Bhimsen Thapa

| Sri Mukhtiyar General Saheb Bhimsen Thapa | |

|---|---|

|

श्री मुख्तियार जर्नेल साहेब भीमसेन थापा | |

Bhimsen Thapa, the Mukhtiyar (equivalent to Prime Minister) of Nepal from 1806 to 1837 | |

| Mukhtiyar of Nepal | |

|

In office 1806–1837 | |

| Monarch |

Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah Rajendra Bikram Shah |

| Preceded by |

Rana Bahadur Shah as Mukhtiyar |

| Succeeded by | Rana Jang Pande |

| Commander-in-Chief | |

| Preceded by | Damodar Pande |

| Succeeded by | Rana Jang Pande |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

August 1775 Pipal Thok village, Phinam VDC, Gorkha district, Nepal |

| Died |

5 August 1839 (aged 64) Bhim-Mukteshwar, bank of Bishnumati River, Kathmandu, Nepal |

| Nationality | Nepali |

| Relations |

Nain Singh Thapa (brother) Ambika Devi Kunwar (sister) Bhaktabar Singh Thapa (brother) Ranabir Singh Thapa (brother) Balbhadra Kunwar (nephew) Queen Tripurasundari of Nepal (niece) Ujir Singh Thapa (nephew) Mathabarsingh Thapa (nephew) Jung Bahadur Rana (grand-nephew) Ranodip Singh Kunwar (grand-nephew) |

| Children |

Lalita Devi Pande Janak Kumari Pande Dirgha Kumari Pande[1] |

| Mother | Satyarupa Maya |

| Father | Amar Singh Thapa (sanukaji) |

| Residence | Thapathali Durbar (1798–1804), Bag Durbar (1804–1837)[2] |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | Bhimsen Kaji, Thapa Kaji |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | Nepal Army |

| Years of service | 1798–1837 |

| Rank | Commander-in-Chief |

| Commands | Commander-in-Chief |

| Battles/wars | Anglo-Nepalese War |

Bhimsen Thapa ![]()

Bhimsen rose to power by initially serving as a bodyguard and personal secretary of King Rana Bahadur Shah. Bhimsen had accompanied Rana Bahadur Shah to Varanasi after his abdication and subsequent exile in 1800. In Varanasi, Bhimsen helped Rana Bahadur engineer his return to power in 1804. In gratitude, Rana Bahadur made Bhimsen a Kaji (equivalent to a minister) of the newly formed government. Rana Bahadur's assassination by his step-brother in 1806 led Bhimsen to massacre ninety-three people, after which he was able to claim the title of the Mukhtiyar (equivalent to prime minister) and put forward Thapa family in the national politics putting check and balance on the historical noble Pande dynasty of Gorkha.

Bhimsen introduced a large number of reforms in agriculture, forestry, trade and commerce, judiciary, military, communications, transportations, slavery, human trafficking and other social evils in his premiership. During Bhimsen's prime ministership, the Gurkha empire had reached its greatest expanse from Sutlej river in the west to the Teesta river in the east. However, Nepal entered into a disastrous Anglo-Nepalese War with the East India Company lasting from 1814–16, which was concluded with the Treaty of Sugauli, by which Nepal lost almost one-third of its land. It also led to the establishment of a permanent British Residency. The death of King Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah in 1816 before his maturity, and the immature age of his heir, King Rajendra Bikram Shah, coupled with the support from Queen Tripurasundari (the junior queen of Rana Bahadur Shah) allowed him to continue to remain in power even after Nepal's defeat in the Anglo-Nepalese War.

The death of Queen Tripurasundari in 1832, his strongest supporter, and the adulthood of King Rajendra, weakened his hold on power. The conspiracies and infighting with rival courtiers (especially the Pandes, who held Bhimsen Thapa responsible for the death of Damodar Pande in 1804) finally led to his imprisonment and death by suicide in 1839. However, the court infighting did not subside with his death, and the political instability eventually paved way for the establishment of the Rana dynasty.

Early years

Bhimsen Thapa was born in August 1775 at Pipal Thok village of Gorkha district, to father Amar Singh Thapa(sanu)[note 2] and mother Satyarupa Maya.[4] He belonged to a Chhetri family of Bharadars (courtiers).[5] His ancestors were members of Bagale Thapa clan from Jumla who migrated eastwards.[4][6] His grandfather was Bir Bhadra Thapa, a courtier in Prithvi Narayan Shah's army.[4] Bhimsen Thapa had four brothers—Nain Singh Thapa, Bhaktabar Singh Thapa, Amrit Singh Thapa, and Ranabir Singh Thapa.[7][8] From his step-mother, he had two brothers—Ranbam and Ranzawar.[8] While it is not certain when Bhimsen got married, he had three wives with whom he begot one son, that died at an early age in 1796, and three daughters – Lalita Devi, Janak Kumari and Dirgha Kumari. Lack of a son caused him to adopt Sher Jung Thapa, son of his brother Nain Singh Thapa.[8]

Not much detail is known about Bhimsen Thapa's early life. At the age of 11, Bhimsen came into contact with the Nepalese Royal Palace when his Bratabandha (sacred thread) ceremony was held together with the Crown Prince Rana Bahadur Shah in Gorkha in 1785.[9][8] In 1798, his father took him to Kathmandu and enrolled him as a bodyguard to the king.[8] In Kathmandu, Bhimsen took up residence at Thapathali Durbar, after which he lived in Bagh Durbar near Tundikhel after becoming a kaji (equivalent to a minister).[8]

Rise to power: 1798–1804

_LACMA_M.76.129.jpg)

Royal household

The premature death of Pratap Singh Shah (reigned 1775–77), the eldest son of Prithvi Narayan Shah, left a huge power vacuum that remained unfilled, seriously debilitating the emerging Nepalese state. Pratap Singh Shah's successor was his son, Rana Bahadur Shah (reigned 1777–99), aged two and one-half years at his accession.[9] The acting regent until 1785 was Queen Rajendralakshmi, followed by Bahadur Shah (reigned 1785–94), the second son of Prithvi Narayan Shah.[10] Court life was consumed by rivalry centered on alignments with these two regents rather than on issues of national administration, and it set a bad precedent for future competition among contending regents. The exigencies of Sino-Nepalese War in 1788–92 had forced Bahadur Shah to temporarily take a pro-British stance, which had led to a commercial treaty with the British in 1792.[11]

Meanwhile, Rana Bahadur Shah's youth had been spent in pampered luxury. In 1794 Rana Bahadur came of age, and his first act was to re-constitute the government, with his uncle, Bahadur Shah, removed from all official position.[12][13] In mid-1795, he became infatuated with a Maithili Brahman widow, Kantavati Jha, and married her on the oath of making their illegitimate half-caste son (as per the Hindu law of that time) the heir apparent, by excluding the legitimate heir from his previous marriage.[note 3][13][15] By 1797, his relationship with his uncle, who was living a retired life, and who wanted to seek refuge in China on the pretext of meeting the new emperor, had deteriorated to the extent that he ordered his imprisonment on 19 February 1797 and his subsequent murder on 23 June 1797. Such acts earned Rana Bahadur notoriety both among courtiers and common people, especially among Brahmins.[13][16]

That same year in 1797, Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah was born and was hastily declared the crown prince.[17] However, within a year of Girvan's birth, Kantavati contracted tuberculosis; and it was advised by physicians that she perform ascetic penances to cure herself. To make sure that Girvan succeeded to the throne while Kantavati was still alive, Rana Bahadur, aged just 23, abdicated in favor of their son on 23 March 1799, placing his first wife, Rajrajeshwori, as the regent.[17] He joined his ailing wife, Kantavati, with his second wife, Subarnaprabha in ascetic life and started living in Deopatan, donning saffron robes and titling himself Swami Nirgunanda.[note 4] This move was also supported by all the courtiers who were discontented with his wanton and capricious behavior.[13][17] It was around this time that both Bhimsen Thapa and his father Amar Singh Thapa (sanu) were promoted from Subedar to the rank of Sardar, and Bhimsen began to serve as the ex-King's chief bodyguard.[19] However, Rana Bahadur's renunciation lasted only a few months. After the inevitable death of Kantavati, Rana Bahadur suffered a mental breakdown during which he lashed out by desecrating temples and cruelly punishing the attendant physicians and astrologers.[20] He then renounced his ascetic life and attempted to re-assert his royal authority.[21] This led to a direct conflict with almost all the courtiers who had pledged a holy oath of allegiance to the legitimate King Girvan; this conflict eventually led to the establishment of a dual government and to an imminent civil war, with Damodar Pande leading the military force against the dissenting ex-King and his group.[22][21] Since most of the military officers had sided with the courtiers, Rana Bahadur realized that his authority could not be re-established; and he was forced to flee to the British-controlled city of Varanasi in May, 1800.[22][21]

Exile in Varanasi: 1800–1804

As Rana Bahadur Shah's bodyguard and advisor, Bhimsen Thapa also accompanied him to Varanasi. Rana Bahadur's retinue included his first wife, Raj Rajeshwari Devi, while his second wife, Subarna Prabha Devi, stayed back in Kathmandu to serve as the regent.[23] Since Rana Bahadur was willing to do anything to regain his power and punish those who had forced him to exile, he served as a focal point of dissidenting factions in Varanasi. In November 1800, he first sought help from the British in exchange for which he was willing to concede a trading post in Kathmandu and grant them 37.5% of the tax revenue derived from the hills and 50% from the Terai.[22][24] However, the British were in favor of working with the existing government in Nepal, rather than risk the uncertainties of restoring an exiled ex-King to power.[25][26] The Kathmandu Durbar was willing to appease the British and agreed to sign a commercial treaty so long as the wayward Rana Bahadur and his group were held in India under strict British surveillance.[25][27] This arrangement was kept a secret from Rana Bahadur and his group; but when they eventually became aware of the strictures on their movement, and hence the treaty, they were incensed at the British as well as the proponents (Damodar Pande and his faction) of this treaty in Nepal.[26] An intrigue was set in motion with the aim of splitting the unity of courtiers in Kathmandu Durbar and fomenting anti-British feelings. A flurry of letters were exchanged between the ex-King and individual courtiers in which he tried to set them up against Damodar Pande and tried to woo them by promises of high government positions, which they could hold for their entire life, and which could be inherited by their progeny.[28][29] Baburam Acharya holds Bhimsen responsible for all these schemes, reasoning that Rana Bahadur did not have the mental capacity for such negotiations and intrigues. He contends that Bhimsen was responsible for negotiation with the British as well as responsible for writing letters in the name of the ex-King, while the ex-King was bidding his time in debauchery.[28]

Meanwhile, Rajrajeshowri, fed up with her debauch husband, left Varanasi,[note 5] entered the border of Nepal on 26 July 1801, and taking advantage of the weak regency, was slowly making her way towards Kathmandu with the view of taking over the regency. [31][32] Back in Kathmandu the court politics turned complicated when Mul Kaji (or chief minister) Kirtiman Singh Basnyat, a favorite of the Regent Subarnaprabha, was secretly assassinated on 28 September 1801, by the supporters of Rajrajeswori.[27] In the resulting confusion, many courtiers were jailed, while some executed, based solely on rumors. Bakhtawar Singh Basnyat, brother of assassinated Kirtiman Singh, was then given the post of Mulkaji[33] During his tenure as the Mul Kaji, on 28 October 1801, a Treaty of Commerce and Alliance[note 6] was finally signed between Nepal and East India Company. This led to the establishment of the first British Resident, Captain William O. Knox, who was reluctantly welcomed by the courtiers in Kathmandu on 16 April 1802.[note 7][39] The primary objective of Knox's mission was to bring the trade treaty of 1792 into full effect and to establish a "controlling influence" in Nepali politics.[34] Almost eight months after the establishment of the Residency, Rajrajeshwari finally managed to assume the regency on 17 December 1802.[25][32]

Return to Kathmandu

After Rajrajeshwori took over the regency, she was pressured by Knox to pay the annual pension of 82,000 rupees to the ex-King as per the obligations of the treaty,[34] which paid off the vast debt that Rana Bahadur Shah had accumulated in Varanasi due to his spendthrift habits.[note 8][25][42][40] The Nepalese court also felt it prudent to keep Rana Bahadur in isolation in Nepal itself, rather than in the British controlled India, and that paying off Rana Bahadur's debts could facilitate his return at an opportune moment.[42] Rajrajeshwari's presence in Kathmandu also stirred unrest among the courtiers that aligned themselves around her and Subarnaprabha. Sensing an imminent hostility, Knox aligned himself with Subarnaprabha and attempted to interfere with the internal politics of Nepal.[43] Getting a wind of this matter, Rajrajeshwari dissolved the government and elected new ministers, with Damodar Pande as the Mulkaji, while the Resident Knox, finding himself persona non grata and the objectives of his mission frustrated, voluntarily left Kathmandu to reside in Makwanpur citing a cholera epidemic.[43][34] Subarnaprabha and the members of her faction were arrested.[43]

Such open display of anti-British feelings and humiliation prompted the Governor General of the time Richard Wellesley to recall Knox to India and unilaterally suspend the diplomatic ties.[44] The Treaty of 1801 was also unilaterally annulled by the British on 24 January 1804.[34][45][46][44] The suspension of diplomatic ties also gave the Governor General a pretext to allow the ex-King Rana Bahadur to return to Nepal unconditionally.[45][44]

As soon as they received the news, Rana Bahadur and his group proceeded towards Kathmandu. Some troops were sent by Kathmandu Durbar to check their progress, but the troops changed their allegiance when they came face to face with the ex-King.[47] Damodar Pande and his men were arrested at Thankot where they were waiting to greet the ex-King with state honors and take him into isolation.[47][46] After Rana Bahadur's reinstatement to power, he started to extract vengeance on those who had tried to keep him in exile.[48] He exiled Rajrajeshwari to Helambu, where she became a Buddhist nun, on the charge of siding with Damodar Pande and colluding with the British.[49][50] Damodar Pande, along with his two eldest sons, who were completely innocent, was executed on 13 March 1804; similarly some members of his faction were tortured and executed without any due trial, while many others managed to escape to India.[note 9][51][50] Rana Bahadur also punished those who did not help him while in exile. Among them was Prithvipal Sen, the king of Palpa, who was tricked into imprisonment, while his kingdom forcefully annexed.[52][53] Subarnaprabha and her supporters were released and given a general pardon. Those who had helped Rana Bahadur to return to Kathmandu were lavished with rank, land, and wealth. Bhimsen Thapa was made a second kaji; Ranajit Pande, who was the father-in-law of Bhimsen's brother, was made the Mulkaji; Sher Bahadur Shah, Rana Bahadur's half-brother, was made the Mul Chautariya; while Rangnath Paudel was made the Raj Guru (royal spiritual preceptor).[52][54]

As Kaji: 1804–1806

Baisathi Haran

After the power shuffle, in 1805, Bhimsen became the architect of an unpopular plan of seizing all the tax free land granted to temple guthis and as birta to Brahmin priests in order to fill the empty state coffers.[55][56][note 10] The objective was to scrutinize the cases in which tax-exempt lands had been used without valid documentary proof of land grant by a benefactor; owners with valid evidence or owners who could take an oath of validity were not affected.[58] The money was spent in financing the military campaigns in the far west in Jamuna-Sutlej region. This was a very radical reform in the staunchly religious society of the time and became known as Baisathi Haran in the Nepalese history.[55][56]

Bhandarkhal massacre of 1806

After returning to Kathmandu, in complicity with Rana Bahadur, Bhimsen indulged in appropriating the palaces and properties of deposed members of Shah family,[note 11] which he shared between himself and his supporter Rangnath Paudel.[59] This aroused resentment and jealousy among Sher Bahadur Shah (Rana Bahadur's step-brother) and his faction, since they did not receive any portion of this confiscated property, despite their help in reinstating Rana Bahadur to power.[note 12][62] They were also wary of Bhimsen's growing power.[60] By this time, Rana Bahadur was a nominal figure and Kaji Bhimsen Thapa was single-handedly controlling the central administration of the country, being able to implement even unpopular reforms like Baisathi Haran.[63]

Bhimsen felt the need to finish off his rivals, but at the same time, felt a need to take precaution before going after immediate members of the royal household. For almost two years after returning to Kathmandu, Rana Bahadur had no official position in the government – he was neither a king, nor a regent, nor a minister – yet he felt no qualms in using the full state power.[63] Not only did Rana Bahadur carry out the Baisathi Haran under Bhimsen's advice, he was also able to banish all non-vaccinated children, as well as their parents, from the town during a smallpox outbreak, in order to prevent King Girvan from catching that disease.[64] Now, after almost two-year, all of a sudden Rana Bahadur was made Mukhtiyar (chief authority) and Bhimsen tried to implement his schemes through Rana Bahadur.[65] Bhimsen had also secretly learned of a plot to oust Rana Bahadur.[66] Tribhuvan Khawas (Pradhan), a member of Sher Bahadur's faction, was imprisoned on the re-opened charges of conspiracy with the British that led to the Knox's mission, but for which pardon had already been doled out, and was ordered to be executed.[64][67] Tribhuvan Khawas decided to reveal everyone that was involved in the dialogue with the British.[64][67] Among those implicated was Sher Bahadur Shah.[64][67]

On the night of 25 April 1806, Rana Bahadur held a meeting at Tribhuvan Khawas's house with rest of the courtiers, during which he taunted and threatened to execute Sher Bahadur.[68][69] At around 10 pm, Sher Bahadur in desperation drew a sword and killed Rana Bahadur Shah before being cut down by nearby courtiers, Bam Shah and Bal Narsingh Kunwar, also allies of Bhimsen.[70][71] The assassination of Rana Bahadur Shah triggered a great massacre in Bhandarkhal (a royal garden east of Kathmandu Durbar) and at the bank of Bishnumati river.[72][73] That very night members of Sher Bahadur's faction – Bidur Shah, Tribhuvan Khawas, and Narsingh Gurung – and even King Prithvipal Sen of Palpa, who was under house arrest in Patan Durbar, were swiftly rounded up and killed in Bhandarkhal.[74][75] Their dead bodies were not allowed funeral rites and were dragged and thrown by the banks of Bishnumati to be eaten by vultures and jackals.[74][75] The next few days, all the sons of Sher Bahadur Shah, Bidur Shah, Tribhuvan Khawas and Narsingh Gurung, aged 2 to 15 were beheaded by the bank of Bishnumati; their wives and daughters were given to the untouchables, their bodyguards and servants were also put to death, and all their property seized.[74][73] Bhimsen managed to kill everyone who did not agree with him or anyone who could potentially become a problem for him in the future. In this massacre that lasted for about two weeks, a total of ninety-three people (16 women and 77 men) lost their lives.[74][76]

Almost one and half months before the massacre, upon Bhimsen's insistence, Rana Bahadur, then 31 years old, had married a 14-year-old girl named Tripurasundari on 7 March 1806, making her his fifth legitimate wife.[note 13][78] Taking advantage of the political chaos, Bhimsen became the Mukhtiyar (1806–37), and Tripurasundari was given the title Lalita Tripurasundari and declared regent and Queen Mother (1806–32) of Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah, who was himself 9 years old.[79] Thus, Bhimsen became the first person outside the royal household to hold the position of the Mukhtiyar. All the other wives (except Subarnaprabha[80]) and concubines of Rana Bahadur, along with their handmaidens, were forced to commit sati.[76][81] Bhimsen obtained a royal mandate from Tripurasundari, given in the name of King Girvan, commanding all other courtiers to be obedient to him.[79] Bhimsen further consolidated his power by disenfranchising the old courtiers from the central power by placing them as administrators of far-flung provinces of the country. The courtiers were instead replaced by his close relatives, who were mere yes-men.[82] On the spot where Rana Bahadur Shah drew his last breath, Bhimsen later built a commemorative Shiva temple by the name Rana-Mukteshwar.[83]

As Mukhtiyar: 1806–1832

Expansion in the West

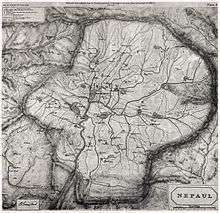

By the time Bhimsen came to power, the territory of Nepal extended up to the border of Garhwal in the west. During the reign of Bahadur Shah, Nepal had concluded a treaty with Garhwal demanding that it pay NRs. 9,000 per year. Later Rana Bahadur Shah reduced it to NRs. 3,000. However, in 1804, Garhwal refused to pay the amount upon which Bhimsen sent an army under the command of Bada Kaji Amar Singh Thapa (not to be confused with his father), Bhakti Thapa and Hasti Dal Shah to attack Garhwal.[84] The army succeeded in annexing Garhwal to Nepalese territory extending the territory of Nepal up to the Sutlej river in the west.[85] After the annexation of Garhwal, the Nepalese army attacked the fort of Kangra but was defeated by the combined army of Sansar Chand, the ruler of Kangra, and that of Ranjit Singh, the ruler of Punjab.[86] Other states like Salyan were also annexed to Nepal during his rule. Before the Anglo-Nepalese War, the territory of Nepal extended from Sutlej river in the west to Teesta river in the east. Most of this territory, however, was lost in the Anglo-Nepalese War.[86] In 1811, Bhimsen was given the title of General, thus enjoying a dual position of Mukhtiyar and General.[87]

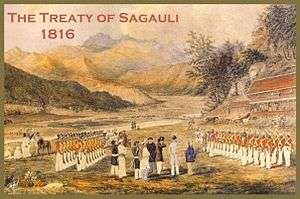

Anglo-Nepalese War: 1814–1816

The Anglo–Nepalese War (1814–1816), sometimes called the Gorkha War, was fought between Nepal and the British East India Company as a result of border tensions, trade dispute, and ambitious expansionism of both the belligerent parties. While the immediate reason for the war was the border dispute in the terai region, the hostility between the two parties had been brewing for more than a decade since the failure of Knox's mission.[88] This war was the most important event during the mukhtiyari of Bhimsen Thapa since it affected every aspect of the later course of Nepalese history. Considering the many successes that the Nepalese army had seen during the expansion campaign of Nepal, Bhimsen Thapa was one of the main proponents of the war with the British, which was against the better advice of the likes of Bada Kaji Amar Singh Thapa, who actually did the fighting and knew about the hardships of war.[89][90] Bhimsen's attitude before the war is summarized in the following letter to King Girvan, where we can find a hint of superstition on Nepalese invincibility:

Through the influence of your good fortune, and that of your ancestors, no one has yet been able to cope with the state of Nipal. The Chinese once made war upon us, but were reduced to seek peace. How then will the English be able to penetrate into the hills? Under your auspices, we shall by our own exertions be able to oppose to them a force of fifty-two lakhs of men, with which we will expel them. The small fort of Bhurtpoor was the work of man, yet the English being worsted before it, desisted from the attempt to conquer it; our hills and fastnesses are formed by the hand of God, and are impregnable. I therefore recommend the prosecution of hostilities. We can make peace afterwards on such terms as may suit our convenience.[91]

The British launched two successive waves of invasion campaigns. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Sugauli in 1816, which ceded around one-third of Nepal's territory to the British. Furthermore, according to the treaty, Nepal had to allow for the establishment of a permanent British resident in Kathmandu and had to forgo all self-determination in foreign affairs. During the war, Bhimsen Thapa served as the Commander-in-Chief of the Nepalese army; and thus he had to bear the direct responsibility of Nepalese defeat.[92][93]

Hold on power

In May 1816, Edward Gardner arrived in Kathmandu as the first British Resident after the conclusion of the Treaty of Sugauli. Bhimsen used all his influence to cultivate peace, although not friendliness, with the British, "a Power," as he said, "that crushed thrones like potsherds."[94] His foreign policy after the war was essentially the one handed down by Prithvi Narayan Shah – to keep Nepal isolated from any foreign influences. As such, although he was forced to accept a British resident in Kathmandu as per the Treaty of Sugauli, he made sure to cut off the resident from all contacts with life in Nepal to the point of making the Resident a virtual prisoner. Apart from petty harassment, the Resident was only allowed to travel within the Kathmandu valley, that too only with special escorts. The resident was also barred from meeting the king or any courtiers at will. Thus the threat of having a Resident in Kathmandu was not as keen as had been anticipated.[95]

On 20 November 1816, King Girvan Yuddha died of smallpox, aged nineteen.[96] Girvan had two wives – the first wife committed sati with Girvan, while the second wife also died of smallpox after 14 days of Girvan's death. Thus, Girvan was succeeded by his only son, Rajendra Bikram Shah, an infant of two years old, after 18 days of his father's death on 8 December 1816. Therefore, Bhimsen Thapa, in collusion with the queen regent, Tripurasundari, remained in power despite the defeat of Nepal in the Anglo-Nepalese War of 1814–16.[97] There was a sustained opposition against Bhimsen from factions centered around leading members of other aristocratic families, notably the Pandes,[note 14] who denounced what they felt was his cowardly submission to the British. Paradoxically, the peacetime after the Anglo-Nepalese War saw the inflation and modernization of the Nepal army, which Bhimsen used to keep his opposition under control,[99] while at the same time convincing the suspicious British that he had no intention of using it against them. Bhimsen appointed his own family members and his most trusted men to the highest positions at the court and in the army, while members of older aristocratic families were made administrators of far-flung provinces of the kingdom, away from the capital.[100]

Thus, Bhimsen was able to continue making all the administrative decisions of the country, while the Regent Queen Tripurasundari would unquestioningly approve these decisions by stamping the royal seal issued in the name of King Rajendra on these government orders. The Regent never dared to express any doubts regarding Bhimsen's decisions.[101] Nevertheless, to make sure that the King, his wives – Samrajya Laxmi Devi (senior) and Rajya Lakshmi Devi (junior) – and the Regent were insulated from influences of people other than Bhimsen and his closest relatives, Bhimsen had instated his youngest brother, General Ranvir Singh Thapa, in the royal palace to keep a watch on the royal family and to keep guard against any outside person.[102] Any priest or courtier who wished to be granted an interview with the King, the Queens, or the Regent, had to get an approval from Ranbir Singh and the interview had to be conducted under his watchful presence.[102] Similarly, the royal family were not allowed to leave the palace without Bhimsen's permission either. Bhimsen had also neglected the formal education of Rajendra, due to which he had grown to be uncritical and weak minded to the extent that he was even unaware that he was virtually a prisoner.[102] However, his wives were more alert and wary of Bhimsen since, according to Baburam Acharya, they received unfiltered news of the world outside the royal palace from their handmaidens, who would leave the palace compounds and go to their homes during their menstruation and gather news and rumors of the day, which they would then relate to the Queens.[103]

Infighting

_LACMA_M.91.206.jpg)

Reasons

The Gorkha aristocracy had led Nepal into a disaster on the international front but preserved the political unity of the country, which at the end of the Anglo-Nepalese War in 1816 still was only about twenty-five years old as a unified nation. The success of the central government rested in part on its ability to appoint and control regional administrators, who also were high officers in the army. In theory, these officials had great local powers; in practice they spent little energy on the daily affairs of their subjects, interfering only when communities could not cope with problems or conflicts. Another reason for Gorkha success in uniting the country was the willingness to placate local leaders by preserving areas where former kings and communal assemblies continued to rule under the loose supervision of Kathmandu, leaving substantial parts of the country out of the control of regional administrators. Even within the areas directly administered by the central government, agricultural lands were given away as jagir to the armed services and as birta to court favorites and retired servicemen.[note 10] The holder of such grants in effect became the lord of the peasants working there, with little if any state interference.[104] From the standpoint of the average cultivator, the government remained a distant force, and the main authority figure was the landlord, who took part of the harvest, or (especially in the Tarai) the tax collector, who was often a private individual contracted to extort money or crops in return for a share.[105] For the leaders in the administration and the army, as military options became limited and alternative sources of employment grew very slowly, career advancement depended less on attention to local conditions than on loyalty to factions fighting at court.[106]

Actors

Five leading families or factions contended for power during this period—the Shahas, Thapas, Basnyats, Pandes, and the Chautariyas, who were of Shah dynasty but acted as counselors for the King. Working for these families and their factions were hill Brahmans, who acted as religious preceptors or astrologers, and Newars, who occupied secondary administrative positions. No one else in the country had any influence on the central government. When a family or faction achieved power, it killed, exiled, or demoted members of opposing alliances. Under these circumstances, there was little opportunity for either public political life or coordinated economic development.[106][107]

Consequences

The struggle for power at the court had unfortunate consequences for both foreign affairs and for internal administration. All parties tried to satisfy the army in order to avoid interference in court affairs by leading commanders, and the military was given a free hand to pursue ever larger conquests. As long as the Gorkhas were invading disunited hill states, this policy—or lack of policy—was adequate. Inevitably, continued aggression led Nepal into disastrous collisions with the Chinese and then with the British. At home, because power struggles centered on control of the king, there was little progress in sorting out procedures for sharing power or expanding representative institutions. A consultative body of nobles, a royal court called the Assembly of Lords (Bharadari Sabha), was in place after 1770 and it had substantial involvement in major policy issues. The assembly consisted of high government officials and leading courtiers, all heads of important Gorkha families. In the intense atmosphere surrounding the monarch, however, the Assembly of Lords broke into factions that fought for access to the prime minister or regent, and alliances developed around patron/client relationships.[106][108]

Downfall: 1832–1838

Death of Queen Tripurasundari

The power balance began to change after King Rajendra came of age and his grandmother, Tripurasundari, died on 26 March 1832 due to cholera.[109][110] Bhimsen lost his main support and the court became a stage for a power struggle, which even though started off as an attempt to assert the King's authority from the Mukhtiyar, spread to various aristocratic clans and their attempt to secure total authority.[111] It was no secret that Bhimsen was able to maintain his supremacy due to the large standing army under his and his family's command; and in the subsequent years, different factions would attempt to increase their influence based on the strength of the number of battalions under their grip.[111] After Tripurasundari's death, the royal seal by which government orders were approved naturally went into the hands of the senior queen Samrajya Laxmi, who knew all too well of its powers and wanted to emulate the queens of the past by establishing her own regency.[110][112] Sensing Samrajya Laxmi's ambition, Ranbir Singh started to stroke her dislike of Bhimsen in the hopes of becoming the Mukhtiyar himself.[110] There was a quarrel between Mathabar Singh Thapa and Ranabir Singh regarding the latter's loyalty shift towards the senior Queen Samrajya Lakshmi resulting in Mathabar resigning from the commandership of Sri Nath Regiment.[113] Getting a whiff of this matter, Bhimsen strongly reprimanded Ranbir Singh which caused him to resign from his General's position and live in retirement in his house at Sipamandan.[114] However, Bhimsen later managed to placate his brother, by giving him the title of Chota (Little) General, and send him to Palpa as its governor.[115][116] To counter the opposition arising in Darbar after the incident, he appointed young Kaji Surath Singh Thapa, a grandson of Bada Kaji Amar Singh Thapa to a very high administrative position in the Darbar and made him joint chief signatory.[116] Since he could find nobody that he could trust to keep watch over the royal palace, Bhimsen from then on started to live in an ordinary rented house located near the palace premise.[117]

Sharing of administrative duties

Initially, King Rajendra supported Bhimsen instead of Ranabir Singh and the removal of Ranabir Singh sabotaged the Queen's plan.[116] King Rajendra appointed Bhimsen to the post of Commander-in-Chief and praised Bhimsen for long service to the nation.[118] Queen Samrajya Laxmi harassed King Rajendra;

You are an independent Raja indeed. You are a slave of Bhim Sen Thapa.... a sheep led to the slaughter. Has he bewitch you or has he poured lead into your ears rendering you deaf. Let me and my children leave you to the fate your imbecility deserve, or ...you become religious and go to Benaras to bath and pray and leave me without the eldest boy to rule the country and try if a women can succeed where a man has failed in annihilating the Thapas and asserting the lawful rights of sovereignty among her people.[118]

The King and the Queens also started to openly challenge Bhimsen's authority. By this time, Rajendra and his wives had heard the widespread rumor that Bhimsen, in order to remain in power, had killed the late King Girvan and his wives by administering poison a few days after Girvan's coming off age. So when Rajendra was afflicted by an ordinary illness, the Queens cautioned the King and prohibited him to take the medicine offered by the royal physician, Sardar Ekdev Upadhyay, who was loyal to Bhimsen.[117] Similarly, during the annual muster of 1833, during which the civil and military officers were promoted, renewed, retained, or retired, everything was conducted according to Bhimsen's plan, but Rajendra delayed the retainment of Bhimsen's own position as the Mukhtiyar.[117]

This forced Bhimsen to share the administrative burden between Rajendra, Samrajya Laxmi, and himself, and ask for their opinions on administrative matters, in order to reduce further friction between himself and the royalty. Rajendra was put in charge of defense, finance, and foreign relations; while Samrajya Laxmi was put in charge of justice, accountancy, and civil administration.[119] Nevertheless, Rajendra's activities were heavily influenced by the advice of Samrajya Laxmi, while the Junior Queen Rajya Laxmi had no say in any matter; furthermore, the King and the Senior Queen did not dare yet to outright dismiss Bhimsen's plans and advice, fearful of the large army under his command.[119] This arrangement worked well for the next three years; for instance, on 26 August 1833, Nepal was struck by a great earthquake,[120] and all three power holders were able to coordinate with each other and provide emergency relief to the citizens.[119][note 15]

Failure of Mathabar Singh Thapa's mission to Britain

That same year, Brian Hodgson, who had spent many years in Nepal serving as the Assistant Resident, and who had a good knowledge about Nepal's biodiversity, culture, and politics, became the new British Resident.[115][121] Although the British Residents were officially instructed to keep out of the internal politics of Nepal, the Resident was courted by both the King as well as the Mukhtiyar. Hodgson was waiting for an opportunity to exploit the rift between the Mukhtiyar and the royal family and begin a more aggressive campaign to increase British influence and trading opportunities.[115][122] Hodgson also believed the large standing army to be a security threat[123] and that the border tensions could be pacified if the King was directly in control, rather than a Mukhtiyar who needed to keep on the right side of the army.[124] By 1834, Hodgson had come to a conclusion that he would not be able to have his way so long as Bhimsen was in control of the Nepalese administration;[125] thus he strongly sympathized with the Pande faction,[124] and he wished to install Fateh Jung Shah, who was more favorably disposed to him, as the Mukhtiyar.[126] Hodgson reported to Government of India on the dominance of Mukhtiyar Bhimsen to the position of King Rajendra Bikram Shah:

the Rajah is surrounded by the Minister's creature and is at present helpless. Bhim Sen has all the powers in his hands...The Rajah is so uncomfortable in his honorary confinement that the probability is the Minister may work on him with success to make voluntary retirement of his throne in favour of his infant son and in the highest conformity with the sacred code of the Hindu, to which His Highness is proved.[127]

In August 1834, Hodgson proposed to conduct a new commercial treaty between Nepal and Britain, which Bhimsen in principle agreed to but disagreed with several of the clauses.[126][128][129] At a time when his authority was diminishing, Bhimsen could not afford to antagonize the Resident; but at the same time, he could not accept his proposals and be seen as subservient to the British by the Nepalese court. Nevertheless, he tried to maintain a friendly and conciliatory attitude toward the Resident, in order to win him as his ally, by loosening the restrictions on his movements and granting direct access to the King.[130]

In the meantime, a royal letter was received from the Maharaja Ranjit Singh, ruler of Sikh Empire in Punjab, addressed to King Rajendra. The Nepalese court seized this opportunity to establish diplomatic contact with Punjab as well as other states such as Burma and Gwalior.[119] In April 1835, Bhimsen also hatched a plan to make a state visit to Britain, hoping to force Britain to acknowledge the sovereignty of Nepal; but since he could not make the visit himself, his nephew Colonel Mathabar Singh Thapa was chosen as the representative of Nepal, bearing a few gifts and a letter from King Rajendra addressed to King William IV.[128][130][131] The idea was initially received favorably by Hodgson as well as the Governor-General, who hoped that the mission could increase the trust between the two nations.[130] In this process, Mathabar Singh was promoted to Chota General; his brother, Ranbir Singh, the governor of Palpa, was made Full General; and Mathabar's nephew, the sixteen-year-old Sherjung Thapa, was made Commanding Colonel. Thus, Bhimsen managed to consolidate his military powers.[131] Both Rajendra and Samrajya Laxmi were also pleased with this plan, and on 1 November 1835, Bhimsen was conferred the title of Commander-in-Chief.[126][128] On 27 November 1835, Mathabar Singh left Kathmandu with a retinue of two thousand men, including 200 officers and 600 soldiers, for London via Calcutta.[126][132]

Mathabar was given a grand welcome in Calcutta by the acting Governor-General Charles Metcalfe; and while there, Mathabar started to indulge in needless luxuries and show offs.[133] Meanwhile, Hodgson sent a secret letter to Metcalfe asking him not to allow Mathabar to make a state visit to Britain.[134] Hence, Metcalfe was only willing to grant him the visa of an ordinary traveler, and not the diplomatic visa of a state representative. Mathabar thus returned to Nepal in March 1836, having wasted a vast sum of money, without accomplishing any of his goals.[128][134] The deliberate sabotage of Mathabar's mission was Hodgson's diplomatic attack against Bhimsen.[132][134] Until that time, it was widely believed by both the royal family as well as the common people that Bhimsen's good relationship with the high ranking British officials, since he was the only one allowed to communicate with them, was responsible for preventing the East India Company to take full control of Nepal. The mission's failure unambiguously revealed to everyone that this was not the case, and severely undermined Bhimsen's political credibility.[134] Mathabar Singh spent a sum of one lakh and fifty thousand in Calcutta on the fruitless mission.[135] Mathabar's extravagant expenditure was also heavily criticized by Samrajya Laxmi, since at that time the state coffer was in dire condition; and to pacify her, Bhimsen had to reimburse the extra expenses from his own pockets.[136]

Rise of the Pandes

By this time, Ranjang Pande, the youngest son of Damodar Pande, was stationed as a captain in the army in Kathmandu. He was aware of the disunity between Samrajya Laxmi and Bhimsen; and thus he had secretly expressed his loyalty to Samrajya Laxmi and had vowed to help her in bringing Bhimsen down for all the wrongs he had committed against his family.[137] Factions in the Nepalese court had also started to develop around the rivalry between the two queens, with the Senior Queen supporting the Pandes, while the Junior Queen supporting the Thapas.[138] About a month after Mathabar's return to Kathmandu, a child was born out of an adulterous relationship between him and his widowed sister-in-law. This news was spread all over the country by the Pandes, and the resulting public disgrace forced Mathabar to leave Kathmandu and reside in his ancestral home in Pipal Thok, Borlang, Gorkha.[137] To save face, Bhimsen gave Mathabar the governorship of Gorkha.[137]

Taking an advantage of Mathabar's absence in Kathmandu, the military battalions under his command were distributed to other courtiers during the annual muster at the beginning of 1837.[136] Nevertheless, Bhimsen managed to secure his and his family members' positions in the civil and military offices. An investigation was also started to check Bhimsen's expenditures in establishing various battalions.[136] Such events led the courtiers to feel that Bhimsen's mukhtiyari would not last very long; thus Ranbir Singh Thapa, in the hopes of becoming the next mukhtiyar, wrote a letter to the King asking him to be recalled to Kathmandu from Palpa. His wish was granted; and Bhimsen, pleased to see his brother after many years, made Ranbir Singh the acting Mukhtiyar and decided to go to his ancestral home in Borlang Gorkha for the sake of pilgrimage.[139] But in truth, Bhimsen had gone to Gorkha to placate his nephew and bring him back to Kathmandu.[139]

In Bhimsen's absence, Rajendra Bikram Shah established a new battalion, Hanuman Dal, to be kept under his personal command. By February 1837, both Rana Jang Pande and his brother, Ranadal Pande, had been promoted to the position of a kaji; and Ranajang was made a personal secretary to the King, while Ranadal Pande was made the governor of Palpa.[140] Ranjang was also made the chief palace guard, the position formerly occupied by Ranbir Singh and then Bhimsen. Thus, this curtailed Bhimsen's access to the royal family.[140] On 14 June 1837, the King took over the command of all the battalions put in charge of various courtiers, and himself became the Commander-in-Chief.[141][142]

Poisoning case

On 24 July 1837, Rajendra's youngest son, Devendra Bikram Shah, an infant of six months, died suddenly.[140][142] It was at once rumored that the child had died of poison intended for his mother the Senior Queen Samrajya Laxmi Devi: given at the instigation of Bhimsen, or someone of his party.[142][143][144] On this charge, Bhimsen, his brother Ranbir Singh, his nephew Mathbar Singh, their families, the court physicians, Ekdev and Eksurya Upadhyay, and his deputy Bhajuman Baidya, with a few more of the nearest relatives of the Thapas were incarcerated, proclaimed outcasts, and their properties confiscated.[142][143][145][146] The physicians Ekdev and Eksurya, being Brahmins, were severely tortured but spared, while Bhajuman Baidya was impaled and killed.[147][148] Under torture, Ekdev confessed, and thus confirmed a widely circulated rumor, that he was directed by Bhimsen to poison not just Devendra, but King Girvan as well.[149]

There is a general consensus among historians that Bhimsen was not behind the poisoning. Bhimsen had nothing to gain by killing an infant less a year old, and the accusation was simply a ruse to answer foreign inquiries on Bhimsen's imprisonment.[149] It was a general practice among the physicians of the time to check the strength of their medicine by first letting the mother taste it, before giving it to their new born.[138] It was later rumored that it was the Junior Queen who had actually contrived to kill the Senior Queen by poisoning the medicine intended for her new born. While the poison did not express itself on the intended Queen, it managed to kill the infant prince, and the powerless Bhimsen was made a convenient scapegoat.[146][150][151] Historian Gyanmani Nepal contends this to be closer to the truth.[150]

Dismissal from office and subsequent pardon

Immediately after the incarceration of the Thapas, a new government with joint Mukhtiyars was formed with Ranganath Paudel as the head of civil administration, and Dalbhanjan Pande and Rana Jang Pande as joint heads of military administration.[147] This appointment established the Pandes as the dominant faction in the court, and they started to make preparations for war with the British in order to win back the lost territories of Kumaon and Garhwal.[152] While such war posturing was nothing new, the din the Pandes created alarmed not just the Resident Hodgson[152] but the opposing court factions as well, who saw their aggressive policy as detrimental to the survival of the country.[153] After about three months in power, under pressure from the opposing factions, the King removed Ranjang as Mukhtiyar and Ranganath Paudel, who was favorably inclined towards the Thapas, was chosen as the sole Mukhtiyar.[148][154][155][153]

Fearful that the Pandes would re-establish their power, Fatte Jang Shah, Ranganath Poudel, and the Junior Queen Rajya Laxmi Devi obtained from the King the liberation of Bhimsen, Mathabar, and the rest of the party, about eight months after they were incarcerated for the poisoning case.[154][155][156] Some of their confiscated land, as well as the Bagh Durbar, was also returned. Upon his release, the soldiers loyal to Bhimsen crowded behind him in jubilation and followed him up to his house; a similar treatment was given to Mathabar Singh and Sherjung Thapa.[153] Although pardon had been granted to Bhimsen, his former office was not re-instated; thus he went to live in retirement at his patrimony in Borlang, Gorkha.[155][156]

However, Rangnath Poudel, finding himself unsupported by the King, resigned from the Mukhtiyari, which was then conferred on Pushkar Shah; but Puskhar Shah was only a nominal head, and the actual authority was bestowed on Ranjang Pande.[157] Sensing that a catastrophe was going to befall the Thapas, Mathabar Singh fled to India while pretending to go on a hunting trip; Ranbir Singh gave up all his property and became a sanyasi, titling himself Abhayanand Puri; but Bhimsen Thapa preferred to remain in his old home in Gorkha.[156][158] The Pandes were now in full possession of power; they had gained over the King to their side by flattery. The Senior Queen had been a firm supporter of their party, and they endeavored to secure popularity in the army by promises of war and plunder.[157]

Suicide: 1839

At the beginning of 1839, Ranjang Pande was made the sole Mukhtiyar. However, knowledge about Ranjang's war preparations and his communication with other princely states of India, fomenting anti-British sentiments, alarmed the Governor-General of the time, Lord Auckland, who mobilized some British troops near the border of Nepal.[158][159] In order to resolve this diplomatic fiasco, Bhimsen was recalled from Gorkha and the rest of his confiscated property was also released.[160][161] Bhimsen suggested some of the battalions under Ranjang's command to be given to other courtiers, thus severely weakening Ranjang's military power, and in the process convincing the British that Nepal was not on the path to war.[81] The King agreed to this arrangement; however, this aroused a strong suspicion in Samrajya Laxmi, who determined to eradicate Bhimsen's influence permanently.[81]

In April 1839, the accusation of poisoning the young prince in 1837, along with two other fabricated cases, was revived against Bhimsen and his party, and forged papers and evidence were produced professing to incriminate him.[160][81][162] Bhimsen appealed for justice and tried to defend himself, but the King, blindly believing the forgeries, denounced him as a traitor and put him in house arrest in a room at the ground floor of his own Bagh Durbar.[160][162][163] Although pardon had already been given, based on these forged evidences, the court physicians, Ekdev and Eksurya Upadhyay were again arrested and tortured. Except for Mathabar Singh, who managed to escape to India, rest of the Thapa family were again arrested, their properties confiscated, were declared outcasts, and were proclaimed to be expelled from every public office for seven generations.[163][145][164]

While under house arrest, Bhimsen smuggled a letter to the Resident Hodgson appealing him to intervene on his behalf, which Hodgson refused at that moment but sought permission from his superiors to do so.[165] Meanwhile, Bhimsen's third wife, Bhakta Kumari, happened to insult the Senior Queen Samrajya Laxmi, who upon hearing about this insult, was so angered that she order Bhakta Kumari to be removed from Bagh Durbar and put in a common jail.[163] After this, a rumor started to spread around Kathmandu that Bhakta Kumari would be stripped off her clothes and paraded through the streets of the city.[164][163] This rumor also fell on Bhimsen's ears; and unable to bear such indignity, Bhimsen attempted suicide by slitting his throat with a khukuri on 28 July 1839.[163] The news of this attempted suicide further angered the King and the Queen, who came to look at his body, and instead of feeling sympathy for the old minister and ordering immediate medical care, Bhimsen's blood-soaked, unconscious body was ordered that same day to be dragged through the streets and dumped by the same bank of Bishnumati river, where Bhimsen had dumped the dead bodies of 45 people 33 years ago during the Bhandarkhal massacre.[166] Bhimsen finally died nine days later, surrounded by vultures, jackals, and dogs, on 5 August 1839, at the age of 64.[166] Since suicide was considered a grave crime, soldiers were stationed at his death spot so that his body would not be removed and given ordinary cremation rites; and his body was allowed to be devoured by scavenging animals.[160][164][166] On the spot where Bhimsen drew his last breath, a Shiva temple by the name Bhim-Mukteshwar was later constructed by his nephew Mathabar Singh Thapa.[167]

While there is a general consensus on the cause and circumstances of Bhimsen's death, there is a disagreement on the exact date of his death. Baburam Acharya contends that Bhimsen attempted suicide on 28 July in his house and died nine days later on 5 August by the banks of Bishnumati;[166] while Henry Oldfield, K.L. Pradhan, and Gyanmani Nepal contend that the suicide was attempted on 20 July and the death occurred nine days later on 28 July in his house, only after which his dead body was disposed by the banks of Bishnumati.[164][160][168]

Aftermath

.jpg)

The death of Bhimsen Thapa did not resolve the factional fighting at court. Five months after Bhimsen's death, Ranajang Pande was again made prime minister; but Ranajang's inability to control the general lawlessness in the country forced him to resign from prime minister's office, which was then conferred on Puskar Shah, based on Samrajya Laxmi's recommendation.[169] While Pushkar Shah was not as anti-British as Ranajang Pande, he was nevertheless unfavorably predisposed towards them. During his tenure, a border dispute with the British in April 1840 resulted in Governor-General of India, 1st Earl of Auckland dispatching some troop near the Nepalese border once again, which Pushkar managed to resolve diplomatically.[170] There was also a brief army mutiny in June 1840, as a reaction against the government's attempt to cut military salary, during which houses of several noblemen in favor of this unpopular act were vandalized and burned. The mutiny was calmed only after King Rajendra publicly agreed not to implement the reform.[171] Taking advantage of this mutiny, Resident Hodgson sent an incriminating report against the Nepalese government to his superiors in Calcutta. The Governor-General demanded the King to dissolve the incumbent government and appoint ministers more favorable towards the British. Thus, Pushkar Shah and his Pande associates were dismissed, and Fateh Jang Shah was appointed prime minister in November 1840.[172] Dismissal of Pushkar Shah curtailed Samrajya Laxmi's power. When Rajendra refused to abdicate in favor of their eldest son Surendra, the heir apparent, she left Kathmandu and settled at a border town in terai. However, during the monsoon season, Samrajya Laxmi was afflicted with malaria from which she died in October 1841 at the age of twenty-seven.[173]

The death of the Senior Queen Samrajya Laxmi allowed the emergence of the Junior Queen Rajya Laxmi and Crown Prince Surendra onto the political stage. To consolidate her political influence and see her own son, rather than the heir apparent, Surendra, succeed on the throne, Rajya Laxmi had obtained pardon for Sherjung Thapa and other jailed members of Thapa family. It was only after this that Bhimsen Thapa managed to get a symbolic funeral rite in August 1841.[174] Thus, the Nepalese court was split into three factions centered around the King, the Queen, and the Crown Prince. Fateh Jung and his administration supported the King, the Thapas supported the Junior Queen, while the Pandes supported the Crown Prince. The resurgent Thapa coalition succeeded in sowing animosity between Fateh Jung's ministry and the Pande coalition, who were swiftly imprisoned.[175] During his two years in power, Fateh Jung was able to maintain a rule of law in the country; however, after the incarceration of the Pandes, nobody could rein in the worsening sadistic tendencies, sometimes with fatal consequences, of Surendra, who was then still a minor.[note 16] Under immense pressure from the Queen and the nobility, along with the backing from army and the general populace, the King in January 1843 handed the highest authority of the state to his Junior Queen, Rajya Laxmi, curtailing both his own and his son's power.[177][178]

The Queen, seeking support of her own son's claims to the throne over those of Surendra, invited Mathabar Singh Thapa back after almost six years in exile.[179] Upon his arrival in Kathmandu, an investigation of his uncle's death took place, and a number of his Pande enemies were massacred.[180] As for Ranajang Pande, he had by that time contracted mental illness and would not have posed any threat to Mathabar. Nevertheless, Ranajang was paraded through the streets and made to witness the execution of his family members, after which he was forced to commit suicide by poison.[180] By December 1843, Mathabar Singh was appointed prime minister; but after a year in power, he alienated both the King and the Queen by supporting Surendra's claim over the throne. On May 17, 1845, he was assassinated, on both the King and Queen's orders, by his nephew, Jang Bahadur Kunwar. The death of Mathabar Singh ended the Thapa hegemony and set the stage for Kot massacre and the establishment of Rana Dynasty, a dictatorship of hereditary prime ministers, which was founded on the basic template provided by Bhimsen Thapa. These events provided the long period of stability the country needed but at the cost of political and economic development.[181]

Reforms and Heritages

Reforms

Bhimsen implemented the reorganization of Nepalese Army on the basis of European military system and the maintenance of the newly reorganized strong army was done from the confiscation of Birta funds of 1805.[182] He appointed French military officials to modernize the military on the basis of French military ranks and uniforms. Military jobs were made attractive by increasing facilities including Jhara (porter) facility even in the peacetime under his Mukhtiyarship.[182] Due to extensive lack of labour forces in the country, he issued legal obligations to all adult males of all castes to provide compulsory labour to the state subject to royal exemptions. Those state jobs included construction and maintenance of forts, bridges, roads, and production of ammunition for military expeditions.[183] Hulaki (postal) system from Kathmandu to the western front was implemented on 1804 through rotational relays of porters. In 1808 during the premiership of Bhimsen, it was reported that minors were engaged in Hulaki services in the villages with small Hulaki households. The regulation issued by Bhimsen's government was to increase the number of relays in the villages consisting low Hulaki households and person forcing minors and females for personal Hulaki services would be severely punished.[184] These Jhara (porter) services for Hulaki system were regularly required due to which some were compensated with land under Adhiya (half-ownership) tenure and others in the form of cash wages compensation.[185] Regulations issued on July 1809 was:

In the areas west of Dharmasthali (in Kathmandu) and east of Bheri River, inspect whether or not Hulaki outposts for transport or mail have been established as mentioned in the previous order. According to this order, Hulaki porters had been granted a 50 per cent concession in the Walak levies, in addition to full exemption from (other) compulsory labour obligations and taxes on their homesteads...

In areas west of Bheri river and east of Jamuna river, make an estimate of the amount required for payment to Hulaki porters employed for the transport of mail on the basis of sum sanctioned in the previous order and the sum required according to arrangements made this year for different areas and submit a report accordingly.[185]

In 1807 dealing with slavery, the government of Bhimsen directed revenue officials to collect outstanding taxes and fines in terms of cash and ordered the freedom of all enslaved farmers in case of defaulting taxes and no farmer would be enslaved for non-payment of taxes. In 1812, he imposed a general restriction on human trafficking in Garhwal Sirmur and other areas.[186] Around 1808, Bhimsen ordered the reclamation of wastelands in Terai region for increasing state revenue and offered irrigation facilities to settlers reclaiming the wastelands.[187] In places where there was a lack of tenants, farmers were allocated the wastelands with tax exemption and loan was provided for new incoming settlers. The wastelands reclamation policy was largely advantageous to the government and tenants, and was greatly successful in Eastern Terai.[187] For the coordination of this policy, officials were appointed all over the state in 1811.[188] The trade policy of Bhimsen Thapa was influenced from King Prithvi Narayan Shah who believed foreign (in the context English) traders would weaken the economy of the country and impoverish the general people. Customs offices were relocated within the country to reduce discomfort to native traders. Essential arrangements and facilities were provided to native traders and officials were warned not to intimidate native traders.[188] Bhimsen is quoted to have said:

If Tibetans and Firangis [i.e. foreigners or, in the contemporary context, Englishmen] meet and trade with each other, our ryots and traders will lose their employment and result will not be good.[189]

After 1807, markets were opened in the Terai and Inner Terai under direct governmental efforts and supervision to facilitate native traders. For instances; in 1809, market towns were made at Hitaruwa in Makawanpur and at Bhadaruwa in Saptari.[189] Indian traders were also encouraged to trade within the country[188] and Nepalese officials were instructed to take care of the development of border markets, land reclamation and settlement, and protection of land encroachment.[189] In 1811, timber exports from Chitwan to Calcutta were introduced together with the diversification of agricultural products to strengthen the export. Also, mining and minting coins were undertaken by the Bhimsen government.[189] Bhimsen considered Churia hills as the basic line of defense of the Kingdom of Nepal. He thus wanted to build communications to the western parts such as Kumaon, Garhwal and Yamuna-Sutlej region of Kingdom of Nepal and block the strategic routes to the Kathmandu valley.[190] The possessions of passers-by were strictly searched and even private letters were censored. Such was implemented to prevent outflow of secret information of Nepal to British Company government.[191] Passport system was introduced to check the access to the capital city with officials appointed on the Churai routes with instructions as follows:

In case you permit any person, irrespective of his status, leaving this side to proceed onward even though he does not have (a document bearing) signature of passports authority. We shall behead you.[192]

Bhimsen put forth the principle of Equality before the law in Nepal. In 1826, a regulation was issued by him through Lalmohar (Red Seal) of Maharaja directing Kaji Dalbhanjan Pande to maintain the sanctity of judiciary and it further stated:

irrespective of castes, creeds or position in the society, all are same in the eyes of law.[191]

Mohi (tenant farmers) felt it easier to pay taxes in kind to their Zamindars due to cash shortage. He directed the Zamindars to accept foodgrain as tax and not to harass the farmers. The regulation further directed that it was the responsibility of Zamindars to make arrangements for cash and not of the farmers.[193] The anti-bribery regulations was issued due to reports of Zamindars, Amalis and regional officials taking up bribery from people in the far-flung provinces. Bhimsen through his regulations declared it illegal to give or take any form of bribes or gifts from people.[193] Merchants at Ridi in 1829 and Tansen in 1830 lost their thatched shopping houses to fire. The affected merchants demanded individual rights on property and allowance of building concrete shopping houses. He accepted the merchants' proposal of building concrete shopping houses and allowed individual rights on property.[193] Due to long ongoing unification campaigns of Nepal, there was anarchy in Nepalese administration before Bhimsen's Mukhtiyarship. In Achham Province, Zamindars, Amalis and traders perpetrated great injustice to farmers by increasing heavy interest on loans, to which farmers revolted. Bhimsen being moved by the plight of the victims issued Lalmohar with binding instructions to write off outstanding dues at once.[194]

The socio-religious customs like birth and death ceremonies among Newar community was leading to indebtedness. The priests took up huge ceremonial fees and failure to adhere such customs led people to excommunication in the Newar society. In 1830–31, Bhimsen by issuing Lalmohar, a regulation was introduced with limit of ceremonial fees and the amount of expenditures was restricted.[195] The children of debtors were acquired by the traders against the accumulated interest of the loans and were sold on profit. The feudal lords did not allowed them legal facilities and considered slaves as non-human. Bhimsen challenged the widespread notion of inhuman treatment of slaves.[196] In 1830, Bhimsen having introduced anti-slavery regulations beforehand in 1807[186], restricted all of the Danuwar traders in Western Nepal to acquire and sell Kariya slaves and also freed slaves from the custody of their owner.[197] The regulation was targeted to provide legal rights to slaves and boost their morale. Six years afterwards, he restricted ban on sales of children prevalent among Magar community of Marsyangdi and Western Pyuthan.[196] The slave trading was made illegal on various parts of Nepal by Bhimsen. It was considered one of the greatest achievement in the history on comparison to their British counterparts. Wilberforce in England was obtaining the public mandate against it while one of the most powerful Prime Minister in the world (in 1800s) – William Pitt was hesitant to outlaw the slave trading.[196]

Heritages built

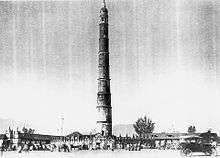

In 1811, he he built the bridge at Thapathali over Bagmati River connecting strategically significant cities; Kathmandu and Patan.[198] In 1825, he built the famous Dharahara Tower on the orders of then reigning Queen Tripurasundari of Nepal. Beforehand, he had already built the taller antecedent of Dharahara for himself on 1824. The taller Dharahara collapsed on 1833 Nepal earthquake and was never repaired. The smaller Dharahara had 11 storeys before 1934 Nepal earthquake reduced it to two storeys.[199][200][201] The original Dharahara Tower built by Bhimsen was 225 feet tall[202] and was completely destroyed in the 2015 Nepal earthquake.[203] It was recognized by UNESCO.[204] Dharahara is considered as majestic and nationalistic legacy of Bhimsen.[205] The feat of completing twin Dharahara towers by Bhimsen in a span of two years was considered a unique architectural achievement.[199]

In 1811, he also constructed Bagh Durbar after being appointed General[198] reside near to Basantapur Palace. He initially moved from Gorkha district to Thapathali Durbar and further to Bagh Durbar.[206] It had a spacious Janarala Bag (General's Garden), pond and many temples glorifying the Mukhtiyar General. Later when Thapa rule was revived again, PM Mathabarsingh Thapa recaptured the lost palace and began to reside for two more years.[207] The National Museum of Nepal at Chhauni was once a residence of Bhimsen. The building has collection of bronze sculptures, paubha paintings and weapons including the sword gifted by King of France Napoleon Bonaparte.[208]

Legacy and memorials

Bhimsen Thapa was a military leader and a de facto ruler of Nepal.[209] Bhimsen is regarded as one of the national heroes of Nepal.[210] He was considered a clever, farsighted, politically aware and practically diplomatic politician.[8] He was considered by many as a patriotic nationalist. His contemporary King Rana Bahadur Shah of Nepal had told that

If I die the nation will not die, but if Bhimsen dies the nation will collapse.[210]

Similarly, British writer and journalist Perceval Landon had told

Nepal is Bhimsen and Bhimsen is Nepal.[210]

Historian Kumar Pradhan asserts that Bhimsen could not be termed as military dictator because he was dependent on Pajani System (annual renewal) for renewal of his every tenure of office.[191] Pradhan also asserts that Bhimsen did not manipulate the Army which could be seen when he was not backed up by any soldiers after his removal from Mukhtiyarship.[198] Pradhan asserts that administrative system of Nepal was people centric and upward mobility. Most of the Thapa Bharadars (courtiers) were appointed before 1816 and there was no monopoly of single family in the inner circle of court.[211] Perceval Landon had also expressed the bitterness of Bhimsen's death in the quote:

His was a life of contrast and no Greek tragedy has ever presented a more dramatic catastrophe than his fearful end.[212]

German philosopher and historian Karl Marx quoted that

Bhimsen was the only man in Asia who braved to protest submission to colonists.[210]

An English writer remarked about him as;

He was the first Nepalese statesman who grasped the meaning of the system of protectorate which Lord Wellesley had carried out in India. He saw one native state after another came within the net of British Subsidiary Alliance and his policy was steadily directed to save Nepal from similar fate.[213]

Nayaraj Panta considers that Bhimsen's action to suppress British influences on Nepal and strengthening of Nepalese military forces was important to save the fate of the only Hindu Kingdom in the world.[214]

Nepalese-Canadian essayist Manjushree Thapa had written a column about him. She wrote:

He did not succeed in the 1814–16 war with the British, but the Thapas love him nonetheless because he tried so hard to control those pesky imperialists, overseeing military battles and negotiating treaties himself while trying to beat down Hodgson.[215]

There is a park dedicated to him constructed in the Gorkha Municipality called Bhimsen Park. It is in two kilometers walk from Gorkha Darbar. The park constitutes 3 ropani of land and was used by descendants of Thapa dynasty for ritual purposes in the Dashain festival.[216]

Family

Bhimsen Thapa had three wives as per the stone inscription of Bhimbishwar Mahadev temple at Bungkot. His only son died at a young age in 1796 and his three daughters – Lalita Devi, Janak Kumari and Dirgha Kumari were married to Pande nobles Uday Bahadur, Shamsher Bahadur and Dal Bahadur respectively.[8] Uday Bahadur and Colonel Shamsher Bahadur were the sons of Kaji Bir Keshar Pande[217] and Sardar Dal Bahadur was the son of Bir Keshar's cousin Garud Dhoj Pande, all belonging to Tularam Pande family.[218]

| Bir Bhadra Thapa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Satyarupa Maya | Amar Singh Thapa | ? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bhimsen Thapa | Nain Singh Thapa | Bhaktawar Singh Thapa | Amrit Singh Thapa | Ranbir Singh Thapa | Ranbam Thapa | Ranzawar Thapa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ? (son) | Lalita Devi Pande | Janak Kumari Pande | Dirgha Kumari Pande | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

Clothes worn by Mukhtiyar Bhimsen Thapa

Clothes worn by Mukhtiyar Bhimsen Thapa Clothes worn by Mukhtiyar Bhimsen Thapa

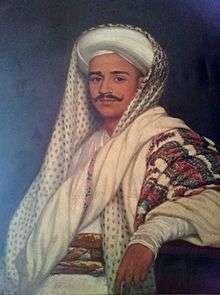

Clothes worn by Mukhtiyar Bhimsen Thapa Portrait of Bhimsen's godson and nephew later Prime Minister Mathabar Singh Thapa in style of his uncle Bhimsen

Portrait of Bhimsen's godson and nephew later Prime Minister Mathabar Singh Thapa in style of his uncle Bhimsen Statue of Queen Tripurasundari, Bhimsen's niece and biggest supporter

Statue of Queen Tripurasundari, Bhimsen's niece and biggest supporter Thapathali Durbar complex, residence of Bhimsen Thapa between (1798-1804) when he was a Hajuriya (advisor and secretary to king)

Thapathali Durbar complex, residence of Bhimsen Thapa between (1798-1804) when he was a Hajuriya (advisor and secretary to king) Portrait of Ranabir Singh Thapa, Bhimsen's youngest brother and a significant Bharadar in the Royal court

Portrait of Ranabir Singh Thapa, Bhimsen's youngest brother and a significant Bharadar in the Royal court Portrait of Ujir Singh Thapa, Bhimsen's warrior nephew

Portrait of Ujir Singh Thapa, Bhimsen's warrior nephew Letter received by Mukhtiyar (PM) Bhimsen Thapa and 2nd Kazi (Deputy PM) Ranadhoj Thapa sent by Bada Kaji Amar Singh Thapa's letter signed by his private black seal

Letter received by Mukhtiyar (PM) Bhimsen Thapa and 2nd Kazi (Deputy PM) Ranadhoj Thapa sent by Bada Kaji Amar Singh Thapa's letter signed by his private black seal Letter received by Mukhtiyar (PM) Bhimsen Thapa and 2nd Kazi (Deputy PM) Ranadhoj Thapa sent by Kaji Ranabir Singh Thapa's letter signed by his private black seal

Letter received by Mukhtiyar (PM) Bhimsen Thapa and 2nd Kazi (Deputy PM) Ranadhoj Thapa sent by Kaji Ranabir Singh Thapa's letter signed by his private black seal Letter received by PM Bhimsen Thapa and Kazi Ranadhoj Thapa sent by (Pvt. seal L to R) Bakhat Singh Sardar, Dalbhanjan Pande (Pande Kazi), Ranabir Singh Thapa, Kaji Narsingh Thapa (Elder Amar Singh Thapa's another son) and sundry captains

Letter received by PM Bhimsen Thapa and Kazi Ranadhoj Thapa sent by (Pvt. seal L to R) Bakhat Singh Sardar, Dalbhanjan Pande (Pande Kazi), Ranabir Singh Thapa, Kaji Narsingh Thapa (Elder Amar Singh Thapa's another son) and sundry captains Letter sent to PM Bhimsen Thapa and Kazi Ranadhoj Thapa by then Colonel Mathabar Singh Thapa

Letter sent to PM Bhimsen Thapa and Kazi Ranadhoj Thapa by then Colonel Mathabar Singh Thapa

References

Footnotes

- ↑ The position of Mukhtiyar was roughly equivalent to a prime minister. The first Mukhtiyar to title himself as a prime minister, as per the British convention, was Bhimsen's nephew, Mathabar Singh Thapa.[3]

- ↑ Not to be confused with the better-known commander of Gorkhali forces in the Gurkha War with the same name. The two Amar Singh Thapas are differentiated by the qualifier Bada (greater) and Sanu (lesser).

- ↑ Rana Bahadur Shah had two legitimate wives before marrying Kantavati. His first wife was Rajrajeshwori Devi with whom he begot one daughter. His second wife was Subarnaprabha Devi with whom he begot two sons, Ranodyot Shah and Shamsher Shah. Ranodyot Shah was the eldest male heir apparent of Rana Bahadur Shah.[14]

- ↑ From here on Rana Bahadur Shah became known as Swami Maharaj. Rana Bahadur however was an ascetic in name only. Although Rana Bahadur left the royal duties after his abdication, he did not relinquish any of its privileges and luxuries.[18]

- ↑ The exact reason for Rajrajeshowri's departure from Varanasi is a matter of controversy. In Varanasi, Rana Bahadur had sold all her jewelry to support his dissipation and had acquired many new wives and concubines. He regularly mistreated Rajrajeshowri and once even humiliated her in public before a prostitute. So, her sense of frustration could have made her leave Varanasi. But at the same time, there is also evidence to support that Rana Bahadur sent her back to Kathmandu with a political motive.[30]

- ↑ The treaty was signed by Gajraj Misra, on the behalf of Nepal Durbar, and Charles Crawford, on the behalf of East India Company, in Danapur, India. Among the articles in the treaty, it decided on perpetual peace and friendship between the two states, on the pension for Rana Bahadur Shah, the establishment of a British Residency in Kathmandu, and an establishment of trade relations between the two states.[34][26]

- ↑ Knox had previously accompanied Captain William Kirkpatrick in the 1792 British diplomatic mission to Nepal as a lieutenant in charge of the military escort. In Knox's 1801 mission, he was accompanied by experts like the naturalist Francis Buchanan-Hamilton, who later published An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal in 1819, and the surveyor Charles Crawford, who made the first scientific maps of Kathmandu valley and of Nepal, and proposed that the Himalayas might be among the highest mountains in the world.[35][36][37][38]

- ↑ Rana Bahadur had borrowed a lot of money from many different people: Rs 60,000 from Dwarika Das; Rs 100,000 from Raja Shivalal Dube; Rs 1,400 from Ambasankar Bhattnagar. Similarly, he had borrowed a lot of money from the East India Company as well. However, Rana Bahadur was reckless in the manner he spent the borrowed money. For instance, he had once given an alms of Rs 500 to a Brahmin.[40] For more details see [41]

- ↑ Among those who managed to escape to India were Damodar Pande's sons Karbir Pande and Ranjang Pande.[51]

- 1 2 According to Regmi: Birta meant an assignment of income from the land by the state in favor of individuals, who by virtue of their occupation cannot participate in economic pursuits (such as priests, religious teachers, soldiers, and members of nobility and the royal family) in order to provide them with a livelihood. Birta rights did not include protection from resumption or confiscation by the state. Land granted to guthi system was exempt from such arbitrary government actions. In a guthi system, land was endowed by the state or birta owners for the establishment or maintenance of such religious or charitable institutions such as temples, monasteries, schools, hospitals, orphanages, and poorhouses. Jagir was an assignment of income from state-owned lands (all the land in the state's domain, also known as raikar) as emoluments of office to government employees and functionaries. Jagir lands assignments were made only for current services, while land granted in appreciation of past services were associated with the birta system. The rights of birta and guthi owners and jagir holders were granted by a royal order which made them lords and masters of the land and the peasant in every sense.[57]