Cold-weather warfare

| Cold-weather warfare |

|---|

|

Cold-weather warfare, also known as Arctic warfare or winter warfare, encompasses military operations affected by snow, ice, thawing conditions or cold, both on land and at sea. Cold-weather conditions occur year-round at high elevation or at high latitudes, and elsewhere materialise seasonally during the winter period. Mountain warfare often takes place in cold weather or on terrain that is affected by ice and snow, such as the Alps and the Himalayas. Historically, most such operations have been during winter in the Northern Hemisphere. Some have occurred above the Arctic Circle where snow, ice and cold may occur throughout the year. At times, cold or its aftermath—thaw—has been a decisive factor in the failure of a campaign, as with Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812 and the German invasion of Russia during World War II.

History

Northern and Eastern Europe were the venues for some well-documented winter campaigns. During World War II several actions took place above the Arctic Circle. Recent cold-weather conflicts have occurred in the Himalayas.

Pre–1800

In 1242, the Teutonic Order lost the Battle on the Ice on Lake Peipus to Novgorod. In 1520, the decisive Battle of Bogesund between Sweden and Denmark occurred on the ice of lake Åsunden.[1]

Sweden and Denmark fought several wars during the 16th and 17th centuries. As a great deal of Denmark consists of islands, it was usually safe from invasion, but in January 1658, most of the Danish waters froze. Charles X Gustav of Sweden led his army across the ice of the Belts to besiege Copenhagen. The war ended with the treaty of Roskilde, a treaty very favorable to the Swedish.[2]

During the Great Northern War, Swedish king Charles XII set off to invade Moscow, but was eventually defeated at the Battle of Poltava after being weakened by cold weather and scorched earth tactics. Sweden suffered more casualties during the same war as Carl Gustaf Armfeldt with 6,000 men tried to invade Trondheim. Three thousand of them died of exposure in the snow during the Carolean Death March.[3]

19th century

During the Finnish War, the Russian army unexpectedly crossed the frozen Gulf of Bothnia from Finland to the Åland Islands and, by 19 March 1809, reached the Swedish shore within 70 km from the Swedish capital, Stockholm. This daring maneuvre decided the outcome of the war.[4]

Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812 resulted in retreat in the face of winter[5] with the majority of the French army succumbing to frostbite and starvation, rather than combat injuries.[6]

20th century

The Finnish Army used ski troops during the Winter War and the Second World War, where the numerically dominant Soviet forces had a hard time fighting mobile, white-clad ski soldiers.[7]

In Operation Barbarossa in 1941, both Russian and German soldiers had to endure terrible conditions during the Russian winter. The German-Finnish joint offensive against Murmansk (Operation Silver Fox) in 1941 saw heavy fighting in the Arctic environment. Subsequently, the Petsamo-Kirkenes Operation conducted by the Red Army against the Wehrmacht in 1944 in northern Finland and Norway drove the Germans out of there. In late 1944, Finland turned against their former cobelligerents, Nazi Germany, under the Soviet Union's pressure and pressured the Germans to withdraw in the ensuing Lapland War.[8] While use of ski infantry was common in the Red Army, Germany formed only one division for movement on skis.[7] From June 1942 to August 1943, the United States and Canada fought the Japanese in the Aleutian Islands Campaign in the Alaska Territory.[9]

The Battle of Chosin Reservoir was a stark example of cold affecting military operations in the Korean War. There were many cold injuries and malfunctions of materiel, both vehicles and weapons.[10][11]

The Siachen conflict is a military conflict between India and Pakistan over the disputed Siachen Glacier region in Kashmir. The conflict began in 1984 with India's successful Operation Meghdoot during which it gained control over all of the Siachen Glacier.[12] A cease-fire went into effect in 2003.[13]

World War II in the Arctic

The following actions were fought in the Arctic by land and naval forces between 1941 and 1945 in the following theaters of operations:

Arctic Ocean

- The raid on Kirkenes and Petsamo (Operation EF) took place on 30 July 1941 when the British Fleet Air Arm launched an unsuccessful raid from the aircraft carriers HMS Victorious and Furious to inflict damage on merchant vessels owned by Germany and Finland and to show support for Britain's new ally, the Soviet Union.[14]

- Operation Rösselsprung (bobsledding) was a plan by the German Kriegsmarine to intercept an arctic convoy in mid-1942, resulting in the near destruction of Convoy PQ 17.[15]

- Operation Wunderland (wonderland) was a large-scale operation undertaken in summer 1942 by the Kriegsmarine to enter the Kara Sea during the summer thaw and destroy as many Russian vessels as possible.[15]

Finland

The Winter War was a military conflict between the Soviet Union (USSR) and Finland. It began with a Soviet invasion of Finland on 30 November 1939, three months after the outbreak of World War II, and ended three and a half months later with the Moscow Peace Treaty on 13 March 1940.

The Lapland War was fought between Finland and Germany from September 1944 to April 1945 in Finland's northernmost Lapland Province. It included:[16]

- Operation Birke (birch) was a German operation late in World War II in Finnish Lapland to protect access to nickel.[17]

- Operation Nordlicht (northern lights) was a German scorched-earth retreat operation in Finland during the end of World War II.[18]

- The Petsamo–Kirkenes Offensive was a major military offensive during World War II, mounted by the Red Army against the Wehrmacht in 1944 in northern Finland and Norway.[19]

Norway

- The liberation of Finnmark was a military operation, lasting from 23 October 1944 until 26 April 1945, in which Soviet and Norwegian forces wrestled away control of Finnmark, the northernmost county of Norway, from Germany. It started with a major Soviet offensive that liberated Kirkenes.[20]

Northern Russia

- Operation Silver Fox was a joint German–Finnish military operation offensive during World War II. Its main goal was to cut off and ultimately capture the key Soviet port at Murmansk through attacks from Finnish and Norwegian territory.[21]

Spitsbergen

- Operation Gauntlet was a Combined Operations raid by Canadian troops, with British Army logistics support and Free Norwegian Forces servicemen on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, 600 miles south of the North Pole, from 25 August to 3 September 1941.[22]

- Operation Fritham was a Norwegian military operation, based from British soil, that had the goal of securing the rich coal mines on the island of Spitsbergen (a part of Svalbard) and denying their use to Nazi Germany.[23]

- Operation Zitronella (Citronella) was an eight-hour German raid on Spitzbergen on 8 September 1943.[24] This marks the highest latitude at which a land battle has ever been fought. However, given the extreme conditions, the German and Allied troops were at times compelled to assist each other to survive.[25]

Historical lessons learned

In his 1981 paper, Fighting the Russians in Winter: Three Case Studies, Chew draws on experiences from the Allied-Soviet War in Northern Russia during the Winter of 1918–19, the destruction of the Soviet 44th Motorized Rifle Division, and Nazi–Soviet Warfare during World War II to derive winter warfare factors pertaining to military tactics, materiel and personnel:[26]

- Tactics – Defensive positions are highly advantageous because of the ability to maintain warmth and protection, compared to attacking in extreme cold. Mobility and logistical support are often restricted by snow, requiring plowing or compacting it to accommodate wide-tracked vehicles or sleds. Infantry movement in deep snow requires skis or snowshoes to avoid exhaustion. Sound carries well over crusted snow, diminishing the element of surprise. Explosives are useful for excavating foxholes and larger shelters in frozen ground. Attacking field kitchens and encampments deprives the enemy of food and shelter. Rapid removal of the wounded from the battlefield is essential to their survival in the cold.

- Materiel – Weapons and vehicles require special lubricants to operate at low temperatures. Mines are unreliable in winter, owing to deep snow that may cushion the fuse or form an ice bridge over the detonator.

- Personnel – Proper winter clothing is required to maintain body heat and to avoid such cold injuries as frostbite. Troop efficiency and survival requires either making use of available shelter or providing portable shelter.

Operational factors – land

Operational factors encompass planning for the climate and weather in which military operations are required with snow, ice, mud and cold being the primary considerations. Military tactics, materiel, combat engineering and military medicine all require specialized adaptations to the conditions encountered in cold weather. The Red Army was an early adopter of a protocol for winter warfare.[27]

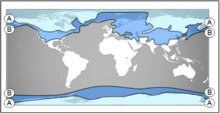

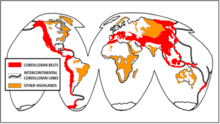

Cold and mountainous regions

In its 2016 "Mountain Warfare and Cold Weather Operations" manual, the US Army defines cold regions as "where cold temperatures, unique terrain, and snowfall have a significant effect on military operations for one month or more each year." It describes regions that are either severely cold or moderately cold, each comprising about approximately one quarter of the Earth's land mass.[28]

- Severely cold – Where mean annual air temperatures stay below freezing, maximum snow depths exceed 60 centimetres (24 in), and ice covers lakes and rivers for more than 180 days each year.

- Moderately cold – Where the mean temperatures during the coldest month are below freezing.

The manual also delineates the principal mountain ranges of the world, which lie along the broad belts, which encircle the Pacific basin and then lead westward across Eurasia into North Africa. Secondarily, rugged chains of mountains lie along the Atlantic margins of the Americas and Europe.

Weather conditions

Temperature, wind, snow, and thaw are the primary conditions that affect the winter battlescape.

Temperature

The US Army groups cold temperatures using categories. The temperature categories are (with quoted summaries):[28]

- Wet cold – From 39 to 20 °F (4 to −7 °C). Wet cold conditions occur when wet snow and rain often accompany wet cold conditions. This type of environment is more dangerous to troops and equipment than the colder, dry cold environments because the ground becomes slushy and muddy and clothing and equipment becomes perpetually wet and damp.

- Dry cold – From 19 to −4 °F (−7 to −20 °C). Dry cold conditions are easier to live in than wet cold conditions. Like in wet cold conditions, proper equipment, training and leadership are critical to successful operations. Wind chill is a complicating factor in this type of cold. The dry cold environment is the easiest of the four cold weather categories to survive in because of low humidity and the ground remains frozen. As a result, people and equipment are not subject to the effects of the thawing and freezing cycle, and precipitation is generally in the form of dry snow.

- Intense cold – From −5 to −25 °F (−21 to −32 °C). This temperature range can affect the mind as much as the body. Simple tasks take longer and require more effort than in warmer temperatures and the quality of work degrades as attention-to-detail diminishes. Clothing becomes more bulky to compensate for the cold so troops lose dexterity. Commanders consider these factors when planning operations and assigning tasks.

- Extreme cold – From −25 to −40 °F (−32 to −40 °C). In extreme cold the challenge of survival becomes paramount as personnel withdraw into themselves. Weapons, vehicles and munitions are likely to fail in this environment.

- Hazardous cold – From −40 °F (−40 °C) and below. Units require extensive training before operating in these temperature extremes.

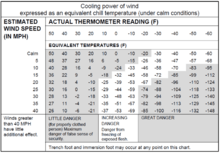

The combined cooling effect of ambient temperature and wind (wind chill) is an important factor that affects troops.

Snow

For military purposes, the US Army categorizes snow as light, moderate, or heavy. Each classification affects visibility and ground movement due to accumulation and is quoted below:[28]

- Light snow – Visibility is equal to or greater than 5⁄8 mile (1,000 m) in falling snow. A trace to one inch (2.5 cm) per hour accumulates.

- Moderate snow – Visibility is 5⁄16 to 1⁄2 mile (500 to 800 m) in falling snow. One to three inches (2.5 to 7.6 cm) per hour accumulates.

- Heavy snow – Visibility is less than 1⁄4 mile (400 m) in falling snow. Three inches (7.6 cm) or more inches per hour accumulates.

Snow and snowdrifts can create advantages on the battlefield by filling in ditches and vehicle tracks and flattening the terrain. It also creates hollows on the downwind side of obstacles, such as trees, buildings, and bushes, which provide observation points or firing positions. Snowdrifts may provide cover for soldiers to approach an objective.[28] Soviet doctrine cited 30 centimetres (12 in) as the threshold snow depth that impairs mobility for troops, cavalry and vehicles, except tanks for which the threshold was 50 centimetres (20 in).[27]

Thaw

.jpg)

Thawing conditions can impair mobility and put soldiers at risk of trench foot by creating mud on the ground and by the weakening and breakup ice cover on bodies of water. Maintaining roads becomes more difficult during spring thaw run off and requires mud removal by heavy equipment. Slushy and muddy ground causes clothing and equipment to become wet, damp and dirty.[28] Muddy conditions greatly inhibited Napoleon's ability to maneuver in Russia[29] and also the German attempt to take Moscow in World War II.[30]

Tactics

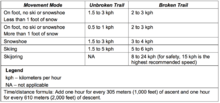

The dominant tactical concern in cold conditions is the ability to maneuver in vehicles or on foot. Additionally, during winter, night operations become the norm at higher latitudes with their long periods of darkness.[28] Snow enhances night vision because of high reflectivity and the visibility of combatants against the white background.[27]

Mounted movement – Over snow-covered terrain vehicles may be employed to establish and maintain trails by establishing a well concealed track with the first vehicle, followed by a vehicle traveling offset from the track of the first, to flatten the trail, and subsequent vehicles widening and flattening the trail. Marked trails avoid obliteration in snowstorms or drifting conditions. In mountainous terrain, tracked vehicles, including tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, and cavalry fighting vehicles, rarely accompany dismounted infantry in the assault. Instead, they assist forces by occupying positions where they can use their firepower to isolate enemy objectives.[28]

Dismounted movement – Troops moving in a wedge-like "column" formation travel more slowly, with no one breaking the trail in undisturbed snow, than the in-line file formation. Therefore, column formation is reserved for imminent enemy contact. As slope angle increases, the amount of travel time is likely to increase substantially.[28]

Water crossings – According to the US Army, rivers found in cold regions may be major obstacles. Subarctic rivers usually have many braided channels and swift currents. During spring and early winter, rivers may become impassable due to freezing or thawing ice flows. Once firmly frozen, rivers may offer routes for both mounted and dismounted movement. Some swampy areas do not freeze solidly during the coldest periods of winter to support troop movements. Nonetheless, it is possible to construct "ice bridges" to thicken an iced-over waterway, using pumps or some other means of flooding the ice-covered area, when temperatures are below −12 °C (10 °F) and the pre-existing natural ice is thicker than 10 centimeters (four inches) to support the construction activity.[28] Red Army doctrine suggested the use of frozen lakes and rivers as expeditionary airfields, located close to the front to take advantage of short daylight hours in winter.[27]

Soviet doctrine emphasized the importance of camouflage over positions and the need to remove telltale signs of artillery actions, such as smoke stains or shell casings. It also cited the usefulness of decoy targets. It describes the establishment of breastworks made from snow 2 to 3 metres (7 to 10 ft) thick, ice 1.5 metres (5 ft) thick or soil and wood 0.9 metres (3 ft) thick.[27]

Snow camouflage

Armies have made use of improvised and official snow camouflage uniforms and equipment since the First World War, such as in the fighting in the Dolomite Mountains between Austria and Italy.[32][33] Snow camouflage was used far more widely in the Second World War by the Wehrmacht, the Finnish Army, the Red Army and others.[34][35][36][37] Since then, snow variants of disruptively patterned camouflage for uniforms have been introduced, sometimes with digital patterns. For example, the Bundeswehr has a Schneetarn (snow) variant of its widely used Flecktarn pattern.[38]

Materiel

Snow, ice and cold temperatures affect munitions and military vehicles.

Munitions – Snow, ice, frozen ground, and low temperatures affect mine-laying operations. Burying mines in a frost layer may be difficult, requiring mines to be placed on top of the ground and then camouflaged. Snow or ice may prevent detonation, owing to freezing the firing device or isolating from pressure above. This can be mitigated with plastic laid over the top of the mine.[28]

Vehicles – Adaptations of military vehicles to winter operations include tire chains for maintaining traction of wheeled vehicles. Diesel engines start less well in cold and may require pre-heating or idling during cold periods.[28] A variety of military vehicles have been developed for over-snow travel, including the Sisu Nasu,[39] BvS 10,[40] and M29 Weasel.[41]

Military engineering

Military engineers design and construct transportation and troop-support facilities.[28] Red Army doctrine gave them the responsibility to establish build and maintain routes, including water crossings, build and destroy obstacles that require special equipment, construct and maintain airfields, and to build shelter for personnel. Operations that didn't require special equipment were left to other troops.[27]

In cold climates frozen ground can make digging difficult. It's often necessary to use local materials, if suitable, for construction. Engineers must provide roadways, landing zones, shelter, water supply and wastewater disposal, and electrical power to encampments. Roadway and landing zones require heavy equipment, which is more fatiguing to operate in the cold and necessary to protect from freezing. Snowstorms require cleanup and spring thaw requires management of thawed soil. Landing zones require stabilization of dust and snow to avoid blinding helicopter pilots. The US Army has cold-weather adaptive kits for providing water and electrical utilities. The tactical engineer has limited options for providing a water supply; they are in order of ease of provision: drawing water from rivers or lakes, melting ice or snow, or drilling wells.[28]

Water supply and treatment is especially challenging in the cold. US Army tactical water purification systems require a winter kit operate between 32 and −25 °F (0 and −32 °C). Water storage may require heating. Water source exploitation may require angering through ice, if shaped charges are not available. The water distribution system can be subject to freezing and clogging from frazil ice. Where chemical treatment is used, it takes longer to dissolve in the treated water.[28]

Medicine

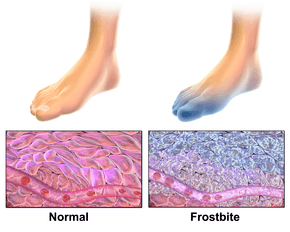

Three types of cold injury can occur in the theater, hypothermia, trench foot, and frostbite in ascending amount of exposure to cold temperatures.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia occurs when the body core temperature drops below 35 °C (95 °F). Symptoms depend on the temperature and range from shivering and mental confusion to increased risk of the heart stopping. The treatment of mild hypothermia involves warm drinks, warm clothing and physical activity. In those with moderate hypothermia heating blankets and warmed intravenous fluids are recommended. People with moderate or severe hypothermia should be moved gently. In severe hypothermia extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or cardiopulmonary bypass may be useful. In those without a pulse cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is indicated along with the above measures. Rewarming is typically continued until a person's temperature is greater than 32 °C (90 °F). Adequate insulation from clothing is the best way to avoid hypothermia in the field.[42]

Trench foot

Trench foot is a medical condition caused by prolonged exposure of the feet to damp, unsanitary, and cold conditions at temperatures as warm as 16 °C (61 °F) for as few as 13 hours. Exposure to these environmental conditions causes deterioration and destruction of the capillaries and leads to morbidity of the surrounding flesh.[43] Affected feet may become numb, affected by erythema (turning red) or cyanosis (turning blue) as a result of poor blood supply, and may begin emanating a decaying odour if the early stages of necrosis (tissue death) set in. As the condition worsens, feet may also begin to swell. Advanced trench foot often involves blisters and open sores, which lead to fungal infections. If left untreated, trench foot usually results in gangrene, which may require amputation. If trench foot is treated properly, complete recovery is normal, though it is marked by severe short-term pain when feeling returns. Trench foot affected tens of thousands of soldiers engaged in trench warfare in World War I. Keeping feet warm and dry, or at least changing into warm and dry replacement footgear, is the best way to avoid trench foot.[44]

Frostbite

Frostbite is localized damage to skin and other tissues due to freezing. At or below 0 °C (32 °F), blood vessels close to the skin start to constrict, and blood is shunted away from the extremities. The same response may also be a result of exposure to high winds. This constriction helps to preserve core body temperature. In extreme cold, or when the body is exposed to cold for long periods, this protective strategy can reduce blood flow in some areas of the body to dangerously low levels. This lack of blood leads to the eventual freezing and death of skin tissue in the affected areas. Frostbite was responsible for over one million casualties in wars in the 20th century. Adequate insulation from clothing is the best way to avoid hypothermia in the field.[44]

Training by nation

The following nations report regular training programs in cold-weather warfare:

- Canada – In 2008, the Canadian Forces established the Nanisivik Naval Facility, a winter warfare training center above the arctic circle in Resolute, Nunavut[45] for annual exercises.[46]

- China – The People's Liberation Army trains annually in regions subject to harsh winter conditions. Lightly armed border patrol units are mounted on horseback or snowmobiles and are expected to provide early detection of incursion.[47]

- Finland – The Finnish Defence Forces trains every conscript for skiing and Arctic warfare regardless of the branch, approximately 25,000 soldiers per year.[48] Finland also trains US Army trainers in Arctic warfare.[49]

- India – The Indian Army trains 100 officers and 400 non-commissioned officers and junior commissioned officers annually, at its High Altitude Warfare School. Its graduates are assigned to the Siachen Glacier border confrontation.[50]

- Iran – Members of the 65th Airborne Special Forces Brigade train for warfare on snow at their winter camp in Emamzadeh Hashem, Iran.[51]

- Norway – Hosts an annual, multi-national winter exercise Cold Response course. In 2016, the participants came from Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Latvia, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, the USA, the United Kingdom and Norway.[52]

- Russian Federation – Russia trains combined forces in winter annually. In 2013, it held four winter readiness exercises under shorter-than-usual notice, according to Wilk: A February exercise with seven thousand soldiers, several hundred fighting vehicles and 48 aircraft and helicopters and three March exercises, one using seven thousand soldiers, 250 fighting vehicles, 50 artillery units, 20 aircraft and helicopters as well as 36 warships.[53]

- United Kingdom – Royal Navy sailors and Royal Marines train in Norway above the Arctic Circle.[54]

- United States – The US military maintains cold-weather and mountain warfare training centers at the Army Northern Warfare Training Center at Fort Wainwright, Fairbanks, Alaska, the Army Mountain Warfare School at Camp Ethan Allen, Jericho, Vermont, the Special Forces Command Mountaineering Warfare Training Detachment at Fort Carson, Colorado Springs, Colorado, the US Air Force Arctic Survival School at Eielson AFB, Alaska,[55] and the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center, in Bridgeport, California.[28]

- Cold-weather training exercises

Norwegian Leopard 1A1 tanks participating in a 1982 NATO exercise.

Norwegian Leopard 1A1 tanks participating in a 1982 NATO exercise. Humvees with BGM-71 TOW anti-tank weapons systems in Norway during Operation Cold Winter '87.

Humvees with BGM-71 TOW anti-tank weapons systems in Norway during Operation Cold Winter '87. Norwegian military preparations during Exercise Cold Response, 2009

Norwegian military preparations during Exercise Cold Response, 2009 Royal Marines conducting cold-weather and mountain warfare training in the Himalayas

Royal Marines conducting cold-weather and mountain warfare training in the Himalayas The 202nd Air Defence Brigade in the Western Military District in Russia loading S-300V surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) in 2012.

The 202nd Air Defence Brigade in the Western Military District in Russia loading S-300V surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) in 2012.

Naval operations

_is_submerged_after_surfacing_through_two_feet_of_ice_during_ICEX-07%2C_a_U.S._Navy_and_Royal_Navy_exercise.jpg)

Subfreezing conditions have significant implications for naval operations. The 1988 US Navy Cold Weather Handbook for Surface Ships outlines effects on: icing on the topsides of ships, ship systems, underway replenishment, flight operations, and personnel. It also discusses preparations for cold-weather fleet operations.[56]

Topside icing on ships

Topside icing is a serious hazard to ships operating in sub-freezing temperatures. Thick layers of ice can form on decks, sides, superstructures, deck mounted machinery, antennas and combat systems. The presence of topside ice has many adverse effects, principally it:[56]

- Increases ship displacement

- Decreases freeboard

- Impairs operation of deck machinery

- Impedes personnel movement on deck

- Restricts helicopter operations

- Disrupts operation of radio and radars

Combat systems degradation

Icing may prevent a warship from conducting any type of offensive operations, including restraining the doors of a vertical launch systems, binding gears, shafts, hinges and pedestals. Other effects include sluggish performance of lubricants, increased failure rate of seals, plugs and O-rings, frozen magazine sprinkler systems, excessively long warm-up times for electronics or weapon system electronics, and freeze up of compressed-air-operated components.[56]

Arctic operations

Global climate change has opened the waters of the Arctic along the northern shores of Alaska, Russia and Canada. The region is rich in natural resources. Countries abutting the Arctic Ocean have shown greater military patrol activity. The Military Times reported in 2015 that Russia had reactivated ten military bases, had increased surface ship and aircraft patrols of its Northern Fleet, and had conducted missile tests in the region. The US Navy plans to have sufficient assets by 2030 to respond militarily in the Arctic. As of 2015, it conducted regular submarine patrols, but few air or surface ship operations. Russia had twelve ice breakers versus two for the US.[57] As of 2013, Canada had six ice breakers.[58] In 2016, Canada announced the building of five ice-breaking Arctic and offshore patrol ships.[59]

See also

References

- ↑ Nicolle, David (1996). Lake Peipus 1242: Battle of the Ice. Osprey Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 9781855325531.

- ↑ Herman Lindqvist, När Sverige blev stormakt. Stockholm: Norstedt, 1996. ISBN 978-91-1-932112-1.

- ↑ Oakley, Stewart P. War and Peace in the Baltic, 1560-1790 (Routledge, 2005).

- ↑ Mattila, Tapani (1983). Meri maamme turvana [Sea safeguarding our country] (in Finnish). Jyväskylä: K. J. Gummerus Osakeyhtiö. ISBN 951-99487-0-8.

- ↑ Professor Saul David (9 February 2012). "Napoleon's failure: For the want of a winter horseshoe". BBC news magazine. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ The Wordsworth Pocket Encyclopedia, p. 17, Hertfordshire 1993.

- 1 2 Clemmesen, Michael H.; Faulkner, Marcus, eds. (2013). Northern European Overture to War, 1939–1941: From Memel to Barbarossa. Brill. p. 76. ISBN 978-90-04-24908-0.

- ↑ Ahto, Sampo (1980). Aseveljet vastakkain – Lapin sota 1944–1945 [Brothers in Arms Opposing Each Other – Lapland War 1944–1945] (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kirjayhtymä. ISBN 978-951-26-1726-5.

- ↑ Hays, Otis (2004). Alaska's Hidden Wars: Secret Campaigns on the North Pacific Rim. University of Alaska Press. ISBN 1-889963-64-X.

- ↑ Duncan, James Carl (2013). Adventures of a Tennessean. Author House. p. 190. ISBN 9781481741576.

- ↑ Tilstra, Russell C. (2014). The Battle Rifle: Development and Use Since World War II. McFarland. p. 192. ISBN 9781476615646.

- ↑ Wirsing, Robert. Pakistan's security under Zia, 1977–1988: the policy imperatives of a peripheral Asian state. Palgrave Macmillan, 1991. ISBN 9780312060671.

- ↑ Pervez Musharraf (2006). In the Line of Fire: A Memoir. Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-8344-9. (pp. 68–69)

- ↑ Tovey, Sir John C., Despatch on carrier-borne aircraft attack on Kirkenes (Norway) and Petsamo (Finland) 1941 July 22-Aug.7, p.3175 - 3176

- 1 2 Kemp, Paul (2000). Convoy!: Drama in Arctic Waters. Cassell. ISBN 1-85409-130-1.

- ↑ Nenye, Vesa; Munter, Peter; Wirtanen, Toni; Birks, Chris (2016). Finland at War: the Continuation and Lapland Wars 1941–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1472815262.

- ↑ Lunde, Henrik O. (2011). Finland's War of Choice: The Troubled German-Finnish Alliance in World War II. Newbury: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61200-037-4.

- ↑ Carruthers, Bob (2012). Hitler's Forgotten Armies: Combat in Norway and Finland. Warwickshire: Coda Books Ltd. ISBN 9781781580981.

- ↑ James F. Gebhardt "The Petsamo-Kirkenes Operation: Soviet Breakthrough and Pursuit in the Arctic, October 1944" pp. 75-83

- ↑ "Finnmark Celebrates Liberation from Nazi Occupation with the Help of Russians," The Nordic Page.

- ↑ Mann, Chris M.; Jörgensen, Christer (2002). Hitler's Arctic War. Hersham, UK: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-2899-0.

- ↑ Schuster, Carl O. "Weather War". U.S. Army Aberdeen Test Center. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ↑ Andre Verdenskrig på Svalbard (Svalbard Museum) Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Torkildsen, Torbjørn (1998). Svalbard : vårt nordligste Norge [Svalbard: Our Northernmost Norway] (in Norwegian) (3rd ed.). Oslo: Aschehoug, in cooperation with Det norske svalbardselskap. ISBN 82-03-22224-2. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ Keegan, John (1993). A History of Warfare. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. p. 69. ISBN 0-394-58801-0.

- ↑ Chew, Allen F. (December 1981). "Fighting the Russians in Winter: Three Case Studies" (PDF). Leavenworth Papers. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (5). ISSN 0195-3451. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Armstrong, Richard N.; Joseph G., Welsh (2014), Winter Warfare: Red Army Orders and Experiences, Case series on Soviet military theory and practice, Routledge, p. 208, ISBN 9781135211547, retrieved 2016-12-12

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Headquarters (April 2016). "Mountain Warfare and Cold Weather Operations" (PDF). US Army. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ M. Adolphe Thiers (1864). History of the Consulate and the Empire of France under Napoleon. IV. Translated by D. Forbes Campbell; H. W. Herbert. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. p. 243.

whilst it was almost impossible to drag the gun-carriages through the half-frozen mud

(regarding November 20, 1812) - ↑ Overy, Richard (1997). Russia's War. London: Penguin. pp. 113–114. ISBN 1-57500-051-2.

- ↑ "The Austro-Hungarian Army on the Italian Front, 1915–1918". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ↑ Bull, Stephen (2004). Encyclopedia of Military Technology and Innovation. Greenwood. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-57356-557-8.

- ↑ Englund, Peter (2011). The Beauty And The Sorrow: An intimate history of the First World War. Profile Books. p. 211. ISBN 1-84765-430-4.

- ↑ Brayley, Martin J. (2009). Camouflage uniforms : international combat dress 1940–2010. Ramsbury: Crowood. pp. 37 and passim. ISBN 1-84797-137-7.

- ↑ Peterson, D. (2001). Waffen-SS Camouflage Uniforms and Post-war Derivatives. Crowood. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-86126-474-9.

- ↑ Rottman, Gordon L. (2013). World War II Tactical Camouflage Techniques. Bloomsbury. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-1-78096-275-7.

- ↑ Carruthers, Bob (2013) [28 January 1943]. Wehrmacht Combat Reports: The Russian Front. Pen and Sword. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-1-4738-4534-3.

- ↑ Zäch, Sebastian. "Schneetarn". Bundeswehr (German Army). Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ Hofmann, George F. (1997), PB (United States. Army), United States Armor Association, p. 49

- ↑ Editors (29 April 2016). "Versatile Vikings' £37 million upgrade completed". Gov.UK. Ministry of Defence and Defence Equipment and Support. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ "OSS Briefing Film – The Weasel". Real Military Flix. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ↑ Brown, DJ; Brugger, H; Boyd, J; Paal, P (Nov 15, 2012). "Accidental hypothermia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (20): 1930–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1114208. PMID 23150960.

- ↑ Coughlin, Michael J.; Saltzman, Charles L.; Mann, Roger A. (2013), Mann's Surgery of the Foot and Ankle (9 ed.), Elsevier Health Science, p. 2336, ISBN 9781455748617, retrieved 2016-12-11

- 1 2 Schwartz, Richard B. (2008). Tactical Emergency Medicine. LWW medical book collection. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 319. ISBN 9780781773324. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ Staff (June 23, 2008). "Military's Arctic training facility opens in Resolute". CBC News. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ The Canadian Press (June 23, 2008). "Winter warfare course shows military still struggling in Arctic". CBC News. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ Blasko, Dennis J. (2013). The Chinese Army Today: Tradition and Transformation for the 21st Century. Asian Security Studies. Routledge. p. 312. ISBN 9781136519970. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ↑ Editors (2015). Liikuntakoulutuksen käsikirja (in Finnish). Finnish Defence Forces. p. 288. ISBN 978-951-25-2708-3. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- ↑ Staff (January 15, 2016). "US soldiers practice Arctic warfare in Lapland". Finnish Broadcasting Company. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- ↑ Editors (2001). India: Foreign Policy & Government Guide. Volume 1346 of World Foreign Policy and Government Library. 1. International Business Publications. p. 400. ISBN 9780739782989. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ↑ Editors (April 30, 2016). "Which forces IRGC deployed in Syria?". Islamic World Update. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

The winter training camp is in Emamzadeh Hashem, in which there is a ski resort dedicated to the brigade, used for training snow warfare.

- ↑ "Cold Response 2016". forsvaret.no. Norwegian Armed Forces. 2016. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

Cold Response is the Norwegian Armed Forces' main winter exercise. It is held every other year, and our partners are invited to participate.

- ↑ Wilk, Andrzej (June 26, 2013), "Russian army justifies its reforms" (PDF), OSW Commentary, Warsaw: Centre for Eastern Studies, 109, retrieved 2016-12-11

- ↑ "Cold Weather Training". Royal Navy. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ↑ Rojas, Yash (December 1, 2011). "'Cool School' teaches arctic survival". U.S. Air Force News. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- 1 2 3 Barr, Robert K. (May 1988), US Navy Cold Weather Handbook for Surface Ships (PDF), Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, retrieved 2016-12-13

- ↑ Bacon, Lance M. (February 11, 2015). "Navy prepares for Arctic operations as ice thins". militarytimes.com. Military times. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ↑ Editors (July 24, 2013). "U.S. Coast Guard's 2013 Review of Major Icebreakers of the World". USNI.org. US Naval Institute. Retrieved 2017-03-22.

- ↑ "Arctic/Offshore Patrol Ships". Royal Canadian Navy. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Winter and mountain warfare. |

- Govan, Thomas P. (1946). Training for Mountain and Winter Warfare, Study No. 23. The Army Ground Forces. Historical Section- Army Ground Forces.

- Armstrong, Richard N.; Joseph G., Welsh (2014), Winter Warfare: Red Army Orders and Experiences, Cass series on Soviet military theory and practice, Routledge, p. 208, ISBN 9781135211547, retrieved 2016-12-12