Chinese in New York City

The New York metropolitan area is home to the largest and most prominent ethnic Chinese population outside of Asia,[1][2] constituting the largest metropolitan Asian American group in the United States and the largest Asian-national metropolitan diaspora in the Western Hemisphere. The Chinese American population of the New York City metropolitan area was an estimated 812,410 as of 2015.[3]

New York City and the surrounding area, including Long Island and parts of New Jersey, is home to 12 Chinatowns, early U.S. racial ghettos where Chinese immigrants were made to live for economic survival and physical safety[4] that are now known as important sites of tourism and urban economic activity. Six Chinatowns[5] (or nine, including the emerging Chinatowns in Corona and Whitestone, Queens,[6] and East Harlem, Manhattan) are located in New York City proper, and one each is located in Nassau County, Long Island; Edison, New Jersey;[6] West Windsor, New Jersey; and Parsippany-Troy Hills, New Jersey. This excludes fledgling ethnic Chinese enclaves emerging throughout the New York metropolitan area, such as Jersey City, New Jersey; China City of America in Sullivan County, New York; and Dragon Springs in Deerpark, Orange County, New York.[7] The Chinese American community in the New York metropolitan area is rising rapidly in population as well as economic and political influence. Continuing significant immigration from Mainland China[8] has spurred the ongoing rise of the Chinese population in the New York metropolitan area; this immigration and its accompanying growth in the impact of the Chinese presence continue to be fueled by New York's status as an alpha global city, its high population density, its extensive mass transit system, and the New York metropolitan area's enormous economic marketplace.

History

Among the earliest documented arrivals of Chinese immigrants in New York City were of "sailors and peddlers" in the 1830s and again in 1847, when three students arrived to continue their education in the U.S. One of the scholars, Yung Wing, soon became the first Chinese American to graduate from a U.S. college in 1854, when Wing graduated from Yale University.

Many more Chinese immigrants arrived and settled in Lower Manhattan throughout the 1800s, including a 1870s wave of Chinese immigrants searching for "gold.[9]" By 1880, the enclave around Five Points was estimated to have from 200 to as many as 1,100 members.[9] However, the Chinese Exclusion Act, which went into effect in 1882, caused an abrupt decline in the number of Chinese who emigrated to New York and the rest of the United States.[9] Later, in 1943, the Chinese were given a small quota, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 caused a revival in Chinese immigration,[10] and the community's population gradually increased until 1968, when the quota was lifted and the Chinese American population skyrocketed, [9] and in 1992, New York City officially began providing language assistance for electoral materials in Chinese, given that this population had reached a critical mass in numbers.[11]

Demographics

New York City boroughs

New York City has the largest Chinese population of any city outside of Asia[12] and within the U.S. with an estimated population of 573,388 in 2014,[13] and continues to be a primary destination for new Chinese immigrants.[14] New York City is subdivided into official municipal boroughs, which themselves are home to significant Chinese populations, with Brooklyn and Queens, adjacently located on Long Island, leading the fastest growth.[15][16] After the City of New York itself, the boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn encompass the largest Chinese populations, respectively, of all municipalities in the United States.

| Rank | Borough | Chinese Americans | Density of Chinese Americans per square mile in borough | Percentage of Chinese Americans in borough's population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Queens, Chinatowns (皇后華埠) (2014)[17] | 237,484 | 2,178.8 | 10.2 |

| 2 | Brooklyn, Chinatowns (布魯克林華埠) (2014)[18] | 205,753 | 2,897.9 | 7.9 |

| 3 | Manhattan, Chinatown (曼哈頓華埠) (2014)[19] | 107,609 | 4,713.5 | 6.6 |

| 4 | Staten Island (2012) | 13,620 | 232.9 | 2.9 |

| 5 | The Bronx (2012) | 6,891 | 164 | 0.5 |

| New York City (2014) | 573,388[13] | 1,881.1 | 6.8 |

Large-scale immigration continues from China

In 2013, 19,645 Chinese legally immigrated to the New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA core based statistical area from Mainland China, greater than the combined totals for Los Angeles and San Francisco, the next two largest Chinese American gateways;[20] in 2012, this number was 24,763;[21] 28,390 in 2011;[22] and 19,811 in 2010.[23] These numbers do not include the remainder of the New York-Newark-Bridgeport, NY-NJ-CT-PA Combined Statistical Area, nor do they include the significantly smaller numbers of legal immigrants from Taiwan and Hong Kong. There has additionally been a consequential component of Chinese emigration of illegal origin, most notably Fuzhou people from Fujian and Wenzhounese from Zhejiang in mainland China, specifically destined for New York City,[24] beginning in the 1980s.

Quantification of the magnitude of this modality of emigration is imprecise and varies over time, but it appears to continue unabated on a significant basis. As of December 2015, China Airlines, China Eastern Airlines, and China Southern Airlines all served John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK), while Air China and Cathay Pacific Airways served both JFK and Newark Liberty International Airport in the New York metropolitan area – and among U.S. carriers, United Airlines flew non-stop from Newark to Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. Hainan Airlines has applied to launch non-stop flights between Tianjin and New York starting June 2016.[25]

Within the Chinese population, New York City is also home to between 150,000 and 200,000 Fuzhounese Americans, who have exerted a large influence upon the Chinese restaurant industry across the United States; the vast majority of the growing population of Fuzhounese Americans have settled in New York.

The Chinese immigrant population in New York City grew from 261,500 foreign-born individuals in 2000 to 350,000 in 2011, representing a more than 33% growth of that demographic.[26] Chinese immigrants represented 12,000 of the country's asylum requests in fiscal year 2013, of which 4,000 applied for asylum to the New York-area asylum office. Due to reports of widespread immigration fraud in the city that were uncovered in 2012, only about 15% of Chinese asylum applications in the New York asylum office were being approved annually as of 2013, compared to 40% of Chinese asylum requests nationwide.[27]

Movement within the metropolitan area

As many immigrant Chinese to New York City move up the socioeconomic ladder, many have relocated to the suburbs for more living space as well as seeking particular school districts for their children. In this process, new Chinese enclaves and Chinatown commercial districts have emerged and are growing in these suburbs, particularly in Nassau County on Long Island and in the four counties of New Jersey which start with the letter "M": Mercer County, Middlesex County, Monmouth County, and Morris County. The attractions of these counties to Chinese immigrants include wealthy and safe neighborhoods, vaunted educational systems, and ready accessibility to Manhattan by commuter rail.[28][29]

Geography

The Manhattan Chinatown was the original Chinatown.[30] Little Fuzhou in Manhattan is an ethnoculturally distinct neighborhood within the Manhattan Chinatown itself, populated primarily by Fujianese people. The Sunset Park neighborhood of Brooklyn houses another such Little Fuzhou. Queens and Brooklyn are home to other Chinatowns. The Flushing as well as Elmhurst areas of Queens and multiple burgeoning neighborhoods in Brooklyn[31] also have spawned the development of numerous other Chinatowns. Most of Manhattan, as well as Corona in Queens, the Brooklyn Heights and Park Slope areas of Brooklyn, and northeast Staten Island, have also received significant Chinese settlement.[30][32]

Chinatowns

Manhattan (曼哈頓華埠)

Manhattan's Chinatown holds the highest concentration of Chinese people in the Western Hemisphere.[33][34][35][36][37] Manhattan's Chinatown is actually divided into two different portions. The western portion is the older and original part of Manhattan's Chinatown, primarily dominated by Cantonese populations and known colloquially as the Cantonese Chinatown. Cantonese were the earlier settlers of Manhattan's Chinatown, originating mostly from Hong Kong and from Taishan in Guangdong Province, as well as from Shanghai.[38] They form most of the Chinese population of the area surrounded by Mott and Canal Streets.[38]

However, within Manhattan's expanding Chinatown lies Little Fuzhou or The Fuzhou Chinatown on East Broadway and surrounding streets, occupied predominantly by immigrants from the Fujian province of Mainland China. They are the later settlers, from Fuzhou, Fujian, forming the majority of the Chinese population in the vicinity of East Broadway.[38] This eastern portion of Manhattan's Chinatown developed much later after the Fuzhou immigrants began moving in.

Areas surrounding "Little Fuzhou" consist of significant numbers of Cantonese immigrants from the Guangdong of China, however the main Cantonese concentration is in the older western portion of Manhattan's Chinatown. Despite the fact that the Mandarin speaking communities were becoming established in Flushing and Elmhurst areas of Queens during the 1980s-90s and even though the Fuzhou immigrants spoke Mandarin often as well, due to their socioeconomic status, they could not afford the housing prices in Mandarin speaking enclaves in Queens, which were more middle class and the job opportunities were limited. They instead chose to settle in Manhattan's Chinatown for affordable housing and as well as the job opportunities that were available such as the seamstress factories and restaurants, despite the traditional Cantonese dominance until the 1990s. Eventually this pattern was repeated in Brooklyn's Sunset Park Chinatown, but on a much larger scale.

However, the Cantonese dialect that has dominated Chinatown for decades is being rapidly swept aside by Mandarin, the national language of China and the lingua franca due the influx of Fuzhou immigrants that often speak Mandarin and as well as there are now more Mandarin speaking visitors coming to visit the neighborhood.[39] Chinatown's modern borders are roughly Delancey Street on the north, Chambers Street on the south, East Broadway on the east, and Broadway on the west.[40]

Queens (皇后華埠)

New York City's satellite Chinatowns in Queens, as well as in Brooklyn, are thriving as traditionally urban enclaves, as large-scale Chinese immigration into New York continues,[42][43][44][45] with the largest metropolitan Chinese population outside Asia.[46]

The Flushing Chinatown, in the Flushing area of the borough of Queens in New York City, is one of the largest and fastest growing ethnic Chinese enclaves outside Asia, as well as within New York City itself. Main Street and the area to its west, particularly along Roosevelt Avenue, have become the primary nexus of Flushing Chinatown. However, Flushing Chinatown continues to expand southeastward along Kissena Boulevard and northward beyond Northern Boulevard. In the 1970s, a Chinese community established a foothold in the neighborhood of Flushing, whose demographic constituency had been predominantly non-Hispanic white. Taiwanese began the surge of immigration. It originally started off as Little Taipei or Little Taiwan due to the large Taiwanese population. Due to the then dominance of working class Cantonese immigrants of Manhattan's Chinatown including its poor housing conditions, they could not relate to them and settled in Flushing.

Later on, when other groups of Non-Cantonese Chinese, mostly speaking Mandarin started arriving into NYC, like the Taiwanese, they could not relate to Manhattan's then dominant Cantonese Chinatown, as a result they mainly settled with Taiwanese to be around Mandarin speakers. Later, Flushing's Chinatown would become the main center of different Chinese regional groups and cultures in NYC. By 1990, Asians constituted 41% of the population of the core area of Flushing, with Chinese in turn representing 41% of the Asian population.[47] However, ethnic Chinese are constituting an increasingly dominant proportion of the Asian population as well as of the overall population in Flushing and its Chinatown. A 1986 estimate by the Flushing Chinese Business Association approximated 60,000 Chinese in Flushing alone.[48] Mandarin Chinese[49] (including Northeastern Mandarin), Fuzhou dialect, Min Nan Fujianese, Wu Chinese, Beijing dialect, Wenzhounese, Shanghainese, Suzhou dialect, Hangzhou dialect, Changzhou dialect, Cantonese, Hokkien, and English are all prevalently spoken in Flushing Chinatown, while the Mongolian language is now emerging. Even the relatively obscure Dongbei style of cuisine indigenous to Northeast China is now available there.[50] Given its rapidly growing status, the Flushing Chinatown may have surpassed in size and population the original New York City Chinatown in the Borough of Manhattan, while Queens and Brooklyn vie for the largest Chinese population of any municipality in the United States other than New York City as a whole.

Elmhurst, another neighborhood in Queens, also has a large and growing Chinese community.[51] Previously a small area with Chinese shops on Broadway between 81st Street and Cornish Avenue, this new Chinatown has now expanded to 45th Avenue and Whitney Avenue. Since 2000, thousands of Chinese Americans have migrated into Whitestone, Queens (白石), given the sizeable presence of the neighboring Flushing Chinatown, and have continued their expansion eastward in Queens and into neighboring Nassau County (拿騷縣) on Long Island (長島).[52][53][54]

Brooklyn (布魯克林華埠)

By 1988, 90% of the storefronts on Eighth Avenue in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, were abandoned. Chinese immigrants then moved into this area, consisting not only of new arrivals from China, but also members of Manhattan's Chinatown seeking refuge from high rents, who flocked to the cheap property costs and rents of Sunset Park and formed the original Brooklyn Chinatown,[59] which now extends for 20 blocks along 8th Avenue, from 42nd to 62nd Streets. This relatively new but rapidly growing Chinatown located in Sunset Park was originally settled by Cantonese immigrants like Manhattan's Chinatown in the past. However, in the recent decade, an influx of Fuzhou immigrants has been pouring into Brooklyn's Chinatown and supplanting the Cantonese at a significantly higher rate than in Manhattan's Chinatown, and Brooklyn's Chinatown is now home to mostly Fuzhou immigrants. In the past, during the 1980s and 1990s, the majority of newly arriving Fuzhou immigrants settled within Manhattan's Chinatown, and the first Little Fuzhou community emerged within Manhattan's Chinatown; by the first decade of the 21st century, however, the epicenter of the massive Fuzhou influx had shifted to Brooklyn's Chinatown, which is now home to the fastest-growing and perhaps largest Fuzhou population in New York City. Unlike the Little Fuzhou in Manhattan's Chinatown, which remains surrounded by areas which continue to house significant populations of Cantonese, all of Brooklyn's Chinatown is swiftly consolidating into New York City's new Little Fuzhou. However, a growing community of Wenzhounese immigrants from China's Zhejiang is now also arriving in Brooklyn's Chinatown.[60][61] Also in contrast to Manhattan's Chinatown, which still successfully continues to carry a large Cantonese population and retain the large Cantonese community established decades ago in its western section, where Cantonese residents have a communal venue to shop, work, and socialize, Brooklyn's Chinatown is very quickly losing its Cantonese community identity.[62]

Like Manhattan's Chinatown during the 1980s-90s before the gentrification period came in, Brooklyn's Chinatown became the main affordable housing center for the Fuzhou immigrants and of job opportunities ranging from seamstress factories and restaurants despite that it was also dominated by Cantonese immigrants in the earlier years.

Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, as well as Avenue U in Homecrest, Brooklyn, in addition to Bay Ridge, Borough Park, Coney Island, Dyker Heights, Gravesend, and Marine Rark, have given rise to the development of Brooklyn's newer satellite Chinatowns, as evidenced by the growing number of Chinese-run fruit markets, restaurants, beauty and nail salons, small offices, and computer and consumer electronics dealers. While the foreign-born Chinese population in New York City jumped 35 percent between 2000 and 2013, to 353,000 from about 262,000, the foreign-born Chinese population in Brooklyn increased 49 percent during the same period, to 128,000 from 86,000, according to The New York Times. The emergence of multiple Chinatowns in Brooklyn is due to the overcrowding and high property values in Brooklyn's main Chinatown in Sunset Park, and many Cantonese immigrants have moved out of Sunset Park into these new areas. As a result, the newer emerging, but smaller Brooklyn's Chinatowns are primarily Cantonese dominated while the main Brooklyn Chinatown is increasingly dominated by Fuzhou emigres.[31]

List

- Chinatowns of NYC:

Culture

Languages

For much of the overall history of the Chinese community in New York City, Taishanese was the dominant Chinese dialect.[63] After 1965, an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong made Cantonese the dominant dialect for the next three decades.

Later on, during the 1970s-80s, Taiwanese and Fuzhou-speaking immigrants began to arrive into New York City. Taiwanese were settling into Flushing, Queens when it was still predominantly European American, while Fuzhou immigrants were settling in Manhattan's then very Cantonese-dominated Chinatown. The Taiwanese and Fuzhou people were the earliest Chinese immigrants to arrive into New York who spoke Mandarin but not Cantonese, although many spoke their regional Chinese dialects as well.

Since the mid 1990s, an influx of immigrants from various parts of Mainland China began arriving later on eventually, with the increased influence of Mandarin in the Chinese-speaking world, and a desire of Chinese parents to have their children learn this language, Mandarin has been in the process of becoming the dominant lingua franca among the Chinese population of New York City. In the Manhattan Chinatown, many newer immigrants who speak Mandarin live around East Broadway, while Chinatowns in Brooklyn and Queens have also witnessed influxes of Mandarin-speaking Chinese.[64]

However, the different Chinese cultural and language groups as well as socioeconomic statuses are often subdivided among different boroughs of New York City. In Queens, the Chinatowns are very diverse, composed of different Chinese regional groups mainly speaking Mandarin although speaking other dialects as well, and who are more often middle- or upper-middle class. As a result, the Mandarin lingua franca is primarily concentrated in Queens. However, since Manhattan's Chinatown and Brooklyn's Chinese enclaves still hold large Cantonese speaking populations, who were the earlier Chinese immigrants to arrive into New York City with the popularity of Hong Kong Cantonese cuisine and entertainment being widely available, the Cantonese dialect and culture still hold a large influence, and Cantonese is still a lingua franca in those enclaves.

Even though there are very large Fuzhou populations in Manhattan's Chinatown and Brooklyn's Chinese enclaves, many of whom speak Mandarin as well, the influence of Mandarin in those enclaves is as only one of the lingua francas in addition to Cantonese, rather than being the dominant one – unlike in the Chinese enclaves in Queens, where Mandarin is the most dominant lingua franca, despite the presence of a high diversity of Chinese regional languages in Queens – since there are fewer Mandarin speakers besides the Fuzhou population in Manhattan and Brooklyn than in Queens. However, in Brooklyn, Fuzhou speakers predominate in the large Chinatown in Sunset Park, while the several smaller emerging Chinatowns in various sections of Bensonhurst and in Sheepshead Bay are primarily Cantonese, unlike in Manhattan, where the Cantonese enclave and Fuzhou enclave are directly adjacent to each other.

Cuisine

Given that the New York City metropolitan area has become home to the largest overseas Chinese population outside of Asia,[65][66] all popular styles of regional Chinese cuisine have commensurately become ubiquitously accessible in New York City,[67] including Hakka, Taiwanese, Shanghainese, Hunanese, Szechuan, Cantonese, Fujianese, Xinjiang, Zhejiang, and Korean Chinese cuisine. Even the relatively obscure Dongbei style of cuisine indigenous to Northeast China is now available in Flushing, Queens,[68] as well as Mongolian cuisine and Uyghur cuisine.[69] The availability of the regional variations of Chinese cuisine originating from throughout the different Provinces of China is most apparent in the city's Chinatowns in Queens, particularly the Flushing Chinatown (法拉盛華埠), but is also notable in the city's Chinatowns in Brooklyn and Manhattan.

Kosher preparation of Chinese food

Kosher preparation of Chinese food is also widely available in New York City, given the metropolitan area's large Jewish and particularly Orthodox Jewish populations.The perception that American Jews eat at Chinese restaurants on Christmas Day is documented in media as a common stereotype with a basis in fact.[70][71][72] The tradition may have arisen from the lack of other open restaurants on Christmas Day, as well as the close proximity of Jewish and Chinese immigrants to each other in New York City. Kosher Chinese food is usually prepared in New York City, as well as in other large cities with Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods, under strict Rabbinical supervision as a prerequisite for Kosher certification.

News media

The World Journal, one of the largest Chinese-language newspapers outside of Asia, has its headquarters in Whitestone (白石), Queens,[73][74] while The Epoch Times, a multi-lingual, multinational newspaper with a significant Chinese language presence, is headquartered in Manhattan.[75] The Hong Kong-based, multinational Chinese-language newspaper Sing Tao Daily maintains its overseas headquarters in Chinatown, Manhattan. The Beijing-based, English-language newspaper China Daily publishes a U.S. edition, which is based in the 1500 Broadway skyscraper in Times Square.[76] In addition, the Global Chinese Times is published in Edison, Middlesex County, New Jersey,[77][78] to serve both a growing global readership and New Jersey's growing Chinese population of over 150,000 in 2016.[79]

Museums

The Museum of Chinese in America is located in the Manhattan Chinatown, at 215 Centre Street, and this prominent cultural institution has documented the Chinese American experience since 1980.

Chinese Lunar New Year

Chinese Lunar New Year is celebrated annually throughout New York City's Chinatowns. Chinese New Year was signed into law as an allowable school holiday in the State of New York by Governor Andrew Cuomo in December 2014, as absentee rates had run as high as 60% in some New York City schools on this day.[80]

Education

The Shuang Wen School is a public school in Manhattan's Chinatown, also known as P.S. 184M, as part of the New York City Department of Education, that offers a dual-language instructional program in Mandarin and English.[81] The Huaxia Edison Chinese School operates in Edison, New Jersey as a branch of the Huaxia Chinese School system. Chinese Americans compose a disproportionate enrollment relative to the general population in the nine elite public high schools of New York City, including Stuyvesant High School and Bronx Science High School.[82]

Transportation

A system of dollar vans operates between the different Chinatowns in New York City. The dollar vans (which are distinct from, and not to be confused with, Chinatown bus lines), go from Manhattan's Chinatown to places in Sunset Park, Brooklyn; Elmhurst, Queens; and Flushing, Queens. There is also a service from Flushing to Sunset Park that does not pass through Manhattan. Contrary to their name, the dollar vans' fares cost $2.50, which is cheaper than the New York City transit fares of $2.75 as of 2015.[83][84][85]

There are also intercity bus services that operate from the Chinatowns in New York City.[86][87]

As of 2016, the two largest Taiwanese airlines have provided free shuttle services to and from John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City for customers based in New Jersey.

- China Airlines's service stops in Fort Lee, Parsippany, and Jersey City[88]

- EVA Air's service stops in Jersey City, Piscataway, Fort Lee, and East Hanover.[89]

Political influence

The political stature of Chinese Americans in New York City has become prominent. As of 2017, Guo Wengui, a Chinese billionaire turned political activist, has been in self-imposed exile in New York City, where he owns a $US68 million apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, overlooking Central Park. He has continued to conduct a political agenda to bring attention to alleged corruption in the Chinese political system from his New York home.[91] Taiwan-born John Liu, former New York City Council member representing District 20, which includes Flushing Chinatown and other northern Queens neighborhoods, was elected to his current position of New York City Comptroller in November 2009, becoming the first Asian American to be elected to a citywide office in New York City.[92]. Concomitantly, Peter Koo, born in Shanghai, was elected to succeed Liu to assume this council membership seat. Margaret Chin became the first Chinese American woman representing Manhattan's Chinatown on the New York City Council, elected in 2009. Grace Meng is a member of the United States House of Representatives, representing New York's 6th congressional district in Queens since 2009. Of the more than 2,100 Asian Americans within the uniformed ranks of the New York Police Department in 2015 – about 6 percent of the total – roughly half were Chinese American, police statistics show, a number which has grown tenfold since 1990.[1] Yuh-Line Niou (Chinese: 牛毓琳) is a Taiwanese-American Democratic Party member of the New York State Assembly representing the 65th district in Lower Manhattan, elected in 2016, taking over the seat previously held by Sheldon Silver.[93]

Economic influence

The economic influence of Chinese in New York City is growing as well. The majority of cash purchases of New York City real estate in the first half of 2015 were transacted by Chinese as a combination of overseas Chinese and Chinese Americans.[94] The top three surnames of cash purchasers of Manhattan real estate during that time period were Chen, Liu, and Wong.[94] Chinese have also invested billion of dollars into New York commercial real estate since 2013.[95] According to China Daily, the ferris wheel under construction on Staten Island, slated to be among the world's tallest and most expensive with an estimated cost of US$500 million, has received US$170 million in funding from approximately 300 Chinese investors through the U.S. EB-5 immigrant investor program, which grants permanent residency to foreign investors in exchange for job-creating investments in the United States, with Chinese immigrating to New York City dominating this list.[96] Chinese billionaires have been buying New York property to be used as pied-à-terres, often priced in the tens of millions of U.S. dollars each,[97][98] and as of 2016, middle-class Chinese investors were purchasing real estate in New York.[99] Chinese companies have also been raising billions of dollars on stock exchanges in New York via initial public offerings.[100] The major Chinese banks maintain operational offices in New York City.

Water purity and availability

Water purity and availability are a lifeline for the economy of Chinese Americans in New York City, particularly in the Chinatowns. New York City is supplied with drinking water by the protected Catskill Mountains watershed.[101] As a result of the watershed's integrity and undisturbed natural water filtration system, New York is one of only four major cities in the United States the majority of whose drinking water is pure enough not to require purification by water treatment plants.[102] The Croton Watershed north of the city is undergoing construction of a US$3.2 billion water purification plant to augment New York City's water supply by an estimated 290 million gallons daily, representing a greater than 20% addition to the city's current availability of water.[103] The ongoing expansion of New York City Water Tunnel No. 3, an integral part of the New York City water supply system, is the largest capital construction project in the city's history,[104] with segments serving Manhattan and The Bronx completed, and with segments serving Brooklyn and Queens planned for construction in 2020.[105] Much of northern and central New Jersey is provided by reservoirs to provide fresh water, but numerous municipal wells exist which accomplish the same purpose.

Notable people

- Chinese New Yorkers (紐約華人)

_(cropped).jpg)

_in_1958.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Academia and humanities

- Anthony Chan – chief economist, JPMorgan Chase; former economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and economics professor at the University of Dayton[106]

- Peter Kwong – professor of Asian American studies at Hunter College and professor of sociology in the City University of New York system

- Betty Lee Sung – leading literary authority on Chinese Americans and former professor at City College of New York[107]

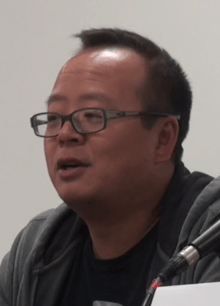

- Tim Wu – professor at Columbia Law School; ran unsuccessfully to become the first Chinese American lieutenant governor of New York State in 2014

Academia and sciences

- Chien-Shiung Wu – late experimental physicist and Columbia University professor

- David Ho – scientific researcher and the Irene Diamond professor at Rockefeller University

- Tsung-Dao Lee – university professor emeritus at Columbia University, Nobel Prize winner in physics

Business

- Sam Chang – real estate and hotel developer

- James S.C. Chao – shipping magnate and father of U.S. Cabinet nominee Elaine Chao

- Guo Wengui – billionaire businessman and political activist

- Charles Wang – owner, New York Islanders team of the National Hockey League

Entrepreneurship and technology

- Perry Chen – co-founder of Kickstarter

- Christopher Cheung – co-founder, Boxed

- Chieh Huang – CEO and co-founder, Boxed[108]

- William Fong – co-founder, Boxed

- David Zhu – co-founder, Enterproid

Law, politics, and diplomacy

- Margaret Chan – New York State Supreme Court Civil Branch justice in Manhattan[109][110]

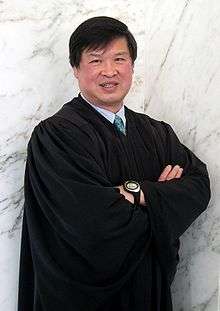

- Denny Chin – justice on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in Manhattan

- Margaret Chin – first Chinese American woman elected to represent Manhattan's Chinatown on the New York City Council in 2009

- Peter Koo – New York City councilman elected in 2009 to represent District 20 in Queens

- Li Baodong – President of the United Nations Security Council during months in 2011 and 2012

- Doris Ling-Cohan – New York State Supreme Court Civil Branch justice in Manhattan[109]

- Liu Jieyi – Permanent Representative of China to the United Nations from 2013 to 2017

- John Liu – first Chinese American to be elected New York City Comptroller in 2009

- Ma Zhaoxu – current Permanent Representative of China to the United Nations, since January 2018

- Grace Meng – member of the United States House of Representatives, representing New York's 6th congressional district in Queens

- Yuh-Line Niou – member of the New York State Assembly, representing the 65th District in Lower Manhattan, elected in November 2016

- Wenjian Liu – first Chinese American officer in the New York City Police Department to die in the line of duty in 2014

- Wenliang Wang – honorary chairman, NYU Center on U.S.-China relations[111]

- Peter Yew – Chinese Americans first protested police brutality with high-profile activism outside New York City Hall in May 1975, after the beating of this 27-year-old Chinese-American engineer who was a bystander at the scene of a traffic dispute in Chinatown in Manhattan.[1]

- Zhang Yesui – Permanent Representative of China to the United Nations from 2008 to 2010

Media

- Ai Heping – journalist, China Daily[94]

- An Rong Xu – photographer, journalist[112][113]

- Kathy YL Chan – journalist, Bloomberg News[114]

- Sewell Chan – journalist, The New York Times

- Laura Chang – journalist, editor of the Booming blog, The New York Times

- Adrian Chen – investigative journalist, staff writer at The New Yorker

- Aria Hangyu Chen – multimedia journalist[115]

- Brian X. Chen – lead consumer technology journalist, The New York Times[116]

- Caroline Chen – journalist, Bloomberg News[117][118]

- David W. Chen – investigative journalist, City Hall bureau chief, The New York Times[119]

- Stefanos Chen – real estate reporter, The New York Times[120]

- Evelyn Cheng – journalist, CNBC[121][122]

- Roger Cheng – executive editor in charge of breaking news, CNET News[123]

- Paul Cheung – journalist, global director of interactive and digital news production, The Associated Press[124]

- Ronny Chieng – comedian

- Dominic Chu – journalist, CNBC[125]

- Connie Chung – journalist[126]

- James Dao – op-ed editor, The New York Times[127]

- Wendi Deng – media personality, film producer, and businessperson

- Scarlet Fu – Bloomberg Television anchor and New York Stock Exchange reporter[128]

- Amy He – journalist, China Daily[129]

- Angela He – corporate communications specialist, The New York Times[130]

- Hezi Jiang – journalist, China Daily[131][132]

- Hong Xiao – journalist, China Daily[96]

- Cindy Hsu – news reporter at WCBS-TV

- Winnie Hu – journalist, The New York Times[133][134]

- Eddie Huang – writer, author of Fresh Off the Boat: A Memoir

- Jing Cao – journalist, Bloomberg News[135]

- K.K. Rebecca Lai – graphics editor, The New York Times[136]

- Jennifer 8. Lee – journalist, credits including The New York Times

- Melissa Lee – news anchor, Fast Money on CNBC[137]

- Betty Liu – news anchor, Bloomberg Television

- Michael Luo – journalist, The New York Times[138][139]

- Alfred Ng – associate engagement editor, New York Daily News[140]

- Niu Yue – journalist, China Daily[96]

- Gillian Tan – Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering private equity and mergers and acquisitions[141]

- Terry Tang – deputy editorial page editor, The New York Times[142]

- Kaity Tong – journalist, news anchor

- Christine Wang – news editor, CNBC[143]

- Lu Wang – journalist, Bloomberg News[144]

- Vivian Wang – journalist, The New York Times[145]

- Andrea Wong – journalist, Bloomberg News[146]

- Jeff Yang – media consultant, "Tao Jones" columnist for The Wall Street Journal

- Vivian Yee – journalist, The New York Times[147]

- Claudia Yeung – communications director, Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office, New York[148]

- William Yu – digital media strategist[149][150]

- Jada Yuan – travel correspondent, The New York Times[151]

- Benjamin P. Zhang – journalist, Business Insider[152]

Theater, arts, and culture

- Awkwafina (Nora Lum) – actress and rapper

- Richard Chai – fashion designer

- Kevin Chan – fashion designer[153][154]

- Angel Chang – fashion designer

- David Chu – fashion designer

- Grace Zia Chu – late author of Chinese cookbooks

- Diana Eng – fashion designer

- Vivienne Hu – fashion designer[155]

- David Henry Hwang – Broadway playwright, librettist, and screenwriter

- Jonathan Koon – fashion designer

- Derek Lam – fashion designer

- Phillip Lim – fashion designer

- Jenny Lin – pianist

- Joseph Lin – violinist

- Lucy Liu – actress, fashion model, and artist

- Liu Wen – supermodel

- Angela Mao – former actress and martial artist, aka "Lady Kung Fu"[156]

- Peter Mui – fashion designer, actor, and musician

- Mary Ping – fashion designer

- Shen Wei – choreographer, stage designer

- Mimi So – jewelry designer

- Peter Som – fashion designer

- Anna Sui – fashion designer

- Brandon Sun – fashion designer[157]

- Fei Fei Sun – supermodel

- Vivienne Tam – fashion designer

- Ling Tan – supermodel

- Alexander Wang – fashion designer[158]

- Vera Wang – fashion designer

- Yuja Wang – concert pianist

- Jason Wu – fashion designer

- Sophia Yan – classical pianist[159]

- Xin Ying – modern dancer[160]

- Yeohlee Teng – fashion designer[161]

- Joe Zee – fashion stylist

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Vivian Yee (February 22, 2015). "Indictment of New York Officer Divides Chinese-Americans". The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- 1 2 "Chinese New Year 2012 in Flushing". QueensBuzz.com. January 25, 2012. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑ "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES 2015 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA Chinese alone". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ↑ Goyette, Braden (2014-11-11). "How Racism Created America's Chinatowns". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- ↑ Kirk Semple (June 23, 2011). "Asian New Yorkers Seek Power to Match Numbers". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

- 1 2 Lawrence A. McGlinn (2002). "Beyond Chinatown: Dual Immigration and the Chinese Population of Metropolitan New York City, 2000" (PDF). Middle States Geographer. 35 (1153): 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012. Retrieved 2014-10-03.

- ↑ "Dragon Springs - Located in beautiful Deerpark, NY". Dragon Springs. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

There is no other place in the world like Dragon Springs. It combines the natural beauty of New York State with ancient Chinese architecture, performing arts, academic learning, and spiritual meditation.

- ↑ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: Lawful Permanent Residents 2013 Supplementary Tables - Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Waxman, Sarah. "The History of New York's Chinatown". ny.com. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ↑ Lee, Josephine Tsui Yeh, p. 7,

- ↑ "A Brief History of Electoral Law in New York". Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ↑ "NYC Population Facts". www1.nyc.gov. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- 1 2 "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES – 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates – New York City – Chinese alone". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ↑ "Kings County (Brooklyn Borough), New York QuickLinks". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ↑ "Queens County (Queens Borough), New York QuickLinks". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ↑ "Selected Population Profile in the United States 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates – Queens County, New York Chinese alone". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Selected Population Profile in the United States 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates – Kings County, New York Chinese alone". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Selected Population Profile in the United States 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates – New York County, New York Chinese alone". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status by Leading Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) of Residence and Region and Country of Birth: Fiscal Year 2013". Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2013. Department of Homeland Security. 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Persons Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status by Leading Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) of Residence and Region and Country of Birth: Fiscal Year 2012". Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012. Department of Homeland Security. 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Persons Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status by Leading Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) of Residence and Region and Country of Birth: Fiscal Year 2011". Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011. Department of Homeland Security. 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Persons Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status by Leading Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) of Residence and Region and Country of Birth: Fiscal Year 2010". Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2010. Department of Homeland Security. 2010. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ↑ John Marzulli (May 9, 2011). "Malaysian man smuggled illegal Chinese immigrants into Brooklyn using Queen Mary 2: authorities". Copyright 2012 NY Daily News.com. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Hainan Airlines Plans to Launch New York and Vancouver Flights in 2016". China National Tourist Office, New York. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ↑ Semple, Kirk (2013-12-18). "Immigration Remakes and Sustains New York, Report Finds". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ Goldstein, Kirk Semple, Joseph; Singer, Jeffrey E. (2014-02-22). "Asylum Fraud in Chinatown: An Industry of Lies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ Accessed August 19, 2018.

- ↑ Accessed August 19, 2018.

- 1 2 Lee, Josephine Tsui Yeh, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Liz Robbins (April 15, 2015). "Influx of Chinese Immigrants Is Reshaping Large Parts of Brooklyn". The New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ↑ McGlinn, Lawrence A. (2002). "Beyond Chinatown: Dual immigration and the Chinese population of metropolitan New York City, 2000" (PDF). Middle States Geographer (35): 114–115. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ Lawrence A. McGlinn, Department of Geography SUNY-New Paltz. "BEYOND CHINATOWN: DUAL IMMIGRATION AND THE CHINESE POPULATION OF METROPOLITAN NEW YORK CITY, 2000, Page 4" (PDF). Middle States Geographer, 2002, 35: 110–119, Journal of the Middle States Division of the Association of American Geographers. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "Chinatown New York City Fact Sheet" (PDF). www.explorechinatown.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "Chinatown". Indo New York. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Sarah Waxman. "The History of New York's Chinatown". Mediabridge Infosystems, Inc. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ David M. Reimers. Still the golden door: the Third ... – Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- 1 2 3 Lam, Jen; Anish Parekh; Tritia Thomrongnawasouvad (2001). "Chinatown: Chinese in New York City". Voices of New York. NYU. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ↑ Semple, Kirk (October 21, 2009). "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ Hay, Mark (July 12, 2010). "The Chinatown Question;". Capital. Retrieved 2013-09-07.

- ↑ Melia Robinson (May 27, 2015). "This is what it's like in one of the biggest and fastest growing Chinatowns in the world". Business Insider. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- ↑ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- ↑ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2010 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- ↑ John Marzulli (May 9, 2011). "Malaysian man smuggled illegal Chinese immigrants into Brooklyn using Queen Mary 2: authorities". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- ↑ "Chinese New Year 2012 in Flushing". QueensBuzz.com. January 25, 2012. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- ↑ Nancy Foner (2001). New immigrants in New York. Columbia University Press. pp. 158–161. ISBN 978-0-231-12414-0.

- ↑ Hsiang-shui Chen. "Chinese in Chinatown and Flushing". Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- ↑ Semple, Kirk (October 21, 2009). "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- ↑ Moskin, Julia (February 9, 2010). "Northeast China Branches Out in Flushing". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ↑ Marques, Aminda (August 4, 1985). "IF YOU'RE THINKING OF LIVING IN; ELMHURST". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ↑ Heng Shao (2014-04-10). "Join The Great Gatsby: Chinese Real Estate Buyers Fan Out To Long Island's North Shore". Forbes. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ↑ Michelle Conlin and Maggie Lu Yueyang (2014-04-25). "The Chinese take Manhattan: replace Russians as top apartment buyers". Thomson Reuters. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ↑ Carol Hymowitz (2014-10-27). "One Percenters Drop Six Figures at Long Island Mall". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2013 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2013 Supplemental Table 1". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 1". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Brooklyn Chinese-American Association: About BCA". bca.net. Brooklyn Chinese-American Association. Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ↑ Zhao, Xiaojian (January 19, 2010). "The new Chinese America: Class, economy, and social hierarchy". ISBN 978-0-8135-4692-6.

- ↑ "WenZhounese in New York". WenZhounese.info. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ↑ "Indy Press NY". www.indypressny.org.

- ↑ Semple, Kirk. "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin." The New York Times. October 21, 2009. p. 2. Retrieved on March 22, 2014.

- ↑ Semple, Kirk. "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin." The New York Times. October 21, 2009. p. 1. Retrieved on March 22, 2014.

- ↑ Vivian Yee (February 22, 2015). "Indictment of New York Officer Divides Chinese-Americans". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ↑ "Chinese New Year 2012 in Flushing". QueensBuzz.com. January 25, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ↑ Julia Moskin. "Let the Meals Begin: Finding Beijing in Flushing". The New York Times. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ↑ Moskin, Julia (2010-02-09). "Northeast China Branches Out in Flushing". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ↑ Max Falkowitz (August 25, 2018). "A World of Food, Outside the U.S. Open Gates". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ↑ "Why Do American Jews Eat Chinese Food on Christmas? — The Atlantic". Theatlantic.com. 2014-12-23. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ↑ "'Tis the season: Why do Jews eat Chinese food on Christmas? - Jewish World Features - Israel News". Haaretz. 2014-12-24. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ↑ "Movies and Chinese Food: The Jewish Christmas Tradition | Isaac Zablocki". Huffingtonpost.com. 2017-12-06. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ↑ "Contact Us (Page in Chinese) World Journal. Retrieved on November 19, 2011. "New York Headquarters 141-07 20th Ave. Whitestone, NY 11357"

- ↑ Machleder, Elaine. "New World, New Look / Chinese-language daily gets a makeover." Newsday. March 30, 1998. A25 News. Retrieved on November 19, 2011. "Its headquarters and printing facilities have been in Whitestone since 1980[...]"

- ↑ "Contact Us". Epoch Times. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ↑ "China Daily USA Contact Us". China Daily Information Co. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed June 13, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed June 13, 2016.

- ↑ "ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES 2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates - New Jersey". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ↑ "New law will let schools in New York state close for Chinese Lunar New Year, other religious holidays". Syracuse Media Group. December 26, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Inside Schools The Center for New York City Affairs at The New School - P.S. 184 Shuang Wen". The Center for New York City Affairs at The New School. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed October 17, 2015.

- ↑ Reiss, Aaron. "New York's Shadow Transit". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ↑ Margonelli, Lisa (October 5, 2011). "The (Illegal) Private Bus System That Works". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ↑ "The Brief Wondrous Life of the One Dollar Bus". Flushing Exceptionalism. August 19, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ↑ "The Amazing Chinatown Bus Network". Motherboard. November 27, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ↑ "All Aboard, Next Stop Chinatown". Hyphen Magazine. 2007-08-01. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ "Free Shuttle Service To/From JFK Airport". China Airlines. September 15, 2015. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Service to Connect PA & NJ." EVA Air. Retrieved on February 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Tuidang Movement". Places to Go In US. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ Michael Forsythe and Alexandra Stevenson (May 30, 2017). "The Billionaire Gadfly in Exile Who Stared Down Beijing". The New York Times. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

The biggest political story in China this year isn’t in Beijing. It isn’t even in China. It’s centered at a $68 million apartment overlooking Central Park in Manhattan.

- ↑ Victoria Cavaliere (November 4, 2009). "Liu Becomes First Asian-American in City-Wide Office". NBC. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Yuh-Line Niou Defeats Sheldon Silver Ally in Primary for His Old Assembly Seat". The New York Times. September 14, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Accessed October 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Here's Proof That China Loves New York City Real Estate". Curbed NY. May 14, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Niu Yue and Hong Xiao (July 21, 2015). "Chinese invest in world's tallest Ferris wheel". China Daily. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ↑ Candace Taylor (October 24, 2016). "Chinese Billionaire Nabs One57 Condo for a Mere $23.5 Million". The Wall Street Journal, via MSN. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ↑ Michael Forsythe and Alexandra Stevenson (May 30, 2017). "The Billionaire Gadfly in Exile Who Stared Down Beijing". The New York Times. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ↑ Emily Feng and Alexandra Stevenson (December 11, 2016). "Small Investors Join China's Tycoons in Sending Money Abroad". The New York Times. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ↑ Jethro Mullen (October 27, 2016). "This year's biggest U.S. IPO is by a Chinese delivery firm". CNN Money. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Current Reservoir Levels". New York City Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ↑ Lustgarten, Abrahm (August 6, 2008). "City's Drinking Water Feared Endangered; $10B Cost Seen". The New York Sun. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (July 23, 2014). "Quiet Milestone in Project to Bring Croton Water Back to New York City". The New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ↑ Flegenheimer, Matt (October 16, 2013). "After Decades, a Water Tunnel Can Now Serve All of Manhattan". The New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ↑ Jim Dwyer (April 6, 2016). "De Blasio Adding Money for Water Tunnel in Brooklyn and Queens". The New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed September 21, 2015.

- ↑ Lee Sung Accessed April 15, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed October 25, 2016.

- 1 2 Accessed September 22, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed September 22, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed October 1, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed November 27, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed November 27, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed November 16, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed June 8, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed October 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Caroline Chen". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

aroline Chen is a reporter for Bloomberg News in New York.

- ↑ Caroline Chen and Simeon Bennett (March 25, 2014). "China Smog at Center of Air Pollution Deaths Cited by WHO". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed November 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Stefanos Chen". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ↑ Evelyn Cheng (March 5, 2015). "iSectors' Chuck Self speaks to Evelyn Cheng of CNBC on markets and QE". iSectors. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Evelyn Cheng (@chengevelyn) - Twitter". twitter.com.

- ↑ "Roger Cheng, New York – A little about me". CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Paul Cheung Bio". Paul Cheung. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed August 7, 2018.

- ↑ Dan Rosenblum (April 13, 2012). "At awards ceremony for ethnic and indie press, Connie Chung describes big media as 'a very male-oriented, very white-oriented executive suite'". Capital. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed November 22, 2016.

- ↑ Linette Lopez (May 30, 2012). "You Can't See It, But Here's What Bloomberg TV's Scarlet Fu Is Wearing When She Reports From The NYSE". Business Insider Inc. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed July 28, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed October 1, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed April 22, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed April 22, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed August 4, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed August 4, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed December 13, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed June 28, 2017.

- ↑ Christopher A. Pape. "Fast Times with Melissa Lee". THE RESIDENT. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ Michael Luo (October 10, 2016). "'Go Back to China': Readers Respond to Racist Insults Shouted at a New York Times Editor". The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- ↑ Hope King (October 10, 2016). "#Thisis2016 rallies Asian Americans against racist encounters". CNN Money. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed January 18, 2016

- ↑ Accessed February 5, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed July 28, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed August 7, 2018.

- ↑ Accessed January 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Vivian Wang". The New York Times. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ "Andrea Wong - Verified". Muck Rack. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ↑ "Vivian Yee". Sawhorse Media. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Key Personnel". Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. April 14, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ↑ Accessed May 16, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed May 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Introducing Our 52 Places Traveler". The New York Times. January 10, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- ↑ Accessed July 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Daring Origins: Kevin Chan, Fashion Industry Upstart". Dare Greatly. February 28, 2016. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed February 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Swarovski Collective - Vivienne Hu". Swarovski. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ↑ Accessed November 5, 2016.

- ↑ Blue Carreon (April 27, 2015). "Brandon Sun: The Asian-American Designer You Need To Know Now". Forbes. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ↑ Diane Von Furstenberg. "Alexander Wang Gang". Interview Magazine. Retrieved February 12, 2015.

- ↑ Lee, Jonathan H. X.; Nadeau, Kathleen M. (February 25, 2018). "Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife". ABC-CLIO – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Dancers". Martha Graham Dance Company. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ↑ Accessed August 25, 2015.

Citations

- Lee, Josephine Tsui Yueh. New York City's Chinese Community. Arcadia Publishing, 2007. ISBN 0738550183, 9780738550183.