Ottawa

Ottawa (/ˈɒtəwə/ (![]()

Ottawa | |

|---|---|

| City of Ottawa • Ville d'Ottawa | |

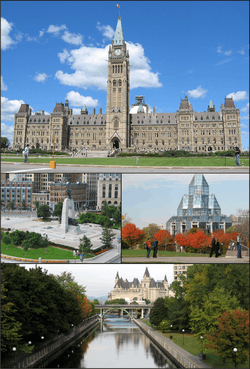

Centre Block on Parliament Hill, the National War Memorial in downtown Ottawa, the National Gallery of Canada, and the Rideau Canal with Château Laurier | |

Flag  Coat of arms Wordmark | |

Nickname(s):

| |

| Motto(s): "Advance-Ottawa-En Avant" Written in the two official languages.[2] | |

Ottawa Location within Ontario  Ottawa Location within Canada  Ottawa Location within North America | |

| Coordinates: 45°25′29″N 75°41′42″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| Region | National Capital Region |

| Established | 1826 as Bytown[3] |

| Incorporated | 1855 as City of Ottawa[3] |

| Amalgamated | 1 January 2001 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Single-tier municipality with a Mayor–council system |

| • Mayor | Jim Watson |

| • City council | Ottawa City Council |

| • Federal representation | List of MPs

|

| • Provincial representation | List of MPPs

|

| Area | |

| • Federal capital city | 2,790.30 km2 (1,077.34 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 520.82 km2 (201.09 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 6,767.41 km2 (2,612.91 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 70 m (230 ft) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Federal capital city | 934,243[7] |

| • Density | 334/km2 (870/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 989,567[8] |

| • Urban density | 1,900/km2 (5,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,323,783 (5th) |

| • Metro density | 195/km2 (510/sq mi) |

| • Demonym[9][10] | Ottawan |

| Time zone | UTC-05:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-04:00 (EDT) |

| Postal code span | K0A-K4C[2] |

| Area codes | 613, 343 |

| GDP | US$ 58.2 billion[11] |

| GDP per capita | US$44,149[11] |

| Website | Ottawa.ca |

Founded in 1826 as Bytown, and incorporated as Ottawa in 1855, the city has evolved into the political centre of Canada. Its original boundaries were expanded through numerous annexations and were ultimately replaced by a new city incorporation and amalgamation in 2001 which significantly increased its land area. The city name "Ottawa" was chosen in reference to the Ottawa River, the name of which is derived from the Algonquin Odawa, meaning "to trade".[14]

Ottawa has the most educated population among Canadian cities[15] and is home to a number of post-secondary, research, and cultural institutions, including the National Arts Centre, the National Gallery, and numerous national museums.

History

With the draining of the Champlain Sea around ten thousand years ago, the Ottawa Valley became habitable.[16] Local populations used the area for wild edible harvesting, hunting, fishing, trade, travel, and camps for over 6500 years. The Ottawa river valley has archeological sites with arrow heads, pottery, and stone tools. Three major rivers meet within Ottawa, making it an important trade and travel area for thousands of years.[17] The Algonquins called the Ottawa River Kichi Sibi or Kichissippi meaning "Great River" or "Grand River".[18][19][20][21]

Étienne Brûlé, widely regarded as the first European to travel up the Ottawa River, passed by Ottawa in 1610 on his way to the Great Lakes.[19] Three years later, Samuel de Champlain wrote about the waterfalls in the area and about his encounters with the Algonquins, who had been using the Ottawa River for centuries.[22] Many missionaries would follow the early explorers and traders. The first maps of the area used the word Ottawa, derived from the Algonquin word adawe ("to trade", used in reference to the area's importance to First Nations traders), to name the river. Philemon Wright, a New Englander, created the first European settlement in the area on 7 March 1800 on the north side of the river, across from the present-day city of Ottawa in Hull.[23][24] He, with five other families and twenty-five labourers,[18] set about to create an agricultural community[25] called Wrightsville. Wright pioneered the Ottawa Valley timber trade (soon to be the area's most significant economic activity) by transporting timber by river from the Ottawa Valley to Quebec City.[26] Bytown, Ottawa's original name, was founded as a community in 1826 when hundreds of land speculators were attracted to the south side of the river when news spread that British authorities were immediately constructing the northerly end of the Rideau Canal military project at that location.[27][28] The following year, the town was named after British military engineer Colonel John By who was responsible for the entire Rideau Waterway construction project.

The canal's military purpose was to provide a secure route between Montreal and Kingston on Lake Ontario, bypassing a particularly vulnerable stretch of the St. Lawrence River bordering the state of New York that had left re-supply ships bound for southwestern Ontario easily exposed to enemy fire during the War of 1812.[29] Colonel By set up military barracks on the site of today's Parliament Hill. He also laid out the streets of the town and created two distinct neighbourhoods named "Upper Town" west of the canal and "Lower Town" east of the canal. Similar to its Upper Canada and Lower Canada namesakes, historically "Upper Town" was predominantly English speaking and Protestant whereas "Lower Town" was predominantly French, Irish and Catholic.[30] Bytown's population grew to 1,000 as the Rideau Canal was being completed in 1832.[31][32] Bytown encountered some impassioned and violent times in her early pioneer period that included Irish labour unrest that attributed to the Shiners' War from 1835 to 1845[33] and political dissension evident from the 1849 Stony Monday Riot.[34] In 1855 Bytown was renamed Ottawa and incorporated as a city.[35] William Pittman Lett was installed as the first city clerk guiding it through 36 years of development. [36]

On New Year's Eve 1857, Queen Victoria, as a symbolic and political gesture, was presented with the responsibility of selecting a location for the permanent capital of the Province of Canada.[37] In reality, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald had assigned this selection process to the Executive Branch of the Government, as previous attempts to arrive at a consensus had ended in deadlock.[38] The "Queen's choice" turned out to be the small frontier town of Ottawa for two main reasons:[39] Firstly, Ottawa's isolated location in a backcountry surrounded by dense forest far from the Canada–US border and situated on a cliff face would make it more defensible from attack.[40][41] Secondly, Ottawa was approximately midway between Toronto and Kingston (in Canada West) and Montreal and Quebec City (in Canada East). Additionally, despite Ottawa's regional isolation, it had seasonal water transportation access to Montreal over the Ottawa River and to Kingston via the Rideau Waterway. By 1854 it also had a modern all-season Bytown and Prescott Railway that carried passengers, lumber and supplies the 82-kilometres to Prescott on the Saint Lawrence River and beyond.[18][40] Ottawa's small size, it was thought, would make it less prone to rampaging politically motivated mobs, as had happened in the previous Canadian capitals.[42] The government already owned the land that would eventually become Parliament Hill which they thought would be an ideal location for the Parliament Buildings. Ottawa was the only settlement of any substantial size that was already directly on the border of French populated former Lower Canada and English populated former Upper Canada thus additionally making the selection an important political compromise.[43] Queen Victoria made her "Queen's choice" very quickly just before welcoming in the New Year.

Starting in the 1850s, entrepreneurs known as lumber barons began to build large sawmills, which became some of the largest mills in the world.[44] Rail lines built in 1854 connected Ottawa to areas south and to the transcontinental rail network via Hull and Lachute, Quebec in 1886.[45] The original Parliament buildings which included the Centre, East and West Blocks were constructed between 1859 and 1866 in the Gothic Revival style.[46] At the time, this was the largest North American construction project ever attempted and Public Works Canada and its architects were not initially well prepared. The Library of Parliament and Parliament Hill landscaping would not be completed until 1876.[47] By 1885 Ottawa was the only city in Canada whose downtown street lights were powered entirely by electricity.[48] In 1889 the Government developed and distributed 60 "water leases" (still currently in use) to mainly local industrialists which gave them permission to generate electricity and operate hydroelectric generators at Chaudière Falls.[49] Public transportation began in 1870 with a horsecar system,[50] overtaken in the 1890s by a vast electric streetcar system that lasted until 1959.

The Hull–Ottawa fire of 1900 destroyed two-thirds of Hull, including 40 percent of its residential buildings and most of its largest employers along the waterfront.[51] It also spread across the Ottawa River and destroyed about one fifth of Ottawa from the Lebreton Flats south to Booth Street and down to Dow's Lake.[52] On 1 June 1912 the Grand Trunk Railway opened both the Château Laurier hotel and its neighbouring downtown Union Station.[53][54] On 3 February 1916 the Centre Block of the Parliament buildings was destroyed by a fire.[55] The House of Commons and Senate was temporarily relocated to the then recently constructed Victoria Memorial Museum, now the Canadian Museum of Nature[56] until the completion of the new Centre Block in 1922, the centrepiece of which is a dominant Gothic revival styled structure known as the Peace Tower.[57] The current location of what is now Confederation Square was a former commercial district centrally located in a triangular area downtown surrounded by historically significant heritage buildings which includes the Parliament buildings. It was redeveloped as a ceremonial centre in 1938 as part of the City Beautiful Movement and became the site of the National War Memorial in 1939 and designated a National Historic Site in 1984.[58] A new Central Post Office (now the Privy Council of Canada) was constructed in 1939 beside the War Memorial because the original post office building on the proposed Confederation Square grounds had to be demolished.

Ottawa's former industrial appearance was vastly altered by the 1950 Greber Plan. Prime Minister Mackenzie King hired French architect-planner Jacques Greber to design an urban plan for managing development in the National Capital Region, to make it more esthetically pleasing and more befitting a location for Canada's political centre.[59][60] Greber's plan included the creation of the National Capital Greenbelt, the Parkway, the Queensway highway system, the relocation of downtown Union Station (now the Government Conference Centre) to the suburbs, the removal of the street car system, the decentralization of selected government offices, the relocation of industries and removal of substandard housing from the downtown and the creation of the Rideau Canal and Ottawa River pathways to name just a few of its recommendations.[59][61][62] In 1958 the National Capital Commission was established as a Crown Corporation from the passing of the National Capital Act to implement the Greber Plan recommendations-which it accomplished during the 1960s and 1970s.

In the previous 50 years, other commissions, plans and projects had failed to implement plans to improve the capital such as the 1899 Ottawa Improvement Commission (OIC), The Todd Plan in 1903, The Holt Report in 1915 and The Federal District Commission (FDC) established in 1927.[63] In 1958 a new City Hall opened on Green Island near Rideau falls where urban renewal had recently transformed this former industrial location into green space.[64] Until then, City Hall had temporarily been for 27 years (1931–1958) at the Transportation Building adjacent to Union Station and now part of the Rideau Centre. In 2001, Ottawa City Hall returned downtown to a relatively new building (1990) on 110 Laurier Avenue West, the prior home of the now defunct Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton. This new location was close to Ottawa's first (1849–1877) and second (1877–1931) City Halls. This new city hall complex also contained an adjacent 19th century restored heritage building formerly known as the Ottawa Normal School.[64]

From the 1960s until the 1980s, the National Capital Region experienced a building boom, [65] which was followed by large growth in the high-tech industry during the 1990s and 2000s.[66] Ottawa became one of Canada's largest high tech cities and was nicknamed Silicon Valley North. By the 1980s, Bell Northern Research (later Nortel) employed thousands, and large federally assisted research facilities such as the National Research Council contributed to an eventual technology boom. The early adopters led to offshoot companies such as Newbridge Networks, Mitel and Corel.

Ottawa's city limits had been increasing over the years, but it acquired the most territory on 1 January 2001, when it amalgamated all the municipalities of the Regional Municipality of Ottawa–Carleton into one single city.[67] Regional Chair Bob Chiarelli was elected as the new city's first mayor in the 2000 municipal election, defeating Gloucester mayor Claudette Cain. The city's growth led to strains on the public transit system and on road bridges. On 15 October 2001, a diesel-powered light rail transit (LRT) line was introduced on an experimental basis. Known today as the Trillium Line, it was dubbed the O-Train and connected downtown Ottawa to the southern suburbs via Carleton University. The decision to extend the O-Train, and to replace it with an electric light rail system was a major issue in the 2006 municipal elections where Chiarelli was defeated by businessman Larry O'Brien. After O'Brien's election transit plans were changed to establish a series of light rail stations from the east side of the city into downtown, and for using a tunnel through the downtown core. Jim Watson, the last mayor of Ottawa prior to amalgamation, was re-elected in the 2010 election.[68]

In October 2012, City Council approved the final Lansdowne Park plan, an agreement with the Ottawa Sports and Entertainment Group that saw a new stadium, increased green space, and housing and retail added to the site.[69][70] In December 2012, City Council voted unanimously to move forward with the Confederation Line, a 12.5 km (7.8 mi) light rail transit line, which was opened on 14 September 2019.[71]

Geography

Ottawa is on the south bank of the Ottawa River and contains the mouths of the Rideau River and Rideau Canal.[72] The older part of the city (including what remains of Bytown) is known as Lower Town, and occupies an area between the canal and the rivers. Across the canal to the west lies Centretown and Downtown Ottawa, which is the city's financial and commercial hub and home to the Parliament of Canada and numerous federal government department headquarters, notably the Privy Council Office. On 29 June 2007, the Rideau Canal, which stretches 202 km (126 mi) to Kingston, Fort Henry and four Martello towers in the Kingston area, was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[73]

Located within the major, yet mostly dormant Western Quebec Seismic Zone,[74] Ottawa is occasionally struck by earthquakes. Examples include the 2000 Kipawa earthquake,[75] a magnitude-4.5 earthquake on 24 February 2006,[76] the 2010 Central Canada earthquake,[77] and a magnitude-5.2 earthquake on 17 May 2013.[78]

Ottawa sits at the confluence of three major rivers: the Ottawa River, the Gatineau River and the Rideau River.[79] The Ottawa and Gatineau rivers were historically important in the logging and lumber industries and the Rideau as part of the Rideau Canal system for military, commercial and, subsequently, recreational purposes.[79] The Rideau Canal (Rideau Waterway) first opened in 1832 and is 202 km (126 mi) long. It connects the Saint Lawrence River on Lake Ontario at Kingston to the Ottawa River near Parliament Hill. It was able to bypass the unnavigable sections of the Cataraqui and Rideau rivers and various small lakes along the waterway due to flooding techniques and the construction of 47 water transport locks.The Rideau River got its name from early French explorers who thought the waterfalls at the point where the Rideau River empties into the Ottawa River resembled a "curtain". Hence they began naming the falls and river "rideau" which is the French equivalent of the English word for curtain.[80][22] During part of the winter season the Ottawa section of the canal forms the world's largest skating rink, thereby providing both a recreational venue and a 7.8 km (4.8 mi) transportation path to downtown for ice skaters (from Carleton University and Dow's Lake to the Rideau Centre and National Arts Centre).[81]

Across the Ottawa River, which forms the border between Ontario and Quebec, lies the city of Gatineau, itself the result of amalgamation of the former Quebec cities of Hull and Aylmer together with Gatineau.[82] Although formally and administratively separate cities in two separate provinces, Ottawa and Gatineau (along with a number of nearby municipalities) collectively constitute the National Capital Region, which is considered a single metropolitan area. One federal crown corporation, the National Capital Commission, or NCC, has significant land holdings in both cities, including sites of historical and touristic importance. The NCC, through its responsibility for planning and development of these lands, is an important contributor to both cities. Around the main urban area is an extensive greenbelt, administered by the NCC for conservation and leisure, and comprising mostly forest, farmland and marshland.[83]

Climate

Ottawa has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb)[84] with four distinct seasons and is between Zones 5a and 5b on the Canadian Plant Hardiness Scale.[85] The average July maximum temperature is 26.6 °C (80 °F). The average January minimum temperature is −14.4 °C (6.1 °F)

Summers are warm and humid in Ottawa. On average 11 days of the three summer months have temperatures exceeding 30 °C (86 °F), or 37 days if the humidex is considered. Average relative humidity averages 54% in the afternoon and 84% by morning.

Snow and ice are dominant during the winter season. On average Ottawa receives 224 cm (88 in) of snowfall annually but maintains an average 22 cm (9 in) of snowpack throughout the three winter months. An average 16 days of the three winter months experience temperatures below −20 °C (−4 °F), or 41 days if the wind chill is considered.[86]

Spring and fall are variable, prone to extremes in temperature and unpredictable swings in conditions. Hot days above 30 °C (86 °F) have occurred as early as April[87] or as late as October.[88][86] Annual precipitation averages around 940 mm (37 in).

Ottawa experiences about 2,130 hours of average sunshine annually (46% of possible). Winds in Ottawa are generally Westerlies averaging 13 km/h (8.1 mph) but tend to be slightly more dominant during the winter.[86]

The highest temperature ever recorded in Ottawa was 37.8 °C (100 °F) on 4 July 1913, 1 August 1917 and 11 August 1944.[86][89] The coldest temperature ever recorded was −38.9 °C (−38 °F) on 29 December 1933.[86]

| Climate data for Ottawa (Central Experimental Farm), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1872–present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

26.7 (80.1) |

31.2 (88.2) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.7 (98.1) |

37.8 (100.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

29.4 (84.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −5.8 (21.6) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

2.4 (36.3) |

11.4 (52.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

26.6 (79.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −10.2 (13.6) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

6.5 (43.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

19.9 (67.8) |

15.3 (59.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −14.4 (6.1) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

1.5 (34.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

15.7 (60.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

1.9 (35.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −37.8 (−36.0) |

−38.3 (−36.9) |

−36.7 (−34.1) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

−38.9 (−38.0) |

−38.9 (−38.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 62.9 (2.48) |

49.7 (1.96) |

57.5 (2.26) |

71.1 (2.80) |

86.6 (3.41) |

92.7 (3.65) |

84.4 (3.32) |

83.8 (3.30) |

92.7 (3.65) |

85.9 (3.38) |

82.7 (3.26) |

69.5 (2.74) |

919.5 (36.20) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 23.0 (0.91) |

17.9 (0.70) |

28.8 (1.13) |

63.2 (2.49) |

86.6 (3.41) |

92.7 (3.65) |

84.4 (3.32) |

83.8 (3.30) |

92.7 (3.65) |

83.1 (3.27) |

67.5 (2.66) |

31.9 (1.26) |

755.5 (29.74) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 44.3 (17.4) |

34.7 (13.7) |

29.1 (11.5) |

7.2 (2.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.9 (1.1) |

16.0 (6.3) |

41.3 (16.3) |

175.4 (69.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 16.0 | 11.7 | 11.5 | 13.2 | 14.5 | 12.4 | 11.6 | 11.2 | 12.9 | 14.9 | 15.2 | 15.6 | 160.7 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 3.7 | 3.5 | 5.5 | 11.5 | 14.4 | 12.4 | 11.6 | 11.2 | 12.9 | 14.6 | 11.6 | 5.5 | 118.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 14.1 | 9.7 | 7.4 | 2.7 | 0.08 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.81 | 5.1 | 12.2 | 52.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 99.3 | 131.3 | 167.1 | 189.8 | 229.8 | 254.2 | 279.0 | 249.3 | 177.6 | 139.4 | 84.3 | 82.6 | 2,083.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 35.0 | 44.9 | 45.3 | 46.9 | 49.9 | 54.3 | 58.9 | 57.1 | 47.1 | 41.0 | 29.4 | 30.3 | 45.0 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source: Environment Canada[89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97] and Weather Atlas[98] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Ottawa International Airport, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1938–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 13.9 | 15.1 | 30.0 | 35.1 | 41.8 | 44.0 | 47.2 | 47.0 | 42.5 | 33.9 | 26.1 | 18.4 | 47.2 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

27.4 (81.3) |

31.1 (88.0) |

35.8 (96.4) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

37.8 (100.0) |

35.1 (95.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

17.9 (64.2) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −5.8 (21.6) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

2.5 (36.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

12.7 (54.9) |

5.4 (41.7) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −10.3 (13.5) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

19.8 (67.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −14.8 (5.4) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

1.4 (34.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −35.6 (−32.1) |

−36.1 (−33.0) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−21.7 (−7.1) |

−34.4 (−29.9) |

−36.1 (−33.0) |

| Record low wind chill | −47.8 | −47.6 | −42.7 | −26.3 | −10.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −6.4 | −13.3 | −29.5 | −44.6 | −47.8 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 65.4 (2.57) |

54.3 (2.14) |

64.4 (2.54) |

74.5 (2.93) |

80.3 (3.16) |

92.8 (3.65) |

91.9 (3.62) |

85.5 (3.37) |

90.1 (3.55) |

86.1 (3.39) |

81.9 (3.22) |

76.4 (3.01) |

943.4 (37.14) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 25.0 (0.98) |

18.7 (0.74) |

31.1 (1.22) |

63.0 (2.48) |

80.1 (3.15) |

92.8 (3.65) |

91.9 (3.62) |

85.5 (3.37) |

90.1 (3.55) |

82.2 (3.24) |

64.5 (2.54) |

33.5 (1.32) |

758.2 (29.85) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 53.9 (21.2) |

43.3 (17.0) |

38.3 (15.1) |

11.3 (4.4) |

0.2 (0.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

3.7 (1.5) |

20.2 (8.0) |

52.5 (20.7) |

223.5 (88.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 16.6 | 13.1 | 12.7 | 12.4 | 13.4 | 13.2 | 11.9 | 11.0 | 12.3 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 17.4 | 163.6 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 4.4 | 3.9 | 6.7 | 10.9 | 13.4 | 13.2 | 11.9 | 11.0 | 12.3 | 13.7 | 11.0 | 6.0 | 118.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 16.1 | 12.1 | 8.8 | 3.5 | 0.17 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 6.8 | 14.7 | 63.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67.5 | 61.3 | 56.6 | 50.2 | 49.9 | 53.1 | 53.7 | 55.0 | 59.1 | 61.6 | 68.1 | 72.2 | 59.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 122.4 | 114.1 | 168.5 | 187.5 | 210.5 | 274.0 | 301.4 | 231.9 | 211.5 | 148.8 | 92.4 | 68.8 | 2,131.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 43.1 | 39.0 | 45.7 | 46.3 | 45.7 | 58.6 | 63.7 | 53.1 | 56.1 | 43.7 | 32.2 | 25.2 | 46.0 |

| Source: Environment Canada[86][99][100][101][102][103] | |||||||||||||

Neighbourhoods and outlying communities

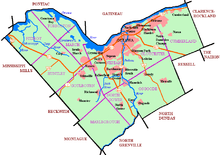

Ottawa is bounded on the east by the United Counties of Prescott and Russell; by Renfrew County and Lanark County in the west; on the south by the United Counties of Leeds and Grenville and the United Counties of Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry; and on the north by the Regional County Municipality of Les Collines-de-l'Outaouais and the City of Gatineau.[104] Modern Ottawa is made up of eleven historic townships, ten of which are from Carleton County and one from Russell.[105]

The city has a main urban area but many other urban, suburban and rural areas exist within the modern city's limits.[106] The main suburban area extends a considerable distance to the east, west and south of the centre,[106] and it includes the former cities of Gloucester, Nepean and Vanier, the former village of Rockcliffe Park (a high-income neighbourhood which is adjacent to the Prime Minister's official residence at 24 Sussex and the Governor General's residence), and the communities of Blackburn Hamlet and Orléans.[107] The Kanata suburban area includes the former village of Stittsville to the southwest.[107] Nepean is another major suburb which also includes Barrhaven.[107] The communities of Manotick and Riverside South are on the other side of the Rideau River, and Greely, southeast of Riverside South.[107] A number of rural communities (villages and hamlets) lie beyond the greenbelt but are administratively part of the Ottawa municipality.[106] Some of these communities are Burritts Rapids; Ashton; Fallowfield; Kars; Fitzroy Harbour; Munster; Carp; North Gower; Metcalfe; Constance Bay and Osgoode and Richmond.[107] Several towns are within the federally defined National Capital Region but outside the city of Ottawa municipal boundaries;[106] including the urban communities of Almonte, Carleton Place, Embrun, Kemptville, Rockland, and Russell.[107]

Demographics

| Historic Population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1901 | 101,102 | — |

| 1911 | 123,417 | +22.1% |

| 1921 | 152,868 | +23.9% |

| 1931 | 174,056 | +13.9% |

| 1941 | 206,367 | +18.6% |

| 1951 | 246,298 | +19.3% |

| 1956 | 287,244 | +16.6% |

| 1961 | 358,410 | +24.8% |

| 1966 | 413,695 | +15.4% |

| 1971 | 471,931 | +14.1% |

| 1976 | 520,533 | +10.3% |

| 1981 | 546,849 | +5.1% |

| 1986 | 606,639 | +10.9% |

| 1991 | 678,147 | +11.8% |

| 1996 | 721,136 | +6.3% |

| 2001[lower-alpha 2] | 774,072 | +7.3% |

| 2006 | 812,129 | +4.9% |

| 2011 | 883,391 | +8.8% |

| 2016 | 934,243 | +5.8% |

| Note: Population figures are extrapolated for current municipal boundaries Sources:[110][111][112][113][108][114][4] Chart format | ||

In 2016, the populations of the City of Ottawa and the Ottawa–Gatineau census metropolitan area (CMA) were 934,243 and 1,323,783 respectively. The city had a population density of 334.8/km2 (867/sq mi) in 2016, while the CMA had a population density of 195.6/km2 (507/sq mi). It is the second-largest city in Ontario, fourth-largest city in the country, and the fourth-largest CMA in the country.

Ottawa's median age of 40.1 is both below the provincial and national averages as of 2016. Youths under 15 years constituted 16.7% of the total population in 2016, while those of retirement age (65 years and older) made up 15.4%.

Over 20 percent of the city's population is foreign-born, with the most common non-Canadian countries of origin being the United Kingdom (8.8% of those foreign-born), China (8.0%), and Lebanon (4.8%). About 6.1% of residents are not Canadian citizens.[115]

Religion

Around 65% of Ottawa residents describe themselves as Christian as of 2011, with Catholics accounting for 38.5% of the population and members of Protestant churches 25%. Non-Christian religions are also very well established in Ottawa, the largest being Islam (6.7%), Hinduism (1.4%), Buddhism (1.3%), and Judaism (1.2%). Those with no religious affiliation represent 22.8%.[115]

Language

Bilingualism became official policy for the conduct of municipal business in 2002,[116] and 37.6% of the population can speak both languages as of 2016, making it the largest city in Canada with both English and French as co-official languages.[117] Those who identify their mother tongue as English constitute 62.4 percent, while those with French as their mother tongue make up 14.2 percent of the population. In terms of respondents' knowledge of one or both official languages, 59.9 percent and 1.5 percent of the population have knowledge of English only and French only, respectively; while 37.2 percent have a knowledge of both official languages. The overall Ottawa–Gatineau census metropolitan area (CMA) has a larger proportion of French speakers than Ottawa itself, since Gatineau is overwhelmingly French speaking. An additional 20.4 percent of the population list languages other than English and French as their mother tongue. These include Arabic (3.2%), Chinese (3.0%), Spanish (1.2%), Italian (1.1%), and many others.[115]

Ethnicity

As of 2016, approximately 69.1% of Ottawa's population was white, while 4.6% were aboriginal and 26.3% were visible minorities (higher than the national percentage of 22.3%). Below is a breakdown of the demographics.[118]

- 69.1% White

- 4.6% Aboriginal; 3.2% First Nations, 1.4% Métis, 0.2% Inuit

- 4.2% South Asian

- 5.1% East Asian; 4.5% Chinese, 0.3% Japanese, 0.3% Korean

- 6.6% Black

- 2.6% Southeast Asian; 1.3% Filipino

- 1.2% Latin American

- 4.5% Arab

- 0.3% West Asian

- 0.9% Multiracial; 2.3% including Métis

- 0.3% Other

Economy

As of 2015, the region of Ottawa-Gatineau has the sixth highest total household income of all Canadian metropolitan areas ($82,052).[119] The median household income after taxes is $73,745 which is higher than the national median of $61,348.[120] The unemployment rate in Ottawa in 2016 was 7.2%, lower than the national rate of 7.7%.[121] In 2019 Mercer ranks Ottawa with the third highest quality of living of any Canadian city, and 19th highest in the world.[122] It is also rated the second cleanest city in Canada, and third cleanest city in the world.[123]

Ottawa's primary employers are the Public Service of Canada and the high-tech industry, although tourism and healthcare also represent increasingly sizeable economic activities. The Federal government is the city's largest employer, employing over 110,000 individuals from the National Capital region.[124] The national headquarters for many federal departments are in Ottawa, particularly throughout Centretown and in the Terrasses de la Chaudière and Place du Portage complexes in Hull. The National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa is the main command centre for the Canadian Armed Forces and hosts the Department of National Defence.[125] The Ottawa area includes CFS Leitrim and the former CFB Rockcliffe. During the summer, the city hosts the Ceremonial Guard, which performs functions such as the Changing the Guard.[126] As the national capital of Canada, tourism is an important part of Ottawa's economy, particularly after the 150th anniversary of Canada which was centred in Ottawa. The lead-up to the festivities saw much investment in civic infrastructure, upgrades to tourist infrastructure and increases in national cultural attractions. The National Capital Region annually attracts an estimated 7.3 million tourists, who spend about 1.18 billion dollars.[127]

In addition to the economic activities that come with being the national capital, Ottawa is an important technology centre; in 2015, its 1800 companies employed approximately 63,400 people.[128] The concentration of companies in this industry earned the city the nickname of "Silicon Valley North".[66] Most of these companies specialize in telecommunications, software development and environmental technology. Large technology companies such as Nortel, Corel, Mitel, Cognos, Halogen Software, Shopify and JDS Uniphase were founded in the city.[129] Ottawa also has regional locations for Nokia, 3M, Adobe Systems, Bell Canada, IBM and Hewlett-Packard.[130] Many of the telecommunications and new technology are in the western part of the city (formerly Kanata). The "tech sector" was doing particularly well in 2015/2016.[131][132]

Another major employer is the health sector, which employs over 18,000 people.[133] Four active general hospitals are in the Ottawa area: Queensway Carleton Hospital, The Ottawa Hospital, Montfort Hospital, and Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Several specialized hospital facilities are also present, such as the University of Ottawa Heart Institute and the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre.[134] Nordion, i-Stat and the National Research Council of Canada and OHRI are part of the growing life science sector.[135][136] Business, finance, administration, and sales and service rank high among types of occupations.[114] Approximately ten percent of Ottawa's GDP is derived from finance, insurance and real estate whereas employment in goods-producing industries is only half the national average.[137] The City of Ottawa is the second largest employer[138][139] with over 15,000 employees.[139][140]

In 2006, Ottawa experienced an increase of 40,000 jobs over 2001 with a five-year average growth that was relatively slower than in the late 1990s.[141] While the number of employees in the federal government stagnated, the high-technology industry grew by 2.4%. The overall growth of jobs in Ottawa-Gatineau was 1.3% compared to the previous year, down to sixth place among Canada's largest cities. In 2016, the unemployment rate in Ottawa was 7.2%, which was below the national unemployment rate of 7.7%.[142] The economic downturn resulted in an increase in the unemployment rate between April 2008 and April 2009 from 4.7 to 6.3%. In the province, however, this rate increased over the same period from 6.4 to 9.1%.[143]

Culture

Traditionally the ByWard Market (in Lower Town), Parliament Hill and the Golden Triangle (both in Centretown – Downtown) have been the focal points of the cultural scenes in Ottawa.[144] Modern thoroughfares such as Wellington Street, Rideau Street, Sussex Drive, Elgin Street, Bank Street, Somerset Street, Preston Street, Richmond Road in Westboro, and Sparks Street are home to many boutiques, museums, theatres, galleries, landmarks and memorials in addition to eating establishments, cafes, bars and nightclubs.[145]

Ottawa hosts a variety of annual seasonal activities—such as Winterlude, the largest festival in Canada,[146] and Canada Day celebrations on Parliament Hill and surrounding downtown area, as well as Bluesfest, Canadian Tulip Festival, Ottawa Dragon Boat Festival, Ottawa International Jazz Festival, Fringe Festival and Folk Music Festival, that have grown to become some of the largest festivals of their kind in the world.[147][148] In 2010, Ottawa's Festival industry received the IFEA "World Festival and Event City Award" for the category of North American cities with a population between 500,000 and 1,000,000.[149]

As Canada's capital, Ottawa has played host to a number of significant cultural events in Canadian history, including the first visit of the reigning Canadian sovereign—King George VI, with his consort, Queen Elizabeth—to his parliament, on 19 May 1939.[150] VE Day was marked with a large celebration on 8 May 1945,[151] the first raising of the country's new national flag took place on 15 February 1965,[152] and the centennial of Confederation was celebrated on 1 July 1967.[153] Elizabeth II was in Ottawa on 17 April 1982, to issue a royal proclamation of the enactment of the Constitution Act.[154] In 1983, Prince Charles and Diana Princess of Wales came to Ottawa for a state dinner hosted by then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.[155] In 2011, Ottawa was selected as the first city to receive Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge during their tour of Canada.

Architecture

.jpg)

Influenced by government structures, much of the city's architecture tends to be formalistic and functional; however, the city is also marked by Romantic and Picturesque styles of architecture such as the Parliament Buildings' gothic revival architecture.[156] Ottawa's domestic architecture is dominated by single family homes, but also includes smaller numbers of semi-detached houses, rowhouses, and apartment buildings. Many domestic buildings are clad in brick, with small numbers covered in wood, stone, or siding of different materials; variations are common, depending on neighbourhoods and the age of dwellings within them.

The skyline has been controlled by building height restrictions originally implemented to keep Parliament Hill and the Peace Tower at 92.2 m (302 ft) visible from most parts of the city.[157] Today, several buildings are slightly taller than the Peace Tower, with the tallest on Albert Street being the 29-storey Place de Ville (Tower C) at 112 m (367 ft).[158] Federal buildings in the National Capital Region are managed by Public Works Canada, while most of the federal land in the region is managed by the National Capital Commission; its control of much undeveloped land gives the NCC a great deal of influence over the city's development.[159]

Museums and performing arts

Amongst the city's national museums and galleries is the National Gallery of Canada; designed by famous architect Moshe Safdie, it is a permanent home to the Maman sculpture.[160] The Canadian War Museum houses over 3.75 million artifacts and was moved to an expanded facility in 2005.[161] The Canadian Museum of Nature was built in 1905, and underwent a major renovation between 2004 and 2010.[162] Across the Ottawa river in Gatineau is the most visited museum in Canada, the Canadian Museum of History.[163] Designed by Canadian Aboriginal architect Douglas Cardinal, the curving-shaped complex, built at a cost of US$340 million, also houses the Canadian Children's Museum, the Canadian Postal Museum and a 3D IMAX theatre.[164]

The city is also home to the Canada Agriculture Museum, the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, the Canada Science and Technology Museum, Billings Estate Museum, Bytown Museum, Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, the Bank of Canada Museum, and the Portrait Gallery of Canada.[165]

The Ottawa Little Theatre, originally called the Ottawa Drama League at its inception in 1913, is the longest-running community theatre company in Ottawa.[166] Since 1969, Ottawa has been the home of the National Arts Centre, a major performing arts venue that houses four stages and is home to the National Arts Centre Orchestra, the Ottawa Symphony Orchestra and Opera Lyra Ottawa.[167] Established in 1975, the Great Canadian Theatre Company specializes in the production of Canadian plays at a local level.[168]

Historic and heritage sites

The Rideau Canal is the oldest continuously operated canal system in North America, and in 2007, it was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[169] In addition, 24 other National Historic Sites of Canada are in Ottawa, including: the Central Chambers, the Central Experimental Farm, the Château Laurier, Confederation Square, the former Ottawa Teachers' College, Office of the Prime Minister and Privy Council, Laurier House and the Parliament Buildings. Many other properties of cultural value have been designated as having "heritage elements" by the City of Ottawa under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act.[170]

Sports

Sport in Ottawa has a history dating back to the 19th century. Ottawa is home to six professional sports teams. The Ottawa Senators are a professional ice hockey team playing in the National Hockey League. The Senators play their home games at the Canadian Tire Centre.[171] The Ottawa Redblacks are a professional Canadian Football team playing in the Canadian Football League.[172] A professional soccer club, Atlético Ottawa, will play in the Canadian Premier League, following the dissolution of Ottawa Fury FC. A new rugby league team called the Ottawa Aces will play in the 2021 RFL League 1 competition.[173] The Redblacks, Atlético, and the Aces all play their home games at TD Place Stadium. The city is once again home to a professional basketball team, with the Ottawa Blackjacks beginning to play in the Canadian Elite Basketball League, out of the TD Place Arena.[174] Previously, Ottawa was home to the Ottawa SkyHawks basketball team, of the National Basketball League of Canada. The Ottawa Champions play professional baseball at Raymond Chabot Grant Thornton Park, most recently in the Can-Am League. They are currently league-less, however, following the merger of the Can-Am League and the Frontier League.

Several non-professional teams also play in Ottawa, including the Ottawa 67's junior ice hockey team.[175]

Collegiate teams in various sports compete in Canadian Interuniversity Sport. The Carleton Ravens are nationally ranked in basketball,[176] and the Ottawa Gee-Gees are nationally ranked in football and basketball. Algonquin College has also won numerous national championships. The city is home to an assortment of amateur organized team sports such as soccer, basketball, baseball, curling, rowing, hurling and horse racing.[177] Casual recreational activities, such as skating, cycling, hiking, sailing, golfing, skiing, and fishing/ice fishing are also popular.[177]

Current professional teams

| Professional Team | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ottawa Senators | National Hockey League (NHL) | Ice hockey | Canadian Tire Centre | 1990 | 0[nb 1] |

| Ottawa Redblacks | Canadian Football League (CFL) | Football | TD Place Stadium | 2010 | 1 |

| Ottawa Champions | None | Baseball | Raymond Chabot Grant Thornton Park | 2014 | 1 |

| Ottawa Blackjacks | Canadian Elite Basketball League (CEBL) | Basketball | TD Place Arena | 2019 | 0 |

| Atlético Ottawa | Canadian Premier League (CPL) | Soccer | TD Place Stadium | 2020 | 0 |

| Ottawa Aces | Rugby Football League (RFL) | Rugby League | TD Place Stadium | 2021* | 0 |

Government

The City of Ottawa is a single-tier municipality, meaning it is in itself a census division and has no county or regional municipality government above it.[178] As a single-tier municipality, Ottawa has responsibility for all municipal services, including fire, emergency medical services, police, parks, roads, sidewalks, public transit, drinking water, storm water, sanitary sewage and solid waste. Ottawa is governed by the 24-member Ottawa City Council consisting of 23 councillors each representing one ward and the mayor, currently Jim Watson,[179] elected in a citywide vote.

Along with being the capital of Canada, Ottawa is politically diverse in local politics. Most of the city has traditionally supported the Liberal Party.[180] Perhaps the safest areas for the Liberals are the ones dominated by Francophones, especially in Vanier and central Gloucester.[180] Central Ottawa is usually more left-leaning, and the New Democratic Party have won ridings there. Some of Ottawa's suburbs are swing areas, notably central Nepean and, despite its francophone population, Orléans.[180] The southern and western parts of the old city of Ottawa are generally moderate and swing to the Conservative Party.[180] The farther one goes outside the city centre like to Kanata and Barrhaven and rural areas, the voters tend to be increasingly conservative, both fiscally and socially.[180] This is especially true in the former Townships of West Carleton, Goulbourn, Rideau and Osgoode, which are more in line with the conservative areas in the surrounding counties.[180] However, not all rural areas support the Conservative Party. Rural parts of the former township of Cumberland, with a large number of Francophones, traditionally support the Liberal Party, though their support has recently weakened.[180]

At present, Ottawa is host to 130 embassies.[181] A further 49 countries accredit their embassies and missions in the United States to Canada.[181]

Transportation

Air

Ottawa is served by a number of airlines that fly into the Ottawa Macdonald–Cartier International Airport (IATA: YOW, ICAO: CYOW), as well as two main regional airports Gatineau-Ottawa Executive Airport, and the Ottawa/Carp Airport.[182]

Inter-city trains and buses

Ottawa station (IATA: XDS), is the main inter-city train station operated by Via Rail. It is located 4 km to the east of downtown in Eastway Gardens and serves Via Rail's Corridor Route. The city is also served by inter-city passenger rail service at Fallowfield station in Barrhaven.

Inter-city bus services operate out of Ottawa Central Station, 1.5 km south of downtown in Centretown and just north of Highway 417.[182]

Bus and rail

OC Transpo, a department of the city, operates the public transit system.[183] OC Transpo operates an integrated, multi-modal Rapid Transit system which includes:

- Line 1,[184] also known as the Confederation Line, which operates medium-capacity trains which travel under the city's downtown core,

- Line 2, also known as the Trillium Line, which is a north-south light rail transit corridor connecting the airport and south end of Ottawa to Line 1,[185] and

- a vast system of over 190 bus routes[186] served by a fleet of ordinary, articulated and double-decker buses along grade-separated, transit-only corridors with long distances between stops and full station amenities (including platforms, walkways, ticket booths, elevators and convenience stores), which connects Ottawa's suburbs to the inner city.

The Rapid bus service network operates all day, 7 days a week, reaching Kanata to the West, Barrhaven to the South-West, Orléans to the East, and South Keys to the South.[186] There are also several night bus routes that cover Line 1's downtown stations while it is shut off for the night, and backup service to downtown while the train is delayed.

Both OC Transpo and the Quebec-based Société de transport de l'Outaouais (STO) operate bus services between Ottawa and Gatineau.

OC Transpo also operates a door-to-door bus service for the differently-abled known as ParaTranspo.[183]

Construction was recently completed on the Confederation Line, a 12.5-kilometre (7.8 mi) light-rail transit line (LRT), which includes a 2.5-kilometre (1.6 mi) tunnel through the downtown area featuring three underground stations. The project broke ground in 2013, and opened in September 2019.[187][188] A further 30 km (19 mi) and 19 stations will be built by 2023, referred to as the Stage 2 plan.[189] There is a proposed LRT system that would link Ottawa with Gatineau.[190]

Freeways and roads

The city is served by two freeway corridors. The primary corridor is east-west and consists of provincial Highway 417 (designated as the Queensway) and Ottawa-Carleton Regional Road 174 (formerly Provincial Highway 17); a north-south corridor, Highway 416 (designated as Veterans' Memorial Highway), connects Ottawa to the rest of the 400-Series Highway network in Ontario at the 401. Highway 417 is also the Ottawa portion of the Trans-Canada Highway.

The city also has several scenic parkways (promenades), such as Colonel By Drive, Queen Elizabeth Driveway, the Sir John A. MacDonald Parkway, the Rockcliffe Parkway and the Aviation Parkway and has a freeway connection to Autoroute 5 and Autoroute 50, in Gatineau. In 2006, the National Capital Commission completed aesthetic enhancements to Confederation Boulevard, a ceremonial route of existing roads linking key attractions on both sides of the Ottawa River.[191]

Cycling and by foot

Numerous paved multi-use trails, mostly operated by the National Capital Commission, wind their way through much of the city, including along the Ottawa River, Rideau River, and Rideau Canal. These pathways are used for transportation, tourism, and recreation. Because many streets either have wide curb lanes or bicycle lanes, cycling is a popular mode of transportation throughout the year.[192] As of 31 December 2015, 900 km (560 mi) of cycling facilities are found in Ottawa, including 435 km (270 mi) of multi use pathways, 8 km (5.0 mi) of cycle tracks, 200 km (120 mi) of on-road bicycle lanes, and 257 km (160 mi) of paved shoulders.[193] 204 km (127 mi) of new cycling facilities were added between 2011 and 2014.[193] A downtown street that is restricted to pedestrians only, Sparks Street was turned into a pedestrian mall in 1966.[194] On Sundays (since 1960) and selected holidays and events additional avenues and streets are reserved for pedestrian and/or bicycle uses only.[195] In May 2011, The NCC introduced the Capital Bixi bicycle-sharing system.[196]

Education

Ottawa is known as one of the most educated cities in Canada, with over half the population having graduated from college and/or university.[197] Ottawa has the highest per capita concentration of engineers, scientists, and residents with PhDs in Canada.[198]

The city has two main public universities:

- Carleton University was founded in 1942 to meet the needs of returning World War II veterans and later became Ontario's first private, non-denominational college. Over time, Carleton would make the transition to the public university that it is today. In recent years, Carleton has become ranked highly among comprehensive universities in Canada.[199] The university's campus sits between Old Ottawa South and Dow's Lake.

- The University of Ottawa (originally named the "College of Bytown") was the first post-secondary institution established in the city in 1848. The university would eventually expand to become the largest English-French bilingual university in the world.[200] It is also a member of the U15, a group of highly respected research-intensive universities in Canada.[201] The university's campus is in the Sandy Hill neighbourhood, just adjacent to the city's downtown core.

Ottawa also has two main public colleges – Algonquin College and La Cité collégiale. It also has two Catholic universities – Dominican University College and Saint Paul University. Other colleges and universities in nearby areas (namely, the neighbouring city of Gatineau) include the University of Quebec en Outaouais, Cégep de l'Outaouais, and Heritage College.

Four main public school boards exist in Ottawa: English, English-Catholic, French, and French-Catholic. The English-language Ottawa-Carleton District School Board (OCDSB) is the largest board with 147 schools,[202] followed by the English-Catholic Ottawa Catholic School Board with 85 schools.[203] The two French-language boards are the French-Catholic Conseil des écoles catholiques du Centre-Est with 49 schools,[204] and the French Conseil des écoles publiques de l'Est de l'Ontario with 37 schools.[205] Ottawa also has numerous private schools which are not part of a board.

The Ottawa Public Library was created in 1906 as part of the famed Carnegie library system.[206] The library system had 2.3 million items as of 2008.[207]

Media

Three main daily local newspapers are printed in Ottawa: two English newspapers, the Ottawa Citizen established as the Bytown Packet in 1845 and the Ottawa Sun, and one French newspaper, Le Droit.[208] Multiple Canadian television broadcast networks and systems, and an extensive number of radio stations, broadcast in both English and French.

In addition to the market's local media services, Ottawa is home to several national media operations, including CPAC (Canada's national legislature broadcaster)[209] and the parliamentary bureau staff of virtually all of Canada's major newsgathering organizations in television, radio and print. The city is also home to the head office of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, although it is not the primary production location of most CBC radio or television programming.

Twin towns – sister cities

Ottawa is twinned with:

Notable people

See also

- Outline of Ottawa

- World national capitals

- List of Ottawa buildings

- Geography of Ottawa

Footnotes

- NHL Media Guide 2010. The original Senators (also known as the Ottawa Hockey Club) organization won eleven Stanley Cups, not the current organization founded in 1990. Neither the NHL or the Senators claim the current Senators to be a continuation of the original organization or franchise. The awards, statistics and championships of both eras are kept separate and the NHL franchise founding date of the current Senators is in 1991.

References

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc (2014). Britannica Student Encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-62513-172-0. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Art Montague (2008). "Ottawa Book of Everything" (PDF). MacIntyre Purcell Publishing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- Justin D. Edwards; Douglas Ivison (2005). Downtown Canada: Writing Canadian Cities. University of Toronto Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8020-8668-6. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2006 and 2011 censuses – 100% data". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and urban areas, 2006 and 2001 censuses – 100% data". Statistics Canada. 5 November 2008. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for census metropolitan areas, 2006 and 2011 censuses – 100% data". Statistics Canada. 5 November 2008. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Ottawa, [City Census subdivision], Ontario". Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Ottawa – Gatineau [Population centre], Ontario/Quebec". Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "City of Ottawa – Design C". Ottawa.ca. 20 May 2010. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- "Rapport au / Report to:". Ottawa.ca. 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- "National Capital Act (R. S. C., 1985, c. N-4)" (PDF). Department of Justice. 22 June 2011. p. 13 SCHEDULE (Section 2) 'DESCRIPTION OF NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION'. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- "Ottawa's population blooms to 1M". CBC. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Alan Rayburn (2001). Naming Canada: Stories About Canadian Place Names. University of Toronto Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-8020-8293-0. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Is Ottawa Canada's smartest city? Capital edges Toronto, Calgary in university-educated population". National Post. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- William J. Miller (2015). Geology: The Science of the Earth's Crust (Illustrations). P. F. Collier & Son Company. p. 37. GGKEY:Y3TD08H3RAT. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Pilon, Jean‐Luc. "Ancient History of the Lower Ottawa River Valley" (PDF). Ottawa River Heritage Designation Committee. Ontario Archaeology – Canadian Museum of Civilization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Taylor 1986, p. 11.

- Woods 1980, p. 5.

- Brault 1946, pp. 38, 39.

- Legget 1986, p. 36.

- Woods 1980, p. 7.

- Wetering 1997, p. 123.

- Lee 2006, p. 16.

- Lee 2006, p. 20.

- Wetering 1997, p. 11.

- Taylor 1986, p. 14.

- Woods 1980, p. 60.

- Legget 1986, pp. 22–24.

- Ottawa An illustrated History John H. Taylor Page 30 James Lorimer & Co

- "Timeline – Know your Ottawa!". Bytown Museum. 2010. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- Mika 1982, p. 114.

- "Shiners' Wars". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Martin 1997, p. 22.

- "Ottawa (ON)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- Bryan D. Cook (2015). Introducing William Pittman Lett: Ottawa's first city clerk and bard (1819–1892). B.D.C. Ottawa Consulting. p. 412. ISBN 978-1-771363-42-6.

- David DeRocco; John F. Chabot (2008). From Sea to Sea to Sea: A Newcomer's Guide to Canada. Full Blast Productions. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-9784738-4-6. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Taylor 1986, p. 56.

- "A Capital in the Making". National Capital Commission. Archived from the original on 8 January 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- Northey; Knight (1991). Choosing Canada's Capital: Conflict Resolution in a Parliamentary System. Issue 168 of Carleton Library Series, ISSN 0576-7784 (Revised ed.). McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-88629-148-8. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Saul Bernard Cohen (2003). Geopolitics of the world system. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8476-9907-0. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Mark Bourrie (1996). Canada's Parliament Buildings. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-88882-190-4. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Why Was Ottawa Chosen as the Federal Capital City?". Archived from the original on 2 February 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Woods 1980, p. 107.

- "Ottawa History – 1886–1890". Bytown Museum. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "The Parliament Buildings". parl.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 13 November 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Construction, 1859–1916". Archived from the original on 28 December 2014.

- Ottawa, An Illustrated History John H. Taylor Page 102 Jame Lorimer and Company Publishing

- "Chaudière Falls". Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- Wetering 1997, p. 28.

- "Report of the Ottawa and Hull Fire Relief Fund, 1900, Ottawa" (PDF). The Rolla L. Crain Co (Archive CD Books Canada). 31 December 1900. pp. 5–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- Wetering 1997, p. 57.

- "Ottawa's old train station: a 100-year timeline". ottawacitizen.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- Wetering 1997, p. 41.

- Hale 2011, p. 108.

- Dave Mullington (2005). Chain of office: biographical sketches of the early mayors of Ottawa (1847–1948). General Store Publishing House. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-897113-17-2. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Reader's Digest Association (Canada) (2004). The Canadian atlas: our nation, environment and people. Reader's Digest Association (Canada). p. 40. ISBN 978-1-55365-082-9. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "HistoricPlaces.ca". HistoricPlaces.ca. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- "The Gréber Report". ottawa.ca. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- "Planners Over Time". National Capital Commission. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- Donna L. Erickson (2006). MetroGreen: connecting open space in North American cities. Island Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-55963-843-2. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Keshen 2001, p. 360.

- "About the NCC". Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Taylor 1986, pp. 186–194.

- Hale 2011, p. 217.

- Larisa V. Shavinina (2004). Silicon Valley North: A High-tech Cluster of Innovation And Entrepreneurship. Elsevier. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-08-044457-4. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "City of Ottawa Act, 1999, Chapter 14, Schedule E". Service Ontario/Legislative Assembly of Ontario. 2010. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- "Watson wins Ottawa mayor's race". CBC News. 25 October 2010. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010.

- "Final Lansdowne deal passed by council". CBC News. 10 October 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- "Council gives final go ahead to Lansdowne project". Ottawa Citizen. 11 October 2012. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- "4 key dates as Ottawa's LRT becomes a reality". CBC.

- George Ripley; Charles Anderson Dana (1875). The American Cyclopaedia: a popular dictionary of general knowledge. Appleton. p. 733. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Rideau Canal". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- "Urban Geology of the National Capital Area – Bedrock topography". Gsc.nrcan.gc.ca. 14 April 2009. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- "Earthquakes (Ottawa)". Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- "Earthquake shakes Ottawa". Ottawa Citizen. 24 February 2006. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- "Magnitude 5.5 – Ontario-Quebec Border Region, Canada". USGS. 23 June 2010. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- "Earthquake shakes Ottawa". CTV. 17 May 2013. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- James R. Penn (2001). Rivers of the world: a social, geographical, and environmental sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-1-57607-042-0. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Samuel Edward Dawson (2007). The Saint Lawrence: Its Basin and Border-lands. Heritage Books. pp. 267–. ISBN 978-0-7884-2252-2. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Rideau Canal Skateway – National Capital Commission::". Canadian Heritage. 7 March 2011. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- Eran Razin; Patrick J. Smith (2006). Metropolitan governing: Canadian cases, comparative lessons. University of Alberta. p. 79. ISBN 978-965-493-285-1. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Jessica Brown; Nora J. Mitchell; Michael Beresford, eds. (2005). The protected landscape approach: linking nature, culture and community. IUCN—The World Conservation Union. p. 195. ISBN 978-2-8317-0797-6.

- "Climatic Regions [Köppen]". Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. June 2005. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- "phz1981-2010". Canada's Plant Hardiness Site. Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- "Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010 Station Data: Ottawa, Ontario". Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Canada, Environment. "Historical Climate Data – Environment Canada". climate.weather.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Canada, Environment. "Historical Climate Data – Environment Canada". climate.weather.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- "Ottawa CDA". Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for May 2010". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for January 1874". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for November 1875". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for August 1884". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for February 2011". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for March 2012". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for December 2012". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for February 2017". Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- d.o.o, Yu Media Group. "Ottawa, Canada – Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "1981 to 2010 Canadian Climate Normals". Environment Canada. 2 July 2013. Climate ID: 6106000. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- "Daily Data Report for October 2015". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Climate ID: 6106000. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for March 2012". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Climate ID: 6106000. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Daily Data Report for December 2012". Environment Canada. 22 September 2015. Climate ID: 6106000. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Electricity use to hit highest in years this week in Ontario". The Weather Network. 2 July 2018. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "ManyEyes Map Viewer Ottawa". Ottawa Neighbourhood Study – University of Ottawa. 2010. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- "Ottawa Rural Communities". The Rural Council of Ottawa-Carleton. 2002. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- "Neighborhoods of Ottawa". Google maps. 2011. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- "Ottawa Neighbourhoods". Ottawa Real Estate.ca. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- "2001 Community Profiles – Ottawa, Ontario (City)". Statistics Canada. 1 February 2007. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "2001 Community Profiles – Ottawa, Ontario (City/Dissolved)". Statistics Canada. 1 February 2007. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- "Population Change, City of Ottawa, 1901–2006". Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- Sado, E. V.; Vos, M. A. (1976). "Resources of construction aggregate in the regional municipality of Ottawa-Carleton" (PDF). Ontario Division of Mines. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- "Population, land area and population density : census division and subdivisions = Population, superficie et densité de la population: divisions et subdivisions de recensement". archive.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- "Search Censuses". Statistics Canada. 4 July 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Community Profiles from the 2006 Census – Ottawa, Ontario (City)". Statistics Canada. 6 December 2010. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "National Household Survey Profile, 2011". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- "Bilingualism Policy". City of Ottawa. 2011. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- Jenny Cheshire (1991). English around the world: sociolinguistic perspectives. Cambridge University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-521-39565-6. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (8 February 2017). "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Ottawa, City [Census subdivision], Ontario and Ontario [Province]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (8 February 2017). "Income Highlight Tables, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (8 February 2017). "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Ottawa, City [Census subdivision], Ontario and Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (8 February 2017). "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Ottawa, City [Census subdivision], Ontario and Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Quality of Living City Ranking | Mercer". mobilityexchange.mercer.com. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Eco-City Ranking". Mercer.com. 16 August 2010. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- "Employment – Ottawa | CMHC". Cmhc-schl.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- "Six-year consolidation of National Defence Headquarters given green light". Maclean's. Canadian Press. 13 December 2013. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- "About the Ceremonial Guard". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 16 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- "About Ottawa, Canada's Capital". City of Ottawa. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- "Tech jobs near all-time high as Region's jobless rate hits 6.8%". www.ottawacitizen.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Leonel Corona Treviño; Jérôme Doutriaux; Sarfraz A. Mian (2006). Building knowledge regions in North America: emerging technology innovation poles. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-84542-430-5. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Nick Novakowski; Rémy Tremblay (2007). Perspectives on Ottawa's High-tech Sector. Peter Lang. pp. 43–71. ISBN 978-90-5201-370-1. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Jones, Allison (8 February 2017). "Canada Census 2016: Ontario growth still slowing, but those who went West might soon be back". National Post. Toronto. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- "2006 City of Ottawa Health Status Report" (PDF). Ottawa Public Health. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- "City of Ottawa – 40. Major Employers in City of Ottawa, 2006". Ottawa.ca. 2008. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- "Finding healthcare". City of Ottawa. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- "City of Ottawa – 40. Major Employers in City of Ottawa, 2006". Ottawa.ca. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "OCRI | Life Sciences". Ocri.ca. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- "Ottawa's Vital Signs 2010" (PDF). Community Foundation of Ottawa. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- "CanaData – The Industrial Structure of Canada's Major City Labour Markets" (PDF). Reed Construction Data. November 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- "City of Ottawa – Compensation". ottawa.ca. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- "Ottawa's Vital Signs 2008" (PDF). Community Foundation of Ottawa. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- City of Ottawa. "2007 Annual development Report" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Census Profile, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- "Ottawa Labour Market Monitor, December 2010". Service Canada. 21 January 2011. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- Hale 2011, pp. 59–60.

- Hale 2011, pp. 61–68.

- Buckland, Jason (4 July 2010). "2. Winterlude – Biggest festivals in Canada". Money.ca.msn.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- "Ottawa Bluesfest". Ottawa-Information-Guide. 2011. Archived from the original on 4 July 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- "Tulips in the Capital". National Capital Commission. 2011. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- "2010 IFEA World Festival & Event City Award". International Festivals and Events Association. 16 September 2010. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- Arthur Bousfield; Garry Toffoli (1989). Royal spring: the royal tour of 1939 and the Queen Mother in Canada. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-55002-065-6. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- J. L. Granatstein (21 March 2005). The last good war: an illustrated history of Canada in the Second World War, 1939–1945. Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-1-55054-913-3. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Ruth Solski (2006). Big Book of Canadian Celebrations: Grades 4–6. S&S Learning Materials. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-55035-851-3. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Douglas Ord (2003). The National Gallery of Canada: ideas, art, architecture. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 369. ISBN 978-0-7735-2509-2. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Derek Hayes (2008). Canada: an illustrated history. Douglas & McIntyre. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-55365-259-5. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Princess Di across Canada". Globe and Mail. 22 June 2011. Archived from the original on 25 June 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- Shannon Ricketts; Leslie Maitland; Jacqueline Hucker (2004). A guide to Canadian architectural styles. University of Toronto Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-55111-546-7. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Keshen 2001, p. 455.

- "Place de Ville III". Skyscraper Source Media. 2011. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- "Mandate and Mission". The National Capital Commission. 10 October 2008. Archived from the original on 9 May 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- "National Gallery of Canada – Ottawa Tourism Official Site". Ottawatourism.ca. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- "WarMuseum.ca – About the Museum – Mission". Civilization.ca. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- Canada (19 January 2011). "Museum History | Canadian Museum of Nature". Nature.ca. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- "Canada's most visited museum celebrates 150th anniversary" (in French). Civilization.ca. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- "CBC Digital Archives – Douglas Cardinal's brand of native architecture". cbc.ca. 25 August 2009. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- "City of Ottawa – Museums and History". City of Ottawa. Archived from the original on 30 May 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- Hale 2011, p. 60.

- "NAC History". National Arts Centre. 17 March 1970. Archived from the original on 21 June 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- "Great Canadian Theatre Company". Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia. 13 January 2011. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2011.