Extinction event

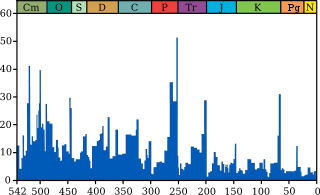

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp change in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. It occurs when the rate of extinction increases with respect to the rate of speciation. Estimates of the number of major mass extinctions in the last 540 million years range from as few as five to more than twenty. These differences stem from the threshold chosen for describing an extinction event as "major", and the data chosen to measure past diversity.

Because most diversity and biomass on Earth is microbial, and thus difficult to measure, recorded extinction events affect the easily observed, biologically complex component of the biosphere rather than the total diversity and abundance of life.[1] Extinction occurs at an uneven rate. Based on the fossil record, the background rate of extinctions on Earth is about two to five taxonomic families of marine animals every million years. Marine fossils are mostly used to measure extinction rates because of their superior fossil record and stratigraphic range compared to land animals.

The Great Oxygenation Event, which occurred around 2.45 billion years ago, was probably the first major extinction event.[2] Since the Cambrian explosion, five further major mass extinctions have significantly exceeded the background extinction rate. The most recent and arguably best-known, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, which occurred approximately 66 million years ago (Ma), was a large-scale mass extinction of animal and plant species in a geologically short period of time.[3] In addition to the five major mass extinctions, there are numerous minor ones as well, and the ongoing mass extinction caused by human activity is sometimes called the sixth extinction.[4] Mass extinctions seem to be a mainly Phanerozoic phenomenon, with extinction rates low before large complex organisms arose.[5]

Major extinction events

In a landmark paper published in 1982, Jack Sepkoski and David M. Raup identified five mass extinctions. They were originally identified as outliers to a general trend of decreasing extinction rates during the Phanerozoic,[6] but as more stringent statistical tests have been applied to the accumulating data, it has been established that multicellular animal life has experienced five major and many minor mass extinctions.[7] The "Big Five" cannot be so clearly defined, but rather appear to represent the largest (or some of the largest) of a relatively smooth continuum of extinction events.[6]

- Ordovician–Silurian extinction events (End Ordovician or O–S): 450–440 Ma (million years ago) at the Ordovician–Silurian transition. Two events occurred that killed off 27% of all families, 57% of all genera and 60% to 70% of all species.[8] Together they are ranked by many scientists as the second largest of the five major extinctions in Earth's history in terms of percentage of genera that became extinct.

- Late Devonian extinction: 375–360 Ma near the Devonian–Carboniferous transition. At the end of the Frasnian Age in the later part(s) of the Devonian Period, a prolonged series of extinctions eliminated about 19% of all families, 50% of all genera[8] and at least 70% of all species.[9] This extinction event lasted perhaps as long as 20 million years, and there is evidence for a series of extinction pulses within this period.

- Permian–Triassic extinction event (End Permian): 252 Ma at the Permian–Triassic transition.[10] Earth's largest extinction killed 57% of all families, 83% of all genera and 90% to 96% of all species[8] (53% of marine families, 84% of marine genera, about 96% of all marine species and an estimated 70% of land species,[3] including insects).[11] The highly successful marine arthropod, the trilobite, became extinct. The evidence regarding plants is less clear, but new taxa became dominant after the extinction.[12] The "Great Dying" had enormous evolutionary significance: on land, it ended the primacy of mammal-like reptiles. The recovery of vertebrates took 30 million years,[13] but the vacant niches created the opportunity for archosaurs to become ascendant. In the seas, the percentage of animals that were sessile dropped from 67% to 50%. The whole late Permian was a difficult time for at least marine life, even before the "Great Dying".

- Triassic–Jurassic extinction event (End Triassic): 201.3 Ma at the Triassic–Jurassic transition. About 23% of all families, 48% of all genera (20% of marine families and 55% of marine genera) and 70% to 75% of all species became extinct.[8] Most non-dinosaurian archosaurs, most therapsids, and most of the large amphibians were eliminated, leaving dinosaurs with little terrestrial competition. Non-dinosaurian archosaurs continued to dominate aquatic environments, while non-archosaurian diapsids continued to dominate marine environments. The Temnospondyl lineage of large amphibians also survived until the Cretaceous in Australia (e.g., Koolasuchus).

- Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (End Cretaceous, K–Pg extinction, or formerly K–T extinction): 66 Ma at the Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) – Paleogene (Danian) transition interval.[14] The event formerly called the Cretaceous-Tertiary or K–T extinction or K–T boundary is now officially named the Cretaceous–Paleogene (or K–Pg) extinction event. About 17% of all families, 50% of all genera[8] and 75% of all species became extinct.[15] In the seas all the ammonites, plesiosaurs and mosasaurs disappeared and the percentage of sessile animals (those unable to move about) was reduced to about 33%. All non-avian dinosaurs became extinct during that time.[16] The boundary event was severe with a significant amount of variability in the rate of extinction between and among different clades. Mammals and birds, the latter descended from theropod dinosaurs, emerged as dominant large land animals.

Despite the popularization of these five events, there is no definite line separating them from other extinction events; using different methods of calculating an extinction's impact can lead to other events featuring in the top five.[17]

Older fossil records are more difficult to interpret. This is because:

- Older fossils are harder to find as they are usually buried at a considerable depth.

- Dating older fossils is more difficult.

- Productive fossil beds are researched more than unproductive ones, therefore leaving certain periods unresearched.

- Prehistoric environmental events can disturb the deposition process.

- The preservation of fossils varies on land, but marine fossils tend to be better preserved than their sought after land-based counterparts.[18]

It has been suggested that the apparent variations in marine biodiversity may actually be an artifact, with abundance estimates directly related to quantity of rock available for sampling from different time periods.[19] However, statistical analysis shows that this can only account for 50% of the observed pattern, and other evidence (such as fungal spikes) provides reassurance that most widely accepted extinction events are real. A quantification of the rock exposure of Western Europe indicates that many of the minor events for which a biological explanation has been sought are most readily explained by sampling bias.[20]

Research completed after the seminal 1982 paper has concluded that a sixth mass extinction event is ongoing:

- 6. Holocene extinction: Currently ongoing. Extinctions have occurred at over 1000 times the background extinction rate since 1900.[21][22] The mass extinction is a result of human activity.[23][24][25] The 2019 global biodiversity assessment by IPBES asserts that out of an estimated 8 million species, 1 million plant and animal species are currently threatened with extinction.[26][27][28][29]

More recent research has indicated that the End-Capitanian extinction event likely constitutes a separate extinction event from the Permian–Triassic extinction event; if so, it would be larger than many of the "Big Five" extinction events.

List of extinction events

Evolutionary importance

Mass extinctions have sometimes accelerated the evolution of life on Earth. When dominance of particular ecological niches passes from one group of organisms to another, it is rarely because the new dominant group is "superior" to the old and usually because an extinction event eliminates the old dominant group and makes way for the new one.[30][31]

For example, mammaliformes ("almost mammals") and then mammals existed throughout the reign of the dinosaurs, but could not compete for the large terrestrial vertebrate niches which dinosaurs monopolized. The end-Cretaceous mass extinction removed the non-avian dinosaurs and made it possible for mammals to expand into the large terrestrial vertebrate niches. Ironically, the dinosaurs themselves had been beneficiaries of a previous mass extinction, the end-Triassic, which eliminated most of their chief rivals, the crurotarsans.

Another point of view put forward in the Escalation hypothesis predicts that species in ecological niches with more organism-to-organism conflict will be less likely to survive extinctions. This is because the very traits that keep a species numerous and viable under fairly static conditions become a burden once population levels fall among competing organisms during the dynamics of an extinction event.

Furthermore, many groups which survive mass extinctions do not recover in numbers or diversity, and many of these go into long-term decline, and these are often referred to as "Dead Clades Walking".[32] However, clades that survive for a considerable period of time after a mass extinction, and which were reduced to only a few species, are likely to have experienced a rebound effect called the "push of the past".[33]

Darwin was firmly of the opinion that biotic interactions, such as competition for food and space—the ‘struggle for existence’—were of considerably greater importance in promoting evolution and extinction than changes in the physical environment. He expressed this in The Origin of Species: "Species are produced and exterminated by slowly acting causes…and the most import of all causes of organic change is one which is almost independent of altered…physical conditions, namely the mutual relation of organism to organism-the improvement of one organism entailing the improvement or extermination of others".[34]

Patterns in frequency

It has been suggested variously that extinction events occurred periodically, every 26 to 30 million years,[35][36] or that diversity fluctuates episodically every ~62 million years.[37] Various ideas attempt to explain the supposed pattern, including the presence of a hypothetical companion star to the sun,[38][39] oscillations in the galactic plane, or passage through the Milky Way's spiral arms.[40] However, other authors have concluded that the data on marine mass extinctions do not fit with the idea that mass extinctions are periodic, or that ecosystems gradually build up to a point at which a mass extinction is inevitable.[6] Many of the proposed correlations have been argued to be spurious.[41][42] Others have argued that there is strong evidence supporting periodicity in a variety of records,[43] and additional evidence in the form of coincident periodic variation in nonbiological geochemical variables.[44]

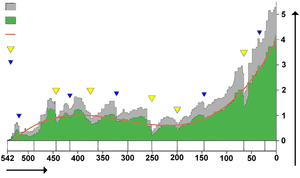

Mass extinctions are thought to result when a long-term stress is compounded by a short-term shock.[45] Over the course of the Phanerozoic, individual taxa appear to be less likely to become extinct at any time,[46] which may reflect more robust food webs as well as less extinction-prone species and other factors such as continental distribution.[46] However, even after accounting for sampling bias, there does appear to be a gradual decrease in extinction and origination rates during the Phanerozoic.[6] This may represent the fact that groups with higher turnover rates are more likely to become extinct by chance; or it may be an artefact of taxonomy: families tend to become more speciose, therefore less prone to extinction, over time;[6] and larger taxonomic groups (by definition) appear earlier in geological time.[47]

It has also been suggested that the oceans have gradually become more hospitable to life over the last 500 million years, and thus less vulnerable to mass extinctions,[note 1][48][49] but susceptibility to extinction at a taxonomic level does not appear to make mass extinctions more or less probable.[46]

Causes

There is still debate about the causes of all mass extinctions. In general, large extinctions may result when a biosphere under long-term stress undergoes a short-term shock.[45] An underlying mechanism appears to be present in the correlation of extinction and origination rates to diversity. High diversity leads to a persistent increase in extinction rate; low diversity to a persistent increase in origination rate. These presumably ecologically controlled relationships likely amplify smaller perturbations (asteroid impacts, etc.) to produce the global effects observed.[6]

Identifying causes of specific mass extinctions

A good theory for a particular mass extinction should: (i) explain all of the losses, not just focus on a few groups (such as dinosaurs); (ii) explain why particular groups of organisms died out and why others survived; (iii) provide mechanisms which are strong enough to cause a mass extinction but not a total extinction; (iv) be based on events or processes that can be shown to have happened, not just inferred from the extinction.

It may be necessary to consider combinations of causes. For example, the marine aspect of the end-Cretaceous extinction appears to have been caused by several processes which partially overlapped in time and may have had different levels of significance in different parts of the world.[50]

Arens and West (2006) proposed a "press / pulse" model in which mass extinctions generally require two types of cause: long-term pressure on the eco-system ("press") and a sudden catastrophe ("pulse") towards the end of the period of pressure.[51] Their statistical analysis of marine extinction rates throughout the Phanerozoic suggested that neither long-term pressure alone nor a catastrophe alone was sufficient to cause a significant increase in the extinction rate.

Most widely supported explanations

Macleod (2001)[52] summarized the relationship between mass extinctions and events which are most often cited as causes of mass extinctions, using data from Courtillot et al. (1996),[53] Hallam (1992)[54] and Grieve et al. (1996):[55]

- Flood basalt events: 11 occurrences, all associated with significant extinctions[56][57] But Wignall (2001) concluded that only five of the major extinctions coincided with flood basalt eruptions and that the main phase of extinctions started before the eruptions.[58]

- Sea-level falls: 12, of which seven were associated with significant extinctions.[57]

- Asteroid impacts: one large impact is associated with a mass extinction, i.e. the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event; there have been many smaller impacts but they are not associated with significant extinctions.[59]

The most commonly suggested causes of mass extinctions are listed below.

Flood basalt events

The formation of large igneous provinces by flood basalt events could have:

- produced dust and particulate aerosols which inhibited photosynthesis and thus caused food chains to collapse both on land and at sea[60]

- emitted sulfur oxides which were precipitated as acid rain and poisoned many organisms, contributing further to the collapse of food chains

- emitted carbon dioxide and thus possibly causing sustained global warming once the dust and particulate aerosols dissipated.

Flood basalt events occur as pulses of activity punctuated by dormant periods. As a result, they are likely to cause the climate to oscillate between cooling and warming, but with an overall trend towards warming as the carbon dioxide they emit can stay in the atmosphere for hundreds of years.

It is speculated that massive volcanism caused or contributed to the End-Permian, End-Triassic and End-Cretaceous extinctions.[61] The correlation between gigantic volcanic events expressed in the large igneous provinces and mass extinctions was shown for the last 260 Myr.[62][63] Recently such possible correlation was extended for the whole Phanerozoic Eon.[64]

Sea-level falls

These are often clearly marked by worldwide sequences of contemporaneous sediments which show all or part of a transition from sea-bed to tidal zone to beach to dry land – and where there is no evidence that the rocks in the relevant areas were raised by geological processes such as orogeny. Sea-level falls could reduce the continental shelf area (the most productive part of the oceans) sufficiently to cause a marine mass extinction, and could disrupt weather patterns enough to cause extinctions on land. But sea-level falls are very probably the result of other events, such as sustained global cooling or the sinking of the mid-ocean ridges.

Sea-level falls are associated with most of the mass extinctions, including all of the "Big Five"—End-Ordovician, Late Devonian, End-Permian, End-Triassic, and End-Cretaceous.

A study, published in the journal Nature (online June 15, 2008) established a relationship between the speed of mass extinction events and changes in sea level and sediment.[65] The study suggests changes in ocean environments related to sea level exert a driving influence on rates of extinction, and generally determine the composition of life in the oceans.[66]

Impact events

The impact of a sufficiently large asteroid or comet could have caused food chains to collapse both on land and at sea by producing dust and particulate aerosols and thus inhibiting photosynthesis.[67] Impacts on sulfur-rich rocks could have emitted sulfur oxides precipitating as poisonous acid rain, contributing further to the collapse of food chains. Such impacts could also have caused megatsunamis and/or global forest fires.

Most paleontologists now agree that an asteroid did hit the Earth about 66 Ma ago, but there is an ongoing dispute whether the impact was the sole cause of the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.[68][69]

Nonetheless, in October 2019, researchers reported that the Cretaceous Chicxulub asteroid impact that resulted in the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs 66 Ma ago, also rapidly acidified the oceans producing ecological collapse and long-lasting effects on the climate, and was a key reason for end-Cretaceous mass extinction.[70][71]

Global cooling

Sustained and significant global cooling could kill many polar and temperate species and force others to migrate towards the equator; reduce the area available for tropical species; often make the Earth's climate more arid on average, mainly by locking up more of the planet's water in ice and snow. The glaciation cycles of the current ice age are believed to have had only a very mild impact on biodiversity, so the mere existence of a significant cooling is not sufficient on its own to explain a mass extinction.

It has been suggested that global cooling caused or contributed to the End-Ordovician, Permian–Triassic, Late Devonian extinctions, and possibly others. Sustained global cooling is distinguished from the temporary climatic effects of flood basalt events or impacts.

Global warming

This would have the opposite effects: expand the area available for tropical species; kill temperate species or force them to migrate towards the poles; possibly cause severe extinctions of polar species; often make the Earth's climate wetter on average, mainly by melting ice and snow and thus increasing the volume of the water cycle. It might also cause anoxic events in the oceans (see below).

Global warming as a cause of mass extinction is supported by several recent studies.[72]

The most dramatic example of sustained warming is the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, which was associated with one of the smaller mass extinctions. It has also been suggested to have caused the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event, during which 20% of all marine families became extinct. Furthermore, the Permian–Triassic extinction event has been suggested to have been caused by warming.[73][74][75]

Clathrate gun hypothesis

Clathrates are composites in which a lattice of one substance forms a cage around another. Methane clathrates (in which water molecules are the cage) form on continental shelves. These clathrates are likely to break up rapidly and release the methane if the temperature rises quickly or the pressure on them drops quickly—for example in response to sudden global warming or a sudden drop in sea level or even earthquakes. Methane is a much more powerful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, so a methane eruption ("clathrate gun") could cause rapid global warming or make it much more severe if the eruption was itself caused by global warming.

The most likely signature of such a methane eruption would be a sudden decrease in the ratio of carbon-13 to carbon-12 in sediments, since methane clathrates are low in carbon-13; but the change would have to be very large, as other events can also reduce the percentage of carbon-13.[76]

It has been suggested that "clathrate gun" methane eruptions were involved in the end-Permian extinction ("the Great Dying") and in the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, which was associated with one of the smaller mass extinctions.

Anoxic events

Anoxic events are situations in which the middle and even the upper layers of the ocean become deficient or totally lacking in oxygen. Their causes are complex and controversial, but all known instances are associated with severe and sustained global warming, mostly caused by sustained massive volcanism.[77]

It has been suggested that anoxic events caused or contributed to the Ordovician–Silurian, late Devonian, Permian–Triassic and Triassic–Jurassic extinctions, as well as a number of lesser extinctions (such as the Ireviken, Mulde, Lau, Toarcian and Cenomanian–Turonian events). On the other hand, there are widespread black shale beds from the mid-Cretaceous which indicate anoxic events but are not associated with mass extinctions.

The bio-availability of essential trace elements (in particular selenium) to potentially lethal lows has been shown to coincide with, and likely have contributed to, at least three mass extinction events in the oceans, i.e. at the end of the Ordovician, during the Middle and Late Devonian, and at the end of the Triassic. During periods of low oxygen concentrations very soluble selenate (Se6+) is converted into much less soluble selenide (Se2-), elemental Se and organo-selenium complexes. Bio-availability of selenium during these extinction events dropped to about 1% of the current oceanic concentration, a level that has been proven lethal to many extant organisms.[78]

British oceanologist and atmospheric scientist, Andrew Watson, explained that, while the Holocene epoch exhibits many processes reminiscent of those that have contributed to past anoxic events, full-scale ocean anoxia would take "thousands of years to develop".[79]

Hydrogen sulfide emissions from the seas

Kump, Pavlov and Arthur (2005) have proposed that during the Permian–Triassic extinction event the warming also upset the oceanic balance between photosynthesising plankton and deep-water sulfate-reducing bacteria, causing massive emissions of hydrogen sulfide which poisoned life on both land and sea and severely weakened the ozone layer, exposing much of the life that still remained to fatal levels of UV radiation.[80][81][82]

Oceanic overturn

Oceanic overturn is a disruption of thermo-haline circulation which lets surface water (which is more saline than deep water because of evaporation) sink straight down, bringing anoxic deep water to the surface and therefore killing most of the oxygen-breathing organisms which inhabit the surface and middle depths. It may occur either at the beginning or the end of a glaciation, although an overturn at the start of a glaciation is more dangerous because the preceding warm period will have created a larger volume of anoxic water.[83]

Unlike other oceanic catastrophes such as regressions (sea-level falls) and anoxic events, overturns do not leave easily identified "signatures" in rocks and are theoretical consequences of researchers' conclusions about other climatic and marine events.

It has been suggested that oceanic overturn caused or contributed to the late Devonian and Permian–Triassic extinctions.

A nearby nova, supernova or gamma ray burst

A nearby gamma-ray burst (less than 6000 light-years away) would be powerful enough to destroy the Earth's ozone layer, leaving organisms vulnerable to ultraviolet radiation from the Sun.[84] Gamma ray bursts are fairly rare, occurring only a few times in a given galaxy per million years.[85] It has been suggested that a supernova or gamma ray burst caused the End-Ordovician extinction.[86]

Geomagnetic reversal

One theory is that periods of increased geomagnetic reversals will weaken Earth's magnetic field long enough to expose the atmosphere to the solar winds, causing oxygen ions to escape the atmosphere in a rate increased by 3–4 orders, resulting in a disastrous decrease in oxygen.[87]

Plate tectonics

Movement of the continents into some configurations can cause or contribute to extinctions in several ways: by initiating or ending ice ages; by changing ocean and wind currents and thus altering climate; by opening seaways or land bridges which expose previously isolated species to competition for which they are poorly adapted (for example, the extinction of most of South America's native ungulates and all of its large metatherians after the creation of a land bridge between North and South America). Occasionally continental drift creates a super-continent which includes the vast majority of Earth's land area, which in addition to the effects listed above is likely to reduce the total area of continental shelf (the most species-rich part of the ocean) and produce a vast, arid continental interior which may have extreme seasonal variations.

Another theory is that the creation of the super-continent Pangaea contributed to the End-Permian mass extinction. Pangaea was almost fully formed at the transition from mid-Permian to late-Permian, and the "Marine genus diversity" diagram at the top of this article shows a level of extinction starting at that time which might have qualified for inclusion in the "Big Five" if it were not overshadowed by the "Great Dying" at the end of the Permian.[88]

Other hypotheses

Many other hypotheses have been proposed, such as the spread of a new disease, or simple out-competition following an especially successful biological innovation. But all have been rejected, usually for one of the following reasons: they require events or processes for which there is no evidence; they assume mechanisms which are contrary to the available evidence; they are based on other theories which have been rejected or superseded.

Scientists have been concerned that human activities could cause more plants and animals to become extinct than any point in the past. Along with human-made changes in climate (see above), some of these extinctions could be caused by overhunting, overfishing, invasive species, or habitat loss. A study published in May 2017 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences argued that a “biological annihilation” akin to a sixth mass extinction event is underway as a result of anthropogenic causes, such as over-population and over-consumption. The study suggested that as much as 50% of the number of animal individuals that once lived on Earth were already extinct, threatening the basis for human existence too.[89][25]

Future biosphere extinction/sterilization

The eventual warming and expanding of the Sun, combined with the eventual decline of atmospheric carbon dioxide could actually cause an even greater mass extinction, having the potential to wipe out even microbes (in other words, the Earth is completely sterilized), where rising global temperatures caused by the expanding Sun will gradually increase the rate of weathering, which in turn removes more and more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. When carbon dioxide levels get too low (perhaps at 50 ppm), all plant life will die out, although simpler plants like grasses and mosses can survive much longer, until CO

2 levels drop to 10 ppm.[90][91]

With all photosynthetic organisms gone, atmospheric oxygen can no longer be replenished, and is eventually removed by chemical reactions in the atmosphere, perhaps from volcanic eruptions. Eventually the loss of oxygen will cause all remaining aerobic life to die out via asphyxiation, leaving behind only simple anaerobic prokaryotes. When the Sun becomes 10% brighter in about a billion years,[90] Earth will suffer a moist greenhouse effect resulting in its oceans boiling away, while the Earth's liquid outer core cools due to the inner core's expansion and causes the Earth's magnetic field to shut down. In the absence of a magnetic field, charged particles from the Sun will deplete the atmosphere and further increase the Earth's temperature to an average of ~420 K (147 °C, 296 °F) in 2.8 billion years, causing the last remaining life on Earth to die out. This is the most extreme instance of a climate-caused extinction event. Since this will only happen late in the Sun's life, such will cause the final mass extinction in Earth's history (albeit a very long extinction event).[90][91]

Effects and recovery

The impact of mass extinction events varied widely. After a major extinction event, usually only weedy species survive due to their ability to live in diverse habitats.[92] Later, species diversify and occupy empty niches. Generally, it takes millions of years for biodiversity to recover after extinction events.[93] In the most severe mass extinctions it may take 15 to 30 million years.[92]

The worst event, the Permian–Triassic extinction, devastated life on earth, killing over 90% of species. Life seemed to recover quickly after the P-T extinction, but this was mostly in the form of disaster taxa, such as the hardy Lystrosaurus. The most recent research indicates that the specialized animals that formed complex ecosystems, with high biodiversity, complex food webs and a variety of niches, took much longer to recover. It is thought that this long recovery was due to successive waves of extinction which inhibited recovery, as well as prolonged environmental stress which continued into the Early Triassic. Recent research indicates that recovery did not begin until the start of the mid-Triassic, 4M to 6M years after the extinction;[94] and some writers estimate that the recovery was not complete until 30M years after the P-T extinction, i.e. in the late Triassic.[95] Subsequent to the P-T extinction, there was an increase in provincialization, with species occupying smaller ranges – perhaps removing incumbents from niches and setting the stage for an eventual rediversification.[96]

The effects of mass extinctions on plants are somewhat harder to quantify, given the biases inherent in the plant fossil record. Some mass extinctions (such as the end-Permian) were equally catastrophic for plants, whereas others, such as the end-Devonian, did not affect the flora.[97]

See also

- Bioevent

- Elvis taxon

- Endangered species

- Geologic time scale

- Global catastrophic risk

- Holocene extinction

- Human extinction

- Kačák Event

- Lazarus taxon

- List of impact craters on Earth

- List of largest volcanic eruptions

- List of possible impact structures on Earth

- Medea hypothesis

- Nature timeline

- Rare species

- Signor–Lipps effect

- Snowball Earth

- The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (nonfiction book)

- Timeline of extinctions in the Holocene

Notes

- Dissolved oxygen became more widespread and penetrated to greater depths; the development of life on land reduced the run-off of nutrients and hence the risk of eutrophication and anoxic events; and marine ecosystems became more diversified so that food chains were less likely to be disrupted.

References

- Nee, S. (2004). "Extinction, slime, and bottoms". PLoS Biology. 2 (8): E272. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020272. PMC 509315. PMID 15314670.

- Plait, Phil (28 July 2014). "Poisoned Planet". Slate. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- Ward, Peter D (2006). "Impact from the Deep". Scientific American. 295 (4): 64–71. Bibcode:2006SciAm.295d..64W. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1006-64. PMID 16989482.

-

- Kluger, Jeffrey (July 25, 2014). "The Sixth Great Extinction Is Underway – and We're to Blame". Time. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- The Sixth Extinction on YouTube (PBS Digital Studios, November 17, 2014)

- Kaplan, Sarah (June 22, 2015). "Earth is on brink of a sixth mass extinction, scientists say, and it's humans' fault". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- Hance, Jeremy (October 20, 2015). "How humans are driving the sixth mass extinction". The Guardian. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- "Vanishing: The Earth's 6th mass extinction". CNN. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- Butterfield, N.J. (2007). "Macroevolution and macroecology through deep time" (PDF). Palaeontology. 50 (1): 41–55. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00613.x.

- Alroy, J. (2008). "Dynamics of origination and extinction in the marine fossil record". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (Supplement 1): 11536–42. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511536A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802597105. PMC 2556405. PMID 18695240.

- Gould, S.J. (March 1, 2004). "The Evolution of Life on Earth". Scientific American. 271 (4): 84–91. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1094-84. PMID 7939569.

- "extinction". Math.ucr.edu. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- Briggs, Derek; Crowther, Peter R. (2008). Palaeobiology II. John Wiley & Sons. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-470-99928-8.

- St. Fleur, Nicholas (16 February 2017). "After Earth's Worst Mass Extinction, Life Rebounded Rapidly, Fossils Suggest". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- Labandeira CC, Sepkoski JJ (1993). "Insect diversity in the fossil record" (PDF). Science. 261 (5119): 310–15. Bibcode:1993Sci...261..310L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.496.1576. doi:10.1126/science.11536548. PMID 11536548.

- McElwain, J.C.; Punyasena, S.W. (2007). "Mass extinction events and the plant fossil record". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 22 (10): 548–57. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.003. PMID 17919771.

- Sahney S.; Benton M.J. (2008). "Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1636): 759–65. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1370. PMC 2596898. PMID 18198148.

- Macleod, N.; Rawson, P. F.; Forey, P.L.; Banner, F.T.; Boudagher-Fadel, M.K.; Bown, P.R.; Burnett, J.A.; Chambers, P.; Culver, S.; Evans, S.E.; Jeffery, C.; Kaminski, M.A.; Lord, A.R.; Milner, A.C.; Milner, A.R.; Morris, N.; Owen, E.; Rosen, B.R.; Smith, A.B.; Taylor, P.D.; Urquhart, E.; Young, J.R. (April 1997). "The Cretaceous-Tertiary biotic transition". Journal of the Geological Society. 154 (2): 265–92. Bibcode:1997JGSoc.154..265M. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.154.2.0265.

- Raup, D.; Sepkoski Jr, J. (1982). "Mass extinctions in the marine fossil record". Science. 215 (4539): 1501–03. Bibcode:1982Sci...215.1501R. doi:10.1126/science.215.4539.1501. PMID 17788674.

- Fastovsky DE, Sheehan PM (2005). "The extinction of the dinosaurs in North America". GSA Today. 15 (3): 4–10. doi:10.1130/1052-5173(2005)15<4:TEOTDI>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1052-5173.

- McGhee, G.R.; Sheehan, P.M.; Bottjer, D.J.; Droser, M.L. (2011). "Ecological ranking of Phanerozoic biodiversity crises: The Serpukhovian (early Carboniferous) crisis had a greater ecological impact than the end-Ordovician". Geology. 40 (2): 147–50. Bibcode:2012Geo....40..147M. doi:10.1130/G32679.1.

- Sole, R.V., and Newman, M., 2002. "Extinctions and Biodiversity in the Fossil Record – Volume Two, The Earth system: biological and ecological dimensions of global environment change" pp. 297–391, Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change John Wilely & Sons.

- Smith, A.; A. McGowan (2005). "Cyclicity in the fossil record mirrors rock outcrop area". Biology Letters. 1 (4): 443–45. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0345. PMC 1626379. PMID 17148228.

- Smith, Andrew B.; McGowan, Alistair J. (2007). "The shape of the Phanerozoic marine palaeodiversity curve: How much can be predicted from the sedimentary rock record of Western Europe?". Palaeontology. 50 (4): 765–74. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00693.x.

- Malcolm L. McCallum (27 May 2015). "Vertebrate biodiversity losses point to a sixth mass extinction". Biodiversity and Conservation. 24 (10): 2497–519. doi:10.1007/s10531-015-0940-6.

- Pimm, S.L.; Jenkins, C.N.; Abell, R.; Brooks, T.M.; Gittleman, J. L.; Joppa, L.N.; Raven, P.H.; Roberts, C.M.; Sexton, J.O. (30 May 2014). "The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection". Science. 344 (6187): 1246752. doi:10.1126/science.1246752. PMID 24876501.

- "It's official: a global mass extinction is under way – JSTOR Daily". 3 July 2015.

- "We're Entering A Sixth Mass Extinction, And It's Our Fault".

- Sutter, John D. (July 11, 2017). "Sixth mass extinction: The era of 'biological annihilation'". CNN. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- Brondizio, Eduardo S.; Diaz, Sandra; Settele, Josef; Ngo, Hien (editors). (6 May 2019). Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES. p. 13. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- Watts, Jonathan (May 6, 2019). "Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life". The Guardian. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- Plumer, Brad (May 6, 2019). "Humans Are Speeding Extinction and Altering the Natural World at an 'Unprecedented' Pace". The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- Staff (May 6, 2019). "Media Release: Nature's Dangerous Decline 'Unprecedented'; Species Extinction Rates 'Accelerating'". Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- Benton, M.J. (2004). "6. Reptiles Of The Triassic". Vertebrate Palaeontology. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-04-566002-5.

- Van Valkenburgh, B. (1999). "Major patterns in the history of carnivorous mammals". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 27: 463–93. Bibcode:1999AREPS..27..463V. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.27.1.463.

- Jablonski, D. (2002). "Survival without recovery after mass extinctions". PNAS. 99 (12): 8139–44. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.8139J. doi:10.1073/pnas.102163299. PMC 123034. PMID 12060760.

- Budd, G.E.; Mann, R.P. (2018). "History is written by the victors: the effect of the push of the past on the fossil record". Evolution. 72 (11): 2276–91. doi:10.1111/evo.13593. PMC 6282550. PMID 30257040.

- Hallam, Anthony, & Wignall, P.B. (2002). Mass Extinctions and Their Aftermath. New York: Oxford University Press

- Beardsley, Tim (1988). "Star-struck?". Scientific American. 258 (4): 37–40. Bibcode:1988SciAm.258d..37B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0488-37b.

- Raup, DM; Sepkoski Jr, JJ (1984). "Periodicity of extinctions in the geologic past". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 81 (3): 801–05. Bibcode:1984PNAS...81..801R. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.3.801. PMC 344925. PMID 6583680.

- Different cycle lengths have been proposed; e.g. by Rohde, R.; Muller, R. (2005). "Cycles in fossil diversity". Nature. 434 (7030): 208–10. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..208R. doi:10.1038/nature03339. PMID 15758998.

- R.A. Muller. "Nemesis". Muller.lbl.gov. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- Adrian L. Melott; Richard K. Bambach (2010-07-02). "Nemesis Reconsidered". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- Gillman, Michael; Erenler, Hilary (2008). "The galactic cycle of extinction" (PDF). International Journal of Astrobiology. 7 (1): 17–26. Bibcode:2008IJAsB...7...17G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.384.9224. doi:10.1017/S1473550408004047. ISSN 1475-3006. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- Bailer-Jones, C.A.L. (July 2009). "The evidence for and against astronomical impacts on climate change and mass extinctions: a review". International Journal of Astrobiology. 8 (3): 213–219. arXiv:0905.3919. Bibcode:2009IJAsB...8..213B. doi:10.1017/S147355040999005X. ISSN 1475-3006.

- Overholt, A.C.; Melott, A.L.; Pohl, M. (2009). "Testing the link between terrestrial climate change and galactic spiral arm transit". The Astrophysical Journal. 705 (2): L101–03. arXiv:0906.2777. Bibcode:2009ApJ...705L.101O. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/705/2/L101.

- Melott, A.L.; Bambach, R.K. (2011). "A ubiquitous ~62-Myr periodic fluctuation superimposed on general trends in fossil biodiversity. I. Documentation". Paleobiology. 37: 92–112. arXiv:1005.4393. doi:10.1666/09054.1.

- Melott, A.L.; Bambach, Richard K.; Petersen, Kenni D.; McArthur, John M.; et al. (2012). "A ~60 Myr periodicity is common to marine-87Sr/86Sr, fossil biodiversity, and large-scale sedimentation: what does the periodicity reflect?". Journal of Geology. 120 (2): 217–26. arXiv:1206.1804. Bibcode:2012JG....120..217M. doi:10.1086/663877.

- Arens, N.C.; West, I.D. (2008). "Press-pulse: a general theory of mass extinction?". Paleobiology. 34 (4): 456–71. doi:10.1666/07034.1.

- Wang, S.C.; Bush, A.M. (2008). "Adjusting global extinction rates to account for taxonomic susceptibility". Paleobiology. 34 (4): 434–55. doi:10.1666/07060.1.

- Budd, G.E. (2003). "The Cambrian Fossil Record and the Origin of the Phyla". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 43 (1): 157–65. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.157. PMID 21680420.

- Martin, R.E. (1995). "Cyclic and secular variation in microfossil biomineralization: clues to the biogeochemical evolution of Phanerozoic oceans". Global and Planetary Change. 11 (1): 1–23. Bibcode:1995GPC....11....1M. doi:10.1016/0921-8181(94)00011-2.

- Martin, R.E. (1996). "Secular increase in nutrient levels through the Phanerozoic: Implications for productivity, biomass, and diversity of the marine biosphere". PALAIOS. 11 (3): 209–19. Bibcode:1996Palai..11..209M. doi:10.2307/3515230. JSTOR 3515230.

- Marshall, C.R.; Ward, P.D. (1996). "Sudden and Gradual Molluscan Extinctions in the Latest Cretaceous of Western European Tethys". Science. 274 (5291): 1360–63. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1360M. doi:10.1126/science.274.5291.1360. PMID 8910273.

- Arens, N.C. and West, I.D. (2006). "Press/Pulse: A General Theory of Mass Extinction?" 'GSA Conference paper' Abstract Archived 2017-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- MacLeod, N (2001-01-06). "Extinction!".

- Courtillot, V., Jaeger, J-J., Yang, Z., Féraud, G., Hofmann, C. (1996). "The influence of continental flood basalts on mass extinctions: where do we stand?" in Ryder, G., Fastovsky, D., and Gartner, S, eds. "The Cretaceous-Tertiary event and other catastrophes in earth history". The Geological Society of America, Special Paper 307, 513–525.

- Hallam, A. (1992). Phanerozoic sea-level changes. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07424-7.

- Grieve, R.; Rupert, J.; Smith, J.; Therriault, A. (1996). "The record of terrestrial impact cratering". GSA Today. 5: 193–95.

- The earliest known flood basalt event is the one which produced the Siberian Traps and is associated with the end-Permian extinction.

- Some of the extinctions associated with flood basalts and sea-level falls were significantly smaller than the "major" extinctions, but still much greater than the background extinction level.

- Wignall, P.B. (2001). "Large igneous provinces and mass extinctions". Earth-Science Reviews. 53 (1–2): 1–33. Bibcode:2001ESRv...53....1W. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(00)00037-4.

- Brannen, Peter (2017). The Ends of the World: Volcanic Apocalypses, Lethal Oceans, and Our Quest to Understand Earth's Past Mass Extinctions. Harper Collins. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-06-236480-7.

- http://www.nature.com/scientificamerican/journal/v263/n4/pdf/scientificamerican1090-85.pdf

- "Causes of the Cretaceous Extinction".

- Courtillot, V. (1994). "Mass extinctions in the last 300 million years: one impact and seven flood basalts?". Israel Journal of Earth Sciences. 43: 255–266.

- Courtillot, V.E., Renne, P.R., 2003. On the ages of flood basalt events. Comptes Rendus Geosciences 335 (1), 113–140.

- Kravchinsky, V. A. (2012). "Paleozoic large igneous provinces of Northern Eurasia: Correlation with mass extinction events" (PDF). Global and Planetary Change. 86: 31–36. Bibcode:2012GPC....86...31K. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.01.007.

- Peters, S.E. (June 15, 2008). "Environmental determinants of extinction selectivity in the fossil record". Nature. 454 (7204): 626–29. Bibcode:2008Natur.454..626P. doi:10.1038/nature07032. PMID 18552839.

- Newswise: Ebb and Flow of the Sea Drives World's Big Extinction Events Retrieved on June 15, 2008.

- Alvarez, Walter; Kauffman, Erle; Surlyk, Finn; Alvarez, Luis; Asaro, Frank; Michel, Helen (Mar 16, 1984). "Impact theory of mass extinctions and the invertebrate fossil record". Science. 223 (4641): 1135–41. Bibcode:1984Sci...223.1135A. doi:10.1126/science.223.4641.1135. JSTOR 1692570. PMID 17742919.

- Keller G, Abramovich S, Berner Z, Adatte T (1 January 2009). "Biotic effects of the Chicxulub impact, K–T catastrophe and sea level change in Texas". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 271 (1–2): 52–68. Bibcode:2009PPP...271...52K. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.09.007.

- Morgan J, Lana C, Kersley A, Coles B, Belcher C, Montanari S, Diaz-Martinez E, Barbosa A, Neumann V (2006). "Analyses of shocked quartz at the global K-P boundary indicate an origin from a single, high-angle, oblique impact at Chicxulub" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 251 (3–4): 264–79. Bibcode:2006E&PSL.251..264M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.09.009. hdl:10044/1/1208.

- Joel, Lucas (21 October 2019). "The Dinosaur-Killing Asteroid Acidified the Ocean in a Flash - The Chicxulub event was as damaging to life in the oceans as it was to creatures on land, a study shows". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Henehan, Michael J.; et al. (21 October 2019). "Rapid ocean acidification and protracted Earth system recovery followed the end-Cretaceous Chicxulub impact". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (45): 22500–22504. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11622500H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1905989116. PMC 6842625. PMID 31636204.

- Mayhew, Peter J.; Gareth B. Jenkins; Timothy G. Benton (January 7, 2008). "A long-term association between global temperature and biodiversity, origination and extinction in the fossil record". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1630): 47–53. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1302. PMC 2562410. PMID 17956842.

- Knoll, A.H.; Bambach, R.K.; Canfield, D.E.; Grotzinger, J.P. (26 July 1996). "Fossil record supports evidence of impending mass extinction". Science. 273 (5274): 452–457. Bibcode:1996Sci...273..452K. doi:10.1126/science.273.5274.452. PMID 8662528.

- Ward, Peter D.; Jennifer Botha; Roger Buick; Michiel O. De Kock; Douglas H. Erwin; Geoffrey H. Garrison; Joseph L. Kirschvink; Roger Smith (4 February 2005). "Abrupt and Gradual Extinction Among Late Permian Land Vertebrates in the Karoo Basin, South Africa". Science. 307 (5710): 709–714. Bibcode:2005Sci...307..709W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.503.2065. doi:10.1126/science.1107068. PMID 15661973.

- Kiehl, Jeffrey T.; Christine A. Shields (September 2005). "Climate simulation of the latest Permian: Implications for mass extinction". Geology. 33 (9): 757–760. Bibcode:2005Geo....33..757K. doi:10.1130/G21654.1.

- Hecht, J (2002-03-26). "Methane prime suspect for greatest mass extinction". New Scientist.

- Jenkyns, Hugh C. (2010-03-01). "Geochemistry of oceanic anoxic events". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 11 (3): Q03004. Bibcode:2010GGG....11.3004J. doi:10.1029/2009GC002788. ISSN 1525-2027.

- Long, J.; Large, R.R.; Lee, M.S.Y.; Benton, M. J.; Danyushevsky, L.V.; Chiappe, L.M.; Halpin, J.A.; Cantrill, D. & Lottermoser, B. (2015). "Severe Selenium depletion in the Phanerozoic oceans as a factor in three global mass extinction events". Gondwana Research. 36: 209–218. Bibcode:2016GondR..36..209L. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2015.10.001. hdl:1983/68e97709-15fb-496b-b28d-f8ea9ea9b4fc.

- Watson, Andrew J. (2016-12-23). "Oceans on the edge of anoxia". Science. 354 (6319): 1529–1530. Bibcode:2016Sci...354.1529W. doi:10.1126/science.aaj2321. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28008026.

- Berner, R.A., and Ward, P.D. (2004). "Positive Reinforcement, H2S, and the Permo-Triassic Extinction: Comment and Reply" describes possible positive feedback loops in the catastrophic release of hydrogen sulfide proposed by Kump, Pavlov and Arthur (2005).

- Kump, L.R.; Pavlov, A.; Arthur, M.A. (2005). "Massive release of hydrogen sulfide to the surface ocean and atmosphere during intervals of oceanic anoxia". Geology. 33 (5): 397–400. Bibcode:2005Geo....33..397K. doi:10.1130/g21295.1. Summarised by Ward (2006).

- Ward, P.D. (2006). "Impact from the Deep". Scientific American. 295 (4): 64–71. Bibcode:2006SciAm.295d..64W. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1006-64. PMID 16989482.

- Wilde, P; Berry, W.B.N. (1984). "Destabilization of the oceanic density structure and its significance to marine "extinction" events". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 48 (2–4): 143–62. Bibcode:1984PPP....48..143W. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(84)90041-5.

- Corey S. Powell (2001-10-01). "20 Ways the World Could End". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- Podsiadlowski, Ph.; et al. (2004). "The Rates of Hypernovae and Gamma-Ray Bursts: Implications for Their Progenitors". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 607 (1): L17. arXiv:astro-ph/0403399. Bibcode:2004ApJ...607L..17P. doi:10.1086/421347.

- Melott, A.L.; Thomas, B.C. (2009). "Late Ordovician geographic patterns of extinction compared with simulations of astrophysical ionizing radiation damage". Paleobiology. 35 (3): 311–20. arXiv:0809.0899. doi:10.1666/0094-8373-35.3.311.

- Wei, Yong; Pu, Zuyin; Zong, Qiugang; Wan, Weixing; Ren, Zhipeng; Fraenz, Markus; Dubinin, Eduard; Tian, Feng; Shi, Quanqi; Fu, Suiyan; Hong, Minghua (1 May 2014). "Oxygen escape from the Earth during geomagnetic reversals: Implications to mass extinction". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 394: 94–98. Bibcode:2014E&PSL.394...94W. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.03.018 – via NASA ADS.

- "Speculated Causes of the Permian Extinction". Hooper Virtual Paleontological Museum. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dirzo, Rodolfo (2017-07-10). "Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (30): E6089–E6096. doi:10.1073/pnas.1704949114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5544311. PMID 28696295.

- Franck, S; Bounama, C; von Bloh, W (2006). "Causes and Timing of Future Biosphere Extinction" (PDF). Biogeosciences. 3 (1): 85–92. Bibcode:2006BGeo....3...85F. doi:10.5194/bg-3-85-2006.

-

Ward, Peter; Brownlee, Donald (December 2003). The Life and Death of Planet Earth: How the New Science of Astrobiology Charts the Ultimate Fate of Our World (Google Books). Henry Holt and Co. pp. 132, 139, 141. ISBN 978-0-8050-7512-0.

moist greenhouse effect

- David Quammen (October 1998). "Planet of Weeds" (PDF). Harper's Magazine. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- "Evolution imposes 'speed limit' on recovery after mass extinctions". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- Lehrmann; D.J.; Ramezan; J.; Bowring; S.A.; et al. (December 2006). "Timing of recovery from the end-Permian extinction: Geochronologic and biostratigraphic constraints from south China". Geology. 34 (12): 1053–1056. Bibcode:2006Geo....34.1053L. doi:10.1130/G22827A.1.

- Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J. (2008). "Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1636): 759–65. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1370. PMC 2596898. PMID 18198148.

- Sidor, C. A.; Vilhena, D. A.; Angielczyk, K. D.; Huttenlocker, A. K.; Nesbitt, S. J.; Peecook, B. R.; Steyer, J. S.; Smith, R. M. H.; Tsuji, L. A. (2013). "Provincialization of terrestrial faunas following the end-Permian mass extinction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (20): 8129–8133. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.8129S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1302323110. PMC 3657826. PMID 23630295.

- Cascales-Miñana, B.; Cleal, C. J. (2011). "Plant fossil record and survival analyses". Lethaia. 45: 71–82. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2011.00262.x.

External links

- Calculate the effects of an Impact

- Species Alliance (nonprofit organization producing a documentary about Mass Extinction titled "Call of Life: Facing the Mass Extinction)

- Interstellar Dust Cloud-induced Extinction Theory

- Sepkoski's Global Genus Database of Marine Animals – Calculate extinction rates for yourself!