Astana

| Astana Астана | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital City | |||

Clockwise from top: Astana Downtown, Kazakhstan Central Concert Hall, Khazret Sultan Mosque, L.N.Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Nazarbayev University, Palace of Peace and Reconciliation, Khan Shatyr Entertainment Center | |||

| |||

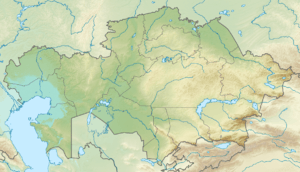

Astana Location of Astana in Kazakhstan  Astana Astana (Asia) | |||

| Coordinates: 51°10′N 71°26′E / 51.167°N 71.433°ECoordinates: 51°10′N 71°26′E / 51.167°N 71.433°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Established | in 1830 as Akmoly[1] | ||

| Renamed | in 1832 to Akmolinsk[1] | ||

| Renamed | in 1961 to Tselinograd[1] | ||

| Renamed | in 1992 to Akmola[1] | ||

| Renamed | in 1998 to Astana[2] | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Mayor–Council | ||

| • Body | City Council of Astana | ||

| • Mayor | Asset Issekeshev | ||

| Area | |||

| • Capital City | 810.2 km2 (312.8 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 347 m (1,138 ft) | ||

| Population (1 December 2017)[3] | |||

| • Capital City | 1,029,556 | ||

| • Density | 1,300/km2 (3,300/sq mi) | ||

| • Metro[4] | 1,200,000 | ||

| Time zone | UTC+6 (ALMT) | ||

| Postal code | 010000–010015[5] | ||

| Area code(s) | +7 7172[6] | ||

| ISO 3166-2 | AST[7] | ||

| License plate | 01, Z | ||

| Website |

astana | ||

Astana (Kazakh and Russian: Астана, translit. Astana; Kazakh pronunciation: [ɑstɑˈnɑ]; Russian pronunciation: [ɐstɐˈna]) is the capital city of Kazakhstan. It is located on the banks of the Ishim River in the north portion of Kazakhstan, within the Akmola Region, though administered separately from the region as a city with special status. The 2017 official estimate reported a population of 1,029,556 within the city limits, making it the second-largest city in Kazakhstan, behind Almaty.[8]

Astana became the capital city of Kazakhstan in 1997, and since then has developed economically into one of the most modernized cities in Central Asia, with futuristic-looking buildings designed by world famous architects.[9] [10]

Modern Astana is a planned city, like Brasília in Brazil, Canberra in Australia, Washington, D.C. in the United States and other planned capitals.[11] After Astana became the capital of Kazakhstan, the city cardinally changed its shape. The master plan of Astana was designed by Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa.[11] As the seat of the Government of Kazakhstan, Astana is the site of the Parliament House, the Supreme Court, the Ak Orda Presidential Palace and numerous government departments and agencies. It is home to many futuristic buildings, hotels and skyscrapers.[12][13][14] Astana also has extensive healthcare, sports and education systems.

Astana is the host city of the 8th UNWTO Global Summit on Urban Tourism held in 2019, marking the first time for Kazakhstan to hold such a high level event in the field of tourism.[15]

Etymology

Founded in 1830 as a settlement of Akmoly or Akmolinsky prikaz (Russian: Акмолинский приказ), it served as a defensive fortification for the Siberian Cossacks. In 1832 the settlement was granted a town status and renamed Akmolinsk (Russian: Акмолинск). On 20 March 1961 the city was renamed Tselinograd (Russian: Целиноград, lit. 'City of tselina') to mark the city's evolution as a cultural and administrative center of the Virgin Lands Campaign.[16] In 1992 it was renamed Akmola, the modified original name meaning "white grave".[17] On 10 December 1997 Akmola replaced Almaty as the capital of Kazakhstan. On 6 May 1998 it was renamed Astana, which means "capital city" in Kazakh.

History

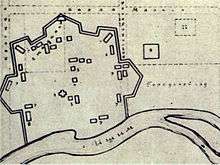

Russian Imperial era (1830–1918)

The settlement of Akmoly, also known as Akmolinsky prikaz,[1] was established on the Ishim River in 1830 as the seat of an okrug by a unit of the Siberian Cossacks headed by Fyodor Shubin.[18] The name was possibly given after a local landmark—Akmola literally means "a white grave" in Kazakh—although this theory is not universally accepted.[1] In 1832, the settlement was granted town status and named Akmolinsk.[1] The fairly advantageous position of the town was clear as early as 1863 in an abstract from the Geographic and Statistical Dictionary of the Russian Empire. It describes how picket roads and lines connected this geographic centre to Kargaly in the East, Aktau fort in the South and through Atbasar to Kokchetav in the West. In 1838, at the height of the great national and liberation movement headed by Kenesary Khan, Akmolinsk fortress was burned.[19] After the repression of the liberation movement, the fortress was rebuilt. On 16 July 1863, Akmolinsk was officially declared an uyezd town.[20] During the rapid development of the Russian capitalist market, the huge Saryarka areas were actively exploited by the colonial administration. To draft regulation governing the Kazakh Steppe the Government of the Russian Empire formed Steppe Commission in 1865.[21] On 21 October 1868, Tsar Alexander II signed a draft Regulation on governing Turgay, Ural, Akmolinsk and Semipalatinsk Oblasts.[21] In 1869, Akmolinsk external district and department were cancelled, and Akmolinsk became the centre of the newly established Akmolinsk Oblast. In 1879, Major General Dubelt proposed to build a railway between Tyumen and Akmolinsk to the Ministry of Communications of Russia. In the course of the first 30 years of its existence, the population of Akmola numbered a trifle more than 2,000 people. However, over the next 30 years the city's population increased by three times according to volosts and settlements of the Akmolinsk Oblast. In 1893, Akmolinsk was an uyezd with a 6,428 strong population, 3 churches, 5 schools and colleges and 3 factories.

Soviet era (1918–1991)

During World War II, Akmolinsk served as a route for the transport of engineering tools and equipment from evacuated plants in the Ukrainian SSR, Byelorussian SSR, and Russian SFSR located in the oblasts of the Kazakh SSR. Local industries were appointed to respond to war needs, assisting the country to provide the battle and home fronts with all materials needed. In the post-war years, Akmolinsk became a beacon of economic revival in the west of the Soviet Union ruined by the war. Additionally, many Russian-Germans were resettled here after being deported under Joseph Stalin's rule.[22]

In 1954, Northern Kazakh SSR oblasts became a territory of the Virgin Lands Campaign led by Nikita Khrushchev, in order to turn the region into a second grain producer for the Soviet Union.)[23][24] In December 1960, Central Committee made a resolution to create the Tselinniy Krai, which comprised five regions of the Northern Kazakh SSR oblasts.[25] Akmolinsk Oblast was ceased to exist as a separate administrative entity.[25] Its districts were directly subordinated to the new krai administration, and Akmolinsk became the krai capital, as well as the administrative seat of the new Virgin Lands economic region.[25] On 14 March 1961, Khrushchev proposed to rename the city to name corresponding to its role in the Virgin Lands Campaign.[26] On 20 March 1961, the Supreme Soviet of the Kazakh SSR renamed Akmolinsk to Tselinograd.[26] On 24 April 1961, the region was reconstituted as Tselinograd Oblast.[25] In the 1960s, Tselinograd was completely transformed. In 1963, work on the first three new high-rise housing districts began.[27] In addition, the city received a number of new monumental public buildings, including the Virgin Lands Palace, a Palace of Youth, a House of Soviets, a new airport, and several sports venues.[28] In 1971, the Tselinniy Krai was abolished and Tselinograd became the centre of the oblast.

Contemporary era (1991–present)

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the consequent independence of Kazakhstan, the city's original form was restored in the modified form Akmola.[1] On 6 July 1994, the Supreme Council of Kazakhstan adopted the decree "On the transfer of the capital of Kazakhstan".[29] After the capital of Kazakhstan was moved to Akmola on 10 December 1997, the city was consequently renamed Astana in 1998.[30] On 10 June 1998, Astana was presented as the capital internationally.[31] On 16 July 1999, Astana was awarded the medal and title of the City of Peace by UNESCO.[29]

Geography

%2C_satellite_image_2017-07-24.jpg)

Topography

Astana is located in central Kazakhstan on the Ishim River in a very flat, semi-arid steppe region which covers most of the country's territory. It is at 51° 10' north latitude and 71° 26' east longitude. The city encompasses 722.0 square kilometres (278.8 sq mi). The elevation of Astana is 347 metres (1,138 ft) above sea level. Astana is in a spacious steppe landscape, in the transitional area between the north of Kazakhstan and the extremely thinly settled national centre, because of the Ishim River. The older boroughs lie north of the river, whilst the new boroughs are located south of the Ishim.

Time

The time offset from the UTC used by Astana is 6 hours after UTC, or UTC+6:00. This is also used by most of Kazakhstan and Almaty.

Climate

Astana is the second-coldest capital city in the world after Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, a position formerly held by Canada's capital, Ottawa, until Astana attained capital city status in 1997.[32][33] Astana has an extreme continental climate with warm summers (featuring occasional brief rain showers) and long, very cold, dry winters. Summer temperatures occasionally reach +35 °C (95 °F) while −30 to −35 °C (−22 to −31 °F) is not unusual between mid-December and early March. Typically, the city's river is frozen over between the second week of November and the beginning of April. Astana has a well-deserved reputation among Kazakhs for its frequent high winds, the effects of which are felt particularly strongly on the fast-developing but relatively exposed Left Bank area of the city.

Overall, Astana has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb),[34] The average annual temperature in Astana is +3.5 °C (38.3 °F). January is the coldest month with an average temperature of −14.2 °C (6.4 °F) and record lowest is in January 1893's cold wave reaching temperatures down to −51.6 °C (−60.9 °F).[35] July is the hottest month with an average temperature of +20.7 °C (69.3 °F).

| Climate data for Astana | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

4.8 (40.6) |

22.1 (71.8) |

29.7 (85.5) |

35.7 (96.3) |

40.1 (104.2) |

41.6 (106.9) |

38.7 (101.7) |

36.2 (97.2) |

26.7 (80.1) |

18.5 (65.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

41.6 (106.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −9.9 (14.2) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

20.2 (68.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.2 (77.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

10.0 (50) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

8.9 (48) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −14.2 (6.4) |

−14.1 (6.6) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

5.2 (41.4) |

13.9 (57) |

19.5 (67.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

4.6 (40.3) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−12.1 (10.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −18.3 (−0.9) |

−18.5 (−1.3) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

7.9 (46.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.0 (59) |

12.8 (55) |

6.6 (43.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−8.9 (16) |

−16.1 (3) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −51.6 (−60.9) |

−48.9 (−56) |

−38.0 (−36.4) |

−27.7 (−17.9) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−2.2 (28) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−25.3 (−13.5) |

−39.2 (−38.6) |

−43.5 (−46.3) |

−51.6 (−60.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 16 (0.63) |

15 (0.59) |

18 (0.71) |

21 (0.83) |

35 (1.38) |

37 (1.46) |

50 (1.97) |

29 (1.14) |

22 (0.87) |

27 (1.06) |

28 (1.1) |

22 (0.87) |

320 (12.6) |

| Average rainy days | 2 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 106 |

| Average snowy days | 25 | 23 | 19 | 6 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 18 | 24 | 124 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78 | 77 | 79 | 64 | 54 | 53 | 59 | 57 | 59 | 68 | 80 | 79 | 67 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 103 | 147 | 192 | 238 | 301 | 336 | 336 | 294 | 230 | 136 | 100 | 94 | 2,507 |

| Source #1: Pogoda.ru.net[35] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[36] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1989 | 281,252 | — |

| 1999 | 326,900 | +16.2% |

| 2002 | 493,100 | +50.8% |

| 2010 | 649,139 | +31.6% |

| 2016 | 872,655 | +34.4% |

Population

As of September 2017, the population of Astana was 1,029,556;[3] over double the 2002 population of 493,000.[37]

The ethnic makeup of the city's population as of September 4, 2014 was:

.jpg)

Many argue that a drive to attract ethnic Kazakhs northward was the key factor in shifting the capital, which was officially put down to lack of space for expansion in the former capital, Almaty, and its location in an earthquake zone. Astana would also be 'closer to the industrial centre of Kazakhstan' than Almaty.[38]

According to the 1999 Census, 40.5% of the population was Russian, 5.7% Ukrainian, 3.0% German, 2.6% Tatar, 1.8% Belarusian and 0.8% Polish. But at 41.8%, Kazakhs outnumbered Russians and formed the largest ethnic group, while Ingush and Korean each accounted for 0.6%. Others, mostly Uzbeks, accounted for 3.8%.

In 1989, Astana had a population of 281,000. The ethnic mix was about 30% Kazakh and 70% Russian, Ukrainian and German.[39]

By 2007, Astana's population had more than doubled since becoming the capital, to over 600,000, and it topped 1 million in 2017. Migrant workers—legal and illegal—have been attracted from across Kazakhstan and neighbouring states such as Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, and Astana is a magnet for young professionals seeking to build a career. This has changed the city's demographics, bringing more ethnic Kazakhs to a city that formerly had a Slavic majority. Astana's ethnic Kazakh population has risen to some 60%, up from 17% in 1989.[40] According to preliminary figures, Astana had 700,000 inhabitants in late 2007.

Religion

Islam is the predominant religion of the city. Other religions practiced in Astana are Christianity (primarily Russian Orthodox, Roman Catholicism, and Protestantism), Judaism, and Buddhism.[41]

The Palace of Peace and Reconciliation was specially constructed in 2006 to host the Congress of Leaders of World and Traditional Religions. It contains accommodations for different religions: Judaism, Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism and other faiths. The pyramid-shaped building would express the spirit of Kazakhstan, where cultures, traditions and representatives of various nationalities coexist in peace, harmony and accord.

Metropolitan area

The metropolitan area centred upon Astana includes the Arshaly, Shortandy, Tselinograd and (partially) Akkol District districts of Akmola Region. The area contains 1.2 million people.[4]

Economy

Astana's economy is based on trade, industrial production, transport, communication and construction. The city's industrial production is mainly focused on producing building materials, foodstuff and mechanical engineering.

The Astana International Financial Center (AIFC) will open in July 2018 to become a hub for financial services in Central Asia.[42]

Astana is the headquarters of state-owned corporations such as Samruk-Kazyna, Kazakhstan Temir Zholy, KazMunayGas, KazTransOil, Kazatomprom, KEGOC, Kazpost and Kazakhtelecom.

The shift of the capital has given it a powerful boost to Astana's economic development. The city's high economic growth rate has attracted numerous investors. In the 16 years since Astana became the capital, the volume of investments has increased by almost 30 times, the gross regional product has increased by 90 times,[43] and industrial output has increased by 11 times. The city's Gross Regional Product makes up about 8.5 percent of the republic's Gross domestic product.[44]

The Astana – New City special economic zone was established in 2001 to help develop industry and increase the attractiveness of the city to investors.[45] The SEZ plans to commission five projects worth 20 billion KZT (around $108 million) in the Industrial Park #1 in 2015.[45] The projects include construction of a plant for production of diesel engines, a fast food complex, temporary storage warehouses and a business centre, a furniture factory, and production of military and civil engineering machinery.[45] The new Astana International Financial Centre is due to launch on 1 January 2018.

Astana's administration is promoting the development of small and medium-sized businesses through the cooperation of the Sovereign Welfare Fund Samruk-Kazyna and National Economic Chamber. Support is provided by a special program of crediting.[46] As a result, the number of small and medium-sized businesses increased by 13.7% to over 96,000 compared to the previous year as of July 1, 2015.[47] In addition, the number of people employed in small and medium-sized business increased by 17.8% to over 234,000 people as of April 1, 2015.[47]

Astana was included in the list of top 21 intelligent communities of the world, according to the report released by the Intelligent Community Forum in October 2016. The rating list includes the cities, regions and communities which use digital instruments for construction of local economy and society.[48]

Diplomacy Platform

Astana has become an platform for high-profile diplomatic talks and summits on critical global issues. Astana has hosted multiple rounds of talks between the Assad regime and Syrian opposition.[49] The 12th Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization (WTO) is to be held there in 2020. Beginning in 2003, Astana has hosted the Congress on World and Traditional Religions, which is a diverse gathering of religious leaders to discuss religious harmony and ending terrorism and extremism. [50]

Cityscape

.jpg)

.jpg)

Astana is subdivided into three districts. Almaty District was created on 6 May 1998 by presidential decree. The district's territory encompasses an area of 21,054 hectares (52,030 acres; 81.29 square miles) with a population of 375,938 people. The district has five villages. Yesil District, which is also called left bank of the city, was created on 5 August 2008 by presidential decree. The district's territory encompasses an area of 31,179 ha (77,040 acres; 120.38 sq mi) with a population of 119,929 people. Saryarka District was created on 6 May 1998 by presidential decree. The district's territory encompasses an area of 19,202 ha (47,450 acres; 74.14 sq mi) with a population of 339,286 people.

In April 1998, the Government of Kazakhstan asked architects and urban planners of international renown to participate in a design competition for the new capital. On 6 October 1998, Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa was awarded the First Prize.[51] Summary of Kurokawa's Proposal, since the 1960s, pleaded for the paradigm shift from the age of the machine principle to the age of life principle.[51] His work is the embodiment of Metabolism and symbiosis, which are the two most important concepts of the age of life principle.[51] Kurokawa's proposal aimed to preserve and redevelop the existing city, and create a new city at the south and the east sides of the Ishim River, enabling the Symbiosis of the History and the Future.[51]

North of the railway line, which crosses Astana in an east-west direction, are industrial and poorer residential areas. Between the railway line and the Ishim river is the city centre, where at present intense building activity is occurring. To the west and east are more elevated residential areas with parks and the new area of government administration to the south of the Ishim River. Here many large building projects are under way; for example, the construction of a diplomatic quarter, and a variety of different government buildings. By 2030, these quarters are to be completed. Astana's current chief planner, Vladimir Laptev, wants to build a Berlin in a Eurasian style. He has stated that a purely administrative capital such as Canberra is not one of his goals.

Panoramic view

Sport

The city has a variety of sporting teams. The major association football team is the FC Astana of the Kazakhstan Premier League. Founded in 2009, Astana won four league titles, three Kazakhstan Cups and two Kazakhstan Super Cups.[52] Their home ground is the Astana Arena, which is also serves as a home for the Kazakhstan national football team and the FC Bayterek. The FC Bayterek is a member of the Kazakhstan First Division. They were founded in 2012, to develop youth football.[53] The FC Astana-1964 is based in the Kazhymukan Munaitpasov Stadium and plays in the Astana Municipal Football League. The club's most successful years were 2000s, when they won 3 league titles.

Astana is home to several professional ice hockey teams. The Barys Astana, a founding member of the Kontinental Hockey League in 2008 and based in the Barys Arena.[54] The Nomad Astana and HC Astana play in the Kazakhstan Hockey Championship. The Snezhnye Barsy of the Junior Hockey League is a junior team of the Barys Astana.[55] Astana annually hosts the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan's Cup ice hockey tournament.[56]

The Astana Pro Team, founded in 2007, participates in the UCI World Tour.[57] The team is one of the most successful cycling teams of recent years, winning several grand tours. The BC Astana of the VTB United League and the Kazakhstan Basketball League is the only professional basketball team in Astana.[58] It is the most successful basketball team in Kazakhstan with three Kazakhstan Basketball League titles and four Kazakhstan Basketball Cups.[58] Its home arena is the Saryarka Velodrome, which is mainly used for track cycling events.[58] The Saryarka Velodrome hosted the UCI Track Cycling World Cup stage in 2011.[59] The Astana Presidential Sports Club was founded in 2012, to combine the main sports teams in Astana.[60] The organization is supported by Sovereign Wealth Fund Samruk-Kazyna.[61] The 2011 Asian Winter Games were partly held in the capital. The Alau Ice Palace, hosted the 2015 World Sprint Speed Skating Championships.[62] The President's Cup tennis tournament is annually held at the Daulet National Tennis Centre.[63]

Education

Astana has many universities and junior colleges. as of the 2013/2014 academic year, Astana had a total enrollment of 53,561 students in its 14 higher educational institutions, a 10% increase from the prior year.[64] The L.N.Gumilyov Eurasian National University is the biggest university in Astana with 16,558 students and 1,678 academic staff.[65] It was founded as the result of merging the Akmola Civil Engineering Institute and Akmola Pedagogical Institute on 23 May 1996.[66] The oldest university in Astana is the S.Seifullin Kazakh Agro Technical University founded in 1957.[67] Nazarbayev University is an autonomous research university founded in 2010 in partnership with some of the world's top universities.[68] The Kazakh University of Economics, Finance and International Trade is an economic institution in Astana.[69] The Kazakh Humanities and Law Institute is a law university founded by initiative of Ministry of Justice in 1994.[70] The Astana Medical University was the only medical school in Astana until the opening of the School of Medecine at Nazarbayev University in 2014.[71] The Kazakh National University of Arts is the premier music school and has provided Astana with highly qualified professional specialists in the field of Arts.[72]

Astana schools enrolls about 103,000 students across 83 schools, including 71 state schools and 12 private schools.[73][74] The Miras International School, established 1999, was the first private high school established in Astana.[75] The Haileybury Astana school was established in 2011, as a branch of the Haileybury and Imperial Service College, an independent school in The United Kingdom. The Astana Kazakh-Turkish High Schools are run by the International KATEV foundation. In Astana, there are Kazakh-Turkish High Boarding Schools for gifted boys and girls, separately and the Nurorda International School.[76] Astana hosts two Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools (NIS), including School of Physics and Mathematics and International Baccalaureate world school.[77] The QSI International School of Astana is an international school that provides an American curriculum to its students. The school is a branch of the Quality Schools International that started in the Middle East.[78]

Transportation

Public transport

Public transport in Astana consists of buses and share taxis. Over 720,000 people use public transport daily.[79] There are over 40 bus lines served by more than 1000 vehicles, with over 3000 people working in the public transport sector.[80] Just like buses, share taxis have their own predefined routes and work on a shared basis. There are nine share taxi routes in total. In 2011, Akimat of Astana established a company to implement a series of changes and programmes in the metropolis known as the "New transport system of Astana".[81] As the part of these programmes, Bus rapid transit (BRT) lines are expected to start operating in Astana in 2016.[82] Astana Light Metro is a proposed light rail system.[83] Astana also has air taxi service[84] and the modern Astana Bike bicycle-sharing system.

Air

Astana International Airport (IATA: TSE, ICAO: UACC), located 17 kilometres (11 mi) south-east of the city centre, is the main gateway for the city's domestic and international civilian air traffic.[85] It is the second-busiest airport in Kazakhstan, with 2,960,181 passengers passing through it in 2014.[86] The airport hosts 13 airlines operating regular passenger flights inside the country and internationally.[87] Air Astana maintains its second-largest hub at the airport.[88] An expected 50% increase in passenger traffic by 2017 has spurred construction of a new terminal with an area of about 40,000 square metres (430,000 sq ft).[89][90]

Railway and roads

Astana is located in the centre of the country, serving as a well-positioned transport node for rail and automotive networks.[91]

Astana railway station is the city's main railway station and serves approximately 7,000 people each day. A new railway station, Nurly Zhol was built during the Expo 2017 event with a customer capacity of 12,000. Tulpar Talgo is a daily express train to Almaty.[92] Short-term plans include construction of a new railway station in the industrial district; in the vicinity of CHPP-3 a new terminal will be erected for freight cars.[93]

M-36 Chelyabinsk-Almaty and A-343 Astana-Petropavlovsk highways are routed through the city. The strategic geographical positioning of Astana allows the city to serve as a transport and reload centre for cargoes formed at adjacent stations in the area.

Expo 2017

On 1 July 2010, at the 153rd General Assembly of Bureau International des Expositions held in Paris, representatives from Astana presented the city's bid to host the Specialised Expo 2017.[94][95][96] Kazakhs concept for this exhibition relates to the impact of energy and social on the modern world. The theme of the Astana Expo was "Future Energy".[97]

Expo 2017 opened to much fanfare on June 10, with heads of state from 17 different nations in attendance. The two-millionth visitor was registered on August 7. It is the first world's fair to be held in Central Asia and its central pavilion, Nur Alem, is the largest spherical building in the world.

More than 4 million people visited Expo 2017 in Astana, two times more than was expected. Recently it was announced that Expo pavilion will be opened again on 11 November. Entry will be free for all the visitors. The only places that will require additional fees for entry are "Nur Alem" and centre of art.

Sister cities

Astana maintains official partnerships with 18 cities. Astana's twin towns and sister cities are:

- 1994

- 1996

- 1996

- 1996

- 1998

- 2001

- 2002

- 2004

- 2004

- 2004

- 2004

- 2005

- 2006

- 2009

- 2010

- 2011

- 2013

- 2014

- 2014

Smart City initiative

The Smart Astana project is an initiative developed by the Astana city administration that incorporates technology-driven solutions in various sectors, like hospitals, schools, the ticket booking system and street lighting.[117] These projects run on an interconnected application, The Smart Astana.[117]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pospelov 1993, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ "The history of Astana". Akimat of Astana. 19 January 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Об изменении численности населения Республики Казахстан с начала 2017 года до 1 декабря 2017 года (Citizenship of the Republic of Kazakhstan ... to 1 December 2017)" (in Russian). 4 January 2018.

- 1 2 Жулмухаметова, Жадра (31 October 2017). "Чиновники работают над тем, чтобы уместить в Астане два миллиона человек" (in Russian).

- ↑ "Postal Code for Astana, Kazakhstan". Postal Codes Database. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan Country Codes". CountryCallingCodes.com. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ↑ "ISO Subentity Codes for Kazakhstan". GeoNames.org. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ "Astana, a city of modern structures". Jakarta Times.

- ↑ "Astana, Kazakhstan: the space station in the steppes". The Guardian.

- 1 2 "Astana, Kazakhstan: the space station in the steppes". The Guardian. 8 August 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ Steven Lee Myers (13 October 2006). "Kazakhstan's Futuristic Capital, Complete With Pyramid". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Astana, the futuristic frontier of architecture". The Guardian. 8 August 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Daisy Carrington (13 July 2012). "Astana: The world's weirdest capital city". CNN. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Astana to host UNWTO Global Summit for Urban Tourism". egemen.kz.

- ↑ The Current Digest of the Post-Soviet Press. Current Digest of the Soviet Press. 1994. p. 20.

- ↑ Paul Brummell (7 September 2018). Kazakhstan. Bradt Travel Guides; Third edition. p. 71. ISBN 978-1784770921.

- ↑ "От центра окружного приказа до столицы Казахстана" (краткий исторический обзор истории столицы) [From the centre of district order to the capital of Kazakhstan (short historical overview of the history of the capital)] (in Russian). Archive and Documentation Department of Astana. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ↑ "Revolt of 1837—1847 under the leadership of khan Kenesary". e-history.kz. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ↑ "History of Astana". e-history.kz. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ↑ S. Kurmanova. "Deportation of Volga Germans to Kazakhstan: Causes and Consequences" (PDF). e-history.kz. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ↑ Paul Brummell (7 September 2018). Kazakhstan. Bradt Travel Guides; Third edition. p. 71. ISBN 978-1784770921.

- ↑ Ian MacWilliam (20 April 1994). "In Virgin Lands, a Dream Ends". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Kozlov & Gilburd 2013, p. 293.

- 1 2 Khrushchev 2010, p. 739.

- ↑ Kozlov & Gilburd 2013, p. 295.

- ↑ Kozlov & Gilburd 2013, p. 296.

- 1 2 "Astana – the capital of the Republic of Kazakhstan". e-history.kz. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ↑ "Timeline: Kazakhstan". BBC News. 31 January 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Astana – the capital of the Republic of Kazakhstan". Official site of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ Brian White (9 January 2013). "Ulaanbaatar is the Coldest Capital". The Mongolist. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ↑ "Still the third-coldest capital, despite balmy temperatures". Canada.com. 4 January 2007. Archived from the original on 6 June 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ↑ Updated Central, South, Southeast, and Eastern Asian and Siberian Map of the Köppen climate classification system.

- 1 2 "Weather and Climate-The Climate of Astana" (in Russian). Weather and Climate. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ "Akmola (Astana) Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ "Население Астаны". www.demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ↑ Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Kazachstan. §5. Geschiedenis". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ↑ "Astana". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan's Capital Holds a Lavish Anniversary Celebration". EurasiaNet.org. 8 July 2007. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ "Religion in Astana - Astana". www.astana-hotels.net. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan: Staff Concluding Statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission". IMF.

- ↑ "Astana celebrates 16th anniversary as Kazakhstan's capital". Tengrinews.kz. 9 July 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ↑ "Poverty in Kazakhstan: Causes and Cures" (PDF). UNDP Kazakhstan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Five projects to be launched in Astana industrial park this year". The Times of Central Asia. 5 February 2015. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ "Over 170 thousand of people involved in small and medium enterprise in Astana". Akimat of Astana. 14 March 2014. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Number of small and medium-sized business entities grew by 13.7% in Astana". inform.kz.

- ↑ "The Smart21 Communities of the Year". www.intelligentcommunity.org.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan's New Capital Is Growing Up Quick". Forbes.

- ↑ "Vth Congress of Leaders of World and Traditional Religions". UNESCO.

- 1 2 3 4 Whyte 2000, p. 216.

- ↑ Достижения [Achievements] (in Russian). Astana F.C. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ ФК "Байтерек" – новый клуб из столицы [FC Bayterek – the new club from the capital] (in Russian). Total.kz. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ "Barys Astana". Kontinental Hockey League. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Snezhnye Barsy". Junior Hockey League. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Paul Bartlett (8 August 2010). "Ice Comes Early for Astana Hockey Fans". Eurasianet.org. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "UCI WorldTeams". Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI). Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 "History". BC Astana. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Preview: 2011 UCI Track World Cup Round 1". BritishCycling.org.uk. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Ilyas Omarov (4 July 2013). "Astana Presidential Sports Club Launched". The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ Paul Osborne (9 April 2014). "Astana Presidential Sports Club outlines vision to boost Kazakhstan's image". insidethegames.biz. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ Dmitry Lee (3 March 2015). "Alau Ice Palace Hosts World Sprint Skating Championship, Kazakh Skaters Fail to Reach Podium". The Astana Times. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Nazymgul Kumyspaeva. "International President's Cup tennis tournament kicked off in Astana". KazPravda.kz. Retrieved 7 October 2014. .

- ↑ "The number of university students in Astana increased by more than 10%". Akimat of Astana. 3 March 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy" В новом учебном году в ЕНУ им. Л.Н. Гумилева будут обучаться 16 558 человек [16 558 students will study in the new academic year at the L.N.Gumilyov Eurasian National University] (in Russian). Info-Tses. 31 August 2014. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ История и ЕНУ сегодня [History and ENU today] (in Russian). L.N.Gumilyov Eurasian National University. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "History of the university". S.Seifullin Kazakh Agro Technical University. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "History & Strategy". Nazarbayev University. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Kazakh University of Economics, Finance and International Trade (KazUEFIT)". EURASHE.eu. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "History of KAZGUU". Kazakh Humanities and Law Institute. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "About the University". Astana Medical University. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ "About us". Kazakh National University of Arts. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "5 new schools open doors in Astana today". Kazinform. 1 September 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "13,000 to start school this year in Astana". Kazinform. 4 August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "General information about school". Miras International School. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "About Us".

- ↑ "Intellectual schools". Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "QSI International School of Astana". Quality Schools International (QSI). Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ↑ Ainur Kuramyssova (17 December 2014). "36 Buses Added to Astana's Most Popular Routes". The Astana Times. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ↑ "Astana Public Transportation". world66.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ↑ Yusup Khassiev (17 October 2012). "Astana: an advancing city in the modern age". International Association of Public Transport. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ↑ "350 French buses working on natural gas are to be delivered in Astana in 2014". Akimat of Astana. 27 December 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "Astana rejects Light Rail Transport system in favor of rapid bus network". The Times of Central Asia. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Dmitry Lee (20 January 2015). "Astana-based Company Launches Kazakhstan's First Air Taxi Service". The Astana Times. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ Международный аэропорт Астаны [Astana International Airport] (in Russian). Aeroport.kz. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ "Passenger traffic". Astana International Airport. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "General information". Astana International Airport. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "No People's IPO for Air Astana in near future: Samruk Kazyna". Tengrinews.kz. 31 July 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ "Passenger traffic in Astana airport to increase to 5 million passengers a year by 2017". Akimat of Astana. 26 February 2013. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "New Passenger Terminal will be created after the Capitals Airport Reconstruction". Akimat of Astana. 6 November 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ ""Astana" station". Kazakhstan Temir Zholy. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "Kazakh-Spanish trains to become more comfortable". Tengrinews.kz. 28 January 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ "Astana will construct new railroad station for EXPO-2017". Tengrinews.kz. 17 January 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ "Future energy – solutions for tackling mankind's greatest challenge". BIE.

- ↑ "Expo2017: Future Energy and Impact on our Lives". Astana Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014.

- ↑ "Vision". expo2017astana.com. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016.

- ↑ "APCO Worldwide to Drive Energy Innovation Future as Chief Organizing Partner for USA Pavilion at Expo 2017".

- ↑ "Astana city". OrexCa. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "Partner Cities". Gdańsk Official Website. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Saint Petersburg to welcome Days of Astana Culture". Kazinform. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Tbilisi Sister Cities". Tbilisi Municipal Portal. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Riga's Twin Cities". Municipal Portal of Riga. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sister Cities of Ankara". Greater Municipality of Ankara. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Miasta partnerskie Warszawy" [Twin cities of Warsaw] (in Polish). City of Warsaw. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (11 June 2004). "Agreement on establishment of bilateral relations between the Akimat of Astana City of the Republic of Kazakhstan and the City of Bangkok of Kingdom Thailand" (PDF). Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ Rafik Valiev (18 September 2014). "Archived copy" 10 лет исполнится побратимству городов Астаны и Казани [Astana and Kazan celebrates 10-years anniversary of sister cities status] (in Russian). VechAstana.kz. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "About Manila: Sister Cities". City of Manila. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ↑ "International Cooperation: Sister Cities". Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 10 December 2007. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- ↑ "Twin City Agreement". Greater Amman Municipality. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sister Cities". Beijing Government. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ↑ Ilia Lobster (9 September 2009). "Astana-Hanoi: horizons of cooperation". KazPravda.kz. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ufa and Astana Signed Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation". Ufa City Municipality. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Бишкек и Астана — города-побратимы [Bishkek and Astana — Sister Cities] (in Russian). Official website of City Hall of Bishkek. 12 September 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Astana and Finnish Oulu become twin-cities". Tengrinews.kz. 19 April 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Astana and Nice established twin relations". Akimat of Astana. 5 July 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Declaration of intent signed by Akim of Astana and Mayor of Croatias capital". Akimat of Astana. 4 July 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Astana moving closer to becoming smart city". astanatimes.com.

Further reading

- Pospelov, Evgeni (1993). Имена городов: вчера и сегодня (1917–1992). Топонимический словарь [City Names: Yesterday and Today (1917–1992). Toponymic Dictionary]. Русские словари.

- Kozlov, Denis; Gilburd, Eleonory (2013). The Thaw: Soviet Society and Culture during the 1950s and 1960s. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442644601.

- Khrushchev, Sergei (2010). Никита Хрущев. Реформатор Никита Хрущев. Реформатор [Nikita Khrushchev. Reformer]. Время. ISBN 9785969105331.

- Mallone, Laura (23 September 2016). "The Eccentric Autocrat Who Spent Billions Inventing A City". Wired.

- Whyte, Andy (2000). Kisho Kurokawa, Architect and Associates: Selected and Current Works. Images Publishing. ISBN 9781864700190.

- Vale, Lawrence (2014). Architecture, Power and National Identity. Routledge. ISBN 9781134729210.