Hanoi

| Hanoi Hà Nội | ||

|---|---|---|

| Municipality | ||

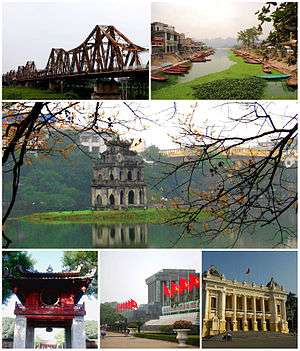

(from left) top: Temple of Literature, Turtle Tower; middle: Flag Tower of Hanoi, Hanoi Opera House, Long Biên Bridge; bottom: One Pillar Pagoda, Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum | ||

| ||

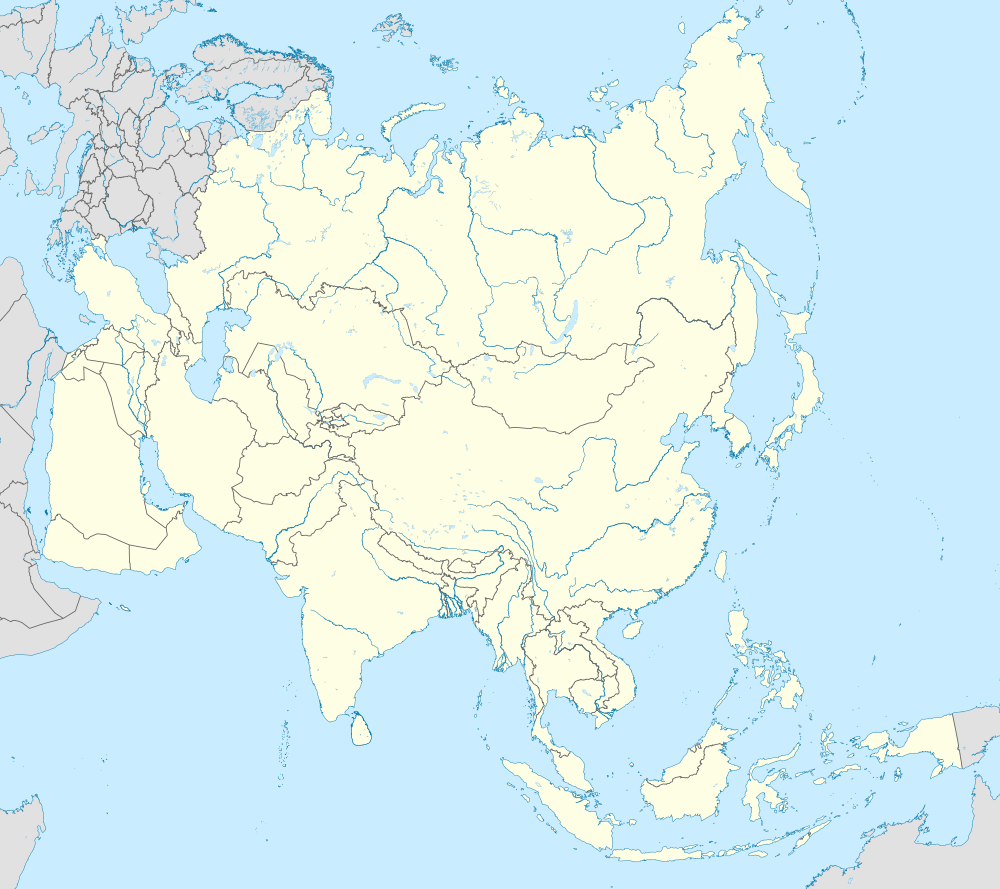

Provincial location in Vietnam | ||

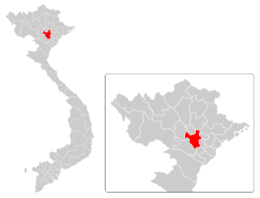

Hanoi Provincial location in Vietnam  Hanoi Hanoi (Southeast Asia)  Hanoi Hanoi (Asia) .svg.png) Hanoi Hanoi (Earth) | ||

| Coordinates: 21°01′42″N 105°51′15″E / 21.02833°N 105.85417°ECoordinates: 21°01′42″N 105°51′15″E / 21.02833°N 105.85417°E | ||

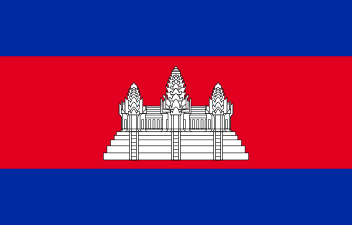

| Country | Vietnam | |

| Central city | Hà Nội | |

| Central district | Hoan Kiem and Ba Dinh | |

| Foundation as capital of the Đại Việt | 1010 | |

| Establishment as capital of Vietnam | 2 September 1945 | |

| Founded by | Lý Thái Tổ | |

| Demonym | Hanoians | |

| Government | ||

| • Party's Secretary | Hoàng Trung Hải | |

| • Chairman of People's Council | Nguyễn Thị Bích Ngọc | |

| • Chairman of People's Committee | Nguyễn Đức Chung | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Municipality | 3,328.9 km2 (1,292 sq mi) | |

| • Urban | 319.56 km2 (123.38 sq mi) | |

| • Metro | 24,314.7 km2 (9,388.0 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015)[1] | ||

| • Municipality | 7,587,800 | |

| • Rank | 2nd in Vietnam | |

| • Density | 2,300/km2 (5,900/sq mi) | |

| • Urban | 3,435,394 | |

| • Urban density | 14,708.8/km2 (38,096/sq mi) | |

| • Metro | 16,100,000 | |

| • Metro density | 662.1/km2 (1,715/sq mi) | |

| GDP (nominal) (2017 estimate) | ||

| • Total | 31.2 billion USD | |

| • Per capita | 4,031 USD[2] | |

| • Growth |

| |

| Time zone | UTC+07:00 (ICT) | |

| Area codes | 24 | |

| Climate | Cwa | |

| Website |

www | |

| Hanoi | |

.svg.png) "Hanoi" in chữ Hán (Chinese characters) | |

| Vietnamese name | |

|---|---|

| Vietnamese alphabet | Hà Nội |

| Chữ Hán | 河內 |

Hanoi (UK: /hæˈnɔɪ/,[3] US: /hɑː-/;[4] Vietnamese: Hà Nội [hàː nôjˀ] (![]()

From 1010 until 1802, it was the most important political centre of Vietnam. It was eclipsed by Huế, the imperial capital of Vietnam during the Nguyễn Dynasty (1802–1945). In 1873 Hanoi was conquered by the French. From 1883 to 1945, the city was the administrative center of the colony of French Indochina. The French built a modern administrative city south of Old Hanoi, creating broad, perpendicular tree-lined avenues of opera, churches, public buildings, and luxury villas, but they also destroyed large parts of the city, shedding or reducing the size of lakes and canals, while also clearing out various imperial palaces and citadels.

From 1940 to 1945 Hanoi, as well as the largest part of French Indochina and Southeast Asia, was occupied by the Japanese. On September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam). The Vietnamese National Assembly under Ho Chi Minh decided on January 6, 1946, to make Hanoi the capital of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. From 1954 to 1976, it was the capital of North Vietnam, and it became the capital of a reunified Vietnam in 1976, after the North's victory in the Vietnam War.

October 2010 officially marked 1,000 years since the establishment of the city.[6] The Hanoi Ceramic Mosaic Mural is a 6.5 km (4.0 mi) ceramic mosaic mural created to mark the occasion.

Names

Hanoi had many official and unofficial names throughout history.

- During the Chinese occupation of Vietnam, it was known first as Long Biên (龍邊, "dragon edge"), then Tống Bình (宋平, "Song peace") and Long Đỗ (龍肚, "dragon belly"). Long Biên later gave its name to the famed Long Biên Bridge, built during French colonial times, and more recently to a new district to the east of the Red River. Several older names of Hanoi feature long (龍, "dragon"), linked to the curvy formation of the Red River around the city, which was symbolized as a dragon.[7]

- In 866, it was turned into a citadel and named Đại La (大羅, "big net"). This gave it the nickname La Thành (羅城, "net citadel"). Both Đại La and La Thành are names of major streets in modern Hanoi.

- When Lý Thái Tổ established the capital in the area in 1010, it was named Thăng Long (昇龍, "rising dragon"). Thăng Long later became the name of a major bridge on the highway linking the city center to Noi Bai Airport, and the Thăng Long Boulevard expressway in the southwest of the city center. In modern time, the city is usually referred to as Thăng Long – Hà Nội, when its long history is discussed.

- During the Hồ dynasty, it was called Đông Đô (東都, "eastern metropolis").

- During the Ming Chinese occupation, it was called Đông Quan (東關, "eastern gate").

- During the Lê dynasty, Hanoi was known as Đông Kinh (東京, "eastern capital"). This gave the name to Tonkin and Gulf of Tonkin. A square adjacent to the Hoàn Kiếm lake was named Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục after the reformist Tonkin Free School under French colonization.

- After the end of the Tây Sơn had expanded further south, the city was named Bắc Thành (北城, "northern citadel").

- Minh Mạng renamed the city Hà Nội (河內, "inside (the) river") in 1831. This has remained its official name until modern times.

- Several unofficial names of Hanoi include: Kẻ Chợ (marketplace), Tràng An (long peace), Hà Thành (short for Thành phố Hà Nội, "city of Hanoi"), and Thủ Đô (capital).

History

Pre-Thăng Long period

Hanoi has been inhabited since at least 3000 BC. The Cổ Loa Citadel in Dong Anh district[8] served as the capital of the Âu Lạc kingdom founded by the Thục emigrant Thục Phán after his 258 BC conquest of the native Văn Lang.

In 197 BC, Âu Lạc Kingdom was annexed by Nanyue, which ushered in more than a millennium of Chinese domination. By the middle of the 5th century, in the center of ancient Hanoi, the Liu Song Dynasty set up a new district (縣) called Songping (Tong Binh), which later became a commandery (郡), including two districts Yihuai (義懷) and Suining (綏寧) in the south of the Red River (now Từ Liêm and Hoài Đức districts) with a metropolis (the domination centre) in the present inner Hanoi. By the year 679, the Tang dynasty changed the region's name into Annan (Pacified South), with Songping as its capital.[9]

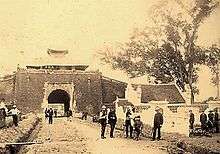

In order to defeat the people's uprisings, in the later half of the 8th century, Zhang Boyi (張伯儀), a Tang dynasty viceroy, built Luocheng (羅城, La Thanh or La citadel, from Thu Le to Quan Ngua in present-day Ba Dinh precinct). In the earlier half of the 9th century, it was further built up and called Jincheng (金城, Kim Thanh or Kim Citadel). In 866, Gao Pian, the Chinese Jiedushi, consolidated and named it Daluocheng (大羅城, Dai La citadel, running from Quan Ngua to Bach Thao), the largest citadel of ancient Hanoi at the time.[9]

Thăng Long, Đông Đô, Đông Quan, Đông Kinh

In 1010, Lý Thái Tổ, the first ruler of the Lý Dynasty, moved the capital of Đại Việt to the site of the Đại La Citadel. Claiming to have seen a dragon ascending the Red River, he renamed the site Thăng Long (昇龍, "Soaring Dragon") – a name still used poetically to this day. Thăng Long remained the capital of Đại Việt until 1397, when it was moved to Thanh Hóa, then known as Tây Đô (西都), the "Western Capital". Thăng Long then became Đông Đô (東都), the "Eastern Capital."

In 1408, the Chinese Ming Dynasty attacked and occupied Vietnam, changing Đông Đô's name to Dongguan (Chinese: 東關, Eastern Gateway), or Đông Quan in Sino-Vietnamese. In 1428, the Vietnamese overthrew the Chinese under the leadership of Lê Lợi,[10] who later founded the Lê Dynasty and renamed Đông Quan Đông Kinh (東京, "Eastern Capital") or Tonkin. Right after the end of the Tây Sơn Dynasty, it was named Bắc Thành (北城, "Northern Citadel").

During Nguyễn Dynasty and the French colonial period

In 1802, when the Nguyễn Dynasty was established and moved the capital to Huế, the old name Thăng Long was modified to become Thăng Long (昇隆, "Soaring Dragon"). In 1831, the Nguyễn emperor Minh Mạng renamed it Hà Nội (河内, "Between Rivers" or "River Interior"). Hanoi was occupied by the French in 1873 and passed to them ten years later. As Hanoï, it was located in the protectorate of Tonkin became the capital of French Indochina after 1887.[10]

During two wars

The city was occupied by the Imperial Japanese in 1940 and liberated in 1945, when it briefly became the seat of the Viet Minh government after Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the independence of Vietnam. However, the French returned and reoccupied the city in 1946. After nine years of fighting between the French and Viet Minh forces, Hanoi became the capital of an independent North Vietnam in 1954.

During the Vietnam War, Hanoi's transportation facilities were disrupted by the bombing of bridges and railways. These were all, however, promptly repaired. Following the end of the war, Hanoi became the capital of a reunified Vietnam when North and South Vietnam were reunited on 2 July 1976.

Modern Hanoi

After the Đổi Mới economic policies were approved in 1986, the Communist Party and national and municipal governments hoped to attract international investments for urban development projects in Hanoi.[11] The high-rise commercial buildings did not begin to appear until ten years later due to the international investment community being skeptical of the security of their investments in Vietnam.[11] Rapid urban development and rising costs displaced many residential areas in central Hanoi.[11] Following a short period of economic stagnation after the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Hanoi resumed its rapid economic growth.[11]

On 29 May 2008, it was decided that Hà Tây Province, Vĩnh Phúc Province's Mê Linh District and 4 communes of Lương Sơn District, Hòa Bình Province be merged into the metropolitan area of Hanoi from 1 August 2008.[12] Hanoi's total area then increased to 334,470 hectares in 29 subdivisions[13] with the new population being 6,232,940.,[13] effectively tripling its size. The Hanoi Capital Region (Vùng Thủ đô Hà Nội), a metropolitan area covering Hanoi and 6 surrounding provinces under its administration, will have an area of 13,436 square kilometres (5,188 sq mi) with 15 million people by 2020.

Hanoi has experienced a rapid construction boom recently. Skyscrapers, popping up in new urban areas, have dramatically changed the cityscape and have formed a modern skyline outside the old city. In 2015, Hanoi is ranked # 39 by Emporis in the list of world cities with most skyscrapers over 100 m; its two tallest buildings are Hanoi Landmark 72 Tower (336 m, tallest in Vietnam and second tallest in southeast Asia after Malaysia's Petronas Twin Towers) and Hanoi Lotte Center (272 m, also, second tallest in Vietnam).

Public outcry in opposition to the redevelopment of culturally significant areas in Hanoi persuaded the national government to implement a low-rise policy surrounding Hoàn Kiếm Lake.[11] The Ba Đình District is also protected from commercial redevelopment.[11]

Geography

Location, topography

Hanoi is located in northern region of Vietnam, situated in the Vietnam's Red River delta, nearly 90 km (56 mi) away from the coastal area. Hanoi contains three basic kinds of terrain, which are the delta area, the midland area and mountainous zone. In general, the terrain is gradually lower from the north to the south and from the west to the east, with the average height ranging from 5 to 20 meters above the sea level. The hills and mountainous zones are located in the northern and western part of the city. The highest peak is at Ba Vi with 1281 m, located west of the city proper.

Climate

Hanoi features a warm humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa) with plentiful precipitation.[14] The city experiences the typical climate of northern Vietnam, with 4 distinct seasons.[15] Summer, from May until August, is characterized by hot and humid weather with abundant rainfall.[15] September to October is fall, characterized by a decrease in temperature and precipitation.[15] Winter, from November to January, is dry and cool by national standards.[15] The city is usually cloudy and foggy in winter, averaging only 1.5 hours of sunshine per day in February and March.

Hanoi averages 1,680 millimetres (66.1 in) of rainfall per year, the majority falling from May to September. There are an average of 114 days with rain.[15]

The average annual temperature is 23.6 °C (74 °F) with a mean relative humidity of 79%.[15] The highest recorded temperature was 42.8 °C (109 °F) on May 1926 while the lowest recorded temperature was 2.7 °C (37 °F) on January 1955.[15]

| Climate data for Hanoi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.0 (89.6) |

34.7 (94.5) |

37.2 (99) |

39.0 (102.2) |

42.8 (109) |

42.5 (108.5) |

40.1 (104.2) |

38.2 (100.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

36.6 (97.9) |

34.7 (94.5) |

31.5 (88.7) |

42.8 (109) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 19.7 (67.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

27.2 (81) |

31.4 (88.5) |

32.9 (91.2) |

33.1 (91.6) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.2 (88.2) |

28.8 (83.8) |

25.3 (77.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

27.2 (81) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 16.4 (61.5) |

17.2 (63) |

20.0 (68) |

23.9 (75) |

27.4 (81.3) |

28.9 (84) |

29.2 (84.6) |

28.6 (83.5) |

27.5 (81.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

18.2 (64.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.6 (76.3) |

26.1 (79) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.9 (76.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

18.9 (66) |

15.6 (60.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

17.2 (63) |

20.0 (68) |

21.0 (69.8) |

22.2 (72) |

16.1 (61) |

14.0 (57.2) |

10.0 (50) |

5.0 (41) |

2.7 (36.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 18 (0.71) |

19 (0.75) |

34 (1.34) |

105 (4.13) |

165 (6.5) |

266 (10.47) |

253 (9.96) |

274 (10.79) |

243 (9.57) |

156 (6.14) |

59 (2.32) |

20 (0.79) |

1,611 (63.43) |

| Average rainy days | 10.3 | 12.4 | 16.0 | 14.4 | 14.5 | 14.6 | 15.6 | 16.9 | 13.6 | 10.9 | 7.9 | 5.0 | 152.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 80.9 | 83.4 | 87.9 | 89.4 | 86.5 | 82.9 | 82.2 | 85.9 | 87.2 | 84.2 | 81.9 | 81.3 | 82.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 74 | 47 | 47 | 90 | 183 | 172 | 195 | 174 | 176 | 167 | 137 | 124 | 1,585 |

| Source #1: Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology[16] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Pogoda.ru.net (records),[17] (May record high and January record low only),[15] Vietnamnet.vn (June record high only),[18] Tutiempo.net (March and April record low only),[19][20] Nchmf.gov.vn[21] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Hà Đông district | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.3 (88.3) |

34.9 (94.8) |

38.9 (102) |

39.9 (103.8) |

37.9 (100.2) |

39.5 (103.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

37.7 (99.9) |

36.2 (97.2) |

34.6 (94.3) |

34.6 (94.3) |

30.7 (87.3) |

39.9 (103.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

27.2 (81) |

31.1 (88) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

32.2 (90) |

30.9 (87.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

22.2 (72) |

27.2 (81) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

17.4 (63.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

28.8 (83.8) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.4 (83.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

23.5 (74.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.8 (78.4) |

24.4 (75.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

6.1 (43) |

7.3 (45.1) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.8 (69.4) |

22.5 (72.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 24 (0.94) |

27 (1.06) |

39 (1.54) |

91 (3.58) |

179 (7.05) |

239 (9.41) |

229 (9.02) |

272 (10.71) |

235 (9.25) |

196 (7.72) |

97 (3.82) |

43 (1.69) |

1,670 (65.75) |

| Average precipitation days | 9.8 | 12.2 | 15.1 | 14.1 | 14.4 | 14.2 | 14.9 | 15.7 | 13.6 | 11.3 | 8.4 | 6.2 | 149.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84.6 | 86.0 | 87.9 | 89.4 | 86.5 | 82.9 | 82.2 | 85.9 | 87.2 | 84.2 | 81.9 | 81.3 | 85.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 71 | 48 | 57 | 93 | 178 | 171 | 195 | 178 | 178 | 159 | 141 | 124 | 1,593 |

| Source: Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology[16] | |||||||||||||

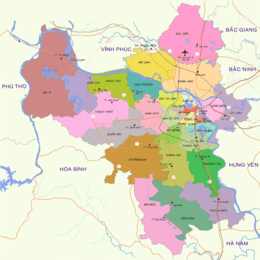

Administrative divisions

Hà Nội is divided into 12 urban districts, 1 district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. When Hà Tây was merged into Hanoi in 2008, Hà Đông was transformed into an urban district while Sơn Tây degraded to a district-leveled town. They are further subdivided into 22 commune-level towns (or townlets), 399 communes, and 145 wards.

List of local government divisions

| Subdivisions of Hanoi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provincial Cities/Districts[22] | Wards[22] | Area (km2)[22] | Population[22] | |

| 1 town (Thị xã) | ||||

| Sơn Tây TownHT | 15 | 117,43 | 150,300 | |

| 12 urban districts (Quận) | ||||

| Ba Đình District | 14 | 9.224 | 247,100 | |

| Bắc Từ Liêm District | 13 | 43.35 | 333,300 | |

| Cầu Giấy District | 8 | 12.04 | 266,800 | |

| Đống Đa District | 21 | 9.96 | 420,900 | |

| Hai Bà Trưng District | 20 | 10.09 | 318,000 | |

| Hà Đông DistrictHT | 17 | 47.917 | 319,800 | |

| Hoàn Kiếm District | 18 | 5.29 | 160,600 | |

| Hoàng Mai District | 14 | 41.04 | 411,500 | |

| Long Biên District | 14 | 60.38 | 291,900 | |

| Nam Từ Liêm District | 10 | 32.27 | 236,700 | |

| Tây Hồ District | 8 | 24 | 168,300 | |

| Thanh Xuân District | 11 | 9.11 | 285,400 | |

| Subtotal | 145 | 233.56 | 3,435,394 | |

| 17 rural districts (Huyện) | ||||

| Ba Vì DistrictHT | 31 + 1 town | 428.0 | 282,600 | |

| Chương Mỹ DistrictHT | 30 + 2 towns | 237,4 | 331,100 | |

| Đan Phượng DistrictHT | 15 + 1 town | 78.8 | 162,900 | |

| Đông Anh District | 23 + 1 town | 185.6 | 381,500 | |

| Gia Lâm District | 20 + 2 towns | 116.0 | 276,300 | |

| Hoài Đức DistrictHT | 19 + 1 town | 95.3 | 229,400 | |

| Mê Linh District | 16 + 2 towns | 142.26 | 226,800 | |

| Mỹ Đức DistrictHT | 21 + 1 town | 230.0 | 204,800 | |

| Phú Xuyên DistrictHT | 26 + 2 towns | 171.1 | 211,100 | |

| Phúc Thọ DistrictHT | 25 + 1 town | 113.2 | 182,300 | |

| Quốc Oai DistrictHT | 20 + 1 town | 136.0 (2001) | 188,000 | |

| Sóc Sơn District | 25 + 1 town | 306.51 | 340,700 | |

| Thanh Trì District | 15 + 1 town | 63.4 | 256,800 | |

| Thanh Oai DistrictHT | 20 + 1 town | 129.6 | 205,200 | |

| Thạch Thất DistrictHT | 22 + 1 town | 128.1 | 207,500 | |

| Thường Tín DistrictHT | 28 + 1 town | 130.7 | 247,700 | |

| Ứng Hòa DistrictHT | 28 + 1 town | 188.72 | 204,800 | |

| Subtotal | 399 + 22 towns | 3,266.186 | 3,972,851 | |

| Total | 559 + 22 towns | 3,344.47 | 7,408,245 | |

HT – formerly an administrative subdivision unit of the defunct Hà Tây Province

Demographics

Hanoi's population is constantly growing (about 3.5% per year), a reflection of the fact that the city is both a major metropolitan area of Northern Vietnam, and also the country's political centre. This population growth also puts a lot of pressure on the infrastructure, some of which is antiquated and dates back to the early 20th century.

The number of Hanoians who have settled down for more than three generations is likely to be very small when compared to the overall population of the city. Even in the Old Quarter, where commerce started hundreds of years ago and consisted mostly of family businesses, many of the street-front stores nowadays are owned by merchants and retailers from other provinces. The original owner family may have either rented out the store and moved into the adjoining house or moved out of the neighbourhood altogether. The pace of change has especially escalated after the abandonment of central-planning economic policies and relaxing of the district-based household registrar system.

Hanoi's telephone numbers have been increased to 8 digits to cope with demand (October 2008). Subscribers' telephone numbers have been changed in a haphazard way; however, mobile phones and SIM cards are readily available in Vietnam, with pre-paid mobile phone credit available in all areas of Hanoi.

Economy

Hanoi has the highest Human Development Index among the cities in Vietnam. According to a recent ranking by PricewaterhouseCoopers, Hanoi will be the fastest growing city in the world in terms of GDP growth from 2008 to 2025.[23] In the year 2013, Hanoi contributed 12.6% to GDP, exported 7.5% of total exports, contributed 17% to the national budget and attracted 22% investment capital of Vietnam. The city's nominal GDP at current prices reached 451,213 billion VND (21.48 billion USD) in 2013, which made per capita GDP stand at 63.3 million VND (3,000 USD).[24] Industrial production in the city has experienced a rapid boom since the 1990s, with average annual growth of 19.1 percent from 1991–95, 15.9 percent from 1996–2000, and 20.9 percent during 2001–2003. In addition to eight existing industrial parks, Hanoi is building five new large-scale industrial parks and 16 small- and medium-sized industrial clusters. The non-state economic sector is expanding fast, with more than 48,000 businesses currently operating under the Enterprise Law (as of 3/2007).[25]

Trade is another strong sector of the city. In 2003, Hanoi had 2,000 businesses engaged in foreign trade, having established ties with 161 countries and territories. The city's export value grew by an average 11.6 percent each year from 1996–2000 and 9.1 percent during 2001–2003. The economic structure also underwent important shifts, with tourism, finance, and banking now playing an increasingly important role. Hanoi's traditional business districts are Hoàn Kiếm, Hai Bà Trưng and Đống Đa; and newly developing Cầu Giấy and Nam Từ Liêm in the west.

Similar to Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi enjoys a rapidly developing real estate market.[26] The current most notable new urban areas are central Trung Hòa Nhân Chính, Mỹ Đình, the luxurious zones of The Manor, Ciputra, Royal City in the Nguyễn Trãi Street (Thanh Xuân District) and Times City in the Hai Bà Trưng District.

Agriculture, previously a pillar in Hanoi's economy, has striven to reform itself, introducing new high-yield plant varieties and livestock, and applying modern farming techniques.[27]

After the economic reforms that initiated economic growth, Hanoi's appearance has also changed significantly, especially in recent years. Infrastructure is constantly being upgraded, with new roads and an improved public transportation system.[28] Hanoi has allowed many fast-food chains into the city, such as Jollibee, Lotteria, Pizza Hut, KFC, and others. Locals in Hanoi perceive the ability to purchase "fast-food" as an indication of luxury and permanent fixtures.[29]

Over three-quarters of the jobs in Hanoi are state-owned. 9% of jobs are provided by collectively owned organizations. 13.3% of jobs are in the private sector.[30] The structure of employment has been changing rapidly as state-owned institutions downsize and private enterprises grow.[30] Hanoi has in-migration controls which allow the city to accept only people who add skills Hanoi's economy.[30] A 2006 census found that 5,600 rural produce vendors exist in Hanoi, with 90% of them coming from surrounding rural areas. These numbers indicate the much greater earning potential in urban rather than in rural spaces.[29] The uneducated, rural, and mostly female street vendors are depicted as participants of "microbusiness" and local grassroots economic development by business reports.[29] In July 2008, Hanoi's city government devised a policy to partially ban street vendors and side-walk based commerce on 62 streets due to concerns about public health and "modernizing" the city's image to attract foreigners.[29] Many foreigners believe that the vendors add a traditional and nostalgic aura to the city, although street vending was much less common prior to the 1986 Đổi Mới policies.[29] The vendors have not able to form effective resistance tactics to the ban and remain embedded in the dominant capitalist framework of modern Hanoi.[31]

Development

Infrastructural development

A development master plan for Hanoi was designed by Ernest Hebrard in 1924, but was only partially implemented.[30] The close relationship between the Soviet Union and Vietnam led to the creation of the first comprehensive plan for Hanoi with the assistance of Soviet planners between 1981 and 1984.[32] It was never realized because it appeared to be incompatible with Hanoi's existing layout.[30]

In recent years, two master plans have been created to guide Hanoi's development.[30] The first was the Hanoi Master Plan 1990-2010, approved in April 1992. It was created out of collaboration between planners from Hanoi and the National Institute of Urban and Rural Planning in the Ministry of Construction.[30] The plan's three main objectives were to create housing and a new commercial center in an area known as Nghĩa Đô, expand residential and industrial areas in the Gia Lâm District, and develop the three southern corridors linking Hanoi to Hà Đông and the Thanh Trì District.[30] The end result of the land-use pattern was meant to resemble a five cornered star by 2010.[30] In 1998, a revised version of the Hanoi Master plan was approved to be completed in 2020.[30] It addressed the significant increase of population projections within Hanoi. Population densities and high rise buildings in the inner city were planned to be limited to protect the old parts of inner Hanoi.[30] A rail transport system is planned to be built to expand public transport and link the Hanoi to surrounding areas. Projects such as airport upgrading, a golf course, and cultural villages have been approved for development by the government.[30]

Hanoi is still faced with the problems associated with increasing urbanization. The disparity of wealth between the rich and the poor is a problem in both the capital and throughout the country.[30] Hanoi's public infrastructure is in poor condition. The city has frequent power cuts, air and water pollution, poor road conditions, traffic congestion, and a rudimentary public transit system. Traffic congestion and air pollution are worsening as the number of motor cycles increases. Squatter settlements are expanding on the outer rim of the city as homelessness rises.[30]

In the late 1980s, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Vietnamese government designed a project to develop rural infrastructure.[30] The project focused on improving roads, water supply and sanitation, and educational, health and social facilities because economic development in the communes and rural areas surrounding Hanoi is dependent on the infrastructural links between the rural and urban areas, especially for the sale of rural products.[30] The project aimed to use locally available resources and knowledge such as compressed earth construction techniques for building. It was jointly funded by the UNDP, the Vietnamese government, and resources raised by the local communities and governments. In four communes, the local communities contributed 37% of the total budget.[30] Local labor, community support, and joint funding were decided as necessary for the long-term sustainability of the project.[30]

Civil society development

Part of the goals of the dổi mới economic reforms was to decentralize governance for purpose of economic improvement. This led to the establishment of the first issue-oriented civic organizations in Hanoi. In the 1990s, Hanoi experienced significant poverty alleviation as a result of both the market reforms and civil society movements.[33] Most of the civic organizations in Hanoi were established after 1995, at a rate much slower than in Ho Chi Minh City.[34] Organizations in Hanoi are more "tradition-bound," focused on policy, education, research, professional interests, and appealing to governmental organizations to solve social problems.[35] This marked difference from Ho Chi Minh's civic organizations, which practice more direct intervention to tackle social issues, may be attributed to the different societal identities of North and South Vietnam.[36] Hanoi-based civic organizations use more systematic development and less of a direct intervention approach to deal with issues of rural development, poverty alleviation, and environmental protection. They rely more heavily on full-time staff than volunteers. In Hanoi, 16.7% of civic organizations accept anyone as a registered member and 73.9% claim to have their own budgets, as opposed to 90.9% in Ho Chi Minh City.[37] A majority of the civic organizations in Hanoi find it difficult to work with governmental organizations. Many of the strained relations between non-governmental and governmental organizations results from statism, a bias against non-state organizations on the part of government entities.[38]

Landmarks

As the capital of Vietnam for almost a thousand years, Hanoi is considered one of the main cultural centres of Vietnam, where most Vietnamese dynasties have left their imprint. Even though some relics have not survived through wars and time, the city still has many interesting cultural and historic monuments for visitors and residents alike. Even when the nation's capital moved to Huế under the Nguyễn Dynasty in 1802, the city of Hanoi continued to flourish, especially after the French took control in 1888 and modeled the city's architecture to their tastes, lending an important aesthetic to the city's rich stylistic heritage. The city hosts more cultural sites than any other city in Vietnam,[39] and boasts more than 1,000 years of history; that of the past few hundred years has been well preserved.[40]

Old Quarter

The Old Quarter, near Hoàn Kiếm Lake, maintains most of the original street layout and some of the architecture of old Hanoi. At the beginning of the 20th century Hanoi consisted of the "36 streets", the citadel, and some of the newer French buildings south of Hoàn Kiếm lake, most of which are now part of Hoàn Kiếm district.[41] Each street had merchants and households specializing in a particular trade, such as silk, jewelry or even bamboo. The street names still reflect these specializations, although few of them remain exclusively in their original commerce.[42] The area is famous for its specializations in trades such as traditional medicine and local handicrafts, including silk shops, bamboo carpenters, and tin smiths. Local cuisine specialties as well as several clubs and bars can be found here also. A night market (near Đồng Xuân Market) in the heart of the district opens for business every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday evening with a variety of clothing, souvenirs and food.

Some other prominent places include the Temple of Literature (Văn Miếu), site of the oldest university in Vietnam which was started in 1010, the One Pillar Pagoda (Chùa Một Cột) which was built based on the dream of king Lý Thái Tông (1028-1054) in 1049, and the Flag Tower of Hanoi (Cột cờ Hà Nội). In 2004, a massive part of the 900-year-old Hanoi Citadel was discovered in central Hanoi, near the site of Ba Đình Square.[43]

Lakes

A city between rivers built on lowlands, Hanoi has many scenic lakes and is sometimes called the "city of lakes." Among its lakes, the most famous are Hoàn Kiếm Lake, West Lake/Hồ Tây, and Bảy Mẫu Lake (inside Thống Nhất Park). Hoàn Kiếm Lake, also known as Sword Lake, is the historical and cultural center of Hanoi, and is linked to the legend of the magic sword. West Lake (Hồ Tây) is a popular place for people to spend time. It is the largest lake in Hanoi,with many temples in the area. The lakeside road in the Nghi Tam – Quang Ba area is perfect for bicycling, jogging and viewing the cityscape or enjoying the lotus ponds in the summer. The best way to see the majestic beauty of a West Lake sunset is to view it from one of the many bars around the lake, especially from The Summit at Pan Pacific Hanoi (formally known as Summit Lounge at Sofitel Plaza Hanoi).

Colonial Hanoi

.jpg)

Under French rule, as an administrative centre for the French colony of Indochina, the French colonial architecture style became dominant, and many examples remain today: the tree-lined boulevards (e.g. Phan Dinh Phung street) and its many villas, mansions, and government buildings. Many of the colonial structures are an eclectic mixture of French and traditional Vietnamese architectural styles, such as the National Museum of Vietnamese History, the Vietnam National Museum of Fine Arts and the old Indochina Medical College. Gouveneur-Général Paul Doumer (1898-1902) played a crucial role in colonial Hanoi's urban planning. Under his tenure there was a major construction boom.[44]

Notable French Colonial landmarks in Hanoi include:

- Presidential Palace

- Grand Opera House

- St. Joseph's Cathedral

- Long Biên Bridge

- Palais d'Expositions

- French School of the Far East

- Hotel Metropole

- Tonkin Palace (State Guest House)

- Hỏa Lò Prison

- Cửa Bắc Church

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs building

- Supreme Court building

- Indochina Medical College

- Museum of Revolution

- Central Station

Critical historians of empire have noted that French colonial rule imposed a system of white supremacy on the city. Vietnamese subjects supplied labor and tax revenue, but the privileges and comforts of the city went to the white population. French efforts at rat eradication revealed some of the colonial city's racial double-standards.[45]

Museums

Hanoi is home to a number of museums:

Tourism

Hanoi is sometimes dubbed the "Paris of the East" for its French influences.[46] With its tree-fringed boulevards, more than two dozen lakes and thousands of French colonial-era buildings, Hanoi is a popular tourist destination.

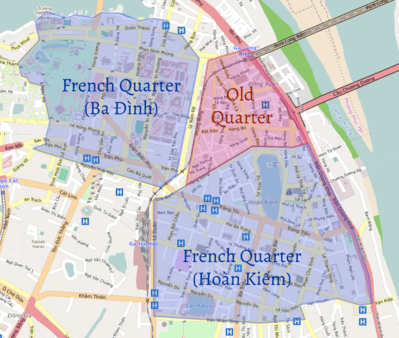

The tourist destinations in Hanoi are generally grouped into two main areas: the Old Quarter and the French Quarter(s). The "Old Quarter" is in the northern half of Hoàn Kiếm District with small street blocks and alleys, and a traditional Vietnamese atmosphere. Many streets in the Old Quarter have names signifying the goods ("hàng") the local merchants were or are specialized in. For example, "Hàng Bạc" (silver stores) still have many stores specializing in trading silver and jewelries.

Two areas are generally called the "French Quarters": the governmental area in Ba Đình District and the south of Hoàn Kiếm District. Both areas have distinctive French Colonial style villas and broad tree-lined avenues. The political center of Vietnam, Ba Đình has a high concentration of Vietnamese government headquarters, including the Presidential Palace, the National Assembly and several ministries and embassies, most of which used administrative buildings of colonial French Indochina. The One Pillar Pagoda, the Lycée du Protectorat and the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum are also in Ba Dinh. South of Hoàn Kiếm's "French Quarter" has several French-Colonial landmarks, including the Hanoi Opera House, the Sofitel Legend Metropole Hanoi hotel, the National Museum of Vietnamese History (formerly the École française d'Extrême-Orient), and the St. Joseph's Cathedral. Most of the French-Colonial buildings in Hoan Kiem are now used as foreign embassies.

Since 2014, Hanoi has consistently been voted in the world's top ten destinations by TripAdvisor. It ranked 8th in 2014,[47] 4th in 2015[48] and 8th in 2016.[49] Hanoi is the most affordable international destination in TripAdvisor's annual TripIndex report. In 2017, Hanoi will welcome more than 5 million international tourists.

Entertainment

A variety of options for entertainment in Hanoi can be found throughout the city. Modern and traditional theaters, cinemas, karaoke bars, dance clubs, bowling alleys, and an abundance of opportunities for shopping provide leisure activity for both locals and tourists. Hanoi has been named one of the top 10 cities for shopping in Asia by Water Puppet Tours.[50] The number of art galleries exhibiting Vietnamese art has dramatically increased in recent years, now including galleries such as "Nhat Huy" of Huynh Thong Nhat.

Nhà Triển Lãm at 29 Hang Bai street hosts regular photo, sculpture, and paint exhibitions in conjuncture with local artists and travelling international expositions.

A popular traditional form of entertainment is Water puppetry, which is shown, for example, at the Thăng Long Water Puppet Theatre.

Shopping

To adapt to Hanoi's rapid economic growth and high population density, many modern shopping centers and megamalls have been opened in Hanoi.

Major malls are:

- Trang Tien Plaza, High-end Mall on Trang Tien street (right next to Hoàn Kiếm Lake), Hoàn Kiếm District

- Vincom Center, a modern mall with hi-end CGV cineplex, Ba Trieu Street (just 2 km from Hoan Kiem lake), Hai Bà Trưng District

- Parkson Department Store, Tây Sơn Street, Đống Đa District;

- The Garden Shopping Center, Me Tri – Mỹ Đình, Nam Từ Liêm District

- Indochina Plaza, Xuan Thuy street, Cầu Giấy District

- Vincom Royal City Megamall, the largest underground mall in Asia with 230,000 square metres of shops, restaurants, cineplex, waterpark, ice skating rink; Nguyen Trai street (approx 6 km from Hoan Kiem Lake), Thanh Xuân District

- Vincom Times City Megamall, another megamall of 230,000 square metres including shops, restaurants, cineplex, huge musical fountain on central square and a giant aquarium; Minh Khai street (approx 5 km from Hoan Kiem Lake), Hai Ba Trung district

- Lotte Department Store, opened September 2014, Liễu Giai Street, Ba Đình District

- Aeon Mall Long Bien opened last October 2015, Long Bien District

Cuisine

Hanoi has rich culinary traditions. Many of Vietnam's most famous dishes, such as phở, chả cá, bánh cuốn and cốm are believed to have originated in Hanoi. Perhaps most widely known is Phở—a simple rice noodle soup often eaten as breakfast at home or at street-side cafes, but also served in restaurants as a meal. Two varieties dominate the Hanoi scene: Phở Bò, containing beef and Phở Gà, containing chicken. Bún chả, a dish consisting of charcoal roasted pork served in a sweet/salty soup with rice noodle vermicelli and lettuce, is by far the most popular food item among locals. President Obama famously tried this dish at a Le Van Huu eatery with Anthony Bourdain in 2016, prompting the opening of a Bún chả restaurant bearing his name in the Old Quarter.

Vietnam's national dish phở has been named as one of the Top 5 street foods in the world by globalpost.[51]

Hanoi has a number of restaurants whose menus specifically offer dishes containing snake[52][53] and various species of insects. Insect-inspired menus can be found at a number of restaurants in Khuong Thuong village, Hanoi.[54] The signature dishes at these restaurant are those containing processed ant-eggs, often in the culinary styles of Thai people or Vietnam's Muong and Tay ethnic people.[55] Dog eating used to be popular in Hanoi in 1990s and early 2000s but is now dying out quickly due to strong objections.

Education

Hanoi, as the capital of French Indochina, was home to the first Western-style universities in Indochina, including: Indochina Medical College (1902) – now Hanoi Medical University, Indochina University (1904) – now Hanoi National University (the largest), and École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de l'Indochine (1925) – now Hanoi University of Fine Art.

After the Communist Party of Vietnam took control of Hanoi in 1954, many new universities were built, among them, Hanoi University of Technology, still the largest technical university in Vietnam. Recently ULIS (University of Languages and International Studies) was rated as one of the top universities in south-east Asia for languages and language studies at the undergraduate level.[56] Other universities that are not part of Vietnam National University or Hanoi University include Hanoi School for Public Health and Hanoi School of Agriculture and University of Transport and Communications.

Hanoi is the largest center of education in Vietnam. It is estimated that 62% of the scientists in the whole country are living and working in Hanoi.[57] Admissions to undergraduate study are through entrance examinations, which are conducted annually and open to everyone (who has successfully completed his/her secondary education) in the country. The majority of universities in Hanoi are public, although in recent years a number of private universities have begun operation. Thăng Long University, founded in 1988, by Vietnamese mathematics professors in Hanoi and France[58] was the first private university in Vietnam. Because many of Vietnam's major universities are located in Hanoi, students from other provinces (especially in the northern part of the country) wishing to enter university often travel to Hanoi for the annual entrance examination. Such events usually take place in June and July, during which a large number of students and their families converge on the city for several weeks around the intense examination period. In recent years, these entrance exams have been centrally coordinated by the Ministry of Education, but entrance requirements are decided independently by each university.

Although there are state owned kindergartens, there are also many private ventures that serve both local and international needs. Pre-tertiary (elementary and secondary) schools in Hanoi are generally state run, but there are also some independent schools. Education is equivalent to the K–12 system in the U.S., with elementary school between grades 1 and 5, middle school (or junior high) between grades 6 and 9, and high school from grades 10 to 12.

Education levels are much higher within the city of Hanoi in comparison to the suburban areas outside the city. About 33.8% of the labor force in the city has completed secondary school in contrast to 19.4% in the suburbs.[30] 21% of the labor force in the city has completed tertiary education in contrast to 4.1% in the suburbs.[30]

Reform

Country-wide educational change is difficult in Vietnam, due to the restrictive control of the government on social and economic development strategies.[59] According to Hanoi government publications, the national system of education was reformed in 1950, 1956 and 1970.[59] It was not until 1975 when the two separate education systems of the former North and South Vietnam territories became unified under a single national system.[59] In Hanoi in December 1996, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam stated that: "To carry out industrialization and modernization successfully, it is necessary to develop education and training strongly [and to] maximize human resources, the key factor of fast and sustained development."[59]

Transport

Hanoi is served by Noi Bai International Airport, located in the Soc Son District, approximately 15 km (9 mi) north of Hanoi. The new international terminal (T2), designed and built by Japanese contractors, opened in January 2015 and is a big facelift for Noibai International Airport. In addition, a new highway and the new Nhat Tan cable-stay bridge connecting the airport and the city center opened at the same time, offering much more convenience than the old road (via Thanglong bridge). Taxis are plentiful and usually have meters, although it is also common to agree on the trip price before taking a taxi from the airport to the city centre.

Hanoi is also the origin or departure point for many Vietnam Railways train routes in the country. The Reunification Express (tàu Thống Nhất) runs from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City from Hanoi station (formerly Hang Co station), with stops at cities and provinces along the line. Trains also depart Hanoi frequently for Hai Phong and other northern cities. The Reunification Express line was established during French colonial rule and was completed over a period of nearly forty years, from 1899 to 1936.[60] The Reunification Express between Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City covers a distance of 1,726 km (1,072 mi) and takes approximately 33 hours.[61] As of 2005, there were 278 stations on the Vietnamese railway network, of which 191 were located along the North-South line.

The main means of transport within Hanoi city are motorbikes, buses, taxis, and a rising number of cars. In recent decades, motorbikes have overtaken bicycles as the main form of transportation. Cars however are probably the most notable change in the past five years as many Vietnamese people purchase the vehicles for the first time. The increased number of cars are the main cause gridlock as roads and infrastructure in the older parts of Hanoi were not designed to accommodate them.[62] On 4 July 2017, the Hanoi government voted to ban motorbikes entirely by 2030, in order to reduce pollution, congestion, and encourage the expansion and use of public transport.[63]

There are two metro lines under construction in Hanoi now, as part of the master plan for the future Hanoi Metro system.[64] The first line is expected to be operational in 2018, and the second in 2021.

Persons on their own or traveling in a pair who wish to make a fast trip around Hanoi to avoid traffic jams or to travel at an irregular time or by way of an irregular route often use "xe ôm" (literally, "hug bike"). Motorbikes can also be rented from agents within the Old Quarter of Hanoi, although this falls inside a rather grey legal area.[65]

Sports

There are several gymnasiums and stadiums throughout the city of Hanoi. The biggest ones are Mỹ Đình National Stadium (Lê Đức Thọ Boulevard), Quan Ngua Sporting Palace (Văn Cao Avenue), Hanoi Aquatics Sports Complex and Mỹ Đình Indoor Athletics Gymnasium. The others include Hà Nội Stadium (also known as Hàng Đẫy stadium). The third Asian Indoor Games were held in Hanoi in 2009. The others are Hai Bà Trưng Gymnasium, Trịnh Hoài Đức Gymnasium, Vạn Bảo Sports Complex.

Health care and other facilities

Some medical facilities in Hanoi:

- Bạch Mai Hospital

- Viet Duc Hospital

- Saint Paul Hospital

- 108 Hospital

- Hôpital Français de Hanoi

- International SOS

- Hanoi Medical University Hospital

- Thanh Nhan Hospital

- Vinmec International Hospital

- Viet Phap Hospital

- Thu Cuc General Hospital

- K Hospital

- Medlatech Hospital

International relations

Hanoi is a member of the Asian Network of Major Cities 21 and the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group.

Twin towns and sister cities

Hanoi is twinned with:

Image gallery

Tháp Bút (Pen Tower) with a phrase "Tả thanh thiên" (meaning "Write on the sky") next to Hoàn Kiếm Lake (2007)

Tháp Bút (Pen Tower) with a phrase "Tả thanh thiên" (meaning "Write on the sky") next to Hoàn Kiếm Lake (2007).jpg) Thê Húc Bridge on Hoàn Kiếm Lake

Thê Húc Bridge on Hoàn Kiếm Lake Presidential Palace, Hanoi (formerly Place of The Governor-General of French Indochina)

Presidential Palace, Hanoi (formerly Place of The Governor-General of French Indochina).jpg) Hanoi Opera House modeled on the Palais Garnier in Paris

Hanoi Opera House modeled on the Palais Garnier in Paris Museum of Vietnamese History in Hanoi, formerly the first École française d'Extrême-Orient

Museum of Vietnamese History in Hanoi, formerly the first École française d'Extrême-Orient

The St-Joseph Cathedral

The St-Joseph Cathedral National Museum of Fine Art

National Museum of Fine Art National Assembly building

National Assembly building

Lotte Center Hanoi in western Ba Đình

Lotte Center Hanoi in western Ba Đình

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

References

- 1 2 Statistical Handbook of Vietnam 2014 Archived 6 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine., General Statistics Office Of Vietnam

- ↑ http://dantri.com.vn/doi-song/canh-sinh-hoat-kho-tin-o-nhung-con-ngo-khong-bao-gio-thay-mat-troi-20170805083728359.htm

- ↑ "Hanoi". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Hanoi". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà (1997), Vietnamese: Tiếng Việt không son phấn, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, ISBN 1-55619-733-0

- ↑ LE-QUYEN LE (18 May 2010). "Commemorating 1,000 Years of the Founding of Hanoi". Vietnam Talking Points. Vietnam Talking Points. Archived from the original on 13 June 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ Con Giang (9 January 2012). "Lands named "dragon"". Tuổi Trẻ. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ↑ Ray, Nick; et al. (2010), "Co Loa Citadel", Vietnam, Lonely Planet, p. 123, ISBN 9781742203898, archived from the original on 2 April 2015 .

- 1 2 "Historical stages of Thang Long- Hanoi – 1000 Years Thang Long (VietNamPlus)". En.hanoi.vietnamplus.vn. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Logan, William S. (2005). "The Cultural Role of Capital Cities: Hanoi and Hue, Vietnam". Pacific Affairs. 78 (4): 559–575. JSTOR 40022968.

- ↑ "Country files (GNS)". National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- 1 2 "Hơn 90% đại biểu Quốc hội tán thành mở rộng Hà Nội". Dantri. Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ↑ Peel, M. C. and Finlayson, B. L. and McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11: 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "KHÁI QUÁT VỀ HÀ NỘI" (in Vietnamese). Hanoi.gov.vn. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Vietnam Building Code Natural Physical & Climatic Data for Construction" (PDF) (in Vietnamese). Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "ПОГОДА в Ханое" [Weather in Hanoi] (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ↑ "Hà Nội nóng kỷ lục 41,5 độ" (in Vietnamese). danviet.vn. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ↑ "Climate Ha Noi March - 1988". tutiempo.net. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ "Climate Ha Noi April - 1982". tutiempo.net. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ "THỜI TIẾT HÀ NỘI" (in Vietnamese). nchmf.gov.vn. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 . 31 December 2017 http://thongkehanoi.gov.vn/a/nien-giam-thong-ke-tom-tat-2017-1532053197/. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). Retrieved 20 July 2018. Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City are topping the world's highest economic growth cities in 2008-2025" (PDF). PricewaterhouseCoopers. 10 November 2009.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ "'Tram hoa' doanh nghiep dua no". VnExpress. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007.

- ↑ "NLĐO – Bat dong san Ha Noi soi dong ~ Bất động sản Hà Nội sôi động – KINH TẾ – TIÊU DÙNG". Archived from the original on 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lincoln, Martha (2008). "Report from the field: street vendors and the informal sector in Hanoi". Dialectical Anthropology. 32 (3): 261–265. JSTOR 29790838.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 FORBES, DEAN (2001). "Socio-Economic Change and the Planning of Hanoi". Built Environment (1978-). 27 (2): 68–84. JSTOR 23287513.

- ↑ Turner, Shoenberger, Sarah, Laura (June 2011). "Street Vendor Livelihoods and Everyday Politics in Hanoi, Vietnam: The Seeds of a Diverse Economy?". Urban Studies. 49: 1027–1044 – via Sage journals.

- ↑ Kiem, Nguyen Manh (1996). "Strategic Orientation for Construction and Development of Hanoi, Vietnam". Ambio. 25 (2): 108–109. JSTOR 4314433.

- ↑ Van Arkadie, Brian; Mallon, Raymond, eds. (2004). Viet Nam — a Transition Tiger?. ANU Press. pp. 224–234. ISBN 0731537505. JSTOR j.ctt2jbjk6.22.

- ↑ "VIETNAM IN THE ERA OF DOI MOI: Issue-Oriented Organizations and Their Relationship to the Government on JSTOR". doi:10.1525/as.2003.43.6.867.pdf. JSTOR 10.1525/as.2003.43.6.867.

- ↑ "VIETNAM IN THE ERA OF DOI MOI: Issue-Oriented Organizations and Their Relationship to the Government on JSTOR". doi:10.1525/as.2003.43.6.867.pdf. JSTOR 10.1525/as.2003.43.6.867.

- ↑ "VIETNAM IN THE ERA OF DOI MOI: Issue-Oriented Organizations and Their Relationship to the Government on JSTOR". doi:10.1525/as.2003.43.6.867.pdf. JSTOR 10.1525/as.2003.43.6.867.

- ↑ "VIETNAM IN THE ERA OF DOI MOI: Issue-Oriented Organizations and Their Relationship to the Government on JSTOR". doi:10.1525/as.2003.43.6.867.pdf. JSTOR 10.1525/as.2003.43.6.867.

- ↑ "VIETNAM IN THE ERA OF DOI MOI: Issue-Oriented Organizations and Their Relationship to the Government on JSTOR". doi:10.1525/as.2003.43.6.867.pdf. JSTOR 10.1525/as.2003.43.6.867.

- ↑ "The quick look at Hanoi". Vietnam National Administration of Tourism. Archived from the original on 9 February 2007.

- ↑ "Introduction to Hanoi". The New York Times from Frommer's. 20 November 2006. Archived from the original on 19 January 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ↑ 'Hanoi: Biography of a City' by William S. Logan, University of Washington Press 2000 ISBN 0295980141

- ↑ 'A Scholar's Memoirs of the 36 Streets', in: Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David: Vietnam Past and Present: The North (History and culture of Hanoi and Tonkin). Chiang Mai. Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006DCCM9Q.

- ↑ Pinkowski, Jennifer (16 October 2007). "Thăng Long the ancient city underneath Hanoi". New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ↑ Michael G. Vann, "Building Whiteness on the Red River: Race, Power, and Urbanism in Paul Doumer's Hanoi, 1897-1902," Historical Reflections/Réflexions Historiques, 2007

- ↑ Michael G. Vann, "Of Rats, Rice, and Race: The Great Hanoi Rat Massacre, an Episode in French Colonial History," French Colonial History, May 2003

- ↑ Plevin, Julia. "Notes on Hanoi, Vietnam". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ↑ "Detailed results and winners of the online Smart Travel Asia Best in Travel Poll 2009". Smarttravelasia.com. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ↑ "Best Street Food | Vietnamese Pho | Peruvian Food". Globalpost.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ↑ "Nguyen Van Duc Snake Restaurant". TNH Hanoi. TNH. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ Will Chase (2005). "Culinary Adventures in Hanoi". Will Chase Arts. Will Chase. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ VietNamNet Bridge (1 June 2007). "Insect food in Hanoi". VietNamNet Bridge. VietNamNet Bridge. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ "Caught the bug yet?". Restaurants in Hanoi. Restaurants in Hanoi. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ "Vietnam National University, Hanoi". Top Universities. 8 December 2012. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Hanoi – The capital of Vietnam: Preface". Hanoi City People's Committee. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ↑ Viet Nam News (9 April 1998). "Viet Nam News". Vietnamnews.vnagency.com.vn. Archived from the original on 14 December 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Duggan, Stephen (2001). "Educational Reform in Viet Nam: A Process of Change or Continuity?". Comparative Education. 37 (2): 193–212. JSTOR 3099657.

- ↑ "Socialist Republic of Viet Nam: Greater Mekong Subregion Kunming–Hai Phong Transport Corridor: Yen Vien–Lao Cai Railway Upgrading Project" (PDF). Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors: Project Number: 39175: Asian Development Bank. Asian Development Bank. November 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ Mark Smith (19 May 2012). "A fast, vast steel spine". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ Hans-Heinrich Bass; Thanh Trung Nguyen (March 2013). "Imminent gridlock". dandc.eu. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013.

- ↑ "Hanoi plan to ban motorbikes by 2030 to combat pollution". BBC News. 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ "Getting Around Hanoi". Frommer's. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ Ilia Lobster (9 September 2009). "Astana-Hanoi: horizons of cooperation". KazPravda.kz. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Kardeş Kentleri Listesi ve 5 Mayıs Avrupa Günü Kutlaması [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Turkish). Ankara Büyükşehir Belediyesi – Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ "Miasta partnerskie Warszawy – Strona 4". um.warszawa.pl. Biuro Promocji Miasta. 4 May 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ↑ "Hanoi strengthens ties with Ile-de-France". Voice of Vietnam. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ↑ "Hanoi Days in Moscow help sister cities". Vbusinessnews.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009.

- ↑ "National Commission for Decentralised cooperation". Délégation pour l'Action Extérieure des Collectivités Territoriales (Ministère des Affaires étrangères) (in French). Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). Retrieved 26 December 2013. - ↑ "International Cooperation: Sister Cities". Seoul Metropolitan Government. www.seoul.go.kr. Archived from the original on 10 December 2007. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- ↑ "Seoul -Sister Cities [via WayBackMachine]". Seoul Metropolitan Government (archived 2012-04-25). Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ↑ "Sister Cities". Phnompenh.gov.kh. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Thủ tướng Nguyễn Tấn Dũng hội kiến Tổng thống Seychelles". BÁO ĐIỆN TỬ CỦA CHÍNH PHỦ NƯỚC CỘNG HÒA XÃ HỘI CHỦ NGHĨA VIỆT NAM. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

Bibliography

- Boudarel, Georges (2002). Hanoi: City Of The Rising Dragon. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-7425-1655-5.

- Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David: Vietnam Past and Present: The North (History and culture of Hanoi and Tonkin). Chiang Mai. Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006DCCM9Q.

- Logan, William S. (2001). Hanoi: Biography of a City. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-98014-1.

External links

- Official Site of Hanoi Government

- An article in New York Times about Hanoi