Gdańsk

| Gdańsk | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| |||

|

Motto(s): Nec Temere, Nec Timide (Neither rashly, nor timidly) | |||

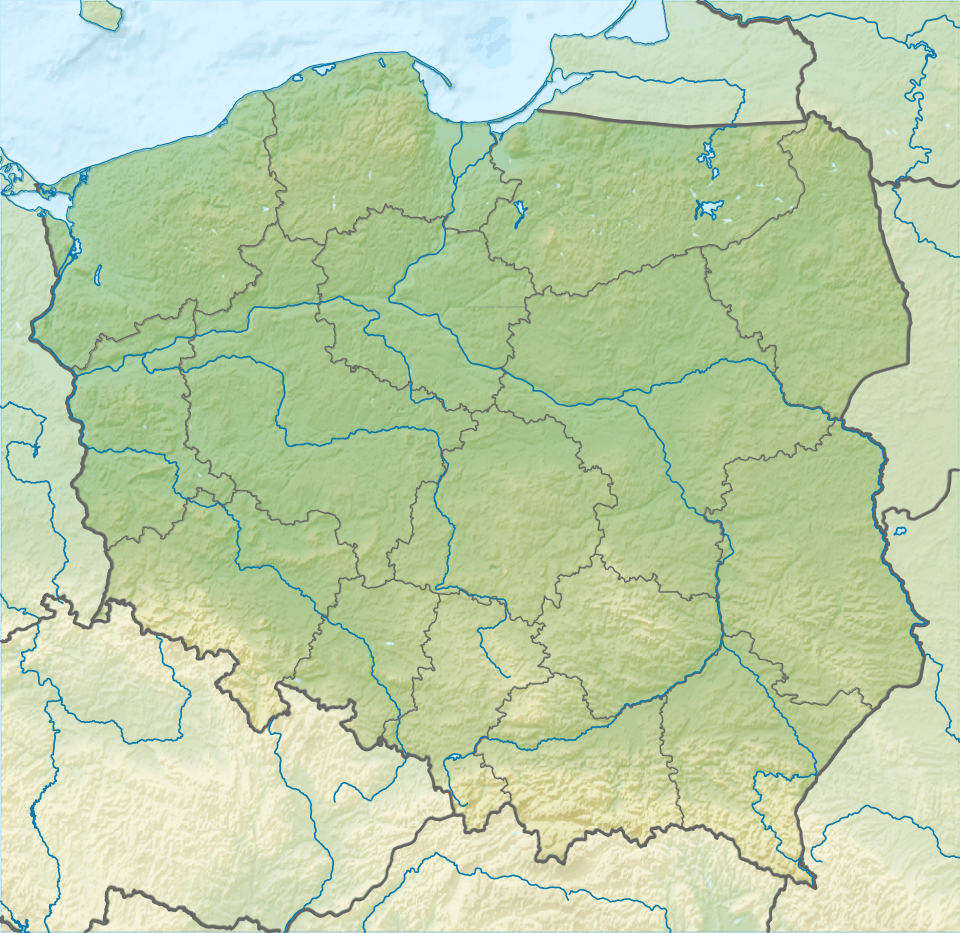

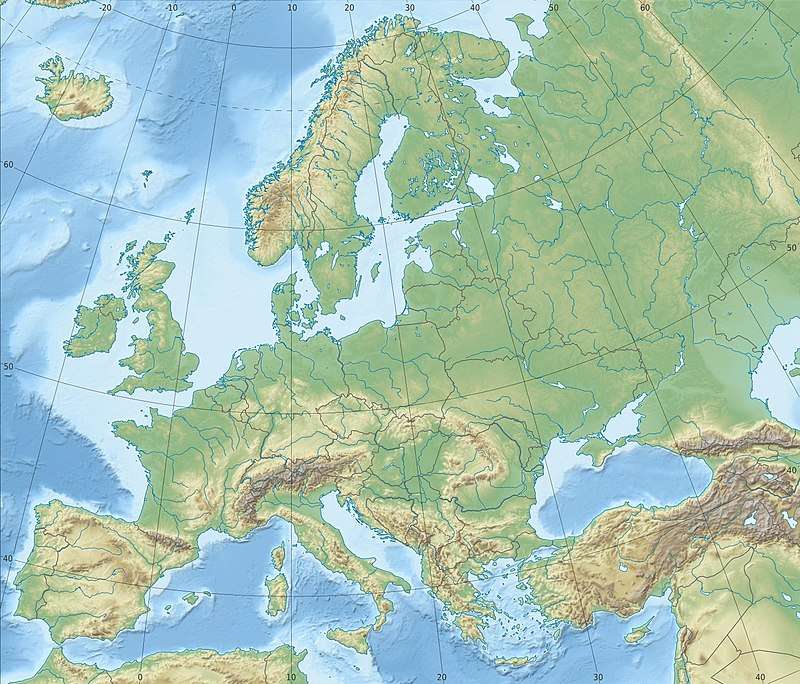

Gdańsk Location of Gdansk in Poland  Gdańsk Gdańsk (Europe) | |||

| Coordinates: 54°22′N 18°38′E / 54.367°N 18.633°ECoordinates: 54°22′N 18°38′E / 54.367°N 18.633°E | |||

| Country | Poland | ||

| Voivodeship | Pomeranian | ||

| County | city county | ||

| Established | 10th century | ||

| City rights | 1263 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Paweł Adamowicz (PO) | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 262 km2 (101 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2016) | |||

| • City |

463,754 | ||

| • Metro | 1,080,700 | ||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||

| Postal code | 80-008 to 80–958 | ||

| Area code(s) | +48 58 | ||

| Car plates | GD | ||

| Website | gdansk.pl | ||

Gdańsk (/ɡəˈdɑːnsk, ![]()

![]()

The city lies on the southern edge of Gdańsk Bay (of the Baltic Sea), in a conurbation with the city of Gdynia, spa town of Sopot, and suburban communities, which together form a metropolitan area called the Tricity (Trójmiasto), with a population approaching 1.4 million. Gdańsk itself has a population of 460,427 (December 2012), making it the largest city in the Pomerania region of Northern Poland.

Gdańsk is the capital of Gdańsk Pomerania and the largest city of Kashubia. With its origins as a Polish stronghold erected in the 980s by Mieszko I of Poland, the city's history is complex, with periods of Polish rule, periods of Prussian or German rule, and periods of autonomy or self-rule as a "free city". In the early-modern age Gdańsk was a royal city of Poland. It was considered the wealthiest and the largest city of Poland, prior to the 18th century rapid growth of Warsaw. Between the world wars, the Free City of Danzig was in a customs union with Poland and was located between German East Prussia and the so-called Polish Corridor.

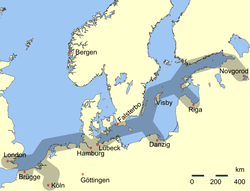

Gdańsk lies at the mouth of the Motława River, connected to the Leniwka, a branch in the delta of the nearby Vistula River, which drains 60 percent of Poland and connects Gdańsk with the Polish capital, Warsaw. Together with the nearby port of Gdynia, Gdańsk is also a notable industrial center. In the late Middle Ages it was an important seaport and shipbuilding town and, in the 14th and 15th centuries, a member of the Hanseatic League.

In the interwar period, owing to its multi-ethnic make-up and history, Danzig lay in a disputed region between Poland and the Weimar Republic, and later Nazi Germany. The city's ambiguous political status was exploited, furthering tension between the two countries, which would ultimately culminate in the Invasion of Poland and the first clash of the Second World War just outside the city limits. In the 1980s it would become the birthplace of the Solidarity movement, which played a major role in bringing an end to Communist rule in Poland and helped precipitate the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Gdańsk is home to the University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk University of Technology, the National Museum, the Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre, the Museum of the Second World War, Polish Baltic Philharmonic and the European Solidarity Centre. The city also hosts St. Dominic's Fair, which dates back to 1260, and is regarded as one of the biggest trade and cultural events in Europe.[3]

Names

The city's name is thought to originate from the Gdania River,[4] the original name of the Motława branch on which the city is situated. The name of a settlement was recorded after St. Adalbert's death in AD 997 as urbs Gyddanyzc[5] and later was written as Kdanzk in 1148, Gdanzc in 1188, Danceke[6] in 1228, Gdansk in 1236,[7] Danzc in 1263, Danczk in 1311,[8] Danczik in 1399,[5][9] Danczig in 1414, Gdąnsk in 1656. In Polish the modern name of the city is pronounced [ɡdaɲsk] (![]()

![]()

The city's Latin name may be given as either Gedania, Gedanum or Dantiscum; the variety of Latin names reflects the mixed influence of the city's Polish, German and Kashubian heritage. Other former spellings of the name include Dantzig, Dantsic and Dantzic.

Ceremonial names

On special occasions the city is also referred to as "The Royal Polish City of Gdańsk" (Polish Królewskie Polskie Miasto Gdańsk, Latin Regia Civitas Polonica Gedanensis, Kashubian Królewsczi Polsczi Gard Gduńsk).[10][11][12] In the Kashubian language the city is called Gduńsk. Kashubians also use the name "Our Capital City Gduńsk" (Nasz Stoleczny Gard Gduńsk) or "The Kashubian Capital City Gduńsk" (Stoleczny Kaszëbsczi Gard Gduńsk).

History

Early Poland

The first written record thought to refer to Gdańsk is the vita of Saint Adalbert. Written in 999, it describes how in 997 Saint Adalbert of Prague baptised the inhabitants of urbs Gyddannyzc, "which separated the great realm of the duke [i.e. Boleslaw the Brave of Poland] from the sea."[13] No further written sources exist for the 10th and 11th centuries.[13] Based on the date in Adalbert's vita, the city celebrated its millennial anniversary in 1997.[14]

Archaeological evidence for the origins of the town was retrieved mostly after World War II had laid 90 percent of the city center in ruins, enabling excavations.[15] The oldest seventeen settlement levels were dated to between 980 and 1308.[14] It is generally thought that Mieszko I of Poland erected a stronghold on the site in the 980s, thereby connecting the Polish state ruled by the Piast dynasty with the trade routes of the Baltic Sea.[16] Traces of buildings and housing from 10th century have been found in archaeological excavations of the city[17].

Pomeranian Poland

The site was ruled on behalf of Poland by the Samborides' duchy and consisted of a settlement at the modern Long Market, craftsmen settlements along the Old Ditch, German merchant settlements around the St Nicolas church and the old Piast stronghold.[18] In 1186, a Cistercian monastery was set up in nearby Oliwa, which is now within the city limits. In 1215, the ducal stronghold became the centre of a Pomerelian splinter duchy. At that time the area of the later city comprised different villages. At least since 1224/25 a German market settlement with merchants from Lübeck existed in the area of today's Long Market.[19] In 1224/25, merchants from Lübeck were invited as "hospites" (immigrants with specific privileges) but were soon forced to leave by Swantopolk II of the Samborides in 1238 during a war between Swantopolk and the Teutonic Knights, during which Lübeck supported the latter. Migration of merchants to the town resumed in 1257.[20] Significant German influence did not appear until the 14th century, after the takeover of the city by the Teutonic Knights.[21] At latest in 1263 Pomerelian duke, Swantopolk II. granted city rights under Lübeck law to the emerging market settlement.[19] It was an autonomy charter similar to that of Lübeck, which was also the primary origin of many settlers.[18] In a document of 1271 the Pomerelian duke Mestwin II. addressed the Lübeck merchants settled in the city as his loyal citizens from Germany.[22][23]

In 1300, the town had an estimated population of 2,000.[24] While overall the town was not a very important trade centre at that time, it had some relevance in the trade with Eastern Europe.[24] Low on funds, the Samborides lent the settlement to Brandenburg, although they planned to take the city back and give it to Poland. Poland threatened to intervene, and Brandenburg left the town. Subsequently, the city was taken by Danish princes in 1301. The Teutonic Knights were hired by the Polish nobles to clear out the Danes.

Teutonic Knights

In 1308, the town was taken by Brandenburg and the Teutonic Knights restored order. Subsequently, the Knights took over control of the town. Primary sources record a massacre carried out by the Teutonic Knights on the local population,[25] of 10,000 people, but the exact number killed is subject of dispute in modern scholarship.[26] Some authors accept the number given in the original sources,[27] while others consider 10,000 to have been a medieval exaggeration, although scholarly consensus is that a massacre of some magnitude did take place.[26] The events were used by the Polish crown to condemn the Teutonic Knights in a subsequent papal lawsuit.[26][28]

The knights colonised the area, replacing local Kashubians and Poles with German settlers.[27] In 1308, they founded Osiek Hakelwerk near the town, initially as a Slavic fishing settlement.[25] In 1340, the Teutonic Knights built a large fortress, which became the seat of the knights' Komtur.[29] In 1346 they changed the Town Law of the city, which then consisted only of the Rechtstadt, to Kulm law.[30] In 1358, Danzig joined the Hanseatic League, and became an active member in 1361.[31] It maintained relations with the trade centers Bruges, Novgorod, Lisboa and Sevilla.[31] Around 1377, the Old Town was equipped with city rights as well.[32] In 1380, the New Town was founded as the third, independent settlement.[25]

After a series of Polish-Teutonic Wars, in the Treaty of Kalisz (1343) the Order had to acknowledge that it would hold Pomerelia as an alm from the Polish Crown. Although it left the legal basis of the Order's possession of the province in some doubt, the city thrived as a result of increased exports of grain (especially wheat), timber, potash, tar, and other goods of forestry from Prussia and Poland via the Vistula River trading routes, although after its capture, the Teutonic Knights tried to actively reduce the economic significance of the town. While under the control of the Teutonic Order German migration increased. The Order's religious networks helped to develop Danzig's literary culture.[33] A new war broke out in 1409, ending with the Battle of Grunwald (1410), and the city came under the control of the Kingdom of Poland. A year later, with the First Peace of Thorn, it returned to the Teutonic Order.[34]

Kingdom of Poland

In 1440, the city participated in the foundation of the Prussian Confederation which was an organisation opposed to the rule of the Teutonic Knights. This led to the Thirteen Years' War against the Teutonic Monastic State of Prussia (1454–1466). On 25 May 1457 the city gained its rights and independence as an autonomous city.[35][36]

On 15 May 1457, Casimir IV of Poland granted the town the Great Privilege, after he had been invited by the town's council and had already stayed in town for five weeks.[37] With the Great Privilege, the town was granted full autonomy and protection by the King of Poland.[38] The privilege removed tariffs and taxes on trade within Poland, Lithuania and Ruthenia (present day Belarus and Ukraine) and conferred on the town independent jurisdiction, legislation and administration of her territory, as well as the right to mint its own coin.[37] Furthermore, the privilege united Old Town, Osiek and Main Town, and legalised the demolition of New Town, which had sided with the Teutonic Knights.[37] By 1457, New Town was demolished completely, no buildings remained.[25]

Gaining free and privileged access to Polish markets, the seaport prospered while simultaneously trading with the other Hanseatic cities. After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466) with the Teutonic Monastic State of Prussia the warfare between the latter and the Polish crown ended permanently. After the Union of Lublin between Poland and Lithuania in 1569 the city continued to enjoy a large degree of internal autonomy (cf. Danzig Law). Being the largest and one of the most influential cities of Poland, it enjoyed voting rights during the royal election period in Poland.

In 1569 a Mennonite Church was founded here.

In the 1575 election of a king to the Polish throne, Danzig supported Maximilian II against Stephen Báthory. It was the latter who eventually became monarch but the city, encouraged by the secret support of Denmark and Emperor Maximilian, shut its gates against Stephen. After the Siege of Danzig (1577), lasting six months, the city's army of 5,000 mercenaries was utterly defeated in a field battle on 16 December 1577. However, since Stephen's armies were unable to take the city by force, a compromise was reached: Stephen Báthory confirmed the city's special status and her Danzig Law privileges granted by earlier Polish kings. The city recognised him as ruler of Poland and paid the enormous sum of 200,000 guldens in gold as payoff ("apology").

Around 1640, Johannes Hevelius established his astronomical observatory in the Old Town. Polish King John III Sobieski regularly visited Hevelius numerous times.

Beside the large numbers of German-speakers, whose elites sometimes distinguished their German dialect as Pomerelian,[41] the city was home to a large number of Polish-speaking Poles, Jewish Poles, Latvian speaking Kursenieki, Flemings and Dutch. In addition, a number of Scots took refuge or migrated to and received citizenship in the city. During the Protestant Reformation, most German-speaking inhabitants adopted Lutheranism. Due to the special status of the city and significance within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the city inhabitants largely became bi-cultural sharing both Polish and German culture and were strongly attached to the traditions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[42]

The city suffered a last great plague and a slow economic decline due to the wars of the 18th century. As a stronghold of Stanisław Leszczyński's supporters during the War of the Polish Succession, it was taken by the Russians after the Siege of Danzig in 1734.

The Danzig Research Society founded in 1743 was one of the first of its kind.

Prussia and Germany

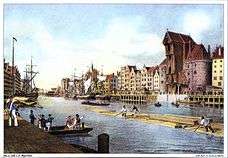

.jpg)

Danzig was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia in 1793,[43] in the Second Partition of Poland. An attempt of student uprising against Prussia led by Gottfried Benjamin Bartholdi was crushed quickly by the authorities in 1797.[44][45][46] During the era of Napoleon the city became a free city in the period extending from 1807 to 1814.

In 1815, after France's defeat in the Napoleonic Wars, it again became part of Prussia[43] and became the capital of Regierungsbezirk Danzig within the province of West Prussia. The city's longest serving president was Robert von Blumenthal, who held office from 1841, through the revolutions of 1848, until 1863. With the unification of Germany under Prussian hegemony, the city became part of Imperial Germany (the German Empire) in 1871, and remained so until 1919, after Germany's defeat in World War I.

Inter-war years and World War II

.jpg)

When Poland regained its independence after World War I with access to the sea as promised by the Allies on the basis of Woodrow Wilson's "Fourteen Points" (point 13 called for "an independent Polish state", "which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea"), the Poles hoped the city's harbour would also become part of Poland. However, since Germans formed a majority in the city, with Poles being a minority,[47] the city was not placed under Polish sovereignty. Instead, in accordance with the terms of the Versailles Treaty, it became the Free City of Danzig (German: Freie Stadt Danzig), an independent quasi-state under the auspices of the League of Nations with its external affairs largely under Polish control. Poland's rights also included free use of the harbour, a Polish post office, a Polish garrison in Westerplatte district, and customs union with Poland. This led to a considerable tension between the city and the Republic of Poland. The Free City had its own constitution, national anthem, parliament (Volkstag), and government (Senat). It issued its own stamps as well as its currency, the Danzig gulden.

In the early 1930s the local Nazi Party capitalised on pro-German sentiments and in 1933 garnered 50% of vote in the parliament. Thereafter, the Nazis under Gauleiter Albert Forster achieved dominance in the city government, which was still nominally overseen by the League of Nations' High Commissioner. The German government officially demanded the return of Danzig to Germany along with an extraterritorial (meaning under German jurisdiction) highway through the area of the Polish Corridor for land-based access from the rest of Germany. Hitler used the issue of the status of the city as a pretext for attacking Poland and on May 1939, during a high level meeting of German military officials explained to them: "It is not Danzig that is at stake. For us it is a matter of expanding our Lebensraum in the east", adding that there will be no repeat of the Czech situation, and Germany will attack Poland at first opportunity, after isolating the country from its Western Allies.[48][49][50][51][52] After the German proposals to solve the three main issues peacefully were refused and the sixteen point proposal has been undermined by the British Government (Navy Minister Cooper), German-Polish relations rapidly deteriorated. Germany attacked Poland on 1 September after having signed a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union (this includes the Secret Part with the upcoming treatment of the Baltic States) in late August and after postponing the attack three times due to needed time for diplomatic, peaceful solutions.

The German attack began in Danzig, with a bombardment of Polish positions at Westerplatte by the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein, and the landing of German infantry on the peninsula. Outnumbered Polish defenders at Westerplatte resisted for seven days before running out of ammunition. Meanwhile, after a fierce day-long fight (1 September 1939), defenders of the Polish Post office were tried and executed then buried on the spot in the Danzig quarter of Zaspa in October 1939. In 1998 a German court overturned their conviction and sentence.

The city was officially annexed by Nazi Germany and incorporated into the Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia. About 50 percent of members of the Jewish Community of Danzig had left the city within a year after a Pogrom in October 1937,[53] after the Kristallnacht riots in November 1938 the community decided to organize its emigration[54] and in March 1939 a first transport to Palestine started.[55] By September 1939 barely 1,700 mostly elderly Jews remained. In early 1941, just 600 Jews were still living in Danzig, most of whom were later murdered in the Holocaust.[53][56] Out of the 2,938 Jewish community in the city 1,227 were able to escape from the Nazis before the outbreak of war.[57] Nazi secret police had been observing Polish minority communities in the city since 1936, compiling information, which in 1939 served to prepare lists of Poles to be captured in Operation Tannenberg. On the first day of the war, approximately 1,500 ethnic Poles were arrested, some because of their participation in social and economic life, others because they were activists and members of various Polish organisations. On 2 September 1939, 150 of them were deported to the Sicherheitsdienst camp Stutthof some 30 miles (48 km) from Danzig, and murdered.[58] Many Poles living in Danzig were deported to Stutthof or executed in the Piaśnica forest.

In 1941, Hitler ordered the invasion of the Soviet Union, eventually causing the fortunes of war to turn against Germany. As the Soviet Army advanced in 1944, German populations in Central and Eastern Europe took flight, resulting in the beginning of a great population shift. After the final Soviet offensives began in January 1945, hundreds of thousands of German refugees converged on Danzig, many of whom had fled on foot from East Prussia, some tried to escape through the city's port in a large-scale evacuation involving hundreds of German cargo and passenger ships. Some of the ships were sunk by the Soviets, including the Wilhelm Gustloff after an evacuation was attempted at neighbouring Gdynia. In the process, tens of thousands of refugees were killed.

The city also endured heavy Allied and Soviet air raids. Those who survived and could not escape had to face the Soviet Army, which captured the heavily damaged city on 30 March 1945,[59] followed by large-scale rape[60] and looting.[61][62] In line with the decisions made by the Allies at the Yalta and Potsdam conferences, the city was annexed by Poland. The remaining German residents of the city who had survived the war fled or were forcibly expelled to postwar Germany, and the city was repopulated by ethnic Poles; up to 18 percent (1948) of them had been deported by the Soviets in two major waves from Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union, i.e. from the eastern portion of pre-war Poland.[63]

Contemporary times

Parts of the historic old city of Gdańsk, which had suffered large-scale destruction during the war, were rebuilt during the 1950s and 1960s. The reconstruction was not tied to the city's pre-war appearance, but instead was politically motivated as a means of culturally cleansing and destroying all traces of German influence from the city.[65][66][67] Any traces of German tradition were ignored, suppressed, or regarded as "Prussian barbarism" only worthy of demolition,[68][69] while Flemish/Dutch, Italian and French influences were used to replace the historically accurate Germanic architecture which the city was built upon since the 14th century.[70]

Boosted by heavy investment in the development of its port and three major shipyards for Soviet ambitions in the Baltic region, Gdańsk became the major shipping and industrial center of the Communist People's Republic of Poland.

In December 1970, Gdańsk was the scene of anti-regime demonstrations, which led to the downfall of Poland's communist leader Władysław Gomułka. During the demonstrations in Gdańsk and Gdynia, military as well as the police opened fire on the demonstrators causing several dozen deaths. Ten years later, in August, 1980, Gdańsk Shipyard was the birthplace of the Solidarity trade union movement, whose opposition to the Communist regime led to the end of Communist Party rule in 1989, and sparked a series of protests that successfully overturned the Communist regimes of the former Soviet bloc. Solidarity's leader, Lech Wałęsa, became President of Poland in 1990. In 2014 the European Solidarity Centre, a museum and library devoted to the history of the movement, opened in Gdańsk.[71]

Gdańsk native Donald Tusk became Prime Minister of Poland in 2007, and President of the European Council in 2014.[72] Today Gdańsk is a major shipping port and tourist destination.

Geography

Climate

Gdańsk has a climate with both oceanic and continental influences. According to some categorizations, it has an oceanic climate (Cfb)[73], while others classify it as belonging to the continental climate zone (Dfb)[74]. It actually depends on whether the mean reference temperature for the coldest winter month is set at −3 °C (27 °F) or 0 °C (32 °F). Gdańsk's dry winters and the precipitation maximum in summer are indicators of continentality. However seasonal extremes are less pronounced than those in inland Poland.

The city has moderately cold and cloudy winters with mean temperature in January and February near or below 0 °C (32 °F) and mild summers with frequent showers and thunderstorms. Average temperatures range from −1.0 to 17.2 °C (30 to 63 °F) and average monthly rainfall varies 17.9 to 66.7 millimetres (1 to 3 in) per month with a rather low annual total of 507.3 millimetres (20 in). In general, it is damp, variable, and mild.

The seasons are clearly differentiated. Spring starts in March and is initially cold and windy, later becoming pleasantly warm and often very sunny. Summer, which begins in June, is predominantly warm but hot at times with temperature reaching as high as 30 to 35 °C (86 to 95 °F) at least once per year with plenty of sunshine interspersed with heavy rain. Gdańsk averages 1,700 hours of sunshine per year. July and August are the warmest months. Autumn comes in September and is at first warm and usually sunny, turning cold, damp, and foggy in November. Winter lasts from December to March and includes periods of snow. January and February are the coldest months with the temperature sometimes dropping as low as −15 °C (5 °F).

| Climate data for Gdańsk (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.3 (70.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

2.9 (37.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.0 (30.2) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

2.5 (36.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.0 (59) |

17.2 (63) |

17.2 (63) |

13.3 (55.9) |

8.9 (48) |

3.8 (38.8) |

0.7 (33.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.4 (25.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

2.7 (36.9) |

7.4 (45.3) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

5.8 (42.4) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

4.7 (40.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 24.6 (0.969) |

17.9 (0.705) |

22.4 (0.882) |

29.5 (1.161) |

48.9 (1.925) |

63.5 (2.5) |

66.7 (2.626) |

55.8 (2.197) |

54.9 (2.161) |

47.4 (1.866) |

42.0 (1.654) |

33.7 (1.327) |

507.3 (19.972) |

| Average precipitation days | 15 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 162 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 39 | 70 | 134 | 163 | 244 | 259 | 236 | 225 | 174 | 105 | 45 | 32 | 1,726 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization[75] | |||||||||||||

Economy

The industrial sections of the city are dominated by shipbuilding, petrochemical & chemical industries, and food processing. The share of high-tech sectors such as electronics, telecommunications, IT engineering, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals is on the rise. Amber processing is also an important part of the local economy, as the majority of the world's amber deposits lie along the Baltic coast. The Pomeranian Voivodeship, including Gdańsk, is also a major tourist destination in the summer, as millions of Poles and other European tourists flock to the beaches of the Baltic coastline. Major companies in Gdańsk:

- Acxiom – IT

- Arla Foods – food processing

- Bayer Shared Service Centre – finance & accounting

- Cognor – steel, engineering, capital goods

- Coleman Research – knowledge broker

- Crist – shipbuilding

- Delphi – automotive parts

- Dr. Oetker – food processing

- Grupa Lotos – energy, petrol refinery

- Energa Trading – electrical and heat energy

- Bank BPH – finance

- Gdańska Stocznia Remontowa – shipbuilding

- Elektrociepłownie Wybrzeże – energy

- LPP – retail

- Polnord Energobudowa – construction company

- Petrobaltic – energy, oil drilling

- Intel – IT

- IBM – IT

- IVONA – IT

- FINEOS – IT FINEOS Locations

- Wirtualna Polska – internet service

- Kainos – IT

- Lufthansa Systems – IT

- Jeppesen – IT

- Compuware – IT

- Thomson Reuters – media

- ThyssenKrupp – steel, engineering, capital goods

- Maersk Line – services & pick-up

- Transcom WorldWide – business processing outsourcing

- Jysk – retail

- Meritum Bank – finance

- Glencore – raw materials

- Orlen Morena – energy

- Fosfory Ciech – chemical company

- Hydrobudowa – construction company

- Llentabhallen – steel constructions

- Ziaja – cosmetics and beauty company

- Stabilator – construction company

- Skanska – construction company

- Flügger – paints manufacturing

- HD heavy duty – retail

- Dresser Wayne – retail fueling systems

- First Data – finance

- Masterlease – finance

- Transcom WorldWide – business processing outsourcing

- Weyerhaeuser Cellulose Fibres – cellulose fibre manufacturing

- Gdańsk Shipyard – shipbuilding

- OIE Support – education services (part of Laureate International Universities)

- PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP – professional services

- Kemira – chemical industry group

- BreakThru Films – animated film studio

- Schibsted – IT

- Regus – business support services

- Mango Media – home shopping channel

- MOL Europe – shipping

- VB Leasing – finance

- Metsä Group – forest industry

- Competence Call Centre – call centre

- EPAM Systems – IT

- Esotiq&Henderson – retail

- Bayer – chemical and pharmaceutical company

- Playsoft – IT

- Staples Advantage – office products

- Deloitte – professional services

- KPMG – professional services

- Comarch – IT

- ESO Audit – professional services

- TF Bank – finance

Main sights

Architecture

The city has some buildings surviving from the time of the Hanseatic League. Most tourist attractions are located along or near Ulica Długa (Long Street) and Długi Targ (Long Market), a pedestrian thoroughfare surrounded by buildings reconstructed in historical (primarily during the 17th century) style and flanked at both ends by elaborate city gates. This part of the city is sometimes referred to as the Royal Route, since it was once the former path of processions for visiting Kings of Poland.

Walking from end to end, sites encountered on or near the Royal Route include:

- Highland Gate (Brama Wyżynna)

- Torture House (Katownia)

- Prison Tower (Wieża więzienna)

- Mansion of the Society of Saint George (Dwór Bractwa św. Jerzego)

- Golden Gate (Złota Brama)

- Long Street (Ulica Długa)

- Uphagen's House (Dom Uphagena)

- Lion's Castle (Lwi Zamek)

- Main Town Hall (Ratusz Głównego Miasta)

- Long Market (Długi Targ)

- Artus' Court (Dwór Artusa)

- Neptune's Fountain (Fontanna Neptuna)

- Golden House (Złota Kamienica)

- Green Gate (Zielona Brama)

Gdańsk has a number of historical churches:

- St. Bridget

- St. Catherine

- St. John

- St. Mary (Bazylika Mariacka), a municipal church built during the 15th century, is the largest brick church in the world.

- St. Nicholas

- St. James

- St. Joseph

- St. Peter and Paul

- St. Barbara

- Corpus Christi

The city's 17th-century fortifications represent one of Poland's official national Historic Monuments (Pomnik historii), as designated on 16 September 1994 and tracked by the National Heritage Board of Poland.

Other main sights in the historical city centre include:

- Royal Chapel of the Polish King John III Sobieski

- Żuraw – medieval port crane

- Gradowa Hill

- Granaries on the Ołowianka and Granary Islands

- Great Armoury

- John III Sobieski Monument

- Old Town Hall

- Jan Heweliusz Monument

- Great Mill

- Small Mill

- House of Research Society

- Polish Post Office, site of the 1939 battle

- brick gothic town gates, i.e. Mariacka Gate, Straganiarska Gate, Cow Gate

Main sights outside the historical city centre include:

- Abbot's Palace in the Oliwa Park

- Lighthouse in Nowy Port

- Oliwa Cathedral

- Pachołek Hill – an observation point in Oliwa

- Pier in Brzeźno

- Westerplatte

- Wisłoujście Fortress

- Gdańsk Zoo

Museums

- National Museum (Muzeum Narodowe)

- Department of Ancient Art - contains a number of important artworks, including Hans Memling's Last Judgement

- Green Gate

- Department of Modern Art - in the Abbot's Palace in Oliwa

- Ethnography Department - in the Abbot's Granary in Oliwa

- Gdańsk Photography Gallery

- Historical Museum (Muzeum Historyczne Miasta Gdańska):

- Main Town Hall

- Artus' Court

- Uphagen's House

- Amber Museum (Muzeum Bursztynu)

- Museum of the Polish Post (Muzeum Poczty Polskiej)

- Wartownia nr 1 na Westerplatte

- Museum of Tower Clocks (Muzeum Zegarów Wieżowych)

- Wisłoujście Fortress

- National Maritime Museum, Gdańsk (Narodowe Muzeum Morskie):

- Żuraw Crane

- Granaries in Ołowianka

- museum ship SS Soldek is anchored on the Motława River and was the first ship built in post-war Poland.

- Archeological Museum (Muzeum Archeologiczne)

- Gdańsk Nowy Port Lighthouse (Latarnia Morska Gdańsk Nowy Port)

- Izba Pamięci Wincentego Pola w Gdańsku-Sobieszewie

- Archdiocese Museum (Muzeum Archidiecezjalne)

- Museum of the Second World War

Entertainment

- Polish Baltic Philharmonic

- Baltic Opera

- Teatr Wybrzeże

- Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre is a Shakespearean theatre built on the historical site of a 17th-century playhouse where English travelling players came to perform. The new theatre, completed in 2014, hosts the annual Gdańsk Shakespeare Festival.[79]

Transport

.jpg)

- Gdańsk Lech Wałęsa Airport – an international airport located in Gdańsk;

- The Szybka Kolej Miejska, (SKM) the Fast Urban Railway, functions as a Metro system for the Tricity area including Gdańsk, Sopot and Gdynia, operating frequent trains to 27 stations covering the Tricity.[80] The service is operated by electric multiple unit trains at a frequency of 6 minutes to 30 minutes between trains (depending on the time of day) on the central section between Gdańsk and Gdynia, and less frequently on outlying sections. The SKM system has been extended northwest of the Tricity, to Wejherowo, Lębork and Słupsk, 110 kilometres (68 miles) west of Gdynia, and to the south it has been extended to Tczew, 31 kilometres (19 miles) south of Gdańsk.

- Railways: The principal station in Gdańsk is Gdańsk Główny railway station, served by both SKM local trains and PKP long distance trains. In addition, long distance trains also stop at Gdańsk Oliwa railway station, Gdańsk Wrzeszcz railway station, Sopot and Gdynia. Gdańsk also has nine (9) other railway stations, served by local SKM trains;

- Long distance trains are operated by PKP Intercity which provides connections with all major Polish cities, including Warsaw, Kraków, Łódź, Poznań, Katowice and Szczecin, and with the neighbouring Kashubian Lakes region.

In 2011–2015 the Warsaw-Gdańsk-Gdynia railway route underwent a major upgrading costing $3 billion, partly funded by the European Investment Bank, including track replacement, realignment of curves and relocation of sections of track to allow speeds up to 200 km/h (124 mph), modernization of stations, and installation of the most modern ETCS signalling system, which was completed in June 2015. In December 2014 new Alstom Pendolino high-speed trains were put into service between Gdańsk, Warsaw and Kraków reducing the rail travel time from Gdańsk to Warsaw to 2 hours 58 minutes,[81][82] further reduced in December 2015 to 2 hours 39 minutes.[83]

- A new railway, Pomorska Kolej Metropolitalna (PKM, the 'Pomeranian Metropolitan Railway'), commenced service on 1 September 2015, connecting Gdańsk Lech Wałęsa Airport with Wrzeszcz and downtown Gdańsk. It connects to the Szybka Kolej Miejska (Tricity) (SKM) which provides further connections to the entire area served by SKM.

- City buses and trams are operated by ZTM Gdańsk (Zarząd Transportu Miejskiego w Gdańsku).

- Port of Gdańsk – a seaport located on the southern coast of Gdańsk Bay within the city;

- Obwodnica Trojmiejska – part of expressway S6 that bypasses the cities of Gdańsk, Sopot and Gdynia.

- The A1 motorway connects the port and city of Gdańsk with the southern border of the country. As of 2014, some fragments of the A1 motorway are still incomplete.

Gdańsk is the starting point of the EuroVelo 9 cycling route which continues southward through Poland, then into the Czech Republic, Austria and Slovenia before ending at the Adriatic Sea in Pula, Croatia.

_2010-07-12_016.jpg) Gdańsk main railway station (built 1896–1900)

Gdańsk main railway station (built 1896–1900) Fast Urban Rail train

Fast Urban Rail train Gdańsk tram – Pesa Jazz Duo

Gdańsk tram – Pesa Jazz Duo- Gdańsk bus - Solaris Urbino 12

- S6 expressway Tricity

Sports

There are many popular professional sports teams in the Gdańsk and Tricity area. Amateur sports are played by thousands of Gdańsk citizens and also in schools of all levels (elementary, secondary, university).

The city's professional football club is Lechia Gdańsk. Founded in 1945, they play in the Ekstraklasa, Poland's top division. Their home stadium, Stadion Energa Gdańsk, was one of the four Polish stadiums to host the UEFA Euro 2012 competition. Other notable clubs include rugby club Lechia Gdańsk (12 times Polish Champion) and motorcycle speedway club Wybrzeże Gdańsk.

The city's Hala Olivia was a venue for the official 2009 EuroBasket.[84]

Politics and local government

Contemporary Gdańsk is the capital of the province called Pomeranian Voivodeship and is one of the major centers of economic and administrative life in Poland. Many important agencies of the state and local government levels have their main offices here: the Provincial Administration Office, the Provincial Government, the Ministerial Agency of the State Treasury, the Agency for Consumer and Competition Protection, the National Insurance regional office, the Court of Appeals, and the High Administrative Court.

Regional centre

Gdańsk Voivodeship was extended in 1999 to include most of former Słupsk Voivodeship, the western part of Elbląg Voivodeship and Chojnice County from Bydgoszcz Voivodeship to form the new Pomeranian Voivodeship. The area of the region was thus extended from 7,394 to 18,293 square kilometres (2,855 to 7,063 sq mi) and the population rose from 1,333,800 (1980) to 2,198,000 (2000). By 1998, Tricity constituted an absolute majority of the population; almost half of the inhabitants of the new region live in the centre.

Municipal government

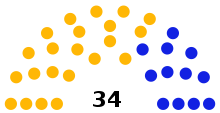

Legislative power in Gdańsk is vested in a unicameral Gdańsk City Council (Rada Miasta), which comprises 34 members. Council members are elected directly every four years. Like most legislative bodies, the City Council divides itself into committees which have the oversight of various functions of the city government.

- City Council in 2002–2006[85]

- Platforma Obywatelska – 15 seats

- Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej-Unia Pracy – 6 seats

- KW Wyborców i Sympatyków Lecha Kaczyńskiego Prawo i Samorządność – 6 seats

- Liga Polskich Rodzin – 5 seats

- Samoobrona – 1 seat

- Obywatelski Komitet Bogdana Borusewicza – 1 seat

- City Council in 2006–2010[86]

- Platforma Obywatelska – 21 seats

- Prawo i Sprawiedliwość – 13 seats

- City Council in 2010–2014[87]

- Platforma Obywatelska – 26 seats

- Prawo i Sprawiedliwość – 7 seats

- Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej – 1 seat

- City Council in 2014–2018[88]

- Platforma Obywatelska – 22 seats

- Prawo i Sprawiedliwość – 12 seats

Districts

Gdańsk is divided into 34 administrative divisions: 6 dzielnicas and 28 osiedles. Gdańsk dzielnicas include: Chełm, Piecki-Migowo, Przymorze Wielkie, Śródmieście, Wrzeszcz Dolny, Wrzeszcz Górny.

Osiedles: Aniołki, Brętowo, Brzeźno, Jasień, Kokoszki, Krakowiec-Górki Zachodnie, Letnica, Matarnia, Młyniska, Nowy Port, Oliwa, Olszynka, Orunia-Św. Wojciech-Lipce, Osowa, Przeróbka, Przymorze Małe, Rudniki, Siedlce, Sobieszewo Island, Stogi, Strzyża, Suchanino, Ujeścisko-Łostowice, VII Dwór, Wzgórze Mickiewicza, Zaspa-Młyniec, Zaspa-Rozstaje, Żabianka-Wejhera-Jelitkowo-Tysiąclecia.

Education and science

There are 15 higher schools including 3 universities. In 2001 there were 60,436 students, including 10,439 graduates.

- Gdańsk University (Uniwersytet Gdański)

- Gdańsk University of Technology (Politechnika Gdańska)

- Gdańsk Medical University (Gdański Uniwersytet Medyczny)

- Academy of Physical Education and Sport of Gdańsk (Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego i Sportu im. Jędrzeja Śniadeckiego)

- Musical Academy (Akademia Muzyczna im. Stanisława Moniuszki)

- Arts Academy (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych)[89]

- Institute of Fluid Flow Machinery of the Polish Academy of Sciences - Instytut Maszyn Przepływowych im. Roberta Szewalskiego PAN[90]

- Instytut Budownictwa Wodnego PAN

- Ateneum – Szkoła Wyższa

- Gdańska Wyższa Szkoła Humanistyczna

- Gdańska Wyższa Szkoła Administracji

- Wyższa Szkoła Społeczno-Ekonomiczna

- Wyższa Szkoła Turystyki i Hotelarstwa w Gdańsku

- Wyższa Szkoła Zarządzania

- WSB Universities – WSB University in Gdańsk[91]

Scientific and regional organizations

- Gdańsk Scientific Society

- Baltic Institute (Instytut Bałtycki), established 1925 in Toruń, since 1946 (?) in Gdańsk

- TNOiK – Towarzystwo Naukowe Organizacji i Kierowania (Scientific Society for Organization and Management) O/Gdańsk

- IBNGR – Instytut Badań nad Gospodarką Rynkową (The Gdańsk Institute for Market Economics)[92]

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

Gdańsk is twinned with:[93][in chronological order]

Partnerships and cooperation

Gallery

Gdańsk Hilton Hotel

Gdańsk Hilton Hotel

- Długi Targ Street, Old Town

Mariacka Street

Mariacka Street.jpg) Długa Street

Długa Street- Lion's Castle Tenement House

- John III Sobieski Monument in Gdańsk

- Gdańsk – Neptune's Fountain

- Gdańsk – Townhouses

Westerplatte – Monument nearby Gdańsk

Westerplatte – Monument nearby Gdańsk_ID_635538.jpg) Old Town Hall

Old Town Hall Great Mill (left) and Millers' Guild House (right)

Great Mill (left) and Millers' Guild House (right)

Church of St. John

Church of St. John- Rybackie Pobrzeże

Millers' Guild House

Millers' Guild House_ID_635439.jpg) Saint Barbara church

Saint Barbara church Swan Tower

Swan Tower- Gaol Tower

- Gdańsk Library of Polish Academy of Sciences

Jan Heweliusz Monument

Jan Heweliusz Monument Port of Gdańsk from mainmast of Fryderyk Chopin

Port of Gdańsk from mainmast of Fryderyk Chopin Gdańsk University – Faculty of Law and Administration

Gdańsk University – Faculty of Law and Administration Modern blocks in Obrońców Wybrzeża Street

Modern blocks in Obrońców Wybrzeża Street

Population

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1939 | 250,000 | — |

| 1946 | 117,894 | −52.8% |

| 1950 | 194,633 | +65.1% |

| 1960 | 286,940 | +47.4% |

| 1970 | 365,600 | +27.4% |

| 1980 | 456,707 | +24.9% |

| 1987 | 469,053 | +2.7% |

| 1990 | 465,143 | −0.8% |

| 1995 | 463,019 | −0.5% |

| 2000 | 462,995 | −0.0% |

| 2005 | 458,093 | −1.1% |

| 2010 | 460,509 | +0.5% |

| 2012 | 460,427 | −0.0% |

| 2014 | 461,489 | +0.2% |

| 2017 | 464,254 | +0.6% |

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "the definition of gdansk". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ "Poland – largest cities (per geographical entity)". World Gazetteer. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ "Millions at Gdansk's St. Dominic's Fair". www.pap.pl. Article copied to polska.pl. 2016-08-21. Retrieved 2016-12-30.

- ↑ From the history of Gdańsk city name, as explained at Gdańsk Guide

- 1 2 Tighe, Carl (1990). Gdańsk: national identity in the Polish-German borderlands. Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745303468. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ Gumowski, Marian (1966). Handbuch der polnischen Siegelkunde (in German). Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ Also in 1454, 1468, 1484, and 1590

- ↑ Also in 1399, 1410, and 1414–1438

- ↑ Also in 1410, 1414

- ↑ Gdańsk, in: Kazimierz Rymut, Nazwy Miast Polski, Ossolineum, Wrocław 1987

- ↑ Hubert Gurnowicz, Gdańsk, in: Nazwy miast Pomorza Gdańskiego, Ossolineum, Wrocław 1978

- ↑ Baedeker's Northern Germany, Karl Baedeker Publishing, Leipzig 1904

- 1 2 Loew, Peter Oliver: Danzig. Biographie einer Stadt, Munich 2011, p. 24.

- 1 2 Wazny, Tomasz; Paner, Henryk; Golebiewski, Andrzej; Koscinski, Bogdan: Early medieval Gdansk/Danzig revisited (EuroDendro 2004), Rendsburg 2004, pdf-abstract Archived September 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Loew (2011), p. 24; Wazny et al. (2004), abstract Archived September 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Hess, Corina (2007). Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit. Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 39. ISBN 3-8258-8711-1.

- ↑ admin2. "1000 LAT GDAŃSKA W ŚWIETLE WYKOPALISK". Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- 1 2 Hess, Corina (2007). Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit. Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 40. ISBN 3-8258-8711-1.

- 1 2 name="harlander">Harlander, Christa (2004). Stadtanlage und Befestigung von Danzig (zur Zeit des Deutschen Ordens). GRIN Verlag. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-638-75010-3.

- ↑ Zbierski, Andrzej (1978). Struktura zawodowa, spoleczna i etnicza ludnosci. In Historia Gdanska, Vol. 1. Wydawnictwo Morskie. pp. 228–9. ISBN 83-86557-00-1.

- ↑ Turnock, David (1988). The Making of Eastern Europe: From the Earliest Times to 1815. Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 0-415-01267-8.

- ↑ name="lingenberg">Lingenberg, Heinz (1982). Die Anfänge des Klosters Oliva und die Entstehung der deutschen Stadt Danzig: die frühe Geschichte der beiden Gemeinwesen bis 1308/10. Klett-Cotta. p. 292. ISBN 978-3-129-14900-3.

- ↑ ‘The Slippery Memory of Men’: The Place of Pomerania in the Medieval Kingdom of Poland by Paul Milliman page 73, 2013

- 1 2 Hess, Corina (2007). Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit. Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. pp. 40–41. ISBN 3-8258-8711-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Hess, Corina (2007). Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit. Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 41. ISBN 3-8258-8711-1.

- 1 2 3 Hartmut Boockmann, Ostpreussen und Westpreussen, Siedler, 2002, p.158, ISBN 3-88680-212-4

- 1 2 James Minahan, One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, ISBN 0-313-30984-1, p.376 Google Books

- ↑ Thomas Urban: "Rezydencja książąt Pomorskich". (in Polish) Archived August 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hess, Corina (2007). Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit. Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. pp. 41–42. ISBN 3-8258-8711-1.

- ↑ Frankot, Edda (2012). 'Of Laws of Ships and Shipmen': Medieval Maritime Law and its Practice in Urban Northern Europe. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-7486-4624-1.

- 1 2 Hess, Corina (2007). Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit. Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 42. ISBN 3-8258-8711-1.

- ↑ Loew, Peter O. (2011). Danzig: Biographie einer Stadt. München: C.H.Beck. p. 43. ISBN 978-3-406-60587-1.

- ↑ Sobecki, Sebastian (2016). "Danzig". Europe: A Literary History, 1348–1418, ed. David Wallace. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 635–41.

- ↑ "II Pokój Toruński i przyłączenie Gdańska do Rzeczpospolitej". mgdansk.pl.

- ↑ Cahoon, Ben. "Poland". worldstatesmen.org.

- ↑ Danzig – Gdańsk until 1920

- 1 2 3 Hess, Corina (2007). Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit. Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 45. ISBN 3-8258-8711-1.

- ↑ Hess, Corina (2007). Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit. Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 45. ISBN 3-8258-8711-1. : "Geben wir und verlehen unnsir Stadt Danczk das sie zcu ewigen geczeiten nymands for eynem herrn halden noc gehorsam zcu weszen seyn sullen in weltlichen sachen."

- ↑ Juliette Roding, Lex Heerma van Voss (1996). The North Sea and culture (1550–1800): proceedings of the international conference held at Leiden 21–22 April 1995. Uitgeverij Verloren. p. 103. ISBN 90-6550-527-X.

- ↑ "Zielona Brama w Gdańsku". wilanowmiasta.gazeta.pl (in Polish). 2007-02-18. Archived from the original on 2007-12-29. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ↑ Bömelburg, Hans-Jürgen, Zwischen polnischer Ständegesellschaft und preußischem Obrigkeitsstaat: vom Königlichen Preußen zu Westpreußen (1756–1806), München: Oldenbourg, 1995, (Schriften des Bundesinstituts für Ostdeutsche Kultur und Geschichte (Oldenburg); 5), zugl.: Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg-Univ., Diss., 1993, 549 pp.

- ↑ Historia Polski 1795–1815 Andrzej Chwalba Kraków 2000, page 441

- 1 2 Planet, Lonely. "History of Gdańsk – Lonely Planet Travel Information". lonelyplanet.com.

- ↑ Dzieje Gdańska Edmund Cieślak, Czesław Biernat Wydawn. Morskie, 1969 page 370

- ↑ Dzieje Polski w datach Jerzy Borowiec, Halina Niemiec page 161

- ↑ Polska, losy państwa i narodu Henryk Samsonowicz 1992 Iskry page 282

- ↑ In the 1923 census 7,896 people out of 335,921 gave Polish, Kashubian or Masurian as their native language. Ergebnisse der Volks- und Berufszählung vom 1. November 1923 in der Freien Stadt Danzig (in German). Verlag des Statistischen Landesamtes der Freien Stadt Danzig. 1926. . Polish estimates of the Polish minority during the interwar era, however, range from 37,000 to 100,000 (9%–34%). Studia historica Slavo-Germanica, Tomy 18–20page 220 Uniwersytet Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu. Instytut Historii Wydawnictwo Naukowe imienia. Adama Mickiewicza, 1994.

- ↑ The history of the German resistance, 1933–1945 Peter Hoffmann page 37 McGill-Queen's University Press 1996

- ↑ Hitler Joachim C. Fest page 586 Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2002

- ↑ Blitzkrieg w Polsce wrzesien 1939 Richard Hargreaves page 84 Bellona, 2009

- ↑ A military history of Germany, from the eighteenth century to the present dayMartin Kitchen page 305 Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1975

- ↑ International history of the twentieth century and beyond Antony Best page 181 Routledge; 2 edition (July 30, 2008)

- 1 2 "Gdansk". Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ↑ Bauer, Yehuda (1981). American Jewry and the Holocaust. Wayne State University Press. p. 145. ISBN 0-8143-1672-7. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ "Die „Lösung der Judenfrage" in der Freien Stadt Danzig". www.shoa.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2011-06-29.

- ↑ "Gdansk, Poland". jewishgen.org.

- ↑ Żydzi na terenie Wolnego Miasta Gdańska w latach 1920–1945:działalność kulturalna, polityczna i socjalnaGrzegorz Berendt Gdańskie Tow. Nauk., Wydz. I Nauk Społecznych i Humanistycznych, 1997 page 245

- ↑ Museums Stutthof in Sztutowo. Retrieved January 31, 2007. Archived August 24, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Gdańsk.pl". 3 March 2006. Archived from the original on 3 March 2006.

- ↑ Grzegorz Baziur, OBEP IPN Kraków (2002). "Armia Czerwona na Pomorzu Gdańskim 1945–1947 (Red Army in Gdańsk Pomerania 1945–1947)". Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej (Institute of National Remembrance Bulletin). 7: 35–38.

- ↑ Biskupski, Mieczysław B. The History of Poland. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, p. 97.

- ↑ Tighe, Carl. Gdańsk: National Identity in the Polish-German Borderlands. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 199.

- ↑ Loew, Peter Oliver (2011). Danzig – Biographie einer Stadt (in German). C.H. Beck. p. 232. ISBN 978-3-406-60587-1. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ Lech Krzyżanowski; Michał Wożniak; Marek Źak; Wacław Górski (1995). Beautiful historic Gdańsk. Excalibur. p. 769.

- ↑ Kozinska, Bogdana; Bingen, Dieter (2005). Die Schleifung – Zerstörung und Wiederaufbau historischer Bauten in Deutschland und Polen (in German). Deutsches Polen-Institut. p. 67. ISBN 3-447-05096-9. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ Loew, Peter Oliver (2011). Danzig – Biographie einer Stadt (in German). C.H. Beck. p. 146. ISBN 978-3-406-60587-1.

- ↑ Kalinowski, Konstanty; Bingen, Dieter (2005). Die Schleifung – Zerstörung und Wiederaufbau historischer Bauten in Deutschland und Polen (in German). Deutsches Polen-Institut. p. 89. ISBN 3-447-05096-9. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- ↑ Friedrich, Jacek (2010). Neue Stadt in altem Glanz – Der Wiederaufbau Danzigs 1945–1960 (in German). Böhlau. pp. 30, 40. ISBN 3-412-20312-2.

- ↑ Czepczynski, Mariusz (2008). Cultural landscapes of post-socialist cities: representation of powers and needs. Ashgate publ. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-7546-7022-3.

- ↑ Friedrich, Jacek (2010). Neue Stadt in altem Glanz – Der Wiederaufbau Danzigs 1945–1960 (in German). Böhlau. pp. 34, 102. ISBN 3-412-20312-2.

- ↑ "W Gdańsku otwarto Europejskie Centrum Solidarności" (in Polish). Onet.pl. 31 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ↑ "Italy's Mogherini and Poland's Tusk get top EU jobs". BBC. 30 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ↑ "Gdansk". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ↑ "Köppen climate classification". Britannica. Retrieved 14 February 2018

- ↑ "World Weather Information Service – Gdańsk". WMO. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ Russell Sturgis; Arthur Lincoln Frothingham (1915). A history of architecture. Baker & Taylor. p. 293.

- ↑ Paul Wagret; Helga S. B. Harrison (1964). Poland. Nagel. p. 302.

- ↑ ROBiDZ w Gdańsku. "Kaplica Królewska w Gdańsku". www.wrotapomorza.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on February 10, 2015. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ↑ Snow, Georgia (3 September 2014). "Elizabethan playhouse in Poland to host work by Shakespeare's Globe". The Stage. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ↑ SKM Passenger Information, Map http://www.skm.pkp.pl/

- ↑ Polish Pendolino launches 200 km/h operation, Railway Gazette International, 15 December 2014

- ↑ "Pendolino z Trójmiasta do Warszawy. Więcej pytań niż odpowiedzi". trojmiasto.pl.

- ↑ ';Jeszcze szybciej z Warszawy do Gdańska,' Kurier Kolejowy 9 01 2015 http://www.kurierkolejowy.eu/aktualnosci/22716/Jeszcze-szybciej-z-Warszawy-do-Gdanska.html

- ↑ 2009 EuroBasket, ARCHIVE.FIBA.com, Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ "Państwowa Komisja Wyborcza: Wybory samorządowe". wybory2002.pkw.gov.pl. Retrieved 2015-10-09.

- ↑ "Geografia wyborcza – Wybory samorządowe – Państwowa Komisja Wyborcza". wybory2006.pkw.gov.pl. Retrieved 2015-10-09.

- ↑ "Wybory Samorządowe 2010 – Geografia wyborcza – Województwo pomorskie – – m. Gdańsk". wybory2010.pkw.gov.pl. Retrieved 2015-10-09.

- ↑ "Państwowa Komisja Wyborcza | Gdańsk". wybory2014.pkw.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 2014-12-18. Retrieved 2015-10-09.

- ↑ "Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Gdańsku". asp.gda.pl.

- ↑ "Institute of Fluid Flow Machinery of the Polish Academy of Sciences". imp.gda.pl/en.

- ↑ WSB University in Gdańsk Archived 2016-02-14 at the Wayback Machine. – WSB Universities

- ↑ "The Gdańsk Institute for Market Economics". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2008-02-09. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 "Partner Cities" (in Polish and English). City of Gdańsk. 27 May 2008. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ↑ Frohmader, Andrea. "Bremen – Referat 32 Städtepartnerschaften / Internationale Beziehungen" [Bremen – Unit 32 Twinning / International Relations]. Das Rathaus Bremen Senatskanzlei [Bremen City Hall – Senate Chancellery] (in German). Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ↑ "Sister Cities International (SCI)". Sister-cities.org. Archived from the original on 2015-06-13. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- ↑ "Saint Petersburg in figures – International and Interregional Ties". Saint Petersburg City Government. Archived from the original on 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ↑ "Villes jumelées avec la Ville de Nice" (in French). Ville de Nice. Archived from the original on October 29, 2012. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- ↑ "Le Havre – Les villes jumelées" [Le Havre – Twin towns]. City of Le Havre (in French). Archived from the original on 2013-07-29. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

Bibliography

- Kimmich, Christoph M, (1968). The free city: Danzig and German foreign policy, 1919–1934. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- Rudziński, Grzegorz (1 March 2001). Gdańsk. Bonechi. ISBN 978-88-476-0517-6. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- Simson, Paul (October 2009). Geschichte Der Stadt Danzig. BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 978-1-115-53256-3. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gdańsk. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Danzig. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Gdańsk. |

| Look up Gdańsk in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Official website

- Extensive Danzig, East & West Prussian Historical Materials (in English) & (in German)

- Regional Tourist Board website

- Local Tourist Board website

- (in Polish) Virtual Gdańsk (portal)

- (in German) Danzig(portal)

- Mariacka Street Panoramic Photo

- Visit Gdanks

- 7 Reasons to Fall in Love with Gdańsk

.jpg)