Foreign relations of North Korea

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of North Korea |

|

|

|

Related topics |

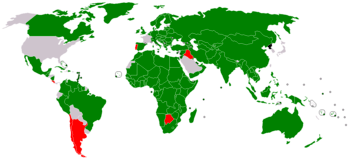

The foreign relations of North Korea – officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) – have been shaped by its conflict with capitalist countries like South Korea and its historical ties with world communism. Both the government of the DPRK and the government of South Korea (officially the Republic of Korea) claim to be the government of the whole of Korea. The Korean War in the 1950s failed to resolve the issue, leaving the DPRK locked in a military confrontation with South Korea and the United States Forces Korea across the Demilitarized Zone. At the start of the Cold War, the DPRK only had diplomatic recognition by Communist countries. Over the following decades, it established relations with developing countries and joined the Non-Aligned Movement. When the Eastern Bloc collapsed in the years 1989–1991, the DPRK made efforts to improve its diplomatic relations with developed capitalist countries. At the same time there were international efforts to resolve the confrontation on the Korean peninsula, especially when the North acquired nuclear weapons after the demise of the Soviet Union, its main economic backer.[1] In 2018, Kim Jong-un made a sudden peace overture towards South Korea and the United States.

Principles

The Constitution of the DPRK establishes the country's foreign policy. While Article 2 of the constitution describes the country as a "revolutionary state," Article 9 says that the country will work to achieve Korean reunification, maintain state sovereignty and political independence, and "national unity."[2][3]

Many articles specifically outline the country's foreign policy. Article 15 says that the country will "protect the democratic national rights of Korean compatriots overseas and their legitimate rights and interests as recognized by international law" and Article 17 explicates the basic ideals of the country's foreign policy:[3]

- Basic ideals of their foreign policy are "independence, peace and friendship"[3]

- Establishment of political, economic, cultural, and diplomatic relations with "friendly countries" on the principles of "complete equality, independence, mutual respect, non-interference in each other’s affairs and mutual benefit."[3]

- Unifying with "peoples of the world who defend their independence"[3]

- Actively supporting and encouraging "struggle of all people who oppose all forms of aggression and interference and fight for their countries' independence and national and class emancipation."[3]

Other parts of the constitution explicate other foreign policies. Article 36 says that foreign trade by the DPRK will be conducted "by state organs, enterprises, and social, cooperative organizations" while the country will "develop foreign trade on the principles of complete equality and mutual benefit." Article 37 adds that the country will encourage "institutions, enterprises and organizations in the country to conduct equity or contractual joint ventures with foreign corporations and individuals, and to establish and operate enterprises of various kinds in special economic zones." Furthermore, Article 38 says that the DPRK will implement a protectionist tariff policy "to protect the independent national economy" while Article 59 says the country's armed forces will "carry out the military-first revolutionary line." In terms of other foreign policy, Article 80 says that the country will grant asylum to foreign nationals who have been persecuted "for struggling for peace and democracy, national independence and socialism or for the freedom of scientific and cultural pursuits."[3]

Ultimately, however, as explicated in Articles 100–103 and 109, the chairman of the National Defense Commission (NDC) is the supreme leader of the country, with a term that is the same as members of the Supreme People's Assembly or SPA (five years), as is established in article 90, directing the country's armed forces, and guiding overall state affairs, but is not determined by him alone since he is still accountable to the SPA.[3] Rather, the NDC chairman works to defend the state from external actors. Currently, Kim Jong-un, is the elected Secretary of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK), chairman of the NDC, and holder of numerous other leadership positions. The Constitution also delineates, in article 117, that the President of SPA Presidium, which can convene this assembly, represents the state and receives "credentials and letters of recall from envoys accredited by other countries." Additionally, the cabinet of the DPRK has the authority to "conclude treaties with foreign countries and conduct external affairs" as noted in Article 125.[3]

The DPRK is one of the few countries in which the giving of presents still plays a significant role in diplomatic protocol, with Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) reporting from time to time the country's leader received a floral basket or other gift from a foreign leader or organization.[4][5] During a 2000 visit to Pyongyang, U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright gave Kim Jong-il a basketball signed by Michael Jordan, as he took an interest in NBA basketball.[6] The DPRK takes its defense seriously, threatening countries they see as threatening their sovereignty, and restricts the activities of foreign diplomats.[7][8]

History

.jpg)

After 1945, the Soviet Union supplied the economic and military aid that enabled the DPRK to mount its invasion of South Korea in 1950. Soviet aid and influence continued at a high level during the Korean war. This was only the beginning of the DPRK as governed by the faction which had its roots in an anti-Japanese Korean nationalist movement based in Manchuria and China, with Kim Il-sung participating in this movement and later forming the Korean Workers' Party.

The assistance of Chinese troops, after 1950, during the war and their presence in the country until 1958 gave China some degree of influence in the DPRK.[9]

In 1961, the DPRK concluded formal mutual security treaties with the Soviet Union and China, which have not been formally ended. In the case of China, Kim Il-sung and Chou En-Lai signed the Sino-North Korean Mutual Aid and Cooperation Friendship Treaty, whereby Communist China pledged to immediately render military and other assistance by all means to its ally against any outside attack.[10] The treaty says, in short that:

THE Chairman of the People's Republic of China and the Presidium of the Supreme People's Assembly of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, determined, in accordance with Marxism–Leninism and the principle of proletarian internationalism and on the basis of mutual respect for state sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other's internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and mutual assistance and support, to make every effort to further strengthen and develop the fraternal relations of friendship, co-operation and mutual assistance between the People's Republic of China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, to jointly guard the security of the two peoples, and to safeguard and consolidate the peace of Asia and the world...[Article II:]The Contracting Parties will continue to make every effort to safeguard the peace of Asia and the world and the security of all peoples...[Article II:] In the event of one of the Contracting Parties being subjected to the armed attack by any state or several states jointly and thus being involved in a state of war, the other Contracting Party shall immediately render military and other assistance by all means at its disposal...[Article V:] The Contracting Parties, on the principles of mutual respect for sovereignty, non-interference in each other's internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit and in the spirit of friendly co-operation, will continue to render each other every possible economic and technical aid in the cause of socialist construction of the two countries and will continue to consolidate and develop economic, cultural, and scientific and technical co-operation between the two countries...[Article VI:] The Contracting Parties hold that the unification of Korea must be realized along peaceful and democratic lines and that such a solution accords exactly with the national interests of the Korean people and the aim of preserving peace in the Far East.[10]

This treaty was prolonged twice, in 1981 and 2001, with a validity until 2021.

For most of the Cold War, the DPRK avoided taking sides in the Sino-Soviet split, but was originally only recognized by countries in the Communist Bloc until 1958 when Algeria recognized it.[11]

East Germany was an important source of economic cooperation for the DPRK. The East German leader, Erich Honecker, who visited in 1977, was one of Kim Il-sung's closest foreign friends.[12] In 1986, the two countries signed an agreement on military co-operation.[13] Kim was also close to maverick Communist leaders, Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, and Nicolae Ceaușescu of Romania.[14] The DPRK began to play a part in the global radical movement, forging ties with such diverse groups as the Black Panther Party of the USA,[15] the Workers Party of Ireland,[16] and the African National Congress.[17] As it increasingly emphasized its independence, the DPRK began to promote the doctrine of Juche ("self-reliance") as an alternative to orthodox Marxism-Leninism and as a model for developing countries to follow.[18]

When North-South dialogue started in 1972, the DPRK began to receive diplomatic recognition from countries outside the Communist bloc. Within four years, the DPRK was recognized by 93 countries, on par with South Korea's 96. The DPRK gained entry into the World Health Organization and, as a result, sent its first permanent observer missions to the United Nations.[19] In 1975, it joined the Non-Aligned Movement.[20]

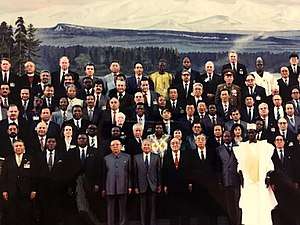

During the 1980s, the pace of the DPRK's establishment of new diplomatic relations slowed considerably.[21][22] Following Kim Il-sung's 1984 visit to Moscow, there was a dramatic improvement in Soviet-DPRK relations, resulting in renewed deliveries of advanced Soviet weaponry to the DPRK and increases in economic aid. In 1989, as a response to the 1988 Seoul Olympics, North Korea hosted the 13th World Festival of Youth and Students in Pyongyang.[23][24]

South Korea established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1990 and the People's Republic of China in 1992, which put a serious strain on relations between the DPRK and its traditional allies. Moreover, the demise of Communist states in Eastern Europe in 1989 and the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 had resulted in a significant drop in communist aid to DPRK, resulting in largely decreased relations with Russia. Subsequently, South Korea developed the "sunshine policy" towards the DPRK, aiming for peaceful Korean reunification. This policy ended in 2009.

In September 1991, the DPRK became a member of the United Nations. In July 2000, it began participating in the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), as Foreign Minister Paek Nam-sun attended the ARF ministerial meeting in Bangkok 26–27 July. The DPRK also expanded its bilateral diplomatic ties in that year, establishing diplomatic relations with Italy, Australia and the Philippines. The United Kingdom established diplomatic relations with the DPRK on 13 December 2000,[25] as did Canada in February 2001,[26] followed by Germany and New Zealand on 1 March 2001.[27][28]

.jpg)

In 2006, the DPRK test-fired a series of ballistic missiles, after Chinese officials had advised DPRK authorities not to do so. As a result, Chinese authorities publicly rebuked what the west perceives as China's closest ally, and supported the UN Security Council Resolution 1718, which imposed sanctions on DPRK.[9] At other times however, China has blocked United Nations resolutions threatening sanctions against the DPRK.[29] In January, 2009, China's president Hu Jintao and the DPRK's supreme leader Kim Jong-il exchanged greetings and declared 2009 as the "year of China-DPRK friendship", marking 60 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries.[30]

On 28 November 2010, as part of the United States diplomatic cables leak, WikiLeaks and media partners such as The Guardian published details of communications in which Chinese officials referred to the DPRK as a "spoiled child" and its nuclear program as "a threat to the whole world's security" while two anonymous Chinese officials claimed there was growing support in Beijing for Korean reunification under the South's government.[31][32] A 2013 article by Deng Yuwen, deputy editor of Study Times, the journal of the Central Party School of the Communist Party of China also promoted reunification of North and South Korea.[33]

Inter-Korean relations

In August 1971, both North and South Korea agreed to hold talks through their respective Red Cross societies with the aim of reuniting the many Korean families separated following the division of Korea after the Korean War. After a series of secret meetings, both sides announced on 4 July 1972, an agreement to work toward peaceful reunification and an end to the hostile atmosphere prevailing on the peninsula. Dialogue was renewed on several fronts in September 1984, when South Korea accepted the North's offer to provide relief goods to victims of severe flooding in South Korea.

In a major initiative in July 1988, South Korean President Roh Tae-woo called for new efforts to promote North-South exchanges, family reunification, inter-Korean trade and contact in international forums. Roh followed up this initiative in a UN General Assembly speech in which South Korea offered to discuss security matters with the North for the first time. In September 1990, the first of eight prime minister-level meetings between officials of the DPRK and South Korea took place in Seoul, beginning an especially fruitful period of dialogue. The prime ministerial talks resulted in two major agreements: the Agreement on Reconciliation, Nonaggression, Exchanges, and Cooperation (the Basic Agreement) and the Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula (the Joint Declaration). The Joint Declaration on denuclearization was initiated on 13 December 1991. It forbade both sides to test, manufacture, produce, receive, possess, store, deploy, or use nuclear weapons and forbade the possession of nuclear reprocessing and uranium enrichment facilities. On 30 January 1992, the DPRK also signed a nuclear safeguards agreement with the IAEA, as it had pledged to do in 1985 when acceding to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. This safeguards agreement allowed IAEA inspections to begin in June 1992.

As the 1990s progressed, concern over the North's nuclear program became a major issue in North-South relations and between the DPRK and the US. By 1998, South Korean President Kim Dae-jung announced a Sunshine Policy towards the DPRK. This led in June 2000 to the first Inter-Korean summit, between Kim Dae-jung and Kim Jong-il.[34] In September 2000, the North and South Korean teams marched together at the Sydney Olympics.[35] Trade increased to the point where South Korea became the DPRK's largest trading partner.[36] Starting in 1998, the Mount Kumgang Tourist Region was developed as a joint venture between the government of the DPRK and Hyundai.[37] In 2003, the Kaesong Industrial Region was established to allow South Korean businesses to invest in the North.[38]

In 2007, South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun held talks with Kim Jong-il in Pyongyang.[39][40][41][42] On October 4, 2007, South Korean President Roh and Kim signed a peace declaration. The document called for international talks to replace the Armistice which ended the Korean War with a permanent peace treaty.[43] The Sunshine Policy was formally abandoned by subsequent South Korean President Lee Myung-bak in 2010.[44]

The Kaesong Industrial Park was closed in 2013, amid tensions about the DPRK's nuclear weapons program. It reopened the same year but closed again in 2016.[45][46]

In 2017 Moon Jae-in was elected President of South Korea with promises to return to the Sunshine Policy.[47] In his New Year address for 2018, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un proposed sending a delegation to the upcoming Winter Olympics in South Korea.[48] The Seoul–Pyongyang hotline was reopened after almost two years.[49] North and South Korea marched together in the Olympics opening ceremony and fielded a united women's ice hockey team.[50] North Korea sent an unprecedented high-level delegation, headed by Kim Yo-jong, sister of Kim Jong-un, and President Kim Yong-nam, as well as athletes and performers.[51]

On 27 April, the 2018 inter-Korean summit took place between President Moon Jae-in and Kim Jong-un on the South Korean side of the Joint Security Area. It was also the first time since the Korean War that a North Korean leader had entered South Korean territory.[52] The summit ended with both countries pledging to work towards complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.[53][54] They agreed to work to remove all nuclear weapons from the Korean Peninsula and, within the year, to declare an official end to the Korean War.[55] As part of the Panmunjom Declaration which was signed by leaders of both countries, both sides also called for the end of longstanding military activities in the region of the Korean border and a reunification of Korea.[56] Also, the leaders of the region's two divided states have agreed to work together to connect and modernise their border railways.[57]

Moon and Kim met the second time on 26 May.[58] Their second summit was unannounced, held in the North Korean portion of Joint Security Area and concerned Kim's upcoming summit with US President Donald Trump.[59][60] US President Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un met on 12 June 2018 in Singapore and endorsed the Panmunjom Declaration.

Nuclear weapons program

The DPRK's nuclear research program started with Soviet help in the 1960s, on condition that it joined the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). In the 1980s an indigenous nuclear reactor development program started with a small experimental 5 MWe gas-cooled reactor in Yongbyon, with a 50 MWe and 200 MWe reactor to follow. Concerns that the DPRK had non-civilian nuclear ambitions were first raised in the late 1980s and almost resulted in their withdrawal from the NPT in 1994. However, the Agreed Framework and the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO) temporarily resolved this crisis by having the US and several other countries agree that in exchange for dismantling its nuclear program, two light-water reactors (LWRs) would be provided with moves toward normalization of political and economic relations. This agreement started to break down from 2001 because of slow progress on the KEDO light water reactor project and U.S. President George W. Bush's Axis of Evil speech. After continued allegations from the United States, the DPRK declared the existence of uranium enrichment programs during a private meeting with American military officials. The DPRK withdrew from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty on 10 January 2003. In 2006, North Korea conducted its first nuclear test.[61]

In the third (and last) phase of the fifth round of six-party talks were held on 8 February 2007, and implementation of the agreement reached at the end of the round has been successful according to the requirements of steps to be taken by all six parties within 30 days, and within 60 days after the agreement, including normalization of US-DPRK and Japanese-DPRK diplomatic ties, but on the condition that the DPRK ceases to operate its Yongbyon nuclear research centre.[62][63]

The DPRK conducted further nuclear tests in 2009, 2013, January and September 2016, and 2017.[64][65][66] In 2018, North Korea ceased conducting nuclear and missile tests. Kim Jong-un signed the Panmunjom Declaration committing tp "denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula" and affirmed the same commitment in a subsequent meeting with US President Donald Trump.

Bilateral relations

The DPRK is often perceived as the "Hermit kingdom", completely isolated from the rest of the world, but the DPRK maintains diplomatic relations with 164 independent states.[67][68][69][70]

The country also has bilateral relations with the State of Palestine, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, and the European Union.[71][72][73][74][75][76]

European Union (EU)

The DPRK had economic interests in the European Union. In March 2002, the DPRK's trade minister visited certain EU member states, including Belgium, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Sweden, and the country has also been known to send short-term trainees to Europe. Additionally, workshops regarding DPRK's economic reform have taken place with EU diplomats and economists as participants.[77] The EU still is concerned about human rights violations they allege are occurring within the country and has hosted talks with anti-DPRK defectors.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan and North Korea established diplomatic relations on 26 December 1973.[11]

Albania

Diplomatic relations with Albania were established on November 28, 1948.[78] Albania's communist government led by Enver Hoxha was often likened to the isolation of North Korea. In 1961, Albania and the DPRK signed a joint declaration of friendship.[79] In the 70s, relations between the two countries deteriorated, with Hoxha writing in June 1977 that Kim Il Sung and the leadership of the Korean Workers Party had betrayed the Korean people by accepting for aid from other countries, primarily between countries in the Eastern Bloc and non-aligned countries such as Yugoslavia. As a result, relations between North Korea and Albania would remain low until Hoxha's death in 1985.

In 2011, the President of the Supreme People's Assembly Kim Yong-nam sent a congratulatory message to Albanian President Bujar Nishani on the 100th Anniversary of the Independence of Albania.[80]

Algeria

On 25 September 1958, Algeria became the first non-Marxist country to establish diplomatic relations with North Korea.[11] Initially, relations were with the National Liberation Front since the Algerian War was still ongoing and the country had not gained its independence yet.[81] North Korea maintains an embassy in the country.[82]

Angola

The DPRK has had a strong relationship with Angola from the time of Angola's struggle for independence. It is estimated that 3,000 DPRK troops and a thousand advisers took part in the Angolan Civil War in the 1970s and 1980s, and fighting against the apartheid South African military.[17] In 2011, Angola purchased naval patrol boats from the DPRK.[83]

Armenia

The establishment of diplomatic relations between Armenia and the DPRK started in 1992 upon Armenia's independence from the USSR, but never progressed due to Armenia's protest of North Korea's numerous human right's violations, nuclear weapons program, and its harsh treatment of the North Korean populace .[84]

Australia

Australia and the DPRK maintain diplomatic relations.[85] Neither country has a diplomatic presence in the other country, and relations are strained, due to disputes such as over the DPRK's nuclear program and alleged drug trafficking.[86][87]

In April 2017, the DPRK claimed that Darwin in Australia was being used by the United States to prepare for nuclear war, following the deployment of 1250 US troops to the area.[88]

Benin

After the People's Republic of Benin was proclaimed in 1975, the government established good relations with several Communist countries, including the DPRK. These good relations have continued to the present day.[89]

Botswana

Botswana had good relations with the DPRK from 1974.[90][91][92][93][94] In years that followed, the first independent leader of Botswana, President Seretse Khama, made a state visit to Pyongyang, and several DPRK martial arts instructors were commissioned to train the Botswana Police Service in unarmed combat but did not stay long. Beyond this, the DPRK used the Mansudae Overseas Projects company to build the Three Dikgosi Monument, which has been a source of controversy in the Western media, and hired medical professionals to supplement the ones in their country.[95][96]

However, Botswana broke off diplomatic ties in 2014, after suspending bilateral cooperation the previous year, over alleged human rights violations.[97] In the following year, Ian Khama, the president of Botswana, declared that the country was an "opponent" and went on to claim that "the aggressive attitude of North Korea threatens peace in the region and therefore threatens world peace...I think the North Korean leadership is living in the Stone Age."[98]

Brazil

Brazil did not establish diplomatic relations with the DPRK until 2001. That year, during the administration of Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso, diplomatic relations were quietly established between the DPRK and Brazil. After relations were established in 2001, several years passed before the actual opening of the embassies. DPRK's embassy in Brazil was inaugurated in 2005, and the Brazilian embassy in Pyongyang was only opened when the first Brazilian ambassador to the DPRK was appointed in 2009.[99] Even so, the Brazilian government has condemned military tests by the DPRK's government over the years.[100][101]

Bulgaria

Bulgaria and the DPRK generally have good relations. Diplomatic relations between the countries were established on 29 November 1948, and a bilateral agreement on cultural and scientific cooperation was signed in 1970. Kim Il-sung visited the People's Republic of Bulgaria for the first time in the 1950s, and again in 1975. Bulgarian volunteers provided basic aid to DPRK during the Korean war by providing items such as clothing and foodstuffs.[102] Even after the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, the countries retained active diplomatic relations. The foreign language institute in Pyongyang maintains a Bulgarian language department. In the past, the two countries also cooperated closely in the sphere of sports, and still maintain such cooperation albeit to a lesser degree. In 2017, the primer of the DPRK, Pak Pong Ju, sent a message to Boyko Borisov, congratulating him on his appointment as prime minister of Bulgaria, saying that "relations of friendship and cooperation between the two countries" should favorably develop "in common interests." The same day, the DPRK's foreign minister, Ri Yong Ho, sent a message, similar in content, to Ekaterina Gecheva-Zaharieva, congratulating her on "appointment as vice prime minister and foreign minister of Bulgaria."[103]

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso and the DPRK established strong relations during the Cold War, and these have been continued.

Relations between Burkina Faso and the DPRK have historically been relatively close. Neither country maintains an embassy in the other, although the DPRK used to have an ambassador in Ouagadougou.[104] Relations were especially close during the Cold War, with the DPRK providing military equipment to the army of the Republic of Upper Volta, along with agricultural, military and technical assistance over the years.[105][106][107][108][109] Even Thomas Sankara, a Marxist and revolutionary, visited Pyongyang several times, leading to a DPRK–Burkina Faso Friendship Association in place at the time. Even during the reign of Blaise Compaoré, the successor of Sankara, cultural and trade relations remained strong, along with the DPRK completing construction, in 1998, five small water reservoirs in the country.[110][111][112][113]

In recent years, Burkina Faso has strayed from traditional relations with the DPRK, by voting, in 2009, in favor of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1874, which imposed further economic sanctions on the DPRK, saying that they voted in such a manner due to their commitment to a "nuclear weapon-free" world.[114]

Burundi

Burundi and the DPRK have good relations. In 2011, Burundi purchased weapons from the DPRK. In 2016, the DPRK's Kim Yong-nam visited Burundi.[115]

Cambodia

Cambodia and the DPRK generally have good relations. When the Khmer Rouge was removed by a Vietnamese invasion in 1979, the DPRK supported Norodom Sihanouk in an exile government, and he lived in the DPRK until 1991 when he became King of Cambodia and returned to the country with a bodyguard of individuals from the DPRK.[116] The DPRK has an embassy in Phnom Penh and Cambodia has an embassy in Pyongyang. While the DPRK has built the Angkor Panorama museum within the country, reportedly relations are strained with some saying that Cambodia could cast off the DPRK as a partner although this seems unlikely since the DPRK has asked for help from the country in reducing tensions on the Korean Peninsula.[117] [118][119] In 2016, one United Nations expert claimed that the Cambodia Supreme Court upholding "a life sentence for two top cadres of the 1970s Khmer Rouge found guilty of crimes against humanity" will send a "message" to the leaders of the DPRK even though the said country never supported the Khmer Rouge.[120] More directly, the DPRK has defended Cambodia, saying in later 2016 that a division of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights was operating illegally in the country, saying its operation vioalted the "principle of respect for sovereignty and non-interference in domestic affairs" and that "every year the U.N. raises the issue of human rights while violating the principle of fairness when discussing human rights and showing sympathy for hostile acts against sovereign states."[121]

Canada

Diplomatic relations between Canada and the DPRK were established on February 2001. However, there are no official embassies between the two nations. Canada is represented by the Canadian Ambassador resident in Seoul, and the DPRK is represented by their position in the United Nations. On 25 May 2010, Canada suspended diplomatic relations with the DPRK.[122]

Central African Republic

From 1969, the DPRK maintained a close relationship with the long-time military ruler of the Central African Republic, Jean-Bédel Bokassa, even though he was anti-communist.[123] After he proclaimed himself Emperor in 1976, Bokassa's first foreign visit was to Pyongyang, returning to the country in 1978, signing a treaty of peace and friendship with Kim Il-sung.[124][125] Even after Bokasa was overthrown in 1979, friendly relations continued. By March 1986 it was estimated that the DPRK was supplying 13 technicians to the Central African Republic, seemingly to counter South Korean influence in the country.[126]

China

China and the DPRK share a 1,416-kilometre long border (890 miles) that corresponds to the course of the Yalu and Tumen rivers, which both flow from Heaven Lake on Mount Paektu. The countries have six border crossings between them.[127]

The two countries are generally perceived to be on friendly terms; however, in recent years, there has been growing concern in the PRC over issues such as the DPRK's nuclear weapons program, sinking of the ROKS Cheonan and their bombardment of Yeonpyeong. After the DPRK conducted its first nuclear test in 2006, the Chinese government stated that they were "resolutely opposed to it" and voted for United Nations sanctions against the DPRK.[128]

The Council on Foreign Relations suggests that the PRC's main priority in its bilateral relations with the DPRK is to prevent the collapse of Kim Jong-un's government, concerned that such an event would provoke a surge of DPRK refugees into China. All the while Chinese counterparts are interested in a buffer zone to US-allied South Korea,[129] it also suggests, however, that Chinese-DPRK relations may be soured due to China's concerns about Japan's remilitarization in response to the DPRK's military behaviour.[29]

The PRC permitted the Yanbian Korean Ethnic Group Autonomous Prefecture to conduct border trade with the DPRK in August 1954. In the 1950s, border trade between China and DPRK reached as high as 7.56 million Chinese renminbi. Trade was suspended due to the cultural revolution until a new contract was signed in 1982 between China and the DPRK, which set the Swiss franc as the exchange currency. Since then, PRC-DPRK border trade has increased rapidly with the trade between Jilin Province and the DPRK alone reaching 1.03 million Swiss francs (510K USD).[130] Trade volume amounted to 11.99 million Swiss francs (CHF) in 1983 (5.71M USD), CHF 100 million in 1985 (40.70M USD), CHF 160 million in 1988 (109.34M USD), and CHF 150 million (88.2M USD) in 1990.[130]

The PRC is the DPRK's largest trade partner, while the DPRK ranked 82nd (in 2009) in China's trade partners. China provides about half of all the DPRK's imports and received a quarter of its exports. The PRC's major imports from the DPRK includes mineral fuels (coal), ores, woven apparel, iron and steel, fish and seafood, and stone. DPRK's imports from Mainland China include mineral fuels and oil, machinery, electrical machinery, vehicles, plastic, and iron and steel. The PRC is a major source for DPRK imports of petroleum.[131] In 2009, exports to the DPRK of mineral fuel oil totaled $327 million and accounted for 17% of all Chinese exports to the DPRK. Much of China's trade with the DPRK goes through the port of Dandong on the Yalu River.[132]

During the Korean War from 1950–53, China assisted the DPRK, sending as many as 500,000 soldiers to support DPRK forces. In 1975, Kim Il Sung visited Beijing in a failed attempt to solicit support from China for a military invasion of South Korea.[133] On November 23, 2009, PRC Defence Minister Liang Guanglie visited Pyongyang, the first defense chief to visit since 2006.[134]

Comoros

North Korea has had diplomatic relations with the Comoros since November 13, 1975.[76]

Hong Kong

Hong Kong and the DPRK have had official relations established since 1997, after the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to the People's Republic of China.[135]

Cuba

The DPRK has had diplomatic relations with Cuba since 1960 and maintains an embassy in Havana. Cuba has been one of the DPRK's most consistent allies.[136] The DPRK media portrays Cubans as comrades in the common cause of socialism.[137]

During the Cold War, the DPRK and Cuba forged a bond of solidarity based on their militant positions opposing American power. In 1968 Raul Castro stated their views were "completely identical on everything".[138] Che Guevara, then a Cuban government minister, visited the DPRK in 1960, and proclaimed it a model for Cuba to follow.[139] Cuban leader Fidel Castro visited in 1986.[140] Cuba was one of the few countries that showed solidarity with the DPRK by boycotting the Seoul Olympics in 1988.[138]

In 2016, the Workers Party of Korea and the Communist Party of Cuba met to discuss strengthening ties.[136] After Fidel Castro's death in 2016, the DPRK government declared a three-day mourning period and sent an official delegation to his funeral.[140] Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un visited the Cuban embassy in Pyongyang to pay his respects.[141]

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has friendly relations with the DPRK. After the death of Laurent Kabila, DPRK workers under the Mansudae Overseas Projects constructed a statue commemorating the life of the former leader in Kinshasa.[142] When a DPRK delegation visited the Congo in 2013, the two countries signed a protocol on negotiations and cooperation between their foreign ministries.[89]

In 2016, it was revealed that the Congolese government of Joseph Kabila had purchased pistols and hired military instructors from the DPRK.[115]

Denmark

Denmark is represented in the DPRK through its embassy in Hanoi, Vietnam.[143]

Egypt

The DPRK and Egypt have a long history of good relations. Egypt recognized the DPRK in 1963. It did not recognize South Korea until 1995. The DPRK gave Egypt military aid during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. In the 1980s, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak visited the DPRK four times. Egyptian company Orascom helped create the DPRK's cell phone network. As of September 12, 2017, Egypt announced it was suspending military ties with North Korea.[144]

Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea's first leader, Francisco Macías Nguema, established close ties with the DPRK in 1969. The relationship continued after his overthrow. In 2016, Kim Yong-nam of the DPRK visited Equatorial Guinea and held amicable talks with President Teodoro Obiang.[115]

Ethiopia

Ethiopia has had diplomatic relations with North Korea since the 1970s. North Korea has provided training for Ethiopian militias and special forces, and supplied munitions, tanks, Armoured Personnel Carriers, and artillery. It has also helped establish two arms factories. However, economic relations have become restricted by United Nations sanctions.[145]

Finland

Finland recognised North Korea on 13 April 1973. Diplomatic relations were established on 1 June 1973.[146] Finland has a resident ambassador posted in Seoul. The DPRK owes the government and other private businesses over 30 million Euros that date back to the 1970s. In April 2017 government officials reassured YLE news reporters that they have not forgotten about the debt, and will work to find a solution to their debts.[147]

France

Relations between the French Republic and the DPRK are officially non-existent. France is one of only two European Union members not to maintain diplomatic relations with the DPRK, the other being Estonia.[148][149] There is no French embassy, nor any other type of French diplomatic representation, in Pyongyang, and no DPRK embassy in Paris, although a DPRK diplomatic office is located in nearby Neuilly sur Seine.[150][151] France's official position is that it will consider establishing diplomatic relations with DPRK if and when the latter abandons its nuclear weapons program and improves its human rights record.[150]

Ghana

Ghana and North Korea established diplomatic relations in 1964.[11]

Even before diplomatic relations were established, Ghana had campaigned, along with other African nations, for recognition of North Korea as an observer in the United Nations (UN).[152] Trade relations between the two countries preceded diplomatic relations.[153] North Korea's leader Kim Il-sung shared much in common politically with Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah.[154] After Nkrumah was ousted,[155] North Korea ended up in a diplomatic spat with Ghana, which accused it of training anti-government rebels.[156] By the late-1960s, North Korea was again supporting Ghana as an anti-imperialist force in Africa.[157] In the 1980s, Ghana's Provisional National Defence Council successfully sought aid from North Korea and other socialist countries in order to be more independent from Western powers.[158] An agreement on cultural exchange was signed for 1993–1995.[159]

There was a North Korean embassy in Ghana until it was closed down in 1998.[160] The current North Korean ambassador to Ghana is Kil Mun-yong.[161][162] Trade between the two countries consists mainly of North Korean exports of cement and Ghanaian cocoa, gemstones, and pearls.[163] There is a Korea–Ghana Friendship Association for cultural exchange.[164]

The Gambia

The Gambia and the DPRK have had relations since 1973, with a diplomatic mission of the DPRK opening in 1975.[165] In later years, the DPRK sent karate instructors to the country, and had varying strong bilateral relations between the two countries.[166][167][168][169][170] Hong Son Phy is currently the accredited ambassador to Banjul.[171]

Germany

The relations between Germany and the DPRK date back to 1949, when the governments of East Germany and the DPRK established diplomatic relations. The embassies in Berlin and Pyongyang opened 1954. East Germany used to be one of North Koreas closest allies within the Eastern Communist states, so multiple cooperation agreements and trade ties were established. The Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) remained in a rather hostile position towards the DPRK during the Cold War and only maintained basic diplomatic contact, however in 1981 a delegation of DPRK officials visited Bonn.

After the German reunion Germany maintained a diplomatic mission in the former East German Embassy and officially opened its embassy in Pyongyang in 2001, While the DPRK re-opened its embassy in Berlin the same year. These diplomatic ties are still active, but due to the massive UN sanctions there is only very little economic cooperation between the two countries. Also Germany has continued to condemn the North Korean nuclear program.

Hungary

Relations between the two countries have existed since the Korean War; however, conflicts beginning in the late 1980s strained relations.

When the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 began, roughly 200 of DPRK students joined in; their war experience proved to be of aid to the Hungarian students.[172] In the aftermath of the revolution, Hungarian police and Soviet forces gathered up the students from the DPRK and deported them back to the DPRK, with four of them escaping to Austria.[173][174]

In 1989, Hungary would become the first Eastern Bloc nation to open relations with South Korea; in response, the DPRK withdrew Kim Pyong-il from Hungary and sent him to Bulgaria instead.[175][176] In response, the DPRK referred to the Hungarian decision as a "betrayal", and expelled the Hungarian envoy to Pyongyang.[177] As a result, there was a downturn in bilateral ties which lasted over a decade-and-a-half but in 2004, then-deputy State Secretary Gábor Szentiványi indicated that his government were interested in improving their relations with the DPRK, even though by 2009, the former Hungarian embassy building in Pyongyang remained empty.[178][177]

India

India and the DPRK have growing trade and diplomatic relations. India maintains a fully functioning embassy in Pyongyang and the DPRK has an embassy in New Delhi. India has said that it wants the "reunification" of Korea.[179] Many DPRK nationals receive training in India including in the fields of IT and science and technology. India has a bilateral trade of around half a billion dollars with the DPRK. Also, India is increasingly being asked by the USA to mediate in the Korean peninsula due to its strengthening relations with both the DPRK and South Korea.[180]

India voted in favour of Security Council resolutions 82 and 83 relating to the Korean War. However, India did not support resolution 84 for military assistance to South Korea. As a non-aligned country, India declined to fight against the DPRK. Instead, India decided to send a medical unit to Korea as a humanitarian gesture. The 60th Indian Field Ambulance Unit, a unit of the Indian Airborne Division, was selected to be dispatched to Korea. The unit consisted of 346-men including 14 doctors.[181]

After the Korean War, India again played an important role as the chair of the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission in the Korean peninsula. India established consular relations with the DPRK in 1962 and in 1973, established full diplomatic relations with it.[182] India's relationship with the DPRK has however been affected by the DPRK's relations with Pakistan especially due to its help for Pakistan's nuclear missile program. In 1999, India impounded a DPRK ship off the Kandla coast that was found to be carrying missile components and blueprints. India's relations with South Korea have far greater economic and technological depth and India's keenness for South Korean investments and technology have in turn affected the North's relations with India. India has consistently voiced its opposition to the DPRK's nuclear and missile tests.[183][184]

Trade between India and the DPRK has seen a large increase in recent years. From an average total trade of barely $100 million in the middle of the 2000s, it shot up to over $1 billion in 2009. The trade is overwhelmingly in India's favour, with its exports accounting for roughly $1 billion while the DPRK's exports to India were worth $57 million. India's primary export to the DPRK is refined petroleum products while silver and auto parts are the main components of its imports from the DPRK.[185] India participated in the sixth Pyongyang Autumn International Trade Fair in October 2010 and there have been efforts to bring about greater economic cooperation and trade between the two countries since then.[182][184] In 2010–11, Indo–DPRK trade stood at $572 million with India's exports accounting for $329 million. India has been providing training to the DPRK's citizens in areas like science and technology and IT through agreements for such cooperation between Indian and the DPRK's agencies and through India's International Technological and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) programme.[186][187]

In 2002 and 2004, India contributed 2000 tonnes of food grains to help the DPRK tide over severe famine-like conditions. In 2010, India responded to the DPRK's request for food aid and made available to it 1,300 tonnes of pulses and wheat worth $1 million through the UN World Food Programme.[188][189]

Indonesia

Indonesia maintains cordial relations with the DPRK, despite international sanctions and isolation applied upon the DPRK concerning its human rights abuses and nuclear missile program.[190] Both nations share a relationship that dates back to the Sukarno and Kim Il-sung era in the 60s. Indonesia has an embassy in Pyongyang, while the DPRK has an embassy in Jakarta, with cordial diplomatic relations.[191][192][193] Both nations are members of the Non-Aligned Movement, with broad support for the DPRK among the Indonesia populace, with a DPRK restaurant in the country currently.[194][195]

Iran

Iran–DPRK relations are described as being positive by official news agencies of the two countries. Diplomatic relations picked up following the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the establishment of an Islamic Republic. Iran and the DPRK pledged cooperation in educational, scientific, and cultural spheres,[196] as well as cooperating in the nuclear program of Iran.[197] The United States has expressed its opposition towards the DPRK's arms deals with Iran, which started during the 1980s during the Iran–Iraq War, as well as selling domestically produced weapons to Iran, with former U.S. President George W. Bush labelling the DPRK, Iran, and Iraq under Saddam Hussein as part of the "Axis of evil," in his conception.

Israel

Israeli–DPRK relations are hostile, and the DPRK does not recognise the state of Israel, denouncing it as an 'imperialist satellite'.[198] Since 1988 it recognises the sovereignty of the State of Palestine over the territory held by Israel.

Over the years, the DPRK has supplied missile technology to Israel's neighbours, including Iran, Syria, Libya, and Egypt.[199][200][201] Syria, which has a history of confrontations with Israel, has long maintained a relationship with the DPRK based on the cooperation between their respective nuclear programs. On 6 September 2007, the Israeli Air Force conducted an airstrike on a target in the Deir ez-Zor region of Syria. According to Media and IAEA investigative reports, 10 DPRK nuclear scientists were killed during the airstrike.[202]

When the DPRK opened up for Western tourists in 1986 it excluded citizens of Israel along with those of Japan, the United States, and South Africa.[203] It has been suggested that the DPRK has sought to model its nuclear weapons program on Israel's, as "a small-state deterrent for a country surrounded by powerful enemies; to display enough activity to make possession of a nuclear device plausible to the outside world, but with no announcement of possession: in short, to appear to arm itself with an ultimate trump card and keep everyone guessing whether and when the weapons might become available."[204]

Italy

While the DPRK was considered isolationist and "politically reclusive" by the Italian government for years, in January 2000, Italy announced its opening of official diplomatic relations with the DPRK.[205][206][207] Later, the DPRK's representative for the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization met with Lamberto Dini to formally establish diplomatic ties, with formal ties considered a huge step for the DPRK.[208]

Japan

Japan, along with South Korea, Taiwan, France and the United States, is one of the few countries that has no relations with the DPRK.

However, numerous groups within Japan support the DPRK. In May 2017, a delegation of officials from the Korean Youth League visited the birthplace of Kim Il Sung in Mangyongdae, touring the Mangyongdae Revolutionary Museum, the Korean Revolution Museum, the Mangyongdae Schoolchildren's Palace, and so on as part of their visit.[209]

Laos

Laos maintains an embassy in Pyongyang, with Laos being a similar state ideologically.[210] In February 2016 Kim Yong-Chul made an official visit to Bounnhang Vorachith

Libya

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Libyan government lead by Libyan Dictator Muammar Gaddafi established close ties with the DPRK Regime and purchased a significant amount of the DPRK's weaponry.[211] In 2015, it was estimated that 300 to 400 DPRK citizens were living in Libya.

Madagascar

The DPRK has been an ally of Madagascar since the 1970s. The DPRK provided assistance in construction projects, such as building the Iavoloha Palace.[212] In 1976, Madagascar hosted a conference on the Juche concept, an established part of the DPRK's foreign policy.[213]

Malaysia

The DPRK maintained friendly diplomatic ties with Malaysia, with an embassy in Kuala Lumpur while Malaysia had an embassy in Pyongyang.[214][215] In an effort to boost tourism between the two countries, the DPRK announced that Malaysians will not require a visa to visit the DPRK.[216]

After the assassination of Kim Jong-nam, relations between both countries steadily worsened, and as a response Malaysia gradually withdrew its ambassador from the DPRK, cancelled the visa-free entry for the DPRK for security reasons, and decided to expel the DPRK's ambassador. The ambassador of North Korea has been declared by Malaysia as Persona non grata.[217][218][219] However, both countries still retain their diplomatic ties.[220][221]

Malta

During the Cold War, Malta had good relations with the DPRK. The future leader Kim Jong-il spent a year there learning English in 1973. The Maltese Prime Minister Dom Mintoff traveled to Pyongyang to meet President Kim Il-sung in 1982. They signed a secret military agreement whereby the DPRK supplied Malta with weapons and military training. In 1984, Malta severed ties with South Korea.[222]

Mauritania

The DPRK and Mauritania established relations in 1964. President Moktar Ould Daddah visited Pyongyang in 1967, while Kim Il-sung went to Mauritania in 1975. Relations soured shortly afterwards when the DPRK recognised the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. In 2017, a DPRK delegation visited Mauritania, and the two governments pledged to increase co-operation.[223]

Mexico

Both nations established diplomatic relations on 4 September 1980.

- Mexico is accredited to North Korea from its embassy in Seoul, South Korea.[224]

- North Korea has an embassy in Mexico City.[225]

On September 7, 2017, Mexico expelled its North Korean ambassador as punishment for Pyongyang's nuclear tests in 2017.[226] However, ties between the two countries have not yet been officially broken.[227]

Mongolia

DPRK–Mongolia relations date back to 1948, when the Mongolian People's Republic recognized Kim Il-sung's Soviet-backed government in the North. Mongolia also provided assistance to the North during the Korean War. The two countries signed their first friendship and cooperation treaty in 1986.[228] Kim Il-sung also paid a visit to the country in 1988.[229] However, relations became strained after the collapse of the Communist government in Mongolia between 1989 and 1991. The two countries nullified their earlier friendship and cooperation treaty in 1995, and in 1999, the DPRK closed its embassy in Ulaanbaatar during an official visit by Kim Dae-jung, the first-ever such visit by a South Korean president.[228] Mongolia had previously expelled two DPRK diplomats but later pursued a policy of engagement.[230][231]

Mozambique

Mozambique has a history of good relations with the DPRK. Its capital Maputo has a street called Avenida Kim Il Sung after the founder of North Korea.[232] In 2016 a delegation of the Mozambique Liberation Front visited Pyongyang and met with members of the Workers' Party of Korea.[233]

Myanmar

Myanmar (Burma) and North Korea established bilateral diplomatic relations in May 1975.[234] The history of contacts between the two countries goes back to 1948, the year of the declaration of Burmese independence. Initially, however, Burma under U Nu favored Syngman Rhee's government in the South of Korea.[235] During and after the Korean War, Burma balanced the interest of North and South Korea, taking into consideration the position of China.[236] After the 1975 establishment of diplomatic relations Burma began to shift toward North Korea, which was also nominally socialist and equally wary of both US and Chinese imperialism.[237]

The Rangoon bombing on 9 October 1983 was a turning point in Myanmar–North Korea relations. Once it found out that North Koreans were behind the attack, Myanmar cut off diplomatic relations and went as far as withdrawing formal recognition of the country.[238] Relations began to recover during the years of the Sunshine Policy when South Korea encouraged the North's rapprochement with Myanmar.[239] Strategic considerations brought Myanmar and North Korea even closer. Burma had natural resources that North Korea needed, and North Korea began supplying Myanmar with military technology.[240] Diplomatic relations were restored on 25 April 2007.[241]

Military cooperation between North Korea and Myanmar deepened into cooperation with nuclear issues. Myanmar is believed to operate a nuclear weapons program that seeks to emulate the success of North Korea's nuclear weapons capability.[242] The program is supported by North Korean training and equipment. Although the 2011–2015 Myanmar political reforms have led to the cancellation or downgrading of military ties,[243] reports on suspicious activities have continued as of 2018.[244]

Namibia

Namibia's ruling party, the South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO) has had a longstanding historical relationship with North Korea, dating back to the South African Border War.[245][246][247][248] Beginning in 1964, North Korea provided training and arms to SWAPO's armed wing, the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), which was engaged in an insurgency against the South African government.[249][250] Following Namibian independence, North Korea established an embassy in Windhoek; however, the current status of the embassy remains unclear.[251]

Kim Yong-nam, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme People's Assembly, visited Namibia in 2008, and several bilateral agreements have been signed. The DPRK has helped build state houses in the regions within the country, and military co-operation continues even with sanctions on the DPRK.[252][253][254][255][256]

Netherlands

The Netherlands and the DPRK have maintained diplomatic relations since 2001. In 2011, the two countries celebrated 10 years of diplomatic relations, and for the occasion the DPRK showed three Dutch documentaries in Pyongyang, including one about Dutch water management. Contact with the DPRK are maintained by the Dutch ambassador in Seoul, South Korea. The DPRK's embassy in Bern, Switzerland serves the DPRK's interests in the Netherlands. The Netherlands is worried about the violations of human rights and the development of nuclear technologies in the DPRK, and has urged the DPRK to improve their bilateral relations with South Korea.[257]

There is little economic interest between the two countries. The most recent data about trade between the two countries dates back to 2011, and showed a decline.

While the Netherlands does not have a bilateral development relationship with the DPRK, it does participate in several humanitarian projects through the UN, EU and the International Red Cross. In addition, Wageningen University and Research Centre and the Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Pyongyang are working together on several projects concerning food safety and recent developments in potato farming.

New Zealand

Relations between the two countries have been almost non-existent since the establishment of the DPRK. During the 1950s, New Zealand fought against the DPRK in the Korean War, siding with the United States and South Korea. Since then, New Zealand had little contact with the DPRK until 2001, when the New Zealand's Foreign Affairs Minister Phil Goff met with his DPRK counterpart Paek Nam-sun. Diplomatic relations were established shortly thereafter. New Zealand has accredited its embassy in South Korea to the DPRK as well.[258] New Zealand Ambassador Patrick Rata is in charge of New Zealand's relations with both South and the DPRK.[259] New Zealand's Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters made a trip to Pyongyang on November 20, 2007. The Foreign Affairs Minister had talks with President Kim Yong-nam in his two-day visit to the DPRK's capital. Areas in which New Zealand is looking to co-operate could include agriculture, training, and conservation.

Nigeria

Nigeria and the DPRK established diplomatic relations in 1976. In 2014, they signed an agreement to facilitate the exchange of information about technology, including exchanges and joint projects between universities. The DPRK also proposed that Nigeria become a permanent member of the UN Security Council.[260]

Pakistan

Pakistan maintains warm diplomatic and trade relations with the DPRK, while still maintaining friendly relations with South Korea. The start of relations between the two countries emerged sometime in the 1970s during the rule of Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. The DPRK maintains an embassy in Islamabad. Relations between the two countries are reported to have been strong in the past and the DPRK has supplied missile technology to Pakistan even as the populace of Pakistan is divided on the DPRK.[194][261][262][263]

Palestine

The DPRK established diplomatic relations with Palestine in 1966.[11] Beyond this, the DPRK has long seen Israel as an "imperialist satellite" and recognizes the sovereignty of Palestine over all territory held by Israel, excluding the Golan Heights, which is considered as Syrian Territory.[198] After the demise of the Soviet Union, the DPRK's in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict declined and the DPRK shifted from the exporting of revolution to pragmatism.[264] During the Gaza War (2008–09) the DPRK harshly condemned Israeli actions, with a Foreign Ministry spokesman denounced the killing of unarmed civilians and called it a crime against humanity.[265] Later, on the floor of the UN General Assembly the DPRK permanent representative Sin Son-ho said that the DPRK "fully supported Palestinians' struggle to expel Israeli aggressors from their Territory and restore their right to self-determination."[266] After the 2010 Gaza flotilla raid the DPRK Foreign Ministry called the attack a "crime against humanity" perpetrated under the guidance of the United States, with the DPRK also expressing full support for the self-determination of the Palestinian Arabs.[267] During the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict, the Foreign Ministry issued a statement that read: "We bitterly denounce Israel's brutal killings of many defenseless Palestinians through indiscriminate military attacks on peaceable residential areas in Palestine as they are unpardonable crimes against humanity."[268]

Peru

The DPRK and Peru established diplomatic relations in 1988, with the DPRK with an embassy in Lima, Peru.[269] Even so, the Peruvian government condemned the "third nuclear test" by the DPRK in 2013, saying "the government of Peru calls on the government of North Korea to immediately stop these types of actions."[270]

In September 2017, Peru expelled ambassadors of the North Korea, meaning that relations between countries has been expired.[271]

Philippines

In 2000, the Philippines and the DPRK established diplomatic relations after more than 20 years of negotiations. Trade between the two countries remains almost non-existent as a trade embargo remains in place. In 2007, the agreement was boosted further and was signed by Philippine Foreign Secretary Alberto Romulo and DPRK Foreign Minister Pak Ui Chun during the Association of South-east Asian Nations (ASEAN) meeting in Manila.[272] The Philippines has a representative in Pyongyang through an embassy in Beijing. DPRK has a representative through its embassy in Bangkok.

Poland

Poland maintains diplomatic and limited trading (fishing) relations with the DPRK after relations between the two countries began on 16 October 1948. Poland maintains an embassy in Pyongyang, with economic relations between the two countries currently maintained at the symbolic level of trade and sailing co-operation[273][274][275]

Portugal

Kim Yong-nam has made statements affirming the good relationship between the two countries, such as the condolences he gave then-President Jorge Sampaio when Francisco da Costa Gomes died,[276] and the congratulations he extended to President Cavaco Silva after he won the Portuguese elections.[277] In 2017, Portugal cuts diplomatic ties with North Korea.[278]

Romania

Socialist Republic of Romania and North Korea established diplomatic relations on 3 November 1948.[11] Nicolae Ceaușescu and Kim Il-sung met in 1971 as part of Ceaușescu's Asian tour.[279] The two were close allies,[14] and got along both in terms of political and personal relations.[280] During the trip, Ceausescu took a liking to North Korea's Juche ideology. This experience contributed to his formerly liberal stance taking a turn for authoritarianism.[279] It the first of many times Ceaușescu would visit Pyongyang.[281]

Both countries host embassies to one another.[82]

Russia

Russia–DPRK relations are determined by Russia's strategic interests in Korea and the goal of preserving peace and stability in the Korean peninsula. Russia's official position is by extension its stance on settlement of the North Korean nuclear crisis.

Senegal

Senegal and the DPRK have had diplomatic relations since 1972.[282] The African Renaissance Monument in Dakar, Senegal, was built by Mansudae Overseas Projects, a company from the DPRK.[283]

Seychelles

During the 1977–2004 rule of President France-Albert René, the socialist and non-aligned government of Seychelles maintained close relations with the DPRK, receiving significant DPRK developmental aid.[284]

Serbia

Serbia maintains friendly relations with the DPRK, with relations between the two countries started in 1948 under the Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito. In March 2017, North Korean Ambassador Ri Pyong Du visited Belgrade and affirmed North Korea's support of Serbia's position on Kosovo.[285]

Singapore

Singapore and the DPRK have extremely good relations. Numerous Singaporean companies have opened up businesses in Pyongyang, the country's capital. Singapore is also the DPRK's 4th largest trade partner (after Russia, China, and Malaysia). DPRK citizens can visit Singapore by applying for an e-visa online. The DPRK maintains an embassy in Singapore while the latter has accredited a non-resident ambassador in Beijing to the DPRK.[286]

Slovenia

Slovenia and the DPRK have a bilateral relation that began in 1948, during the time of Yugoslavia.

Somalia

Diplomatic relations between the DPRK and Somalia were formally established on 13 April 1967. This late-1950s to 1960s period was when the DPRK had first declared autonomous diplomacy.[11] However, to this day the DPRK favours Ethiopia rather than Somalia during the Ethio-Somali conflict.

South Africa

The DPRK supported the African National Congress in its struggle against apartheid in South Africa. The DPRK campaigned against the white minority government and provided military training to ANC fighters in camps in Angola. In 1998, after the end of apartheid, the DPRK and South Africa established diplomatic relations. A DPRK embassy was established in Pretoria. The two governments continue to have friendly relations.[17]

South Sudan

DPRK and South Sudan established diplomatic relations in November 2011, shortly after South Sudan gained independence from Sudan.[287]

Spain

In January 2014, the DPRK opened an embassy in Madrid.[288] Following a series of nuclear and missile tests by North Korea in 2017, Spain declared the North Korean ambassador, Kim Hyok Chol, persona non grata on September 18.[289]

Sri Lanka

In 1970, the DPRK trade delegation's office in Colombo became an embassy. While in the country, the DPRK diplomats cultivated links with the Marxist–Leninist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna. In 1971, in the wake of a failed uprising by the JVP, embassy was closed.[290]

Sweden

Sweden was the first Western country to open an embassy in the DPRK. The embassy is located in Pyongyang, and "Sweden serves as the interim consular protecting power for American, Finnish, Australian and Canadian interests in North Korea."[291] The Swedish-Korean Association has friendly ties with the DPRK government and works to promote solidarity with and support for it.

Switzerland

Switzerland is an active member of the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC), an international organization for the prevention of hostilities on the Korean peninsula. Switzerland conducts regular political dialogue with the DPRK, the last meeting taking place in October 2011. North Korea maintains both an embassy in Bern and a permanent mission in Geneva. Switzerland's embassy in Beijing is accredited to Pyongyang but the Swiss also have a permanent office for Development and Cooperation in North Korea, responsible for humanitarian aid.[292]

Cooperation in the domaine of education was maintained but North Korea's interest to work closer with Swiss companies has been put on hold since May 2016, when the Swiss cabinet introduced "considerably tighter sanctions" to slow down North Korea's nuclear proliferation.[293] In the aftermath of North Korea's nuclear weapons test on September 3, 2017, Swiss Federal Councilor and President Doris Leuthard emphasized the need for renewed negotiations, and offered pertinent mediation services between the United States and North Korea.[294]

Syria

Syria and the DPRK have had close relations since the late 1960s, when the DPRK provided military assistance to Syria in its wars with Israel.[295] They maintain embassies in the other country's respective capitals.[296]

The DPRK built a nuclear reactor in Syria based on the design of its own reactor at Yongbyon, and DPRK officials traveled regularly to the site. The Syrian reactor was destroyed by Israel in an airstrike in 2007.[297] The United States signed the Iran North Korea Syria Nonproliferation Act in 2000. In 2016, there were reports that DPRK troops were fighting to defend the Syrian government in the Syrian Civil War.[295]

Taiwan

The Republic of China (Taiwan) does not recognise North Korea as a state.

Taiwanese Premier Lai Ching-te approved a total ban on trade between Taiwan and North Korea in September 2017.[298] Taiwanese businessmen have been accused of selling coal, oil and gas to North Korea, as well as importing North Korean textiles and employing North Koreans in Taiwanese fishing vessels.[298]

Tanzania

Tanzania and the DPRK have a long history of military cooperation, going back to their mutual support for anti-imperialist struggle in southern Africa during the Cold War.[299] In 2016, there were 11 DPRK medical clinics operating in Tanzania, two others having recently been shut down by the government.[300] In 2017, it was reported that Tanzania was planning to open a general hospital employing dozens of DPRK doctors.[301]

Turkey

Turkey did not have any diplomatic relations with DPRK before 2001. In a statement made in 2001 in Beijing (China) by the Turkish and DPRK embassies, Turkey officially recognized the DPRK and on 15 January 2001 both countries established diplomatic relations.[302] Turkey is represented in the DPRK through its embassy in Seoul, South Korea. The DPRK is represented in Turkey through its embassy in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Turkey fought against North Korea during the Korean War, in which approximately 487 Turkish soldiers died.[303] In June 2018, Turkey and North Korea began negotiations to return the remains of deceased Turkish soldiers.[303]

Uganda

Uganda is a long-term ally of the DPRK. Yoweri Museveni, Uganda's president since 1986, has said that he learned basic Korean from Kim Il-sung during visits to North Korea.[232] The DPRK has provided training for pilots, technicians, police, marine forces, and special forces. In 2016 Uganda stated that it was ending this co-operation due to United Nations sanctions against the DPRK's nuclear weapons program. Uganda indicated, however, that it still considered the DPRK to be a friend.[304][305]

United Kingdom

Following initial progress in North Korea–South Korea relations, the DPRK and the United Kingdom established diplomatic relations on 12 December 2000, opening resident embassies in London and Pyongyang. The United Kingdom provides English language and human rights training to DPRK officials, urging the DPRK government to allow a visit by the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights, and it oversees bilateral humanitarian projects in the DPRK.[306][307]

To mark the tenth anniversary of the DPRK's relations with the United Kingdom, an edited version of the 2002 film Bend It Like Beckham was broadcast on DPRK state television on 26 December 2010. The British Ambassador to South Korea, Martin Uden, posted on Twitter that it was the "1st ever Western-made film to air on TV" in the DPRK.[308]

Good relations between the two nations have been in existence as far back as 1966 when the DPRK football team played in the 1966 World Cup in England. The DPRK team became the adopted team of Middlesbrough which was where they played their group games during the competition. Middlesbrough fans went on to support the DPRK team in the next round of the tournament, with many travelling to Liverpool to watch the team against Portugal. In 2002, members of the DPRK team returned to Middlesbrough for an official visit.[309]

United States

Though strained for more than half a century, relations have started to be mended between the United States and the DPRK under leaders Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un.

Prior to 2018, relations developed primarily during the Korean War, but in recent years have been largely defined by the DPRK's six tests of nuclear weapons, its development of long-range missiles capable of striking targets thousands of miles away, and its ongoing threats to strike the United States[310] and South Korea with nuclear weapons and conventional forces.[311][312]

Although hostility between the two countries has its roots in Cold War politics, earlier conflicts between the United States and Korea included the 19th-century General Sherman Incident, when Korean forces attacked a U.S. gunboat sent to negotiate a trade treaty and killed its crew, after it defied instructions from Korean officials. A retaliatory U.S. attack followed, called the Sinmiyangyo in Korean.

On March 8, 2018, South Korean diplomat Chung Eui-yong announced that President Trump would meet Chairman Kim before the end of May in an effort to achieve "permanent denuclearisation".[313] North Korean leader Kim Jong Un agrees to destroy its nuclear test site fully in the presence of the International Media before USA President Donald Trump scheduled to meet him at Singapore on 12 June 2018.[314] Eventually, the leaders shook hands and held discussions at the Capella Hotel in Sentosa Island, Singapore on the originally scheduled date of 12 June 2018.

Venezuela

North Korea have a very friendly relationship after Hugo Chavez took power. In 2008, president Hugo Chávez planned to visit North Korean leader, Kim Jong Il in Pyongyang.[315] In 2015,North Korea reopened it's embassy in La Mercedes, Caracas as solidarity between Caracas and Pyongyang has strengthened. The two countries also signed a bilateral agreement to build a giant statue.[316]

Vietnam

Students from North Vietnam began going to the DPRK to study as early as the 1960s, even before the formal establishment of Korean-language education in their country.[317]

North Korea lent material and manpower support to North Vietnam during the Vietnam War, though the number of South Korean troops fighting for South Vietnam was larger.[318][319] As a result of a decision of the Korean Workers' Party in October 1966, in early 1967 the DPRK sent a fighter squadron to North Vietnam to back up the North Vietnamese 921st and 923rd fighter squadrons defending Hanoi. They stayed through 1968; 200 pilots were reported to have served.[319] In addition, at least two anti-aircraft artillery regiments were sent as well. The DPRK also sent weapons, ammunition and two million sets of uniforms to their comrades in North Vietnam.[320] Kim Il-sung is reported to have told his pilots to "fight in the war as if the Vietnamese sky were their own".[321][322][323]

Zimbabwe

The relationship between the DPRK and Zimbabwe goes back to the struggle for independence. Soldiers of Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwean African National Liberation Army were trained in the DPRK in the 1970s.[17] In 1980, after independence was gained, the new Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe visited the DPRK. In October 1980, Kim Il-sung and Mugabe signed an agreement for an exchange of soldiers. Following this agreement, 106 DPRK soldiers arrived in Zimbabwe to train a brigade of soldiers that became known as the Fifth Brigade. Zimbabwe's governing party, the ZANU-PF, mourned the death of DPRK leader Kim Jong-il in 2011. In 2013, the two countries signed an agreement, exchanging Zimbabwean uranium for DPRK arms.[324]

International organizations

The DPRK is a member of the following international organizations:[325]

- ASEAN Regional Forum[326]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- Group of 77

- International Civil Aviation Organization

- International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement

- International Fund for Agricultural Development

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

- International Hydrographic Organization

- International Maritime Organization

- International Olympic Committee

- International Organization for Standardization

- International Telecommunications Satellite Organization

- International Telecommunication Union

- Inter-Parliamentary Union

- Non-Aligned Movement

- United Nations

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization

- World Tourism Organization

- Universal Postal Union

- World Federation of Trade Unions

- World Health Organization

- World Intellectual Property Organization[327]

- World Meteorological Organization

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-05-06. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ↑ United Nations, "North Korean Constitution", April 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Naenara, "Socialist Constitution of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea," Pyongyang, Korea, Juche 103 (2014).

- ↑ Past news Archived 2006-01-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sometimes, the announcements never mention what sort of gift, but the Kim family has a large collection of cultural and other souvenirs from leaders all over the world, which is partly or entirely on public display.

- ↑ Perlez, Jane (2000-10-25). "Albright reports progress in talks with north korea". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ↑ "North Korea threatens "sea of fire" if attacked". BBC. 1999-01-22. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ Dagyum Ji (17 January 2017). "Document details the heavy restrictions on diplomats in North Korea". NK News. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- 1 2 "Q&A: China-North Korea Relationship" Archived 2017-02-17 at the Wayback Machine., New York Times, July 13, 2006

- 1 2 Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance between the People's Republic of China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea Archived 2013-01-22 at the Wayback Machine., 11 July 1967.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wertz, Oh & Kim 2016, p. 3.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 76. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Schaefer, Bernd (8 May 2017). "North Korea and the East German Stasi, 1987–1989". Wilson Center.

- 1 2 Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 113. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Young, Benjamin (30 March 2015). "Juche in the United States: The Black Panther Party's Relations with North Korea, 1969–1971". The Asia Pacific Journal. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016.

- ↑ Farrell, Tom (17 May 2013). "Rocky road to Pyongyang: DPRK-IRA relations in the 1980s". NK News. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Young, Benjamin R (16 December 2013). "North Korea: Opponents of Apartheid". NK News. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016.

- ↑ Armstrong, Charles (April 2009). "Juche and North Korea's Global_Aspirations" (PDF). NKIDP Working Paper (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-07.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 36–37. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-415-23749-9.

- ↑ Barry K. Gills, Korea versus Korea: A Case of Contested Legitimacy (Routledge, 1996), p. 198.

- ↑ Time Magazine "A Bomb Wreaks Havoc in Rangoon," 17 Oct, 1983.