North Korea–South Korea relations

| |

North Korea |

South Korea |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic Mission | |

| Committee for the Peaceful Reunification of the Fatherland, Pyongyang | Ministry of Unification, Seoul |

| South Korean name | |

| Hangul | 남북 관계 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 南北關係 |

| Revised Romanization | Nambuk gwan-gye |

| McCune–Reischauer | Nampuk kwan'gye |

| North Korean name | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 북남관계 |

|---|---|

| Hancha | 北南關係 |

| Revised Romanization | Bungnam gwangye |

| McCune–Reischauer | Pungnam kwan'gye |

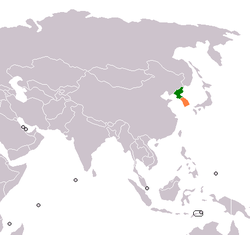

The political, commercial, diplomatic, and military interactions between North Korea and South Korea began in 1945 with the division of Korea at the end of World War II. Since then, North and South Korea have been locked in a conflict which erupted into open warfare in 1950 with the Korean War.

In 2018, beginning with North Korea's participation in the Winter Olympics in South Korea, the relationship has seen a major diplomatic breakthrough and become significantly warmer. In April 2018, the two countries signed the Panmunjeom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification of the Korean Peninsula.[1] In 2018, a majority of South Koreans approved the new relationship.[2]

Division of Korea

The Korean peninsula had been occupied by Japan from 1910. On August 9, 1945, in the closing days of World War Two, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and advanced into Korea. Though the Soviet declaration of war had been agreed by the Allies at the Yalta Conference, the US government became concerned at the prospect of all of Korea falling under Soviet control. The US government therefore requested Soviet forces halt their advance at the 38th parallel north, leaving the south of the peninsula, including the capital, Seoul, to be occupied by the US. This was incorporated into General Order No. 1 to Japanese forces after the Surrender of Japan on August 15. On August 24, the Red Army entered Pyongyang and established a military government over Korea north of the parallel. American forces landed in the south on September 8 and established the United States Army Military Government in Korea.[3]

The Allies had originally envisaged a joint trusteeship which would steer Korea towards independence, but most Korean nationalists wanted independence immediately.[4] Meanwhile, the wartime co-operation between the Soviet Union and the US deteriorated as the Cold War took hold. Both occupying powers began promoting into positions of authority Koreans aligned with their side of politics and marginalizing their opponents. Many of these emerging political leaders were returning exiles with little popular support.[5][6] In North Korea, the Soviet Union supported Korean Communists. Kim Il-sung, who from 1941 had served in the Soviet Army, became the major political figure.[7] Society was centralized and collectivized, following the Soviet model.[8] Politics in the South was more tumultuous, but the strongly anti-Communist Syngman Rhee emerged as the most prominent politician.[9]

The US government took the issue to the United Nations, which led to the formation of the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) in 1947. The Soviet Union opposed this move and refused to allow UNTCOK to operate in the North. UNTCOK organised a general election in the South, which was held on May 10, 1948.[10] The Republic of Korea was established with Syngman Rhee as President, and formally replaced the US military occupation on August 15. In North Korea, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea was declared on September 9, with Kim Il-sung, as prime minister. Soviet occupation forces left the North on December 10, 1948. US forces left the South the following year, though the US Korean Military Advisory Group remained to train the Republic of Korea Army.[11]

As a result, two antagonistic states emerged, with diametrically opposed political, economic, and social systems. Both opposing governments considered themselves to be the government of the whole of Korea, and both saw the division as temporary.[12][13] The DPRK proclaimed Seoul to be its official capital, a position not changed until 1972.[14]

Korean War

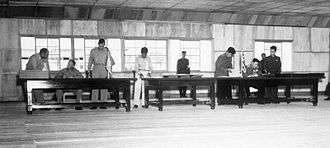

North Korea invaded the South on June 25, 1950, and swiftly overran most of the country. In September 1950 the United Nations force, led by the United States, intervened to defend the South, and advanced into North Korea. As they neared the border with China, Chinese forces intervened on behalf of North Korea, shifting the balance of the war again. Fighting ended on July 27, 1953, with an armistice that approximately restored the original boundaries between North and South Korea.[15] Syngman Rhee refused to sign the armistice, but reluctantly agreed to abide by it.[16] The armistice inaugurated an official ceasefire but did not lead to a peace treaty. It established the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a buffer zone between the two sides, that intersected the 38th parallel but did not follow it.[16] North Korea has announced that it will no longer abide by the armistice at least six times, in the years 1994, 1996, 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2013.[17][18]

Large numbers of people were displaced as a result of the war, and many families were divided by the reconstituted border. In 2007 it was estimated that around 750,000 people remained separated from immediate family members, and family reunions have long been a diplomatic priority for the South.[19]

Cold War

Competition between North and South Korea became key to decision-making on both sides. For example, the construction of the Pyongyang Metro spurred the construction of one in Seoul.[20] In the 1980s, the South Korean government built a 98m tall flagpole in its village of Daeseong-dong in the DMZ. In response, North Korea built a 160m tall flagpole in its nearby village of Kijŏng-dong.[21]

Tensions escalated in the late 1960s with a series of low-level armed clashes known as the Korean DMZ Conflict. During this time South Korea conducted covert raids on the North.[22][23][24] On January 21, 1968, North Koreans commandos attacked the South Korean Blue House. On December 11, 1969, a South Korean airliner was hijacked.

During preparations for US President Nixon's visit to China in 1972, South Korean President Park Chung-hee initiated covert contact with the North's Kim Il-sung.[25] In August 1971, the first Red Cross talks between North and South Korea were held.[26] Many of the participants were really intelligence or party officials.[27] In May 1972, Lee Hu-rak, the director of the Korean CIA, secretly met with Kim Il-sung in Pyongyang. Kim apologized for the Blue House Raid, denying he had approved it.[28] In return, North Korea's deputy premier Pak Song-chol made a secret visit to Seoul.[29] On July 4, 1972, the North-South Joint Statement was issued. The statement announced the Three Principles of Reunification: first, reunification must be solved independently without interference from or reliance on foreign powers; second, reunification must be realized in a peaceful way without use of armed forces against each other; finally, reunification transcend the differences of ideologies and institutions to promote the unification of Korea as one ethnic group.[26][30] It also established the first "hotline" between the two sides.[31]

North Korea suspended talks in 1973 after the kidnapping of South Korean opposition leader Kim Dae-jung by the Korean CIA.[25][32] Talks restarted, however, and between 1973 and 1975 there were 10 meetings of the North-South Coordinating Committee at Panmunjom.[33]

In the late 1970s, US President Jimmy Carter hoped to achieve peace in Korea. However, his plans were derailed because of the unpopularity of his proposed withdrawal of troops.[34]

In 1983, a North Korean proposal for three-way talks with the United States and South Korea coincided with the Rangoon assassination attempt against the South Korean President.[35] This contradictory behavior has never been explained.[36]

In September 1984, North Korea's Red Cross sent emergency supplies to the South after severe floods.[25] Talks resumed, resulting in the first reunion of separated families in 1985, as well as a series of cultural exchanges.[25][37] Goodwill dissipated with the staging of the US-South Korean military exercise, Team Spirit, in 1986.[38]

When Seoul was chosen to host the 1988 Summer Olympics, North Korea tried to arrange a boycott by its Communist allies or a joint hosting of the Games.[39] This failed, and the bombing of Korean Air Flight 858 in 1987 was seen as North Korea's revenge.[40] However, at the same time, amid a global thawing of the Cold War, the newly elected South Korean President Roh Tae-woo launched a diplomatic initiative known as Nordpolitik. This proposed the interim development of a "Korean Community", which was similar to a North Korean proposal for a confederation.[41] From September 4 to 7, 1990, high-level talks were held in Seoul, at the same time that the North was protesting about the Soviet Union normalizing relations with the South. These talks led in 1991 to the Agreement on Reconciliation, Non-Aggression, Exchanges and Cooperation and the Joint Declaration of the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.[42][43] This coincided with the admission of both North and South Korea into the United Nations.[44] Meanwhile, on March 25, 1991, a unified Korean team first used the Korean Unification Flag at the World Table Tennis Competition in Japan, and on May 6, 1991, a unified team competed at the World Youth Football Competition in Portugal.

There were limits to the thaw in relations, however. In 1989, Lim Su-kyung, a South Korean student activist who participated in the World Youth Festival in Pyongyang, was jailed on her return.[44]

Sunshine and shadow

The end of the Cold War brought economic crisis to North Korea and led to expectations that reunification was imminent.[45][46] North Koreans began to flee to the South in increasing numbers. According to official statistics there were 561 defectors living in South Korea in 1995, and over 10,000 in 2007.[47]

In December 1991 both states made an accord, the Agreement on Reconciliation, Non-Aggression, Exchange and Cooperation, pledging non-aggression and cultural and economic exchanges. They also agreed on prior notification of major military movements and established a military hotline, and to work on replacing the armistice with a "peace regime".[48][49][50]

In 1994, concern over North Korea's nuclear program led to the Agreed Framework between the US and North Korea.[51]

In 1998, South Korean President Kim Dae-jung announced a Sunshine Policy towards North Korea. Despite a naval clash in 1999, this led in June, 2000, to the first Inter-Korean summit, between Kim Dae-jung and Kim Jong-il.[52] As a result, Kim Dae-jung was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[53] The summit was followed in August by a family reunion.[37] In September, the North and South Korean teams marched together at the Sydney Olympics.[54] Trade increased to the point where South Korea became North Korea's largest trading partner.[55] Starting in 1998, the Mount Kumgang Tourist Region was developed as a joint venture between the North Korean government and Hyundai.[56] In 2003, the Kaesong Industrial Region was established to allow South Korean businesses to invest in the North.[57] In the early 2000s South Korea ceased infiltrating its agents into the North.[58]

US President George W Bush, however, did not support the Sunshine Policy and in 2002 branded North Korea as a member of an Axis of Evil.[59][60]

Continuing concerns about North Korea's potential to develop nuclear missiles led in 2003 to the six-party talks that included North Korea, South Korea, the USA, Russia, China, and Japan.[61] In 2006, however, North Korea resumed testing missiles and on October 9 conducted its first nuclear test.[62]

The June 15, 2000 Joint Declaration that the two leaders signed during the first South-North summit stated that they would hold the second summit at an appropriate time. It was originally envisaged that the second summit would be held in South Korea, but that did not eventuate. South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun walked across the Korean Demilitarized Zone on October 2, 2007 and travelled on to Pyongyang for talks with Kim Jong-il.[63][64][65][66] The two sides reaffirmed the spirit of the June 15 Joint Declaration and had discussions on various issues related to realizing the advancement of South-North relations, peace on the Korean Peninsula, common prosperity of the people and the unification of Korea. On October 4, 2007, South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun and North Korean leader Kim Jong-il signed the peace declaration. The document called for international talks to replace the Armistice which ended the Korean War with a permanent peace treaty.[67]

During this period, the political developments were reflected in art. The films Shiri, in 1999, and Joint Security Area, in 2000, gave sympathetic representations of North Koreans.[68][69]

Sunshine policy ends

Lee Myung-bak government

The Sunshine Policy was formally abandoned by the new South Korean President Lee Myung-bak in 2010.[70]

On March 26, 2010, the 1,500-ton ROKS Cheonan with a crew of 104, sank off Baengnyeong Island in the Yellow Sea. Seoul said there was an explosion at the stern, and was investigating whether a torpedo attack was the cause. Out of 104 sailors, 46 died and 58 were rescued. South Korean President Lee Myung-bak convened an emergency meeting of security officials and ordered the military to focus on rescuing the sailors.[71][72] On May 20, 2010, a team of international researchers published results claiming that the sinking had been caused by a North Korean torpedo; North Korea rejected the findings.[73] South Korea agreed with the findings from the research group and President Lee Myung-bak declared afterwards that Seoul would cut all trade with North Korea as part of measures primarily aimed at striking back at North Korea diplomatically and financially.[74] North Korea denied all such allegations and responded by severing ties between the countries and announced it abrogated the previous non-aggression agreement.[75]

On November 23, 2010, North Korea's artillery fired at South Korea's Yeonpyeong island in the Yellow Sea and South Korea returned fire. Two South Korean marines and two civilians were killed, more than a dozen were wounded, including three civilians. About 10 North Koreans were believed to be killed; however the North Korean government denies this. The town was evacuated and South Korea warned of stern retaliation, with President Lee Myung-bak ordering the destruction of a nearby North Korea missile base if further provocation should occur.[76] The official North Korean news agency, KCNA, stated that North Korea only fired after the South had "recklessly fired into our sea area".[77]

In 2011 it was revealed that North Korea abducted four high-ranking South Korean military officers in 1999.[78]

Park Geun-hye government

On December 12, 2012, North Korea launched the Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2, a scientific and technological satellite, and it reached orbit.[79][80][81] In response, the United States reployed its warships in the region.[82] January–September 2013 saw an escalation of tensions between North Korea and South Korea, the United States, and Japan that began because of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2087, which condemned North Korea for the launch of Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2. The crisis was marked by extreme escalation of rhetoric by the new North Korean administration under Kim Jong-un and actions suggesting imminent nuclear attacks against South Korea, Japan, and the United States.[83]

On March 24, 2014, a crashed North Korean drone was found near Paju, the onboard cameras contained pictures of the Blue House and military installations near the DMZ. On March 31, following an exchange of artillery fire into the waters of the NLL, a North Korean drone was found crashed on Baengnyeongdo.[84][85] On September 15, wreckage of a suspected North Korean drone was found by a fisherman in the waters near Baengnyeongdo, the drone was reported to be similar to one of the North Korean drones which had crashed in March 2014.[86]

According to a 2014 BBC World Service poll, 3% of South Koreans viewed North Korea's influence positively, with 91% expressing a negative view, making South Korea, after Japan, the country with the most negative feelings of North Korea in the world.[87] However, a 2014 government-funded survey found 13% of South Koreans viewed North Korea as hostile, and 58% of South Koreans believed North Korea was a country they should cooperate with.[88]

On January 1, 2015, Kim Jong-un, in his New Year's address to the country, stated that he was willing to resume higher-level talks with the South.[89]

In the first week of August 2015, a mine went off at the DMZ, wounding two South Korean soldiers. The South Korean government accused the North of planting the mine, which the North denied. After that South Korea restarted propaganda broadcasts to the North.[90]

On August 20, 2015, North Korea fired a shell on the city of Yeoncheon. South Korea launched several artillery rounds in response. There were no casualties in the South, but some local residents evacuated.[91] The shelling caused both countries to adopt pre-war statuses and a talk that was held by high level officials in the Panmunjeom to relieve tensions on August 22, 2015, and the talks carried over to the next day.[92] Nonetheless while talks were going on, North Korea deployed over 70 percent of their submarines, which increased the tension once more on August 23, 2015.[93] Talks continued into the next day and finally concluded on August 25 when both parties reached an agreement and military tensions were eased.

Despite peace talks between South Korea and North Korea on September 9, 2016 regarding the North's missile test, North Korea continued to progress with its missile testing. North Korea carried out its fifth nuclear test as part of the state's 68th anniversary since its founding.[94] In response South Korea revealed that it had a plan to assassinate Kim Jong-un.[95]

According to a 2017 Korea Institute for National Unification, 58% of South Korean citizens had responded that unification is necessary. Among the respondents of the 2017 survey, 14% said 'we really need unification' while 44% said 'we kind of need the unification'. Regarding the survey question of 'Do we still need unification even if ROK and DPRK could peacefully coexist?', 46% agreed and 32% disagreed.[96]

Thaw in 2018

In May 2017 Moon Jae-in was elected President of South Korea with a promise to return to the Sunshine Policy.[97] In his New Year address for 2018, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un proposed sending a delegation to the upcoming Winter Olympics in South Korea.[98] The Seoul–Pyongyang hotline was reopened after almost two years.[99] At the Winter Olympics, North and South Korea marched together in the opening ceremony and fielded a united women's ice hockey team.[100] As well as the athletes, North Korea sent an unprecedented high-level delegation, headed by Kim Yo-jong, sister of Kim Jong-un, and President Kim Yong-nam, and including performers like the Samjiyon Orchestra.[101] The delegation passed on an invitation to President Moon to visit North Korea.[101] Following the Olympics, authorities of the two countries raised the possibility that they could host the 2021 Asian Winter Games together.[102] On 1 April, South Korean K-pop stars performed a concert in Pyongyang entitled "Spring is Coming", which was attended by Kim Jong-un and his wife.[103] Meanwhile, propaganda broadcasts stopped on both sides.[21]

On 27 April, a summit took place between Moon and Kim in the South Korean zone of the Joint Security Area. It was the first time since the Korean War that a North Korean leader had entered South Korean territory.[104] North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and South Korea's President Moon Jae-in met at the line that divides Korea.[105] The summit ended with both countries pledging to work towards complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.[106][107] They also vowed to declare an official end to the Korean War within a year.[108] As part of the Panmunjom Declaration which was signed by leaders of both countries, both sides also called for the end of longstanding military activities in the region of the Korean border and a reunification of Korea.[1] Also, the leaders agreed to work together to connect and modernise their railways.[109]

On 5 May, North Korea adjusted its time zone to match the South's.[110] In May, South Korea began removing propaganda loudspeakers from the border area in line with the Panmunjom Declaration.[111]

Moon and Kim met a second time on 26 May to discuss Kim's upcoming summit with Trump.[112] The summit led to further meetings between North and South Korean officials during June.[113] On June 1, officials from both countries agreed to move forward with the military and Red Cross talks.[114] They also agreed to reopen a jointly operated liaison office in Kaesong that the South had shut down in February 2016 after a North Korean nuclear test.[114] The second meeting, involving the Red Cross and military, was held at North Korea's Mount Kumgang resort on June 22 where it was agreed that family reunions would resume.[115] After the summit in April, a summit between US President Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un was held on 12 June 2018 in Singapore. South Korea hailed it as a success.

South Korea announced on 23 June 2018 that it would not conduct annual military exercises with the USA in September, and would also stop its own drills in the Yellow Sea, in order to not provoke North Korea and to continue a peaceful dialog.[116] On 1 July 2018 South and North Korea have resumed ship-to-ship radio communication, which could prevent accidental clashes between South and North Korean military vessels around the Northern Limit Line (NLL) in the West (Yellow) Sea.[117] On 17 July 2018, South and North Korea fully restored their military communication line on the western part of the peninsula.[118]

South Korea and North Korea competed as "Korea" in some events at the 2018 Asian Games.[119] The co-operation extended to the film industry, with South Korea giving their approval to screen North Korean movies at the country's local festival while inviting several moviemakers from the latter.[120][121][122] In August 2018 reunions of families divided since the Korean War took place at Mount Kumgang in North Korea.[123] In September, at a summit with Moon in Pyongyang, Kim agreed to dismantle North Korea's nuclear weapons facilities if the United States took reciprocal action. The two governments also announced that they would establish buffer zones on their borders to prevent clashes.[124] Moon became the first South Korean leader to give a speech to the North Korean public when he addressed 150,000 spectators at the Arirang Festival on 19 September.[125]

See also

- June 15th North–South Joint Declaration

- Northern Limit Line

- List of border incidents involving North Korea

- North Korea–South Korea football rivalry

- 2017–18 North Korea crisis

- North Korea–United States relations

- North Korea–Russia relations

- China–North Korea relations

- Russia–South Korea relations

- South Korea–United States relations

- China–South Korea relations

- Korean conflict

- Sunshine Policy

- Inter-Korean summit

- Inter-Korean Liaison Office

- Seoul–Pyongyang hotline

- Korean peace process

References

- 1 2 Taylor, Adam (27 April 2018). "The full text of North and South Korea's agreement, annotated". Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ↑ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Majority of South Koreans favor North Korea 'friendship' | DW | 19.02.2018". DW.COM. Archived from the original on 2018-08-01. Retrieved 2018-08-01.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 50–51, 59. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 194–95. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 68. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 66, 69. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 255–56. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 505–06. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 158.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- 1 2 Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ "Chronology of major North Korean statements on the Korean War armistice". News. Yonhap. 2009-05-28. Archived from the original on 2013-03-10.

- ↑ "North Korea ends peace pacts with South". BBC News. 2013-03-08. Archived from the original on 2013-03-10.

- ↑ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 10.

- ↑ Hunter, Helen-Louise (1999). Kim Il-song's North Korea. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. p. 189. ISBN 0-275-96296-2.

- 1 2 Tan, Yvette (25 April 2018). "North and South Korea: The petty side of diplomacy". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2004/02/15/world/south-korean-movie-unlocks-door-on-a-once-secret-past.html

- ↑ Lee Tae-hoon (7 February 2011). "S. Korea raided North with captured agents in 1967". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ↑ "Minutes of Washington Special Actions Group Meeting, Washington, August 25, 1976, 10:30 a.m." Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State. 25 August 1976. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

Clements: I like it. It doesn't have an overt character. I have been told that there have been 200 other such operations and that none of these have surfaced. Kissinger: It is different for us with the War Powers Act. I don't remember any such operations.

- 1 2 3 4 Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- 1 2 김영호. 사실로 본 한국 근현대사. 2nd ed. 서울:황금알, 2011. Print.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 12. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 19. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 35. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 36. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 83–86. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 113. ISBN 9780465031238.

- 1 2 Choe, Sang-Hun (Feb 20, 2014). "Amid Hugs and Tears, Korean Families Divided by War Reunite". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved Jan 12, 2015.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 118–19. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 142–43. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 49, 66–67. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. pp. 165–69, 173–75. ISBN 9780465031238.

- 1 2 Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 160.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 509. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 173–76. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 164.

- ↑ Blustein, Paul (13 December 1991). "Two Koreas pledge to end aggression". Washington Post. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ David E. Sanger (13 December 1991). "Koreas sign Pact renouncing force in a step to unity". New York Times. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ "Agreement on Reconciliation, Nonagression and Exchanges And Cooperation Between the South and the North". U.S. Department of State. 13 December 1991. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 68, 76. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 165, 180. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 161.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 179. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 179–80. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 107–08. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ https://news.joins.com/article/12709883

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 504. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 124–25. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 132–33. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Korean leaders in historic talks Archived 2007-10-16 at the Wayback Machine., BBC, Tuesday, 2 October 2007, 10:14 GMT

- ↑ In pictures: Historic crossing Archived 2008-03-07 at the Wayback Machine., BBC, 2 October 2007, 10:15 GMT

- ↑ Mixed feelings over Koreas summit Archived 2007-11-15 at the Wayback Machine., BBC, 2 October 2007, 10:17 GMT

- ↑ Kim greets Roh in Pyongyang before historic summit Archived 2007-11-09 at the Wayback Machine., CNN. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ↑ Korean leaders issue peace call Archived 2007-10-21 at the Wayback Machine., BBC, 4 October 2007.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 184–85. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 163.

- ↑ South Korea Formally Declares End to Sunshine Policy Archived 2012-04-12 at the Wayback Machine., Voice of America Archived 2012-05-14 at the Wayback Machine., 18 November 2010

- ↑ "Geopolitical Weekly". Archived from the original on 2015-06-10.

- ↑ "'Blast' sinks S Korea navy ship". BBC News. March 26, 2010. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Anger at North Korea over sinking". BBC News. 2010-05-20. Archived from the original on 2010-05-23. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ Clinton: Koreas security situation 'precarious' Archived 2010-05-25 at the Wayback Machine., by Matthew Lee, Associated Press, 24-05-2010

- ↑ Text from North Korea statement Archived 2010-06-05 at the Wayback Machine., by Jonathan Thatcher, Reuters, 25-05-2010

- ↑ "(LEAD) S. Korea vows 'stern retaliation' against N. Korea's attacks" (in Korean). English.yonhapnews.co.kr. 2010-11-23. Archived from the original on 2012-06-17. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ McDonald, Mark (November 23, 2010). "North and South Korea Exchange Fire, Killing Two". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- ↑ Kim, Rahn (2011-05-20). "North Korea abducted 4 South Korean military officers'". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

- ↑ "KCST Spokesman on Launching Time of Satellite". Kcna.co.jp. 2012-12-08. Archived from the original on 2014-10-12. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ "DPRK Succeeds in Satellite Launch". Kcna.co.jp. 2012-12-12. Archived from the original on 2013-01-02. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ "KCNA Releases Report on Satellite Launch". Kcna.co.jp. 2012-12-12. Archived from the original on 2013-01-02. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ "US moves warships to track North Korea rocket launch". Bbc.co.uk. 2012-12-07. Archived from the original on 2013-03-19. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ "In Focus North Korea's Nuclear Threats". Archived from the original on 2013-04-16.

- ↑ "Mystery drones found in Baengnyeong, Paju". JoongAng Daily. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 16 September 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "South Korea: Drones 'confirmed as North Korean'". BBC News. 8 May 2014. Archived from the original on 16 September 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "South Korea finds wreckage in sea of suspected North Korean drone". Reuters. 15 September 2014. Archived from the original on 16 September 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ 2014 World Service Poll Archived 2015-03-05 at the Wayback Machine. BBC

- ↑ Zachary Keck (30 May 2014). "South Koreans View North Korea as Cooperative Partner". The Diplomat. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ "Yahoo! News". Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ↑ "Land Mine Blast South Korea Threatens North with Retaliation". Archived from the original on 2015-08-13.

- ↑ "South Korea evacuation after shelling on western border". 20 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015 – via www.bbc.com.

- ↑ "Rival Koreas Restart Talks, Pull Back from Brink for Now". Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ↑ "North Korea Deploys Submarines while Talks with Seoul Resume". Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ↑ Kim, Jack (10 September 2016). "South Korea says North's nuclear capability 'speeding up', calls for action". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Hancocks, Paula (23 September 2016). "South Korea reveals it has a plan to assassinate Kim Jong Un". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ "통일연구원" (in Korean). Kinu.or.kr. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ↑ "South Korea's likely next president warns the U.S. not to meddle in its democracy". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2017-05-02. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- ↑ Kim Jong Un offers rare olive branch to South Korea Archived 2018-01-01 at the Wayback Machine. CNN. By Alanne Orjoux and Steve George. January 2, 2018. Downloaded January 2, 2018.

- ↑ Kim, Hyung-Jin (3 January 2018). "North Korea reopens cross-border communication channel with South Korea". Chicago Tribune. AP. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ↑ Gregory, Sean; Gangneug (10 February 2018). "'Cheer Up!' North Korean Cheerleaders Rally Unified Women's Hockey Team During 8-0 Loss". Time. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- 1 2 Ji, Dagyum (12 February 2018). "Delegation visit shows N. Korea can take "drastic" steps to improve relations: MOU". NK News. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "North Korea could co-host 2021 Asian Games with South, official says". The Guardian. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ Kim, Christine; Yang, Heekyong (2 April 2018). "North Korea's Kim Jong Un, wife, watch South Korean K-pop stars perform in Pyongyang". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Location of planned inter-Korean summit hints at changes in North Korea strategy, say experts". The Straits Times. 8 March 2018. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ "North Korea-South Korea summit: Live updates". CNN. 2018-06-05. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ↑ Sang-Hun, Choe (2018-04-27). "North and South Korea Set Bold Goals: A Final Peace and No Nuclear Arms". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ↑ Kim, Christine. "Korean leaders aim for end of war, 'complete denuclearisation'..." U.S. Archived from the original on 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ↑ "North and South Korea Set Bold Goals: A Final Peace and No Nuclear Arms - The New York Times". Nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ↑ "North Korea and South Korea make pledge to connect border railways - Global Rail News". 27 April 2018. Archived from the original on 8 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ "PressTV-North Korea unifies time zone with South". Presstv.com. 2018-05-05. Archived from the original on 2018-06-10. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ↑ South Korea begins dismantling propaganda speakers - CNN Video, archived from the original on 2018-05-16, retrieved 2018-05-16

- ↑ "North and South Korean leaders meet to discuss Kim-Trump summit". Channel NewsAsia. 2018-05-26. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ↑ https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/full-address-by-south-korean-president-moon-jae-in-on-may-26-inter-korea-summit

- 1 2 https://www.cnbc.com/2018/06/01/rival-koreas-agree-to-military-red-cross-talks-for-peace.html

- ↑ https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/diplomacy/article/2152091/north-and-south-korea-confirm-family-reunions-will-resume-august

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-06-28. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ↑

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-07-17. Retrieved 2018-07-17.

- ↑ "North & South Korea agree to some combined teams at Asian Games". BBC Sport. 18 June 2018. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ↑ "South Korea approves rare screening of North Korea movies at film festival". The Straits Times. 10 July 2018. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ↑ "North, South Korea agree to joint sports events and create combined teams for Asian Games". Channel NewsAsia. Archived from the original on 2018-07-10. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ↑ "South Korean film industry forges closer ties with North Korea". Screen. Archived from the original on 2018-07-10. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ↑ Ji, Dagyum (24 August 2018). "Second group of separated Korean families meet for three day reunion". NK News.

- ↑ "North Korea agrees to dismantle nuclear complex if United States takes reciprocal action, South says". ABC. 19 September 2019.

- ↑ "South Korea's Moon Jae-in makes unprecedented mass games speech". BBC. 20 September 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Relations of North Korea and South Korea. |

- Inter-Korean Relations: Past, Present and Future (Introduction) – cfr.org

- Inter-Korean Relations: Past, Present and Future (Panel 1) – cfr.org

- ROK and Inter-Korean relations

- Eating the Oxen of the Sun – The Odyssey of Unification

- Inter-Korean tensions: ideology first, at any cost? by Alain Nass (expert on Asia and Korea), Asia & Pacific Network, October 2011

- Research Council on Unification Policy

- Korea institute of national unification

- Brookings Institution

- New York Times on North Korea

.svg.png)