Chinatown, Honolulu

|

Chinatown Historic District | |

|

Site of former Wo Fat restaurant | |

| |

| Location | Beretania Street, Nuuanu Stream, Nuuanu Avenue, and Honolulu Harbor, Honolulu, Hawaii |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 21°18′44″N 157°51′46″W / 21.31222°N 157.86278°WCoordinates: 21°18′44″N 157°51′46″W / 21.31222°N 157.86278°W |

| Area | 36 acres (15 ha) |

| Built | 1900 |

| NRHP reference # | 73000658[1] |

| Added to NRHP | January 17, 1973 |

The Chinatown Historic District is a Chinatown neighborhood of Honolulu, Hawaii known for its Chinese American community, and is one of the oldest Chinatowns in the United States.

History

The area was probably used by fishermen in ancient Hawaii but little evidence of this remains. Kealiʻimaikaʻi, the brother of Kamehameha I lived in the area at the end of the 18th century. One of the first early settlers from outside was Isaac Davis and lived there until 1810.[2] Spaniard Don Francisco de Paula Marín lived in the southern end of the area in the early 19th century, and planted a vineyard in the northern end, for which Vineyard Boulevard is named.[3]

During the 19th century laborers were imported from China to work on sugar plantations in Hawaii. Many became merchants after their contracts expired and moved to this area. The ethnic makeup has alway been diverse, peaking at about 56% Chinese people in the 1900 census, and then declining.[4] Honolulu is traditionally known in Chinese as 檀香山 (Tánxiāngshān), meaning Sandalwood Mountain.

Two major fires destroyed many buildings in 1886 and 1900. The 1900 fire was started in an attempt to destroy a building infected with bubonic Plague, which had been confirmed December 12, 1899. Schools were closed and 7000 residents of the area were put under quarantine. After 13 people died, the Board of Health ordered structures suspected of being infected to be burned. Residents were evacuated, and a few buildings were successfully destroyed while the Honolulu Fire Department stood by. However, on January 20, 1900 the fire got out of control after winds shifted, and destroyed most of the neighborhood instead.[5][6] Many of the buildings date from 1901. Very few were over four stories tall.[4]

There is conflicting information about the boundaries that make up Chinatown. One source identifies the natural boundary to the south as Honolulu Harbor, and to the northwest Nuʻuanu stream. Beretania Street is usually considered the northeastern boundary,[7] and the southeastern boundary is Nuʻuanu Avenue. A few blocks to the east is the Hawaii Capital Historic District, and adjacent to the south is the Merchant Street Historic District. The Hawaiian language newspaper [[Nupepa Kuokoa]] describes it as ...that place "Chinatown" is that whole area from West side of Kukui Street until the river mouth called Makaaho, then travel straight until reaching Hotel street; and travel on [Hotel] this street on the West side until reaching Konia Street, and travel until you reach King St.[8]

In 1904 the Oahu Market was opened by Tuck Young at the corner of King and Kekaulike streets, coordinates 21°18′45″N 157°51′51″W / 21.31250°N 157.86417°W. The simply designed functional construction (a large open-air but covered space divided into stalls) remains in use today for selling fresh fish and produce.[9]

Bubonic Plague (1899-1900)

King Kamehameha III created the Board of Health (BOH) on December 13, 1850. This became the first Board of Health in the United States. The BOH was established to supervise the public health of the people of Hawaii, and to protect them against epidemic diseases. The BOH played an integral role during the Bubonic Plague at which time was under the control of three physicians: Nathaniel B. Emerson, Francis R. Day and Clifford B. Wood. The situation had become so dire in Honolulu that Emerson, Day and Wood were afforded absolute dictatorial authority over Hawaii. This comes as the result of an agreement between the President of the Provisional Hawaiian Government, Mr. Sanford Ballard Dole, and the Attorney General, Mr. Henry E. Cooper who concurred that nothing should impede the battle of the "dread disease." [10]

According to the Annual Reports (1899-1960) published by the Hawaii State Department of Health, the first case of the bubonic plague was found in Yon Chong. Chong was a 22 year old Chinese male who worked as a bookkeeper in Chinatown, Honolulu.[11] It goes on and states that Chong fell sick on December 9, 1899, and formed buboes. The formation of the buboes is what led his attending physician to suspect the plague. A jointly conducted diagnosis was performed by other doctors, who confirmed the suspicion. Their diagnosis was reported to the President of the BOH Henry Ernest Cooper on December 11, 1899. Yon Chong died the following day, and President Cooper made an announcement about this first case of bubonic plague death to the public.[11][12]

After the public announcement, President Cooper ordered an immediate military quarantine of the Chinatown area. Also, in hoping to contain the plague in Honolulu, the BOH closed the Honolulu port to both incoming and outgoing vessels. According to the BOH official records, only three human cases of the plague was recorded during the quarantine. On December 19, 1899, BOH lifted the quaratine of Chinatown and Honolulu Harbor.[12] However, only five days after the lift, nine more cases was reported by the BOH. Out of the total 12 cases of plague reported, there were 11 deaths reported by the BOH.[12]

The Bubonic plague in Chinatown, Honolulu was not stopped till March 31, 1900. A total of 71 cases and 61 fatalities were reported by BOH.

Pestis in Hawaii

Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of the bubonic plague is transmitted by its vector, the oriental rat flea and has been historically propagated along various trade routes to the west from China. Although the original introduction of the oriental rat flea to Hawaii is unknown, one historical incident may mark such an important event. In 1899, the Nippon Maru anchored in Honolulu Harbor on its way to San Francisco, reporting the death of a Chinese passenger. After inspection, the ship had been quarantined to Quarantine Island, better known today as Sand Island. After a week-long stay there, the ship had been cleared to travel on to San Francisco. According to one record, due diligence was executed on the part of the Board of Health with respect to the passengers and goods, though little attention was paid to the chance of rats escaping and going ashore. This is because it had not yet discovered that the rodents were the carriers of the vector that carried the pestis bacteria.[10]

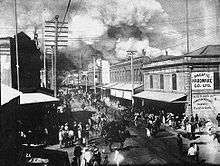

Great Honolulu Chinatown Fire of 1900

| Great Honolulu Chinatown Fire of 1900 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Chinatown, Honolulu, Hawaii |

| Statistics | |

| Date(s) | January 20-February 6, 1900 |

| Burned area | 38 acres (150,000 m2) |

| Land use | urban |

| Fatalities | 1 in honolulu, 9 on maui (all from plague) |

From witnesses a wave of bubonic plague was introduced to Honolulu on October 20, 1899 by an off loaded shipment of rice which had been carrying rats from the America Maru. At that time, Chinese immigration to Hawaii resulted in a crowded residential area called Chinatown with poor living conditions and sewage disposal. Plague infected 11 people. The response by the Board of Health included incinerating garbage, renovating the sewer system, putting Chinatown under quarantine, and most of all burning infected buildings. 41 fires were set, but on January 20, 1900 winds picked up and the fire spread to other buildings which was undesired.[13] The runaway fire burned for seventeen days and scorched 38 acres (15 Ha) of Honolulu. The fire campaign continued for another 31 controlled burns after the incident. The 7,000 homeless residents were housed in detention camps to maintain the quarantine until April 30. A total of 40 people died of the plague.

Critics accused the government of being driven by Sinophobia; regardless of the fire most likely being an accident, an exodus occurred. While the people rebuilt, they began to live in suburbs while continuing to work in Chinatown, to avoid going homeless if another disaster occurred. In addition the post-fire architecture began using masonry rather than wood, since the stone and brick buildings proved much more fire resistant during the fire.

Many of the people who filed damage claims were represented by lawyer Paul Neumann (not to be confused with the actor), but he died before the cases went to court.[14]

Preservation

After World War II the area fell into disrepair and became a red-light district.[15] About 36 acres (15 ha) of the district was added to the National Register of Historic Places listings in Oahu on January 17, 1973 as site 73000658.[1] During the administrations of mayors Frank Fasi and Jeremy Harris the area was targeted for revitalization. Restrictions on lighting and signs were relaxed to promote nightlife.[15] Special zoning rules were adopted for the area.[16] The Hawaii National Bank was founded in the district in 1960, and has its headquarters there.[17]

On the eastern edge of the district, the Hawaii Theatre was restored and re-opened in 1996.[18] The area around the theatre is called the Arts District. In 2005 a small park near the theatre at the corner of Hotel and Bethel streets was opened and called Chinatown Gateway Park.[19] In November 2007 the park was named in honor of Sun Yat-Sen who came to Chinatown in 1879 where he was educated and planned the Chinese Revolution of 1911.[20] Honolulu Chinatown was included in the Preserve America program.[21]

Government and infrastructure

The Downtown Police Substation of the Honolulu Police Department is located in Chinatown.[22] Officials broke ground for the substation on Friday September 18, 1998. Mayor Jeremy Harris said that he wanted a police station built at that location because of crime had been occurring in that area, and the presence of a police station would deter crime.[23]

Popular culture

The character Charlie Chan was based on detective Chang Apana (1871–1933). Earl Derr Biggers read about Apana and based the character in Honolulu after a vacation in 1919.[24] The character Wo Fat in the TV series Hawaii Five-O was named after a restaurant in Honolulu's Chinatown. The business first opened in 1882, but the building was destroyed in the 1886 fire. A new building was built after the 1900 fire, and then another in 1932. It was located at 115 North Hotel Street, 21°18′44.4″N 157°51′47″W / 21.312333°N 157.86306°W.[25] The Wo Fat Restaurant closed in 2005,[26] and the building housed a nightclub in the early 2000s.[27]

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Richard A. Greer (1998). "Along the Old Honolulu Waterfront". Hawaiian Journal of History. 32. Hawaii Historical Society. pp. 53–66. hdl:10524/430.

- ↑ Mary Kawena Pukui and Elbert (2004). "lookup of vineyard". on Place Names of Hawai'i. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- 1 2 Dorothy Riconda (May 2, 1972). "Chinatown Historic District nomination form". National Register of Historic Places. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ "Honolulu Responds to the Plague". Hawaii state historic preservation division. 2002. Retrieved 2010-04-08.

- ↑ Michael Tsai (July 2, 2006). "Bubonic plague and the Chinatown fire". Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ↑ Mary Kawena Pukui and Elbert (2004). "lookup of Beretania". on Place Names of Hawai'i. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ http://papakilodatabase.com/pdnupepa/cgi-bin/pdnupepa?a=d&d=KNK19000406-01.2.9&srpos=7&dliv=none&e=01-01-1899-31-12-1900--en-20--1--txt-txIN%7ctxNU%7ctxTR-pauahi------

- ↑ Burl Burlingame (December 14, 2003). "Efficient design and perfect location define market". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- 1 2 Mohr, J. C. (2006). Plague and fire: battling Black Death and the 1900 burning of Honolulus Chinatown. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 "Public Health Reports". U.S Marine Hospital Service. 15: 1–26.

- 1 2 3 Ikeda, James K. "A Brief History of Bubonic Plague in Hawaii" (PDF). Hawaiian Entomological Society. 25.

- ↑ www.hawaiiforvisitors.com

- ↑ "Local and General News: The Last Ceremony". The Independent. Honolulu. July 3, 1901. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- 1 2 Peter Wagner (September 29, 1998). "Chinatown: A bike city waiting to be reborn". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ "Chinatown Special District Design guidelines" (PDF). City and County of Honolulu. April 1991. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ "Hawaii National Bank". official web site. 2009. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ "Hawaii Theatre Center: History". web site. Archived from the original on 2010-09-20. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ "Mayor Announces Reopening Of Chinatown Gateway Park". The City and County of Honolulu. November 5, 2005. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ "City to Dedicate Statue and Rename Park to Honor Dr. Sun Yat-Sen". The City and County of Honolulu. November 12, 2007. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ "Preserve America Community: Chinatown Special Historic District, Honolulu, Hawaii". April 21, 2009. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ "Contacting HPD Archived 2010-05-31 at the Wayback Machine.." Honolulu Police Department. Retrieved on May 19, 2010.

- ↑ Constantino, Stan. "New era in crime fight begins in Chinatown." Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Saturday September 19, 1998. Retrieved on May 19, 2010.

- ↑ Jaymes K. Song (October 2, 1999). "'Charlie Chan' isle's toughest crime fighter". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ Burl Burlingame (December 28, 2003). "Like a phoenix, Wo Fat always rises". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ Sigall, Bo (March 2, 2012). "Wo Fat Restaurant Lives on as Name of 'Five-0' Villain". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved 2014-07-14.

- ↑ Daniel Gray. "The Loft Gallery and Lounge". web site. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

Further reading

- James C. Mohr (2005). Plague and fire: battling black death and the 1900 burning of Honolulu's Chinatown. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-516231-8.

External links

- "Honolulu's Chinatown". community web site. Archived from the original on 2010-01-27. Retrieved 2010-04-09.