Los Angeles-class submarine

2.jpg) | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders: | |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Sturgeon class |

| Succeeded by: | Seawolf class |

| Cost: | $900 million [1990 prices],[1] ($1.5 billion in 2016 dollars[2]) |

| Built: | 1972–1996 |

| In commission: | 1976–present |

| Completed: | 62 |

| Active: | 32 |

| Retired: | 30 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Nuclear attack submarine |

| Displacement: |

Surfaced: 6,082 tonnes (5,986 long tons) Submerged: 6,927 tonnes (6,818 long tons) |

| Length: | 362 ft (110 m) |

| Beam: | 33 ft (10 m) |

| Draft: | 31 ft (9.4 m) |

| Propulsion: | 1 GE PWR S6G nuclear reactor, 2 turbines 35,000 hp (26,000 kW), 1 auxiliary motor 325 hp (242 kW), 1 shaft |

| Speed: | |

| Range: | Refueling required after 30 years[1] |

| Endurance: | 90 days |

| Test depth: | 800 ft (240 m) |

| Complement: | 129 |

| Sensors and processing systems: | BQQ-5 Suite which includes Active and Passive systems sonar, BQS-15 detecting and ranging sonar, WLR-8V(2) ESM receiver, WLR-9 acoustic receiver for detection of active search sonar and acoustic homing torpedoes, BRD-7 radio direction finder,[6] BPS-15 radar |

| Electronic warfare & decoys: | WLR-10 countermeasures set[6] |

| Armament: | 4× 21 in (533 mm) torpedo tubes, 37× Mk 48 torpedo, Tomahawk land attack missile, Harpoon anti–ship missile, Mk 67 mobile, or Mk 60 Captor mines (FLTII and 688i FLTIII have a 12-tube VLS) |

The Los Angeles class are nuclear-powered fast attack submarines (SSN) in service with the United States Navy. The submarines are also known as the 688 class, after the hull number of lead vessel USS Los Angeles (SSN-688). They represent two generations and close to half a century of the Navy's attack submarine fleet. As of 2018, 35 of the class are still in commission and 27 are retired from service. Of the 27 retired boats, 12 of them were laid up half way (approximately 20 years or less) through their projected lifespans,[1] and another five also laid up early (20–25 years), due to their midlife reactor refueling being cancelled, and one was lost due to a fire. Seven have been scrapped and two are being converted to moored training ships. A further four boats were proposed by the Navy, but later cancelled. The class has more active nuclear submarines than any other class in the world. Submarines of this class are named after American towns and cities, such as Albany, New York, Los Angeles, California or Tucson, Arizona, with the exception of USS Hyman G. Rickover, named for a US Navy Admiral. This was a change from long-standing tradition of naming attack submarines for creatures of the ocean, such as USS Seawolf or USS Shark.

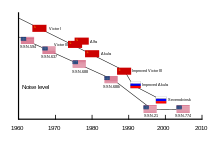

In 1982 after building 31 boats, the class underwent a minor redesign, the following 8 that made up the second "flight" of subs had 12 new vertical launch tubes that could fire Tomahawk missiles. The last 23 saw a significant upgrade with the 688i improvement program. These boats are quieter, with more advanced electronics, sensors, and noise reduction technology. Externally they can be recognized quickly as the retractable diving planes are placed at the bow rather than on the sail.[7]

Design

Capabilities

According to the U.S. Department of Defense, the top speed of the submarines of the Los Angeles class is over 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph), although the actual maximum is classified. Some published estimates have placed their top speed at 30 to 33 knots (56 to 61 km/h; 35 to 38 mph).[4][8] In his book Submarine: A Guided Tour Inside a Nuclear Warship, Tom Clancy estimated the top speed of Los Angeles-class submarines at about 37 knots (69 km/h; 43 mph).

The U.S. Navy gives the maximum operating depth of the Los Angeles class as 650 ft (200 m),[9] while Patrick Tyler, in his book Running Critical, suggests a maximum operating depth of 950 ft (290 m).[10] Although Tyler cites the 688-class design committee for this figure,[11] the government has not commented on it. The maximum diving depth is 1,475 ft (450 m) according to Jane's Fighting Ships, 2004–2005 Edition, edited by Commodore Stephen Saunders of the Royal Navy.[12]

Weapons

_VLS_doors_open.jpg)

Los Angeles-class submarines carry about 25 torpedo tube-launched weapons, as well as Mark 67 and Mark 60 CAPTOR mines and were designed to launch Tomahawk cruise missiles, and Harpoon missiles horizontally (from the torpedo tubes). The last 8 boats of this class also have 12 dedicated vertical launching system (VLS) tubes for launching Tomahawks. The tube configuration for the first two boats differed from the later ones: Providence and Pittsburgh have four rows of three tubes, vs. the inner two rows of four and outer two rows of two tubes found on other examples.

Control systems

Over close to forty years the control suite of the class has changed dramatically. The class was originally equipped with the Mk 113 mod 10 Fire control system, also known as the Pargo display program. The Mk 113 runs on a UYK-7 computer.[13][14]

The Mk 117 FCS, the first "all digital" fire control system replaced the Mk 113. The Mk 117 transferred the duties of the analog Mk 75 attack director to the UYK-7, and the digital Mk 81 weapon control consoles, removing the two analog conversions, and allowing "all digital" control of the digital mk 48 control.[15] The first 688 sub to be built with the Mk 117 was USS Dallas.

The Mark 1 Combat Control System/All Digital Attack Center replaced the Mk 117 FCS which it was based on. The Mk 1 CCS was built by Lockheed Martin, and gave the class the ability to fire Tomahawk missiles.[16] The CSS internal tracker model provides processing for both towed array and spherical array trackers. Trackers are signal followers which generate bearing, arrival angle and frequency reports based on information received by an acoustic sensor. It incorporated the Gyro Static Navigator into the system in replacement of the DMINS of the earlier 688 class.

The Mk 1 CCS was replaced by the Mk 2. The Mk 2 was built by Raytheon. Mk 2 provides Tomahawk Block III vertical launch capability as well as fleet-requested improvements to Mk 48 ADCAP torpedo and Towed Array Target Motion Analysis (TMA) operability. The Mk 2 CCS paired with the AN/BQQ-5E system is referred to as the "QE-2" system. The CCS MK2 Block 1 A/B system architecture extends the CCS MK2 tactical system with a network of Tactical Advanced Computers (TAC-3). These TAC-3s are configured to support the SFMPL, NTCS-A, LINK-11 and ATWCS subsystems.

Sensors

Sonar

AN/BQQ-5

AN/BQQ-5 sensor suite consists of the AN/BQS-13 spherical sonar array and AN/UYK-44 computer. The AN/BQQ-5 was developed from the AN/BQQ-2 sonar system. The BQS 11, 12, and 13 spherical arrays have 1,241 transducers. Also equipped are a 104 hydrophone hull array and two towed arrays: the TB-12 (later replaced by the TB-16) and TB-23 or TB-29, of which there are multiple variants. There are 5 versions of the AN/BQQ-5 system, sequentially identified by letters A-E.

The 688i (Improved) subclass was initially equipped with the AN/BSY-1 SUBACS submarine advanced combat system that used an AN/BQQ-5E sensor system with updated computers and interface equipment. Development of the AN/BSY-1 and its sister the AN/BSY-2 for the Seawolf class was widely reported as one of the most problematic programs for the Navy, its cost and schedule suffering many setbacks.

A series of conformal passive hydrophones are hard-mounted to each side of the hull, using the AN/BQR-24 internal processor. The system uses FLIT (frequency line integration tracking) which homes in on precise narrowband frequencies of sound and, using the Doppler principle, can accurately provide firing solutions against very quiet submarines. The AN/BQQ-5's hull array doubled the performance of its predecessors.

AN/BQQ-10

The AN/BQQ-5 system was replaced by the AN/BQQ-10 system. Acoustic Rapid Commercial Off-The-Shelf Insertion (A-RCI), designated AN/BQQ-10, is a four-phase program for transforming existing submarine sonar systems (AN/BSY-1, AN/BQQ-5, and AN/BQQ-6) from legacy systems to a more capable and flexible COTS/Open System Architecture (OSA) and also provide the submarine force with a common sonar system. A single A-RCI Multi-Purpose Processor (MPP) has as much computing power as the entire Los Angeles (SSN-688/688I) submarine fleet combined and will allow the development and use of complex algorithms previously beyond the reach of legacy processors. The use of COTS/OSA technologies and systems will enable rapid periodic updates to both software and hardware. COTS-based processors will allow computer power growth at a rate commensurate with the commercial industry.[17]

Engineering and auxiliary systems

Two watertight compartments are used in the Los Angeles-class submarines. The forward compartment contains crew living spaces, weapons-handling spaces, and control spaces not critical to recovering propulsion. The aft compartment contains the bulk of the submarine's engineering systems, power generation turbines, and water-making equipment.[18] Some submarines in the class are capable of delivering Navy SEALs through either a SEAL Delivery Vehicle deployed from the Dry Deck Shelter or the Advanced SEAL Delivery System mounted on the dorsal side, although the latter was canceled in 2006 and removed from service in 2009.[19] A variety of atmospheric control devices are used to allow the vessel to remain submerged for long periods of time without ventilating, including an electrolytic oxygen generator, which produces oxygen for the crew and hydrogen as a byproduct. The hydrogen is pumped overboard but there is always a risk of fire or explosion from this process.[1][20]

.jpg)

While on the surface or at snorkel depth, the submarine may use the submarine's auxiliary or emergency diesel generator for power or ventilation[21][22] (e.g., following a fire).[23] The diesel engine in a 688 class can be quickly started by compressed air during emergencies or to evacuate noxious (nonvolatile) gases from the boat, although 'ventilation' requires raising a snorkel mast. During nonemergency situations, design constraints call for operators to allow the engine to reach normal operating temperatures before it is capable of producing full power, a process that may take from 20 to 30 minutes. However, the diesel generator can be immediately loaded to 100% power output, despite design criteria cautions, at the discretion of the submarine commander on the recommendation of the submarine's engineer, if necessity dictates such actions to: (a) restore electrical power to the submarine, (b) prevent a reactor incident from occurring or escalating, or (c) to protect the lives of the crew or others as determined necessary by the commanding officer.[24]

Normally, steam power is generated by the submarine's nuclear reactor delivering pressurized hot water to the steam generator, which generates steam to drive the steam-driven turbines and generators. While the emergency diesel generator is starting up, power can be provided from the submarine's battery through the ship service motor generators.[25] Likewise, propulsion is normally delivered through the submarine's steam-driven main turbines that drive the submarine's propeller through a reduction gear system. The submarine has no main drive shaft, unlike conventional diesel electric submarines.[26]

Propulsion

The ship is equipped with a light water reactor, model GE PWR S6G, generating 35,000 shaft horsepower (26,000 kW), developed and supplied by General Electric. The auxiliary prop motor by Magnatek supplies 242 kW. The life of the fuel cells is approximately ten years.[27] Part of the improved 688 program included the improved Performance Machinery Program Phase I.

The S6G reactor plant was originally designed to use the D1G-2 core, similar to the D2G reactor used on the Bainbridge-class guided missile cruiser. All Los Angeles-class submarines from USS Providence on were built with a D2W core. The D1G-2 cores are being replaced with D2W cores when the boats are refueled.

In popular culture

- Los Angeles-class submarines have been featured prominently in numerous Tom Clancy literary works and film adaptations, most notably USS Dallas in The Hunt for Red October.[28] Other appearances include USS Chicago in the novel Red Storm Rising and USS Cheyenne in SSN. In addition to fictional works, Clancy's 1993 non-fiction book Submarine: A Guided Tour Inside a Nuclear Warship features an in-depth exploration of USS Miami.

- USS Alexandria was used in the 2008 made-for-television film Stargate: Continuum.[29]

- 688 Attack Sub, a 1989 MS-DOS submarine simulator, allowed the player to control a Los Angeles-class submarine during a set of Cold War missions.

- Jane's 688(i) Hunter/Killer, Sub Command, and Dangerous Waters developed by Sonalysts Inc. are video games where players control the 688i Los Angeles-class submarine.

See also

- List of Los Angeles-class submarines

- List of active Los Angeles-class submarines by homeport

- List of submarine classes of the United States Navy

- List of submarines of the United States Navy

- List of submarine classes in service

- Submarines in the United States Navy

- Cruise missile submarine

- Attack submarine

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 SSN-688 Los Angeles class Archived 13 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. from Federation of American Scientists retrieved 29 February 2008 :The 18 SSN-688 class submarines that will be refueled in their midlives could make good candidates for a service life extension because they could operate for nearly 30 years after the refueling. After these submarines serve for 30 years, they could undergo a two-year overhaul and serve for one more 10-year operating cycle, for a total service life of 42 years.

- ↑ Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved January 5, 2018. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- ↑ "U.S. Navy Fact Sheet – Attack Submarines – SSN". United States Navy. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

General Characteristics, Los Angeles class ... Speed: 20+ knots (23+ miles per hour, 36.8 +km/h)

- 1 2 Polmar, Norman; Moore, Kenneth J. (2003). Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. Brassey's. p. 271. ISBN 1-57488-594-4.

- ↑ "Officials: U.S. submarine hit undersea mountain". CNN. 11 January 2005. Archived from the original on 18 October 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

The submarine was traveling in excess of 33 knots—about 35 mph—when its nose hit the undersea formation head-on, officials said.

- 1 2 Polmar, Norman "The U. S. Navy Electronic Warfare (Part 1)" United States Naval Institute Proceedings October 1979 p.137

- ↑ Farley, Robert (18 October 2014). "The Five Best Submarines of All Time". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014.

- ↑ Tyler, Patrick (1986). Running Critical. New York: Harper and Row. pp. 24, 56, 66–67. ISBN 978-0-06-091441-7.

- ↑ Waddle, Scott (2003). The Right Thing. Integrity Publishers. pp. xi (map/diagram). ISBN 1-59145-036-5.

This reference is for operating depth only

- ↑ Tyler, (1986). pp. 66–67, 156

- ↑ "Notes in pp. 64–67: Deliberations of ad-hoc committee on SSN 688 design taken from confidential sources and from interviews with Admiral [Ret] Rickover. ..." From Tyler, p. 365

- ↑ Saunders, (2004). pp. 838

- ↑ U.S. Submarines Since 1945: An Illustrated Design History. p. 118.

- ↑ http://andreasviklund.com, Lowell A. Benson, based on a design by Andreas Viklund -. "Systems, Navy Chapter". vipclubmn.org. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012.

- ↑ Friednam, Norman (1997). The Naval Institute Guide to World Naval Weapons Systems, 1997–1998. Naval Institute Press. p. 152. ISBN 9781557502681.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ SSN-688 Los Angeles Class Design. Los Angeles Class Archived 15 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. at Globalsecurity.org. Accessed on 7 January 2009

- ↑ Polmar & Moore, (2003). pp. 263

- ↑ Treadwell Supplies Oxygen Generator Components for Nuclear Subs Defense Industry Daily Archived 16 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. 28-January-2008

- ↑ Fairbanks Morse Engines Marine Installations Archived 26 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed on 29 April 2008

- ↑ Auxiliary Division on USS Cheyenne USS CHEYENNE SSN-773 Department & Divisions Archived 9 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. from Federation of American Scientists. Accessed on 29 April 2008

- ↑ Firefighting and Damage Control Update 181044Z JUN 98 (SUBS) Message Archived 14 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. COMSUBLANT (1998) Accessed on 29 April 2008

- ↑ DiMercurio, Michael; Benson, Michael (2003). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Submarines. New York, NY: Alpha Books. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-0-02-864471-4.

- ↑ Elger, Wallace (October 2005). "Development of Metal Fiber Electrical Brushes for 500kW SSMG Sets". Naval Engineers Journal. 117 (4): 37–38. doi:10.1111/j.1559-3584.2005.tb00382.x.

- ↑ Nuclear Propulsion Pressurized water Naval nuclear propulsion system Archived 26 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine. at Federation of American Scientists Accessed on 30 April 2008

- ↑ Clancy, Tom (1984). The Hunt for Red October. Naval Institute Press. pp. 71, 77, 81. ISBN 0-87021-285-0.

- ↑ "Stargate: Continuum to Film Scenes in the Arctic". comingsoon.net. 14 March 2007. Archived from the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

References

- This article includes information collected from the Naval Vessel Register, which, as a U.S. government publication, is in the public domain.

- Clancy, T. (1984). The Hunt for Red October. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-285-0.

- DiMercurio, M.; Benson, M (2003). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Submarines. New York: Alpha Books. ISBN 978-0-02-864471-4.

- Hutchinson, R (2001). Jane's Submarines: War Beneath the Waves from 1776 to the Present Say. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-710558-8.

- Polmar, N; Moore, K. J. (2003). Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. Washington, D.C.: Brassey's. ISBN 1-57488-594-4.

- Tyler, P. (1986). Running Critical. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-091441-7.

- Waddle, S (2003). The Right Thing. Nashville, Tennessee: Integrity Publishers. ISBN 1-59145-036-5.

- Saunders, S (2004). Jane's Fighting Ships, 2004-2005. Coulsdon, Surrey, UK: Jane's Information Group Limited. ISBN 0-7106-2623-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Los Angeles class submarines. |