Flamingo

Flamingos or flamingoes[1] /fləˈmɪŋɡoʊz/ are a type of wading bird in the family Phoenicopteridae, the only bird family in the order Phoenicopteriformes. Four flamingo species are distributed throughout the Americas, including the Caribbean, and two species are native to Africa, Asia, and Europe.

| Flamingos | |

|---|---|

| |

| James's flamingos (P. jamesi) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Phoenicopteriformes |

| Family: | Phoenicopteridae Bonaparte, 1831 |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

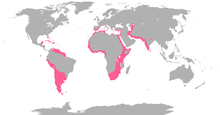

| |

| Global distribution of flamingos | |

Etymology

The name "flamingo" comes from Portuguese or Spanish flamengo, "flame-colored", in turn coming from Provençal flamenc from flama "flame" and Germanic-like suffix -ing, with a possible influence of the Spanish ethnonym flamenco "Fleming" or "Flemish". The generic name Phoenicopterus (from Greek: φοινικόπτερος phoinikopteros), literally means "blood red-feathered" has a similar etymology to the common name[2]; other genera include Phoeniconaias, which means "crimson/red water nymph (or naiad)", and Phoenicoparrus, which means "crimson/red bird (though, an unknown bird of omen)".

Taxonomy and systematics

Traditionally, the long-legged Ciconiiformes, probably a paraphyletic assemblage, have been considered the flamingos' closest relatives and the family was included in the order. Usually, the ibises and spoonbills of the Threskiornithidae were considered their closest relatives within this order. Earlier genetic studies, such as those of Charles Sibley and colleagues, also supported this relationship.[3] Relationships to the waterfowl were considered as well,[4] especially as flamingos are parasitized by feather lice of the genus Anaticola, which are otherwise exclusively found on ducks and geese.[5] The peculiar presbyornithids were used to argue for a close relationship between flamingos, waterfowl, and waders.[6] A 2002 paper concluded they are waterfowl,[7] but a 2014 comprehensive study of bird orders found that flamingos and grebes are not waterfowl, but rather are part of Columbea along with doves, sandgrouse, and mesites.[8]

Relationship with grebes

-_Breeding_plumage_W2_IMG_8770.jpg)

Recent molecular studies have suggested a relation with grebes,[9][10][11] while morphological evidence also strongly supports a relationship between flamingos and grebes. They hold at least 11 morphological traits in common, which are not found in other birds. Many of these characteristics have been previously identified on flamingos, but not on grebes.[12] The fossil palaelodids can be considered evolutionarily, and ecologically, intermediate between flamingos and grebes.[13]

For the grebe-flamingo clade, the taxon Mirandornithes ("miraculous birds" due to their extreme divergence and apomorphies) has been proposed. Alternatively, they could be placed in one order, with Phoenocopteriformes taking priority.[13]

Phylogeny

Living flamingos:[14]

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

Species

Six extant flamingo species are recognized by most sources, and were formerly placed in one genus (have common characteristics) – Phoenicopterus. As a result of a 2014 publication,[15] the family was reclassified into two genera.[16] Currently, the family has three recognized genera, according to HBW.[17]

| Image | Species | Geographic location | |

|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) |

Greater flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus) |

Old World | Parts of Africa, S. Europe and S. and SW Asia (most widespread flamingo). |

|

Lesser flamingo (Phoeniconaias minor) |

Africa (e.g. Great Rift Valley) to NW India (most numerous flamingo). | |

| Chilean flamingo (Phoenicopterus chilensis) |

New World | Temperate S. South America. | |

|

James's flamingo (Phoenicoparrus jamesi) |

High Andes in Peru, Chile, Bolivia and Argentina. | |

|

Andean flamingo (Phoenicoparrus andinus) |

High Andes in Peru, Chile, Bolivia and Argentina. | |

| American flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) |

Caribbean islands, Caribbean Mexico, southern Florida,[18] Belize, coastal Colombia, northern Brazil, Venezuela and Galápagos Islands. | ||

Prehistoric species of flamingo:

- Phoenicopterus floridanus Brodkorb 1953 (Early Pliocene of Florida)

- Phoenicopterus stocki (Miller 1944) (Middle Pliocene of Rincón, Mexico)

- Phoenicopterus siamensis Cheneval et al. 1991

- Phoenicopterus gracilis Miller 1963 (Early Pleistocene of Lake Kanunka, Australia)

- Phoenicopterus copei (Late Pleistocene of W North America and C. Mexico)

- Phoenicopterus minutus (Late Pleistocene of California, US)

- Phoenicopterus croizeti (Middle Oligocene – Middle Miocene of C. Europe)

- Phoenicopterus aethiopicus

- Phoenicopterus eyrensis (Late Oligocene of South Australia)

- Phoenicopterus novaehollandiae (Late Oligocene of South Australia)

Description

Flamingos usually stand on one leg while the other is tucked beneath their bodies. The reason for this behaviour is not fully understood. One theory is that standing on one leg allows the birds to conserve more body heat, given that they spend a significant amount of time wading in cold water.[19] However, the behaviour also takes place in warm water and is also observed in birds that do not typically stand in water. An alternative theory is that standing on one leg reduces the energy expenditure for producing muscular effort to stand and balance on one leg. A study on cadavers showed that the one-legged pose could be held without any muscle activity, while living flamingos demonstrate substantially less body sway in a one-legged posture.[20] As well as standing in the water, flamingos may stamp their webbed feet in the mud to stir up food from the bottom.[21]

Flamingos are capable flyers, and flamingos in captivity often require wing clipping to prevent escape. A pair of African flamingos which had not yet had their wings clipped escaped from the Wichita, Kansas zoo in 2005. One was spotted in Texas 14 years later. It had been seen previously by birders in Texas, Wisconsin and Louisiana.[22]

Young flamingos hatch with grayish-red plumage, but adults range from light pink to bright red due to aqueous bacteria and beta-carotene obtained from their food supply. A well-fed, healthy flamingo is more vibrantly colored, thus a more desirable mate; a white or pale flamingo, however, is usually unhealthy or malnourished. Captive flamingos are a notable exception; they may turn a pale pink if they are not fed carotene at levels comparable to the wild.[23]

The greater flamingo is the tallest of the six different species of flamingos, standing at 3.9 to 4.7 feet (1.2 to 1.4 m) with a weight up to 7.7 pounds (3.5 kg), and the shortest flamingo species (the lesser) has a height of 2.6 feet (0.8 m) and weighs 5.5 pounds (2.5 kg). Flamingos can have a wingspan as small as 37 inches (94 cm) to as big as 59 inches (150 cm).[24]

Flamingoes can open their bills by raising the upper jaw as well as by dropping the lower. [25]

Behavior and ecology

Feeding

Flamingos filter-feed on brine shrimp and blue-green algae as well as insect larvae, small insects, mollusks and crustaceans making them omnivores. Their bills are specially adapted to separate mud and silt from the food they eat, and are uniquely used upside-down. The filtering of food items is assisted by hairy structures called lamellae, which line the mandibles, and the large, rough-surfaced tongue. The pink or reddish color of flamingos comes from carotenoids in their diet of animal and plant plankton. American flamingos are a brighter red color because of the beta carotene availability in their food while the lesser flamingos are a paler pink due to ingesting a smaller amount of this pigment. These carotenoids are broken down into pigments by liver enzymes.[26] The source of this varies by species, and affects the color saturation. Flamingos whose sole diet is blue-green algae are darker than those that get it second-hand by eating animals that have digested blue-green algae).[27]

Lifecycle

Flamingos are very social birds; they live in colonies whose population can number in the thousands. These large colonies are believed to serve three purposes for the flamingos: avoiding predators, maximizing food intake, and using scarcely suitable nesting sites more efficiently.[28] Before breeding, flamingo colonies split into breeding groups of about 15 to 50 birds. Both males and females in these groups perform synchronized ritual displays.[29] The members of a group stand together and display to each other by stretching their necks upwards, then uttering calls while head-flagging, and then flapping their wings.[30] The displays do not seem directed towards an individual, but occur randomly.[30] These displays stimulate "synchronous nesting" (see below) and help pair up those birds that do not already have mates.[29]

Flamingos form strong pair bonds, although in larger colonies, flamingos sometimes change mates, presumably because more mates are available to choose.[31] Flamingo pairs establish and defend nesting territories. They locate a suitable spot on the mudflat to build a nest (the female usually selects the place).[30] Copulation usually occurs during nest building, which is sometimes interrupted by another flamingo pair trying to commandeer the nesting site for their use. Flamingos aggressively defend their nesting sites. Both the male and the female contribute to building the nest, and to protecting the nest and egg.[32] Same-sex pairs have been reported.[33]

After the chicks hatch, the only parental expense is feeding.[34] Both the male and the female feed their chicks with a kind of crop milk, produced in glands lining the whole of the upper digestive tract (not just the crop). The hormone prolactin stimulates production. The milk contains fat, protein, and red and white blood cells. (Pigeons and doves—Columbidae—also produce crop milk (just in the glands lining the crop), which contains less fat and more protein than flamingo crop milk.)[35]

For the first six days after the chicks hatch, the adults and chicks stay in the nesting sites. At around 7–12 days old, the chicks begin to move out of their nests and explore their surroundings. When they are two weeks old, the chicks congregate in groups, called "microcrèches", and their parents leave them alone. After a while, the microcrèches merge into "crèches" containing thousands of chicks. Chicks that do not stay in their crèches are vulnerable to predators.[36]

Status and conservation

In captivity

The first flamingo hatched in a European zoo was a Chilean flamingo at Zoo Basel in Switzerland in 1958. Since then, over 389 flamingos have grown up in Basel and been distributed to other zoos around the globe.[37]

Greater, an at least 83-year-old greater flamingo, believed to be the oldest in the world, died at the Adelaide Zoo in Australia in January 2014.[38]

Relationship with humans

- Ancient Romans considered their tongues a delicacy.[39]

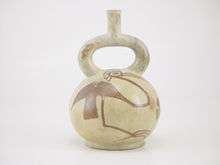

- In the Americas, the Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped nature.[40] They placed emphasis on animals, and often depicted flamingos in their art.[41]

- Flamingos are the national bird of the Bahamas.

- Andean miners have killed flamingos for their fat, believing that it would cure tuberculosis.[42]

- In the United States, pink plastic flamingo statues are popular lawn ornaments.[43]

References

- Both forms of the plural are attested, according to the Oxford English Dictionary

- Harper, Douglas. "flamingo". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Salzman, Eric (December 1993). "Sibley's Classification of Birds". Ornitologia e dintorni. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- Sibley, Charles G.; Corbin, Kendall W.; Haavie, Joan H. (1969). "The Relationships of the Flamingos as Indicated by the Egg-White Proteins and Hemoglobins" (PDF). Condor. 71 (2): 155–179. doi:10.2307/1366077. JSTOR 1366077.

- Johnson, Kevin P.; Kennedy, Martyn; McCracken, Kevin G. (2006). "Reinterpreting the origins of flamingo lice: cospeciation or host-switching?" (PDF). Biology Letters. 2 (2): 275–278. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0427. PMC 1618896. PMID 17148381. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- Feduccia, Alan (1976). "Osteological evidence for shorebird affinities of the flamingos" (PDF). Auk. 93 (3): 587. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- Kurochkin, E. N.; Dyke, G. J.; Karhu, A. A. (2002). "A New Presbyornithid Bird (Aves, Anseriformes) from the Late Cretaceous of Southern Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 3386: 1–11. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2002)386<0001:ANPBAA>2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/2875.

- Jarvis, E.D.; et al. (2014). "Whole-genome analyses resolve early branches in the tree of life of modern birds". Science. 346 (6215): 1320–1331. Bibcode:2014Sci...346.1320J. doi:10.1126/science.1253451. PMC 4405904. PMID 25504713.

- Chubb, AL (2004). "New nuclear evidence for the oldest divergence among neognath birds: the phylogenetic utility of ZENK (i)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 30 (1): 140–151. doi:10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00159-3. PMID 15022765.

- Ericson, Per G. P.; Anderson, CL; Britton, T; Elzanowski, A; Johansson, US; Källersjö, M; Ohlson, JI; Parsons, TJ; Zuccon, D (December 2006). "Diversification of Neoaves: integration of molecular sequence data and fossils" (PDF). Biology Letters. 2 (4): 543–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0523. PMC 1834003. PMID 17148284. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- Hackett, Shannon J.; Kimball, Rebecca T.; Reddy, Sushma; Bowie, Rauri C. K.; Braun, Edward L.; Braun, Michael J.; Chojnowski, Jena L.; Cox, W. Andrew; Kin-Lan Han, John (27 June 2008). "A Phylogenomic Study of Birds Reveals Their Evolutionary History". Science. 320 (5884): 1763–1768. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1763H. doi:10.1126/science.1157704. PMID 18583609.

- Mayr, Gerald (2004). "Morphological evidence for sister group relationship between flamingos (Aves: Phoenicopteridae) and grebes (Podicipedidae)" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 140 (2): 157–169. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2003.00094.x. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- Mayr, Gerald (2006). "The contribution of fossils to the reconstruction of the higher-level phylogeny of birds" (PDF). Species, Phylogeny and Evolution. 3: 59–64. ISSN 1098-660X. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Boyd, John (2007). "NEOAVES- COLUMBEA". John Boyd's website. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- Torres, Chris R; Ogawa, Lisa M; Gillingham, Mark AF; Ferrari, Brittney; Van Tuinen, Marcel (2014). "A multi-locus inference of the evolutionary diversification of extant flamingos (Phoenicopteridae)". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14 (1): 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-36. PMC 4016592. PMID 24580860.

- Gill, F and D Donsker (Eds). (2016). IOC World Bird List (v 6.3).

- "Lesser Flamingo (Phoeniconaias minor)". www.hbw.com. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Scientists: Florida flamingos are native to the state, News-Press, Chad Gillis, February 23, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- Walker, Matt (13 August 2009). "Why flamingoes stand on one leg". BBC News. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- Chang, Young-Hui; Ting, Lena H. (24 May 2017). "Mechanical evidence that flamingos can support their body on one leg with little active muscular force". Biology Letters. 13 (5): 20160948. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2016.0948. PMC 5454233. PMID 28539457.

- Bildstein, Keith L.; Frederick, Peter C.; Spalding, Marilyn G. (November 1991). "Feeding Patterns and Aggressive Behavior in Juvenile and Adult American Flamingos". The Condor. 93 (4): 916–925. doi:10.2307/3247726. JSTOR 3247726.

- Fugitive flamingo spotted in Texas 14 years after escaping a Kansas zoo during storm, Wichita Eagle, Kaitlyn Alanis, May 27, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- Grazian, David (2015). American Zoo: A Sociological Safari. Princeton, NJ, US: Princeton University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-691-16435-9.

- Bradford, Alina. 2014. Flamingo Facts: Food Turns Feathers Pink. September 18. Accessed March 2018. https://www.livescience.com/27322-flamingos.html

- Jenkin, Penelope M. (9 May 1957). "The filter-feeding and food of flamingoes (Pheonicopteri)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 240 (674): 401–493., page 409.

- Hill, G. E.; Montgomerie, R.; Inouye, C. Y.; Dale, J. (June 1994). "Influence of Dietary Carotenoids on Plasma and Plumage Colour in the House Finch: Intra- and Intersexual Variation". Functional Ecology. 8 (3): 343–350. doi:10.2307/2389827. JSTOR 2389827.

- "NATURE: Fire Bird – Flamingo Facts". Pbs.org. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- Pickett, C.; Stevens, E. F. (1994). "Managing the Social Environments of Flamingos for Reproductive Success". Zoo Biology. 13 (5): 501–507. doi:10.1002/zoo.1430130512.

- Ogilvie, Malcolm; Carol Ogilvie (1986). Flamingos. Gloucester, UK: Alan Sutton Publishing Limited. ISBN 9780862992668. OCLC 246861013.

- Studer-Thiersch, A. (1975). "Basle Zoo", pp. 121–130 in N. Duplaix-Hall and J. Kear, editors. Flamingos. Berkhamsted, United Kingdom: T. & A. D. Poyser, ISBN 140813750X.

- Studer-Thiersch, A. (2000). "What 19 Years of Observation on Captive Great Flamingos Suggests about Adaptations to Breeding under Irregular Conditions." Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology 23 (Special Publication I: Conservation Biology of Flamingos): 150–159.

- Johnson, Alan; Cézilly, Frank (1975). The Greater Flamingo. London: T & AD Poyser Ltd. pp. 124–130. ISBN 978-1-4081-3866-3.

- Bagemihl, Bruce (1999). Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity. Stonewall Inn Editions. pp. 524–7. ISBN 978-0312253776.

- Cézilly, F.; Johnson, A.; Tourenq, C. (1994). "Variation in Parental Care with Offspring Age in the Greater Flamingo". The Condor. 96 (3): 809–812. doi:10.2307/1369487. JSTOR 1369487.

- Ehrlich, Paul; Dobkin, David S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988). The Birder's Handbook. New York, NY, US: Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-671-62133-9.

- Gaillo, A.; Johnson, A. R.; Gallo, A. (1995). "Adult Aggressiveness and Crèching Behavior in the Greater Flamingo, Phoenicopterus ruber roseus". Colonial Waterbirds. 18 (2): 216–221. doi:10.2307/1521484. JSTOR 1521484.

- "Zolli feiert 50 Jahre Flamingozucht und Flamingosforschung" [Zolli celebrates 50 years of flamingo breeding and science]. Basler Zeitung (in German). 13 August 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- Fedorowytsch, Tom (31 January 2014). "Flamingo believed to be world's oldest dies at Adelaide Zoo aged 83". ABC Radio Australia. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- "Flamingo Feeding". Stanford University. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- Benson, Elizabeth (1972) The Mochica: A Culture of Peru. New York, NY: Praeger Press.

- Berrin, Katherine; Larco Museum (1997). The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500018026.

- "Flamingos". Seaworld.org. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- Collins, Clayton (2 November 2006). "Backstory: Extinction of an American icon?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Phoenicopteridae |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phoenicopterus. |

- Flamingo Resource Centre

- Flamingo videos and photos on the Internet Bird Collection