National Museum of Natural History, France

The French National Museum of Natural History, known in French as the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle (MNHN; French: [myzeœ̃ nasjɔnal distwar natyʁɛl]), is the natural history museum of France and a grand établissement of Sorbonne Universities. The main museum is located in Paris, on the left bank of the Seine. It was established in 1635 by King Louis XIII as the royal garden of medicinal plants, and in 1793, after the Revolution, it was reorganized in its present form and under its present title. As of 2017, the museum has 14 sites throughout France, including the original location at the Jardin des Plantes, which remains one of the seven departments of MNHN.

Muséum national d'histoire naturelle | |

Gallery of Evolution in the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, France | |

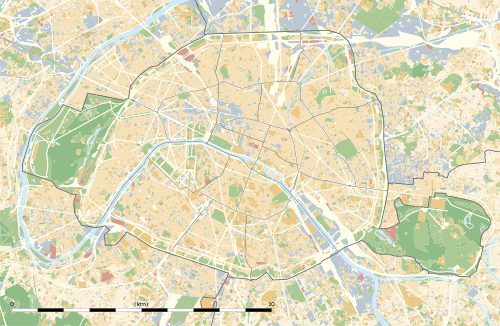

Location within Paris | |

| Established | June 10, 1793 |

|---|---|

| Location | 57 Rue Cuvier, Paris, France |

| Coordinates | 48.8422°N 2.3564°E |

| Type | natural history museum |

| Collection size | 68 million specimens[1] |

| Visitors | 1.9 million per year |

| Director | Bruno David |

| Public transit access | Jussieu Place Monge Austerlitz |

| Website | www |

| Muséum national d'histoire naturelle network | |

| |

History

The museum was formally founded on 10 June 1793, during the French Revolution. Its origins lie, however, in the Jardin royal des plantes médicinales (royal garden of medicinal plants) created by King Louis XIII in 1635, which was directed and run by the royal physicians. The royal proclamation of the boy-king Louis XV on 31 March 1718, however, removed the purely medical function, enabling the garden—which became known simply as the Jardin du Roi (King's garden)—to focus on natural history.

For much of the 18th century (1739–1788), the garden was under the direction of Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, one of the leading naturalists of the Enlightenment, bringing international fame and prestige to the establishment. The royal institution remarkably survived the French Revolution by being reorganized in 1793 as a republican Muséum national d'histoire naturelle with twelve professorships of equal rank. Some of its early professors included eminent comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier and evolutionary pioneers Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. The museum's aims were to instruct the public, put together collections and conduct scientific research. It continued to flourish during the 19th century, and, particularly under the direction of chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, became a rival to the University of Paris in scientific research. For example, during the period that Henri Becquerel held the chair for Applied Physics at the Muséum (1892–1908) he discovered the radiation properties of uranium. (Four generations of Becquerels held this chairmanship, from 1838 to 1948.)[2]

A decree of 12 December 1891 ended this phase, returning the museum to an emphasis on natural history. After receiving financial autonomy in 1907, it began a new phase of growth, opening facilities throughout France during the interwar years. In recent decades, it has directed its research and education efforts at the effects on the environment of human exploitation. In French public administration, the Muséum is classed as a grand établissement of higher education.

Origin of the collections

In the 19th century Argentine naturalist Francisco Javier Muñiz developed a collection that he intended to be used to create a natural history museum. The artifacts were sent (donated or possibly donated by force) to Juan Manuel de Rosas,[3][4] the dictator of the Argentine Federation, whose support was required to establish a museum.[5] Rosas, in an attempt to build alliances overseas, sent collected fossils to Jean Henri Dupotet, Rear Admiral of the French Navy. Dupotet then sent them to Paris.[5] In France, the Muñiz collection ended up in the National Museum of Natural History where they were studied by Paul Gervais.[4]

In 1762 Jean Baptiste Christophore Fusée Aublet was sent to Cayenne in French Guiana, where he assembled a vast herbarium which allowed him to prepare his Histoire des plantes de la Guiane françoise, published in 1775 and including almost 400 copperplate engravings. When Fusée Aublet died at Paris in 1778, he left his herbarium to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, though the latter possessed it for only two months before he too died. It was eventually acquired by the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in 1953.

During the French Revolution the Museum expanded its collection substantially by claiming objects from the cabinets of the aristocracy and from other institutions, such as the Royal Academy of Sciences and the École Royale Vétérinaire d'Alfort.[6]

Mission and organization

The museum has as its mission both research (fundamental and applied) and public diffusion of knowledge. It is organized into seven research and three diffusion departments.[7]

The research departments are:

- Classification and Evolution

- Regulation, Development, and Molecular Diversity

- Aquatic Environments and Populations

- Ecology and Biodiversity Management

- History of Earth

- Men, Nature, and Societies, and

- Prehistory

The diffusion departments are:

- The Galleries of the Jardin des Plantes

- Botanical Parks and Zoos, and

- The Museum of Man (Musée de l'Homme)

The museum also developed higher education, and now delivers a master's degree.[8]

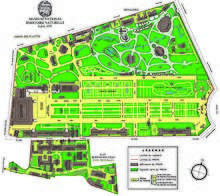

Location and branches

The museum comprises fourteen sites[9] throughout France with four in Paris, including the original location at the Jardin des Plantes in the 5th arrondissement (métro Place Monge). The galleries open to the public are the Gallery of Mineralogy and Geology, the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy, the Gallery of Botany, and the famous Gallery of Evolution (grande galerie de l'Évolution). The Paleontology and comparative Anatomy Gallery is a 540 million year journey and one of the highlights of the museum. It starts with the famous fossils from the Paleozoic Era from 540 to 250 million years ago, such as the gigantic Dunkleosteus. The Mesozoic Era, 250 to 65 million years ago, marks the golden age of the dinosaurs such as the Diplodocus, Iguanodon, Carnotaurus, Triceratops. One contemporary of these animals was Sarcosuchus, a giant crocodile with terrifying teeth. [10] The Muséum's Menagerie is also located in the Jardin des plantes.

The current Gallery of Botany, erected in 1935, is intended to preserve the vast herbarium of the museum. Referred to by code P, the herbarium includes a large number of important collections amongst its 8 million plant specimens. The historical collections incorporated into the herbarium, each with its P prefix, include those of Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck (P-LA) René Louiche Desfontaines (P-Desf.), Joseph Pitton de Tournefort and Charles Plumier (P-TRF). The bryophyte collection contains 900,000 specimens collected by notable bryologists including Sébastien Vaillant, Jean-Baptiste Mougeot, Camille Montagne, Wilhelm Philippe Schimper, Émile Bescherelle, Irénée Thériot, and Pierre Allorge.[11] The designation at CITES is FR 75A. It publishes the botanical periodical Adansonia and journals on the flora of New Caledonia, Madagascar, and Comoro Islands, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, Cameroon, and Gabon.[12]

The musée de l'Homme is also in Paris, in the 16th arrondissement (métro Trocadéro). It houses displays in ethnography and physical anthropology, including artifacts, fossils, and other objects.

Also part of the museum are:

- Three zoos, the Paris Zoological Park (Parc zoologique de Paris, also known as the Zoo de Vincennes), at the Bois de Vincennes in the 12th arrondissement, the Cleres Zoological Park (Parc zoologique de Clères), at a medieval manor in Clères (Seine-Maritime), and the Réserve de la Haute Touche in Obterre (Indre), the largest in France.

- Three botanical parks, the Arboretum de Chèvreloup in Rocquencourt next to the Château de Versailles, the Jardin botanique exotique de Menton and the Jardin alpin de La Jaÿsinia in Samoëns.

- Two museums, the Musée de l'abri Pataud in Les Eyzies-de-Tayac and the Harmas de Fabre in Sérignan-du-Comtat,

- Four scientific sites, the Institut de Paléontologie humaine in Paris, the Centre d'Écologie générale de Brunoy, the Station de Biologie marine et Marinarium de Concarneau, and the CRESCO (Centre de Recherche et d'Enseignement sur les Systèmes Côtiers) in Dinard.

Chairs

The transformation of the Jardin from the medicinal garden of the King to a national public museum of natural history required the creation of twelve chaired positions. Over the ensuing years the number of Chairs and their subject areas evolved, some being subdivided into two positions and others removed. The list of Chairs of the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle includes major figures in the history of the Natural sciences. Early chaired positions were held by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, René Desfontaines and Georges Cuvier, and later occupied by Paul Rivet, Léon Vaillant and others.

In popular culture

The Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy and other parts of Jardin des Plantes was a source of inspiration for French graphic novelist Jacques Tardi. The gallery appears on the first page and several subsequent pages of Adèle et la bête (Adèle and the Beast; 1976), the first album in the series of Les Aventures extraordinaires d'Adèle Blanc-Sec. The story opens with a 136-million-year-old pterodactyl egg hatching, and a live pterodactyl escaping through the gallery glass roof, wreaking havoc and killing people in Paris (the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy returned the favor by placing a life size cardboard cutout of Adèle and the hatching pterodactyl in a glass cabinet outside the main entrance on the top floor balcony).

Directors

Directors elected for one year:

- 1793 to 1794 : Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton

- 1794 to 1795 : Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu

- 1795 to 1796 : Bernard Germain Étienne de Laville-sur-Illon, comte de Lacépède

- 1796 to 1797 : Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton

- 1797 to 1798 : Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton

- 1798 to 1799 : Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu

- 1799 to 1800 : Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu

Directors elected for two years:

- 1800 to 1801 : Antoine-François Fourcroy

- 1802 to 1803 : René Desfontaines

- 1804 to 1805 : Antoine-François Fourcroy

- 1806 to 1807 : René Desfontaines

- 1808 to 1809 : Georges Cuvier

- 1810 to 1811 : René Desfontaines

- 1812 to 1813 : André Laugier

- 1814 to 1815 : André Thouin

- 1816 to 1817 : André Thouin

- 1818 to 1819 : André Laugier

- 1820 to 1821 : René Desfontaines

- 1822 to 1823 : Georges Cuvier

- 1824 to 1825 : Louis Cordier

- 1826 to 1827 : Georges Cuvier

- 1828 to 1829 : René Desfontaines

- 1830 to 1831 : Georges Cuvier

- 1832 to 1833 : Louis Cordier

- 1834 to 1835 : Adrien de Jussieu

- 1836 to 1837 : Michel Eugène Chevreul

- 1838 to 1839 : Louis Cordier

- 1840 to 1841 : Michel Eugène Chevreul

- 1842 to 1843 : Adrien de Jussieu

- 1844 to 1845 : Michel Eugène Chevreul

- 1846 to 1847 : Adolphe Brongniart

- 1848 to 1849 : Adrien de Jussieu

- 1850 to 1851 : Michel Eugène Chevreul

- 1852 to 1853 : André Marie Constant Duméril

- 1854 to 1855 : Michel Eugène Chevreul

- 1856 to 1857 : Marie Jean Pierre Flourens

- 1858 to 1859 : Michel Eugène Chevreul

- 1860 to 1861 : Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

- 1862 to 1863 : Michel Eugène Chevreul

Directors elected for five years:

- 1863 to 1879 : Michel Eugène Chevreul

- 1879 to 1891 : Edmond Frémy

- 1891 to 1900 : Alphonse Milne-Edwards

- 1900 to 1919 : Edmond Perrier

- 1919 to 1931 : Louis Mangin

- 1932 to 1936 : Paul Lemoine

- 1936 to 1942 : Louis Germain

- 1942 to 1949 : Achille Urbain

- 1950 to 1950 : René Jeannel

- 1951 to 1965 : Roger Heim

- 1966 to 1970 : Maurice Fontaine

- 1971 to 1975 : Yves Le Grand

- 1976 to 1985 : Jean Dorst

- 1985 to 1990 : Philippe Taquet

- 1994 to 1999 : Henry de Lumley

Presidents elected for five years:

- 2002 to 2006 : Bernard Chevassus-au-Louis

- 2006 to 2008 : André Menez (deceased in February 2008)

- 2008 to 2015: Gilles Boeuf

- 2015 to ...: Bruno David[13]

Friends

The Friends of the Natural History Museum Paris is a private organization that provides financial support for the museum, its branches and the Jardin des Plantes. Membership includes free entry to all galleries of the museum and the botanical garden. The Friends have assisted the museum with many purchases for its collections over the years, as well as funds for scientific and structural development.

See also

- List of museums in Paris

- People of the National Museum of Natural History

References

- "Management and preservation of the collections". Muséum national d'histoire naturelle. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- A. Allisy (November 1, 1996). "Henri Becquerel: The Discovery of Radioactivity". Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 68 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a031848.

- Alex Levine; Adriana Novoa (5 January 2012). ¡Darwinistas! The Construction of Evolutionary Thought in Nineteenth Century Argentina. BRILL. p. 85. ISBN 978-90-04-22136-9.

- Barquez, Rubén M.; Díaz, M. Mónica (2014). "History of mammalogy in Argentina" (PDF). In Ortega, José; Martínez, José Luis; Tirira, Diego G. (eds.). Historia de la mastozoología en Latinoamérica, las Guayanas y el Caribe (in Spanish). Editorial Murciélago Blanco y Asociación Ecuatoriana de Mastozoología. pp. 15–50. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- Adriana Novoa; Alex Levine (1 December 2010). From Man to Ape: Darwinism in Argentina, 1870–1920. University of Chicago Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-226-59616-7.

- Heintzman, Kit (2018). "A cabinet of the ordinary: domesticating veterinary education, 1766–1799". The British Journal for the History of Science. 51 (2): 239–260. doi:10.1017/S0007087418000274. PMID 29665887.

- Muséum national d'histoire naturelle; official website Archived 2008-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Official website Archived 2010-08-30 at the Wayback Machine

- "Implantations, site of the MNHN". Archived from the original on 2012-07-09. Retrieved 2012-05-25.

- "Natural History Museum Paris". Paris Digest. 2018. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- Bryophytes - Muséum national d'histoire naturelle

- P. K. Holmgren; N. H. Holmgren (2008). "Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle". Index Herbariorum. The New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- Bruno David - Muséum national d'histoire naturelle

External links

Wikidata has the property:

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muséum national d'histoire naturelle. |