Korean Demilitarized Zone

| Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) | |

|---|---|

|

한반도 비무장 지대 韓半島非武裝地帶 Hanbando Bimujang jidae | |

| Korean Peninsula | |

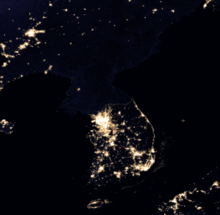

A South Korean checkpoint at the Civilian Control Line, located outside of the DMZ | |

The Korean DMZ denoted by the red highlighted area. The blue line indicates the international border. | |

| Type | DMZ |

| Length | 250 kilometres (160 mi) |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | No; access only granted by the South Korean government. |

| Condition | Fully manned and operational |

| Site history | |

| Built by | |

| In use | since 27 July 1953 |

| Events | Division of Korea |

The Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ; Chosŏn'gŭl/Hangul: 한반도 비무장 지대; Hanja: 韓半島非武裝地帶) is a strip of land running across the Korean Peninsula. It is established by the provisions of the Korean Armistice Agreement to serve as a buffer zone between North Korea and South Korea. The demilitarized zone (DMZ) is a border barrier that divides the Korean Peninsula roughly in half. It was created by agreement between North Korea, China and the United Nations in 1953. The DMZ is 250 kilometres (160 miles) long, and about 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) wide.

Within the DMZ is a meeting point between the two nations in the small Joint Security Area (JSA) near the western end of the zone, where negotiations take place. There have been various incidents in and around the DMZ, with military and civilian casualties on both sides.

Location

The Korean Demilitarized Zone intersects but does not follow the 38th parallel north, which was the border before the Korean War. It crosses the parallel on an angle, with the west end of the DMZ lying south of the parallel and the east end lying north of it.

The DMZ is 250 kilometres (160 miles) long,[1] approximately 4 km (2.5 mi) wide. Though the zone separating both sides is demilitarized, beyond that strip the border is one of the most heavily militarized borders in the world.[2] The Northern Limit Line, or NLL, is the disputed maritime demarcation line between North and South Korea in the Yellow Sea, not agreed in the armistice. The coastline and islands on both sides of the NLL are also heavily militarized.[3]

History

The 38th parallel north—which divides the Korean Peninsula roughly in half—was the original boundary between the United States and Soviet Union's brief administration areas of Korea at the end of World War II. Upon the creation of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK, informally North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (ROK, informally South Korea) in 1948, it became a de facto international border and one of the most tense fronts in the Cold War.

Both the North and the South remained dependent on their sponsor states from 1948 to the outbreak of the Korean War. That conflict, which claimed over three million lives and divided the Korean Peninsula along ideological lines, commenced on 25 June 1950, with a full-front DPRK invasion across the 38th parallel, and ended in 1953 after international intervention pushed the front of the war back to near the 38th parallel.

In the Armistice Agreement of 27 July 1953, the DMZ was created as each side agreed to move their troops back 2,000 m (2,200 yards) from the front line, creating a buffer zone 4 km (2.5 mi) wide. The Military Demarcation Line (MDL) goes through the center of the DMZ and indicates where the front was when the agreement was signed.

Owing to this theoretical stalemate, and genuine hostility between the North and the South, large numbers of troops are still stationed along both sides of the line, each side guarding against potential aggression from the other side. The armistice agreement explains exactly how many military personnel and what kind of weapons are allowed in the DMZ. Soldiers from both sides may patrol inside the DMZ, but they may not cross the MDL; ROK soldiers, however heavily armed, patrol under the aegis of military police, and have memorized each line of the armistice.[4] Sporadic outbreaks of violence have killed over 500 South Korean soldiers, 50 US soldiers and 250 soldiers from DPRK along the DMZ between 1953 and 1999.[5]

Daeseong-dong (also written Tae Sung Dong) and Kijŏng-dong are the only settlements allowed by the armistice committee to remain within the boundaries of the DMZ.[6] Residents of Tae Sung Dong are governed and protected by the United Nations Command and are generally required to spend at least 240 nights per year in the village to maintain their residency.[6] In 2008, the village had a population of 218 people.[6] The villagers of Tae Sung Dong are direct descendants of people who owned the land before the 1950–53 Korean War.[7]

To continue to deter North Korean incursion, in 2014 the United States government exempted the Korean DMZ from its pledge to eliminate anti-personnel landmines.[8] On October 1, 2018, however, a 20-day process began to remove landmines from both sides of the DMZ.[9]

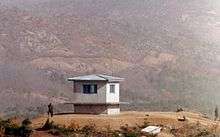

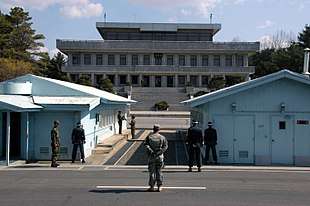

Joint Security Area

Inside the DMZ, near the western coast of the peninsula, Panmunjom is the home of the Joint Security Area (JSA). Originally, it was the only connection between North and South Korea[10] but that changed on 17 May 2007, when a Korail train went through the DMZ to the North on the new Donghae Bukbu Line built on the east coast of Korea. However, the resurrection of this line was short-lived, as it closed again in July 2008 following an incident in which a South Korean tourist was shot and killed.

There are several buildings on both the north and the south side of the Military Demarcation Line (MDL), and there have been some built on top of it. The JSA is the location where all negotiations since 1953 have been held, including statements of Korean solidarity, which have generally amounted to little except a slight decline of tensions. The MDL goes through the conference rooms and down the middle of the conference tables where the North Koreans and the United Nations Command (primarily South Koreans and Americans) meet face to face.

Within the JSA are a number of buildings for joint meetings called Conference Rooms. These are used for direct talks between the Korean War participants and parties to the armistice. Facing the Conference Row buildings are the North Korean Panmungak (English: Panmun Hall) and the South Korean Freedom House. In 1994, North Korea enlarged Panmungak by adding a third floor. In 1998, South Korea built a new Freedom House for its Red Cross staff and to possibly host reunions of families separated by the Korean War. The new building incorporated the old Freedom House Pagoda within its design.

Since 1953 there have been occasional confrontations and skirmishes within the JSA. The axe murder incident in August 1976 involved the attempted trimming of a tree which resulted in two deaths (Captain Arthur Bonifas and First Lieutenant Mark Barrett). Another incident occurred on 23 November 1984, when a Soviet tourist named Vasily Matuzok (sometimes spelled Matusak), who was part of an official trip to the JSA (hosted by the North), ran across the MDL shouting that he wanted to defect.[11] North Korean troops immediately chased after him, opening fire. Border guards on the South Korean side returned fire, eventually surrounding the North Koreans as they pursued Matusak. One South Korean and three North Korean soldiers were killed in the action, and Matusak was not captured.[12]

In late 2009, South Korean forces in conjunction with the United Nations Command began renovation of its three guard posts and two checkpoint buildings within the JSA compound. Construction was designed to enlarge and modernize the structures. Work was undertaken a year after North Korea finished replacing four JSA guard posts on its side of the MDL.[13]

Villages

Both North and South Korea maintain peace villages in sight of each other's side of the DMZ. In the South, Daeseong-dong is administered under the terms of the DMZ. Villagers are classed as Republic of Korea citizens, but are exempt from paying tax and other civic requirements such as military service. In the North, Kijŏng-dong features a number of brightly painted, poured-concrete multi-story buildings and apartments with electric lighting. These features represented an unheard-of level of luxury for rural Koreans, north or south, in the 1950s. The town was oriented so that the bright blue roofs and white sides of the buildings would be the most distinguishing features when viewed from the border. However, based on scrutiny with modern telescopic lenses, it has been claimed the buildings are mere concrete shells lacking window glass or even interior rooms,[14][15] with the building lights turned on and off at set times and the empty sidewalks swept by a skeleton crew of caretakers in an effort to preserve the illusion of activity.[16]

Flagpoles

In the 1980s, the South Korean government built a 98.4 m (323 ft) flagpole in Daeseong-dong, which flies a South Korean flag weighing 130 kilograms (287 pounds). In what some have called the "flagpole war," the North Korean government responded by building the 160 m (525 ft) Panmunjeom flagpole in Kijŏng-dong, only 1.2 km (0.7 mi) west of the border with South Korea. It flies a 270 kg (595 lb) flag of North Korea. As of 2014, the Panmunjom flagpole is the fourth tallest in the world, after the Jeddah Flagpole in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, at 170 m (558 ft), the Dushanbe Flagpole in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, at 165 m (541 ft) and the pole at the National Flag Square in Baku, Azerbaijan, which is 162 m (531 ft).[17][18]

DMZ-related incidents and incursions

Since demarcation, the DMZ has had numerous cases of incidents and incursions by both sides, although the North Korean government typically never acknowledges direct responsibility for any of these incidents (there are exceptions, such as the axe incident).[19] This was particularly intense during the Korean DMZ Conflict (1966–1969) when a series of skirmishes along the DMZ resulted in the deaths of 43 American, 299 South Korean and 397 North Korean soldiers.[20] This included the Blue House Raid in 1968, an attempt to assassinate President Park Chung Hee at the Blue House.[21]

In 1976, in now-declassified meeting minutes, U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense William Clements told Henry Kissinger that there had been 200 raids or incursions into North Korea from the south, though not by the U.S. military.[22] Details of only a few of these incursions have become public, including raids by South Korean forces in 1967 that had sabotaged about 50 North Korean facilities.[23]

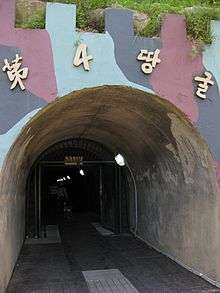

Incursion tunnels

Since 15 November 1974, South Korea has discovered four tunnels crossing the DMZ that had been dug by North Korea; the orientation of the blasting lines within each tunnel indicated they were dug by North Korea. North Korea claimed that the tunnels were for coal mining; however, no coal was found in the tunnels, which were dug through granite. Some of the tunnel walls were painted black to give the appearance of anthracite.[24]

The tunnels are believed to have been planned as a military invasion route by North Korea. They run in a north-south direction and do not have branches. Following each discovery, engineering within the tunnels has become progressively more advanced. For example, the third tunnel sloped slightly upwards as it progressed southward, to prevent water stagnation. Today, visitors from the south may visit the second, third and fourth tunnels through guided tours.[25]

First tunnel

The first of the tunnels was discovered on 20 November 1974, by a South Korean Army patrol, noticing steam rising from the ground. The initial discovery was met with automatic fire from North Korean soldiers. Five days later, during a subsequent exploration of this tunnel, US Navy Commander Robert M. Ballinger and ROK Marine Corps Major Kim Hah-chul were killed in the tunnel by a North Korean explosive device. The blast also wounded five Americans and one South Korean from the United Nations Command.

The tunnel, which was about 0.9 by 1.2 m (3 by 4 ft), extended more than 1 km (0.62 mi) beyond the MDL into South Korea. The tunnel was reinforced with concrete slabs and had electric power and lighting. There were weapon storage and sleeping areas. A narrow-gauge railway with carts had also been installed. Estimates based on the tunnel's size suggest it would have allowed considerable numbers of soldiers to pass through it.[26]

Second tunnel

The second tunnel was discovered on 19 March 1975. It is of similar length to the first tunnel. It is located between 50 and 160 m (160 and 520 ft) below ground, but is larger than the first, approximately 2 by 2 m (7 by 7 feet).

Third tunnel

The third tunnel was discovered on 17 October 1978. Unlike the previous two, the third tunnel was discovered following a tip from a North Korean defector. This tunnel is about 1,600 m (5,200 ft) long and about 73 m (240 ft) below ground.[27] Foreign visitors touring the South Korean DMZ may view inside this tunnel using a sloped access shaft.

Fourth tunnel

A fourth tunnel was discovered on 3 March 1990, north of Haean town in the former Punchbowl battlefield. The tunnel's dimensions are 2 by 2 m (7 by 7 feet), and it is 145 metres (476 ft) deep. The method of construction is almost identical in structure to the second and the third tunnels.[28]

Korean Wall

According to North Korea, between 1977 and 1979 the South Korean and United States authorities constructed a concrete wall along the DMZ.[29] North Korea, however, began to propagate information about the wall after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, when the symbolism of a wall unjustly dividing a people became more apparent.[30]

Various organisations, such as the North Korean tour guide company Korea Konsult, claimed a wall was dividing Korea, saying that:

In the area south of the Military Demarcation Line, which cuts across Korea at its waist, there is a concrete wall which ... stretches more than 240 km (149 mi) from east to west, is 5–8 m (16–26 ft) high, 10–19 m (33–62 ft) thick at the bottom, and 3–7 m (10–23 ft) wide in the upper part. It is set with wire entanglements and dotted with gun embrasures, look-outs and varieties of military establishments.[31]

In December 1999, Chu Chang-jun, North Korea's ambassador to China, repeated claims that a "wall" divided Korea. He said the south side of the wall is packed with soil, which permits access to the top of the wall and makes it effectively invisible from the south side. He also claimed that it served as a bridgehead for any northward invasion.[32][33]

The United States and South Korea deny the wall's existence, although they do claim there are anti-tank barriers along some sections of the DMZ.[34]

In the RT documentary 10 Days in North Korea, the crew shot footage of a wall as seen from North Korea and described it as a "5 metre high wall stretching from east to west".[35] Dutch journalist and filmmaker Peter Tetteroo also shot footage of a barrier in 2001 which his North Korean guides said was the Korean Wall.[29]

A 2007 Reuters report revealed that there is no coast to coast wall located across the DMZ and that the pictures of a "wall" which have been used in North Korean propaganda have merely been pictures of concrete anti-tank barriers.[36] While 800,000 landmines mines were being removed in 2018, it was shown that the Joint Security Area along the Korean border was guarded by standard barbed wire.[37]

North Korean side of the DMZ

The North Korean side of the DMZ primarily serves to defend North Korea from invasion by South Korean forces. It also serves a similar function as the Berlin Wall and the inner German border did against its own citizens in the former East Germany in that it stops North Korean citizens from defecting to South Korea.[38][39]

From the armistice until 1972, approximately 7,700 South Korean soldiers and agents infiltrated North Korea to sabotage military bases and industrial areas.[40]

North Korea has thousands of artillery pieces near the DMZ. According to a 2018 article in The Economist, North Korea could bombard Seoul with over 10,000 rounds every minute.[41] Experts believe that 60 percent of its total artillery is positioned within a few kilometers of the DMZ acting as a deterrent against any South Korean invasion.

Propaganda

Loudspeaker installations

From 1953 until 2004 both sides broadcast audio propaganda across the DMZ.[42] Massive loudspeakers mounted on several of the buildings delivered DPRK propaganda broadcasts directed towards the south as well as propaganda radio broadcasts across the border.[14] In 2004, the North and South agreed to end the broadcasts.[42]

In August 2015, a border incident occurred where two South Korean soldiers were wounded after stepping on landmines that had allegedly been laid on the southern side of the DMZ by North Korean forces near an ROK guard post.[43][44] Both North Korea and South Korea then resumed broadcasting propaganda by loudspeaker.[45] After four days of negotiations, on August 25, 2015 South Korea agreed to discontinue the broadcasts following a statement from North Korea's government expressing "regret" for the landmine incident.[46]

On 8 January 2016, in response to North Korea's supposed successful testing of a hydrogen bomb, South Korea resumed broadcasts directed at the north.[47] On 15 April 2016, it was reported that the South Koreans purchased a new stereo system to combat the North's broadcasts.[48]

Balloons

Both North and South Korea have held balloon propaganda leaflet campaigns since the Korean War.[49]

In recent years, mainly South Korean non-governmental organizations have been involved in launching balloons targeted at the DMZ and beyond.[50] Due to the winds, the balloons tend to fall near the DMZ where there are mostly North Korean soldiers to see the leaflets.[51] As with the loudspeakers, balloon operations were mutually agreed to be halted between 2004 and 2010.[52] It has been assessed that the activists' balloons may contribute to the decay of remaining cooperation between the Korean governments,[53] and the DMZ has become more militarized in recent years.[54]

Many North Korean leaflets during the Cold War gave instructions and maps to help the targeted South Korean soldiers in defecting. One of the leaflets found on the DMZ included a map of Cho Dae-hum's route of defection to North Korea across the DMZ. In addition to using balloons as a means of delivery, North Koreans have also used rockets to send leaflets to the DMZ.[55]

Dismantling of Border Propaganda

On April 23, 2018, both North and South Korea officially cancelled their border propaganda broadcasts for the last time.[56] On May 1, 2018, the loudspeakers across the Korean border were dismantled.[57] Also on May 1, both sides committed to ending the balloon campaigns.[58] On May 5, 2018, an attempt by North Korean defectors to disperse more balloon propaganda across the border from South Korea was halted by the South Korean government.[59]

Civilian Control Line

The Civilian Control Line is a line that designates an additional buffer zone to the DMZ within a distance of 5 to 20 km from the Southern Limit Line of the DMZ. Its purpose is to limit and control the entrance of civilians into the area in order to protect and maintain the security of military facilities and operations near the DMZ. The commander of the 8th US Army ordered the creation of the CCL and it was activated and first became effective in February 1954.[60]

The buffer zone that falls south of the Southern Limit Line is called the Civilian Control Zone. Barbed wire fences and manned military guard posts mark the Civilian Control Line. The Civilian Control Zone is necessary for the military to monitor civilian travel to tourist destinations close to the Southern Limit Line of the DMZ like the discovered infiltration tunnels and tourist observatories. Usually when traveling within the Civilian Control Zone, South Korean soldiers accompany tourist buses and cars as armed guards to monitor the civilians as well as to protect them from North Korean intruders.

Right after the ceasefire, the Civilian Control Zone outside the DMZ encompassed 100 or so empty villages. The government implemented migration measures to attract settlers into the area. As a result, in 1983, when the area delineated by the Civilian Control Line was at its largest, a total of 39,725 residents in 8,799 households were living in the 81 villages located within the Civilian Control Zone.[61]

Most of the tourist and media photos of the "DMZ fence" are actually photos of the CCL fence. The actual DMZ fence on the Southern Limit Line is completely off-limits to everybody except soldiers and it is illegal to take pictures of the DMZ fence. The CCL fence acts more as a deterrent for South Korean civilians from getting too close to the dangerous DMZ and is also the final barrier for North Korean infiltrators if they get past the Southern Limit Line DMZ fence.[62]

Neutral Zone of the Han River Estuary

The whole estuary of the Han River is deemed a "Neutral Zone" and is off-limits to all civilian vessels and is treated like the rest of the DMZ. Only military vessels are allowed within this neutral zone.

According to the July 1953 Korean Armistice Agreement civil shipping was supposed to be permissible in the Han River estuary and allow Seoul to be connected to the Yellow Sea (West Sea) via the Han River.[63] However, both Koreas and the UNC failed to make this happen. The South Korean government ordered the construction of the Ara Canal to finally connect Seoul to the Yellow Sea (West Sea), which was completed in 2012. Seoul was effectively landlocked from the ocean until 2012. The biggest limitation of the Ara Canal is it is too narrow to handle any vessels except small tourist boats and recreational boats, so Seoul still cannot receive large commercial ships or passenger ships in its port.

In recent years Chinese fishing vessels have taken advantage of the tense situation in the Han River Estuary Neutral Zone and illegally fished in this area due to both the North Korean and South Korean navies never patrolling this area due to the fear of naval battles breaking out. This has led to firefights and sinkings of boats between Chinese fishermen and the South Korean Coast Guard.[64][65]

Castle of Gung Ye

Within the DMZ itself, in the town of Cheorwon, is the old capital of the kingdom of Taebong (901–918), a regional upstart that became Goryeo, the dynasty that ruled a united Korea from 918 to 1392.

Taebong was founded by the charismatic leader Gung Ye, a brilliant if tyrannical one-eyed ex-Buddhist monk. Rebelling against the kingdom of Silla, Korea's then ruling dynasty, he proclaimed the kingdom of Taebong—also called Later Goguryeo, in reference to the ancient kingdom of Goguryeo (37BC-668AD)—in 901, with himself as king. The kingdom consisted of much of central Korea, including areas around the DMZ. He placed his capital in Cheorwon, a mountainous region that was easily defensible (in the Korean War, this same region would earn the name "the Iron Triangle").

As a former Buddhist monk, Gung Ye actively promoted the religion of Buddhism and incorporated Buddhist ceremonies into the new kingdom. Even after Gung Ye was dethroned by his own generals and replaced by Wang Geon, the man who would rule over a united Korea as the first king of Goryeo, this Buddhist influence would continue, playing a major role in shaping the culture of medieval Korea.

As the ruins of Gung Ye's capital lie in the DMZ itself, visitors cannot see them. Moreover, excavation work and research have been hampered by political realities. In the future, inter-Korean peace may allow for proper archaeological studies to be conducted on the castle site and other historical sites within and underneath the DMZ.[66]

The ruins of the capital city of Taebong, the ruins of the castle of Gung Ye, and King Gung Ye's tomb all lie within the DMZ and are off-limits to everybody except soldiers who patrol the DMZ.[67]

Transportation

Panmunjeom is the site of the negotiations that ended the Korean War and is the main center of human activity in the DMZ. The village is located on the main highway and near a railroad connecting the two Koreas.

The railway, which connects Seoul and Pyongyang, was called the Gyeongui Line before division in the 1940s. Currently the South uses the original name, but the North refers to the route as the P'yŏngbu Line. The railway line has been mainly used to carry materials and South Korean workers to the Kaesong Industrial Region. Its reconnection has been seen as part of the general improvement in the relations between North and South in the early part of this century. However, in November 2008 North Korean authorities closed the railway amid growing tensions with the South.[68] Following the death of former South Korean President Kim Dae-jung, conciliatory talks were held between South Korean officials and a North Korean delegation who attended Kim's funeral. In September 2009, the Kaesong rail and road crossing was reopened.[69]

The road at Panmunjeom, which was known historically as Highway One in the South, was originally the only access point between the two countries on the Korean Peninsula. Passage is comparable to the strict movements that occurred at Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin at the height of the Cold War. Both North and South Korea's roads end in the JSA; the highways do not quite join as there is a 20 cm (8 in) concrete line that divides the entire site. People given the rare permission to cross this border must do so on foot before continuing their journey by road.

In 2007, on the east coast of Korea, the first train crossed the DMZ on the new Donghae Bukbu (Tonghae Pukpu) Line. The new rail crossing was built adjacent to the road which took South Koreans to Mount Kumgang Tourist Region, a region that has significant cultural importance for all Koreans. More than one million civilian visitors crossed the DMZ until the route was closed following the shooting of a 53-year-old South Korean tourist in July 2008.[70] After a joint investigation was rebuffed by North Korea, the South Korean government suspended tours to the resort. Since then the resort and the Donghae Bukbu Line have effectively been closed by North Korea.[71][72] Currently, the South Korean Korea Railroad Corporation (Korail) organizes tours to DMZ with special DMZ themed trains.[73]

Nature reserve

In the past half century, the Korean DMZ has been a deadly place for humans, making habitation impossible. Only around the village of Panmunjeom and more recently the Donghae Bukbu Line on Korea's east coast have there been regular incursions by people.[74][75]

This natural isolation along the 250 km (160 mi) length of the DMZ has created an involuntary park which is now recognized as one of the most well-preserved areas of temperate habitat in the world.[76] In 1966 it was first proposed that the DMZ be turned into a national park.[77]

Several endangered animal and plant species now exist among the heavily fortified fences, landmines and listening posts. These include the endangered red-crowned crane (a staple of Asian art), the white-naped crane, and, potentially, the extremely rare Siberian tiger,[76] Amur leopard, and Asiatic black bear. Ecologists have identified some 2,900 plant species, 70 types of mammals and 320 kinds of birds within the narrow buffer zone.[76] Additional surveys are now being conducted throughout the region.[78]

The DMZ owes its varied biodiversity to its geography, which crosses mountains, prairies, swamps, lakes, and tidal marshes. Environmentalists hope that the DMZ will be conserved as a wildlife refuge, with a well-developed set of objective and management plans vetted and in place. In 2005, CNN founder and media mogul Ted Turner, on a visit to North Korea, said that he would financially support any plans to turn the DMZ into a peace park and a UN-protected World Heritage Site.[79]

In September 2011, South Korea submitted a nomination form to Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB) in UNESCO for designation of 435 km2 (168 sq mi) in the southern part of the DMZ below the Military Demarcation Line, as well as 2,979 km2 (1,150 sq mi) in privately controlled areas, as a Biosphere Reserve according to the Statutory Framework of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves.[80] MAB National Committee of the Republic of Korea mentioned only southern part of DMZ to be nominated since there was no response from Pyongyang when it requested Pyongyang to push jointly. North Korea is a member nation of the international coordinating council of UNESCO's Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme, which designates Biosphere Reserves.[81]

North Korea opposed the application as a violation of the armistice agreement during the council's meeting in Paris on July 9 to 13. The South Korean government's attempt to designate the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve was turned down at UNESCO's MAB council meeting in Paris in July 2012. Pyongyang expressed its opposition by sending letters to 32 council member countries, except for South Korea, and the UNESCO headquarters a month prior to the meeting. At the council meeting, Pyongyang said the designation violated the Armistice Agreement.[82]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Korean Demilitarized Zone: Image of the Day". NASA Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on 16 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ↑ Walker, Philip (24 June 2011). "The world's most dangerous borders". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017.

- ↑ Elferink, Alex G. Oude. (1994). The Law of Maritime Boundary Delimitation: a Case Study of the Russian Federation, p. 314, at Google Books

- ↑ Ahn, JH (2016-03-21). "On patrol in the DMZ: North Korean landmines, biting winds and tin cans: As tensions on the peninsula escalate, a former South Korean guard describes life at one of the world's most fortified borders. NK News reports". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 2016-04-18.

- ↑ Potts, Rolf (3 February 1999). "Korea's no-man's-land". Salon. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 "DMZ sixth-graders become graduates". Stars and Stripes. 2008-02-19. Archived from the original on 11 June 2009.

- ↑ "Santa mobbed by students during visit to Joint Security Area". army.mil.com -The Official U.S. Army Website. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-11.

- ↑ Kwaak, Jeyup S (24 September 2014). "Why the Korean Peninsula Keeps Land Mines". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014.

- ↑ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/10/01/north-south-korea-begin-removing-landmines-along-fortified-border/

- ↑ "Panmunjon". army.mil.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ "General revisits deadly 1984 Thanksgiving firefight at DMZ". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ "Korea Demilitarized Zone Incidents". 2009-05-28. Archived from the original on 31 March 2010.

- ↑ "South Korea to revamp DMZ towers". Stars and Stripes. 2009-10-22. Archived from the original on 22 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- 1 2 Potts, Rolf (1999-02-03). "Korea's no-man's-land". Salon. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013.

- ↑ O'Neill, Tom. "Korea's DMZ: Dangerous Divide". National Geographic, July 2003.

- ↑ Silpasornprasit, Susan. "Day trip to the DMZ: A look inside the Korean Demilitarized Zone". Archived 30 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. IMCOM-Korea Region Public Affairs Office, US Army. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ "CNN.com – Korea's DMZ: 'Scariest place on Earth'". 2002-02-20. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ 개성에 '구멍탄' 5만장 배달했습니다. economy.ohmynews.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- ↑ "North Korea: Chronology of Provocations, 1950 – 2003" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2006. Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ↑ Bolger, Daniel (1991). Scenes from an Unfinished War: Low intensity conflict in Korea 1966–1969. Diane Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-7881-1208-9.

- ↑ "Scenes from an Unfinished War: Low-Intensity Conflict in Korea, 1966–1968" (PDF). Cgsc.leavenworth.army.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ↑ "Minutes of Washington Special Actions Group Meeting, Washington, 25 August 1976, 10:30 a.m." Office of the Historian, US Department of State. 25 August 1976. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

Clements: I like it. It doesn't have an overt character. I have been told that there have been 200 other such operations and that none of these have surfaced. Kissinger: It is different for us with the War Powers Act. I don't remember any such operations.

- ↑ Lee Tae-hoon (7 February 2011). "S. Korea raided North with captured agents in 1967". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ↑ Sides, Jim (2009). Almost Home. Xulon Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-60791-740-3.

- ↑ "Demilitarized Zone". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on 5 November 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ↑ Bermudez, Joseph S. Jr. "Tunnels under the DMZ". korean-war.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-21. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ↑ Robinson, Martin (2009). Seoul. Lonely Planet. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-74104-774-5.

- ↑ "The Fourth Infiltration Tunnel". Panmunjom Travel Center. Archived from the original on 9 March 2007.

- 1 2 "Welcome to North Korea: A film by Peter Tetteroo for KRO Television". Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ Salzinger, Caroline (2008). Terveisiä pahan akselilta: Arkea ja politiikkaa maailman suljetuimmissa valtioissa (in Finnish). Translated by Lempinen, Ulla. Jyväskylä: Atena. p. 40. ISBN 978-951-796-521-7.

- ↑ "DMZ: Demilitarized Zone". Korea Konsult. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ↑ "New York Times, 1999". Korean-war.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-02.

- ↑ "Tear Down the Korean Wall". DPRK UN Mission. 1999-12-03. Archived from the original on 29 March 2006. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ↑ Eckholm, Erik (December 8, 1999). "Where Most See Ramparts, North Korea Imagines a Wall". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ↑ Ángela Gallardo Bernal (9 November 2014). "10 Days in North Korea". RT. at 19:30. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ Herskovitz, Jon (December 31, 2007). "North Korea asks South to tear down imaginary wall". Reuters. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ↑ https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-45704909

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 2017-03-12. Bottom of the page. Retrieved 11 March 2017

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-12. Retrieved 11 March 2017

- ↑ Norimitsu Onishi (15 February 2014). "South Korean Movie Unlocks Door on a Once-Secret Past". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ↑ "The growing danger of great-power conflict". The Economist. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- 1 2 "Koreas switch off loudspeakers". BBC. 15 June 2004. Archived from the original on 15 June 2004. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Choe Sang-hun (10 August 2015). "South Korea Accuses the North After Land Mines Maim Two Soldiers in DMZ". New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ Park, Ju-Min (2015-08-10). "South Korea condemns North over land mine blast, vows retaliation". Seoul: Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-10.

- ↑ "North Korea and South Korea Trade Fire Across Border, Seoul Says". The New York Times. 21 August 2015. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ "South Korea turns off propaganda as Koreas reach deal". 2015-08-25. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-25.

- ↑ Kim, Sam (2016-01-07). "South Korea Punishes Kim Jong Un With K-Pop for Nuclear Test". Bloomsberg. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ↑ Simon Sharwood (15 April 2016). "South Korea to upgrade national stereo defence system for US$16m". The Register. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ↑ Jung 2014, p. 16.

- ↑ Jung 2014, p. 9.

- ↑ Higginbotham, Adam (5 June 2014). "The No-Tech Tactics of North Korea's Most Wanted Defector". Bloomberg News. p. 4. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Jung 2014, p. 23.

- ↑ Feffer, John (6 November 2014). "Korea's Balloon War". Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ Jung 2014, p. 31.

- ↑ Friedman, Herbert A. (5 January 2006). "Communist Korean War Leaflets". www.psywarrior.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ https://www.cnn.com/2018/04/23/asia/north-korea-south-korea-upcoming-summit-intl/index.html

- ↑ "North And South Korea Dismantle Loudspeakers Blaring Propaganda On The DMZ : The Two-Way". NPR. 2018-05-01. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- ↑ https://www.pri.org/stories/2018-05-05/south-korea-faces-decision-over-leaflets-ties-warm-north

- ↑ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/05/05/south-korea-sabotages-anti-north-korea-leaflet-drop/

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-11. Retrieved 10 March 2017

- ↑ http://www.koreana.or.kr/user/0003/nd6245.do?View&boardNo=00000415&pubLang=English&pubYear=2016&pubMonth=AUTUMN&zineInfoNo=0003 Retrieved 10 March 2017

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-11. / up-close map of CCL/CCZ/Southern Limit Line. Retrieved 10 March 2017

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 2014-04-14. Article 1, Section 5. Retrieved 11 March 2017

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-11. Retrieved 11 March 2017

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-11. Retrieved 11 March 2017

- ↑ Koehler, Rober. (2011). The DMZ: Dividing the Two Koreas, p. 108, at Google Books

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-11. Retrieved 10 March 2017. Many pictures, maps, and description of the old Taebong capital that is stuck in the middle of the DMZ.

- ↑ Chang, Jae-Soon (2008-11-28). "Last train to Kaesong as Korean relations cool". Edinburgh: News.Scotman.Com.

- ↑ "Inter-Korean economic cooperation Kaesong office reopens". Englishhani. 2009-09-07. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ↑ "ROK woman tourist shot dead at DPRK resort". China Daily. 2008-07-12. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012.

- ↑ "N Korea steps up row with South". BBC. 2008-08-03. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009.

- ↑ "North Korea 'to seize property at Kumgang resort'". BBC. 2010-04-23.

- ↑ "Korail". www.letskorail.com.

- ↑ Brady, Lisa (13 April 2012). "How wildlife is thriving in the Korean peninsula's demilitarised zone". Archived from the original on 5 September 2016 – via The Guardian.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Korea's DMZ: The thin green line". CNN. 2003-08-22. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ↑ Paige, Glenn D. (January 1967). "1966: Korea Creates the Future". Asian Survey - A Survey of Asia in 1966: Part I. 7 (1): 21–30. doi:10.2307/2642450. JSTOR 2642450.

- ↑ "Korean 'Tigerman' Prowls the DMZ". International Korean News. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ↑ "Ted Turner: Turn Korean DMZ into peace park". USA TODAY. 2005-11-18. Archived from the original on 6 December 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ Choi, Chungil. "Nomination of Korea DMZ Biosphere Reserve" (PDF). Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ Kim, Jeong-su. "Seoul to seek UNESCO Biosphere Reserve status for DMZ". Hankyoreh. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ↑ Cho, Do-soon (14 August 2012). "Biosphere reserve status for the DMZ is urgent". JoonAng Daily. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

References

- Bermudez, Joseph S. (2001). Shield of the Great Leader. The Armed Forces of North Korea. The Armed Forces of Asia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86448-582-0.

- Mullen, Jethro; Novak, Kathy (August 10, 2015). "South Korea warns North will pay 'harsh price' over DMZ landmine blasts". CNN World News. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- Elferink, Alex G. Oude, (1994). The Law of Maritime Boundary Delimitation: a Case Study of the Russian Federation. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 9780792330820; OCLC 123566768

- Jung, Jin-Heon (2014). "Ballooning Evangelism: Psychological Warfare and Christianity in the Divided Korea" (PDF). Max Planck Institute. MMG Working Paper. pp. 7–33. ISSN 2192-2357. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Korean Demilitarized Zone. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for DMZ (Korea). |

- U.S. Army official Korean Demilitarized Zone image archive

- Washington Post Correspondent Amar Bakshi travels to the Korean Demilitarized Zone... And uncovers the world's most dangerous tourist trap, January 2008.

- Status and ecological resource value of the Republic of Korea's De-militarized Zone

- Tour Of DMZ on YouTube. Dec. 2007

- Tour of DMZ from the DPRK on YouTube, 2016

- 360 degree tour of DMZ from the DPRK on YouTube, 2016

- DMZ Forum: Collaborative international NGO focusing on promoting peace and conservation within the Korean DMZ region

- ABCNews/Yahoo! report/blog on the DMZ

- The World’s Most Dangerous Border – A Tour of North Korea’s DMZ Visiting the DMZ from Pyongyang.

- Photo of road linking DPRK to Paju, ROK

.jpg)