Winter War

| Winter War |

|---|

| Articles |

| Related topics |

The Winter War[F 7] was a military conflict between the Soviet Union (USSR) and Finland. It began with a Soviet invasion of Finland on 30 November 1939, three months after the outbreak of World War II, and ended three and a half months later with the Moscow Peace Treaty on 13 March 1940. The League of Nations deemed the attack illegal and expelled the Soviet Union from the organisation.

The conflict began after the Soviets sought to obtain some Finnish territory, demanding among other concessions that Finland cede substantial border territories in exchange for land elsewhere, claiming security reasons—primarily the protection of Leningrad, 32 km (20 mi) from the Finnish border. Finland refused, and the USSR invaded the country. Many sources conclude that the Soviet Union had intended to conquer all Finland, and use the establishment of the puppet Finnish Communist government and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact's secret protocols as evidence of this,[F 8] while other sources argue against the idea of the full Soviet conquest.[F 9] Finland repelled Soviet attacks for more than two months and inflicted substantial losses on the invaders while temperatures ranged as low as −43 °C (−45 °F). After the Soviet military reorganised and adopted different tactics, they renewed their offensive in February and overcame Finnish defenses.

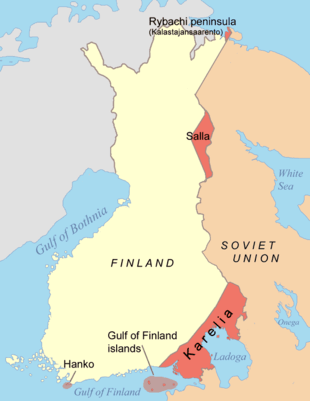

Hostilities ceased in March 1940 with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty. Finland ceded 11 percent of its territory representing 30 percent of its economy to the Soviet Union. Soviet losses were heavy, and the country's international reputation suffered. Soviet gains exceeded their pre-war demands and the USSR received substantial territory along Lake Ladoga and in Northern Finland. Finland retained its sovereignty and enhanced its international reputation. The poor performance of the Red Army encouraged Adolf Hitler to think that an attack on the Soviet Union would be successful and confirmed negative Western opinions of the Soviet military. After 15 months of Interim Peace, in June 1941, Nazi Germany commenced Operation Barbarossa and the Continuation War between Finland and the USSR began.

Background

Soviet–Finnish relations and politics

Until the beginning of the 19th century, Finland constituted the eastern part of the Kingdom of Sweden. In 1809, to protect its imperial capital, Saint Petersburg, the Russian Empire conquered Finland and converted it into an autonomous buffer state.[41] The resulting Grand Duchy of Finland enjoyed wide autonomy within the Empire until the end of the 19th century, when Russia began attempts to assimilate Finland as part of a general policy to strengthen the central government and unify the Empire through russification. These attempts were aborted because of Russia's internal strife, but they ruined Russia's relations with the Finns and increased support for Finnish self-determination movements.[42]

World War I led to the collapse of the Russian Empire during the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Russian Civil War of 1917–1920, giving Finland a window of opportunity; on 6 December 1917, the Senate of Finland declared the nation's independence. The new Bolshevik Russian government was fragile, and civil war had broken out in Russia in November 1917; the Bolsheviks determined they could not hold onto peripheral parts of the old empire. Thus, Soviet Russia (later the USSR) recognised the new Finnish government just three weeks after the declaration.[42] Finland achieved full sovereignty in May 1918 after a 4-month civil war, with the conservative Whites winning over the socialist Reds, and the expulsion of Bolshevik troops.[43]

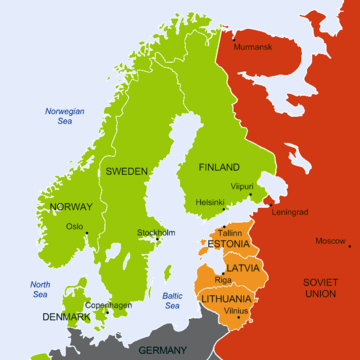

Finland joined the League of Nations in 1920, from which it sought security guarantees, but Finland's primary goal was cooperation with the Scandinavian countries. The Finnish and Swedish militaries engaged in wide-ranging cooperation, but focused on the exchange of information and on defence planning for the Åland Islands rather than on military exercises or on stockpiling and deployment of materiel. Nevertheless, the government of Sweden carefully avoided committing itself to Finnish foreign policy.[44] Finland's military policy included clandestine defence cooperation with Estonia.[45]

The period after the Finnish Civil War till the early 1930s proved a politically unstable time in Finland due to the continued rivalry between the conservative and socialist parties. The Communist Party of Finland was declared illegal in 1931, and the nationalist Lapua Movement organised anti-communist violence, which culminated in a failed coup attempt in 1932. The successor of the Lapua Movement, the Patriotic People's Movement, only had a minor presence in national politics with at most 14 seats out of 200 in the Finnish parliament.[46] By the late 1930s, the export-oriented Finnish economy was growing and the nation's extreme political movements had diminished.[47]

After Soviet involvement in the Finnish Civil War in 1918, no formal peace treaty was signed. In 1918 and 1919, Finnish volunteers conducted two unsuccessful military incursions across the Soviet border, the Viena and Aunus expeditions, to annex Karelian areas according to the Greater Finland ideology of combining all Finnic peoples into a single state. In 1920, Finnish communists based in the USSR attempted to assassinate the former Finnish White Guard Commander-in-Chief, Marshal Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim. On 14 October 1920, Finland and Soviet Russia signed the Treaty of Tartu, confirming the old border between the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland and Imperial Russia proper as the new Finnish–Soviet border. Finland also received Petsamo, with its ice-free harbour on the Arctic Ocean.[48][49] Despite the signing of the treaty, relations between the two countries remained strained. The Finnish government allowed volunteers to cross the border to support the East Karelian uprising in Russia in 1921, and Finnish communists in the Soviet Union continued to prepare for a revanche and staged a cross-border raid into Finland, called the Pork mutiny, in 1922.[50] In 1932, the USSR and Finland signed a non-aggression pact, which was reaffirmed for a ten-year period in 1934.[50] While foreign trade in Finland was booming, less than one percent of Finnish trade was with the Soviet Union.[51] In 1934, the Soviet Union joined the League of Nations.[50]

Joseph Stalin regarded it a disappointment that the Soviet Union could not halt the Finnish revolution.[52] He thought that the pro-Finland movement in Karelia posed a direct threat to Leningrad and that the area and defences of Finland could be used to invade the Soviet Union or restrict fleet movements.[53] During Stalin's rule, Soviet propaganda painted Finland's leadership as a "vicious and reactionary fascist clique". Field Marshal Mannerheim and Väinö Tanner, the leader of the Finnish Social Democratic Party, were targeted for particular scorn.[54] When Stalin gained absolute power through the Great Purge of 1938, the USSR changed its foreign policy toward Finland and began pursuing the reconquest of the provinces of Tsarist Russia lost during the chaos of the October Revolution and the Russian Civil War almost two decades earlier. The Soviet leadership believed that the old empire possessed the ideal amount of territorial security, and wanted the newly christened city of Leningrad, only 32 km (20 mi) from the Finnish border, to enjoy a similar level of security against the rising power of Nazi Germany.[55][56] In essence, the border between the Grand Duchy of Finland and Russia proper was never supposed to become international.[57][58]

Negotiations

In April 1938, NKVD agent Boris Yartsev contacted the Finnish Foreign Minister Rudolf Holsti and Prime Minister Aimo Cajander, stating that the Soviet Union did not trust Germany and that war was considered possible between the two countries. The Red Army would not wait passively behind the border but would rather "advance to meet the enemy". Finnish representatives assured Yartsev that Finland was committed to a policy of neutrality and that the country would resist any armed incursion. Yartsev suggested that Finland cede or lease some islands in the Gulf of Finland along the seaward approaches to Leningrad; Finland refused.[59][60]

Negotiations continued throughout 1938 without results. Finnish reception of Soviet entreaties was decidedly cool, as the violent collectivisation and purges in Stalin's Soviet Union resulted in a poor opinion of the country. Most of the Finnish communist elite in the Soviet Union had been executed during the Great Purge, further tarnishing the USSR's image in Finland. At the same time, Finland was attempting to negotiate a military cooperation plan with Sweden and hoping to jointly defend the Åland Islands.[61]

The Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939. The pact was nominally a non-aggression treaty, but it included a secret protocol in which Eastern European countries were divided into spheres of interest. Finland fell into the Soviet sphere. On 1 September 1939, Germany began its invasion of Poland and two days later Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. On 17 September, the Soviet Union invaded Eastern Poland. The Baltic states were soon forced to accept treaties allowing the USSR to establish military bases and to station troops on their soil.[62] The government of Estonia accepted the ultimatum, signing the agreement in September. Latvia and Lithuania followed in October. Unlike the Baltic states, Finland started a gradual mobilisation under the guise of "additional refresher training."[63] The Soviets had already started intensive mobilisation near the Finnish border in 1938–39. Assault troops thought necessary for the invasion did not begin deployment until October 1939. Operational plans made in September called for the invasion to start in November.[64][65]

On 5 October 1939, the Soviet Union invited a Finnish delegation to Moscow for negotiations. J.K. Paasikivi, the Finnish envoy to Sweden, was sent to Moscow to represent the Finnish government.[63] The Soviet delegation demanded that the border between the USSR and Finland on the Karelian Isthmus be moved westward to a point only 30 km (19 mi) east of Vyborg (Finnish: Viipuri) and that Finland destroy all existing fortifications on the Karelian Isthmus. Likewise, the delegation demanded the cession of islands in the Gulf of Finland as well as Rybachy Peninsula (Finnish: Kalastajasaarento). The Finns would have to lease the Hanko Peninsula for thirty years and permit the Soviets to establish a military base there. In exchange, the Soviet Union would cede Repola and Porajärvi municipalities from Eastern Karelia, an area twice the size of the territory demanded from Finland.[63][66]

The Soviet offer divided the Finnish government, but was eventually rejected with respect to the opinion of the public and Parliament. On 31 October, Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov announced Soviet demands in public in the Supreme Soviet. The Finns made two counteroffers whereby Finland would cede the Terijoki area to the Soviet Union, which would double the distance between Leningrad and the Finnish border, far less than the Soviets had demanded,[67] as well as the islands in the Gulf of Finland.[68]

Shelling of Mainila and Soviet intentions

On 26 November 1939, an incident was reported near the Soviet village of Mainila, close to the border with Finland. A Soviet border guard post had been shelled by an unknown party resulting, according to Soviet reports, in the deaths of four and injuries of nine border guards. Research conducted by several Finnish and Russian historians later concluded that the shelling was a false flag operation carried out from the Soviet side of the border by an NKVD unit with the purpose of providing the Soviet Union with a casus belli and a pretext to withdraw from the non-aggression pact.[69][F 10]

Molotov claimed that the incident was a Finnish artillery attack and demanded that Finland apologise for the incident and move its forces beyond a line 20–25 km (12–16 mi) away from the border.[72] Finland denied responsibility for the attack, rejected the demands and called for a joint Finnish–Soviet commission to examine the incident. In turn, the Soviet Union claimed that the Finnish response was hostile, renounced the non-aggression pact and severed diplomatic relations with Finland on 28 November. In the following years, Soviet historiography described the incident as Finnish provocation. Doubt on the official Soviet version was cast only in the late 1980s, during the policy of glasnost. The issue continued to divide Russian historiography even after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.[73][74]

In 2013, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated at a meeting with military historians that the USSR launched the Winter War to "correct mistakes" made in determining the border with Finland after 1917.[75] Opinion on the scale of the initial Soviet invasion decision is divided: some sources conclude that the Soviet Union had intended to conquer Finland in full, and cite the establishment of the puppet Finnish Communist government and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact's secret protocols as proof of their conclusions.[F 11] Hungarian historian István Ravasz wrote that the Central Committee had set out in 1939 that the former borders of the Tsarist Empire were to be restored—including Finland.[33] American political scientist Dan Reiter stated that the USSR "sought to impose a regime change" and thus "achieve absolute victory". He quotes Molotov, who commented in November 1939 on the regime-change plan to a Soviet ambassador that the new government "will not be Soviet, but one of a democratic republic. Nobody is going to set up Soviets over there, but we hope it will be a government we can come to terms with as to ensure the security of Leningrad."[36]

Others argue against the idea of a complete Soviet conquest. American historian William R. Trotter asserted that Stalin's objective was to secure Leningrad's flank from a possible German invasion through Finland. He stated that "the strongest argument" against a Soviet intention of full conquest is that it did not happen in either 1939 or during the Continuation War in 1944—even though Stalin "could have done so with comparative ease."[38] Bradley Lightbody wrote that the "entire Soviet aim had been to make the Soviet border more secure."[39] According to Russian historian A. Chubaryan in 2002, no documents had been found in Russian archives that support a Soviet plan to annex Finland. Rather, the objective was to gain Finnish territory and reinforce Soviet influence in the region.[37]

Opposing forces

Soviet military plan

Before the war, Soviet leadership expected total victory within a few weeks. The Red Army had just completed the invasion of Eastern Poland at a cost of fewer than 4,000 casualties after Germany attacked Poland from the west. Stalin's expectations of a quick Soviet triumph were backed up by politician Andrei Zhdanov and military strategist Kliment Voroshilov, but other generals were more reserved. The Chief of Staff of the Red Army Boris Shaposhnikov advocated a fuller build-up, extensive fire support and logistical preparations, and a rational order of battle, and the deployment of the army's best units. Zhdanov's military commander Kirill Meretskov reported that "The terrain of coming operations is split by lakes, rivers, swamps, and is almost entirely covered by forests [...] The proper use of our forces will be difficult." These doubts were not reflected in his troop deployments. Meretskov announced publicly that the Finnish campaign would take two weeks at the most. Soviet soldiers had even been warned not to cross the border into Sweden by mistake.[76]

Stalin's purges in the 1930s had devastated the officer corps of the Red Army; those purged included three of its five marshals, 220 of its 264 division or higher-level commanders, and 36,761 officers of all ranks. Fewer than half of all the officers remained.[77][78] They were commonly replaced by soldiers who were less competent but more loyal to their superiors. Unit commanders were overseen by political commissars, whose approval was needed to ratify military decisions and who evaluated those decisions based on their political merits. The dual system further complicated Soviet chain of command[79][80] and annulled the independence of commanding officers.[81]

After the Soviet success in the battles of Khalkhin Gol against Japan on the USSR's eastern border, Soviet high command had divided into two factions. One side was represented by Spanish Civil War veterans General Pavel Rychagov from the Soviet Air Force, tank expert General Dmitry Pavlov, and Stalin's favourite general, Marshal Grigory Kulik, chief of artillery.[82] The other was led by Khalkhin Gol veterans General Georgy Zhukov of the Red Army and General Grigory Kravchenko of the Soviet Air Force.[83] Under this divided command structure, the lessons of the Soviet Union's "first real war on a massive scale using tanks, artillery, and aircraft" at Khalkin Gol went unheeded.[84] As a result, Russian BT tanks were less successful during the Winter War, and it took the Soviet Union three months and over a million men to accomplish what Zhukov did at Khalkhin Gol in ten days.[84][85]

Soviet order of battle

Soviet generals were impressed by the success of German Blitzkrieg tactics. Blitzkrieg had been tailored to Central European conditions with a dense, well-mapped network of paved roads. Armies fighting in Central Europe had recognised supply and communications centres, which could be easily targeted by armoured vehicle regiments. Finnish Army centres, by contrast, were deep inside the country. There were no paved roads, and even gravel or dirt roads were scarce; most of the terrain consisted of trackless forests and swamps. War correspondent John Langdon-Davies observed the landscape as follows: "Every acre of its surface was created to be the despair of an attacking military force."[86] Waging Blitzkrieg in Finland was a highly difficult proposition, and according to Trotter, the Red Army failed to meet the level of tactical coordination and local initiative required to execute Blitzkrieg tactics in the Finnish theatre.[87]

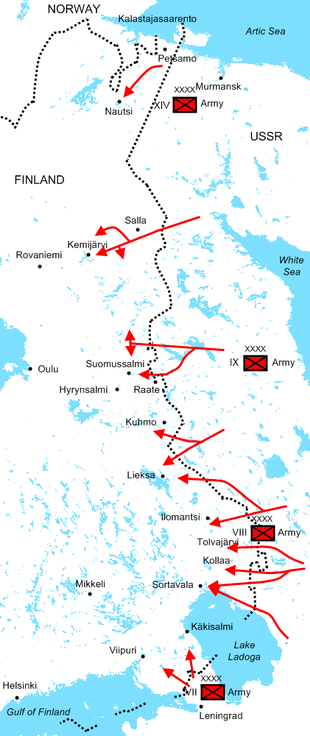

The Soviet forces were organised as follows:[88]

- The 7th Army, comprising nine divisions, a tank corps and three tank brigades, was located on the Karelian Isthmus. Its objective was the city of Vyborg. The force was later divided into the 7th and 13th Armies.[89]

- The 8th Army, comprising six divisions and a tank brigade, was located north of Lake Ladoga. Its mission was to execute a flanking manoeuvre around the northern shore of Lake Ladoga to strike at the rear of the Mannerheim Line.[89]

- The 9th Army was positioned to strike into Central Finland through the Kainuu region. It was composed of three divisions with one more on its way. Its mission was to thrust westward to cut Finland in half.[89]

- The 14th Army, comprising three divisions, was based in Murmansk. Its objective was to capture the Arctic port of Petsamo and then advance to the town of Rovaniemi.[89]

Finnish order of battle

The Finnish strategy was dictated by geography. The 1,340 km (830 mi)-long frontier with the Soviet Union was mostly impassable except along a handful of unpaved roads. In pre-war calculations, the Finnish Defence Command, which had established its wartime Headquarters at Mikkeli,[88] estimated seven Soviet divisions on the Karelian Isthmus and no more than five along the whole border north of Lake Ladoga. In the estimation, the manpower ratio would have favoured the attacker by three to one. The true ratio was much higher; for example, 12 Soviet divisions were deployed to the north of Lake Ladoga.[92]

An even greater problem than lack of soldiers was the lack of materiel; foreign shipments of anti-tank weapons and aircraft were arriving in small quantities. The ammunition situation was alarming, as stockpiles had cartridges, shells, and fuel only to last 19–60 days. The ammunition shortage meant the Finns could seldom afford counterbattery or saturation fire. Finnish tank forces were operationally non-existent.[92] The ammunition situation was alleviated somewhat since Finns were largely armed with Mosin–Nagant rifles dating from the Finnish Civil War, which used the same 7.62×54mmR cartridge used by Soviet forces. Some Finnish soldiers maintained their ammunition supply by looting the bodies of dead Soviet soldiers.[93]

The Finnish forces were positioned as follows:[94]

- The Army of the Isthmus was composed of six divisions under the command of Hugo Österman. The II Army Corps was positioned on its right flank and the III Army Corps, on its left flank.

- The IV Army Corps was located north of Lake Ladoga. It was composed of two divisions under Juho Heiskanen, who was soon replaced by Woldemar Hägglund.

- The North Finland Group was a collection of White Guards, border guards and drafted reservist units under Wiljo Tuompo.

Soviet invasion

Start of the invasion and political operations

On 30 November 1939, Soviet forces invaded Finland with 21 divisions, totalling 450,000 men, and bombed Helsinki,[89][95] inflicting substantial damage and casualties. In response to international criticism, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov stated that the Soviet Air Force was not bombing Finnish cities, but rather dropping humanitarian aid to the starving Finnish population, sarcastically dubbed Molotov bread baskets by Finns.[96][97] The Finnish statesman J. K. Paasikivi commented that the Soviet attack without a declaration of war violated three separate non-aggression pacts: the Treaty of Tartu signed in 1920, the non-aggression pact between Finland and the Soviet Union signed in 1932 and again in 1934, and also the Covenant of the League of Nations, which the Soviet Union signed in 1934.[71] Field Marshal C.G.E. Mannerheim was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Defence Forces after the Soviet attack. In a further reshuffling, Aimo Cajander's caretaker cabinet was replaced by Risto Ryti and his cabinet, with Väinö Tanner as foreign minister, due to opposition to Cajander's pre-war politics.[98] Finland brought the matter of the Soviet invasion before the League of Nations. The League expelled the USSR on 14 December 1939 and exhorted its members to aid Finland.[99][100]

On 1 December 1939, the Soviet Union formed a puppet government, called the Finnish Democratic Republic and headed by Otto Wille Kuusinen, in the parts of Finnish Karelia occupied by the Soviets. Kuusinen's government was also referred to as the "Terijoki Government," after the village of Terijoki, the first settlement captured by the advancing Red Army.[101] After the war, the puppet government was disbanded. From the very outset of the war, working-class Finns stood behind the legitimate government in Helsinki.[99] Finnish national unity against the Soviet invasion was later called the spirit of the Winter War.[102]

First battles and Soviet advance to the Mannerheim Line

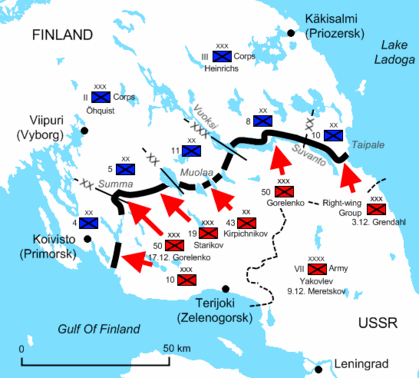

The Mannerheim Line, an array of Finnish defence structures, was located on the Karelian Isthmus approximately 30 to 75 km (19 to 47 mi) from the Soviet border. The Red Army soldiers on the Isthmus numbered 250,000, facing 130,000 Finns.[103] The Finnish command deployed a defence in depth of about 21,000 men in the area in front of the Mannerheim Line to delay and damage the Red Army before it reached the line.[104] In combat, the most severe cause of confusion among Finnish soldiers was Soviet tanks. The Finns had few anti-tank weapons and insufficient training in modern anti-tank tactics. According to Trotter, the favoured Soviet armoured tactic was a simple frontal charge, the weaknesses of which could be exploited. The Finns learned that at close range, tanks could be dealt with in many ways; for example, logs and crowbars jammed into the bogie wheels would often immobilise a tank. Soon, Finns fielded a better ad hoc weapon, the Molotov cocktail, a glass bottle filled with flammable liquids and with a simple hand-lit fuse. Molotov cocktails were eventually mass-produced by the Finnish Alko alcoholic beverage corporation and bundled with matches with which to light them. 80 Soviet tanks were destroyed in the border zone engagements.[105]

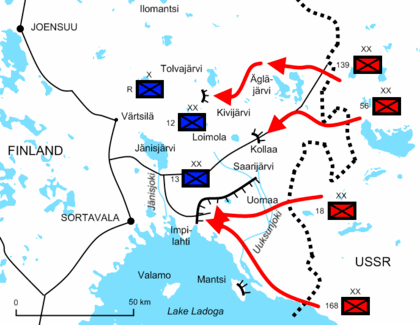

By 6 December, all of the Finnish covering forces had withdrawn to the Mannerheim Line. The Red Army began its first major attack against the Line in Taipale—the area between the shore of Lake Ladoga, the Taipale river and the Suvanto waterway. Along the Suvanto sector, the Finns had a slight advantage of elevation and dry ground to dig into. The Finnish artillery had scouted the area and made fire plans in advance, anticipating a Soviet assault. The Battle of Taipale began with a forty-hour Soviet artillery preparation. After the barrage, Soviet infantry attacked across open ground but was repulsed with heavy casualties. From 6 December to 12 December, the Red Army continued to try to engage using only one division. Next, the Red Army strengthened its artillery and deployed tanks and the 150th Rifle Division forward to the Taipale front. On 14 December, the bolstered Soviet forces launched a new attack but were pushed back again. A third Soviet division entered the fight but performed poorly and panicked under shell fire. The assaults continued without success, and the Red Army suffered heavy losses. One typical Soviet attack during the battle lasted just an hour but left 1,000 dead and 27 tanks strewn on the ice.[106] North of Lake Ladoga on the Ladoga Karelia front, the defending Finnish units relied on the terrain. Ladoga Karelia, a large forest wilderness, did not have road networks for the modern Red Army.[107] The Soviet 8th Army had extended a new railroad line to the border, which could double the supply capability on the front. On 12 December, the advancing Soviet 139th Rifle Division, supported by the 56th Rifle Division, was defeated by a much smaller Finnish force under Paavo Talvela in Tolvajärvi, the first Finnish victory of the war.[108]

In Central and Northern Finland, roads were few and the terrain hostile. The Finns did not expect large-scale Soviet attacks, but the Soviets sent eight divisions, heavily supported by armour and artillery. The 155th Rifle Division attacked at Lieksa, and further north the 44th attacked at Kuhmo. The 163rd Rifle Division was deployed at Suomussalmi and ordered to cut Finland in half by advancing on the Raate road. In Finnish Lapland, the Soviet 88th and 122nd Rifle Divisions attacked at Salla. The Arctic port of Petsamo was attacked by the 104th Mountain Rifle Division by sea and land, supported by naval gunfire.[109]

Operations from December to January

Weather conditions

The winter of 1939–40 was exceptionally cold with the Karelian Isthmus experiencing a record low temperature of −43 °C (−45 °F) on 16 January 1940.[110] At the beginning of the war, only those Finnish soldiers who were in active service had uniforms and weapons. The rest had to make do with their own clothing, which for many soldiers was their normal winter clothing with a semblance of insignia added. Finnish soldiers were skilled in cross-country skiing.[111] The cold, snow, forest, and long hours of darkness were factors that the Finns could use to their advantage. The Finns dressed in layers, and the ski troopers wore a lightweight white snow cape. This snow-camouflage made the ski troopers almost invisible as the Finns executed guerrilla attacks against Soviet columns. At the beginning of the war, Soviet tanks were painted in standard olive drab and men dressed in regular khaki uniforms. Not until late January 1940 did the Soviets paint their equipment white and issue snowsuits to their infantry.[112]

Most Soviet soldiers had proper winter clothes, but this was not the case with every unit. In the battle of Suomussalmi, thousands of Soviet soldiers died of frostbite. The Soviet troops also lacked skill in skiing, so soldiers were restricted to movement by road and were forced to move in long columns. The Red Army lacked proper winter tents, and troops had to sleep in improvised shelters.[113] Some Soviet units incurred frostbite casualties as high as ten percent even before crossing the Finnish border.[112] The cold weather did confer an advantage to Soviet tanks, as they could move over frozen terrain and bodies of water, rather than being immobilised in swamps and mud.[113] According to Krivosheev, at least 61,506 Soviet troops were sick or frostbitten during the war.[22]

Finnish guerrilla tactics

In battles from Ladoga Karelia to the Arctic port of Petsamo, the Finns used guerrilla tactics. The Red Army was superior in numbers and materiel, but Finns used the advantages of speed, manoeuvre warfare and economy of force. Particularly on the Ladoga Karelia front and during the battle of Raate road, the Finns isolated smaller portions of numerically superior Soviet forces. With Soviet forces divided into smaller groups, the Finns dealt with them individually and attacked from all sides.[114]

For many of the encircled Soviet troops in a pocket (called a motti in Finnish, originally meaning 1 m3 (35 cu ft) of firewood), staying alive was an ordeal comparable to combat. The men were freezing and starving and endured poor sanitary conditions. Historian William R. Trotter described these conditions as follows: "The Soviet soldier had no choice. If he refused to fight, he would be shot. If he tried to sneak through the forest, he would freeze to death. And surrender was no option for him; Soviet propaganda had told him how the Finns would torture prisoners to death."[115]

Battles of the Mannerheim Line

The terrain on the Karelian Isthmus did not allow guerrilla tactics, so the Finns were forced to resort to the more conventional Mannerheim Line, with its flanks protected by large bodies of water. Soviet propaganda claimed that it was as strong as or even stronger than the Maginot Line. Finnish historians, for their part, have belittled the line's strength, insisting that it was mostly conventional trenches and log-covered dugouts.[116] The Finns had built 221 strong-points along the Karelian Isthmus, mostly in the early 1920s. Many were extended in the late 1930s. Despite these defensive preparations, even the most fortified section of the Mannerheim Line had only one reinforced-concrete bunker per kilometre. Overall, the line was weaker than similar lines in mainland Europe.[117] According to the Finns, the real strength of the line was the "stubborn defenders with a lot of sisu" – a Finnish idiom roughly translated as "guts, fighting spirit."[116]

On the eastern side of the Isthmus, the Red Army attempted to break through the Mannerheim Line at the battle of Taipale. On the western side, Soviet units faced the Finnish line at Summa, near the city of Vyborg, on 16 December. The Finns had built 41 reinforced-concrete bunkers in the Summa area, making the defensive line in this area stronger than anywhere else on the Karelian Isthmus. Because of a mistake in planning, the nearby Munasuo swamp had a 1 km (0.62 mi)-wide gap in the line.[118] During the first battle of Summa, a number of Soviet tanks broke through the thin line on 19 December, but the Soviets could not benefit from the situation because of insufficient cooperation between branches of service. The Finns remained in their trenches, allowing the Soviet tanks to move freely behind the Finnish line, as the Finns had no proper anti-tank weapons. The Finns succeeded in repelling the main Soviet assault. The tanks, stranded behind enemy lines, attacked the strongpoints at random until they were eventually destroyed, 20 in all. By 22 December, the battle ended in a Finnish victory.[119]

The Soviet advance was stopped at the Mannerheim Line. Red Army troops suffered from poor morale and a shortage of supplies, eventually refusing to participate in more suicidal frontal attacks. The Finns, led by General Harald Öhquist, decided to launch a counterattack and encircle three Soviet divisions into a motti near Vyborg on 23 December. Öhquist's plan was bold, and it failed. The Finns lost 1,300 men, and the Soviets were later estimated to have lost a similar number.[120]

Battles in Ladoga Karelia

The strength of the Red Army north of Lake Ladoga in Ladoga Karelia surprised the Finnish Headquarters. Two Finnish divisions were deployed there, the 12th Division led by Lauri Tiainen and the 13th Division led by Hannu Hannuksela. They also had a support group of three brigades, bringing their total strength to over 30,000. The Soviets deployed a division for almost every road leading west to the Finnish border. The 8th Army was led by Ivan Khabarov, who was replaced by Grigori Shtern on 13 December.[122] The Soviets' mission was to destroy the Finnish troops in the area of Ladoga Karelia and advance into the area between Sortavala and Joensuu within 10 days. The Soviets had a 3:1 advantage in manpower and a 5:1 advantage in artillery, as well as air supremacy.[123]

Finnish forces panicked and retreated in front of the overwhelming Red Army. The commander of the Finnish IV Army Corps Juho Heiskanen was replaced by Woldemar Hägglund on 4 December.[124] On 7 December, in the middle of the Ladoga Karelian front, Finnish units retreated near the small stream of Kollaa. The waterway itself did not offer protection, but alongside it, there were ridges up to 10 m (33 ft) high. The ensuing battle of Kollaa lasted until the end of the war. A memorable quote, "Kollaa holds" (Finnish: Kollaa kestää) became a legendary motto among Finns.[125] Further contributing to the legend of Kollaa was the sniper Simo Häyhä, dubbed "the White Death" by Soviets, and credited with over 250 kills. To the north, the Finns retreated from Ägläjärvi to Tolvajärvi on 5 December and then repelled a Soviet offensive in the battle of Tolvajärvi on 11 December.[126]

In the south, two Soviet divisions were united on the northern side of the Lake Ladoga coastal road. As before, these divisions were trapped as the more mobile Finnish units counterattacked from the north to flank the Soviet columns. On 19 December, the Finns temporarily ceased their assaults due to exhaustion.[127] It was not until the period of 6–16 January 1940 that the Finns resumed their offensive, dividing Soviet divisions into smaller mottis.[128] Contrary to Finnish expectations, the encircled Soviet divisions did not try to break through to the east but instead entrenched. They were expecting reinforcements and supplies to arrive by air. As the Finns lacked the necessary heavy artillery equipment and were short of men, they often did not directly attack the mottis they had created; instead, they worked to eliminate only the most dangerous threats. Often the motti tactic was not applied as a strategy, but as a Finnish adaptation to the behaviour of Soviet troops under fire.[129] In spite of the cold and hunger, the Soviet troops did not surrender easily but fought bravely, often entrenching their tanks to be used as pillboxes and building timber dugouts. Some specialist Finnish soldiers were called in to attack the mottis; the most famous of them was Major Matti Aarnio, or "Motti-Matti" as he became known.[130]

In Northern Karelia, Soviet forces were outmanoeuvred at Ilomantsi and Lieksa. The Finns used effective guerrilla tactics, taking special advantage of their superior skiing skills and snow-white layered clothing and executing surprise ambushes and raids. By the end of December, the Soviets decided to retreat and transfer resources to more critical fronts.[131]

Battles in Kainuu

The Suomussalmi–Raate engagement was a double operation[132] which would later be used by military academics as a classic example of what well-led troops and innovative tactics can do against a much larger adversary. Suomussalmi was a town of 4,000 with long lakes, wild forests and few roads. The Finnish command believed that the Soviets would not attack here, but the Red Army committed two divisions to the Kainuu area with orders to cross the wilderness, capture the city of Oulu and effectively cut Finland in two. There were two roads leading to Suomussalmi from the frontier: the northern Juntusranta road and the southern Raate road.[133]

The battle of Raate road, which occurred during the month-long battle of Suomussalmi, resulted in one of the largest Soviet losses in the Winter War. The Soviet 44th and parts of the 163rd Rifle Division, comprising about 14,000 troops,[134] were almost completely destroyed by a Finnish ambush as they marched along the forest road. A small unit blocked the Soviet advance while Finnish Colonel Hjalmar Siilasvuo and his 9th Division cut off the retreat route, split the enemy force into smaller mottis, and then proceeded to destroy the remnants in detail as they retreated. The Soviets suffered 7,000–9,000 casualties;[135] the Finnish units, 400.[136] The Finnish troops captured dozens of tanks, artillery pieces, anti-tank guns, hundreds of trucks, almost 2,000 horses, thousands of rifles, and much-needed ammunition and medical supplies.[137]

Battles in Finnish Lapland

In Finnish Lapland, the forests gradually thin until in the north there are no trees at all. Thus, the area offers more room for tank deployment, but it is sparsely populated and experiences copious snowfall. The Finns expected nothing more than raiding parties and reconnaissance patrols, but instead, the Soviets sent full divisions.[138] On 11 December, the Finns rearranged the defence of Lapland and detached the Lapland Group from the North Finland Group. The group was placed under the command of Kurt Wallenius.[139]

In Southern Lapland, near the village of Salla, the Soviet 88th and 122nd Divisions, totalling 35,000 men, advanced. In the battle of Salla, the Soviets proceeded easily to Salla, where the road forked. The northern branch moved toward Pelkosenniemi while the rest approached Kemijärvi. On 17 December, the Soviet northern group, comprising an infantry regiment, a battalion, and a company of tanks, was outflanked by a Finnish battalion. The 122nd retreated, abandoning much of its heavy equipment and vehicles. Following this success, the Finns shuttled reinforcements to the defensive line in front of Kemijärvi. The Soviets hammered the defensive line without success. The Finns counterattacked, and the Soviets retreated to a new defensive line where they stayed for the rest of the war.[140][141]

To the north was Finland's only ice-free port in the Arctic, Petsamo. The Finns lacked the manpower to defend it fully, as the main front was distant at the Karelian Isthmus. In the battle of Petsamo, the Soviet 104th Division attacked the Finnish 104th Independent Cover Company. The Finns abandoned Petsamo and concentrated on delaying actions. The area was treeless, windy, and relatively low, offering little defensible terrain. The almost constant darkness and extreme temperatures of the Lapland winter benefited the Finns, who executed guerrilla attacks against Soviet supply lines and patrols. As a result, the Soviet movements were halted by the efforts of one-fifth as many Finns.[138]

Aerial warfare

Soviet Air Force

The USSR enjoyed air superiority throughout the war. The Soviet Air Force, supporting the Red Army's invasion with about 2,500 aircraft (the most common type being Tupolev SB), was not as effective as the Soviets might have hoped. The material damage by the bomb raids was slight as Finland offered few valuable targets for strategic bombing. Often, targets were village depots with little value. The country had few modern highways in the interior, therefore making the railways the main targets for bombers. Rail tracks were cut thousands of times but the Finns hastily repaired them and service resumed within a matter of hours.[142] The Soviet Air Force learned from its early mistakes, and by late February instituted more effective tactics.[143]

The largest bombing raid against the capital of Finland, Helsinki, occurred on the first day of the war. The capital was bombed only a few times thereafter. All in all, Soviet bombings cost Finland five percent of its total man-hour production. Nevertheless, Soviet air attacks affected thousands of civilians, killing 957.[144] The Soviets recorded 2,075 bombing attacks in 516 localities. The city of Vyborg, a major Soviet objective close to the Karelian Isthmus front, was almost levelled by nearly 12,000 bombs.[145] No attacks on civilian targets were mentioned in Soviet radio or newspaper reports. In January 1940, the Soviet Pravda newspaper continued to stress that no civilian targets in Finland had been struck, even accidentally.[146] It is estimated that the Soviet air force lost about 400 aircraft because of inclement weather, lack of fuel and tools, and during transport to the front. The Soviet Air Force flew approximately 44,000 sorties during the war.[143]

Finnish Air Force

At the beginning of the war, Finland had a small air force, with only 114 combat planes fit for duty. Missions were limited, and fighter aircraft were mainly used to repel Soviet bombers. Strategic bombings doubled as opportunities for military reconnaissance. Old-fashioned and few in number, aircraft offered little support for Finnish ground troops. In spite of losses, the number of planes in the Finnish Air Force rose by over 50 percent by the end of the war.[147] The Finns received shipments of British, French, Italian, Swedish and American aircraft.[148]

Finnish fighter pilots often flew their motley collection of planes into Soviet formations that outnumbered them 10 or even 20 times. Finnish fighters shot down a confirmed 200 Soviet aircraft, while losing 62 of their own.[18] Finnish anti-aircraft guns downed more than 300 enemy aircraft.[18] Often, a Finnish forward air base consisted of a frozen lake, a windsock, a telephone set and some tents. Air-raid warnings were given by Finnish women organised by the Lotta Svärd.[149]

Naval warfare

Naval activity

There was little naval activity during the Winter War. The Baltic Sea began to freeze over by the end of December, impeding the movement of warships; by mid-winter, only ice breakers and submarines could still move. The other reason for low naval activity was the nature of Soviet Navy forces in the area. The Baltic Fleet was a coastal defence force which did not have the training, logistical structure, or landing craft to undertake large-scale operations. The Baltic Fleet possessed two battleships, one heavy cruiser, almost 20 destroyers, 50 motor torpedo boats, 52 submarines, and other miscellaneous vessels. The Soviets used naval bases in Paldiski, Tallinn and Liepāja for their operations.[150]

The Finnish Navy was a coastal defence force with two coastal defence ships, five submarines, four gunboats, seven motor torpedo boats, one minelayer and six minesweepers. The two coastal defence ships, Ilmarinen and Väinämöinen, were moved to harbour in Turku where they were used to bolster the air defence. Their anti-aircraft guns shot down one or two planes over the city, and the ships remained there for the rest of the war.[98] As well as coastal defence, the Finnish Navy protected the Åland islands and Finnish merchant vessels in the Baltic Sea.[151]

Soviet aircraft bombed Finnish vessels and harbours and dropped mines into Finnish seaways. Still, only five merchant ships were lost to Soviet action. World War II, which had started before the Winter War, proved more costly for the Finnish merchant vessels, with 26 lost due to hostile action in 1939 and 1940.[152]

Coastal artillery

Finnish coastal artillery batteries defended important harbours and naval bases. Most batteries were left over from the Imperial Russian period, with 152 mm (6.0 in) guns being the most numerous. Finland attempted to modernise its old guns and installed a number of new batteries, the largest of which featured a 305 mm (12.0 in) gun battery originally intended to block the Gulf of Finland to Soviet ships with the help of batteries on the Estonian side.[153]

The first naval battle occurred in the Gulf of Finland on 1 December, near the island of Russarö, 5 km (3.1 mi) south of Hanko. That day, the weather was fair and visibility, excellent. The Finns spotted the Soviet cruiser Kirov and two destroyers. When the ships were at a range of 24 km (13 nmi; 15 mi), the Finns opened fire with four 234 mm (9.2 in) coastal guns. After five minutes of firing by the coastal guns, the cruiser had been damaged by near misses and retreated. The destroyers remained undamaged, but the Kirov suffered 17 dead and 30 wounded. The Soviets already knew the locations of the Finnish coastal batteries, but were surprised by their range.[154]

Coastal artillery had a greater effect on land by reinforcing defence in conjunction with army artillery. Two sets of fortress artillery made significant contributions to the early battles on the Karelian Isthmus and in Ladoga Karelia. These were located at Kaarnajoki on the Eastern Isthmus and at Mantsi on the northeastern shore of Lake Ladoga. The fortress of Koivisto provided similar support from the southwestern coast of the Isthmus.[155]

Soviet breakthrough in February

Red Army reforms and offensive preparations

Joseph Stalin was not pleased with the results of December in the Finnish campaign. The Red Army had been humiliated. By the third week of the war, Soviet propaganda was working hard to explain the failures of the Soviet military to the populace: blaming bad terrain and harsh climate, and falsely claiming that the Mannerheim Line was stronger than the Maginot Line, and that the Americans had sent 1,000 of their best pilots to Finland. Chief of Staff Boris Shaposhnikov was given full authority over operations in the Finnish theatre, and he ordered the suspension of frontal assaults in late December. Kliment Voroshilov was replaced with Semyon Timoshenko as the commander of the Soviet forces in the war on 7 January.[156]

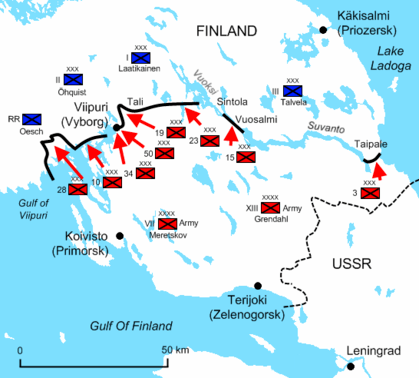

The main focus of the Soviet attack was switched to the Karelian Isthmus. Timoshenko and Zhdanov reorganised and tightened control between different branches of service in the Red Army. They also changed tactical doctrines to meet the realities of the situation. All Soviet forces on the Karelian Isthmus were divided into two armies: the 7th and the 13th Army. The 7th Army, now under Kirill Meretskov, would concentrate 75 percent of its strength against the 16 km (9.9 mi) stretch of the Mannerheim Line between Taipale and the Munasuo swamp. Tactics would be basic: an armoured wedge for the initial breakthrough, followed by the main infantry and vehicle assault force. The Red Army would prepare by pinpointing the Finnish frontline fortifications. The 123rd Rifle Division then rehearsed the assault on life-size mock-ups. The Soviets shipped large numbers of new tanks and artillery pieces to the theatre. Troops were increased from ten divisions to 25–26 divisions with six or seven tank brigades and several independent tank platoons as support, totalling 600,000 soldiers.[157] On 1 February, the Red Army began a large offensive, firing 300,000 shells into the Finnish line in the first 24 hours of the bombardment.[158]

Soviet offensive on the Karelian Isthmus

Although the Karelian Isthmus front was less active in January than in December, the Soviets increased bombardments, wearing down the defenders and softening their fortifications. During daylight hours, the Finns took shelter inside their fortifications from the bombardments and repaired damage during the night. The situation led quickly to war exhaustion among the Finns, who lost over 3,000 soldiers in trench warfare. The Soviets also made occasional small infantry assaults with one or two companies.[159] Because of the shortage of ammunition, Finnish artillery emplacements were under orders to fire only against directly threatening ground attacks. On 1 February, the Soviets further escalated their artillery and air bombardments.[158]

Although the Soviets refined their tactics and morale improved, the generals were still willing to accept massive losses in order to reach their objectives. Attacks were screened by smoke, heavy artillery, and armour support, but the infantry charged in the open and in dense formations.[158] Unlike their tactics in December, Soviet tanks advanced in smaller numbers. The Finns could not easily eliminate tanks if infantry troops protected them.[160] After 10 days of constant artillery barrage, the Soviets achieved a breakthrough on the Western Karelian Isthmus in the second battle of Summa.[161]

On 11 February, the Soviets had approximately 460,000 soldiers, 3,350 artillery pieces, 3,000 tanks and 1,300 aircraft deployed on the Karelian Isthmus. The Red Army was constantly receiving new recruits after the breakthrough.[162] Opposing them, the Finns had eight divisions, totalling about 150,000 soldiers. One by one, the defenders' strongholds crumbled under the Soviet attacks and the Finns were forced to retreat. On 15 February, Mannerheim authorised a general retreat of the II Corps to a fallback line of defence.[163] On the eastern side of the isthmus, the Finns continued to resist Soviet assaults, repelling them in the battle of Taipale.[164]

Peace negotiations

Although the Finns attempted to re-open negotiations with Moscow by every means during the war, the Soviets did not respond. In early January, Finnish communist Hella Wuolijoki contacted the Finnish government. She offered to contact Moscow through the Soviet Union's ambassador to Sweden, Alexandra Kollontai. Wuolijoki departed for Stockholm and met Kollontai secretly at a hotel. Soon Molotov decided to extend recognition to the Ryti–Tanner government as the legal government of Finland and put an end to the puppet Terijoki Government of Kuusinen that the Soviets had set up.[165]

By mid-February, it became clear that the Finnish forces were rapidly approaching exhaustion. For the Soviets, casualties were high, the situation was a source of political embarrassment to the Soviet regime, and there was a risk of Franco-British intervention. With the spring thaw approaching, the Soviet forces risked becoming bogged down in the forests. Finnish Foreign Minister Väinö Tanner arrived in Stockholm on 12 February and negotiated the peace terms with the Soviets through the Swedes. German representatives, not aware that the negotiations were underway, suggested on 17 February that Finland negotiate with the Soviet Union.[166]

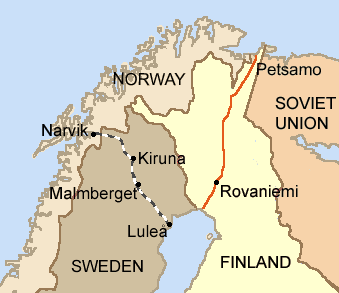

Both Germany and Sweden were keen to see an end to the Winter War. The Germans feared losing the iron ore fields in Northern Sweden and threatened to attack at once if the Swedes granted the Allied forces right of passage. The Germans even had an invasion plan against Scandinavian countries, called Studie Nord, which later became the full Operation Weserübung.[167] As the Finnish Cabinet hesitated in the face of harsh Soviet conditions, Sweden's King Gustav V made a public statement on 19 February in which he confirmed having declined Finnish pleas for support from Swedish troops. On 25 February, the Soviet peace terms were spelt out in detail. On 29 February, the Finnish government accepted the Soviet terms in principle and was willing to enter into negotiations.[168]

End of war in March

On 5 March, the Red Army advanced 10 to 15 km (6.2 to 9.3 mi) past the Mannerheim Line and entered the suburbs of Vyborg. The same day, the Red Army established a beachhead on the Western Gulf of Vyborg. The Finns proposed an armistice on 6 March, but the Soviets, wanting to keep the pressure on the Finnish government, declined the offer. The Finnish peace delegation travelled to Moscow via Stockholm and arrived on 7 March. The USSR made further demands as their military position was strong and improving. On 9 March, the Finnish military situation on the Karelian Isthmus was dire as troops were experiencing heavy casualties. Artillery ammunition was exhausted and weapons were wearing out. The Finnish government, noting that the hoped-for Franco-British military expedition would not arrive in time, as Norway and Sweden had not given the Allies right of passage, had little choice but to accept the Soviet terms.[170]

Moscow Peace Treaty

The Moscow Peace Treaty was signed in Moscow on 12 March 1940. A cease-fire took effect the next day at noon Leningrad time, 11 a.m. Helsinki time.[171] With it, Finland ceded a portion of Karelia, the entire Karelian Isthmus and land north of Lake Ladoga. The area included Finland's second-largest city of Vyborg, much of Finland's industrialised territory, and significant land still held by Finland's military—all in all, 11 percent of the territory and 30 percent of the economic assets of pre-war Finland.[47] Twelve percent of Finland's population, 422,000 Karelians, were evacuated and lost their homes.[172][173] Finland ceded a part of the region of Salla, Rybachy Peninsula in the Barents Sea, and four islands in the Gulf of Finland. The Hanko peninsula was leased to the Soviet Union as a military base for 30 years. The region of Petsamo, captured by the Red Army during the war, was returned to Finland according to the treaty.[174]

Finnish concessions and territorial losses exceeded Soviet pre-war demands. Before the war, the Soviet Union demanded that the frontier between the USSR and Finland on the Karelian Isthmus be moved westward to a point 30 kilometres (19 mi) east of Vyborg to the line between Koivisto and Lipola, that existing fortifications on the Karelian Isthmus be demolished, and the islands of Suursaari, Tytärsaari, and Koivisto in the Gulf of Finland and Rybachy Peninsula be ceded. In exchange, the Soviet Union proposed ceding Repola and Porajärvi from Eastern Karelia, an area twice as large as the territories originally demanded from the Finns.[175][176][177]

Foreign support

Foreign volunteers

World opinion largely supported the Finnish cause, and the Soviet aggression was generally deemed unjustified. World War II had not yet directly affected France, the United Kingdom or the United States; the Winter War was practically the only conflict in Europe at that time and thus held major world interest. Several foreign organisations sent material aid, and many countries granted credit and military materiel to Finland. Nazi Germany allowed arms to pass through Sweden to Finland, but after a Swedish newspaper made this public, Adolf Hitler initiated a policy of silence towards Finland, as part of improved German–Soviet relations following the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[178]

The largest foreign contingent came from neighbouring Sweden, which provided nearly 8,760 volunteers during the war. The Swedish Volunteer Corps, formed of Swedes, Norwegians (727 soldiers) and Danes (1,010 soldiers), fought on the northern front at Salla during the last weeks of the war. A Swedish unit of Gloster Gladiator fighters, named "the Flight Regiment 19" also participated. Swedish anti-air batteries with Bofors 40mm guns were responsible for air defence in northern Finland and the city of Turku.[179] Volunteers arrived from Hungary, Italy and Estonia. 350 American nationals of Finnish background volunteered, and 210 volunteers of other nationalities arrived in Finland before the war ended.[179] Max Manus, a Norwegian, fought in the Winter War before returning to Norway and later achieved fame as a resistance fighter during the German occupation of Norway. In total, Finland received 12,000 volunteers, 50 of whom died during the war.[180] The British actor Christopher Lee volunteered in the war for two weeks, but did not face combat.[181]

Franco-British intervention plans

France had been one of the earliest supporters of Finland during the Winter War. The French saw an opportunity to weaken Germany's major ally via a Finnish attack on the Soviet Union. France had another motive, preferring to have a major war in a remote part of Europe rather than on French soil. France planned to re‑arm the Polish exile units and transport them to the Finnish Arctic port of Petsamo. Another proposal was a massive air strike with Turkish cooperation against the Caucasus oil fields.[182]

The British, for their part, wanted to block the flow of iron ore from Swedish mines to Germany as the Swedes supplied up to 40 percent of Germany's iron demand.[182] The matter was raised by British Admiral Reginald Plunkett on 18 September 1939, and the next day Winston Churchill brought up the subject in the Chamberlain War Cabinet.[183] On 11 December, Churchill opined that the British should gain a foothold in Scandinavia with the objective to help the Finns, but without a war with the Soviet Union.[184] Because of the heavy German reliance on Northern Sweden's iron ore, Hitler had made it clear to the Swedish government in December that any Allied troops on Swedish soil would immediately provoke a German invasion.[185]

On 19 December, French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier introduced his plan to the General Staff and the War Cabinet. In his plan, Daladier created linkage between the war in Finland and the iron ore in Sweden.[184] There was a danger of Finland's possible fall under Soviet hegemony. In turn, Nazi Germany could occupy both Norway and Sweden. These two dictatorships could divide Scandinavia between them, as they had already done with Poland. The main motivation of the French and the British were to reduce the German war-making ability.[186]

The Military Coordination Committee met on 20 December in London, and two days later the French plan was put forward.[186] The Anglo-French Supreme War Council elected to send notes to Norway and Sweden on 27 December, urging the Norwegians and Swedes to help Finland and offer the Allies their support. Norway and Sweden rejected the offer on 5 January 1940.[185] The Allies came up with a new plan, in which they would demand that Norway and Sweden give them right of passage by citing a League of Nations resolution as justification. The expedition troops would disembark at the Norwegian port of Narvik and proceed by rail toward Finland, passing through the Swedish ore fields on the way. This demand was sent to Norway and Sweden on 6 January, but it was likewise rejected six days later.[187]

Stymied but not yet dissuaded from the possibility of action, the Allies formulated a final plan on 29 January. First, the Finns would make a formal request for assistance. Then, the Allies would ask Norway and Sweden for permission to move the "volunteers" across their territory. Finally, in order to protect the supply line from German actions, the Allies would send units ashore at Namsos, Bergen, and Trondheim. The operation would have required 100,000 British and 35,000 French soldiers with naval and air support. The supply convoys would sail on 12 March and the landings would begin on 20 March.[188] The end of the war on 13 March cancelled Franco-British plans to send troops to Finland through Northern Scandinavia.[189]

Aftermath and casualties

Finland

The 105-day war had a profound and depressing effect in Finland. Meaningful international support was minimal and arrived late, and the German blockade had prevented most armament shipments.[190] The 15-month period between the Winter War and the Operation Barbarossa-connected Continuation War was later called the Interim Peace.[174] After the end of the war, the situation of the Finnish Army on the Karelian Isthmus became a subject of debate in Finland. Orders had already been issued to prepare a retreat to the next line of defence in the Taipale sector. Estimates of how long the Red Army could have been delayed by retreat-and-stand operations varied from a few days to a few weeks,[191][192] or to a couple of months at most.[193] Karelian evacuees established an interest group, the Finnish Karelian League, after the war to defend Karelian rights and interests, and to find a way to return ceded regions of Karelia to Finland.[173][194] In 1940, Finland and Sweden conducted negotiations for a military alliance, but the negotiations ended once it became clear that both Germany and the Soviet Union opposed such an alliance.[195] During the Interim Peace, Finland established close ties with Germany in hopes of a chance to reclaim areas ceded to the Soviet Union.[196]

Immediately after the war, Helsinki officially announced 19,576 dead.[197] According to revised estimates in 2005 by Finnish historians, 25,904 people died or went missing and 43,557 were wounded on the Finnish side during the war.[F 12] Finnish and Russian researchers have estimated that there were 800-1,100 Finnish prisoners of war, of whom between 10 and 20 died. The Soviet Union repatriated 847 Finns after the War.[17] Air raids killed 957 civilians.[15] Between 20 and 30 tanks were destroyed and 62 aircraft were lost.[18]

Soviet Union

The Soviet General Staff Supreme Command (Stavka) met in April 1940, reviewed the lessons of the Finnish campaign, and recommended reforms. The role of frontline political commissars was reduced and old-fashioned ranks and forms of discipline were reintroduced. Clothing, equipment and tactics for winter operations were improved. Not all of the reforms had been completed by the time Germans initiated Operation Barbarossa 15 months later.[198]

During the period between the Winter War and perestroika in the late 1980s, Soviet historiography relied solely on Vyacheslav Molotov's speeches on the Winter War. In his radio speech of 29 November 1939, Molotov argued that the Soviet Union had tried to negotiate guarantees of security for Leningrad for two months. The Finns had taken a hostile stance to "please foreign imperialists". Finland had undertaken military provocation, and the Soviet Union could no longer abide by non-aggression pacts. According to Molotov, the Soviet Union did not want to occupy or annex Finland; the goal was purely to secure Leningrad.[199]

The official Soviet figure in 1940 for their dead was 48,745. More recent Russian estimates vary: in 1990, Mikhail Semiryaga claimed 53,522 dead and N. I. Baryshnikov, 53,500 dead. In 1997, Grigoriy Krivosheyev claimed 126,875 dead and missing, and total casualties of 391,783 with 188,671 wounded.[19] In 1991, Yuri Kilin claimed 63,990 dead and total casualties of 271,528. In 2007, he revised the estimate of dead to 134,000[20] and in 2012, he updated the estimate to 138,533 irretrievable losses.[200] In 2013, Pavel Petrov stated that the Russian State Military Archive has a database confirming 167,976 killed or missing along with the soldiers' names, dates of birth, and ranks.[21] There were 5,572 Soviet prisoners of war in Finland.[23] The prisoners' fate after repatriation is unclear—Western sources suspect they were killed at NKVD camps.[201][202]

Between 1,200 and 3,543 Soviet tanks were destroyed. The official figure was 611 tank casualties, but Yuri Kilin found a note received by the head of the Soviet General Staff, Boris Shaposhnikov, which reports 3,543 tank casualties and 316 tanks destroyed. According to the Finnish historian Ohto Manninen, the 7th Soviet Army lost 1,244 tanks during the breakthrough battles of the Mannerheim Line in mid-winter. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the Finnish estimate of the number of lost Soviet tanks was 1,000–1,200.[24][25][26] The Soviet Air Forces lost around 1,000 aircraft, but less than half of them were combat casualties.[26][27]

Germany

The Winter War was a political success for the Germans. Both the Red Army and the League of Nations were humiliated, and the Anglo-French Supreme War Council had been revealed to be chaotic and powerless. The German policy of neutrality was not popular in the homeland, and relations with Italy had suffered. After the Peace of Moscow, Germany improved its ties with Finland, and within two weeks Finno-German relations were at the top of the agenda.[203][39] More importantly, the very poor performance of the Red Army convinced Hitler that an attack on the Soviet Union would be successful.[204]

Allies

The Winter War laid bare the disorganisation and ineffectiveness of the Red Army as well as of the Allies. The Anglo-French Supreme War Council was unable to formulate a workable plan, revealing its unsuitability to make effective war in either Britain or France. This failure led to the collapse of the Daladier government in France.[205]

See also

- Finnish Civil War

- Continuation War

- International relations (1919–1939)

- Karelian question

- List of Finnish corps in the Winter War

- List of Finnish divisions in the Winter War

- List of wars involving Finland

- Military history of Finland during World War II

- Military history of the Soviet Union

- Phoney War

- Timeline of the Winter War

- Winter War in popular culture

- Simo Häyhä

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Commander of the Leningrad Military District Kiril Meretskov initially ran the overall operation against the Finns.[1] The command was passed on 9 December 1939 to the General Staff Supreme Command (later known as Stavka), directly under Kliment Voroshilov (chairman), Nikolai Kuznetsov, Joseph Stalin and Boris Shaposhnikov.[2][3] In January 1940, the Leningrad Military District was reformed and renamed "North-Western Front." Semyon Timoshenko was chosen Army Commander to break the Mannerheim Line.[4]

- ↑ At the beginning of the war, the Finns had 300,000 soldiers. The Finnish Army had only 250,028 rifles (total 281,594 firearms), but White Guards brought their own rifles (over 114,000 rifles, total 116,800 firearms) to the war. The Finnish Army reached its maximum strength at the beginning of March 1940 with 346,000 soldiers in uniform.[5][6]

- ↑ From 1919 onwards, the Finns possessed 32 French Renault FT tanks and few lighter tanks. These were unsuitable for the war and they were subsequently used as fixed pillboxes. The Finns bought 32 British Vickers 6-Ton tanks during 1936–39, but without weapons. Weapons were intended to be manufactured and installed in Finland. Only 10 tanks were fit for combat at the beginning of the conflict.[7]

- ↑ On 1 December 1939 the Finns had 114 combat aeroplanes fit for duty and seven aeroplanes for communication and observation purposes. Almost 100 aeroplanes were used for flight training purposes, not suitable for combat, or under repair. In total, the Finns had 173 aircraft and 43 reserve aircraft.[8]

- ↑ [9] 550,757 soldiers on 1 January 1940 and 760,578 soldiers by the beginning of March.[10] In the Leningrad Military District, 1,000,000 soldiers[11] and 20 divisions one month before the war and 58 divisions two weeks before its end.[12]

- ↑ At the beginning of the war the Soviets had 2,514 tanks and 718 armoured cars. The main battlefield was the Karelian Isthmus where the Soviets deployed 1,450 tanks. At the end of the war the Soviets had 6,541 tanks and 1,691 armoured cars. The most common tank type was T-26, but also BT type was very common.[13]

- ↑ This name is translated as follows: Finnish: talvisota, Swedish: vinterkriget, Russian: Зи́мняя война́, tr. Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (Russian: Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1939–1940 (Russian: Сове́тско-финляндская война́ 1939–1940) are often used in Russian historiography;[28][29][30] Russo–Finnish War 1939–1940 or Finno-Russian War 1939–1940 are used by the US Library of Congress' catalogue (see authority control).

- ↑ See the relevant section and the following sources:[31][32][33][34][35][36]

- ↑ See the relevant section and the following sources:[37][38][39]

- ↑ The Soviet role is confirmed in Khrushchev's memoirs, where he states that Artillery Marshal Grigory Kulik personally supervised the bombardment of the Soviet village.[70][71]

- ↑ See the following sources:[31][32][33][34][35]

- ↑ A detailed classification of dead and missing is as follows:[15][16]

- Dead, buried 16,766;

- Wounded, died of wounds 3,089;

- Dead, not buried, later declared as dead 3,503;

- Missing, declared as dead 1,712;

- Died as a prisoner of war 20;

- Other reasons (diseases, accidents, suicides) 677;

- Unknown 137;

- Died during the additional refresher training (diseases, accidents, suicides) 34.

Citations

- ↑ Edwards (2006), p. 93

- ↑ Edwards (2006), p. 125

- ↑ Manninen (2008), p. 14

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 204

- ↑ Palokangas (1999), pp. 299–300

- ↑ Juutilainen & Koskimaa (2005), p. 83

- ↑ Palokangas (1999), p. 318

- ↑ Peltonen (1999)

- ↑ Meltiukhov (2000): ch. 4, Table 10

- ↑ Krivosheyev (1997), p. 63

- ↑ Kilin (1999), p. 383

- ↑ Manninen (1994), p. 43

- ↑ Kantakoski (1998), p. 260

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 187

- 1 2 3 Kurenmaa and Lentilä (2005), p. 1152

- 1 2 Lentilä and Juutilainen (1999), p. 821

- 1 2 Malmi (1999), p. 792

- 1 2 3 4 Tillotson (1993), p. 160

- 1 2 3 Krivosheyev (1997), pp. 77–78

- 1 2 3 Kilin (2007b), p. 91

- 1 2 Petrov (2013)

- 1 2 Krivosheyev, Table 100

- 1 2 Manninen (1999b), p. 815

- 1 2 Kilin (1999) p. 381

- 1 2 Kantakoski (1998), p. 286

- 1 2 3 4 Manninen (1999b), pp. 810–811

- 1 2 Kilin (1999), p. 381

- ↑ Baryshnikov (2005)

- ↑ Kovalyov (2006)

- ↑ Shirokorad (2001)

- 1 2 Manninen (2008), pp. 37, 42, 43, 46, 49

- 1 2 Rentola (2003) pp. 188–217

- 1 2 3 Ravasz (2003) p. 3

- 1 2 Clemmesen and Faulkner (2013) p. 76

- 1 2 Zeiler and DuBois (2012) p. 210

- 1 2 Reiter (2009), p. 124

- 1 2 Chubaryan (2002), p. xvi

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), p. 17

- 1 2 3 Lightbody (2004), p. 55

- ↑ Kilin and Raunio (2007), p. 10

- ↑ Trotter 2002, pp. 3–5

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), pp. 4–6

- ↑ Jowett & Snodgrass (2006), p. 3

- ↑ Turtola (1999a), pp. 21–24

- ↑ Turtola (1999a), pp. 33–34

- ↑ Edwards (2006), pp. 26–27

- 1 2 Edwards (2006), p. 18

- ↑ Polvinen (1987), pp. 156–161, 237–238, 323, 454

- ↑ Engman (2007), pp. 452–454

- 1 2 3 Turtola (1999a), pp. 30–33

- ↑ Edwards (2006), p. 31

- ↑ Edwards (2006), pp. 43–46

- ↑ Van Dyke (1997), p. 13

- ↑ Edwards (2006), pp. 32–33

- ↑ Lightbody (2004), p. 52

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 15

- ↑ Edwards (2006), pp. 28–29

- ↑ Hallberg (2006), p. 226

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 12–13

- ↑ Turtola (1999a), pp. 32–33

- ↑ Turtola (1999a), pp. 34–35

- ↑ Engle and Paananen (1985), p. 6

- 1 2 3 Turtola (1999a), pp. 38–41

- ↑ Ries (1988), pp. 55–56

- ↑ Manninen (1999a), pp. 141–148

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 14–16

- ↑ Turtola (1999a), pp. 41–43

- ↑ Tanner (1950)

- ↑ Ries (1988), pp. 77–78

- ↑ Edwards (2006), p. 105

- 1 2 Turtola (1999a), pp. 44–45

- ↑ Tanner (1950), pp. 85–86

- ↑ Kilin (2007a), pp. 99–100

- ↑ Aptekar (2009)

- ↑ Yle News (2013)

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 34

- ↑ Conquest (2007), p. 450

- ↑ Bullock (1993), p. 489

- ↑ Glanz (1998), p. 58

- ↑ Ries (1988), p. 56

- ↑ Edwards (2006), p. 189

- ↑ Coox (1985), p. 996

- ↑ Coox (1985), pp. 994–995

- 1 2 Coox (1985), p. 997

- ↑ Goldman (2012), p. 167

- ↑ Langdon-Davies (1941), p. 7

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 35–36

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), pp. 38–39

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kilin and Raunio (2007), p. 13

- ↑ Trotter (2002)

- ↑ Leskinen and Juutilainen (1999)

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), pp. 42–44

- ↑ Laemlein (2013) pp. 95–99

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 47

- ↑ Jowett & Snodgrass (2006), p. 6

- ↑ Paskhover (2015)

- ↑ Russian State Military Archive F.34980 Op.14 D.108

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), pp. 48–51

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), p. 61

- ↑ League of Nations (1939), pp. 506, 540

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 58

- ↑ Soikkanen (1999), p. 235

- ↑ Geust; Uitto (2006), p. 54

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 69

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 72–73

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 76–78

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 51–55

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 121

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 53–54

- ↑ Paulaharju (1999), p. 292

- ↑ Paulaharju (1999), pp. 289–290

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), pp. 145–146

- 1 2 Paulaharju (1999), pp. 297–298

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 131–132

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 148–149

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), pp. 62–63

- ↑ Vuorenmaa (1999), pp. 494–495

- ↑ Laaksonen (1999), p. 407

- ↑ Laaksonen (1999), pp. 411–412

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 87–89

- ↑ Leskinen and Juutilainen (1999), p. 502

- ↑ Kilin and Raunio (2007), p. 113

- ↑ Juutilainen (1999a), pp. 504–505

- ↑ Juutilainen (1999a), p. 506

- ↑ Juutilainen (1999a), p. 520

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 110

- ↑ Juutilainen (1999a), pp. 510–511

- ↑ Juutilainen (1999a), p. 514

- ↑ Jowett & Snodgrass (2006), p. 44

- ↑ Juutilainen (1999a), pp. 516–517

- ↑ Vuorenmaa (1999), pp. 559–561

- ↑ Vuorenmaa (1999), p. 550

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 150

- ↑ Kulju (2007), p. 230

- ↑ Kulju (2007), p. 229

- ↑ Kantakoski (1998), p. 283

- ↑ Kulju (2007), pp. 217–218

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), pp. 171–174

- ↑ Leskinen and Juutilainen (1999), p. 164

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 178–180

- ↑ Vuorenmaa (1999), pp. 545–549

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 187

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), p. 193

- ↑ Kurenmaa and Lentilä (2005), p. 1152

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 187–188

- ↑ Tillotson (1993), p. 157

- ↑ Peltonen (1999), pp. 607–608

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 189

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 191–192

- ↑ Elfvegren (1999), p. 681

- ↑ Elfvegren (1999), p. 678

- ↑ Elfvegren (1999), p. 692

- ↑ Leskinen (1999), p. 130

- ↑ Silvast (1999), pp. 694–696

- ↑ Tillotson (1993), pp. 152–153

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 203–204

- ↑ Laaksonen (1999), pp. 424–425

- 1 2 3 Trotter (2002), pp. 214–215

- ↑ Laaksonen (1999), pp. 426–427

- ↑ Laaksonen (1999), p. 430

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 218

- ↑ Geust; Uitto (2006), p. 77

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 233

- ↑ Laaksonen (1999), p. 452

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 234–235

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 246–247

- ↑ Edwards (2006), p. 261

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 247–248

- ↑ Kilin and Raunio (2007), pp. 260–295

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 249–251

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 254

- ↑ Engle and Paananen (1985), pp. 142–143

- 1 2 Ahtiainen (2000)

- 1 2 Jowett & Snodgrass (2006), p. 10

- ↑ Van Dyke (1997), pp. 189–190

- ↑ Turtola (1999a), pp. 38–41

- ↑ Trotter 2002, pp. 14–16

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 194–202

- 1 2 Jowett & Snodgrass (2006), pp. 21–22

- ↑ Juutilainen (1999b), p. 776

- ↑ Rigby 2003, pp. 59–60.

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), pp. 235–236

- ↑ Edwards (2006), p. 141

- 1 2 Edwards (2006), p. 145

- 1 2 Trotter (2002), p. 237

- 1 2 Edwards (2006), p. 146

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 237–238

- ↑ Trotter (2002), pp. 238–239

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 239

- ↑ Edwards (2006), pp. 272–273

- ↑ Laaksonen (2005), p. 365

- ↑ Paasikivi (1958). p. 177

- ↑ Halsti (1955), p. 412

- ↑ Finnish Karelian League

- ↑ Turtola (1999b), p. 863

- ↑ Jowett & Snodgrass (2006), pp. 10–11

- ↑ Dallin (1942), p. 191

- ↑ Trotter (2002) p. 264

- ↑ Vihavainen (1999), pp. 893–896

- ↑ Soviet-Finnish War 1939–1940 and Red Army's Losses, in Proceedings of Petrozavodsk State University. Social Sciences & Humanities, Issue 5 (126)/2012.

- ↑ Van Dyke (1997), p. 191

- ↑ Trotter (2002), p. 263

- ↑ Edwards (2006), pp. 277–279

- ↑ Sedlar (2007), p. 8

- ↑ Edwards (2006), pp. 13–14

Works consulted

English

- Ahtiainen, Ilkka (16 July 2000). "The Never-Ending Karelia Question". Helsinki Times. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- Bullock, Alan (1993). Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-72994-5.

- Chubaryan, A. (2002). "Foreword". In Kulkov, E.; Rzheshevskii, O.; Shukman, H. Stalin and the Soviet-Finnish War, 1939–1940. Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-5203-0.

- Clemmesen, Michael H.; Faulkner, Marcus, eds. (2013). Northern European Overture to War, 1939–1941: From Memel to Barbarossa. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24908-0.

- Conquest, Robert (2007) [1991]. The Great Terror: A Reassessment (40th Anniversary ed.). Oxford University Press, US. ISBN 978-0-19-531700-8.

- Coox, Alvin D. (1985). Nomonhan: Japan against Russia, 1939. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1160-7.

- Dallin, David (1942). Soviet Russia's Foreign Policy, 1939–1942. Translated by Leon Dennen. Yale University Press.

- Edwards, Robert (2006). White Death: Russia's War on Finland 1939–40. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84630-7.

- Engle, Eloise; Paananen, Lauri (1985) [1973]. The Winter War: The Russo-Finnish Conflict, 1939–40. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-0149-1.

- Glanz, David (1998). Stumbling Colossus: The Red Army on the Eve of World War. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0879-9.

- Goldman, Stuart D. (2012). Nomonhan 1939, The Red Army's Victory That Shaped World War II. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-329-1.

- Jowett, Philip; Snodgrass, Brent (2006). Finland at War 1939–45. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-969-1.

- "Karjalan Liitto – Briefly in English". Finnish Karelian League. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- Krivosheyev, Grigoriy (1997b). Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century (1st ed.). Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-280-7.

- Laemlein, Tom (October 2013). "Where Will We Bury Them All?". American Rifleman. 161.

- Langdon-Davies, John (1941). Invasion in the Snow: A Study of Mechanized War. Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 1535780.

- League of Nations (1939-12-14). "Expulsion of the U.S.S.R.". League of Nations Official Journal.

- Lightbody, Bradley (2004). The Second World War: Ambitions to Nemesis. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22404-7.

- Reiter, Dan (2009). How Wars End (Illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 069114060X. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- Ries, Tomas (1988). Cold Will: The Defense of Finland (1st ed.). Brassey's Defence Publishers. ISBN 0-08-033592-6.