Mathabarsingh Thapa

| Mukhtiyar General Mathabar Singh Thapa Bahadur | |

|---|---|

|

मुख्तियार जनरल माथवरसिंह थापा बहादुर | |

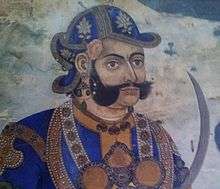

First Nepalese Head of Government with title Prime Minister and crown, Mathavar Singh Thapa | |

| 7th Mukhtiyar and First Prime Minister of Nepal | |

|

In office 1843 A.D. – 1845 A.D. | |

| Preceded by | Fateh Jung Shah |

| Succeeded by | Fateh Jung Shah |

| Commander-in-Chief of Nepal Army | |

|

In office 1843 A.D. – 1845 A.D. | |

| Preceded by | Rana Jang Pande |

| Succeeded by |

shared by: Gagan Singh Bhandari Jang Bahadur Kunwar Fateh Jung Shah Abhiman Singh Rana Magar |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1798 A.D. Borlang, Gorkha |

| Died |

17 May 1845 A.D. (aged 47) Hanuman Dhoka Palace, Kathmandu |

| Children |

Ranojjwal Singh Thapa[1] Col. Bikram Singh Thapa Col. Amar Singh Thapa[2] |

| Mother | Rana Kumari Pande |

| Father | Nain Singh Thapa |

| Relatives |

Bhimsen Thapa (uncle) Queen Tripurasundari (sister) Balbhadra Kunwar (cousin) Jung Bahadur Rana (nephew) |

| Residence |

Thapathali Durbar Bagh Durbar |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | Kala Bahadur |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | Nepal Army |

| Rank |

Colonel (1831-1837) General & Commander-in-Chief (1843-1845) |

| Battles/wars | Anglo-Nepalese War as soldier |

Mathabar Singh Thapa or Mathawar Singh Thapa ![]()

Early years

Not much is known of Mathabar Singh Thapa's childhood. He was born in Borlang, Gorkha. He was the son of Kaji Nayan Singh Thapa who was killed in the war against the Kingdom of Kumaon. He was a nephew of Bhimsen Thapa and also the maternal uncle of Jang Bahadur Rana.[5] Through his mother's side, he was the grandson of Kaji Ranajit Pande, who was the son of Kaji Tularam Pande.[5] Kaji Tularam Pande was a cousin of Kaji Kalu Pande.

Rise to Power

Mathabar Singh Thapa had exiled to India when Bhimsen Thapa was maliciously accused to be guilty of murdering the King Rajendra's son who was 6 months old. After assigning administrative authority to Junior Queen Rajya Laxmi Devi by King Rajendra Bikram Shah on January 1843, she immediately asked Mathabar Singh to return to Nepal, to which Mathabar Singh left Shimla to stop at Gorakhpur for detailed study of political situation of Nepal.[6] Mathabar Singh's nephew Kaji Jung Bahadur Kunwar was send to persuade his uncle afterwhich he arrived in Kathmandu Valley in April 1843.[6] Historian Balchandra Sharma writes that Mathabar Singh arrived on 17th April 1843 where a great welcome was organized for him.[7] After consolidating his position, he successfully led to the murder of all his political adversaries Karbir Pande, Kularaj Pande, Ranadal Pande, Indrabir Thapa, Ranabam Thapa, Kanak Singh Mahat, Gurulal Adhikari and many others, in several pretexts. Mathabar Singh became Mukhtiyar as well as Minister and Commander-In-Chief of the Nepalese army in November 1843 [6] by the second queen of Rajendra, Queen Rajya Laxmi with the hope of making her own son, Prince Ranendra as the king of Nepal.[8] Though he was declared Mukhtiyar and as well as Minister and Commander-In-Chief on November 1843, his appointment letter was issued only on Aswin Badi 7, 190l (i.e. September 1844):

From King Rajendra, To Mathbar Singh Thapa Bahadur, son of Nain Singh Thapa, grandson of Ambar Singh Thapa, resident of Gorkha. We hereby appoint you as Mukhtiyar of all civil and administrative affairs throughout our country, as well as Prime Minister, Commander-In-Chief and General with Jagir emoluments amounting to Rs 12,401. Remain in attendance during war and other occasions as commanded by us, be faithful to our salt and utilize the following lands and revenues as your Jagir with due loyalty. (Particulars of lands and revenues follow).

— Appointment of Mathbar Singh Thapa as Prime Minister by Mahesh Chandra Regmi[9]

Consolidation of Power

Before he was made the Minister and the Commander-In-Chief, he had led to the murder of almost all of his enemies and political adversaries. Having seen the fall of Bhimsen Thapa, he believed that having a personal army would prevent his own downfall; so he raised three regiments dedicated to him and only him. He built army barracks around his house for his personal protection. For this, he used the army like slaves, for which the resident Sir Henry Lawrence advised him not to do so.[10] However, too over-confident in his power, MathabarSingh Thapa ignored him. He even claimed that since the time of Prithvi Narayan Shah, he would be the first Prime Minister to die of old age and not out of conspiracy. In 1845 January 4, he declared himself as the "Prime Minister of Nepal". This was the first time anyone had been titled "Prime Minister" in the history of Nepal. All before him were either titled as Mukhtiyar or Mul Kajis. It is believed that at that time he had become even more powerful than the King of Nepal. His power and over-influence in the Nepalese politics and even in the personal life of the monarchy itself led to the eclipse of his power and his downfall by the hands of Jang Bahadur Rana.

Downfall

When Mathabar Singh Thapa declined the Queen's request to help her make her own son king, the Queen joined those against him and plotted his downfall. But just to appease him, he was provided the title of "Prime Minister" while conspiracy to murder him was going on behind. Finally, when all the preparations for his murder were made, he was called to the Royal Palace at night, informing him incorrectly, that the Queen had been ill from some disease. Though he was warned by his own son, and his mother, he went to the palace. When he was sleeping Jang Bahadur was hiding under his bed. He was shot multiple times on his back from under the bed by Jang Bahadur Rana where he immediately died. The next day King Rajendra declared that he had himself killed Mathabar Singh Thapa accusing him of several activities that he had done to undermine his own (Rajendra's) power.[11]

Aftermath

The murder of Mathabar Singh Thapa led to the political instability in Nepal. Though, Fatte Jungh Shah was declared the Prime Minister (1845 September 23), Gagan Singh had more regiments (7) of the army under him and was more powerful. Jung Bahadur Rana also had 3 regiments under him. Fatte Jungh Shah himself had 3 regiments of the army under his control. Also Gagan Singh had the special support of the queen Rajya Laxmi Devi. British Resident Sir Henry Lawrence once mentioned that, "If there is struggle for power, that struggle will be between Gagan Singh and Jung Bahadur."[12] Ultimately, the extreme power of Gagan Singh led to his assassination by King Rajendra and Prime minister Fatte Jungh Shah in 1846 September 14 at 10 P.M.. The assassination of Gagan Singh led to the Kot massacre and ultimately, the rise of Jung Bahadur Rana.

Legacy

Mathabarsingh Thapa was the first prime minister of Nepal to wear a crown. The 104 year-ruling Rana Dynasty was also related to him.

Gallery

Portrait of Colonel Mathabar Singh Thapa (1831)

Portrait of Colonel Mathabar Singh Thapa (1831) Thapa Kaji Mathabar Singh's painting from the Prime Minister's office

Thapa Kaji Mathabar Singh's painting from the Prime Minister's office Mathabar Singh wearing the crown

Mathabar Singh wearing the crown Mathabar Singh Thapa in a royal attire

Mathabar Singh Thapa in a royal attire Mathabar Singh Thapa

Mathabar Singh Thapa Mathabar Singh's letter signed by his cover seal, to PM Bhimsen Thapa 1884 B.S.

Mathabar Singh's letter signed by his cover seal, to PM Bhimsen Thapa 1884 B.S.

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Mukhtiyar is translated as Chief Authority and was roughly equivalent to a Prime Minister or Head of Government.

- ↑ His coronation of Premiership was the first in Nepal thereby making him the First Prime Minister and Commander-in-chief of Nepal as many of his predecessors bore the same position but not the title.

Notes

- ↑ Shrestha, Shree Krishna (1996) "Jangabahadura; Kathmandu

- ↑ Shaha, R. (1990). 1769-1885. Manohar. ISBN 9788185425030. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ↑ Kandel 2011, p. 10.

- ↑ Acharya, Baburam (2057 B.S.) (2000). Aba Yesto Kailei Nahos. Sajha Prakashan.

- 1 2 JBR, PurushottamShamsher (1990). Shree Teen Haruko Tathya Britanta (in Nepali). Bhotahity, Kathmandu: Vidarthi Pustak Bhandar. ISBN 99933-39-91-1.

- 1 2 3 Regmi 1971, p. 17.

- ↑ Sharma, Balchandra (2033 B.S.). Nepal ko Aitehasik Rooprekha. Varanasi: Krishna Kumari Devi. p. 295. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - ↑ Regmi 1971, p. 18.

- ↑ Regmi 1971, p. 24.

- ↑ Indo-Nepalese Relations : 1816 to 1877. Delhi: S. Chand and Co. 1968. p. 228.

- ↑ Acharya, Baburam (2057 B.S.). Aba Esto Kailei Nahos. Kathmandu: Sajha Prakashan. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - ↑ Edwards, Herbert (1873). Life of Sir Henry Lawrence, Part II. London: Smith Elder and Co. p. 470.

Sources

- Acharya, Baburam (Nov 1, 1974) [1957], "The Downfall of Bhimsen Thapa", Regmi Research Series, Kathmandu, 6 (11): 214–219, retrieved Dec 31, 2012

- Acharya, Baburam (2012), Acharya, Shri Krishna, ed., Janaral Bhimsen Thapa : Yinko Utthan Tatha Pattan (in Nepali), Kathmandu: Education Book House, p. 228, ISBN 9789937241748

- Joshi, Bhuwan Lal; Rose, Leo E. (1966), Democratic Innovations in Nepal: A Case Study of Political Acculturation, University of California Press, p. 551

- Kandel, Devi Prasad (2011), Pre-Rana Administrative System, Chitwan: Siddhababa Offset Press, p. 95

- Nepal, Gyanmani (2007), Nepal ko Mahabharat (in Nepali) (3rd ed.), Kathmandu: Sajha, p. 314, ISBN 9789993325857

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2012), Thapa Politics in Nepal: With Special Reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806–1839, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, p. 278, ISBN 9788180698132

- Rana, Rukmani (Apr–May 1988), "B.H. Hogson as a factor for the fall of Bhimsen Thapa" (PDF), Ancient Nepal, Kathmandu (105): 13–20, retrieved Jan 11, 2013

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (1971). Regmi Research Series (PDF). 03. Regmi Research Centre.

External Links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mathabar Singh Thapa. |