The Economist

The Economist is an international weekly newspaper printed in magazine-format and published digitally that focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, and technology. Based in London, England, the newspaper is owned by The Economist Group, with core editorial offices in the United States, as well as across major cities in continential Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. In August 2015, Pearson sold its 50% stake in the newspaper to the Italian Agnelli family's investment company, Exor, for £469 million (US$531 million) and the paper re-acquired the remaining shares for £182 million ($206 million). In 2019, their average global print circulation was over 909,476, while combined with their digital presence, runs to over 1.6 million. Across their social media platforms, it reaches an audience of 35 million, as of 2016. The newspaper has a prominent focus on data journalism and analysis over original reporting, to both criticism and acclaim.

| |

.png) Cover of the 8 September 2001 issue[nb 1] | |

| Type | Weekly newspaper[1][2] |

|---|---|

| Format |

|

| Owner(s) | The Economist Group |

| Founder(s) | James Wilson |

| Editor | Zanny Minton Beddoes |

| Deputy editor | Tom Standage |

| Founded | September 1843 |

| Political alignment | Economic liberalism[3][4] Social liberalism[3][5] Radical centrism[6][7] |

| Headquarters | 1-11 John Adam Street Westminster, London, England |

| Circulation | 909,476 (print) 748,459 (digital) 1.6 million (combined) (as of July-December 2019[8]) |

| ISSN | 0013-0613 |

| Website | economist |

Founded in 1843, The Economist was first circulated by Scottish economist James Wilson to muster support for abolishing the British Corn Laws (1815–46), a system of import tariffs. Over time, the newspaper's coverage expanded further into political economy and eventually began running articles on current events, finance, commerce, and British politics. Throughout the mid- to late- 20th century, it greatly expanded its layout and format, adding opinion columns, special reports, political cartoons, reader letters, cover stories, art critique, book reviews, and technology features. The paper is often recognizable by its fire-engine-red nameplate and illustrated, topical covers. Individual articles are written anonymously, with no byline, in order for the paper to speak as one collective voice. The paper is supplemented by its sister lifestyle magazine, 1843, and a variety of podcasts, films, and books.

The editorial stance of The Economist primarily revolves around classical, social, and most notably, economic liberalism. Since its founding, it has supported radical centrism, favoring policies and governments that maintain centrist politics. The newspaper typically champions neoliberalism, particularly free markets, free trade, free immigration, deregulation, and globalisation. Despite a pronounced editorial stance, it is seen as having little reporting bias, rigorous fact checking and strict copy editing.[9][10] Its extensive use of word play, subscription prices, and typical depth of coverage has linked the paper with a high-income and educated readership, drawing both positive and negative connotations in the Western World.[11][12] In line with this, it claims to have influential readership of prominent business leaders and policy-makers.

History

The Economist was founded by the British businessman and banker James Wilson in 1843, to advance the repeal of the Corn Laws, a system of import tariffs.[13] A prospectus for the "newspaper" from 5 August 1843 enumerated thirteen areas of coverage that its editors wanted the publication to focus on:[14]

- Original leading articles, in which free-trade principles will be most rigidly applied to all the important questions of the day.

- Articles relating to some practical, commercial, agricultural, or foreign topic of passing interest, such as foreign treaties.

- An article on the elementary principles of political economy, applied to practical experience, covering the laws related to prices, wages, rent, exchange, revenue and taxes.

- Parliamentary reports, with particular focus on commerce, agriculture and free trade.

- Reports and accounts of popular movements advocating free trade.

- General news from the Court of St. James's, the Metropolis, the Provinces, Scotland, and Ireland.

- Commercial topics such as changes in fiscal regulations, the state and prospects of the markets, imports and exports, foreign news, the state of the manufacturing districts, notices of important new mechanical improvements, shipping news, the money market, and the progress of railways and public companies.

- Agricultural topics, including the application of geology and chemistry; notices of new and improved implements, state of crops, markets, prices, foreign markets and prices converted into English money; from time to time, in some detail, the plans pursued in Belgium, Switzerland, and other well-cultivated countries.

- Colonial and foreign topics, including trade, produce, political and fiscal changes, and other matters, including exposés on the evils of restriction and protection, and the advantages of free intercourse and trade.

- Law reports, confined chiefly to areas important to commerce, manufacturing, and agriculture.

- Books, confined chiefly, but not so exclusively, to commerce, manufacturing, and agriculture, and including all treatises on political economy, finance, or taxation.

- A commercial gazette, with prices and statistics of the week.

- Correspondence and inquiries from the newspaper's readers.

Wilson described it as taking part in "a severe contest between intelligence, which presses forward, and an unworthy, timid ignorance obstructing our progress", a phrase which still appears on its masthead as the publication's mission.[15] It has long been respected as "one of the most competent and subtle Western periodicals on public affairs".[16] It was cited by Karl Marx in his formulation of socialist theory, because Marx felt the publication epitomised the interests of the bourgeoisie.[17] He wrote: "the London Economist, the European organ of the aristocracy of finance, described most strikingly the attitude of this class."[18] In 1915, revolutionary Vladimir Lenin referred to The Economist as a "journal that speaks for British millionaires".[19] Additionally Lenin claimed that The Economist held a "bourgeois-pacifist" position and supported peace out of fear of revolution.[20]

In 1920, the paper's circulation rose to 6,170. In 1934, it underwent its first major redesign. The current fire engine red nameplate was created by Reynolds Stone in 1959.[21] In 1971, The Economist changed its broadsheet format into a magazine-style perfect-bound formatting.[22] In January 2012, The Economist launched a new weekly section devoted exclusively to China, the first new country section since the introduction of one on the United States in 1942.[23]

In 1991, James Fallows argued in The Washington Post that The Economist used editorial lines that contradicted the news stories they purported to highlight.[24] In 1999, Andrew Sullivan complained in The New Republic that it uses "marketing genius"[25] to make up for deficiencies in original reporting, resulting in "a kind of Reader's Digest"[26] for America's corporate elite.[26][27] The Guardian wrote that "its writers rarely see a political or economic problem that cannot be solved by the trusted three-card trick of privatisation, deregulation and liberalisation".[28]

In 2005, the Chicago Tribune named it the best English-language paper noting its strength in international reporting where it does not feel moved to "cover a faraway land only at a time of unmitigated disaster" and that it kept a wall between its reporting and its more conservative editorial policies.[29] In 2008, Jon Meacham, former editor of Newsweek and a self-described "fan", criticised The Economist's focus on analysis over original reporting.[30] In 2012, The Economist was accused of hacking into the computer of Justice Mohammed Nizamul Huq of the Bangladesh Supreme Court, leading to his resignation as the chairman of the International Crimes Tribunal.[31][32] In August 2015, Pearson sold its 50% stake in the newspaper to the Italian Agnelli family's investment company, Exor, for £469 million (US$531 million) and the paper re-acquired the remaining shares for £182 million ($206 million).[33][34]

Organisation

Shareholders

Pearson plc held a 50% shareholding via The Financial Times Limited until August 2015. At that time, Pearson sold their share in the Economist. The Agnelli family's Exor paid £287m to raise their stake from 4.7% to 43.4% while the Economist paid £182m for the balance of 5.04m shares which will be distributed to current shareholders.[35] Aside from the Agnelli family, smaller shareholders in the company include Cadbury, Rothschild (21%), Schroder, Layton and other family interests as well as a number of staff and former staff shareholders.[35][36] A board of trustees formally appoints the editor, who cannot be removed without its permission. The Economist Newspaper Limited is a wholly owned subsidiary of The Economist Group. Sir Evelyn Robert de Rothschild was Chairman of the company from 1972 to 1989.

Although The Economist has a global emphasis and scope, about two-thirds of the 75 staff journalists are based in the London borough of Westminster.[37] However, due to half of all subscribers originating in the United States, The Economist has core editorial offices and substantial operations in New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Washington D.C.[38][39]

Editor

The editor-in-chief, commonly known simply as "the Editor", of The Economist is charged with formulating the paper's editorial policies and overseeing corporate operations. Since its 1843 founding, the editors have been:

- James Wilson: 1843–1857

- Richard Holt Hutton: 1857–1861[40]

- Walter Bagehot: 1861–1877[41]

- Daniel Conner Lathbury: 1877–1881[42] (jointly)

- Robert Harry Inglis Palgrave: 1877–1883 (jointly)

- Edward Johnstone: 1883–1907[43]

- Francis Wrigley Hirst: 1907–1916

- Hartley Withers: 1916–1921

- Sir Walter Layton: 1922–1938

- Geoffrey Crowther: 1938–1956

- Donald Tyerman: 1956–1965

- Sir Alastair Burnet: 1965–1974

- Andrew Knight: 1974–1986

- Rupert Pennant-Rea: 1986–1993

- Bill Emmott: 1993–2006

- John Micklethwait: 2006–2014[44]

- Zanny Minton Beddoes: 2015–present[45]

Tone and voice

Though it has many individual columns, by tradition and current practice the newspaper ensures a uniform voice—aided by the anonymity of writers—throughout its pages,[46] as if most articles were written by a single author, which may be perceived to display dry, understated wit, and precise use of language.[47][48] The Economist's treatment of economics presumes a working familiarity with fundamental concepts of classical economics. For instance, it does not explain terms like invisible hand, macroeconomics, or demand curve, and may take just six or seven words to explain the theory of comparative advantage. Articles involving economics do not presume any formal training on the part of the reader and aim to be accessible to the educated layman. It usually does not translate short French (and German) quotes or phrases. It does describe the business or nature of even well-known entities, writing, for example, "Goldman Sachs, an investment bank".[49] The Economist is known for its extensive use of word play, including puns, allusions, and metaphors, as well as alliteration and assonance, especially in its headlines and captions. This can make it difficult to understand for those who are not native English speakers.[50]

The Economist has traditionally and historically persisted in referring to itself as a "newspaper",[51][52][53] rather than a "news magazine" due to its mostly cosmetic switch from broadsheet to perfect-binding format and its general focus on current affairs as opposed to specialist subjects.[54][55] It is legally classified as a newspaper in Britain[56] and is registered as "The Economist Newspaper Limited" under British corporate law.[57][58] In the United States, it is legally incorporated as "The Economist Newspaper Group" in New York.[59] Most databases and anthologies catalogue the weekly as a newspaper printed in magazine- or journal-format.[60] Furthermore The Economist often differentiates and contrasts itself as a newspaper against their sister lifestyle magazine, 1843, which does the same in turn. Editor Zanny Minton Bedoes clarified the distinction in 2016: "we call it a newspaper because it was founded in 1843, 173 years ago, [when] all [perfect-bound publications] were called newspapers."[61]

Editorial anonymity

Articles often take a definite editorial stance and almost never carry a byline. Not even the name of the editor is printed in the issue. It is a long-standing tradition that an editor's only signed article during their tenure is written on the occasion of their departure from the position. The author of a piece is named in certain circumstances: when notable persons are invited to contribute opinion pieces; when journalists of The Economist compile special reports (previously known as surveys); for the Year in Review special edition; and to highlight a potential conflict of interest over a book review. The names of The Economist editors and correspondents can be located on the media directory pages of the website.[62] Online blog pieces are signed with the initials of the writer and authors of print stories are allowed to note their authorship from their personal web sites.[63] "This approach is not without its faults (we have four staff members with the initials "J.P.", for example) but is the best compromise between total anonymity and full bylines, in our view", wrote one anonymous writer of The Economist.[64] There are three editorial and business areas in which the anonymous ethos of the weekly has contributed to strengthening its unique identity: collective and consistent voice, talent and newsroom management, and brand strength and clarity. [65]

The editors say this is necessary because "collective voice and personality matter more than the identities of individual journalists"[66] and reflects "a collaborative effort".[67] In most articles, authors refer to themselves as "your correspondent" or "this reviewer". The writers of the titled opinion columns tend to refer to themselves by the title (hence, a sentence in the "Lexington" column might read "Lexington was informed...").

American author and long-time reader Michael Lewis criticised the paper's editorial anonymity in 1991, labelling it a means to hide the youth and inexperience of those writing articles.[24][68] Although individual articles are written anonymously, there is no secrecy over who the writers are as they are listed on The Economist's website, which also provides summaries of their careers and academic qualifications.[69] Later, in 2009, Lewis included multiple Economist articles in his anthology about the 2008 financial crisis, Panic: The Story of Modern Financial Insanity.[70]

John Ralston Saul describes The Economist as a "...[newspaper] which hides the names of the journalists who write its articles in order to create the illusion that they dispense disinterested truth rather than opinion. This sales technique, reminiscent of pre-Reformation Catholicism, is not surprising in a publication named after the social science most given to wild guesses and imaginary facts presented in the guise of inevitability and exactitude. That it is the Bible of the corporate executive indicates to what extent received wisdom is the daily bread of a managerial civilization."[71]

Features

The Economist's primary focus is world events, politics and business, but it also runs regular sections on science and technology as well as books and the arts. Approximately every two weeks, the publication includes an in-depth special report (previously called surveys) on a given topic.[72] The five main categories are Countries and Regions, Business, Finance and Economics, Science, and Technology.

Since July 2007, there has also been a complete audio edition of the paper available 9 pm London time on Thursdays.[73] The audio version of The Economist is produced by the production company Talking Issues. The company records the full text of the newspaper in MP3 format, including the extra pages in the UK edition. The weekly 130 MB download is free for subscribers and available for a fee for non-subscribers.

The publication's writers adopt a tight style that seeks to include the maximum amount of information in a limited space.[74] David G. Bradley, publisher of The Atlantic, described the formula as "a consistent world view expressed, consistently, in tight and engaging prose".[75]

Letters

The Economist frequently receives letters from its readership in response to the previous week's edition. While it is known to feature letters from senior businesspeople, politicians, ambassadors, and spokespeople, the paper includes letters from typical readers as well. Well-written or witty responses from anyone are considered, and controversial issues frequently produce a torrent of letters. For example, the survey of corporate social responsibility, published January 2005, produced largely critical letters from Oxfam, the World Food Programme, United Nations Global Compact, the Chairman of BT Group, an ex-Director of Shell and the UK Institute of Directors.[76]

In an effort to foster diversity of thought, The Economist routinely publishes letters that openly criticize the paper's articles and stance. After The Economist ran a critique of Amnesty International and human rights in general in its issue dated 24 March 2007, its letters page ran a reply from Amnesty, as well as several other letters in support of the organisation, including one from the head of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights.[77] Rebuttals from officials within regimes such as the Singapore government are routinely printed, to comply with local right-of-reply laws without compromising editorial independence.[78]

Letters published in the paper are typically between 150 and 200 words long and had the now-discontinued salutation 'Sir' from 1843 to 2015. In the latter year, upon the appointment of Zanny Minton Beddoes, the first female editor, the salutation was dismissed; letters have since had no salutation. Previous to a change in procedure, all responses to online articles were usually published in "The Inbox". Comments can now be made directly under each article online.[79]

Columns

The publication runs several opinion columns whose names reflect their topic:

- Babbage (Technology): named for the inventor Charles Babbage, this column was established in March 2010 and focuses on various technology related issues.

- Bagehot (Britain): named for Walter Bagehot (/ˈbædʒət/), 19th-century British constitutional expert and early editor of The Economist. Since April 2017 it has been written by Adrian Wooldridge, who succeeded David Rennie.[80][81]

- Banyan (Asia): named for the banyan tree, this column was established in April 2009 and focuses on various issues across the Asian continent, and is written by Dominic Ziegler.

- Baobab (Africa & Middle East): named for the baobab tree, this column was established in July 2010 and focuses on various issues across the African continent.

- Bartleby (Work and management): named after the titular character of a Herman Melville short story, this column was established in May 2018. It is written by Philip Coggan.

- Bello (Latin America): named for Andrés Bello, a Venezuelan diplomat, poet, legislator and philosopher, who lived and worked in Chile.[82] The column was established in January 2014 and is written by Michael Reid.

- Buttonwood (Finance): named for the buttonwood tree where early Wall Street traders gathered. Until September 2006 this was available only as an on-line column, but it is now included in the print edition. Since 2018, it is written by John O'Sullivan, succeeding Philip Coggan.[83]

- Chaguan (China): named for Chaguan, the traditional Chinese Tea houses in Chengdu, this column was established on 13 September 2018.[84]

- Charlemagne (Europe): named for Charlemagne, Emperor of the Frankish Empire. It is written by Jeremy Cliffe[85] and earlier it was written by David Rennie (2007–2010) and by Anton La Guardia[86] (2010–2014).

- Erasmus (Religion and public policy) – named after the Dutch Christian humanist Erasmus.

- Game Theory (Sport): named after the science of predicting outcomes in a certain situation, this column focuses on "sports major and minor" and "the politics, economics, science and statistics of the games we play and watch".

- Johnson (language): named for Samuel Johnson, this column returned to the publication in 2016 and covers language. It is written by Robert Lane Greene.

- Lexington (United States): named for Lexington, Massachusetts, the site of the beginning of the American Revolutionary War. From June 2010 until May 2012 it was written by Peter David, until his death in a car accident.[87]

- Prospero (Books and arts): named after the character from William Shakespeare's play The Tempest, this column reviews books and focuses on arts-related issues.

- Schumpeter (Business): named for the economist Joseph Schumpeter, this column was established in September 2009 and is written by Patrick Foulis.

- Free Exchange (Economics): a general economics column, frequently based on academic research, replaced the column Economics Focus in January 2012

- Obituary (recent death): Since 1997 it has been written by Ann Wroe.[88]

The newspaper goes to press on Thursdays, between 6 pm and 7 pm GMT, and is available at newsagents in many countries the next day. It is printed at seven sites around the world.

TQ

Every three months, The Economist publishes a technology report called Technology Quarterly, or simply, TQ, a special section focusing on recent trends and developments in science and technology.[89][90] The feature is also known to intertwine "economic matters with a technology".[91] The TQ often carries a theme, such as quantum computing or cloud storage, and assembles an assortment of articles around the common subject.[92][93]

1843

In September 2007, The Economist newspaper launched a sister lifestyle magazine under the title Intelligent Life as a quarterly publication. At its inguaration it was billed as for "the arts, style, food, wine, cars, travel and anything else under the sun, as long as it’s interesting".[94] The magazine focuses on analyzing the "insights and predictions for the luxury landscape" across the world.[95] Approximately ten years later, in March 2016, the newspaper's parent company rebranded the lifestyle magazine as 1843, in honor of the paper's founding year. It has since remained at six issues per year and carries the motto "Stories of An Extraordinary World."[94] Unlike The Economist, the author's names appear next their articles in 1843.[96]

1843 features contributions from Economist journalists as well as writers around the world and photography commissioned for each issue. It is seen as a market competitor to The Wall Street Journal's WSJ. and the Financial Times' FT Magazine.[97] It has, since its March 2016 relaunch, been edited by Rosie Blau, a former correspondent for The Economist.[98]

The World Ahead

The paper also produces two annual reviews and predicative reports titled The World In [Year] and The World If [Year] as part of their The World Ahead franchise.[99] In both features, the newspaper publishes a review of the social, cultural, economic and political events that have shaped the year and will continue to influence the immediate future. The issue was described by the American think tank Brookings Institution as "The Economist's annual [150-page] exercise in forecasting."[100]

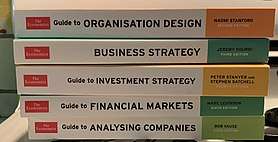

Books

In addition to publishing its main newspaper, lifestyle magazine, and special features, The Economist also produces books with topics greatly overlapping with that of its newspaper. The weekly also publishes a series of technical manuals (or guides) as an offshoot of its explanatory journalism. Some of these books serve as collections of articles and columns the paper produces.[101] Often columnists from the newspaper write technical manuals on their topic of expertise; for example, Philip Coggan, a finance correspondent, authored The Economist Guide to Hedge Funds (2011).[102]

Additionally, the paper publishes book reviews in every issue, with a large collective review in their year-end (holiday) issue – published as "The Economist's Books of the Year".[103] The paper has its own in-house stylebook rather than following an industry-wide writing style template.[104] All Economist writing and publications follow The Economist Style Guide, in various editions.[105][106]

Writing competitions

The Economist sponsors a wide-array of writing competitions and prices throughout the year for readers. In 1999, The Economist organised a global futurist writing competition, The World in 2050. Co-sponsored by Royal Dutch/Shell, the competition included a first prize of US$20,000 and publication in The Economist's annual flagship publication, The World In.[107] Over 3,000 entries from around the world were submitted via a website set up for the purpose and at various Royal Dutch Shell offices worldwide.[107] The judging panel included Bill Emmott, Esther Dyson, Sir Mark Moody-Stuart, and Matt Ridley.[108]

In the summer of 2019, they launched the Open Future writing competition with an inaugural youth essay-writing prompt about climate change.[109] During this competition the paper accepted a submission from an artificially-intelligent computer writing program.[110]

Data journalism

The presence of data journalism in The Economist can be traced to its founding year in 1843. Initially, the weekly published basic international trade figures and tables.[111][112] The paper first included a graphical model in 1847, with a bubble chart detailing precious metals, and its first non-epistolary chart was included in its 1854 issue, charting the spread of cholera.[111] This early adoption of data-based articles was estimated to be "a 100 years before the field’s modern emergence" by Data Journalism.com.[113] Its transition from broadsheet to magazine-style formatting led to the adoption of colored graphs, first in fire-engine-red during the 1980s and then to a thematic blue in 2001.[111] The Economist told their readers throughout the 2000s that the paper's editors had "developed a taste for data-driven stories."[111] Starting in the late-2000s, they began to publish more and more articles that centered solely on charts, some of which began to be published daily.[111] The daily charts are typically followed by a short, 300-word explanation. In September 2009, The Economist launched a Twitter account for their Data Team.[114]

In 2015, the weekly formed a dedicated team of 12 data analysts, designers, and journalists to head up their firm-wide data journalism efforts.[115] In order to ensure transparency in their data collection The Economist maintains a corporate GitHub account to publicly disclose all of their models and software.[116] In October 2018, they introduced their "Graphic Detail" feature in both their print and digital editions.[116] The Graphic Detail feature would go on to include mainly graphs, maps, and infographics.[117]

The Economist's Data Team won the 2020 Sigma Data Journalism Award for Best Young Journalists.[118] In 2015, they placed third for an infographic describing Israel's coalition networks in the year's Data Journalism Awards by the Global Editors Network.[119]

Indexes

Historically, the publication has also maintained a section of economic statistics, such as employment figures, economic growth, and interest rates. These statistical publications have been found to be seen as authoritative and decisive in British society.[120] The Economist also publishes a variety of rankings seeking to position business schools and undergraduate universities among each other, respectively. In 2015, they publish their first ranking of U.S. universities, focusing on comparable economical advantages. Their data for the rankings is sourced from the U.S. Department of Education and is calculated as a function of median earnings through regression analysis.[121] Among others, the most well-known data indexes the weekly publishes are:

- The Big Mac Index: a measure of the purchasing power of currencies, first published in 1986, using the price of the hamburger in different countries.[122][123] This is published twice a year, annually.

- Democracy Index: a measure of the state of democracy in the world, produced by the paper's Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU)

- The Glass Ceiling Index: a measure of female equality in the workplace.

- The Most Dangerous Cities Index: a measure of major cities by rates of homicide.

- Commodity-Price Index: a measure of commodities, such as gold and brent oil, as well as agricultural items

Opinions

The editorial stance of The Economist primarily revolves around classical, social, and most notably, economic liberalism. Since its founding, it has supported radical centrism, favoring policies and governments that maintain centrist politics. The newspaper typically champions neoliberalism, particularly free markets, free trade, free immigration, deregulation, and globalisation.[124] When the newspaper was founded, the term "economism" denoted what would today be termed "economic liberalism". The activist and journalist George Monbiot has described it as neo-liberal while occasionally accepting the propositions of Keynesian economics where deemed more "reasonable".[125] The weekly favours a carbon tax to fight global warming.[126] According to one former editor, Bill Emmott, "the Economist's philosophy has always been liberal, not conservative".[127]

Individual contributors take diverse views. The Economist favours the support, through central banks, of banks and other important corporations. This principle can, in a much more limited form, be traced back to Walter Bagehot, the third editor of The Economist, who argued that the Bank of England should support major banks that got into difficulties. Karl Marx deemed The Economist the "European organ" of "the aristocracy of finance".[128]

The newspaper has also supported liberal causes on social issues such as recognition of gay marriages,[129] legalisation of drugs,[130] criticises the US tax model,[131] and seems to support some government regulation on health issues, such as smoking in public,[132] as well as bans on spanking children.[133] The Economist consistently favours guest worker programmes, parental choice of school, and amnesties[134] and once published an "obituary" of God.[135] The Economist also has a long record of supporting gun control.[136]

The Economist has endorsed the Labour Party (in 2005), the Conservative Party (in 2010 and 2015),[137][138] and the Liberal Democrats (in 2017 and 2019) at general election time in Britain, and both Republican and Democratic candidates in the United States. Economist.com puts its stance this way:

What, besides free trade and free markets, does The Economist believe in? "It is to the Radicals that The Economist still likes to think of itself as belonging. The extreme centre is the paper's historical position". That is as true today as when Crowther [Geoffrey, Economist editor 1938–1956] said it in 1955. The Economist considers itself the enemy of privilege, pomposity and predictability. It has backed conservatives such as Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. It has supported the Americans in Vietnam. But it has also endorsed Harold Wilson and Bill Clinton, and espoused a variety of liberal causes: opposing capital punishment from its earliest days, while favouring penal reform and decolonisation, as well as—more recently—gun control and gay marriage.[21]

The Economist frequently accuses figures and countries of corruption or dishonesty. In recent years, for example, it criticised Paul Wolfowitz, World Bank president; Silvio Berlusconi, Italy's Prime Minister (who dubbed it The Ecommunist);[139] Laurent-Désiré Kabila, the late president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Robert Mugabe, the former head of government in Zimbabwe; and, recently, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, the president of Argentina.[140] The Economist also called for Bill Clinton's impeachment[141] and, after the emergence of the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse,[142] for Donald Rumsfeld's resignation. Though The Economist initially gave vigorous support for the US-led invasion of Iraq, it later called the operation "bungled from the start" and criticised the "almost criminal negligence" of the Bush Administration's handling of the war, while maintaining, in 2007, that pulling out in the short term would be irresponsible.[143] In an editorial marking its 175th anniversary, The Economist criticised adherents to liberalism for becoming too inclined to protect the political status quo rather than pursue reform.[144] The paper called on liberals to return to advocating for bold political, economic and social reforms: protecting free markets, land and tax reform in the tradition of Georgism, open immigration, a rethink of the social contract with more emphasis on education, and a revival of liberal internationalism.[144]

Circulation

Each of The Economist issue's official date range is from Saturday to the following Friday. The Economist posts each week's new content online at approximately 2100 Thursday evening UK time, ahead of the official publication date.[145] From July to December 2019, their average global print circulation was over 909,476, while combined with their digital presence, runs to over 1.6 million.[54] However, on a weekly average basis, the paper can reach up to 5.1 million readers, across their print and digital runs.[146] Across their social media platforms, it reaches an audience of 35 million, as of 2016.[147]

In 1877, the publication's circulation was 3,700, and in 1920 it had risen to 6,000. Circulation increased rapidly after 1945, reaching 100,000 by 1970.[21] Circulation is audited by the Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC). From around 30,000 in 1960 it has risen to near 1 million by 2000 and by 2016 to about 1.3 million.[148] Approximately half of all sales (54%) originate in the United States with sales in the United Kingdom making 14% of the total and continental Europe 19%.[38] Of its American readers, two out of three earn more than $100,000 a year. The Economist has sales, both by subscription and at newsagents, in over 200 countries.

The Economist once boasted about its limited circulation. In the early 1990s it used the slogan "The Economist – not read by millions of people". "Never in the history of journalism has so much been read for so long by so few," wrote Geoffrey Crowther, a former editor.[149]

Censorship

.jpg)

Sections of The Economist criticising authoritarian regimes are frequently removed from the paper by the authorities in those countries. The Economist regularly has difficulties with the ruling party of Singapore, the People's Action Party, which had successfully sued it, in a Singaporean court, for libel.[150]

Like many other publications, The Economist is subjected to censorship in India whenever it depicts a map of Kashmir. The maps are stamped by Indian Customs officials as being "neither correct, nor authentic". Issues are sometimes delayed, but not stopped or seized.[151]

On 15 June 2006, Iran banned the sale of The Economist when it published a map labelling the Persian Gulf simply as Gulf—a choice that derives its political significance from the Persian Gulf naming dispute.[152]

In a separate incident, the government of Zimbabwe went further and imprisoned The Economist's correspondent there, Andrew Meldrum. The government charged him with violating a statute on "publishing untruth" for writing that a woman was decapitated by supporters of the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front party. The decapitation claim was retracted[153] and allegedly fabricated by the woman's husband. The correspondent was later acquitted, only to receive a deportation order.

On 19 August 2013, The Economist disclosed that the Missouri Department of Corrections had censored its issue of 29 June 2013. According to the letter sent by the department, prisoners were not allowed to receive the issue because "1. it constitutes a threat to the security or discipline of the institution; 2. may facilitate or encourage criminal activity; or 3. may interfere with the rehabilitation of an offender".[154]

See also

- List of business newspapers

- List of newspapers in the United Kingdom

Notes

- The title and its design are references to the book No Logo (1999).

References

- "The Economist Is a Newspaper, Even Though It Doesn't Look Like One". Observer. 2 September 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Iber, Patrick (17 December 2019). "The World The Economist Made". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Zevin, Alexander (20 December 2019). "Liberalism at Large — how The Economist gets it right and spectacularly wrong". www.ft.com. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Mishra, Pankaj. "Liberalism According to The Economist". The New Yorker. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Mishra, Pankaj. "Liberalism According to The Economist". The New Yorker. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Is The Economist left- or right-wing?". The Economist. 2 September 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "True Progressivism". The Economist. 13 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- "The Economist - Data - ABC | Audit Bureau of Circulations". www.abc.org.uk.

- Pressman, Matt (20 April 2009). "Why Time and Newsweek Will Never Be The Economist". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Leadership, The Berlin School Of Creative (1 February 2017). "10 Journalism Brands Where You Find Real Facts Rather Than Alternative Facts". Forbes. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Burnell, Ian (31 January 2019). "Why The Economist swapped its famous elitist marketing for emotional messaging". The Drum. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Peters, Jeremy W. (8 August 2010). "The Economist Tends Its Sophisticate Garden". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- From the Corn Laws to Your Mailbox, The MIT Press Log, 30 January 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- "Prospectus". The Economist. 5 August 1843. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- "Opinion: leaders and letters to the Editor". The Economist. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Nathan Leites (1952). "The Politburo Through Western Eyes". World Politics. 4 (2): 159–185. doi:10.2307/2009044. JSTOR 2009044.(subscription required)

- McLellan, David (1 December 1973). Karl Marx: His Life and Thought. Springer. ISBN 9781349155149.

- Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, VI (1852)

- Zevin, Alex (12 November 2019). Liberalism at Large: The World According to the Economist. Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-78168-624-9.

- "Bourgeois Philanthropists and Revolutionary Social-Democracy".

- "About us". The Economist. 18 November 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- Economist, The (6 April 2017). "Why does The Economist call itself a newspaper?". Medium. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "The Economist Launches New China Section". Asian Media Journal. Archived from the original on 1 February 2012.

- "The Economics of the Colonial Cringe: Pseudonomics and the Sneer on the Face of The Economist". The Washington Post. 16 October 1991. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- "London Fog". Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- "Not so groovy". The New Republic. London. 14 June 1999. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- Finkel, Rebecca (July 1999). "Nasty barbs fly between New Republic and Economist". Media Life. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- Stern, Stefan (21 August 2005). "Economist thrives on female intuition". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- Entertainment: 50 Best Magazines, Chicago Tribune, 15 June 2006.

- "Jon Meacham Wants Newsweek to Be More Like Hayes' Esquire". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- "Discrepancy in Dhaka". The Economist. 8 December 2012.

- "Economist accused of hacking ICT judge's computer". The Washington Post. 9 December 2012.

- "Pearson Unloads $731 Million Stake in the Economist". HuffPost. 12 August 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- West, Karl (15 August 2015). "The Economist becomes a family affair". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

Pearson, the education and publishing giant that has held a non-controlling 50% stake since 1928, is selling the holding for £469m. The deal will make Italy's Agnelli family, founders of the Fiat car empire, the largest shareholder

- West, Karl (15 August 2015). "The Economist becomes a family affair". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

Pearson, the education and publishing giant that has held a non-controlling 50% stake since 1928, is selling the holding for £469m. The deal will make Italy's Agnelli family, founders of the Fiat car empire, the largest shareholder

- "Agnellis, Rothschilds close in on Economist". POLITICO. 11 August 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- "So what's the secret of 'The Economist'?". The Independent. London. 26 February 2006. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- "'Economist' Magazine Wins American Readers". NPR. 8 March 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- "Locations of The Economist in the United States". www.economistgroup.com. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- The Concise Dictionary of National Biography makes him assistant editor 1858–1860

- He was Wilson's son-in-law

- A journalist and biographer

- Discuz! Team and Comsenz UI Team. "economist150周年(1993) – 经济学人资料库 – ECO中文网 – Powered by Discuz! Archiver". Archived from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Sweney, Mark (9 December 2014). "John Micklethwait leaving the Economist to join Bloomberg News". The Guardian.

- "Zanny Minton Beddoes". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Style Guide". The Economist. 27 September 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- "The Economist – Tone". The Economist. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- "Johnson". The Economist. Archived from the original on 19 December 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- "A bank by any other name". The Economist. 21 February 2008. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- Richard J. Alexander, "Article Headlines in The Economist: An Analysis of Puns, Allusions and Metaphors", Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 11:2:159-177 (1986) JSTOR 43023400

- Iber, Patrick (17 December 2019). "The World The Economist Made". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Somaiya, Ravi (4 August 2015). "Up for Sale, The Economist Is Unlikely to Alter Its Voice". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- The Economist: A Weekly Financial, Commercial, and Real-estate Newspaper. Economist Publishing Company. 1899.

- "Seriously popular: The Economist now claims to reach 5.3m readers a week in print and online". pressgazette.co.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- "The Economist Is a Newspaper, Even Though It Doesn't Look Like One". Observer. 2 September 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Ms A Pannelay v The Economist Newspaper Ltd: 3200782/2018". GOV.UK. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Ownership | Economist Group". www.economistgroup.com. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- The Economist. Economist Newspaper Limited. 1884.

- "Economist Newspaper Group Inc". Bloomberg. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "The economist". The economist. 1843. ISSN 0013-0613. OCLC 1081684.

- TV, Kidspiration (20 September 2016). "Meeting a Powerful Journalist | Zanny Minton Beddoes". YouTube. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "Media directory". The Economist. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Why The Economist has no bylines". Andreaskluth.org. 20 November 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Why are The Economist's writers anonymous?". The Economist. 4 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- Arrese, Ángel (March 2020). """It's Anonymous. It's The Economist". The Journalistic and Business Value of Anonymity"". Journalism Practice. doi:10.1080/17512786.2020.1735489.

- "The Economist – About us". The Economist. 18 November 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- "Economist Editor Micklethwait brings his global perspective to the Twin Cities". MinnPost.com. 29 April 2008. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- High, Peter. "Bestselling Author Michael Lewis Has It All Figured Out". Forbes. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Media directory". The Economist. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- Lewis, Michael M. (2009). Panic: The Story of Modern Financial Insanity. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06514-5.

- The Doubter's Companion: A Dictionary of Aggressive Common Sense. ASIN 0743236602.

- "Special reports". The Economist. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- Allen, Katie (11 July 2007). "Economist launches audio magazine". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- "The Economist style guide". The Economist. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- "A Seven Year Ambition". mediabistro.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008.

- "Compilation: Full text of responses to Economist survey on Corporate Social Responsibility (January–February 2005)". Business & Human Rights. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- "Letters: On Amnesty International and human rights, Iraq, tax breaks 4 April 2007". The Economist. 4 April 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- Francis T. Seow (1998). The Media Enthralled: Singapore Revisited. Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. 171–175. ISBN 9781555877798. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Latest blog posts". The Economist. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- "Britain's cheering gloom". The Economist. 30 June 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- "Charlemagne moves town". The Economist. 30 June 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- "The Bello column: Choosing a Name". The Economist. 30 January 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "John O'Sullivan". Economist. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "The Economist's new China column: Chaguan". The Economist website. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- People: Jeremy Cliffe Archived 15 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine – Economist Media Directory. Retrieved 14/1/19

- "Media Directory". The Economist. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- "Lexington: Peter David". The Economist website. 11 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- "An Interview with Ann Wroe, Obituaries Writer for The Economist". 6 June 2014. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- "Technology Quarterly". The Economist. 1 June 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- Thanopoulos, John (15 April 2014). Global Business and Corporate Governance: Environment, Structure, and Challenges. Business Expert Press. ISBN 978-1-60649-865-1.

- "The Economist. Technology Quarterly | UOC Library". biblioteca.uoc.edu. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "The Economist Technology Quarterly: Quantum Technologies and Their Applications". 1QBit. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Cawsey, T. F.; Deszca, Gene (2007). Toolkit for Organizational Change. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-4106-8.

- "FAQs". 1843. The Economist Newspaper Limited. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- "An Evening at The Economist & 1843". Walpole. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Conti, Samantha; Conti, Samantha (8 March 2016). "1843, The Economist Unveils a Relaunched, Rebranded Lifestyle Title". WWD. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Blunden, Nick (November 2015). "Welcome to 1843" (PDF). The Economist Group.

- Atkins, Olivia (13 March 2019). "The Economist relaunches its lifestyle magazine, 1843". The Drum. Carnyx Group Limited. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- "'The Economist' Releases 'The World In 2020' Issue, Magazine's Circ Expected To Hit 1 Million". www.mediapost.com. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Gill, Indermit (10 April 2020). "The World in 2020, as forecast by The Economist". Brookings. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Woe, Ann. The Economist Book of Obituaries. ISBN 978-1-57660-326-0.

- Coggan, Philip (30 June 2011). The Economist Guide to Hedge Funds. Profile. ISBN 978-1-84765-037-5.

- "The Economist's books of the year | Department of History". history.stanford.edu. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Stevenson, Cambell (8 January 2006). "Observer review: The Economist Syle Guide". the Guardian. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Chibber, Kabir (14 December 2014). "We compared The Economist's very British style guide to Bloomberg's, and it was quite amusing". Quartz. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Joshi, Yateendra (19 March 2014). "The Economist Style Guide, 10th edition". Editage Insights. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "What is your vision of the future?". New Straights Times. 22 April 2000.

- "Getting better all the time". The Economist. 13 May 2010.

- "Climate Change Essay Contest offered by The Economist". School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Piper, Kelsey (4 October 2019). "The Economist's essay contest featured an AI submission. Here's what the judges thought". Vox. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Selby-Boothroyd, Alex (18 October 2018). "Data journalism at The Economist gets a home of its own in print". Medium. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "AMA with The Economist's data team - Newsletter". DataJournalism.com. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "AMA with The Economist's data team - Newsletter". DataJournalism.com. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "The Economist Data Team (@ECONdailycharts) | Twitter". twitter.com. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "How The Economist uses its 12-person data journalism team to drive subscriptions". What’s New in Publishing | Digital Publishing News. 4 May 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Economist, The (22 October 2018). "Turning a page: The Economist's data journalism gets its own place in print". Medium. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "The Economist's print edition launches a dedicated data journalism page for better visual storytelling | Media news". www.journalism.co.uk. 23 October 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Sigma Data Journalism Awards". DataJournalism.com. 5 February 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

G. Elliott Morris, Organisation: The Economist (United States)

- "DJA Newsletter". GEN. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

To explain something complex doesn’t always require an interactive graphic. This look by The Economist’s team illustrates the complexities of Israeli politics in one long chart where it pays to scroll — and which would work equally well in print as online.

- Great expectations—the social sciences in Great Britain. Commission on the Social Sciences. 2004. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7658-0849-3.

- "The Economist "The value of university: Our first-ever college rankings"". The Economist. 29 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- Paul R. Krugman, Maurice Obstfeld (2009). International Economics. Pearson Education. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-321-55398-0.

- "On the Hamburger Standard". The Economist. 6–12 September 1986.

- "Globalisation: The redistribution of hope". The Economist. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- George Monbiot (11 January 2005). "George Monbiot, Punitive – and it works". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Buttonwood: Let them heat coke". The Economist. 14 June 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Emmot, Bill (8 December 2000). "Time for a referendum on the monarchy". Comment. London. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- Marx, Karl (1852). The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.

- Let them wed, cover article on 4 January 1996

- How to stop the drug wars, cover article on 7 March 2009. The publication calls legalisation "the least bad solution".

- "Tax reform in America: A simple bare necessity". The Economist. 4 February 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Smoking and public health: Breathe easy". The Economist. 10 June 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Spare The Rod, Say Some", The Economist, 31 May 2008.

- Sense, not Sensenbrenner, The Economist, 30 March 2006

- "Obituary: God". The Economist. 23 December 1999.

- "Lexington: Reflections on Virginia Tech". The Economist. 8 April 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- "The Economist backs the Conservatives", The Guardian (PA report), 29 April 2010.

- "Who should govern Britain?". The Economist. 2 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Report of Rome anti-war demo on Saturday 24th with photos". Independent Media Center. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- "Cristina in the land of make believe". The Economist. 1 May 2008.

- "Just go". The Economist. 17 September 1998. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "Resign Rumsfeld". The Economist. 6 May 2004. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- "Mugged by reality". The Economist. 22 March 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2007.

- "The Economist at 175". The Economist. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "The Economist launches on Android". The Economist. 2 August 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Seriously popular: The Economist now claims to reach 5.3m readers a week in print and online". pressgazette.co.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- Ponsford, Dominic (8 March 2016). "The Economist boasts 1.5m magazine circulation and 36m social media followers". Press Gazette. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Lucinda Southern (17 February 2016). "The Economist Plans to Double Circulation Profits in 5 Years". Digiday. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- Moseley, Ray. ""Economist" aspires to influence, and many say it does" (pay archive). The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- "Inconvenient truths in Singapore". Asia Times. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- "Censorship in India". The Economist. 7 December 2010.

- "Iran bans The Economist over map". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- "Guardian and RFI correspondent risks two years in jail". Reporters Without Borders. Archived from the original on 4 April 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "The Economist in prison: About that missing issue". The Economist. 19 August 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

Further reading

- Arrese, Angel (1995), La identidad de The Economist, Pamplona: Eunsa. ISBN 9788431313739. (preview)

- Edwards, Ruth Dudley (1993), The Pursuit of Reason: The Economist 1843–1993, London: Hamish Hamilton, ISBN 0-241-12939-7

- Tungate, Mark (2004). "The Economist". Media Monoliths. Kogan Page Publishers. pp. 194–206. ISBN 978-0-7494-4108-1.

External links

- Official website

- The Economist at the HathiTrust Digital Library