Dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles[note 1] of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago, although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is the subject of active research. They became the dominant terrestrial vertebrates after the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event 201.3 million years ago; their dominance continued through the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. The fossil record demonstrates that birds are modern feathered dinosaurs, having evolved from earlier theropods during the Late Jurassic epoch. As such, birds were the only dinosaur lineage to survive the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event approximately 66 million years ago. Dinosaurs can therefore be divided into avian dinosaurs, or birds; and non-avian dinosaurs, which are all dinosaurs other than birds.

| Dinosaurs | |

|---|---|

| |

| A collection of fossil dinosaur skeletons. Clockwise from top left: Microraptor gui (a winged theropod), Apatosaurus louisae (a giant sauropod), Edmontosaurus regalis (a duck-billed ornithopod), Triceratops horridus (a horned ceratopsian), Stegosaurus stenops (a plated stegosaur), Pinacosaurus grangeri (an armored ankylosaur) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dracohors |

| Clade: | Dinosauria Owen, 1842 |

| Major groups | |

| |

Dinosaurs are a varied group of animals from taxonomic, morphological and ecological standpoints. Birds, at over 10,000 living species, are the most diverse group of vertebrates besides perciform fish. Using fossil evidence, paleontologists have identified over 500 distinct genera and more than 1,000 different species of non-avian dinosaurs. Dinosaurs are represented on every continent by both extant species (birds) and fossil remains. Through the first half of the 20th century, before birds were recognized to be dinosaurs, most of the scientific community believed dinosaurs to have been sluggish and cold-blooded. Most research conducted since the 1970s, however, has indicated that all dinosaurs were active animals with elevated metabolisms and numerous adaptations for social interaction. Some were herbivorous, others carnivorous. Evidence suggests that all dinosaurs were egg-laying; and that nest-building was a trait shared by many dinosaurs, both avian and non-avian.

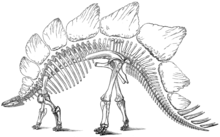

While dinosaurs were ancestrally bipedal, many extinct groups included quadrupedal species, and some were able to shift between these stances. Elaborate display structures such as horns or crests are common to all dinosaur groups, and some extinct groups developed skeletal modifications such as bony armor and spines. While the dinosaurs' modern-day surviving avian lineage (birds) are generally small due to the constraints of flight, many prehistoric dinosaurs (non-avian and avian) were large-bodied—the largest sauropod dinosaurs are estimated to have reached lengths of 39.7 meters (130 feet) and heights of 18 meters (59 feet) and were the largest land animals of all time. Still, the idea that non-avian dinosaurs were uniformly gigantic is a misconception based in part on preservation bias, as large, sturdy bones are more likely to last until they are fossilized. Many dinosaurs were quite small: Xixianykus, for example, was only about 50 cm (20 in) long.

Since the first dinosaur fossils were recognized in the early 19th century, mounted fossil dinosaur skeletons have been major attractions at museums around the world, and dinosaurs have become an enduring part of world culture. The large sizes of some dinosaur groups, as well as their seemingly monstrous and fantastic nature, have ensured dinosaurs' regular appearance in best-selling books and films, such as Jurassic Park. Persistent public enthusiasm for the animals has resulted in significant funding for dinosaur science, and new discoveries are regularly covered by the media.

Etymology

The taxon 'Dinosauria' was formally named in 1842 by paleontologist Sir Richard Owen, who used it to refer to the "distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles" that were then being recognized in England and around the world.[1][2] The term is derived from Ancient Greek δεινός (deinos), meaning 'terrible, potent or fearfully great', and σαῦρος (sauros), meaning 'lizard or reptile'.[1][3] Though the taxonomic name has often been interpreted as a reference to dinosaurs' teeth, claws, and other fearsome characteristics, Owen intended it merely to evoke their size and majesty.[4]

Other prehistoric animals, including pterosaurs, mosasaurs, ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and Dimetrodon, while often popularly conceived of as dinosaurs, are not taxonomically classified as dinosaurs.[5] Pterosaurs are distantly related to dinosaurs, being members of the clade Ornithodira. The other groups mentioned are, like dinosaurs and pterosaurs, members of Sauropsida (the reptile and bird clade), except Dimetrodon (which is a synapsid).

Definition

Under phylogenetic nomenclature, dinosaurs are usually defined as the group consisting of the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of Triceratops and modern birds (Neornithes), and all its descendants.[6] It has also been suggested that Dinosauria be defined with respect to the MRCA of Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, because these were two of the three genera cited by Richard Owen when he recognized the Dinosauria.[7] Both definitions result in the same set of animals being defined as dinosaurs: "Dinosauria = Ornithischia + Saurischia", encompassing ankylosaurians (armored herbivorous quadrupeds), stegosaurians (plated herbivorous quadrupeds), ceratopsians (herbivorous quadrupeds with horns and frills), ornithopods (bipedal or quadrupedal herbivores including "duck-bills"), theropods (mostly bipedal carnivores and birds), and sauropodomorphs (mostly large herbivorous quadrupeds with long necks and tails).[8]

Birds are now recognized as being the sole surviving lineage of theropod dinosaurs. In traditional taxonomy, birds were considered a separate class that had evolved from dinosaurs, a distinct superorder. However, a majority of contemporary paleontologists concerned with dinosaurs reject the traditional style of classification in favor of phylogenetic taxonomy; this approach requires that, for a group to be natural, all descendants of members of the group must be included in the group as well. Birds are thus considered to be dinosaurs and dinosaurs are, therefore, not extinct.[9] Birds are classified as belonging to the subgroup Maniraptora, which are coelurosaurs, which are theropods, which are saurischians, which are dinosaurs.[10]

Research by Matthew G. Baron, David B. Norman, and Paul M. Barrett in 2017 suggested a radical revision of dinosaurian systematics. Phylogenetic analysis by Baron et al. recovered the Ornithischia as being closer to the Theropoda than the Sauropodomorpha, as opposed to the traditional union of theropods with sauropodomorphs. They resurrected the clade Ornithoscelida to refer to the group containing Ornithischia and Theropoda. Dinosauria itself was re-defined as the last common ancestor of Triceratops horridus, Passer domesticus and Diplodocus carnegii, and all of its descendants, to ensure that sauropods and kin remain included as dinosaurs.[11][12]

General description

Using one of the above definitions, dinosaurs can be generally described as archosaurs with hind limbs held erect beneath the body.[13] Many prehistoric animal groups are popularly conceived of as dinosaurs, such as ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, and pelycosaurs (especially Dimetrodon), but are not classified scientifically as dinosaurs, and none had the erect hind limb posture characteristic of true dinosaurs.[14] Dinosaurs were the dominant terrestrial vertebrates of the Mesozoic Era, especially the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Other groups of animals were restricted in size and niches; mammals, for example, rarely exceeded the size of a domestic cat, and were generally rodent-sized carnivores of small prey.[15]

Dinosaurs have always been an extremely varied group of animals; according to a 2006 study, over 500 non-avian dinosaur genera have been identified with certainty so far, and the total number of genera preserved in the fossil record has been estimated at around 1850, nearly 75% of which remain to be discovered.[16] An earlier study predicted that about 3,400 dinosaur genera existed, including many that would not have been preserved in the fossil record.[17] By September 17, 2008, 1,047 different species of dinosaurs had been named.[18]

In 2016, the estimated number of dinosaur species that existed in the Mesozoic was estimated to be 1,543–2,468.[19][20] Some are herbivorous, others carnivorous, including seed-eaters, fish-eaters, insectivores, and omnivores. While dinosaurs were ancestrally bipedal (as are all modern birds), some prehistoric species were quadrupeds, and others, such as Anchisaurus and Iguanodon, could walk just as easily on two or four legs. Cranial modifications like horns and crests are common dinosaurian traits, and some extinct species had bony armor. Although known for large size, many Mesozoic dinosaurs were human-sized or smaller, and modern birds are generally small in size. Dinosaurs today inhabit every continent, and fossils show that they had achieved global distribution by at least the Early Jurassic epoch.[21] Modern birds inhabit most available habitats, from terrestrial to marine, and there is evidence that some non-avian dinosaurs (such as Microraptor) could fly or at least glide, and others, such as spinosaurids, had semiaquatic habits.[22]

Distinguishing anatomical features

While recent discoveries have made it more difficult to present a universally agreed-upon list of dinosaurs' distinguishing features, nearly all dinosaurs discovered so far share certain modifications to the ancestral archosaurian skeleton, or are clear descendants of older dinosaurs showing these modifications. Although some later groups of dinosaurs featured further modified versions of these traits, they are considered typical for Dinosauria; the earliest dinosaurs had them and passed them on to their descendants. Such modifications, originating in the most recent common ancestor of a certain taxonomic group, are called the synapomorphies of such a group.[23]

A detailed assessment of archosaur interrelations by Sterling Nesbitt[24] confirmed or found the following twelve unambiguous synapomorphies, some previously known:

- in the skull, a supratemporal fossa (excavation) is present in front of the supratemporal fenestra, the main opening in the rear skull roof

- epipophyses, obliquely backward-pointing processes on the rear top corners, present in the anterior (front) neck vertebrae behind the atlas and axis, the first two neck vertebrae

- apex of deltopectoral crest (a projection on which the deltopectoral muscles attach) located at or more than 30% down the length of the humerus (upper arm bone)

- radius, a lower arm bone, shorter than 80% of humerus length

- fourth trochanter (projection where the caudofemoralis muscle attaches on the inner rear shaft) on the femur (thigh bone) is a sharp flange

- fourth trochanter asymmetrical, with distal, lower, margin forming a steeper angle to the shaft

- on the astragalus and calcaneum, upper ankle bones, the proximal articular facet, the top connecting surface, for the fibula occupies less than 30% of the transverse width of the element

- exoccipitals (bones at the back of the skull) do not meet along the midline on the floor of the endocranial cavity, the inner space of the braincase

- in the pelvis, the proximal articular surfaces of the ischium with the ilium and the pubis are separated by a large concave surface (on the upper side of the ischium a part of the open hip joint is located between the contacts with the pubic bone and the ilium)

- cnemial crest on the tibia (protruding part of the top surface of the shinbone) arcs anterolaterally (curves to the front and the outer side)

- distinct proximodistally oriented (vertical) ridge present on the posterior face of the distal end of the tibia (the rear surface of the lower end of the shinbone)

- concave articular surface for the fibula of the calcaneum (the top surface of the calcaneum, where it touches the fibula, has a hollow profile)

Nesbitt found a number of further potential synapomorphies and discounted a number of synapomorphies previously suggested. Some of these are also present in silesaurids, which Nesbitt recovered as a sister group to Dinosauria, including a large anterior trochanter, metatarsals II and IV of subequal length, reduced contact between ischium and pubis, the presence of a cnemial crest on the tibia and of an ascending process on the astragalus, and many others.[6]

j: jugal bone, po: postorbital bone, p: parietal bone, sq: squamosal bone, q: quadrate bone, qj: quadratojugal bone

A variety of other skeletal features are shared by dinosaurs. However, because they are either common to other groups of archosaurs or were not present in all early dinosaurs, these features are not considered to be synapomorphies. For example, as diapsids, dinosaurs ancestrally had two pairs of Infratemporal fenestrae (openings in the skull behind the eyes), and as members of the diapsid group Archosauria, had additional openings in the snout and lower jaw.[25] Additionally, several characteristics once thought to be synapomorphies are now known to have appeared before dinosaurs, or were absent in the earliest dinosaurs and independently evolved by different dinosaur groups. These include an elongated scapula, or shoulder blade; a sacrum composed of three or more fused vertebrae (three are found in some other archosaurs, but only two are found in Herrerasaurus);[6] and a perforate acetabulum, or hip socket, with a hole at the center of its inside surface (closed in Saturnalia tupiniquim, for example).[26][27] Another difficulty of determining distinctly dinosaurian features is that early dinosaurs and other archosaurs from the Late Triassic epoch are often poorly known and were similar in many ways; these animals have sometimes been misidentified in the literature.[28]

Dinosaurs stand with their hind limbs erect in a manner similar to most modern mammals, but distinct from most other reptiles, whose limbs sprawl out to either side.[29] This posture is due to the development of a laterally facing recess in the pelvis (usually an open socket) and a corresponding inwardly facing distinct head on the femur.[30] Their erect posture enabled early dinosaurs to breathe easily while moving, which likely permitted stamina and activity levels that surpassed those of "sprawling" reptiles.[31] Erect limbs probably also helped support the evolution of large size by reducing bending stresses on limbs.[32] Some non-dinosaurian archosaurs, including rauisuchians, also had erect limbs but achieved this by a "pillar-erect" configuration of the hip joint, where instead of having a projection from the femur insert on a socket on the hip, the upper pelvic bone was rotated to form an overhanging shelf.[32]

Evolutionary history

Origins and early evolution

Dinosaurs diverged from their archosaur ancestors during the Middle to Late Triassic epochs, roughly 20 million years after the devastating Permian–Triassic extinction event wiped out an estimated 96% of all marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species approximately 252 million years ago.[33][34] Radiometric dating of the rock formation that contained fossils from the early dinosaur genus Eoraptor at 231.4 million years old establishes its presence in the fossil record at this time.[35] Paleontologists think that Eoraptor resembles the common ancestor of all dinosaurs;[36] if this is true, its traits suggest that the first dinosaurs were small, bipedal predators.[37] The discovery of primitive, dinosaur-like ornithodirans such as Marasuchus and Lagerpeton in Argentinian Middle Triassic strata supports this view; analysis of recovered fossils suggests that these animals were indeed small, bipedal predators. Dinosaurs may have appeared as early as 243 million years ago, as evidenced by remains of the genus Nyasasaurus from that period, though known fossils of these animals are too fragmentary to tell if they are dinosaurs or very close dinosaurian relatives.[38] Paleontologist Max C. Langer et al. (2018) determined that Staurikosaurus from the Santa Maria Formation dates to 233.23 million years ago, making it older in geologic age than Eoraptor.[39]

When dinosaurs appeared, they were not the dominant terrestrial animals. The terrestrial habitats were occupied by various types of archosauromorphs and therapsids, like cynodonts and rhynchosaurs. Their main competitors were the pseudosuchia, such as aetosaurs, ornithosuchids and rauisuchians, which were more successful than the dinosaurs.[40] Most of these other animals became extinct in the Triassic, in one of two events. First, at about 215 million years ago, a variety of basal archosauromorphs, including the protorosaurs, became extinct. This was followed by the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event (about 201 million years ago), that saw the end of most of the other groups of early archosaurs, like aetosaurs, ornithosuchids, phytosaurs, and rauisuchians. Rhynchosaurs and dicynodonts survived (at least in some areas) at least as late as early-mid Norian and late Norian or earliest Rhaetian stages, respectively,[41][42] and the exact date of their extinction is uncertain. These losses left behind a land fauna of crocodylomorphs, dinosaurs, mammals, pterosaurians, and turtles.[6] The first few lines of early dinosaurs diversified through the Carnian and Norian stages of the Triassic, possibly by occupying the niches of the groups that became extinct.[8] Also notably, there was a heightened rate of extinction during the Carnian Pluvial Event.[43]

Evolution and paleobiogeography

Dinosaur evolution after the Triassic follows changes in vegetation and the location of continents. In the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic, the continents were connected as the single landmass Pangaea, and there was a worldwide dinosaur fauna mostly composed of coelophysoid carnivores and early sauropodomorph herbivores.[44] Gymnosperm plants (particularly conifers), a potential food source, radiated in the Late Triassic. Early sauropodomorphs did not have sophisticated mechanisms for processing food in the mouth, and so must have employed other means of breaking down food farther along the digestive tract.[45] The general homogeneity of dinosaurian faunas continued into the Middle and Late Jurassic, where most localities had predators consisting of ceratosaurians, spinosauroids, and carnosaurians, and herbivores consisting of stegosaurian ornithischians and large sauropods. Examples of this include the Morrison Formation of North America and Tendaguru Beds of Tanzania. Dinosaurs in China show some differences, with specialized sinraptorid theropods and unusual, long-necked sauropods like Mamenchisaurus.[44] Ankylosaurians and ornithopods were also becoming more common, but prosauropods had become extinct. Conifers and pteridophytes were the most common plants. Sauropods, like the earlier prosauropods, were not oral processors, but ornithischians were evolving various means of dealing with food in the mouth, including potential cheek-like organs to keep food in the mouth, and jaw motions to grind food.[45] Another notable evolutionary event of the Jurassic was the appearance of true birds, descended from maniraptoran coelurosaurians.[10]

By the Early Cretaceous and the ongoing breakup of Pangaea, dinosaurs were becoming strongly differentiated by landmass. The earliest part of this time saw the spread of ankylosaurians, iguanodontians, and brachiosaurids through Europe, North America, and northern Africa. These were later supplemented or replaced in Africa by large spinosaurid and carcharodontosaurid theropods, and rebbachisaurid and titanosaurian sauropods, also found in South America. In Asia, maniraptoran coelurosaurians like dromaeosaurids, troodontids, and oviraptorosaurians became the common theropods, and ankylosaurids and early ceratopsians like Psittacosaurus became important herbivores. Meanwhile, Australia was home to a fauna of basal ankylosaurians, hypsilophodonts, and iguanodontians.[44] The stegosaurians appear to have gone extinct at some point in the late Early Cretaceous or early Late Cretaceous. A major change in the Early Cretaceous, which would be amplified in the Late Cretaceous, was the evolution of flowering plants. At the same time, several groups of dinosaurian herbivores evolved more sophisticated ways to orally process food. Ceratopsians developed a method of slicing with teeth stacked on each other in batteries, and iguanodontians refined a method of grinding with dental batteries, taken to its extreme in hadrosaurids.[45] Some sauropods also evolved tooth batteries, best exemplified by the rebbachisaurid Nigersaurus.[46]

There were three general dinosaur faunas in the Late Cretaceous. In the northern continents of North America and Asia, the major theropods were tyrannosaurids and various types of smaller maniraptoran theropods, with a predominantly ornithischian herbivore assemblage of hadrosaurids, ceratopsians, ankylosaurids, and pachycephalosaurians. In the southern continents that had made up the now-splitting Gondwana, abelisaurids were the common theropods, and titanosaurian sauropods the common herbivores. Finally, in Europe, dromaeosaurids, rhabdodontid iguanodontians, nodosaurid ankylosaurians, and titanosaurian sauropods were prevalent.[44] Flowering plants were greatly radiating,[45] with the first grasses appearing by the end of the Cretaceous.[47] Grinding hadrosaurids and shearing ceratopsians became extremely diverse across North America and Asia. Theropods were also radiating as herbivores or omnivores, with therizinosaurians and ornithomimosaurians becoming common.[45]

The Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, which occurred approximately 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous, caused the extinction of all dinosaur groups except for the neornithine birds. Some other diapsid groups, such as crocodilians, sebecosuchians, turtles, lizards, snakes, sphenodontians, and choristoderans, also survived the event.[48]

The surviving lineages of neornithine birds, including the ancestors of modern ratites, ducks and chickens, and a variety of waterbirds, diversified rapidly at the beginning of the Paleogene period, entering ecological niches left vacant by the extinction of Mesozoic dinosaur groups such as the arboreal enantiornithines, aquatic hesperornithines, and even the larger terrestrial theropods (in the form of Gastornis, eogruiids, bathornithids, ratites, geranoidids, mihirungs, and "terror birds"). It is often cited that mammals out-competed the neornithines for dominance of most terrestrial niches but many of these groups co-existed with rich mammalian faunas for most of the Cenozoic Era.[49] Terror birds and bathornithids occupied carnivorous guilds alongside predatory mammals,[50][51] and ratites are still fairly successful as mid-sized herbivores; eogruiids similarly lasted from the Eocene to Pliocene, only becoming extinct very recently after over 20 million years of co-existence with many mammal groups.[52]

Classification

Dinosaurs belong to a group known as archosaurs, which also includes modern crocodilians. Within the archosaur group, dinosaurs are differentiated most noticeably by their gait. Dinosaur legs extend directly beneath the body, whereas the legs of lizards and crocodilians sprawl out to either side.[23]

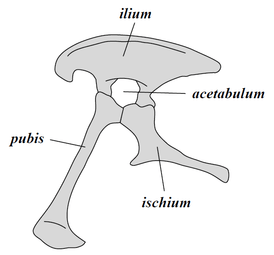

Collectively, dinosaurs as a clade are divided into two primary branches, Saurischia and Ornithischia. Saurischia includes those taxa sharing a more recent common ancestor with birds than with Ornithischia, while Ornithischia includes all taxa sharing a more recent common ancestor with Triceratops than with Saurischia. Anatomically, these two groups can be distinguished most noticeably by their pelvic structure. Early saurischians—"lizard-hipped", from the Greek sauros (σαῦρος) meaning "lizard" and ischion (ἰσχίον) meaning "hip joint"—retained the hip structure of their ancestors, with a pubis bone directed cranially, or forward.[30] This basic form was modified by rotating the pubis backward to varying degrees in several groups (Herrerasaurus,[53] therizinosauroids,[54] dromaeosaurids,[55] and birds[10]). Saurischia includes the theropods (exclusively bipedal and with a wide variety of diets) and sauropodomorphs (long-necked herbivores which include advanced, quadrupedal groups).[22][56]

By contrast, ornithischians—"bird-hipped", from the Greek ornitheios (ὀρνίθειος) meaning "of a bird" and ischion (ἰσχίον) meaning "hip joint"—had a pelvis that superficially resembled a bird's pelvis: the pubic bone was oriented caudally (rear-pointing). Unlike birds, the ornithischian pubis also usually had an additional forward-pointing process. Ornithischia includes a variety of species that were primarily herbivores. (NB: the terms "lizard hip" and "bird hip" are misnomers – birds evolved from dinosaurs with "lizard hips".)[23]

Saurischian pelvis structure (left side)

Saurischian pelvis structure (left side) Tyrannosaurus pelvis (showing saurischian structure – left side)

Tyrannosaurus pelvis (showing saurischian structure – left side) Ornithischian pelvis structure (left side)

Ornithischian pelvis structure (left side) Edmontosaurus pelvis (showing ornithischian structure – left side)

Edmontosaurus pelvis (showing ornithischian structure – left side)

Taxonomy

The following is a simplified classification of dinosaur groups based on their evolutionary relationships, and organized based on the list of Mesozoic dinosaur species provided by Holtz (2007).[57] A more detailed version can be found at Dinosaur classification. The dagger (†) is used to signify groups with no living members.

- Dinosauria

- Saurischia ("lizard-hipped"; includes Theropoda and Sauropodomorpha)

- †Herrerasauria (early bipedal carnivores)

- Theropoda (all bipedal; most were carnivorous)

- †Coelophysoidea (small, early theropods; includes Coelophysis and close relatives)

- †Dilophosauridae (early crested and carnivorous theropods)

- †Ceratosauria (generally elaborately horned, the dominant southern carnivores of the Cretaceous)

- Tetanurae ("stiff tails"; includes most theropods)

- †Megalosauroidea (early group of large carnivores including the semiaquatic spinosaurids)

- †Carnosauria (Allosaurus and close relatives, like Carcharodontosaurus)

- Coelurosauria (feathered theropods, with a range of body sizes and niches)[58]

- †Compsognathidae (common early coelurosaurs with reduced forelimbs)

- †Tyrannosauridae (Tyrannosaurus and close relatives; had reduced forelimbs)

- †Ornithomimosauria ("ostrich-mimics"; mostly toothless; carnivores to possible herbivores)

- †Alvarezsauroidea (small insectivores with reduced forelimbs each bearing one enlarged claw)

- Maniraptora ("hand snatchers"; had long, slender arms and fingers)

- †Therizinosauria (bipedal herbivores with large hand claws and small heads)

- †Oviraptorosauria (mostly toothless; their diet and lifestyle are uncertain)

- †Archaeopterygidae (small, winged theropods or primitive birds)

- †Deinonychosauria (small- to medium-sized; bird-like, with a distinctive toe claw)

- Avialae (modern birds and extinct relatives)

- †Scansoriopterygidae (small primitive avialans with long third fingers)

- †Omnivoropterygidae (large, early short-tailed avialans)

- †Confuciusornithidae (small toothless avialans)

- †Enantiornithes (primitive tree-dwelling, flying avialans)

- Euornithes (advanced flying birds)

- †Yanornithiformes (toothed Cretaceous Chinese birds)

- †Hesperornithes (specialized aquatic diving birds)

- Aves (modern, beaked birds and their extinct relatives)

- †Sauropodomorpha (herbivores with small heads, long necks, long tails)

- †Guaibasauridae (small, primitive, omnivorous sauropodomorphs)

- †Plateosauridae (primitive, strictly bipedal "prosauropods")

- †Riojasauridae (small, primitive sauropodomorphs)

- †Massospondylidae (small, primitive sauropodomorphs)

- †Sauropoda (very large and heavy, usually over 15 m (49 ft) long; quadrupedal)

- †Vulcanodontidae (primitive sauropods with pillar-like limbs)

- †Eusauropoda ("true sauropods")

- †Cetiosauridae ("whale reptiles")

- †Turiasauria (European group of Jurassic and Cretaceous sauropods)

- †Neosauropoda ("new sauropods")

- †Diplodocoidea (skulls and tails elongated; teeth typically narrow and pencil-like)

- †Macronaria (boxy skulls; spoon- or pencil-shaped teeth)

- †Brachiosauridae (long-necked, long-armed macronarians)

- †Titanosauria (diverse; stocky, with wide hips; most common in the Late Cretaceous of southern continents)

- †Ornithischia ("bird-hipped"; diverse bipedal and quadrupedal herbivores)

- †Heterodontosauridae (small basal ornithopod herbivores/omnivores with prominent canine-like teeth)

- †Thyreophora (armored dinosaurs; mostly quadrupeds)

- †Ankylosauria (scutes as primary armor; some had club-like tails)

- †Stegosauria (spikes and plates as primary armor)

- †Neornithischia ("new ornithischians")

- †Ornithopoda (various sizes; bipeds and quadrupeds; evolved a method of chewing using skull flexibility and numerous teeth)

- †Marginocephalia (characterized by a cranial growth)

- †Pachycephalosauria (bipeds with domed or knobby growth on skulls)

- †Ceratopsia (quadrupeds with frills; many also had horns)

Biology

Knowledge about dinosaurs is derived from a variety of fossil and non-fossil records, including fossilized bones, feces, trackways, gastroliths, feathers, impressions of skin, internal organs and soft tissues.[59][60] Many fields of study contribute to our understanding of dinosaurs, including physics (especially biomechanics), chemistry, biology, and the Earth sciences (of which paleontology is a sub-discipline).[61][62] Two topics of particular interest and study have been dinosaur size and behavior.[63]

Size

Current evidence suggests that dinosaur average size varied through the Triassic, Early Jurassic, Late Jurassic and Cretaceous.[36] Predatory theropod dinosaurs, which occupied most terrestrial carnivore niches during the Mesozoic, most often fall into the 100 to 1000 kg (220 to 2200 lb) category when sorted by estimated weight into categories based on order of magnitude, whereas recent predatory carnivoran mammals peak in the 10 to 100 kg (22 to 220 lb) category.[64] The mode of Mesozoic dinosaur body masses is between 1 to 10 tonnes (1.1 to 11.0 short tons).[65] This contrasts sharply with the average size of Cenozoic mammals, estimated by the National Museum of Natural History as about 2 to 5 kg (4.4 to 11.0 lb).[66]

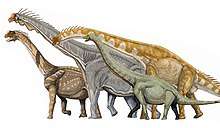

The sauropods were the largest and heaviest dinosaurs. For much of the dinosaur era, the smallest sauropods were larger than anything else in their habitat, and the largest were an order of magnitude more massive than anything else that has since walked the Earth. Giant prehistoric mammals such as Paraceratherium (the largest land mammal ever) were dwarfed by the giant sauropods, and only modern whales approach or surpass them in size.[67] There are several proposed advantages for the large size of sauropods, including protection from predation, reduction of energy use, and longevity, but it may be that the most important advantage was dietary. Large animals are more efficient at digestion than small animals, because food spends more time in their digestive systems. This also permits them to subsist on food with lower nutritive value than smaller animals. Sauropod remains are mostly found in rock formations interpreted as dry or seasonally dry, and the ability to eat large quantities of low-nutrient browse would have been advantageous in such environments.[68]

Largest and smallest

_adult_male_in_flight-cropped.jpg)

Scientists will probably never be certain of the largest and smallest dinosaurs to have ever existed. This is because only a tiny percentage of animals were ever fossilized and most of these remain buried in the earth. Few of the specimens that are recovered are complete skeletons, and impressions of skin and other soft tissues are rare. Rebuilding a complete skeleton by comparing the size and morphology of bones to those of similar, better-known species is an inexact art, and reconstructing the muscles and other organs of the living animal is, at best, a process of educated guesswork.[69]

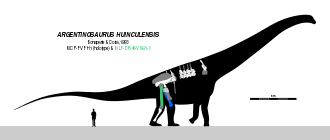

The tallest and heaviest dinosaur known from good skeletons is Giraffatitan brancai (previously classified as a species of Brachiosaurus). Its remains were discovered in Tanzania between 1907 and 1912. Bones from several similar-sized individuals were incorporated into the skeleton now mounted and on display at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin;[70] this mount is 12 meters (39 ft) tall and 21.8–22.5 meters (72–74 ft) long,[71][72] and would have belonged to an animal that weighed between 30000 and 60000 kilograms (70000 and 130000 lb). The longest complete dinosaur is the 27 meters (89 feet) long Diplodocus, which was discovered in Wyoming in the United States and displayed in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 1907.[73] The longest dinosaur known from good fossil material is the Patagotitan: the skeleton mount in the American Museum of Natural History in New York is 37 meters (121 ft) long. The Museo Municipal Carmen Funes in Plaza Huincul, Argentina, has an Argentinosaurus reconstructed skeleton mount 39.7 metres (130 ft) long.[74]

.png)

There were larger dinosaurs, but knowledge of them is based entirely on a small number of fragmentary fossils. Most of the largest herbivorous specimens on record were discovered in the 1970s or later, and include the massive Argentinosaurus, which may have weighed 80000 to 100000 kilograms (90 to 110 short tons) and reached length of 30–40 metres (98–131 ft); some of the longest were the 33.5 meters (110 ft) long Diplodocus hallorum[68] (formerly Seismosaurus), the 33–34 meters (108–112 ft) long Supersaurus[75] and 37 metres (121 ft) long Patagotitan; and the tallest, the 18 meters (59 ft) tall Sauroposeidon, which could have reached a sixth-floor window. The heaviest and longest dinosaur may have been Maraapunisaurus, known only from a now lost partial vertebral neural arch described in 1878. Extrapolating from the illustration of this bone, the animal may have been 58 meters (190 ft) long and weighed 122400 kg (270000 lb).[68] However, as no further evidence of sauropods of this size has been found, and the discoverer, Edward Drinker Cope, had made typographic errors before, it is likely to have been an extreme overestimation.[76]

The largest carnivorous dinosaur was Spinosaurus, reaching a length of 12.6 to 18 meters (41 to 59 ft), and weighing 7 to 20.9 tonnes (7.7 to 23.0 short tons).[77][78] Other large carnivorous theropods included Giganotosaurus, Carcharodontosaurus and Tyrannosaurus.[78] Therizinosaurus and Deinocheirus were among the tallest of the theropods. The largest ornithischian dinosaur was probably the hadrosaurid Shantungosaurus giganteus which measured 16.6 metres (54 ft).[79] The largest individuals may have weighed as much as 16 tonnes (18 short tons).[80]

The smallest dinosaur known is the bee hummingbird,[81] with a length of only 5 cm (2.0 in) and mass of around 1.8 g (0.063 oz).[82] The smallest known non-avialan dinosaurs were about the size of pigeons and were those theropods most closely related to birds.[83] For example, Anchiornis huxleyi is currently the smallest non-avialan dinosaur described from an adult specimen, with an estimated weight of 110 grams[84] and a total skeletal length of 34 cm (1.12 ft).[83][84] The smallest herbivorous non-avialan dinosaurs included Microceratus and Wannanosaurus, at about 60 cm (2.0 ft) long each.[57][85]

Behavior

Many modern birds are highly social, often found living in flocks. There is general agreement that some behaviors that are common in birds, as well as in crocodiles (birds' closest living relatives), were also common among extinct dinosaur groups. Interpretations of behavior in fossil species are generally based on the pose of skeletons and their habitat, computer simulations of their biomechanics, and comparisons with modern animals in similar ecological niches.[61]

The first potential evidence for herding or flocking as a widespread behavior common to many dinosaur groups in addition to birds was the 1878 discovery of 31 Iguanodon bernissartensis, ornithischians that were then thought to have perished together in Bernissart, Belgium, after they fell into a deep, flooded sinkhole and drowned.[86] Other mass-death sites have been discovered subsequently. Those, along with multiple trackways, suggest that gregarious behavior was common in many early dinosaur species. Trackways of hundreds or even thousands of herbivores indicate that duck-billed (hadrosaurids) may have moved in great herds, like the American bison or the African Springbok. Sauropod tracks document that these animals traveled in groups composed of several different species, at least in Oxfordshire, England,[87] although there is no evidence for specific herd structures.[88] Congregating into herds may have evolved for defense, for migratory purposes, or to provide protection for young. There is evidence that many types of slow-growing dinosaurs, including various theropods, sauropods, ankylosaurians, ornithopods, and ceratopsians, formed aggregations of immature individuals. One example is a site in Inner Mongolia that has yielded the remains of over 20 Sinornithomimus, from one to seven years old. This assemblage is interpreted as a social group that was trapped in mud.[89] The interpretation of dinosaurs as gregarious has also extended to depicting carnivorous theropods as pack hunters working together to bring down large prey.[90][91] However, this lifestyle is uncommon among modern birds, crocodiles, and other reptiles, and the taphonomic evidence suggesting mammal-like pack hunting in such theropods as Deinonychus and Allosaurus can also be interpreted as the results of fatal disputes between feeding animals, as is seen in many modern diapsid predators.[92]

The crests and frills of some dinosaurs, like the marginocephalians, theropods and lambeosaurines, may have been too fragile to be used for active defense, and so they were likely used for sexual or aggressive displays, though little is known about dinosaur mating and territorialism. Head wounds from bites suggest that theropods, at least, engaged in active aggressive confrontations.[93]

From a behavioral standpoint, one of the most valuable dinosaur fossils was discovered in the Gobi Desert in 1971. It included a Velociraptor attacking a Protoceratops,[94] providing evidence that dinosaurs did indeed attack each other.[95] Additional evidence for attacking live prey is the partially healed tail of an Edmontosaurus, a hadrosaurid dinosaur; the tail is damaged in such a way that shows the animal was bitten by a tyrannosaur but survived.[95] Cannibalism amongst some species of dinosaurs was confirmed by tooth marks found in Madagascar in 2003, involving the theropod Majungasaurus.[96]

Comparisons between the scleral rings of dinosaurs and modern birds and reptiles have been used to infer daily activity patterns of dinosaurs. Although it has been suggested that most dinosaurs were active during the day, these comparisons have shown that small predatory dinosaurs such as dromaeosaurids, Juravenator, and Megapnosaurus were likely nocturnal. Large and medium-sized herbivorous and omnivorous dinosaurs such as ceratopsians, sauropodomorphs, hadrosaurids, ornithomimosaurs may have been cathemeral, active during short intervals throughout the day, although the small ornithischian Agilisaurus was inferred to be diurnal.[97]

Based on current fossil evidence from dinosaurs such as Oryctodromeus, some ornithischian species seem to have led a partially fossorial (burrowing) lifestyle.[98] Many modern birds are arboreal (tree climbing), and this was also true of many Mesozoic birds, especially the enantiornithines.[99] While some early bird-like species may have already been arboreal as well (including dromaeosaurids such as Microraptor[100]) most non-avialan dinosaurs seem to have relied on land-based locomotion. A good understanding of how dinosaurs moved on the ground is key to models of dinosaur behavior; the science of biomechanics, pioneered by Robert McNeill Alexander, has provided significant insight in this area. For example, studies of the forces exerted by muscles and gravity on dinosaurs' skeletal structure have investigated how fast dinosaurs could run,[61] whether diplodocids could create sonic booms via whip-like tail snapping,[101] and whether sauropods could float.[102]

Communication

Modern birds are known to communicate using visual and auditory signals, and the wide diversity of visual display structures among fossil dinosaur groups, such as horns, frills, crests, sails and feathers, suggests that visual communication has always been important in dinosaur biology.[103] Reconstruction of the plumage color of Anchiornis huxleyi, suggest the importance of color in visual communication in non-avian dinosaurs.[104] The evolution of dinosaur vocalization is less certain. Paleontologist Phil Senter suggests that non-avian dinosaurs relied mostly on visual displays and possibly non-vocal acoustic sounds like hissing, jaw grinding or clapping, splashing and wing beating (possible in winged maniraptoran dinosaurs). He states they were unlikely to have been capable of vocalizing since their closest relatives, crocodilians and birds, use different means to vocalize, the former via the larynx and the latter through the unique syrinx, suggesting they evolved independently and their common ancestor was mute.[103]

The earliest remains of a syrinx, which has enough mineral content for fossilization, was found in a specimen of the duck-like Vegavis iaai dated 69-66 million year ago, and this organ is unlikely to have existed in non-avian dinosaurs. However, in contrast to Senter, the researchers have suggested that dinosaurs could vocalize and that the syrinx-based vocal system of birds evolved from a larynx-based one, rather than the two systems evolving independently.[105] A 2016 study suggests that dinosaurs produced closed mouth vocalizations like cooing, which occur in both crocodilians and birds as well as other reptiles. Such vocalizations evolved independently in extant archosaurs numerous times, following increases in body size.[106] The crests of the Lambeosaurini and nasal chambers of ankylosaurids have been suggested to function in vocal resonance,[107][108] though Senter states that the presence of resonance chambers in some dinosaurs is not necessarily evidence of vocalization as modern snakes have such chambers which intensify their hisses.[103]

Reproductive biology

All dinosaurs laid amniotic eggs with hard shells made mostly of calcium carbonate.[109] Dinosaur eggs were usually laid in a nest. Most species create somewhat elaborate nests which can be cups, domes, plates, beds scrapes, mounds, or burrows.[110] Some species of modern bird have no nests; the cliff-nesting common guillemot lays its eggs on bare rock, and male emperor penguins keep eggs between their body and feet. Primitive birds and many non-avialan dinosaurs often lay eggs in communal nests, with males primarily incubating the eggs. While modern birds have only one functional oviduct and lay one egg at a time, more primitive birds and dinosaurs had two oviducts, like crocodiles. Some non-avialan dinosaurs, such as Troodon, exhibited iterative laying, where the adult might lay a pair of eggs every one or two days, and then ensured simultaneous hatching by delaying brooding until all eggs were laid.[111]

When laying eggs, females grow a special type of bone between the hard outer bone and the marrow of their limbs. This medullary bone, which is rich in calcium, is used to make eggshells. A discovery of features in a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton provided evidence of medullary bone in extinct dinosaurs and, for the first time, allowed paleontologists to establish the sex of a fossil dinosaur specimen. Further research has found medullary bone in the carnosaur Allosaurus and the ornithopod Tenontosaurus. Because the line of dinosaurs that includes Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus diverged from the line that led to Tenontosaurus very early in the evolution of dinosaurs, this suggests that the production of medullary tissue is a general characteristic of all dinosaurs.[112]

Another widespread trait among modern birds (but see below in regards to fossil groups and extant megapodes) is parental care for young after hatching. Jack Horner's 1978 discovery of a Maiasaura ("good mother lizard") nesting ground in Montana demonstrated that parental care continued long after birth among ornithopods.[113] A specimen of the Mongolian oviraptorid Citipati osmolskae was discovered in a chicken-like brooding position in 1993,[114] which may indicate that they had begun using an insulating layer of feathers to keep the eggs warm.[115] A dinosaur embryo (pertaining to the prosauropod Massospondylus) was found without teeth, indicating that some parental care was required to feed the young dinosaurs.[116] Trackways have also confirmed parental behavior among ornithopods from the Isle of Skye in northwestern Scotland.[117]

However, there is ample evidence of precociality or superprecociality among many dinosaur species, particularly theropods. For instance, non-ornithuromorph birds have been abundantly demonstrated to have had slow growth rates, megapode-like egg burying behavior and the ability to fly soon after birth.[118][119][120][121] Both Tyrannosaurus rex and Troodon formosus display juveniles with clear superprecociality and likely occupying different ecological niches than the adults.[111] Superprecociality has been inferred for sauropods.[122]

Physiology

Because both modern crocodilians and birds have four-chambered hearts (albeit modified in crocodilians), it is likely that this is a trait shared by all archosaurs, including all dinosaurs.[123] While all modern birds have high metabolisms and are "warm-blooded" (endothermic), a vigorous debate has been ongoing since the 1960s regarding how far back in the dinosaur lineage this trait extends. Scientists disagree as to whether non-avian dinosaurs were endothermic, ectothermic, or some combination of both.[124]

After non-avian dinosaurs were discovered, paleontologists first posited that they were ectothermic. This supposed "cold-bloodedness" was used to imply that the ancient dinosaurs were relatively slow, sluggish organisms, even though many modern reptiles are fast and light-footed despite relying on external sources of heat to regulate their body temperature. The idea of dinosaurs as ectothermic remained a prevalent view until Robert T. "Bob" Bakker, an early proponent of dinosaur endothermy, published an influential paper on the topic in 1968.[125][126]

Modern evidence indicates that some non-avian dinosaurs thrived in cooler temperate climates and that some early species must have regulated their body temperature by internal biological means (aided by the animals' bulk in large species and feathers or other body coverings in smaller species). Evidence of endothermy in Mesozoic dinosaurs includes the discovery of polar dinosaurs in Australia and Antarctica as well as analysis of blood-vessel structures within fossil bones that are typical of endotherms. Scientific debate continues regarding the specific ways in which dinosaur temperature regulation evolved.[127][128]

In saurischian dinosaurs, higher metabolisms were supported by the evolution of the avian respiratory system, characterized by an extensive system of air sacs that extended the lungs and invaded many of the bones in the skeleton, making them hollow.[129] Early avian-style respiratory systems with air sacs may have been capable of sustaining higher activity levels than those of mammals of similar size and build. In addition to providing a very efficient supply of oxygen, the rapid airflow would have been an effective cooling mechanism, which is essential for animals that are active but too large to get rid of all the excess heat through their skin.[130]

Like other reptiles, dinosaurs are primarily uricotelic, that is, their kidneys extract nitrogenous wastes from their bloodstream and excrete it as uric acid instead of urea or ammonia via the ureters into the intestine. In most living species, uric acid is excreted along with feces as a semisolid waste.[131][132][133] However, at least some modern birds (such as hummingbirds) can be facultatively ammonotelic, excreting most of the nitrogenous wastes as ammonia.[134] This material, as well as the output of the intestines, emerges from the cloaca.[135][136] In addition, many species regurgitate pellets, and fossil pellets that may have come from dinosaurs are known from as long ago as the Cretaceous.[137]

Origin of birds

The possibility that dinosaurs were the ancestors of birds was first suggested in 1868 by Thomas Henry Huxley.[138] After the work of Gerhard Heilmann in the early 20th century, the theory of birds as dinosaur descendants was abandoned in favor of the idea of their being descendants of generalized thecodonts, with the key piece of evidence being the supposed lack of clavicles in dinosaurs.[139] However, as later discoveries showed, clavicles (or a single fused wishbone, which derived from separate clavicles) were not actually absent;[10] they had been found as early as 1924 in Oviraptor, but misidentified as an interclavicle.[140] In the 1970s, John Ostrom revived the dinosaur–bird theory,[141] which gained momentum in the coming decades with the advent of cladistic analysis,[142] and a great increase in the discovery of small theropods and early birds.[25] Of particular note have been the fossils of the Yixian Formation, where a variety of theropods and early birds have been found, often with feathers of some type.[58][10] Birds share over a hundred distinct anatomical features with theropod dinosaurs, which are now generally accepted to have been their closest ancient relatives.[143] They are most closely allied with maniraptoran coelurosaurs.[10] A minority of scientists, most notably Alan Feduccia and Larry Martin, have proposed other evolutionary paths, including revised versions of Heilmann's basal archosaur proposal,[144] or that maniraptoran theropods are the ancestors of birds but themselves are not dinosaurs, only convergent with dinosaurs.[145]

Feathers

Feathers are one of the most recognizable characteristics of modern birds, and a trait that was shared by all other dinosaur groups. Based on the current distribution of fossil evidence, it appears that feathers were an ancestral dinosaurian trait, though one that may have been selectively lost in some species.[146] Direct fossil evidence of feathers or feather-like structures has been discovered in a diverse array of species in many non-avian dinosaur groups,[58] both among saurischians and ornithischians. Simple, branched, feather-like structures are known from heterodontosaurids, primitive neornithischians[147] and theropods,[148] and primitive ceratopsians. Evidence for true, vaned feathers similar to the flight feathers of modern birds has been found only in the theropod subgroup Maniraptora, which includes oviraptorosaurs, troodontids, dromaeosaurids, and birds.[10][149] Feather-like structures known as pycnofibres have also been found in pterosaurs,[150] suggesting the possibility that feather-like filaments may have been common in the bird lineage and evolved before the appearance of dinosaurs themselves.[146] Research into the genetics of American alligators has also revealed that crocodylian scutes do possess feather-keratins during embryonic development, but these keratins are not expressed by the animals before hatching.[151]

Archaeopteryx was the first fossil found that revealed a potential connection between dinosaurs and birds. It is considered a transitional fossil, in that it displays features of both groups. Brought to light just two years after Charles Darwin's seminal On the Origin of Species (1859), its discovery spurred the nascent debate between proponents of evolutionary biology and creationism. This early bird is so dinosaur-like that, without a clear impression of feathers in the surrounding rock, at least one specimen was mistaken for Compsognathus.[152] Since the 1990s, a number of additional feathered dinosaurs have been found, providing even stronger evidence of the close relationship between dinosaurs and modern birds. Most of these specimens were unearthed in the lagerstätte of the Yixian Formation, Liaoning, northeastern China, which was part of an island continent during the Cretaceous. Though feathers have been found in only a few locations, it is possible that non-avian dinosaurs elsewhere in the world were also feathered. The lack of widespread fossil evidence for feathered non-avian dinosaurs may be because delicate features like skin and feathers are not often preserved by fossilization and thus are absent from the fossil record.[153]

The description of feathered dinosaurs has not been without controversy; perhaps the most vocal critics have been Alan Feduccia and Theagarten Lingham-Soliar, who have proposed that some purported feather-like fossils are the result of the decomposition of collagenous fiber that underlaid the dinosaurs' skin,[154][155][156] and that maniraptoran dinosaurs with vaned feathers were not actually dinosaurs, but convergent with dinosaurs.[145][155] However, their views have for the most part not been accepted by other researchers, to the point that the scientific nature of Feduccia's proposals has been questioned.[157]

In 2016, it was reported that a dinosaur tail with feathers had been found enclosed in amber. The fossil is about 99 million years old.[58][158][159]

Skeleton

Because feathers are often associated with birds, feathered dinosaurs are often touted as the missing link between birds and dinosaurs. However, the multiple skeletal features also shared by the two groups represent another important line of evidence for paleontologists. Areas of the skeleton with important similarities include the neck, pubis, wrist (semi-lunate carpal), arm and pectoral girdle, furcula (wishbone), and breast bone. Comparison of bird and dinosaur skeletons through cladistic analysis strengthens the case for the link.[160]

Soft anatomy

Large meat-eating dinosaurs had a complex system of air sacs similar to those found in modern birds, according to a 2005 investigation led by Patrick M. O'Connor. The lungs of theropod dinosaurs (carnivores that walked on two legs and had bird-like feet) likely pumped air into hollow sacs in their skeletons, as is the case in birds. "What was once formally considered unique to birds was present in some form in the ancestors of birds", O'Connor said.[161][162] In 2008, scientists described Aerosteon riocoloradensis, the skeleton of which supplies the strongest evidence to date of a dinosaur with a bird-like breathing system. CT scanning of Aerosteon's fossil bones revealed evidence for the existence of air sacs within the animal's body cavity.[129][163]

Behavioral evidence

Fossils of the troodonts Mei and Sinornithoides demonstrate that some dinosaurs slept with their heads tucked under their arms.[164] This behavior, which may have helped to keep the head warm, is also characteristic of modern birds. Several deinonychosaur and oviraptorosaur specimens have also been found preserved on top of their nests, likely brooding in a bird-like manner.[165] The ratio between egg volume and body mass of adults among these dinosaurs suggest that the eggs were primarily brooded by the male, and that the young were highly precocial, similar to many modern ground-dwelling birds.[166]

Some dinosaurs are known to have used gizzard stones like modern birds. These stones are swallowed by animals to aid digestion and break down food and hard fibers once they enter the stomach. When found in association with fossils, gizzard stones are called gastroliths.[167]

Extinction of major groups

The discovery that birds are a type of dinosaur showed that dinosaurs in general are not, in fact, extinct as is commonly stated.[168] However, all non-avian dinosaurs, estimated to have been 628-1078 species,[169] as well as many groups of birds did suddenly become extinct approximately 66 million years ago. It has been suggested that because small mammals, squamata and birds occupied the ecological niches suited for small body size, non-avian dinosaurs never evolved a diverse fauna of small-bodied species, which led to their downfall when large-bodied terrestrial tetrapods were hit by the mass extinction event.[170] Many other groups of animals also became extinct at this time, including ammonites (nautilus-like mollusks), mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, and many groups of mammals.[21] Significantly, the insects suffered no discernible population loss, which left them available as food for other survivors. This mass extinction is known as the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. The nature of the event that caused this mass extinction has been extensively studied since the 1970s; at present, several related theories are supported by paleontologists. Though the consensus is that an impact event was the primary cause of dinosaur extinction, some scientists cite other possible causes, or support the idea that a confluence of several factors was responsible for the sudden disappearance of dinosaurs from the fossil record.[171][172][21]

Impact event

The asteroid impact hypothesis, which was brought to wide attention in 1980 by Walter Alvarez and colleagues, links the extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous to a bolide impact approximately 66 million years ago.[173] Alvarez et al. proposed that a sudden increase in iridium levels, recorded around the world in the period's rock stratum, was direct evidence of the impact.[174] The bulk of the evidence now suggests that a bolide 5 to 15 kilometers (3.1 to 9.3 miles) wide hit in the vicinity of the Yucatán Peninsula (in southeastern Mexico), creating the approximately 180 km (110 mi) Chicxulub crater and triggering the mass extinction.[175][176] Scientists are not certain whether dinosaurs were thriving or declining before the impact event. Some scientists propose that the meteorite impact caused a long and unnatural drop in Earth's atmospheric temperature, while others claim that it would have instead created an unusual heat wave. The consensus among scientists who support this hypothesis is that the impact caused extinctions both directly (by heat from the meteorite impact) and also indirectly (via a worldwide cooling brought about when matter ejected from the impact crater reflected thermal radiation from the sun). Although the speed of extinction cannot be deduced from the fossil record alone, various models suggest that the extinction was extremely rapid, being down to hours rather than years.[177] In 2019, scientists drilling into the seafloor off Mexico extracted a unique geologic record of what they believe to be the day a city-sized asteroid smashed into the planet.[178]

Deccan Traps

Before 2000, arguments that the Deccan Traps flood basalts caused the extinction were usually linked to the view that the extinction was gradual, as the flood basalt events were thought to have started around 68 million years ago and lasted for over 2 million years. However, there is evidence that two thirds of the Deccan Traps were created in only 1 million years about 66 million years ago, and so these eruptions would have caused a fairly rapid extinction, possibly over a period of thousands of years, but still longer than would be expected from a single impact event.[179][180]

The Deccan Traps in India could have caused extinction through several mechanisms, including the release into the air of dust and sulfuric aerosols, which might have blocked sunlight and thereby reduced photosynthesis in plants. In addition, Deccan Trap volcanism might have resulted in carbon dioxide emissions, which would have increased the greenhouse effect when the dust and aerosols cleared from the atmosphere.[180] Before the mass extinction of the dinosaurs, the release of volcanic gases during the formation of the Deccan Traps "contributed to an apparently massive global warming. Some data point to an average rise in temperature of [8 °C (14 °F)] in the last half-million years before the impact [at Chicxulub]."[181][179][180]

In the years when the Deccan Traps hypothesis was linked to a slower extinction, Luis Alvarez (who died in 1988) replied that paleontologists were being misled by sparse data. While his assertion was not initially well-received, later intensive field studies of fossil beds lent weight to his claim. Eventually, most paleontologists began to accept the idea that the mass extinctions at the end of the Cretaceous were largely or at least partly due to a massive Earth impact. However, even Walter Alvarez has acknowledged that there were other major changes on Earth even before the impact, such as a drop in sea level and massive volcanic eruptions that produced the Indian Deccan Traps, and these may have contributed to the extinctions.[182]

Possible Paleocene survivors

Non-avian dinosaur remains are occasionally found above the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary. In 2000, paleontologist Spencer G. Lucas et al. reported the discovery of a single hadrosaur right femur in the San Juan Basin, New Mexico, and described it as evidence of Paleocene dinosaurs. The formation in which the bone was discovered has been dated to the early Paleocene epoch, approximately 64.5 million years ago. If the bone was not re-deposited into that stratum by weathering action, it would provide evidence that some dinosaur populations may have survived at least a half-million years into the Cenozoic.[183] Other evidence includes the finding of dinosaur remains in the Hell Creek Formation up to 1.3 m (51 in) above the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, representing 40000 years of elapsed time. Similar reports have come from other parts of the world, including China.[184] Many scientists, however, dismissed the supposed Paleocene dinosaurs as re-worked, that is, washed out of their original locations and then re-buried in much later sediments.[185][186] Direct dating of the bones themselves has supported the later date, with uranium–lead dating methods resulting in a precise age of 64.8 ± 0.9 million years ago.[187] If correct, the presence of a handful of dinosaurs in the early Paleocene would not change the underlying facts of the extinction.[185]

History of study

Dinosaur fossils have been known for millennia, although their true nature was not recognized. The Chinese considered them to be dragon bones and documented them as such. For example, Huayang Guo Zhi (華陽國志), a gazetteer compiled by Chang Qu (常璩) during the Western Jin Dynasty (265–316), reported the discovery of dragon bones at Wucheng in Sichuan Province.[188] Villagers in central China have long unearthed fossilized "dragon bones" for use in traditional medicines, a practice that continues as of 2020.[189] In Europe, dinosaur fossils were generally believed to be the remains of giants and other biblical creatures.[190]

Scholarly descriptions of what would now be recognized as dinosaur bones first appeared in the late 17th century in England. Part of a bone, now known to have been the femur of a Megalosaurus,[191] was recovered from a limestone quarry at Cornwell near Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, in 1676. The fragment was sent to Robert Plot, Professor of Chemistry at the University of Oxford and first curator of the Ashmolean Museum, who published a description in his The Natural History of Oxford-shire (1677).[192] He correctly identified the bone as the lower extremity of the femur of a large animal, and recognized that it was too large to belong to any known species. He therefore concluded it to be the femur of a huge human, perhaps a Titan or another type of giant featured in legends.[193][194] Edward Lhuyd, a friend of Sir Isaac Newton, published Lithophylacii Britannici ichnographia (1699), the first scientific treatment of what would now be recognized as a dinosaur when he described and named a sauropod tooth, Rutellum impicatum,[195][196] that had been found in Caswell, near Witney, Oxfordshire.[197]

Between 1815 and 1824, the Rev William Buckland, the first Reader of Geology at the University of Oxford, collected more fossilized bones of Megalosaurus and became the first person to describe a dinosaur in a scientific journal.[191][198] The second dinosaur genus to be identified, Iguanodon, was discovered in 1822 by Mary Ann Mantell – the wife of English geologist Gideon Mantell. Gideon Mantell recognized similarities between his fossils and the bones of modern iguanas. He published his findings in 1825.[199][200]

The study of these "great fossil lizards" soon became of great interest to European and American scientists, and in 1842 the English paleontologist Richard Owen coined the term "dinosaur". He recognized that the remains that had been found so far, Iguanodon, Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus, shared a number of distinctive features, and so decided to present them as a distinct taxonomic group. With the backing of Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, Owen established the Natural History Museum, London, to display the national collection of dinosaur fossils and other biological and geological exhibits.[201]

In 1858, William Parker Foulke discovered the first known American dinosaur, in marl pits in the small town of Haddonfield, New Jersey. (Although fossils had been found before, their nature had not been correctly discerned.) The creature was named Hadrosaurus foulkii. It was an extremely important find: Hadrosaurus was one of the first nearly complete dinosaur skeletons found (the first was in 1834, in Maidstone, England), and it was clearly a bipedal creature. This was a revolutionary discovery as, until that point, most scientists had believed dinosaurs walked on four feet, like other lizards. Foulke's discoveries sparked a wave of interests in dinosaurs in the United States, known as dinosaur mania.[202]

Dinosaur mania was exemplified by the fierce rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, both of whom raced to be the first to find new dinosaurs in what came to be known as the Bone Wars. The feud probably originated when Marsh publicly pointed out that Cope's reconstruction of an Elasmosaurus skeleton was flawed: Cope had inadvertently placed the plesiosaur's head at what should have been the animal's tail end. The fight between the two scientists lasted for over 30 years, ending in 1897 when Cope died after spending his entire fortune on the dinosaur hunt. Unfortunately, many valuable dinosaur specimens were damaged or destroyed due to the pair's rough methods: for example, their diggers often used dynamite to unearth bones (a method modern paleontologists would find appalling because the explosions from the dynamic would potentially destroy any and all dinosauric evidence). Despite their unrefined methods, the contributions of Cope and Marsh to paleontology were vast: Marsh unearthed 86 new species of dinosaur and Cope discovered 56, a total of 142 new species. Cope's collection is now at the American Museum of Natural History, while Marsh's is on display at the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University.[203]

After 1897, the search for dinosaur fossils extended to every continent, including Antarctica. The first Antarctic dinosaur to be discovered, the ankylosaurid Antarctopelta oliveroi, was found on James Ross Island in 1986,[204] although it was 1994 before an Antarctic species, the theropod Cryolophosaurus ellioti, was formally named and described in a scientific journal.[205]

Current dinosaur "hot spots" include southern South America (especially Argentina) and China. China in particular has produced many exceptional feathered dinosaur specimens due to the unique geology of its dinosaur beds, as well as an ancient arid climate particularly conducive to fossilization.[153]

"Dinosaur renaissance"

The field of dinosaur research has enjoyed a surge in activity that began in the 1970s and is ongoing. This was triggered, in part, by John Ostrom's discovery of Deinonychus, an active predator that may have been warm-blooded, in marked contrast to the then-prevailing image of dinosaurs as sluggish and cold-blooded. Vertebrate paleontology has become a global science. Major new dinosaur discoveries have been made by paleontologists working in previously unexploited regions, including India, South America, Madagascar, Antarctica, and most significantly China (the well-preserved feathered dinosaurs[58] in China have further consolidated the link between dinosaurs and their living descendants, modern birds). The widespread application of cladistics, which rigorously analyzes the relationships between biological organisms, has also proved tremendously useful in classifying dinosaurs. Cladistic analysis, among other modern techniques, helps to compensate for an often incomplete and fragmentary fossil record.[206]

| Timeline of notable dinosaur taxonomic descriptions |

|---|

|

Soft tissue and DNA

One of the best examples of soft-tissue impressions in a fossil dinosaur was discovered in the Pietraroia Plattenkalk in southern Italy. The discovery was reported in 1998, and described the specimen of a small, very young coelurosaur, Scipionyx samniticus. The fossil includes portions of the intestines, colon, liver, muscles, and windpipe of this immature dinosaur.[59]

In the March 2005 issue of Science, the paleontologist Mary Higby Schweitzer and her team announced the discovery of flexible material resembling actual soft tissue inside a 68-million-year-old Tyrannosaurus rex leg bone from the Hell Creek Formation in Montana. After recovery, the tissue was rehydrated by the science team.[60] When the fossilized bone was treated over several weeks to remove mineral content from the fossilized bone-marrow cavity (a process called demineralization), Schweitzer found evidence of intact structures such as blood vessels, bone matrix, and connective tissue (bone fibers). Scrutiny under the microscope further revealed that the putative dinosaur soft tissue had retained fine structures (microstructures) even at the cellular level. The exact nature and composition of this material, and the implications of Schweitzer's discovery, are not yet clear.[60]

In 2009, a team including Schweitzer announced that, using even more careful methodology, they had duplicated their results by finding similar soft tissue in a duck-billed dinosaur, Brachylophosaurus canadensis, found in the Judith River Formation of Montana. This included even more detailed tissue, down to preserved bone cells that seem even to have visible remnants of nuclei and what seem to be red blood cells. Among other materials found in the bone was collagen, as in the Tyrannosaurus bone. The type of collagen an animal has in its bones varies according to its DNA and, in both cases, this collagen was of the same type found in modern chickens and ostriches.[207]

The extraction of ancient DNA from dinosaur fossils has been reported on two separate occasions;[208] upon further inspection and peer review, however, neither of these reports could be confirmed.[209] However, a functional peptide involved in the vision of a theoretical dinosaur has been inferred using analytical phylogenetic reconstruction methods on gene sequences of related modern species such as reptiles and birds.[210] In addition, several proteins, including hemoglobin,[211] have putatively been detected in dinosaur fossils.[212][213]

In 2015, researchers reported finding structures similar to blood cells and collagen fibers, preserved in the bone fossils of six Cretaceous dinosaur specimens, which are approximately 75 million years old.[214][215]

Cultural depictions

By human standards, dinosaurs were creatures of fantastic appearance and often enormous size. As such, they have captured the popular imagination and become an enduring part of human culture. Entry of the word "dinosaur" into the common vernacular reflects the animals' cultural importance: in English, "dinosaur" is commonly used to describe anything that is impractically large, obsolete, or bound for extinction.[216]

Public enthusiasm for dinosaurs first developed in Victorian England, where in 1854, three decades after the first scientific descriptions of dinosaur remains, a menagerie of lifelike dinosaur sculptures was unveiled in London's Crystal Palace Park. The Crystal Palace dinosaurs proved so popular that a strong market in smaller replicas soon developed. In subsequent decades, dinosaur exhibits opened at parks and museums around the world, ensuring that successive generations would be introduced to the animals in an immersive and exciting way.[217] Dinosaurs' enduring popularity, in its turn, has resulted in significant public funding for dinosaur science, and has frequently spurred new discoveries. In the United States, for example, the competition between museums for public attention led directly to the Bone Wars of the 1880s and 1890s, during which a pair of feuding paleontologists made enormous scientific contributions.[218]

The popular preoccupation with dinosaurs has ensured their appearance in literature, film, and other media. Beginning in 1852 with a passing mention in Charles Dickens' Bleak House,[219] dinosaurs have been featured in large numbers of fictional works. Jules Verne's 1864 novel Journey to the Center of the Earth, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's 1912 book The Lost World, the iconic 1933 film King Kong, the 1954 Godzilla and its many sequels, the best-selling 1990 novel Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton and its 1993 film adaptation are just a few notable examples of dinosaur appearances in fiction. Authors of general-interest non-fiction works about dinosaurs, including some prominent paleontologists, have often sought to use the animals as a way to educate readers about science in general. Dinosaurs are ubiquitous in advertising; numerous companies have referenced dinosaurs in printed or televised advertisements, either in order to sell their own products or in order to characterize their rivals as slow-moving, dim-witted, or obsolete.[220]

See also

- Animal track

- Dinosaur diet and feeding

- Evolutionary history of life

- Lists of dinosaur-bearing stratigraphic units

- List of dinosaur genera

- List of informally named dinosaurs

Notes

- Although dinosaurs are reptiles, views on them as being cold-blooded animals have changed in recent years; see § Physiology for more details.

References

- Owen 1842, p.103: "The combination of such characters … will, it is presumed, be deemed sufficient ground for establishing a distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles, for which I would propose the name of Dinosauria*. (*Gr. δεινός, fearfully great; σαύρος, a lizard. … )

- "Dinosauria". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- Crane, George R. (ed.). "Greek Dictionary Headword Search Results". Perseus 4.0. Medford and Somerville, MA: Tufts University. Retrieved 2019-10-13. Lemma for 'δεινός' from Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon (1940): 'fearful, terrible'.

- Farlow & Brett-Surman 1997, pp. ix–xi, Preface, "Dinosaurs: The Terrestrial Superlative" by James O. Farlow and M.K. Brett-Surman.

- Chamary, JV (September 30, 2014). "Dinosaurs, Pterosaurs And Other Saurs – Big Differences". Forbes.com. Jersey City, NJ: Forbes Media, LLC. ISSN 0015-6914. Archived from the original on 2014-11-10. Retrieved 2018-10-02.

- Weishampel, Dodson & Osmólska 2004, pp. 7–19, chpt. 1: "Origin and Relationships of Dinosauria" by Michael J. Benton.

- Olshevsky 2000

- Langer, Max C.; Ezcurra, Martin D.; Bittencourt, Jonathas S.; Novas, Fernando E. (February 2010). "The origin and early evolution of dinosaurs". Biological Reviews. Cambridge: Cambridge Philosophical Society. 85 (1): 65–66, 82. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.2009.00094.x. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 19895605.

- "Using the tree for classification". Understanding Evolution. Berkeley: University of California. Archived from the original on 2019-08-31. Retrieved 2019-10-14.

- Weishampel, Dodson & Osmólska 2004, pp. 210–231, chpt. 11: "Basal Avialae" by Kevin Padian.

- Wade, Nicholas (March 22, 2017). "Shaking Up the Dinosaur Family Tree". The New York Times. New York: The New York Times Company. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2018-04-07. Retrieved 2019-10-30. "A version of this article appears in print on March 28, 2017, on Page D6 of the New York edition with the headline: Shaking Up the Dinosaur Family Tree."

- Baron, Matthew G.; Norman, David B.; Barrett, Paul M. (March 22, 2017). "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution". Nature. London: Nature Research. 543 (7646): 501–506. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..501B. doi:10.1038/nature21700. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28332513. "This file contains Supplementary Text and Data, Supplementary Tables 1-3 and additional references.": Supplementary Information

- Glut 1997, p. 40

- Lambert & The Diagram Group 1990, p. 288

- Farlow & Brett-Surman 1997, pp. 607–624, chpt. 39: "Major Groups of Non-Dinosaurian Vertebrates of the Mesozoic Era" by Michael Morales.

- Wang, Steve C.; Dodson, Peter (September 12, 2006). "Estimating the diversity of dinosaurs". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 103 (37): 13601–13605. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10313601W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606028103. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1564218. PMID 16954187.

- Russell, Dale A. (1995). "China and the lost worlds of the dinosaurian era". Historical Biology. Milton Park, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. 10 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1080/10292389509380510. ISSN 0891-2963.

- Amos, Jonathan (September 17, 2008). "Will the real dinosaurs stand up?". BBC News. London: BBC. Archived from the original on 2008-09-18. Retrieved 2019-10-16.