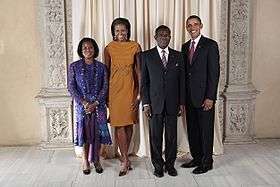

Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo

| Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd President of Equatorial Guinea | |

|

Assumed office 3 August 1979 | |

| Prime Minister |

Cristino Seriche Bioko Silvestre Siale Bileka Ángel Serafín Seriche Dougan Cándido Muatetema Rivas Miguel Abia Biteo Boricó Ricardo Mangue Obama Nfubea Ignacio Milam Tang Vicente Ehate Tomi Francisco Pascual Obama Asue |

| Vice President |

Florencio Mayé Elá (1979-1982) Ignacio Milam Tang (2012-2016) Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue (2016-) |

| Preceded by | Francisco Macías Nguema |

| Chairperson of the African Union | |

|

In office 31 January 2011 – 29 January 2012 | |

| Preceded by | Bingu wa Mutharika |

| Succeeded by | Yayi Boni |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

5 June 1942 Acoacán, Spanish Guinea (now Equatorial Guinea) |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouse(s) | Constancia Mangue |

| Children | Teodoro |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Equatorial Guinea |

|

| Chronological |

|

|

Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo (Spanish pronunciation: [te.o.ˈðo.ɾo o.ˈβjãŋɡ ˈŋ.ɡe.ma m.ˈba.so.go]; born 5 June 1942) is an Equatoguinean politician who has been President of Equatorial Guinea since 1979. He ousted his uncle, Francisco Macías Nguema, in an August 1979 military coup and has overseen Equatorial Guinea's emergence as an important oil producer, beginning in the 1990s. Obiang was Chairperson of the African Union from 31 January 2011 to 29 January 2012. He is the second longest-serving non-royal national leader in the world.[1]

Obiang has been widely accused of corruption and abuse of power. In marked contrast to the trend toward democracy in most of Africa, Equatorial Guinea is currently a dominant-party state, in which Obiang's Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea (PDGE) holds virtually all governing power in the nation. The constitution provides Obiang sweeping powers, including the right to rule by decree, effectively making his government a legal dictatorship.

Early life

Born into the Esanguii clan in Akoakam, son of Santiago Nguema Eneme and María Mbasogo Ngui. Obiang joined the military during Equatorial Guinea's colonial period and attended the military academy in Zaragoza, Spain. He achieved the rank of lieutenant after his uncle, Francisco Macías Nguema, was elected the country's first president. Under Macías, Obiang held various positions, including governor of Bioko and leader of the National Guard.[2] He was also head of Black Beach Prison, notorious for severely torturing its inmates.[3]

Presidency

After Macías ordered the murders of several members of the family they shared, including Obiang's brother, Obiang and others in Macías' inner circle feared the president had become insane. Obiang overthrew his uncle on 3 August 1979 in a bloody coup d'état,[2] and placed him on trial for his actions, including the genocide of the Bubi people, over the previous decade. Macías was sentenced to death and executed by firing squad on 29 September 1979. A new Moroccan presidential guard was required to form the firing squad, because local soldiers feared his alleged magical powers.[4]

Obiang declared that the new government would make a fresh start from Macías' brutal and repressive régime. He granted amnesty to political prisoners, and ended the previous régime's system of forced labor. However, he made virtually no mention of his own role in the atrocities committed under his uncle's rule.[2]

New constitution

The country nominally returned to civilian rule in 1982, with the enactment of a slightly less authoritarian constitution. At the same time, Obiang was elected to a seven-year term as president; he was the only candidate. He was reelected in 1989, again as the only candidate. After other parties were nominally allowed to organize in 1992, he was reelected in 1996 and 2002 with 98 percent of the vote[5] in elections condemned as fraudulent by international observers.[6] In 2002, for instance, at least one precinct was recorded as giving Obiang 103 percent of the vote.[3]

He was reelected for a fourth term in 2009 with 97% of the vote, again amid accusations of voter fraud and intimidation,[7] beating opposition leader Plácido Micó Abogo.[8]

Obiang's rule was at first considered more humane than that of his uncle. By some accounts, however, it has become increasingly brutal, and has bucked the larger trend toward greater democracy in Africa. Most domestic and international observers consider his régime to be one of the most corrupt, ethnocentric, oppressive and undemocratic states in the world. Equatorial Guinea is essentially a one-party state dominated by Obiang's Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea (PDGE). The constitution grants Obiang sweeping powers, including the power to rule by decree.

Although opposition parties were legalized in 1992, the legislature remains dominated by the PDGE, and there is almost no opposition to Obiang's decisions within the body. There have never been more than eight opposition deputies in the chamber. At present, all of the deputies but one either belong to the PDGE or is allied with it. For all intents and purposes, Obiang holds all governing power in the nation.

The opposition is barely tolerated; indeed, a 2006 article in Der Spiegel quoted Obiang as asking, "What right does the opposition have to criticize the actions of a government?"[3] The opposition is severely hampered by the lack of a free press as a vehicle for their views. There are no newspapers and all broadcast media are either owned outright by the government or controlled by its allies.

International relations

United States

Equatorial Guinea's relations with the United States cooled in 1993, after Ambassador John E. Bennett was accused of practicing witchcraft at the graves of 10 British airmen who were killed when their plane crashed there during World War II. Bennett left after receiving a death threat at the U.S. Embassy in Malabo in 1994.[9][10] In his farewell address, he publicly named the government's most notorious torturers, including Equatorial Guinea's then-current Minister of National Security, Manuel Nguema Mba, another Obiang uncle. No new envoy was appointed, and the embassy was closed in 1996, leaving its affairs to be handled by the embassy in neighboring Cameroon.

Things turned around for the Obiang regime after the terrorist attacks in 2001 on New York and Washington, after which the United States re-prioritized its dealings with key African states. On 25 January 2002, the Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies, a neoconservative Israeli-based think tank, sponsored a forum on "African Oil: A Priority for U.S. National Security and African Development" at the University Club in Washington, D.C. It concluded that "West African oil... can help stabilize the Middle East, end Muslim terror, and secure a measure of energy security".[11] Speaking at the IASPS forum, Assistant Secretary of State for Africa Walter H. Kansteiner said, "African oil is of national strategic interest to us, and it will increase and become more important as we move forward."[11]

In a lengthy state visit from March to April 2006, President Obiang sought to reopen the closed embassy in the US, saying that "the lack of a U.S. diplomatic presence is definitely holding back economic growth."[12] President Obiang was warmly greeted by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, who called him a "good friend".[13] Public relations company Cassidy & Associates may have been partially responsible for the change in tone between Obiang and the United States government. Since 2004, Cassidy had been employed by the dictator's government at a rate of at least $120,000 a month.[14]

By October 2006, however, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee had raised concerns about the proposal to build the new embassy on land owned by Obiang, whom the United Nations Commission on Human Rights accused of directly overseeing the torture of opponents.[3] The new embassy chancery opened in 2013.[15]

Controversy

In July 2003, state-operated radio declared Obiang "the country's god" with "all power over men and things." It added that the president was "in permanent contact with the Almighty" and "can decide to kill without anyone calling him to account and without going to hell." He personally made similar comments in 1993. Macías had also proclaimed himself a god.[16]

Obiang has encouraged his cult of personality by ensuring that public speeches end in well-wishing for himself rather than for the republic. Many important buildings have a presidential lodge, many towns and cities have streets commemorating Obiang's coup against Macías, and many people wear clothes with his face printed on them.[17][18]

Like his predecessor and other African dictators such as Idi Amin and Mobutu Sese Seko, Obiang has assigned himself several creative titles. Among them are "gentleman of the great island of Bioko, Annobón and Río Muni."[19] He also refers to himself as El Jefe (the boss).[20]

In 2008, American journalist Peter Maass called Obiang Africa's worst dictator, worse than Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe.[21]

Since the downfall of Muammar Gaddafi in October 2011, Obiang has become the world's second longest-ruling non-royal head of state.

In an October 2012 interview on CNN, Christiane Amanpour asked Obiang whether he would step down at the end of the then-current term (2009–2016) since he had been reelected at least four times in his reign of over thirty years. In his response, Obiang categorically refused to step down at the end of the term despite the term limits in the 2011 constitution.[22]

Abuses

Abuses under Obiang have included "unlawful killings by security forces; government-sanctioned kidnappings; systematic torture of prisoners and detainees by security forces; life-threatening conditions in prisons and detention facilities; impunity; arbitrary arrest, detention, and incommunicado detention."[23]

Wealth

Forbes magazine has said that Obiang, with a net worth of US$600 million, is one of the world's wealthiest heads of state.[24]

In 2003, Obiang told his citizenry that he felt compelled to take full control of the national treasury in order to prevent civil servants from being tempted to engage in corrupt practices. Obiang then deposited more than half a billion dollars into more than sixty accounts controlled by himself and his family at Riggs Bank in Washington, D.C., leading a U.S. federal court to fine the bank $16 million for allowing him to do so.[25] A United States Senate investigation in 2004 found that the Washington-based Riggs Bank had taken $300 million in payments on behalf of Obiang from Exxon Mobil and Hess Corporation.[26]

In 2008, the country became a candidate for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative – an international project meant to promote openness about government oil revenues – but never qualified and missed the April 2010 deadline.[26] Transparency International includes Equatorial Guinea on its list of twelve most corrupt states.[26][27]

Beginning in 2007 Obiang and several other African state leaders came under investigation for corruption and fraudulent use of funds. He was suspected of using public funds to finance private mansions and other luxuries for both himself and his family. He and his son, in particular, owned several properties and supercars in France. Several complaints were also filed in US courts against Obiang’s son. Attorneys stressed that the funds appropriated by the Obiangs were taken quite legally under Equatoguinean laws, even though those laws might not agree with international standards.[28]

The US Department of Justice alleged that Obiang and his son had appropriated hundreds of millions of dollars through corruption.[29] In 2011 and early 2012, many assets were seized from Obiang and his son by the French and American governments, including mansions, wine collections, and supercars. The United States, France and Spain have all investigated the Obiang family's use of public funds.[29] The corruption investigation is ongoing.[28][30]

Obiang, his cabinet and his family allegedly have received billions in undisclosed oil revenue each year from the nation's oil production. Marathon Oil purchased land from Abayak, Obiang's personal investment vehicle, for more than $2 million; in June 2004 the sale was pending but Marathon had already made a $611,000 first payment with a check made out to Obiang. Marathon also was involved in a joint venture to operate two gas plants with GEOGAM, a quasi-state firm in which Abayak controlled a 75% stake.[31]

Although the cabinet has made moderate increases to social spending, these remain far overshadowed by the spending on, for instance, presidential palaces.[29] In addition, the Obiang administration has been characterized by harassment of dissenters and foreign officials seeking to report on conditions.[32]

Obiang filed a libel lawsuit in a French court against an organization he believed was demeaning his image by saying that his government had committed such acts, but the case was dismissed.[29][33]

Obiang has made several pledges to commit to open governance, reduce corruption, increase transparency, and improve the quality of life and uphold the basic freedoms of his citizens. Critics say that Obiang’s government has made very little progress towards this goal, however.[29][32][34] Several international groups have called for Obiang to:

- increase fiscal transparency and accountability by publishing all government revenues, and conducting and publishing annual audits of government accounts, including those abroad, and forcing officials to declare assets

- Disclose natural resource revenues

- Greatly increase spending alleviation of poverty

- Uphold political freedoms and rights

- Allow judicial practices to meet international standards

- Cease harassing and hindering his critics

- Allow foreign inspectors and groups to travel freely, unhindered and unharassed.[29][32]

The US Justice Department has alleged that Obiang’s son also extorted funds from lumber and construction companies by inflating contractor payments by as much as 500%, then funnelled the funds into a private accounts for his own use. Obiang and his cabinet have defended Kiki, as his son is known. Lawyers uphold his innocence in both US and French courts, saying he received the funds legally though legitimate business enterprises.[29][35]

Shortly after the emergence of these allegations, Obiang named his son Equatorial Guinea’s deputy permanent delegate to UNESCO, possibly giving him diplomatic immunity from prosecution. Obiang has created an independent audit task force to review the expenditures and financials of public figures in the government, screen for corruption, and increase financial transparency. The head of this task force, however, was appointed by Obiang himself.[29]

Finances

Obiang had a close relationship with the Washington DC-based Riggs Bank. He is said to have been welcomed by top Riggs officials, who held a luncheon in his honor.[36] Publicity regarding this relationship would later contribute to the downfall of Riggs.[37]

On 10 November 2010, the Supreme Court of France ruled that a complaint filed by Transparency International in France on 2 December 2008 was admissible to the court system there. The decision allowed the appointment of an investigating judge and a judicial inquiry into claims that Obiang used state funds to purchase private property in France.[38]

A 2010 article published in Forbes magazine suggested that Obiang gathered roughly $700 million of the country's wealth in US bank accounts.[39]

Cannibalism claims

Nguema's opponents have accused him of cannibalism in reference to claims that he has consumed parts of his enemies in order to exhibit power.[40]

Personal life

Obiang reportedly favours his son Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue to succeed him.[41]

Honours

References

- ↑ "Equatorial Guinea: Palace in the jungle: Ordinary folk see none of their country's riches". The Economist. 12 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 Gardner, Dan (6 November 2005). "The Pariah President: Teodoro Obiang is a brutal dictator responsible for thousands of deaths. So why is he treated like an elder statesman on the world stage?". The Ottawa Citizen (reprint: dangardner.ca). Archived from the original on 12 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Alexander Smoltczyk (28 August 2006). "Rich in Oil, Poor in Human Rights: Torture and Poverty in Equatorial Guinea". Der Spiegel.

- ↑ Steve Bloomfield, (13 May 2007). "Teodoro Obiang Nguema: A brutal, bizarre jailer". The Independent. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ↑ Bloomfield, Steve (13 May 2007) "Teodoro Obiang Nguema: A brutal, bizarre jailer" The Independent, last accessed 21 October 2010

- ↑ United States Central Intelligence Agency (2009) CIA World Factbook 2010 Skyhorse Pub Co Inc., New York, page 214, ISBN 978-1-60239-727-9

- ↑ Tran, Mark (30 November 2009) "President Nguema of Equatorial Guinea on course to extend three-decade rule" The Guardian, last accessed 21 October 2010

- ↑ "Nguema wins re-election". Iol.co.za. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ "A Touch of Crude". Mother Jones. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ Douglas Farah (May 14, 2001). "A Matter of 'Honor' In a Jungle Graveyard". Washington Post. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- 1 2 Archived 15 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Larry Luxner (August 2001). "Equatorial Guinea Goes from Rags to Riches With Oil Boom". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2007; Larry Luxner is a contributing writer for The Washington Diplomat.

- ↑ Archived 14 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kurlantzick, Joshua (May 2007). "Putting Lipstick on a Dictator". Mother Jones. Retrieved 22 August 2007.

- ↑ "United States Dedicates New U.S. Embassy in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea". U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ "Equatorial Guinea's 'God'". BBC. 26 July 2003. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ Maass, Peter (2005) "A Touch of Crude" Mother Jones 30 (1): pp. 48–89

- ↑ Silverstein, Ken (2010) "Saturday Lagniappe: UNESCO for Sale: Dictators allowed to buy their own prizes, for the right price" Petroleumworld, originally published by Harpers Magazine, 2 June 2010, archived at Freezepage

- ↑ "In his address at UNESCO's annual meeting of governments on 30 October 2007 the "Gentleman of the great island of Bioko, Annobón and Río Muni", "a god who is 'in permanent contact with the Almighty'” and "can decide to kill without anyone calling him to account and without going to hell" His Excellence, President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, ..." Kabanda (3 October 2010) "Money for good causes: does the source matter?" Sunday Times (Rwanda), premium content that requires login, last accessed 21 October 2010

- ↑ Staff (28 September 2010) "Africa's Worst Dictators: Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo" Archived 23 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. MSN News (South Africa), archived at Freezepage

- ↑ Maass, Peter (24 June 2008). "Who's Africa's Worst Dictator?". Slate. The Washington Post Company. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

But Mugabe may not be Africa's worst. That prize arguably goes to Teodoro Obiang, the ruler of Equatorial Guinea

- ↑ "Interview with President Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea". Transcripts.cnn.com.

- ↑ United States State Department (25 February 2009) "2008 Human Rights Report: Equatorial Guinea", archived at Freezepage

- ↑ "Fortunes of Kings, Queens And Dictators". Forbes. 5 May 2006. and part of a slideshow

- ↑ Ken Silverstein. "Oil Boom Enriches African Ruler: While the people of Equatorial Guinea live on a dollar a day, sources say their leader controls more than $300 million in a Washington bank". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 22 January 2003.

- 1 2 3 "Equatorial Guinea profile". BBC News. 24 January 2012.

- ↑ "First launched in 1995, the Corruption Perceptions Index has been widely credited with putting the issue of corruption on the international policy agenda". Transparency International.

- 1 2 de la Baume, Maia (23 August 2012). "A French Shift on Africa Strips a Dictator's Son of his Treasures". New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "DC Mee. ting Set with President Obiang as Corruption Details Emerge". Global Witness. 15 June 2012.

- ↑ Alford, Roger (18 October 2011). "United States v. One White, Crystal-Covered "Bad Tour" Glove". Huffington Post.

- ↑ Penter Maass (2005). "A Touch of Crude: American bankers handled his loot. Oil companies play by his rules. The Bush administration woos him. How the pursuit of oil is propping up the West African dictatorship of Teodoro Obiang". Mother Jones.

- 1 2 3 Attiah, Karen (7 August 2012). "How an African Dictator Pays for Influence". Huffington Post.

- ↑ "Equatorial Guinea's President, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, Skips FAO Address". Huffington Post. 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Shook, David (28 May 2013). "Choosing Our Oil Over Their Democracy: Elections as Farce in Equatorial Guinea". Huffington Post.

- ↑ Nsehe, Mfonobong (7 July 2011). "An African Dictator's Son And His Very Lavish Toys". Forbes.

- ↑ Montgomery, David; Kathleen Day (17 July 2004). "Critics Say Allbritton Ruined Bank He Loved". Washington Post. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ↑ Gurulé, Jimmy (2008) "Chapter 11: Private causes of action: using the civil justice system to hold terrorist financiers accountable" Unfunding terror: the legal response to the financing of global terrorism Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, England, footnote 10, page 356; ISBN 978-1-84542-962-1

- ↑ Newstime Africa, 22 November 2010.

- ↑ "Unesco suspends Obiang prize". Al Jazeera. 21 October 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ↑ Norman, Joshua. "The world's enduring dictators: Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, Equatorial Guinea". CBS. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Chris McGreal; Dan Glaister (10 November 2006). "The tiny African state, the president's playboy son and the $35m Malibu mansion". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Teodoro Obiang. |

- President Obiang's address to the 63rd session of the United Nations General Assembly, 25 September 2008

- Honorary Consul for Equatorial Guinea

- Who's Africa's Worst Dictator? Hint: It's probably not Robert Mugabe Slate.com

- "Torture and Poverty in Equatorial Guinea", Alexander Smoltczyk, Der Spiegel, 28 August 2006

- Amidst Poverty, Equatorial Guinea Builds Lavish City to Host African Union — video report by Democracy Now!

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Francisco Macías Nguema |

President of Equatorial Guinea 1979–present |

Incumbent |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Bingu wa Mutharika |

Chairperson of the African Union 2011–2012 |

Succeeded by Yayi Boni |