Demographics of Puerto Rico

| Demographics of Puerto Rico | |

|---|---|

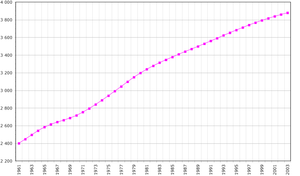

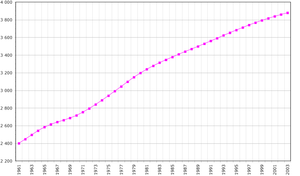

Population Change Timeline (1961–2003) | |

.jpg) Population Density | |

| Population (2017) | 3,337,177 |

| Male population (2010) | 1,785,171 |

| Female population (2010) | 1,940,618 |

| Population growth | -1.32% |

| Birth rate | 8.3/1,000 |

| Death rate | 8.7/1,000 |

| Infant mortality rate | 8.24/1,000 |

| Life expectancy | 78.29 years |

| Nationality | American |

| Demographic bureaus | 2010 United States Census |

The population of Puerto Rico has been shaped by Amerindian settlement, European colonization especially under the Spanish Empire, slavery and economic migration. This article is about the demographic features of the population of Puerto Rico, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

History of migration

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1765 | 44,883 | — |

| 1775 | 70,250 | +56.5% |

| 1800 | 155,426 | +121.2% |

| 1815 | 220,892 | +42.1% |

| 1832 | 350,051 | +58.5% |

| 1846 | 447,914 | +28.0% |

| 1860 | 583,308 | +30.2% |

| 1877 | 731,648 | +25.4% |

| 1887 | 798,565 | +9.1% |

| 1899 | 953,243 | +19.4% |

| 1910 | 1,118,012 | +17.3% |

| 1920 | 1,299,809 | +16.3% |

| 1930 | 1,543,913 | +18.8% |

| 1940 | 1,869,255 | +21.1% |

| 1950 | 2,210,703 | +18.3% |

| 1960 | 2,349,544 | +6.3% |

| 1970 | 2,712,033 | +15.4% |

| 1980 | 3,196,520 | +17.9% |

| 1990 | 3,522,037 | +10.2% |

| 2000 | 3,808,610 | +8.1% |

| 2010 | 3,725,789 | −2.2% |

| 2017 | 3,337,177 | −10.4% |

| ||

Sometime between 400 B.C. and A.D. 100, the Arawak group of Amerindians inhabited Puerto Rico. Around A.D. 600, the Arawaks no longer lived on the island, perhaps because they had integrated with another culture or perhaps because they had been killed by illness.[4] By A.D. 1000, the indigenous Taíno inhabited the island. They called the island Borikén (alternatively, Borinquén), which means "land of the valiant one" [5][4] and later Puerto Ricans called themselves boricua, borincano and borinqueño to embrace their indigenous identity.[6] In the 15th century, the Carib lived on nearby islands and periodically invaded Taíno villages.[4]

Immigration

The Spanish conquered the island, assuming government in 1508, colonized it, and assumed hegemony over the natives. The Taíno population dwindled due to disease, tribal warfare, and forced labor, so the Spanish began importing large numbers of slaves from Africa. Spanish men arrived on the island disproportionately to Spanish women; African and Taíno women would sometimes marry them, resulting in a mixed tri-racial ethnicity.

In the late 18th century, the number of African slaves began to dwindle on the island. The British ban on slavery resulted in slave raids on Puerto Rico. Many slaves also escaped to neighboring islands.

During the 19th century large numbers of immigrants from Spain, as well as numerous Spaniards living in former Spanish colonies in South America, also arrived in Puerto Rico (See Spanish immigration to Puerto Rico). Although the vast majority of settlers came from Spain, Catholics from France, Ireland, Italy and other European countries were also granted land by Spain as one of the provisions of the Real Cédula de Gracias de 1815 (Royal Decree of Graces of 1815). These immigrants were allowed to settle on the island, with a certain amount of free land and enslaved persons granted to them. In return, they had to profess fealty to the Spanish Crown. During the early 20th century Jews began to settle in Puerto Rico. The first large group of Jews to settle in Puerto Rico were European refugees fleeing German–occupied Europe in the 1930s. Puerto Rico's economic boom of the 1950s attracted a considerable number of Jewish families from the U.S. mainland, who were joined after 1959 by an influx of Jewish emigres from Castro's Cuba.[7]

The mass immigration that occurred during the 19th century helped the population grow from 155,000 in 1800 to almost 1,000,000 at the close of the century.

Emigration

Emigration has been a major part of Puerto Rico's recent history as well. Starting in the post-World War II period waves of Puerto Ricans moved to the continental United States, particularly to New York City; Newark, Jersey City, Paterson, and Camden, New Jersey; Providence, Rhode Island; Springfield; Hartford and New Haven, Connecticut; Boston, Massachusetts; Orlando, Miami and Tampa, Florida; Philadelphia and Reading, Pennsylvania; Washington, D.C., Chicago and Los Angeles, California. This continued even as Puerto Rico's economy improved and its birth rate declined.

Vital statistics

| Average population (x 1000) | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | TFR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 1 118 | 37 600 | 26 600 | 11 000 | 33.6 | 23.8 | 9.8 | |

| 1911 | 1 140 | 39 100 | 26 600 | 12 500 | 34.3 | 23.3 | 11.0 | |

| 1912 | 1 150 | 40 400 | 26 900 | 13 500 | 35.1 | 23.4 | 11.7 | |

| 1913 | 1 170 | 42 700 | 23 200 | 19 500 | 36.5 | 19.8 | 16.7 | |

| 1914 | 1 190 | 47 400 | 22 300 | 25 100 | 39.8 | 18.7 | 21.1 | |

| 1915 | 1 210 | 45 000 | 25 000 | 20 000 | 37.2 | 20.7 | 16.5 | |

| 1916 | 1 230 | 43 200 | 29 400 | 13 800 | 35.1 | 23.9 | 11.2 | |

| 1917 | 1 250 | 44 300 | 38 600 | 5 700 | 35.4 | 30.9 | 4.5 | |

| 1918 | 1 260 | 51 500 | 38 900 | 12 600 | 40.9 | 30.9 | 10.0 | |

| 1919 | 1 280 | 46 000 | 30 300 | 15 700 | 35.9 | 23.7 | 12.2 | |

| 1920 | 1 300 | 49 900 | 29 600 | 20 300 | 38.4 | 22.8 | 15.6 | |

| 1921 | 1 320 | 50 600 | 29 700 | 20 900 | 38.3 | 22.5 | 15.8 | |

| 1922 | 1 350 | 50 500 | 29 400 | 21 100 | 37.4 | 21.8 | 15.6 | |

| 1923 | 1 370 | 50 700 | 26 900 | 23 800 | 37.0 | 19.6 | 17.4 | |

| 1924 | 1 400 | 53 600 | 27 200 | 26 400 | 38.3 | 19.4 | 18.9 | |

| 1925 | 1 420 | 52 700 | 33 200 | 19 500 | 37.1 | 23.4 | 13.7 | |

| 1926 | 1 450 | 55 500 | 32 300 | 23 200 | 38.3 | 22.3 | 16.0 | |

| 1927 | 1 470 | 58 200 | 33 500 | 24 700 | 39.6 | 22.8 | 16.8 | |

| 1928 | 1 500 | 52 900 | 29 700 | 23 200 | 35.3 | 19.8 | 15.5 | |

| 1929 | 1 520 | 52 300 | 40 700 | 11 600 | 34.4 | 26.8 | 7.6 | |

| 1930 | 1 544 | 54 300 | 31 500 | 22 800 | 35.2 | 20.4 | 14.8 | |

| 1931 | 1 580 | 71 600 | 35 200 | 36 400 | 45.3 | 22.3 | 23.0 | |

| 1932 | 1 615 | 66 400 | 35 500 | 30 900 | 41.1 | 22.0 | 19.1 | |

| 1933 | 1 647 | 61 600 | 36 700 | 24 900 | 37.4 | 22.3 | 15.1 | |

| 1934 | 1 679 | 65 595 | 31 684 | 33 911 | 39.1 | 18.9 | 20.2 | |

| 1935 | 1 710 | 67 585 | 30 748 | 36 837 | 39.5 | 18.0 | 21.5 | |

| 1936 | 1 743 | 68 962 | 34 790 | 34 172 | 39.6 | 20.0 | 19.6 | |

| 1937 | 1 777 | 67 919 | 37 132 | 30 787 | 38.2 | 20.9 | 17.3 | |

| 1938 | 1 810 | 69 823 | 33 870 | 35 953 | 38.6 | 18.7 | 19.9 | |

| 1939 | 1 844 | 73 044 | 32 631 | 40 413 | 39.6 | 17.7 | 21.9 | |

| 1940 | 1 879 | 72 388 | 34 477 | 37 911 | 38.5 | 18.3 | 20.2 | |

| 1941 | 1 926 | 76 130 | 35 551 | 40 579 | 39.5 | 18.5 | 21.1 | |

| 1942 | 1 973 | 78 405 | 32 218 | 46 187 | 39.7 | 16.3 | 23.4 | |

| 1943 | 2 012 | 77 304 | 29 065 | 48 239 | 38.4 | 14.4 | 24.0 | |

| 1944 | 2 037 | 82 534 | 29 843 | 52 691 | 40.5 | 14.7 | 25.9 | |

| 1945 | 2 070 | 86 680 | 28 837 | 57 843 | 41.9 | 13.9 | 27.9 | |

| 1946 | 2 100 | 88 421 | 27 517 | 60 904 | 42.1 | 13.1 | 29.0 | |

| 1947 | 2 149 | 91 305 | 25 407 | 65 898 | 42.5 | 11.8 | 30.7 | |

| 1948 | 2 187 | 87 809 | 26 209 | 61 600 | 40.2 | 12.0 | 28.2 | |

| 1949 | 2 197 | 85 625 | 23 389 | 62 236 | 39.0 | 10.6 | 28.3 | |

| 1950 | 2 218 | 86 038 | 21 895 | 64 143 | 38.8 | 9.9 | 27.9 | |

| 1951 | 2 210 | 84 076 | 22 374 | 61 702 | 38.0 | 10.1 | 27.9 | |

| 1952 | 2 212 | 80 438 | 20 480 | 59 958 | 36.3 | 9.3 | 27.1 | |

| 1953 | 2 221 | 77 754 | 17 972 | 59 782 | 35.0 | 8.1 | 26.9 | |

| 1954 | 2 233 | 78 008 | 16 783 | 61 225 | 34.9 | 7.5 | 27.4 | |

| 1955 | 2 247 | 79 221 | 16 243 | 62 978 | 35.2 | 7.2 | 28.0 | |

| 1956 | 2 262 | 78 177 | 16 607 | 61 570 | 34.5 | 7.3 | 27.2 | |

| 1957 | 2 279 | 76 068 | 16 022 | 60 046 | 33.3 | 7.0 | 26.3 | |

| 1958 | 2 299 | 76 128 | 16 099 | 60 029 | 33.1 | 7.0 | 26.1 | |

| 1959 | 2 323 | 74 933 | 15 870 | 59 063 | 32.2 | 6.8 | 25.4 | |

| 1960 | 2 356 | 76 015 | 15 841 | 60 174 | 32.2 | 6.7 | 25.5 | |

| 1961 | 2 396 | 75 563 | 16 361 | 59 202 | 31.5 | 6.8 | 24.7 | |

| 1962 | 2 442 | 76 677 | 16 575 | 60 102 | 31.3 | 6.8 | 24.6 | |

| 1963 | 2 491 | 77 382 | 17 386 | 59 996 | 31.0 | 7.0 | 24.0 | |

| 1964 | 2 538 | 78 837 | 18 556 | 60 281 | 31.0 | 7.3 | 23.7 | |

| 1965 | 2 578 | 79 586 | 17 719 | 61 867 | 30.8 | 6.9 | 24.0 | |

| 1966 | 2 609 | 75 735 | 17 506 | 58 229 | 29.0 | 6.7 | 22.3 | |

| 1967 | 2 634 | 70 755 | 16 780 | 53 975 | 26.8 | 6.4 | 20.4 | |

| 1968 | 2 656 | 67 989 | 17 481 | 50 508 | 25.5 | 6.6 | 19.0 | |

| 1969 | 2 680 | 67 577 | 17 669 | 49 908 | 25.1 | 6.6 | 18.6 | |

| 1970 | 2 710 | 67 438 | 18 080 | 49 358 | 24.8 | 6.7 | 18.2 | 2.69 |

| 1971 | 2 746 | 71 114 | 18 144 | 52 970 | 25.8 | 6.6 | 19.2 | 2.82 |

| 1972 | 2 787 | 68 914 | 19 011 | 49 903 | 24.7 | 6.8 | 17.9 | 2.67 |

| 1973 | 2 833 | 68 821 | 19 257 | 49 564 | 24.2 | 6.8 | 17.5 | 2.67 |

| 1974 | 2 882 | 70 082 | 19 490 | 50 592 | 24.3 | 6.7 | 17.5 | 2.65 |

| 1975 | 2 932 | 69 691 | 19 073 | 50 618 | 23.7 | 6.5 | 17.2 | 2.61 |

| 1976 | 2 984 | 72 883 | 19 893 | 52 990 | 24.4 | 6.7 | 17.7 | 2.77 |

| 1977 | 3 037 | 75 151 | 19 895 | 55 256 | 24.7 | 6.5 | 18.2 | 2.93 |

| 1978 | 3 090 | 75 066 | 19 876 | 55 190 | 24.2 | 6.4 | 17.8 | 2.86 |

| 1979 | 3 141 | 73 781 | 20 390 | 53 391 | 23.4 | 6.5 | 17.0 | 2.77 |

| 1980 | 3 188 | 73 060 | 20 486 | 52 574 | 22.9 | 6.4 | 16.4 | 2.75 |

| 1981 | 3 230 | 71 365 | 21 197 | 50 168 | 22.0 | 6.5 | 15.5 | 2.64 |

| 1982 | 3 269 | 69 336 | 21 522 | 47 814 | 21.2 | 6.6 | 14.6 | 2.57 |

| 1983 | 3 305 | 65 742 | 21 499 | 44 243 | 19.8 | 6.5 | 13.4 | 2.44 |

| 1984 | 3 338 | 63 321 | 21 733 | 41 588 | 18.9 | 6.5 | 12.4 | 2.37 |

| 1985 | 3 370 | 63 629 | 23 194 | 40 435 | 18.8 | 6.9 | 12.0 | 2.34 |

| 1986 | 3 400 | 63 551 | 23 387 | 40 164 | 18.6 | 6.9 | 11.8 | 2.31 |

| 1987 | 3 429 | 64 393 | 23 954 | 40 439 | 18.7 | 7.0 | 11.8 | 2.27 |

| 1988 | 3 457 | 64 081 | 25 123 | 38 958 | 18.5 | 7.2 | 11.2 | 2.27 |

| 1989 | 3 487 | 66 692 | 25 987 | 40 705 | 19.1 | 7.4 | 11.6 | 2.36 |

| 1990 | 3 518 | 66 565 | 26 138 | 40 407 | 18.9 | 7.4 | 11.5 | 2.35 |

| 1991 | 3 552 | 64 498 | 26 321 | 38 177 | 18.2 | 7.4 | 10.7 | 2.20 |

| 1992 | 3 587 | 64 471 | 27 389 | 37 082 | 18.0 | 7.6 | 10.3 | 2.18 |

| 1993 | 3 623 | 65 258 | 28 493 | 36 765 | 18.0 | 7.9 | 10.1 | 2.14 |

| 1994 | 3 657 | 64 341 | 28 428 | 35 913 | 17.6 | 7.8 | 9.8 | 2.08 |

| 1995 | 3 690 | 63 502 | 30 184 | 33 318 | 17.2 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 2.08 |

| 1996 | 3 719 | 63 259 | 29 871 | 33 388 | 17.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 2.06 |

| 1997 | 3 747 | 64 214 | 29 119 | 35 095 | 17.1 | 7.8 | 9.4 | 2.13 |

| 1998 | 3 770 | 60 518 | 29 990 | 30 528 | 16.1 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 1.98 |

| 1999 | 3 787 | 59 684 | 29 145 | 30 539 | 15.8 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 1.94 |

| 2000 | 3 797 | 59 460 | 28 550 | 30 910 | 15.7 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 1.93 |

| 2001 | 3 799 | 55 982 | 28 794 | 27 188 | 14.7 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 1.85 |

| 2002 | 3 795 | 52 871 | 28 098 | 24 773 | 13.9 | 7.4 | 6.5 | 1.77 |

| 2003 | 3 785 | 50 803 | 28 356 | 22 447 | 13.4 | 7.5 | 5.9 | 1.71 |

| 2004 | 3 773 | 51 239 | 29 066 | 22 173 | 13.6 | 7.7 | 5.9 | 1.74 |

| 2005 | 3 761 | 50 687 | 29 702 | 20 985 | 13.5 | 7.9 | 5.6 | 1.73 |

| 2006 | 3 750 | 48 597 | 28 206 | 20 391 | 13.0 | 7.5 | 5.4 | 1.67 |

| 2007 | 3 739 | 46 642 | 29 169 | 17 473 | 12.5 | 7.8 | 4.7 | 1.64 |

| 2008 | 3 729 | 45 620 | 29 050 | 16 570 | 11.5 | 7.8 | 3.7 | 1.62 |

| 2009 | 3 719 | 44 773 | 29 005 | 15 768 | 11.3 | 7.8 | 3.5 | 1.59 |

| 2010 | 3 722 | 42 153 | 29 153 | 13 000 | 11.3 | 7.8 | 3.5 | 1.62 |

| 2011 | 3 679 | 41 080 | 29 742 | 11 338 | 11.2 | 8.1 | 3.1 | 1.60 |

| 2012 | 3 634 | 38 900 | 29 448 | 9 228 | 10.7 | 8.1 | 2.5 | 1.54 |

| 2013 | 3 593 | 38 986 | 29 009 | 9 977 | 10.9 | 8.1 | 2.8 | 1.47 |

| 2014 | 3 535 | 34 485 | 30 224 | 4 261 | 9.8 | 8.5 | 1.2 | 1.43 |

| 2015 | 3 474 | 31 157 | 28 279 | 2 878 | 9.0 | 8.1 | 0.9 | 1.34 |

| 2016 | 3 411 | 28 326 | 29 613 | -1 287 | 8.3 | 8.7 | -0.4 | 1.24[12] |

| 2017 | 3 337 | 24 370 | 30 977 | −6 607 | 7.3 | 9.3 | −2.0 | |

Current vital statistics

Births

- from January-March 2017 =

- from January-March 2018 =

Deaths

- from January-March 2017 =

- from January-March 2018 =

Natural growth

- from January-March 2017 =

- from January-March 2018 =

Structure of the population

[14] Structure of the population (01.07.2012) (Estimates) (Data refer to projections based on the 2010 Population Census) :

| Age Group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1 755 479 | 1 911 605 | 3 667 084 | 100 |

| 0–4 | 107 000 | 102 597 | 209 597 | 5.72 |

| 5–9 | 116 188 | 109 665 | 225 853 | 6.16 |

| 10–14 | 129 722 | 123 006 | 252 728 | 6.89 |

| 15–19 | 138 646 | 132 250 | 270 896 | 7.39 |

| 20–24 | 134 894 | 131 768 | 266 662 | 7.27 |

| 25–29 | 112 981 | 117 257 | 230 238 | 6.28 |

| 30–34 | 115 030 | 125 281 | 240 311 | 6.55 |

| 35–39 | 111 971 | 121 837 | 233 808 | 6.38 |

| 40–44 | 113 223 | 123 276 | 236 499 | 6.45 |

| 45–49 | 114 114 | 129 441 | 243 555 | 6.64 |

| 50–54 | 109 550 | 127 211 | 236 761 | 6.46 |

| 55–59 | 103 031 | 123 108 | 226 139 | 6.17 |

| 60–64 | 96 256 | 115 745 | 212 001 | 5.78 |

| 65–69 | 86 858 | 104 308 | 191 166 | 5.21 |

| 70–74 | 64 745 | 79 593 | 144 338 | 3.94 |

| 75–79 | 46 652 | 60 431 | 107 083 | 2.92 |

| 80–84 | 29 398 | 41 911 | 71 309 | 1.94 |

| 85+ | 25 220 | 42 290 | 68 140 | 1.86 |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–14 | 352 910 | 335 268 | 688 178 | 18.77 |

| 15–64 | 1 149 696 | 1 247 174 | 2 396 870 | 65.36 |

| 65+ | 252 873 | 329 163 | 582 036 | 15.87 |

Life expectancy

| Period | Life expectancy in

Years |

Period | Life expectancy in

Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–1955 | 63.5 | 1985–1990 | 74.6 |

| 1955–1960 | 67.9 | 1990–1995 | 73.8 |

| 1960–1965 | 69.1 | 1995–2000 | 74.9 |

| 1965–1970 | 70.7 | 2000–2005 | 76.8 |

| 1970–1975 | 72.4 | 2005–2010 | 77.8 |

| 1975–1980 | 73.5 | 2010–2015 | 79.2 |

| 1980–1985 | 73.9 |

Source: UN World Population Prospects[15]

Race and ethnic group

| Racial groups – Puerto Rico[16][17][18][19][20] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | White % | Non-White % |

| 1802 | 42.0 | 58.0 |

| 1812 | 40.8 | 59.2 |

| 1820 | 39.4 | 60.6 |

| 1830 | 45.1 | 54.9 |

| 1877 | 52.3 | 47.7 |

| 1887 | 53.5 | 46.5 |

| 1897 | 64.3 | 35.7 |

| 1899 | 61.8 | 38.2 |

| 1910 | 64.5 | 35.5 |

| 1920 | 72.0 | 28.0 |

| 1930 | 73.3 | 26.7 |

| 1935 | 75.2 | 24.8 |

| 1940 | 76.0 | 24.0 |

| 1950 | 79.7 | 20.3 |

| 2000 | 80.5 | 19.5 |

| 2010 | 75.8 | 24.2 |

| Racial composition of the Puerto Rican population, by the census, 1802–2010. | ||

Race and origin history

The first census by the United States in 1899 reported a population of 953,243 inhabitants, 61.8% of them classified as white, 31.9% as mixed, and 6.3% as black.

A strong European immigration wave and large importation of slaves from Africa helped increase the population of Puerto Rico sixfold during the 19th century. No major immigration wave occurred during the 20th century.[21]

The federal Naturalization Act, signed into law on March 26, 1790, by President Washington stated that immigrants to the United States had to be White according to the definition under the British Common Law, which the United States inherited. The legal definition of Whiteness differed greatly from White Society's informal definition, thus Jews, Gypsies, Middle Eastern Peoples and those of the Indian Subcontinent were before 1917 classified as White for Immigration purposes but not considered White by the society at large. The Naturalization Act of 1870, passed during Reconstruction, allowed for peoples of African descent to become U.S. Citizens but it excluded other nonwhites. The U.S. Supreme Court in the case United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898) declared that all nonwhites who were born in the United States were eligible for citizenship via the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment. U.S. Immigration Policy was first restricted toward Chinese with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Gentleman's Agreement of 1907 in which Japan voluntarily barred emigration to the United States and the Immigration Act of 1917 or the Asiatic Barred Zone which barred immigrants from all of the Middle East, the Steppes and the Orient, excluding the Philippines which was then a US Colony. European Jews and Gypsies, although of Asiatic Ancestry, were not affected by the Asiatic Barred Zone, as they held European Citizenship. The Johnson-Reed act of 1924 applied only to the Eastern Hemisphere. The Act imposed immigration quotas on Europe, which allowed for easy immigration from Northern and Western Europe, but almost excluded the Mediterranean and Slavic Nations. Africa and Asia were excluded altogether. The Western Hemisphere remained unrestricted to immigrate to the United States. Thus under the Immigration Act of 1924 all Hispanics and Caribbeans could immigrate to the United States, but a White family from Poland or Russia could not immigrate. Puerto Rican Citizenship was created under the Foraker Act, Pub.L. 56–191, 31 Stat. 77 but it wasn't until 1917 that Puerto Ricans were granted full American Citizenship under the Jones–Shafroth Act (Pub.L. 64–368, 39 Stat. 951. Puerto Ricans, excluding those of obvious African ancestry, were like most Hispanics formally classified as White under U.S. Law, but this classification did not prevent informal discrimination against them by Anglo-Americans.

Until 1950 the U.S. Bureau of the Census attempted to quantify the racial composition of the island's population, while experimenting with various racial taxonomies. In 1960 the census dropped the racial identification question for Puerto Rico but included it again in the year 2000. The only category that remained constant over time was white, even as other racial labels shifted greatly—from "colored" to "Black", "mulatto" and "other". Regardless of the precise terminology, the census reported that the bulk of the Puerto Rican population was white from 1899 to 2000.[17]

In the late 1700s, Puerto Rico had laws like the Regla del Sacar or Gracias al Sacar where a person of mixed ancestry could be considered legally white so long as they could prove that at least one person per generation in the last four generations had also been legally white. Therefore, people of mixed ancestry with known white lineage were classified as white, the opposite of the "one-drop rule" in the United States.[22]

According to the 1920 Puerto Rico census, 2,505 individuals immigrated to Puerto Rico between 1910 and 1920. Of these, 2,270 were classified as "white" in the 1920 census (1,205 from Spain, 280 from Venezuela, 180 from Cuba, and 135 from the Dominican Republic). During the same 10-year period, 7,873 Puerto Ricans emigrated to the U.S. Of these, 6,561 were listed as "white" on the U.S mainland census, 909 as "Spanish white" and 403 as "black".[23]

According to the 2015 Race and Hispanic Origin estimate (2011–2015 American Community Survey) published by the US Census Bureau, the data for Puerto Rico was as follows:[24]

- White alone 2,495,997

- Black or African American alone 301,519

- American Indian and Alaska Native alone 11,775

- Asian alone 10,159

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone 129

- Some Other Race alone 431,443

- Two or More Races 332,051

- Hispanic or Latino (of any race) 3,547,288

- White alone, Not Hispanic or Latino 24,900

Genetic studies

| Racial distribution – 2000 Census[25] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race | Population | % of Total |

| Total | 3,808,610 | 100% |

| One race | 3,650,195 | 95.8% |

| :White | 3,064,862 | 80.5% |

| :Black/African American | 302,933 | 8.0% |

| :American Indian and Alaska Native | 13,336 | 0.4% |

| :Asian | 7,960 | 0.2% |

| :Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1,093 | 0.0% |

| :Some other race | 260,011 | 6.8% |

| Two or more races | 158,415 | 4.2% |

| Island Identity survey – 2000 census[26] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Island Identity | % of Total | |

| Puerto Rican | 69% | |

| American | 2.5% | |

| Spaniard | 2.1% | |

| Dominican | 1.7% | |

| Hispanic | 0.8% | |

| Racial distribution – 2006 ACS[27] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race | Population | % of Total |

| White | 2,986,427 | 75.8% |

| Black/African American | 286,049 | 7.3% |

| American Indian & Alaska Native | 7,831 | 0.2% |

| Asian | 12,646 | 0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 145 | 0.0% |

| Some other race | 430,358 | 10.9% |

| Two or more races | 217,170 | 5.5% |

Puerto Ricans, on average, have genetic contributions from Europeans, West Africans, and Native Americans of approximately 66%, 18%, and 16%, respectively.[28] A recent study of Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from 800 individuals found that patrilineal input, as indicated by the Y-chromosome, showed 66% of Puerto Ricans could trace their ancestry to male European ancestors, 18% could trace it to male African ancestors, and 16% could trace it to male Native American ancestors.[29]

Women in the diaspora

In a study done on Puerto Rican women (of all races) born on the island but living in New York by Carolina Bonilla, Mark D. Shriver and Esteban Parra in 2004, the ancestry proportions corresponding to the three parental populations were found to be 53.3±2.8% European, 29.1±2.3% West African, and 17.6±2.4% Native American based on autosomal ancestry informative markers. Although autosomal markers tests seem to draw a more broad picture than that of single, gender-based mtDNA and Y-Chromosome tests, the problem with autosomnal DNA is in the archaic categories used: "European", "Sub-Saharan African", "East Asian" & "Native American". "Asian" (South, North or East) & "North African" are not included. These generalised categories may not take into account the complexity of migratory patterns across the Old World. The study also found that, from the women sampled, 98% had European ancestry markers, 87% had African ancestry markers, 84% had Native American ancestry markers, 5% showed only African and European markers, 4% showed mostly Native American and European markers, 2% showed only African markers, and 2% showed mostly European markers.[30]

The Psychology of Women and Childbirth issues

Extensive research proves that childbirth causes a multitude of physical and psychological impacts on women. Women who become pregnant can experience symptoms such as anxiety, paranoia, depression, anxiousness and moodiness. Extensive epidemiological research on the mental health of Puerto Rican women has proven that the majority of women experiences illnesses that they refer to as “nervios” and “ataques de nervios” or “Nerves” and “attack of nerves”. Due to impoverished communities in Puerto Rico, poor healthcare access and reliance; women have shown to display more pronounced mental illnesses, with little to no outlet. As a result of the debt crisis in Puerto Rico, insurance companies purposely delayed the issuing of paychecks to doctors. Additionally, insurance companies also overruled the doctors’ medical decisions and replaced it for a less costly alternative. In 2016, physicians in Puerto Rico earned a median of $41.45 per hour which is less than half of the median that was earned by physicians in the United States which was $99.48 per hour. Due to better opportunities within the United States, many healthcare professionals have fled the island. Between 2005 and 2013, 1,200 physicians and surgeons left to the United States which equated 12% of the total medics who worked in the island at that time. Mental illness amongst childbearing women also became more pronounced after Hurricane Maria. Hurricane Maria impacted resource and health care availability; Moreover, after the migration of Puerto Rican professionals as a result of the extensive damage left by Hurricane Maria; women were left with limited medical resources. [31] [32] [33] These findings are consistent with the historical record that the native male Taino population was virtually wiped out shortly after the arrival of the Spanish colonists to the Island.[34]

Pre Pregnancy

Women who intend to become pregnant in Puerto Rico report fearing that having children will be a mistake since they feel they will not be able to properly financially support their children. In April of 2016, the CDC reported that 65% of pregnancies in Puerto Rico were unintended. Accessibility to all forms of contraceptives are limited by high out of pocket costs, inadequate reimbursements made by insurance companies, lack of effective resource distribution, limited number of family planning and delivery sites, as well as a lack of education on various contraception options. The island also has a shortage of properly trained medical personnel with the ability to insert, remove, and manage long-term reversible contraceptives (such as nexplanon, implanon, iud, copper iud, and depo vera shots). All of these hindrances that inhibit women to have access to contraception relate back to the poverty faced by many in Puerto Rico.[35]

During Pregnancy

Complications of pregnancy are health issues that arise during pregnancies which can involve the health of the mother, the fetus, and/or both. Amongst these complications are, anemia (which can occur due to malnutrition), ectopic pregnancy (a condition when a fertilized egg develops outside of the uterus, usually in a fallopian tube), fetal problems (which can include poor growth or heart problems), and gestational diabetes (too high blood sugar levels during pregnancy). Other issues that can occur are infections such as toxoplasmosis (an infection caused by a parasite found in cat feces, soil, and raw/undercooked meat). Preventive measures for this infection include washing hands with soap and water, and washing produce before eating. After hurricane Maria, about 1 million of Puerto Ricans residents were left without reliable drinking water and thus don’t have the basic resources needed in order to prevent such infections. Most of the other pregnancy complications mentioned can be treated and/or prevented with access to proper medical attention, and medicine but for this to be possible, access to medical sites and healthcare coverage is essential. The inability to acquire such necessities are directly attributed to poverty levels and lack of funding in the island and they attribute to mental illnesses such as depression. Within the general population in Puerto Rico 7.3% of Puerto Rican adults ages 18-64 have reported suffering from mental illness. Additionally, 2 out of 10 report suffering from some kind of psychiatric ailment and 1 out of 10 suffers from depression. 23.7% of individuals abuse a combination of drugs and alcohol. Unfortunately, 4 out of every 10 Puerto Ricans who suffer from mental illness do not receive any treatment. Amongst this population are pregnant women; pregnant women who experience mental illness do not receive proper medical attention. Within these women, those who are experiencing mental illnesses might not know it due to poor education and not receive appropriate care. 7.4% of Puerto Ricans reported not having access to healthcare in the 2016 census.[36][37]

Post Pregnancy issues

Postpartum depression and Postpartum psychosis are common amongst new mothers. Postpartum depression, a depressive state that involves feelings of sadness, lack of interest, feeling like a bad mother and fear of harming the baby, is a condition that must be treated promptly. Postpartum psychosis is a more severe condition where new mothers will experience delusions and hallucinations; this condition must be treated immediately as it can be harmful for both the mother and the baby. Postpartum depression has a prevalence rate of 6%-13% and postpartum physcosis a rate of 1-2%. However, women in Puerto Rico report having symptoms of postpartum psychosis and never have knowing that they were depressed. Moreover, many Puerto Rican women have reported not having the knowledge and or accessibility to receive care.[36][38]

Religion

There are many religious beliefs represented in the island with Christianity as the religion indicated by the majority in 2010.

Religious breakdown in Puerto Rico (2010):[39]

Christians

A recent report providing a full breakdown as to specific religions is not available; the most recent was for 2006.

The Christian Denominational Breakdown was as follows in 2006:[40]

| Denomination | Adherents |

|---|---|

| Catholic | 1,650,000 |

| Other Pentecostal | 229,814 |

| Pentecostal Church of God | 100,000 |

| Assemblies of God | 56,000 |

| Baptist Convention | 35,000 |

| Seventh-day Adventist | 31,524 |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 25,778 |

| Church of God (Cleveland) | 17,500 |

| Defenders of the Faith | 17,500 |

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints | 16,084 |

| Disciples of Christ | 10,778 |

| United Methodist | 10,000 |

| Boriquen Presby Synod | 8,300 |

| Christian and Missionary Alliance | 6,500 |

| Church of the Nazarene | 2,994 |

| Other | 130,400 |

Catholics

The Roman Catholic Church has been historically the most dominant religion of the majority of Puerto Ricans, with Puerto Rico having the first dioceses in the Americas.[41] This religion was brought by Spanish colonists. The first dioceses in the Americas, including that of Puerto Rico, were authorized by Pope Julius II in 1511.[42] One Pope, John Paul II, visited Puerto Rico in October 1984. All municipalities in Puerto Rico have at least one Catholic Church, most of which are located at the town center or "plaza".

An Associated Press article in March 2014 stated that "more than 70 percent of whom identify themselves as Catholic" but provided no source for this information. (It may have been using the 2010 Pew Research Center data.)[43]

The CIA World Factbook however, reports that 85% of the population of Puerto Rico identifies as Roman Catholic, while 15% identify as Protestant and Other. Neither a date or a source for that information is provided and may not be recent.[44]

In November 2014, a Pew Research report, with the sub-title Widespread Change in a Historically Catholic Region, indicated that only 56% of Puerto Ricans were Catholic and that 33% were Protestant. This survey was completed between October 2013 and February 2014.

Protestants

Protestantism was suppressed under the Spanish Catholic regime. For example, the Holy Trinity Anglican church in Ponce, was prevented from ringing its bell until 1898, when American troops landed there.[45] Protestantism increased under American sovereignty, making contemporary Puerto Rico more interconfessional than in previous centuries, although Catholicism continues to be the dominant religion. The first Protestant church, Iglesia de la Santísima Trinidad, was established in Ponce by the Anglican Diocese of Antigua in 1872.[46] It was the first non-Roman Catholic Church in the entire Spanish Empire in the Americas.[47][48]

Muslims

In 2007, there were over 5,000 Muslims in Puerto Rico, representing about 0.13% of the population.[49][50] There are eight Islamic mosques spread throughout the island, with most Muslims living in Río Piedras.[51][52] Puerto Rican converts to Islam continue to occur.[53] "Ties between Latinos and Islam are more than just spiritual, but date back to Spanish history. Many people do not realize that Muslims conquered Spain killing many Christians for more than 700 years".[54] And at times not just individuals, but whole families convert. However, lack of Muslim education in the Island forces some Puerto Rican Muslims to migrate to the States.[54] Islam was brought into Puerto Rico mainly via the Palestinian migration of the 1950s and '60s.[55] Thus, today there is a strong Palestinian presence among Muslims in Puerto Rico. "They are economically strong and are thus able to pay for a full-time Imaam".[56]

Jews

Puerto Rico is also home to the largest Jewish community in the Caribbean with 3,000 Jewish inhabitants.[57] Some Puerto Ricans have converted, not only as individuals but as entire families. Puerto Rico is the only Caribbean island in which the Conservative, Reform and Orthodox Jewish movements are represented.[7][58]

Other religious practices

Taíno religious practices have been rediscovered/reinvented by a handful of advocates. Starting in about 1840, there have been attempts to create a quasi-indigenous Taíno identity in rural areas of Puerto Rico.[59] This trend accelerated among the Puerto Rican community in the mainland United States in the 1960s.[60] In the 2010 U.S. census, 9,399 people are identified as "Taíno."[61]

Various African religious practices have been present since the arrival of enslaved Africans. In particular, the Yoruba beliefs of Santería and/or Ifá, and the Kongo-derived Palo Mayombe (sometimes called an African belief system, but rather a way of Bantu lifestyle of Congo origin) find adherence among the few individuals who practice some form of African traditional religion.

Demographic statistics

The following demographic statistics are from the CIA World Factbook unless otherwise indicated.

Population in 2010:

- 3,725,789 (2010 U.S. Census)

Population in 2016:

Gender:[64]

- Men: 1,785,171

- Women: 1,940,618

Age structure:

- 0–17 years:

- 24.2% (903,295)

- 18–24 years:

- 10.1% (375,175)

- 25–34 years:

- 13.2% (492,332)

- 35–49 years:

- 19.6% (731,514)

- 50–64 years:

- 18.3% (681,505)

- 65 years and over:

- 14.6% (541,998)

Infant mortality rate:

- Total

- 8.23 deaths/1,000 live births

- Male

- Deaths/1,000 live births

- Female

- 7.43 deaths/1,000 live births (2010 est.)

Life expectancy at birth:

- Total population:

- 78.77 years

- Male:

- 75.15 years

- Female:

- 82.57 years (2010 est.)

Total fertility rate:

- 1.62 children born/woman (2010 est.)

Nationality:[65]

- Noun: Puerto Rican(s) (US citizens)

- Adjective: Puerto Rican

Ethnic Groups (2010):[65]

- White 75.8%

- Black/African 12.4%

- Other 8.5% (includes American Indian, Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian, Other Pacific Islander, and Others)

- Mixed 3.3%

Religions:[39]

- Roman Catholic 69.7%

- Protestant and Other Christian 27%

Languages:[65]

Median Household Income:[63]

- $19,350 (2015 est.)

Individuals below the poverty level:[63]

- 45.5% (2015 est.)

Education, high school graduate or higher:[63]

- 73% (2015 est.)

See also

- Puerto Rican people

- Demographics of the United States

- Cultural diversity in Puerto Rico

- Puerto Rican citizenship

- Outline of Puerto Rico

- Cultural diversity in Puerto Rico

- Index of Puerto Rico-related articles

- History of women in Puerto Rico

- Military history of Puerto Rico

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Puerto Rico

- Homelessness in Puerto Rico

References

- ↑ "Puerto Rico Population History, 1765–2000". Welcome.topuertorico.org. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "Resident Population Data". Census. US: Government. 2010. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "State Totals: Vintage 2017". Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Stacy., Taus-Bolstad, (2005-01-01). Puerto Ricans in America. Lerner Publications Co. ISBN 9780822539537. OCLC 54046670 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Puerto Rico – History and Heritage". Smithsonianmag.com. Smithson Institution. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ 1969–, Brown, Monica, (2002-01-01). Gang nation : delinquent citizens in Puerto Rican, Chicano, and Chicana narratives. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816634785. OCLC 48649774.

- 1 2 "Puerto Rico Virtual Jewish History Tour". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ B.R. Mitchell. International historical statistics: the Americas, 1750–2000.

- ↑ "United Nations Statistics Division – Demographic and Social Statistics". Unstats.un.org. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-09-27. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-16. Retrieved 2017-10-03.

- ↑ "Births: Final Data for 2016" (PDF). Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ "Vital Statistics Rapid Release - State and National Provisional Counts". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ "United Nations Statistics Division – Demographic and Social Statistics". Unstats.un.org. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "World Population Prospects – Population Division – United Nations". Retrieved 2017-07-15.

- ↑ "Puerto Rico's History on race" (PDF). Ssc.wisc.edu. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- 1 2

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ 2010.census.gov Archived March 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Racial Amnesia". 3 March 2016. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "Mitochondrial DNA analysis reveals substanial Native American ancestry in Puerto Rico Human Biology – Find Articles". 8 June 2007. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ Not of Pure Blood. Jay Kinsbruner. Duke University Press. 1996. Page 22. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ "How Puerto Rico became white" (PDF). Ssc.wisc.edu. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "Race and Hispanic Origin, Puerto Rico". US Census. US Department of Commerce. 2016. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ↑ "Ethnicity 2000 census" (PDF). Topuertorico.org. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "Largest ethnic groups in Puerto Rico". Names.mongabay.com. 3 March 2004. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ 2006–2008 Three Year Estimate. Puerto Rico Community Survey;Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race. Archived June 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Path: U.S. Census Bureau > Fact Sheet > United States > Puerto Rico > 2006–2008 tab > ACS Demographic Estimates. Retrieved June 19, 2010.

- ↑ Tang, H; Choudhry, S; Mei, R; Morgan, M; Rodriguez-Cintron, W; Burchard, EG; Risch, NJ (2007). "Recent genetic selection in the ancestral admixture of Puerto Ricans". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81: 626–33. doi:10.1086/520769. PMC 1950843. PMID 17701908.

- ↑ Martínez Cruzado, Juan C. (2002). "The Use of Mitochondrial DNA to Discover Pre-Columbian Migrations to the Caribbean: Results for Puerto Rico and Expectations for the Dominican Republic". KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology [On-line Journal], Special Issue, Lynne Guitar, Ed. Available at: "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-06-22. Retrieved 2008-07-14. [Date of access: 25 September 2006]

- ↑ Bonilla et al., Ancestral proportions and their association with skin pigmentation and bone mineral density in Puerto Rican women from New York City. Hum Gen (2004) 115: 57–58 Available at: "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-14. Retrieved 2014-03-30. [Date of access: 30 May 2008]

- ↑ Gottschling, Marc; Irimia, Ramona-Elena (8 June 2016). "Taxonomic revision of Rochefortia Sw. (Ehretiaceae, Boraginales)". Biodiversity Data Journal. 4: e7720. doi:10.3897/BDJ.4.e7720.

- ↑ https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/PR/PST045216

- ↑ https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-rico-s-exodus-doctors-adds-health-care-strain-dire-n783776

- ↑ Documenting the Myth of Taino Extinction. Dr. Lynne Guitar. KACIKE: Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology. Retrieved May 23, 2010. Archived June 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Li, Rui; Simmons, Katharine B.; Bertolli, Jeanne; Rivera-Garcia, Brenda; Cox, Shanna; Romero, Lisa; Koonin, Lisa M.; Valencia-Prado, Miguel; Bracero, Nabal (2017-01). "Cost-effectiveness of Increasing Access to Contraception during the Zika Virus Outbreak, Puerto Rico, 2016". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (1): 74–82. doi:10.3201/eid2301.161322. ISSN 1080-6040. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Puerto Rico". Census Bureau QuickFacts. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ "Pregnancy complications | womenshealth.gov". womenshealth.gov. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ "Critical State of Mental Health in Puerto Rico". El Nuevo Dia (in Spanish). 2017-01-16. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- 1 2 3 "Demography – Puerto Rico". Pew Research. Pew Research, DC. January 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ↑ Denominations Retrieved June 9, 2009. Archived January 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Porto Rico". En.wikisource.org. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑

- ↑ Associated Press (March 12, 2014). "Catholic Church and Puerto Rico officials at odds in widening sex abuse investigation". FOX News. FOX News. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Puerto Rico – People and Society". CIA Library. CIA. 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

Roman Catholic 85%, Protestant and other 15%

- ↑ "Religion in Puerto Rico – By Puerto Rico Channel". Puertorico.com. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "Sobre Nosotros". Episcopalpr.org. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ↑ Luis Fortuño Janeiro. Album Histórico de Ponce (1692–1963). Page 165. Ponce, Puerto Rico: Imprenta Fortuño. 1963.

- ↑ "La presencia Germanica en Puerto Rico". Preb.com. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ↑ Institute of Islamic Information and Education: Number of Muslims and Percentage in Puerto Rico Retrieved June 11, 2009. Corrected October 6, 2009.

- ↑ Percent Puerto Rican population that are Muslims Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ↑ Muslim mosques in Puerto Rico Archived August 5, 2012, at Archive.is Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ↑ "Saudi Aramco World : Muslims in the Caribbean". Saudiaramcoworld.com. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "Puerto Rican Converts". Discoveringislam.org. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- 1 2 Reshaping One Nation Under God Retrieved June 8, 2009. Archived May 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Palestinian migration Retrieved June 8, 2009. Archived October 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-23. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ "The Jewish Palate: The Jews of Puerto Rico". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ↑ "Luxner – Articles". Luxner.com. Archived from the original on 2005-11-07. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ "Taíno: Indigenous Caribbeans - Black History Month 2017". Black History Month 2017. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ↑ Alexandra Aikhenvald (2012) Languages of the Amazon, Oxford University Press

- ↑ "American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010 (CPH-T-6)". Census.gov. Census bureau. 2010. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Population Estimates, Population Change, and Components of Change". US Census. US Census. January 12, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016 (NST-EST2016-01)

- 1 2 3 4 "Fact Finder, Puerto Rico". US Census. Department of Commerce. 2016. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ↑ "2006 Survey Archived June 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 "Central America and Caribbean :: PUERTO RICO". CIA The World Factbook.

Bibliography

- "Population and Society in Puerto Rico from the Spanish Colonial Era to 1940: A Select Bibliography". Caribbean Studies. University of Puerto Rico. 35 (2). 2007. ISSN 0008-6533. JSTOR 25613118.

External links

- The End of Slavery ...

- How Puerto Rico Became White: Racial analysis

- Puerto rico 2005 Fact finder statistics

- United Nations country profile

- Genetic Make-up of Puerto Ricans

- 1930s Sterilization of One Third of Puerto Rican Women by the Chicago Women's Liberation Union