Woodrow Wilson

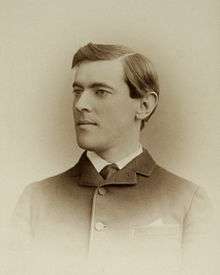

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856 – February 3, 1924) was an American politician, lawyer, and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of Princeton University and as the 34th governor of New Jersey before winning the 1912 presidential election. As president, he oversaw the passage of progressive legislative policies unparalleled until the New Deal in 1933. He also led the United States into World War I in 1917, establishing an activist foreign policy known as "Wilsonianism." He was the leading architect of the League of Nations.

Woodrow Wilson | |

|---|---|

Wilson in 1919 | |

| 28th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1913 – March 4, 1921 | |

| Vice President | Thomas R. Marshall |

| Preceded by | William Howard Taft |

| Succeeded by | Warren G. Harding |

| 34th Governor of New Jersey | |

| In office January 17, 1911 – March 1, 1913 | |

| Preceded by | John Franklin Fort |

| Succeeded by | James Fairman Fielder (acting) |

| 13th President of Princeton University | |

| In office October 25, 1902 – October 21, 1910 | |

| Preceded by | Francis Patton |

| Succeeded by | John Aikman Stewart (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thomas Woodrow Wilson December 28, 1856 Staunton, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | February 3, 1924 (aged 67) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Washington National Cathedral |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Margaret Jessie Eleanor |

| Relatives | Joseph Ruggles Wilson (father) |

| Education | Davidson College Princeton University (AB) University of Virginia Johns Hopkins University (MA, PhD) |

| Awards | Nobel Peace Prize |

| Signature |  |

| ||

|---|---|---|

President of the United States

First term

Second term

|

||

Wilson spent his early years in the American South (mainly in Augusta, Georgia) during the Civil War and Reconstruction. After earning a Ph.D. in political science from Johns Hopkins University, Wilson taught at various schools before becoming the president of Princeton University. As governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913, Wilson broke with party bosses and won the passage of several progressive reforms. His success in New Jersey gave him a national reputation as a progressive reformer, and he won the presidential nomination at the 1912 Democratic National Convention. Wilson defeated incumbent Republican President William Howard Taft and Progressive Party nominee former president Theodore Roosevelt to win the 1912 presidential election, becoming the first Southerner to be elected president since the American Civil War.

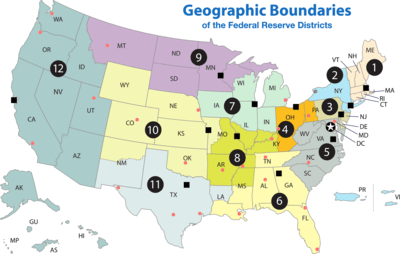

During his first term, Wilson presided over the passage of his progressive New Freedom domestic agenda. His first major priority was the passage of the Revenue Act of 1913, which lowered tariffs and implemented a federal income tax. Later tax acts implemented a federal estate tax and raised the top income tax rate to 77 percent. Wilson also presided over the passage of the Federal Reserve Act, which created a central banking system in the form of the Federal Reserve System. Two major laws, the Federal Trade Commission Act and the Clayton Antitrust Act, were passed to regulate and break up large business interests known as trusts. To the disappointment of his African-American supporters, Wilson allowed some of his Cabinet members to segregate their departments. Upon the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Wilson maintained a policy of neutrality between the Allied Powers and the Central Powers. He won re-election by a narrow margin in the presidential election of 1916, defeating Republican nominee Charles Evans Hughes.

In early 1917, Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against the German Empire after it implemented a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, and Congress complied. Wilson presided over war-time mobilization but devoted much of his efforts to foreign affairs, developing the Fourteen Points as a basis for post-war peace. After Germany signed an armistice in November 1918, Wilson and other Allied leaders took part in the Paris Peace Conference, where Wilson advocated for the establishment of a multilateral organization, per his "fourteenth point". The resulting League of Nations was incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles and other treaties with the defeated Central Powers, but Wilson was subsequently unable to convince the Senate to ratify that treaty or allow the United States to join the League. Wilson suffered a severe stroke in October 1919 and was incapacitated for the remainder of his presidency. He retired from public office in 1921 and died in 1924. Scholars have generally ranked Wilson as one of the better U.S. presidents,[1][2] though he has received strong criticism for being an exponent of racial segregation and white supremacy.[3][4]

Early life

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was born to a family of Scots-Irish and Scottish descent, in Staunton, Virginia, on December 28, 1856.[5] He was the third of four children and the first son of Joseph Ruggles Wilson (1822–1903) and Jessie Janet Woodrow (1826–1888), growing up in a home where slave labour was utilised.[6] Wilson's paternal grandparents had immigrated to the United States from Strabane, County Tyrone, Ireland in 1807, settling in Steubenville, Ohio. His grandfather James Wilson published a pro-tariff and anti-slavery newspaper, The Western Herald and Gazette.[7] Wilson's maternal grandfather, Reverend Thomas Wodrow, migrated from Paisley, Scotland to Carlisle, England, before moving to Chillicothe, Ohio in the late 1830s.[8] Joseph met Jessie while she was attending a girl's academy in Steubenville, and the two married on June 7, 1849. Soon after the wedding, Joseph was ordained as a Presbyterian pastor and assigned to serve in Staunton.[9] He was born in The Manse, a house of the Staunton First Presbyterian Church where Joseph served. Wilson's parents gave him the nickname "Tommy", which he used until he was 16. Before he was two, the family moved to Augusta, Georgia.[10]

.jpg)

Wilson's earliest memory was of playing in his yard and standing near the front gate of the Augusta parsonage at the age of three, when he heard a passerby announce in disgust that Abraham Lincoln had been elected and that a war was coming.[10][11] By 1861, both of Wilson's parents had come to fully identify with the Southern United States and they supported the Confederacy during the American Civil War.[12] Wilson's father was one of the founders of the Southern Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) after it split from the Northern Presbyterians in 1861.

He became minister of the First Presbyterian Church in Augusta, and the family lived there until 1870.[13] After the end of the Civil War, Wilson began attending a nearby school, where classmates included future Supreme Court Justice Joseph Rucker Lamar and future ambassador Pleasant A. Stovall.[14] Though Wilson's parents placed a high value on education, he struggled with reading and writing until the age of thirteen, possibly because of developmental dyslexia.[15] From 1870 to 1874, Wilson lived in Columbia, South Carolina, where his father was a theology professor at the Columbia Theological Seminary.[16] In 1873, Wilson became a communicant member of the Columbia First Presbyterian Church; he remained a member throughout his life.[17]

Wilson attended Davidson College in North Carolina for the 1873–74 school year, but transferred as a freshman to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University).[18] He studied political philosophy and history, joined the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity, was active in the Whig literary and debating society, and organized the Liberal Debating Society.[19] He was also elected secretary of the school's football association, president of the school's baseball association, and managing editor of the student newspaper.[20] In the hotly contested presidential election of 1876, Wilson declared his support for the Democratic Party and its nominee, Samuel J. Tilden.[21] Influenced by the work of Walter Bagehot, as well as the declining power of the presidency in the aftermath of the Civil War, Wilson developed a plan to reform American government along the lines of the British parliamentary system.[22] Political scientist George W. Ruiz writes that Wilson's "admiration for the parliamentary style of government, and the desire to adapt some of its features to the American system, remained an enduring element of Woodrow Wilson's political thought."[23] Wilson's essay on governmental reform was published in the International Review after winning the approval of editor Henry Cabot Lodge.[22]

After graduating from Princeton in 1879,[24] Wilson attended the University of Virginia School of Law, where he was involved in the Virginia Glee Club and served as president of the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society.[25] After poor health forced his withdrawal from the University of Virginia, Wilson continued to study law on his own while living with his parents in Wilmington, North Carolina.[26] Wilson was admitted to the Georgia bar and made a brief attempt at establishing a legal practice in Atlanta in 1882.[27] Though he found legal history and substantive jurisprudence interesting, he abhorred the day-to-day procedural aspects. After less than a year, he abandoned his legal practice to pursue the study of political science and history.[28]

Marriage and family

In 1883, Wilson met and fell in love with Ellen Louise Axson, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister from Savannah, Georgia.[29] He proposed marriage in September 1883; she accepted, but they agreed to postpone marriage while Wilson attended graduate school.[30] Wilson's marriage to Ellen was complicated by traumatic developments in her family; in late 1883, Ellen's father Edward, suffering from depression, was admitted to the Georgia State Mental Hospital, where in 1884 he committed suicide. After recovering from the initial shock, Ellen gained admission to the Art Students League of New York. After graduation, she pursued portrait art and received a medal for one of her works from the Paris International Exposition. She happily agreed to sacrifice further independent artistic pursuits in order to keep her marriage commitment, and in 1885 she and Wilson married.[31] She strongly supported his career, and learned German so that she could help translate works of political science that were relevant to Wilson's research.[32]

Their first child, Margaret, was born in April 1886, and their second child, Jessie, was born in August 1887.[33] Their third and final child, Eleanor, was born in October 1889.[34] Wilson and his family lived in a seven bedroom Tudor Revival house near Princeton, New Jersey from 1896 to 1902, when they moved to Prospect House on Princeton's campus.[35] In 1913, Jessie married Francis Bowes Sayre Sr., who later served as High Commissioner to the Philippines.[36] In 1914, Eleanor married William Gibbs McAdoo, who served as the Secretary of the Treasury under Wilson and later represented California in the United States Senate.[37]

Academic career

Professor

In late 1883, Wilson entered Johns Hopkins University, a new graduate institution in Baltimore modeled after German universities.[38] Wilson hoped to become a professor, writing that "a professorship was the only feasible place for me, the only place that would afford leisure for reading and for original work, the only strictly literary berth with an income attached."[39] During his time at Johns Hopkins, Wilson took courses by eminent scholars such as Herbert Baxter Adams, Richard T. Ely, and J. Franklin Jameson.[40] Wilson spent much of his time at Johns Hopkins writing Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics, which grew out of a series of essays in which he examined the workings of the federal government.[41] He received a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins in 1886.[42]

In early 1885, Houghton Mifflin published Congressional Government, which received a strong reception; one critic called it "the best critical writing on the American constitution which has appeared since the Federalist Papers." That same year, Wilson accepted a teaching position at Bryn Mawr College, a newly-established women's college on the Philadelphia Main Line.[43] Wilson taught at Bryn Mawr College from 1885 until 1888.[44] He taught ancient Greek and Roman history, American history, political science, and other subjects. He sought to inspire "genuine living interest in the subjects of study" and asked students to "look into ancient times as if they were our own times."[45] In 1888, Wilson left Bryn Mawr for Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.[46] At Wesleyan he coached the football team, founded a debate team,[47] and taught graduate courses in political economy and Western history.[48]

In February 1890, with the help of friends, Wilson was elected by the Princeton University Board of Trustees to the Chair of Jurisprudence and Political Economy, at an annual salary of $3,000 (equivalent to $85,367 in 2019).[49] He quickly gained a reputation as a compelling speaker; one student described him as "the greatest class-room lecturer I ever have heard."[50] During his time as a professor at Princeton, he also delivered a series of lectures at Johns Hopkins, New York Law School, and Colorado College.[51] In 1896, Francis Landey Patton announced that Princeton would henceforth officially be known as Princeton University instead of the College of New Jersey, and he unveiled an ambitious program of expansion that included the establishment of a graduate school.[52] In the 1896 presidential election, Wilson rejected Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan and supported the conservative "Gold Democrat" nominee, John M. Palmer.[53] Wilson's academic reputation continued to grow throughout the 1890s, and he turned down positions at Johns Hopkins, the University of Virginia, and other schools because he wanted to remain at Princeton.[54]

Author

During his academic career, Wilson authored several works of history and political science and became a regular contributor to Political Science Quarterly, an academic journal.[55] Wilson's first political work, Congressional Government (1885), critically described the U.S. system of government and advocated adopting reforms to move the U.S. closer to a parliamentary system.[56] Wilson believed the Constitution had a "radical defect" because it did not establish a branch of government that could "decide at once and with conclusive authority what shall be done."[57] He singled out the United States House of Representatives for particular criticism, writing,

divided up, as it were, into forty-seven seignories, in each of which a standing committee is the court-baron and its chairman lord-proprietor. These petty barons, some of them not a little powerful, but none of them within reach [of] the full powers of rule, may at will exercise an almost despotic sway within their own shires, and may sometimes threaten to convulse even the realm itself.[58]

Wilson's second publication was a textbook, entitled The State, that was used widely in college courses throughout the country until the 1920s.[59] In The State, Wilson wrote that governments could legitimately promote the general welfare "by forbidding child labor, by supervising the sanitary conditions of factories, by limiting the employment of women in occupations hurtful to their health, by instituting official tests of the purity or the quality of goods sold, by limiting the hours of labor in certain trades, [and] by a hundred and one limitations of the power of unscrupulous or heartless men to out-do the scrupulous and merciful in trade or industry."[60] He also wrote that charity efforts should be removed from the private domain and "made the imperative legal duty of the whole," a position which, according to historian Robert M. Saunders, seemed to indicate that Wilson "was laying the groundwork for the modern welfare state."[61]

His third book, entitled Division and Reunion, was published in 1893.[62] It became a standard university textbook for teaching mid- and late-19th century U.S. history.[51] In 1897, Houghton Mifflin published Wilson's biography on George Washington; Berg describes it as "Wilson's poorest literary effort."[63] Wilson's fourth major publication, a five-volume work entitled History of the American People, was the culmination of a series of articles written for Harper's, and was published in 1902.[64] In 1908, Wilson published his last major scholarly work, Constitutional Government of the United States.[65]

President of Princeton University

In June 1902, Princeton trustees promoted Professor Wilson to president, replacing Patton, whom the trustees perceived to be an inefficient administrator.[66] Wilson aspired, as he told alumni, "to transform thoughtless boys performing tasks into thinking men." He tried to raise admission standards and to replace the "gentleman's C" with serious study. To emphasize the development of expertise, Wilson instituted academic departments and a system of core requirements. Students were to meet in groups of six under the guidance of teaching assistants known as preceptors.[67] To fund these new programs, Wilson undertook an ambitious and successful fundraising campaign, convincing alumni such as Moses Taylor Pyne and philanthropists such as Andrew Carnegie to donate to the school.[68] Wilson appointed the first Jew and the first Roman Catholic to the faculty, and helped liberate the board from domination by conservative Presbyterians.[69] He also worked to keep African Americans out of the school, even as other Ivy League schools were accepting small numbers of blacks.[70][lower-alpha 1]

Wilson's efforts to reform Princeton earned him national notoriety, but they also took a toll on his health.[72] In 1906, Wilson awoke to find himself blind in the left eye, the result of a blood clot and hypertension. Modern medical opinion surmises Wilson had suffered a stroke—he later was diagnosed, as his father had been, with hardening of the arteries. He began to exhibit his father's traits of impatience and intolerance, which would on occasion lead to errors of judgment.[73] When Wilson began vacationing in Bermuda in 1906, he met a socialite, Mary Hulbert Peck. Their visits together became a regular occurrence on his return. Wilson in his letters home to Ellen openly related these gatherings as well his other social events. According to biographer August Heckscher, Wilson's friendship with Peck became the topic of frank discussion between Wilson and his wife. Wilson historians have not conclusively established there was an affair; but Wilson did on one occasion write a musing in shorthand—on the reverse side of a draft for an editorial: "my precious one, my beloved Mary."[74] Wilson also sent very personal letters to her which would later be used against him by his adversaries.[75]

Having reorganized the school's curriculum and established the preceptorial system, Wilson next attempted to curtail the influence of social elites at Princeton by abolishing the upper-class eating clubs.[76] He proposed moving the students into colleges, also known as quadrangles, but Wilson's Quad Plan was met with fierce opposition from Princeton's alumni.[77] In October 1907, due to the intensity of alumni opposition, the Board of Trustees instructed Wilson to withdraw the Quad Plan.[78] Late in his tenure, Wilson had a confrontation with Andrew Fleming West, dean of the graduate school, and also West's ally ex-President Grover Cleveland, who was a trustee. Wilson wanted to integrate a proposed graduate school building into the campus core, while West preferred a more distant campus site. In 1909, Princeton's board accepted a gift made to the graduate school campaign subject to the graduate school being located off campus.[79]

Wilson became disenchanted with his job due to the resistance to his recommendations, and he began considering a run for office. Prior to the 1908 Democratic National Convention, Wilson dropped hints to some influential players in the Democratic Party of his interest in the ticket. While he had no real expectations of being placed on the ticket, he left instructions that he should not be offered the vice presidential nomination. Party regulars considered his ideas politically as well as geographically detached and fanciful, but the seeds had been sown.[80] McGeorge Bundy in 1956 described Wilson's contribution to Princeton: "Wilson was right in his conviction that Princeton must be more than a wonderfully pleasant and decent home for nice young men; it has been more ever since his time".[81]

Governor of New Jersey (1911−1913)

By January 1910, Wilson had drawn the attention of James Smith, Jr. and George Brinton McClellan Harvey, two leaders of New Jersey's Democratic Party, as a potential candidate in the upcoming gubernatorial election.[82] Having lost the last five gubernatorial elections, New Jersey Democratic leaders decided to throw their support behind Wilson, an untested and unconventional candidate. Party leaders believed that Wilson's academic reputation made him the ideal spokesman against trusts and corruption, but they also hoped his inexperience in governing would make him easy to influence.[83] Wilson agreed to accept the nomination if "it came to me unsought, unanimously, and without pledges to anybody about anything."[84]

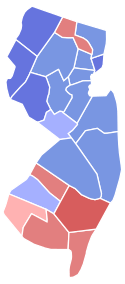

At the state party convention, the bosses marshaled their forces and won the nomination for Wilson. He submitted his letter of resignation to Princeton on October 20.[85] Wilson's campaign focused on his promise to be independent of party bosses. He quickly shed his professorial style for more emboldened speechmaking and presented himself as a full-fledged progressive.[86] Though Republican William Howard Taft had carried New Jersey in the 1908 presidential election by more than 82,000 votes, Wilson soundly defeated Republican gubernatorial nominee Vivian M. Lewis by a margin of more than 65,000 votes.[87] Democrats also took control of the general assembly in the 1910 elections, though the state senate remained in Republican hands.[88] After winning the election, Wilson appointed Joseph Patrick Tumulty as his private secretary, a position he would hold throughout Wilson's political career.[88]

Wilson began formulating his reformist agenda, intending to ignore the demands of his party machinery. Smith asked Wilson to endorse his bid for the U.S. Senate, but Wilson refused and instead endorsed Smith's opponent James Edgar Martine, who had won the Democratic primary. Martine's victory in the Senate election helped Wilson position himself as an independent force in the New Jersey Democratic Party.[89] By the time Wilson took office, New Jersey had gained a reputation for public corruption; the state was known as the "Mother of Trusts" because it allowed companies like Standard Oil to escape the antitrust laws of other states.[90] Wilson and his allies quickly won passage of the Geran bill, which undercut the power of the political bosses by requiring primaries for all elective offices and party officials. A corrupt practices law and a workmen's compensation statute that Wilson supported won passage shortly thereafter.[91] For his success in passing these laws during the first months of his gubernatorial term, Wilson won national and bipartisan recognition as a reformer and a leader of the Progressive movement.[92]

Wilson's legislative assault against party leaders split the state party and earned the enmity of Smith and others. Republicans took control of the state assembly in early 1912, and Wilson spent much of the rest of his tenure vetoing bills.[93] Nonetheless, he won passage of laws that restricted labor by women and children and increased standards for factory working conditions.[94] A new State Board of Education was set up "with the power to conduct inspections and enforce standards, regulate districts' borrowing authority, and require special classes for students with handicaps."[95] Shortly before leaving office, Wilson signed a series of antitrust laws known as the "Seven Sisters," as well as another law that removed the power to select juries from local sheriffs.[96]

Presidential election of 1912

Democratic nomination

Wilson became a prominent 1912 presidential contender immediately upon his election as Governor of New Jersey in 1910, and his clashes with state party bosses enhanced his reputation with the rising Progressive movement.[97] In addition to progressives, Wilson enjoyed the support of Princeton alumni such as Cyrus McCormick and Southerners such as Walter Hines Page, who believed that Wilson's status as a transplanted Southerner gave him broad appeal.[98] Though Wilson's shift to the left won the admiration of many, it also created enemies such as George Brinton McClellan Harvey, a former Wilson supporter who had close ties to Wall Street.[99] In July 1911, Wilson brought William Gibbs McAdoo and "Colonel" Edward M. House in to manage the campaign.[100] Prior to the 1912 Democratic National Convention, Wilson made a special effort to win the approval of three-time Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan, whose followers had largely dominated the Democratic Party since the 1896 presidential election.[101]

Speaker of the House Champ Clark of Missouri was viewed by many as the front-runner for the nomination, while House Majority Leader Oscar Underwood of Alabama also loomed as a challenger. Clark found support among the Bryan wing of the party, while Underwood appealed to the conservative Bourbon Democrats, especially in the South.[102] In the 1912 Democratic Party presidential primaries, Clark won several of the early contests, but Wilson finished strong with victories in Texas, the Northeast, and the Midwest.[103] On the first presidential ballot of the Democratic convention, Clark won a plurality of delegates; his support continued to grow after the New York Tammany Hall machine swung behind him on the tenth ballot.[104] Tammany's support backfired for Clark, as Bryan announced that he would not support any candidate that had Tammany's backing, and Clark began losing delegates on subsequent ballots.[105] The Wilson campaign picked up additional delegates by promising the vice presidency to Governor Thomas R. Marshall of Indiana, and several Southern delegations shifted their support from Underwood to Wilson. Wilson finally won two-thirds of the vote on the convention's 46th ballot, and Marshall became Wilson's running mate.[106]

General election

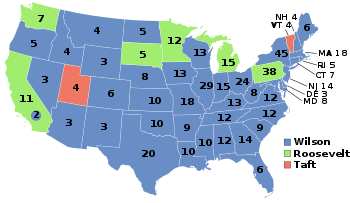

Wilson faced two major opponents in the 1912 general election: one-term Republican incumbent William Howard Taft, and former Republican President Theodore Roosevelt, who ran a third party campaign as the "Bull Moose" Party nominee. A fourth candidate was Eugene V. Debs of the Socialist Party. Roosevelt had broken with his former party at the 1912 Republican National Convention after Taft narrowly won re-nomination, and the split in the Republican Party made Democrats hopeful that they could win the presidency for the first time since the 1892 presidential election.[107]

Roosevelt emerged as Wilson's main challenger, and Wilson and Roosevelt largely campaigned against each other despite sharing similarly progressive platforms that called for an interventionist central government.[108] Wilson directed campaign finance chairman Henry Morgenthau not to accept contributions from corporations and to prioritize smaller donations from the widest possible quarters of the public.[109] During the election campaign, Wilson asserted that it was the task of government "to make those adjustments of life which will put every man in a position to claim his normal rights as a living, human being."[110] With the help of legal scholar Louis D. Brandeis, he developed his New Freedom platform, focusing especially on breaking up trusts and lowering tariff rates.[111] Brandeis and Wilson rejected Roosevelt's proposal to establish a powerful bureaucracy charged with regulating large corporations, instead favoring the break-up of large corporations in order to create a level economic playing field.[112]

Wilson engaged in a spirited campaign, criss-crossing the country to deliver numerous speeches.[113] Ultimately, he took 42 percent of the popular vote and 435 of the 531 electoral votes.[114] Roosevelt won most of the remaining electoral votes and 27.4 percent of the popular vote, one of the strongest third party performances in U.S. history. Taft won 23.2 percent of the popular vote but just 8 electoral votes, while Debs won 6 percent of the popular vote. In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats retained control of the House and won a majority in the Senate.[115] Wilson's victory made him the first Southerner to win a presidential election since the Civil War, the first Democratic president since Grover Cleveland left office in 1897,[116] and the first president to hold a Ph.D.[117]

Presidency (1913−1921)

| The Wilson Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Woodrow Wilson | 1913–1921 |

| Vice President | Thomas R. Marshall | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of State | William J. Bryan | 1913–1915 |

| Robert Lansing | 1915–1920 | |

| Bainbridge Colby | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | William G. McAdoo | 1913–1918 |

| Carter Glass | 1918–1920 | |

| David F. Houston | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of War | Lindley M. Garrison | 1913–1916 |

| Newton D. Baker | 1916–1921 | |

| Attorney General | James C. McReynolds | 1913–1914 |

| Thomas W. Gregory | 1914–1919 | |

| A. Mitchell Palmer | 1919–1921 | |

| Postmaster General | Albert S. Burleson | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Josephus Daniels | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Franklin K. Lane | 1913–1920 |

| John B. Payne | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | David F. Houston | 1913–1920 |

| Edwin T. Meredith | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Commerce | William C. Redfield | 1913–1919 |

| Joshua W. Alexander | 1919–1921 | |

| Secretary of Labor | William B. Wilson | 1913–1921 |

After the election, Wilson chose William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State, and Bryan offered advice on the remaining members of Wilson's cabinet.[118] William Gibbs McAdoo, a prominent Wilson supporter who would marry Wilson's daughter in 1914, became Secretary of the Treasury, and James Clark McReynolds, who had successfully prosecuted several prominent antitrust cases, was chosen as Attorney General.[119] Progressive North Carolina attorney Josephus Daniels became Secretary of the Navy, while young New York attorney Franklin D. Roosevelt became Assistant Secretary of the Navy.[120] Wilson's chief of staff ("secretary") was Joseph Patrick Tumulty, who acted as a political buffer and intermediary with the press.[121] The most important foreign policy adviser and confidant was "Colonel" Edward M. House; Berg writes that, "in access and influence, [House] outranked everybody in Wilson's Cabinet."[122]

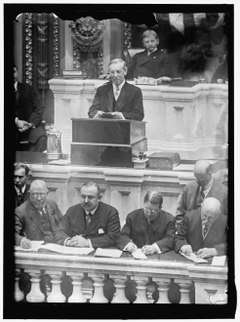

New Freedom domestic agenda

Wilson introduced a comprehensive program of domestic legislation at the outset of his administration, something no president had ever done before.[124] He had four major domestic priorities: the conservation of natural resources, banking reform, tariff reduction, and equal access to raw materials, which would be accomplished in part through the regulation of trusts.[125] Wilson introduced these proposals in April 1913 in a speech delivered to a joint session of Congress, becoming the first president since John Adams to address Congress in person.[126][lower-alpha 2] Though foreign affairs would increasingly dominate his presidency starting in 1915, Wilson's first two years in office largely focused on the implementation of his New Freedom domestic agenda.[128]

Tariff and tax legislation

Democrats had long seen high tariff rates as equivalent to unfair taxes on consumers, and tariff reduction was President Wilson's first priority.[129] He argued that the system of high tariffs "cuts us off from our proper part in the commerce of the world, violates the just principles of taxation, and makes the government a facile instrument in the hands of private interests."[130] Shortly before Wilson took office, the Sixteenth Amendment, which authorized Congress to impose an income tax without apportioning the tax among the states, was ratified by the requisite number of states.[131] By late May 1913, House Majority Leader Oscar Underwood had passed a bill in the House that cut the average tariff rate by 10 percent and imposed a tax on personal income above $4,000.[132] Underwood's bill, which represented the largest downward revision of the tariff since the Civil War, aggressively cut rates for raw materials, goods deemed to be "necessities," and products produced domestically by trusts, but it retained higher tariff rates for luxury goods.[133]

Passage of Underwood's tariff bill in the Senate would prove more difficult than in the House, partially because some Southern and Western Democrats favored the continued protection of the wool and sugar industries, and partially because Democrats had a narrower majority in that chamber.[129] Seeking to marshal support for the tariff bill, Wilson met extensively with Democratic senators and appealed directly to the people through the press. After weeks of hearings and debate, Wilson and Secretary of State Bryan managed to unite Senate Democrats behind the bill.[132] The Senate voted 44 to 37 in favor of the bill, with only one Democrat voting against it and only one Republican, progressive leader Robert M. La Follette, voting for it. Wilson signed the Revenue Act of 1913 (also known as the Underwood Tariff) into law on October 3, 1913.[132]

The Revenue Act of 1913 reduced the average import tariff rates from approximately 40 percent to approximately 26 percent[134] and restored a federal income tax for the first time since 1872.[lower-alpha 3] The Revenue Act of 1913 imposed a one percent tax on incomes above $3,000, affecting approximately three percent of the population.[135] Congress later passed the Revenue Act of 1916, which reinstated the federal estate tax, established a tax on the production of munitions, raised the top income tax rate to fifteen percent, and raised the corporate income tax from one percent to two percent.[136] The policies of the Wilson administration had a durable impact on the composition of government revenue, which after the 1920s would primarily come from taxation rather than tariffs.[137]

Federal Reserve System

Wilson did not wait to complete the Revenue Act of 1913 before proceeding to the next item on his agenda—banking. By the time Wilson took office, countries like Britain and Germany had established government-run central banks, but the United States had not had a central bank since the Bank War of the 1830s.[138] In the aftermath of the Panic of 1907, there was general agreement among leaders in both parties of the necessity to create some sort of central banking system to provide a more elastic currency and to coordinate responses to financial panics. Wilson sought a middle ground between progressives such as Bryan and conservative Republicans like Nelson Aldrich, who, as chairman of the National Monetary Commission, had put forward a plan for a central bank that would give private financial interests a large degree of control over the monetary system.[139] Wilson declared that the banking system must be "public not private, [and] must be vested in the government itself so that the banks must be the instruments, not the masters, of business."[140]

Democratic Congressmen Carter Glass and Robert L. Owen crafted a compromise plan in which private banks would control twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, but a controlling interest in the system was placed in a central board filled with presidential appointees. Wilson convinced Bryan's supporters that the plan met their demands for an elastic currency because Federal Reserve notes would be obligations of the government.[141] The bill passed the House in September 1913, but it faced stronger opposition in the Senate. After Wilson convinced just enough Democrats to defeat an amendment put forth by bank president Frank A. Vanderlip that would have given private banks greater control over the central banking system, the Senate voted 54–34 to approve the Federal Reserve Act.[142] The new system began operations in 1915, and it played an important role in financing the Allied and American war effort in World War I.[143]

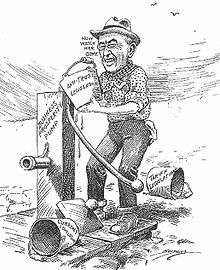

Antitrust legislation

Having passed major legislation lowering the tariff and reforming the banking structure, Wilson next sought antitrust legislation to enhance the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.[144] The Sherman Antitrust Act barred any "contract, combination...or conspiracy, in restraint of trade," but had proved ineffective in preventing the rise of large business combinations known as trusts.[145] An elite group of businessmen dominated the boards of major banks and railroads, and they used their power to prevent competition by new companies.[146] With Wilson's support, Congressman Henry Clayton, Jr. introduced a bill that would ban several anti-competitive practices such discriminatory pricing, tying, exclusive dealing, and interlocking directorates.[147] As the difficulty of banning all anti-competitive practices via legislation became clear, Wilson came to back legislation that would create a new agency, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), to investigate antitrust violations and enforce antitrust laws independently of the Justice Department. With bipartisan support, Congress passed the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, which incorporated Wilson's ideas regarding the FTC.[148] One month after signing the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, Wilson signed the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which built on the Sherman Act by defining and banning several anti-competitive practices.[149]

Labor and agriculture

.jpg)

Wilson's labor policy focused on using the Labor Department to mediate conflicts between labor and management.[150] In 1914, Wilson dispatched soldiers to help bring an end to the Colorado Coalfield War, one of the deadliest labor disputes in U.S. history.[151] In mid-1916, after a major railroad strike endangered the nation's economy, Wilson called the parties to a White House summit.[152] Wilson convinced both sides to put the strike on hold while he pushed Congress to pass a law providing for an eight-hour work day for railroad workers.[153] After Congress passed the Adamson Act, which incorporated the president's proposed eight-hour work day, the strike was cancelled. Wilson was widely praised for averting a national economic disaster, but conservatives denounced the law as a sellout to the unions and a surrender by Congress to an imperious president.[152] The Adamson Act was the first federal law that regulated hours worked by private employees.[154]

Secretary of Agriculture David F. Houston worked with Congressman Asbury Francis Lever to introduce the bill that became the Smith–Lever Act of 1914, which established government subsidies allowing farmers voluntarily experiment with farming techniques favored by agricultural experts. Proponents of the Smith–Lever Act overcame many conservatives' objections to the act by adding provisions to bolster local control of the program, such as oversight by local colleges. By 1924, three-quarters of the agriculture-oriented counties in the United States took part in the agricultural extension program.[155] Wilson helped ensure passage of the Federal Farm Loan Act, which created twelve regional banks empowered to provide low-interest loans to farmers.[156] Another act, the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, provided federal subsidies to road-building efforts in rural areas and elsewhere.[37]

Territories and immigration

Wilson embraced the long-standing Democratic policy against owning colonies, and he worked for the gradual autonomy and ultimate independence of the Philippines, which had been acquired from Spain in the Spanish–American War. Wilson increased self-governance on the islands by granting Filipinos greater control over the Philippine Legislature. The Jones Act of 1916 committed the United States to the eventual independence of the Philippines; independence would take place in 1946.[157] The Jones Act of 1917 granted greater autonomy to Puerto Rico, which had also been acquired in the Spanish–American War. The act created the Senate of Puerto Rico, established a bill of rights, and authorized the election of a Resident Commissioner (previously appointed by the president) to a four-year term. The act also granted Puerto Ricans U.S. citizenship and exempted Puerto Rican bonds from federal, state, and local taxes.[158] In 1916, Wilson signed the Treaty of the Danish West Indies, in which the United States acquired the Danish West Indies for $25 million. After the purchase, the islands were renamed as the United States Virgin Islands.[159]

Immigration was a high priority topic in American politics during Wilson's presidency, but he gave the matter little attention.[160] Wilson's progressivism encouraged his belief that immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, though often poor and illiterate, could assimilate into a homogeneous white middle class, and he opposed the restrictive immigration policies that many members of both parties favored.[161] Wilson vetoed the Immigration Act of 1917, but Congress overrode the veto. The act's goal was to reduce immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe by requiring literacy tests, and it was the first U.S. law to restrict immigration from Europe.[162]

Judicial appointments

Wilson appointed three individuals to the United States Supreme Court while president. He appointed James Clark McReynolds in 1914; McReynolds would serve until 1941, becoming a member of the conservative bloc of the court.[163] According to Berg, Wilson viewed the appointment of the conservative McReynolds as one of the biggest mistakes he made in office.[153] In 1916, Wilson nominated Louis Brandeis to the Court, setting off a major debate in the Senate over Brandeis's progressive ideology and his religion; Brandeis was the first Jewish nominee to the Supreme Court. Ultimately, Wilson was able to convince Senate Democrats to vote for Brandeis, and Brandeis would serve until 1939.[164] Another vacancy arose in 1916, and Wilson appointed John Hessin Clarke, a progressive lawyer who served on the Court until 1922.[165]

First-term foreign policy

Latin America

Wilson sought to move away from the foreign policy of his predecessors, which he viewed as imperialistic, and he rejected Taft's Dollar Diplomacy.[166] Nonetheless, he frequently intervened in Latin American affairs, saying in 1913: "I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men."[167] The 1914 Bryan–Chamorro Treaty converted Nicaragua into a de facto protectorate, and the U.S. stationed soldiers there throughout Wilson's presidency. The Wilson administration sent troops to occupy the Dominican Republic and intervene in Haiti, and Wilson also authorized military interventions in Cuba, Panama, and Honduras.[168] The Panama Canal opened in 1914, fulfilling the long-term American goal of building a canal across Central America. The canal provided relatively swift passage between the Pacific Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean, presenting new economic opportunities to the U.S. and allowing the U.S. Navy to quickly navigate between the two oceans.

Wilson took office during the Mexican Revolution, which had begun in 1911 after liberals overthrew the military dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. Shortly before Wilson took office, conservatives retook power through a coup led by Victoriano Huerta.[169] Wilson rejected the legitimacy of Huerta's "government of butchers" and demanded Mexico hold democratic elections.[170] After Huerta arrested U.S. Navy personnel who had accidentally landed in a restricted zone near the northern port town of Tampico, Wilson dispatched the Navy to occupy the Mexican city of Veracruz. A strong backlash against the American intervention among Mexicans of all political affiliations convinced Wilson to abandon his plans to expand the U.S. military intervention, but the intervention nonetheless helped convince Huerta to flee from the country.[171] A group led by Venustiano Carranza established control over a significant proportion of Mexico, and Wilson recognized Carranza's government in October 1915.[172]

Carranza continued to face various opponents within Mexico, including Pancho Villa, whom Wilson had earlier described as "a sort of Robin Hood."[172] In early 1916, Pancho Villa raided an American town in New Mexico, killing or wounding dozens of Americans and causing an enormous nationwide American demand for his punishment. Wilson ordered General John J. Pershing and 4,000 troops across the border to capture Villa. By April, Pershing's forces had broken up and dispersed Villas bands, but Villa remained on the loose and Pershing continued his pursuit deep into Mexico. Carranza then pivoted against the Americans and accused them of a punitive invasion, leading to several incidents that nearly led to war. Tensions subsided after Mexico agreed to release several American prisoners, and bilateral negotiations began under the auspices of the Mexican-American Joint High Commission. Eager to withdraw from Mexico due to tensions in Europe, Wilson ordered Pershing to withdraw, and the last American soldiers left in February 1917.[173]

Neutrality in World War I

World War I broke out in July 1914, pitting the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria) against the Allied Powers (Britain, France, Russia, Serbia, and several other countries). The war fell into a long stalemate after the Allied Powers halted the German advance at the September 1914 First Battle of the Marne.[174] Wilson and House sought to position the United States as a mediator in the conflict, but European leaders rejected Houses's offers to help end the conflict.[175] From 1914 until early 1917, Wilson's primary foreign policy objective was to keep the United States out of the war in Europe and to broker a peace agreement.[176] He insisted that all government actions be neutral, stating that the United States "must be impartial in thought as well as in action, must put a curb upon our sentiments as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference of one party to the struggle before another."[177] The United States sought to trade with both the Allied Powers and the Central Powers, but the British imposed a blockade of Germany. After a period of negotiations, Wilson essentially assented to the British blockade; the U.S. had relatively little direct trade with the Central Powers, and Wilson was unwilling to wage war against Britain over trade issues.[178]

In response to the British blockade of the Central Powers, and over Wilson's protest, the Germans launched a submarine campaign against merchant vessels in the seas surrounding the British Isles.[179] In early 1915, the Germans sank three American ships; Wilson took the view, based on some reasonable evidence, that incidents were accidental, and that a settlement of claims could be postponed to the end of the war.[180] In May 1915, a German submarine torpedoed and sank the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania, killing 1,198, including 128 American citizens.[181] Wilson publicly responded by saying, "there is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right".[182] He also sent a protest to Germany which demanded that the German government "take immediate steps to prevent the recurrence" of incidents like the sinking of the Lusitania. In response, Bryan, who believed that Wilson had placed the defense of American trade rights above neutrality, resigned from the Cabinet.[183] In March 1916, the SS Sussex, an unarmed ferry under the French flag, was torpedoed in the English Channel and four Americans were counted among the dead. Wilson extracted from Germany a pledge to constrain submarine warfare to the rules of cruiser warfare, which represented a major diplomatic concession.[184]

During Wilson's first term, "preparedness," or building up the U.S. Army and the U.S. Navy, became a major dynamic of public opinion.[185] Interventionists, led by Theodore Roosevelt, wanted war with Germany and attacked Wilson's refusal to build up the army in anticipation of war.[186] After the sinking of the Lusitania and the resignation of Bryan, Wilson publicly committed himself to preparedness and began to build up the army and the navy.[187] In June 1916, Congress passed the National Defense Act of 1916, which established the Reserve Officers' Training Corps and expanded the National Guard.[188] Later in the year, Congress passed the Naval Act of 1916, which provided for a major expansion of the navy.[189]

Remarriage

_Margaret_Wilson%2C_Mrs._Woodrow_Wilson%2C_Jessie_Woodrow_Wilson%2C_Woodrow_Wilson%2C_Eleanor_Randolph_Wilson_(1912).png)

The health of Wilson's wife, Ellen, declined after he entered office, and doctors diagnosed her with Bright's disease in July 1914.[190] She died on August 6, 1914.[191] Wilson was deeply affected by the loss, falling into depression.[192] On March 18, 1915, Wilson met Edith Bolling Galt at a White House tea.[193] Galt was a widow and jeweler who was also from the South. After several meetings, Wilson fell in love with her, and he proposed marriage to her in May 1915. Galt initially rebuffed him, but Wilson was undeterred and continued the courtship.[194] Edith gradually warmed to the relationship, and they became engaged in September 1915.[195] They were married on December 18, 1915. Wilson joined John Tyler and Grover Cleveland as the only presidents to marry while in office.[196]

Presidential election of 1916

Wilson was renominated at the 1916 Democratic National Convention without opposition.[197] In an effort to win progressive voters, Wilson called for legislation providing for an eight-hour day and six-day workweek, health and safety measures, the prohibition of child labor, and safeguards for female workers. He also favored a minimum wage for all work performed by and for the federal government.[198] The Democrats also campaigned on the slogan, "He Kept Us Out of War," and indicated that a Republican victory would mean war with both Mexico and Germany.[199] Hoping to reunify the progressive and conservative wings of the party, the 1916 Republican National Convention nominated Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes for president. Republicans campaigned against Wilson's New Freedom policies, especially tariff reduction, the implementation of higher income taxes, and the Adamson Act, which they derided as "class legislation."[200] Though Republicans attacked Wilson's foreign policy on various grounds, domestic affairs generally dominated the campaign.[201]

By the end of election day on November 7, Wilson expected Hughes to win, but he declined to send a concession telegram until it was clear that he had lost the election.[202] The election outcome was in doubt for several days and was determined by several close states, ultimately coming down to California. On November 10, California certified that Wilson had won the state by 3,806 votes, giving him a majority of the electoral vote. In the final count, Wilson won 277 electoral votes and 49.2 percent of the popular vote, while Hughes won 254 electoral votes and 46.1 percent of the popular vote.[203] Wilson was able to win by picking up many votes that had gone to Teddy Roosevelt or Eugene V. Debs in 1912.[204] He swept the Solid South and won all but a handful of Western states, while Hughes won most of the Northeastern and Midwestern states.[205] Wilson's re-election made him the first Democrat since Andrew Jackson to win two consecutive terms. Wilson and Marshall became the first presidential ticket to win two consecutive elections since James Monroe and Daniel D. Tompkins accomplished the same feat in 1820. The Democrats also maintained control of Congress in the 1916 elections.[206]

Entering the war

In January 1917, the Germans initiated a new policy of unrestricted submarine warfare against ships in the seas around the British Isles. German leaders knew that the policy would likely provoke U.S. entrance into the war, but they hoped to defeat the Allied Powers before the U.S. could fully mobilize.[207] In late February, the U.S. public learned of the Zimmermann Telegram, a secret diplomatic communication in which Germany sought to convince Mexico to join it in a war against the United States.[208] After a series of attacks on American ships, Wilson held a Cabinet meeting on March 20; all Cabinet members agreed that the time had come for the United States to enter the war.[209] The Cabinet members believed that Germany was engaged in a commercial war against the United States, and that the United States had to respond with a formal declaration of war.[210]

On April 2, 1917, Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany, arguing that Germany was engaged in "nothing less than war against the government and people of the United States." He requested a military draft to raise the army, increased taxes to pay for military expenses, loans to Allied governments, and increased industrial and agricultural production.[211] He stated, "we have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion... no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and freedom of the nations can make them."[212] The declaration of war by the United States against Germany passed Congress with strong bipartisan majorities on April 6, 1917.[213] The United States would later declare war against Austria-Hungary in December 1917.[214]

With the U.S. entrance into the war, Wilson and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker launched an expansion of the army, with the goal of creating a 300,000-member Regular Army, a 440,000-member National Guard, and a 500,000-member conscripted force known as the "National Army." Despite some resistance to conscription and to the commitment of American soldiers abroad, large majorities of both houses of Congress voted to impose conscription with the Selective Service Act of 1917. Seeking to avoid the draft riots of the Civil War, the bill established local draft boards that were charged with determining who should be drafted. By the end of the war, nearly 3 million men had been drafted.[215] The navy also saw tremendous expansion, and Allied shipping losses dropped substantially due to U.S. contributions and a new emphasis on the convoy system.[216]

The Fourteen Points

Wilson sought the establishment of "an organized common peace" that would help prevent future conflicts. In this goal, he was opposed not just by the Central Powers, but also the other Allied Powers, who, to various degrees, sought to win concessions and oppose a punitive peace agreement on the Central Powers.[217] On January 8, 1918, Wilson delivered a speech, known as the Fourteen Points, wherein he articulated his administration's long term war objectives. Wilson called for the establishment of an association of nations to guarantee the independence and territorial integrity of all nations—a League of Nations.[218] Other points included the evacuation of occupied territory, the establishment of an independent Poland, and self-determination for the peoples of Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire.[219]

Course of the war

Under the command of General Pershing, the American Expeditionary Forces first arrived in France in mid-1917.[220] Wilson and Pershing rejected the British and French proposal that American soldiers integrate into existing Allied units, giving the United States more freedom of action but requiring for the creation of new organizations and supply chains.[221] Russia exited the war after signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, allowing Germany to shift soldiers from the Eastern Front of the war.[222] Hoping to break Allied lines before American soldiers could arrive in full force, the Germans launched the Spring Offensive on the Western Front. Both sides suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties as the Germans forced back the British and French, but Germany was unable to capture the French capital of Paris.[223] There were only 175,000 American soldiers in Europe at the end of 1917, but by mid-1918 10,000 Americans were arriving in Europe per day.[222] With American forces now in the fight, the Allies defeated Germany in the Battle of Belleau Wood and the Battle of Château-Thierry. Beginning in August, the Allies launched the Hundred Days Offensive, pushing back the exhausted German army.[224] Meanwhile, French and British leaders convinced Wilson to send a few thousand American soldiers to join the Allied intervention in Russia, which was in the midst of a civil war between the Communist Bolsheviks and the White movement.[225]

By the end of September 1918, the German leadership no longer believed it could win the war, and Kaiser Wilhelm II appointed a new government led by Prince Maximilian of Baden.[226] Baden immediately sought an armistice with Wilson, with the Fourteen Points to serve as the basis of the German surrender.[227] House procured agreement to the armistice from France and Britain, but only after threatening to conclude a unilateral armistice without them.[228] Germany and the Allied Powers brought an end to the fighting with the signing of the Armistice of 11 November 1918.[229] Austria-Hungary had signed the Armistice of Villa Giusti eight days earlier, while the Ottoman Empire had signed the Armistice of Mudros in October. By the end of the war, 116,000 American soldiers had died, and another 200,000 had been wounded.[230]

Home front

With the American entrance into World War I in April 1917, Wilson became a war-time president. The War Industries Board, headed by Bernard Baruch, was established to set U.S. war manufacturing policies and goals. Future President Herbert Hoover led the Food Administration; the Federal Fuel Administration, run by Harry Augustus Garfield, introduced daylight saving time and rationed fuel supplies; William McAdoo was in charge of war bond efforts; Vance C. McCormick headed the War Trade Board. These men, known collectively as the "war cabinet", met weekly with Wilson at the White House.[231] Because he was heavily focused on foreign policy during World War I, Wilson delegated a large degree of authority over the home front to his subordinates.[232] In the midst of the war, the federal budget soared from $1 billion in fiscal year 1916 to $19 billion in fiscal year 1919.[233] In addition to spending on its own military build-up, the United States provided large loans to the Allied countries, helping to prevent the economic collapse of Britain and France. By the end of the war, the United States had become a creditor nation for the first time in its history.[234]

Seeking to avoid the high levels of inflation that had accompanied the heavy borrowing of the American Civil War, the Wilson administration imposed further increase taxes during the war.[235] The War Revenue Act of 1917 and the Revenue Act of 1918 raised the top tax rate to 77 percent, greatly increased the number of Americans paying the income tax, and levied an excess profits tax on businesses and individuals.[236] Despite these tax acts, the United States was forced to borrow heavily to finance the war effort. Treasury Secretary McAdoo authorized the issuing of low-interest war bonds and, to attract investors, made interest on the bonds tax-free. The bonds proved so popular among investors that many borrowed money in order to buy more bonds. The purchase of bonds, along with other war-time pressures, resulted in rising inflation, though this inflation was partly matched by rising wages and profits.[233]

To shape public opinion, Wilson established the first modern propaganda office, the Committee on Public Information (CPI), headed by George Creel.[237] To suppress anti-British, pro-German, or anti-war statements, Wilson pushed through Congress the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918.[238] Because of the lack of a national police force, the Wilson administration relied heavily on state and local police forces, as well as voluntary compliance, to enforce war-time laws.[239] Anarchists, communists, Industrial Workers of the World members, and other antiwar groups attempting to sabotage the war effort were targeted by the Department of Justice; many of their leaders were arrested for incitement to violence, espionage, or sedition.[240] Eugene Debs, the 1912 Socialist presidential candidate, was among the most prominent individuals jailed for sedition. In response to concerns over civil liberties, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a private organization devoted to the defense of free speech, was founded in 1917.[241]

Aftermath of World War I

Paris Peace Conference

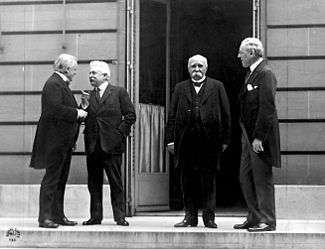

After the signing of the armistice, Wilson traveled to Europe to lead the American delegation to Paris Peace Conference, thereby becoming the first U.S. president to travel to Europe while in office.[242] Senate Republicans and even some Senate Democrats complained about their lack of representation in the American delegation, which consisted of Wilson, Colonel House,[lower-alpha 4] Secretary of State Robert Lansing, General Tasker H. Bliss, and diplomat Henry White.[244] Save for a two-week return to the United States, Wilson remained in Europe for six months, where he focused on reaching a peace treaty to formally end the war. Wilson, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando made up the "Big Four," the Allied leaders with the most influence at the Paris Peace Conference.[245]

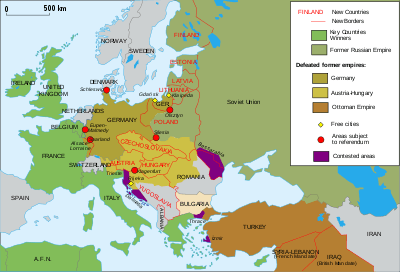

Unlike other Allied leaders, Wilson did not seek territorial gains or material concessions from the Central Powers. His chief goal was the establishment of the League of Nations, which he saw as the "keystone of the whole programme."[246] Wilson himself presided over the committee that drafted the Covenant of the League of Nations,[247] The covenant bound members to respect freedom of religion, treat racial minorities fairly, and peacefully settle disputes through organizations like the Permanent Court of International Justice. Article X of the League Covenant required all nations to defend League members against external aggression.[248] Japan proposed that the conference endorse a racial equality clause; Wilson was indifferent to the issue, but acceded to strong opposition from Australia and Britain.[249] The Covenant of the League of Nations was incorporated into the conference's Treaty of Versailles, which ended the war with Germany.[250] The covenant was also incorporated into treaties with Austria (the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye), Hungary (the Treaty of Trianon), the Ottoman Empire (the Treaty of Sèvres), and Bulgaria (the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine).[251]

Aside from the establishment of the League of Nations and the establishment of a lasting peace, Wilson's other main goal at the Paris Peace Conference was to use self-determination as the primary basis of international borders.[252] However, in pursuit of his League of Nations, Wilson conceded several points to the other powers present at the conference. Germany was required to pay war reparations and subjected to military occupation in the Rhineland. Additionally, a clause in the treaty specifically named Germany as responsible for the war. Wilson agreed to the creation of mandates in former German and Ottoman territories, allowing the European powers and Japan to establish de facto colonies in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. The Japanese acquisition of German interests in the Shandong Peninsula of China proved especially unpopular, as it undercut Wilson's promise of self-government. However, several new states were created in Central Europe and the Balkans, including Poland, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia.[253] The conference finished negotiations in May 1919, at which point German leaders viewed the treaty for the first time. Some German leaders favored repudiating the treaty, but Germany signed the treaty on June 28, 1919.[254] For his peace-making efforts, Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize.[255]

Ratification debate and incapacity

.jpg)

Ratification of the Treaty of Versailles required the support of two-thirds of the Senate, a difficult proposition given that Republicans held a narrow majority in the Senate after the 1918 elections.[256] Republicans were outraged by Wilson's failure to discuss the war or its aftermath with them, and an intensely partisan battle developed in the Senate. Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge led the opposition to the treaty; he despised Wilson and hoped to humiliate him in the ratification battle.[256] Some Republicans, including former President Taft and former Secretary of State Elihu Root, favored ratification of the treaty with some modifications, and their public support gave Wilson some chance of winning the treaty's ratification.[256]

The debate over the treaty centered around a debate over the American role in the world community in the post-war era, and senators fell into three main groups. The first group, consisting of most Democrats, favored the treaty.[256] Fourteen senators, mostly Republicans, were known as the "irreconcilables" as they completely opposed U.S. entrance into the League of Nations. Some of these irreconcilables opposed the treaty for its failure to emphasize decolonization and disarmament, while others feared surrendering American freedom of action to an international organization.[257] The remaining group of senators, known as "reservationists," accepted the idea of the league, but sought varying degrees of change to ensure the protection of U.S. sovereignty.[257] Article X of the League Covenant, which sought to create a system of collective security by requiring League members to protect one another against external aggression, was particularly unpopular among reservationists.[258] Despite the difficulty of winning ratification, Wilson consistently refused to accede to reservationists, partly due to concerns about having to re-open negotiations with the other treaty signatories.[259]

To bolster public support for ratification, Wilson barnstormed the Western states, but he returned to the White House in late September due to health problems.[260] On October 2, 1919, Wilson suffered a serious stroke, leaving him paralyzed on his left side, and with only partial vision in the right eye.[261] He was confined to bed for weeks and sequestered from everyone except his wife and his physician, Dr. Cary Grayson.[262] Dr. Bert E. Park, a neurosurgeon who examined Wilson's medical records after his death, writes that Wilson's illness affected his personality in various ways, making him prone to "disorders of emotion, impaired impulse control, and defective judgment."[263] Anxious to help the president recover, Tumulty, Grayson, and the First Lady determined what documents the president read and who was allowed to communicate with him. For her influence in the administration, some have described Edith Wilson as "the first female President of the United States."[264] In mid-November 1919, Lodge and his Republicans formed a coalition with the pro-treaty Democrats to pass a treaty with reservations, but the seriously indisposed Wilson rejected this compromise and enough Democrats followed his lead to defeat ratification.[265]

Throughout late 1919, Wilson's inner circle concealed the severity of his health issues.[266] By February 1920, the president's true condition was publicly known. Many expressed qualms about Wilson's fitness for the presidency at a time when the League fight was reaching a climax, and domestic issues such as strikes, unemployment, inflation and the threat of Communism were ablaze. No one close to Wilson was willing to certify, as required by the Constitution, his "inability to discharge the powers and duties of the said office."[267] Though some members of Congress encouraged Vice President Marshall to assert his claim to the presidency, Marshall never attempted to replace Wilson.[268] Wilson's lengthy period of incapacity while serving as president was nearly unprecedented; of the previous presidents, only James Garfield had been in a similar situation, but Garfield retained greater control of his mental faculties and faced relatively few pressing issues.[269]

Demobilization and First Red Scare

Wilson's leadership in domestic policy in the aftermath of the war was complicated by his focus on the Treaty of Versailles, opposition from the Republican-controlled Congress, and, beginning in late 1919, Wilson's illness.[270] A plan to form a commission for the purpose of demobilization of the war effort was abandoned due to the Republican control of the Senate, as Republicans could block the appointment of commission members. Instead, Wilson favored the prompt dismantling of wartime boards and regulatory agencies.[271] Demobilization was chaotic and violent; four million soldiers were sent home with little planning, little money, and few benefits. Major strikes in the steel, coal, and meatpacking industries disrupted the economy in 1919.[272] Some of the strikes turned violent, and the country experienced further turbulence as a series of race riots, primarily whites attacking blacks, broke out.[273] The country was also hit by the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed over 600,000 Americans in 1918 and 1919.[274] A massive agricultural price collapse was averted in early 1920 through the efforts of Hoover's Food Administration, but prices dropped substantially in late 1920.[275] After the expiration of wartime contracts in 1920, the U.S. plunged into a severe economic depression,[276] and unemployment rose to 11.9 percent.[277]

Following the October Revolution in the Russian Empire, many in the United States feared the possibility of a Communist-inspired revolution in the United States. These fears were inflamed by the 1919 United States anarchist bombings, which were conducted by the anarchist Luigi Galleani and his followers.[278] Fears over left-wing subversion, combined with a patriotic national mood, led to the outbreak of the so-called "First Red Scare." Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer convinced Wilson to delay amnesty for those who had been convicted of war-time sedition, and he launched the Palmer Raids to suppress radical organizations.[279] Palmer's activities met resistance from the courts and from some senior officials in the Wilson administration, but Wilson, who was physically incapacitated by late 1919, did not move to stop the raids.[280] Palmer warned of a massive 1920 May Day uprising, but after the day passed by without incident, the Red Scare largely dissipated.[281]

Prohibition and women's suffrage

Prohibition developed as an unstoppable reform during the war, but Wilson played only a minor role in its passage.[282] After decades of advocacy, in 1917 temperance groups such as the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League convinced both houses of Congress to pass a constitutional amendment imposing nationwide Prohibition. The amendment was ratified by the states in 1919, becoming the Eighteenth Amendment.[283] In October 1919, Wilson vetoed the Volstead Act, legislation designed to enforce Prohibition, but his veto was overridden by Congress.[284] Prohibition began on January 16, 1920; the manufacture, importation, sale, and transport of alcohol were prohibited, except in specific cases, such as wine used for religious purposes.[285]

Wilson personally favored women's suffrage, but early in his presidency he held that it was a state matter, partly because of strong opposition in the South to any constitutional amendment.[286] The increasingly prominent role women took in the war effort in factories and at home convinced Wilson and many others to fully support women's suffrage.[287] In a 1918 speech before Congress, Wilson for the first time endorsed a national right to vote: "We have made partners of the women in this war....Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?"[288] That same year, the House passed a constitutional amendment providing for women's suffrage nationwide, but the amendment stalled in the Senate. Wilson continually pressured the Senate to vote for the amendment, telling senators that its ratification was vital to winning the war.[289] The Senate finally approved the amendment in June 1919, and the requisite number of states ratified the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920.[290]

1920 election

Despite his ill health, Wilson continued to entertain the possibility of running for a third term. Many of Wilson's advisers tried to convince him that his health precluded another campaign, but Wilson nonetheless asked Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby to nominate him for president at the 1920 Democratic National Convention. While the convention strongly endorsed Wilson's policies, Democratic leaders were unwilling to support the ailing Wilson for a third term, and instead nominated a ticket consisting of Governor James M. Cox and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt.[291] The 1920 Republican National Convention nominated a dark horse candidate, Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio.[292] The Republicans centered their campaign around opposition to Wilson's policies, with Harding promising a "return to normalcy" to the conservative policies that had prevailed at the turn of the century. Wilson largely stayed out of the campaign, although he endorsed Cox and continued to advocate for U.S. membership in the League of Nations. Harding won a landslide victory, taking 60.3 percent of the popular vote and winning every state outside of the South.[293] Wilson met with Harding for tea on his last day in office, March 3, 1921, but health issues prevented him from taking part in Harding's inauguration ceremonies.[294]

Final years and death

After the end of his second term in 1921, Wilson and his wife moved from the White House to a town house in the Kalorama section of Washington, D.C.[295] He continued to follow politics as President Harding and the Republican Congress repudiated membership in the League of Nations, cut taxes, and raised tariffs.[296] In 1921, Wilson opened a law office with former Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby, but Wilson's second attempt at practicing law proved no more enjoyable than his first, and the practice was closed by the end of 1922. Wilson experienced more success with his return to writing, and he published short works on the international impact of the American Revolution and the rise of totalitarianism.[297] He declined to write memoirs, but frequently met with Ray Stannard Baker, who wrote a three-volume biography of Wilson that was published in 1922.[298] In August 1923, Wilson attended the funeral of his successor, Warren Harding.[297] On November 10, 1923, Wilson made his last national address, delivering a short Armistice Day radio speech from the library of his home.[299][300]

Wilson's health did not markedly improve after leaving office; his left arm and left leg were both paralyzed, and he frequently suffered digestive tract issues.[301] His health declined throughout January 1924, and he died on February 3, 1924.[302] He was interred in a sarcophagus in Washington National Cathedral and is the only president interred in the nation's capital.[303]

Race relations

Wilson was the first Southerner to be elected president since Zachary Taylor was elected in 1848, and his ascension to the presidency was celebrated by southern segregationists. The federal government had pursued racist policies for decades, not limited to early defenses of slavery, treatment of Native Americans, intervention policies in Latin America, and immigration policies that specifically prevented Africans and Asians from immigrating to the United States. Several historians have spotlighted consistent examples in the public record of Wilson's overtly racist policies and political appointments, such as segregationists he placed in his Cabinet.[304][305][306][307][308] Ross Kennedy writes that Wilson's support of segregation complied with predominant public opinion,[309] and A. Scott Berg argues that Wilson accepted segregation as part of a policy to "promote racial progress... by shocking the social system as little as possible."[310] Historian Kendrick Clements argues that "Wilson had none of the crude, vicious racism of James K. Vardaman or Benjamin R. Tillman, but he was insensitive to African-American feelings and aspirations."[311]

Wilson continued to appoint African Americans to positions that had traditionally been filled by blacks, overcoming opposition from many southern senators.[312] However, the Wilson administration escalated the discriminatory hiring policies and segregation of government offices that had begun under President Theodore Roosevelt, and had continued under President Taft.[313] In Wilson's first month in office, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson urged the president to establish segregated government offices.[314] Wilson did not adopt Burleson's proposal to segregate all government departments, but he allowed Cabinet members to segregate their respective departments.[315] By the end of 1913, many departments, including the navy, had segregated work spaces, restrooms, and cafeterias.[314] There was almost no opposition in Congress toward these policies, most of which would stay in place for years afterward. Wilson's African-American supporters, who had crossed party lines to vote for him in 1912, were bitterly disappointed, and they protested these changes.[314] Wilson defended his administration's segregation policy in a July 1913 letter responding to civil rights activist Oswald Garrison Villard, arguing that segregation removed "friction" between the races.[314]