld Explosion | Staffordshire, UK | 27 November 1944 | 2 kt (8.4 TJ) |

| Port Chicago disaster | Port Chicago, California | 17 July 1944 | 1.6–2.2 kt of TNT (7–9 TJ) |

| Oppau explosion | Oppau, Ludwigshafen, Germany | 21 September 1921 | 1–2 kt of TNT (4-8 TJ) |

| N1 launch explosion | Baikonur Cosmodrome Site 110 | 3 July 1969 | 1 kt of TNT (4 TJ) |

See also

Notes

- ↑ After the leader of the Spanish forces, Alessandro Farnese.

- ↑ First NH4NO3 → N2O + 2H2O + 36 kJ/mole, followed by N2O → N2 + ½O2 + 82 kJ/mole of N2O. This gives a total of 118 kJ for 80 grams of NH4NO3, or 1475 kJ/kg. Since a kiloton is defined as 4184 kJ/kg, each kiloton of NH4NO3 gives 0.35 kilotons of explosive power. So 7700 tonnes is about 2.7 kilotons explosive.

References

- ↑ White, Jay (1994). "Exploding Myths: The Halifax Explosion in Historical Context". In Ruffman, Alan; Howell, Colin D. Ground Zero: A Reassessment of the 1917 explosion in Halifax. Nimbus Publishing. pp. 266, 292. ISBN 978-1551090955.

- ↑ National Fire Protection Association (2005). User's Manual for NFPA 921. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 408

- ↑ "Explosion". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ Friel, Ian (12 August 2014). "The Age of Hell Burners". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ Weintz, Steve (8 September 2015). "Hellburners Were the Renaissance's Tactical Nukes". War Is Boring. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ "The Blast that nearly destroyed Beijing - The World of Chinese". www.theworldofchinese.com.

- ↑ "Fort Negro (Fort Gadsden)". BlackHistory.com. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ Horne, Gerald (2012). Negro comrades of the Crown : African Americans and the British Empire fight the U.S. before emancipation (1. publ. in paperback. ed.). New York: New York University Press. p. 83. ISBN 1479876399.

- ↑ "Deadliest Shot in American History?". Prospect Bluff Historic Sites. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ "Fort Gadsden and the "Negro Fort" on the Apalachicola". Fort Gadsden Historic Site, Florida. ExploreSouthernHistory.com. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ Marshman, John Clark (1867). The History of India, Volume III. p. 340.

- 1 2 3 "Mill Rock Island – Historical Sign". nycgovparks.org. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- 1 2 Whitt, Toni (2 June 2006). "The East River is Cleaner Now. The Water Birds Say So". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ↑ Montañés, El Diario. "El Machichaco explotó dos veces".

- ↑ http://naufragios.es/index.php/naufragios-historicos/86-otros-naufragios-historicos/siglo-xix/259-efemerides-santander-3-de-noviembre-de-1893-la-terrible-tragedia-del-cabo-machichaco%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D

- ↑ "Dynamite explosion in Braamfontein". South African History Online. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ "Town Razed And Death Reveled". The Athens Messenger. Athens, Ohio. 17 October 1907. p. 1. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013.

- ↑ "Ship Destroyed by Dynamite Explosion". Popular Mechanics: 656. May 1913.

- ↑ "Gedenkstätten in Quickborn". Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ↑ Ute, Daniel (1997). The War from Within: German Working-Class Women in the First World War. Berg. p. 115. ISBN 978-0854968923.

- ↑ "Traces of the Pilsen History". Official website of the City of Pilsen. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ↑ Simpson, David; Ruffman, Alan (1994). "Explosions, Bombs and Bumps: Scientific Aspects of the Explosion". In Ruffman, Alan; Colin D. Howell. Ground Zero: A Reassessment of the 1917 explosion in Halifax. Nimbus Publishing. p. 288. ISBN 978-1551090955.

- ↑ Malone, Bridget; Epstein, Sue (4 October 1998). "For 3 days, the ground shook in South Amboy". The Star-Ledger.

- ↑ Gabrielan, Randall (2012). Explosion at Morgan: The World War I Middlesex Munitions Disaster. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-517-6. p. 84.

- ↑ China Monthly Review. 88. Millard Publishing Company, Incorporated. 1939. p. 134.

Held responsible for the explosion that wrecked the Hirakata munitions depot, north of Osaka, on March 1, two high Army officers were placed on the reserve list, while a captain was suspended from his duties by the War Office, Domei reported.

- ↑ Cowley, R Adams; Edelstein, Sol; Silverstein, Martin Elliot (1982). Mass Casualties, a Lessons Learned Approach: Accidents, Civil Disorders, Natural Disasters, Terrorism. U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. p. 305.

- ↑ "Smederevo". Archived from the original on 2006-09-26. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ↑ "Smederevo – Razaranja" (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 2006-09-29. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ↑ Blair, Clay (1996). Hitler's U-boat War: The Hunters, 1939–1942. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-58839-1.

- ↑ Rohwer, J.; Hummelchen, G. (1992). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-105-9.

- ↑ William R. Kennedy, Jr. (March 1986). "Technical Report LA-10605-MS: Fallout Forecasting — 1945 Through 1962" (PDF). Los Alamos National Laboratory. , page 3.

- ↑ "Port Chicago Naval Magazine Explosion on 17 July 1944: Court of Inquiry: Finding of Facts, Opinion and Recommendations, continued..." US Navy. Archived from the original on 2000-09-19. 1780 tons of HE on ship plus 199 tons of black powder; docks had 146 tons of HE plus 11 tons powder.

- ↑ Allen, Robert L. (1993). The Port Chicago Mutiny. Amistad. ISBN 978-1-56743-010-3.

- ↑ ja:二又トンネル爆発事故(in Japanese)

- ↑ US Army Field Manual 5–250: Explosives and Demolition, page 1-2.

- ↑ "Der Tag, an dem Helgoland der Megabombe trotzte". Spiegel Online. 13 April 2007. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ↑ de Quetteville, Harry (11 April 2008). "Island levelled by British to be whole again". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ WILLMORE, PL (1947). "Seismic Aspects of the Heligoland Explosion". Nature. 160 (4063): 350. Bibcode:1947Natur.160..350W. doi:10.1038/160350a0.

- 1 2 Willmore, PL (1949). "Seismic Experiments on the North German Explosions, 1946 to 1947". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 242 (843): 123–151. Bibcode:1949RSPTA.242..123W. doi:10.1098/rsta.1949.0007. ISSN 0080-4614. JSTOR 91443.

- ↑ "Ocean Liberty – Cedre". Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ↑ United States Congress Senate Committee on Appropriations (1960). Hearings. University of Michigan. p. 543.

On July 15, 1949, one-third of the people of Prum in Germany lost their homes when ammunition stored in a large concrete pillbox exploded and covered the hillside with debris.

- ↑ "Una hecatombe". El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). 14 September 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ Armando Caicedo Garzón (4 December 1991). "Clave 1956 Explosion En Cali". El Tiempo.

- ↑ "Aug 7, 1956: Mysterious explosions in Colombia". This Day in History. The History Channel. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ Kelso, Jack R.; Clifford, Jr., C. C. (June 1964). Preliminary Report Operation Blowdown. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Steve Kurak (September 1967). "Operation Chase". United States Naval Institute Proceedings: 40–46.

- ↑ Zak, Anatoly (13 May 2013). "ROCKETS: Launchers: N1 Moon Rocket".

- 1 2 "The second launch of the N1 rocket". www.russianspaceweb.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ↑ Harney, Robert C. (September 2009). "Inaccurate Prediction of Nuclear Weapons' Effects and Possible Adverse Influences on Nuclear Terrorism Preparedness". Homeland Security Affairs. 5 (3). Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California.

- ↑ Sisemore, Clyde (July 19, 1973). "Analyzing of Surface-Motion Data from Old Reliable Mine Blast". U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Scientific and Technical Information.

- ↑ "The Flixborough disaster – Report of the Court of Inquiry" (PDF). Department of Employment. 1975.

- ↑ Seconds From Disaster, Discovery Channel

- ↑ "Fireworks suspect charged with deaths". news.google.com. The Spokesman-Review. 30 May 1983. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ↑ "Nuclear Effects Testing". GlobalSecurity.org.

- ↑ TECH REPS INC ALBUQUERQUE NM (1986). "Minor Scale Event, Test Execution Report" (PDF).

- ↑ Reed, Jack W.; Zehrt, Jr., William H. (30 June 1998). "Community Damages from the Pepcon Explosion, 1988". DOD Explosives Safety Board. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "The PEPCON Explosion". Exponent Engineering and Scientific Consulting. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ Routley, J. Gordon, Fire and Explosions at Rocket Fuel Plant, Henderson, Nevada (PDF), Federal Emergency Management Agency, United States Fire Administration, National Fire Data Center, retrieved 20 August 2013

- ↑ "Russia remembers 1989 Ufa train disaster". RIA Novosti. 4 June 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- ↑ Select Committee of the United States House of Representatives (3 January 1999). "Satellite Launches in the PRC: Loral". U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns with the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ Long March Rocket Explodes – 長征火箭爆炸 长征火箭爆炸

- ↑ "Firework Disaster Enschede 13 May 2000". stop-fireworks.org. Archived from the original on 14 May 2010.

- ↑ T. Bedford, P. H. A. J. M. van Gelder, 2003, "Safety and reliability: proceedings of the ESREL 2003 European safety and reliability conference", p.1688

- ↑ Barbier, Pascal (2003). "Urban Growth Analysis Within a High Technological Risk Area: Case of AZF Factory Explosion in Tolouse (France)". Ecole Nationale des Sciences Géographiques.

- ↑ James Brooke (24 April 2004). "North Korea Appeals for Help After Railway Explosion". New York Times. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ↑ "Analysis of the Buncefield Oil Depot Explosion 11 December 2005". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ "Explosions rock Maputo Airport in Mozambique". Huliq. Associated Press. 23 March 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ↑ "Weapons depot blasts kill 93 in Mozambique". USA Today. Associated Press. 25 March 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ↑ "Evacuation from Puerto Rico fire". BBC News. 24 October 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ↑ Kovaleva, Olga (19 November 2009). "Explosion at Ulyanovsk Russian Military Depot Kills Several and Devastates Town". UNVA Magazine. University of Northern Virginia. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ↑ Super Suku Tube (14 April 2010), Ulyanovsk, Russia: Massive oil tank explosion, YouTube

- ↑ "Archived copy" Βιβλική καταστροφή στην Κύπρο – 16 νεκροί και δεκάδες τραυματίες – Εξετάζεται ΚΑΙ το ενδεχόμενο δολιοφθοράς [Biblical destruction in Cyprus – 16 dead and dozens wounded – Sabotage considered] (in Greek). NewsIt. 11 July 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Έγιναν τραγικά λάθη; [Tragic Mistakes Made?], MegaTV.com, 11 July 2011, archived from the original on 19 March 2012

- ↑ "M 3.0 – CYPRUS REGION – 11 July 2011 02:47:52 UTC". Centre Sismologique Euro-Méditerranéen.

- ↑ "4,000 tons of shells explode in Central Russia, leave mushroom cloud-like plume of smoke (PHOTOS, VIDEO) Published time: October 09, 2012 09:22".

- ↑ "So THAT'S why they don't let you smoke around munition dumps! 'Cigarette' sparks blast a quarter of the size of Hiroshima at Russian military testing site".

- ↑ Mungin, Lateef (18 April 2013). "Explosion hits fertilizer plant north of Waco, Texas". CNN. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ↑ Crawford, Selwyn (17 April 2013). "Live video: Fertilizer plant explosion injures dozens in West, near Waco". Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ↑ "Central Texas fertilizer blast triggers 2.1 magnitude quake". WFAA-TV. 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013.

- ↑ "Magnitude 2.1 – CENTRAL TEXAS". U.S. Geological Survey. 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 22 April 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ↑ Loftis, Randy Lee (16 May 2013). "Analysis: West Fertilizer report details sequence of a catastrophe". Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ Canada, Government of Canada, Transportation Safety Board of. "Lac-Mégantic runaway train and derailment investigation summary - Railway Investigation Report R13D0054 - Transportation Safety Board of Canada". www.tsb.gc.ca.

- ↑ "China explosions: Tianjin blasts 'on seismic scale'". BBC. 13 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ "Tianjin explosion: China sets final death toll at 173, ending search for survivors". The Guardian. 12 September 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ↑ "Nuclear effects testing". GlobalSecurity.org.

- ↑ Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986). Page 654.

- ↑ Bainbridge, K.T., Trinity (Report LA-6300-H), Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. Page 7.