International Labour Organization

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice through setting international labour standards.[1] Founded in 1919 under the League of Nations, it is the first and oldest specialised agency of the UN. The ILO has 187 member states: 186 out of 193 UN member states plus the Cook Islands. It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, with around 40 field offices around the world, and employs some 2,700 staff from over 150 nations, of whom 900 work in technical cooperation programmes and projects.

| |

| |

| Abbreviation | ILO |

|---|---|

| Formation | 29 October 1919 |

| Type | United Nations specialized agency |

| Legal status | Active |

| Headquarters | Geneva, Switzerland |

Head | Director-General |

Parent organization | United Nations General Assembly United Nations Economic and Social Council |

| Website | www.ilo.org |

The ILO's international labour standards are broadly aimed at ensuring accessible, productive, and sustainable work worldwide in conditions of freedom, equity, security and dignity.[2][3] They are set forth in 189 conventions and treaties, of which eight are classified as fundamental according to the 1998 Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work; together they protect freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of forced or compulsory labour, the abolition of child labour, and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation. The ILO is subsequently a major contributor to international labour law.

Within the UN system the organization has a unique tripartite structure: all standards, policies, and programmes require discussion and approval from the representatives of governments, employers, and workers. This framework is maintained in the ILO's three main bodies: The International Labour Conference, which meets annually to formulate international labour standards; the Governing Body, which serves as the executive council and decides the agency's policy and budget; and the International Labour Office, the permanent secretariat that administers the organization and implements activities. The secretariat is led by the Director-General, currently Guy Ryder of the United Kingdom, who was elected by the Governing Body in 2012.

In 1969, the ILO received the Nobel Peace Prize for improving fraternity and peace among nations, pursuing decent work and justice for workers, and providing technical assistance to other developing nations.[4] In 2019, the organization convened the Global Commission on the Future of Work, whose report made ten recommendations for governments to meet the challenges of the 21st century labor environment; these include a universal labour guarantee, social protection from birth to old age and an entitlement to lifelong learning.[5][6] With its focus on international development, it is a member of the United Nations Development Group, a coalition of UN organization aimed at helping meet the Sustainable Development Goals.

Governance, organization, and membership

Unlike other United Nations specialized agencies, the International Labour Organization has a tripartite governing structure that brings together governments, employers, and workers of 187 member States, to set labour standards, develop policies and devise programmes promoting decent work for all women and men. The structure is intended to ensure the views of all three groups are reflected in ILO labour standards, policies, and programmes, though governments have twice as many representatives as the other two groups.

Governing body

The Governing Body is the executive body of the International Labour Organization. It meets three times a year, in March, June and November. It takes decisions on ILO policy, decides the agenda of the International Labour Conference, adopts the draft Programme and Budget of the Organization for submission to the Conference, elects the Director-General, requests information from the member states concerning labour matters, appoints commissions of inquiry and supervises the work of the International Labour Office.

Juan Somavía was the ILO's Director-General from 1999 until October 2012 when Guy Ryder was elected. The ILO Governing Body re-elected Guy Rider as Director-General for a second five-year-term in November 2016.[7]

This governing body is composed of 56 titular members (28 governments, 14 employers and 14 workers) and 66 deputy members (28 governments, 19 employers and 19 workers).

Ten of the titular government seats are permanently held by States of chief industrial importance: Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom and the United States.[8] The other Government members are elected by the Conference every three years (the last elections were held in June 2017). The Employer and Worker members are elected in their individual capacity.[9][10]

International Labour Conference

The ILO organises once a year the International Labour Conference in Geneva to set the broad policies of the ILO, including conventions and recommendations.[11] Also known as the "international parliament of labour", the conference makes decisions about the ILO's general policy, work programme and budget and also elects the Governing Body.

Each member state is represented by a delegation: two government delegates, an employer delegate, a worker delegate and their respective advisers. All of them have individual voting rights and all votes are equal, regardless the population of the delegate's member State. The employer and worker delegates are normally chosen in agreement with the most representative national organizations of employers and workers. Usually, the workers and employers' delegates coordinate their voting. All delegates have the same rights and are not required to vote in blocs.

Delegate have the same rights, they can express themselves freely and vote as they wish. This diversity of viewpoints does not prevent decisions being adopted by very large majorities or unanimously.

Heads of State and prime ministers also participate in the Conference. International organizations, both governmental and others, also attend but as observers.

Membership

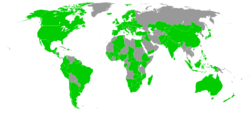

The ILO has 187 state members. 186 of the 193 member states of the United Nations plus the Cook Islands are members of the ILO.[12] The UN member states which are not members of the ILO are Andorra, Bhutan, Liechtenstein, Micronesia, Monaco, Nauru, and North Korea.

The ILO constitution permits any member of the UN to become a member of the ILO. To gain membership, a nation must inform the director-general that it accepts all the obligations of the ILO constitution.[13] Other states can be admitted by a two-thirds vote of all delegates, including a two-thirds vote of government delegates, at any ILO General Conference. The Cook Islands, a non-UN state, joined in June 2015.

Members of the ILO under the League of Nations automatically became members when the organization's new constitution came into effect after World War II.

Position within the UN

The ILO is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN).[14] As with other UN specialized agencies (or programmes) working on international development, the ILO is also a member of the United Nations Development Group.[15]

Normative function

Conventions

Through July 2018, the ILO had adopted 189 conventions. If these conventions are ratified by enough governments, they come in force. However, ILO conventions are considered international labour standards regardless of ratification. When a convention comes into force, it creates a legal obligation for ratifying nations to apply its provisions.

Every year the International Labour Conference's Committee on the Application of Standards examines a number of alleged breaches of international labour standards. Governments are required to submit reports detailing their compliance with the obligations of the conventions they have ratified. Conventions that have not been ratified by member states have the same legal force as recommendations.

In 1998, the 86th International Labour Conference adopted the Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. This declaration contains four fundamental policies:[16]

- The right of workers to associate freely and bargain collectively

- The end of forced and compulsory labour

- The end of child labour

- The end of unfair discrimination among workers

The ILO asserts that its members have an obligation to work towards fully respecting these principles, embodied in relevant ILO conventions. The ILO conventions which embody the fundamental principles have now been ratified by most member states.[17]

Protocols

This device is employed for making conventions more flexible or for amplifying obligations by amending or adding provisions on different points. Protocols are always linked to Convention, even though they are international treaties they do not exist on their own. As with Conventions, Protocols can be ratified.

Recommendations

Recommendations do not have the binding force of conventions and are not subject to ratification. Recommendations may be adopted at the same time as conventions to supplement the latter with additional or more detailed provisions. In other cases recommendations may be adopted separately and may address issues separate from particular conventions.[18]

History

Origins

While the ILO was established as an agency of the League of Nations following World War I, its founders had made great strides in social thought and action before 1919. The core members all knew one another from earlier private professional and ideological networks, in which they exchanged knowledge, experiences, and ideas on social policy. Prewar "epistemic communities", such as the International Association for Labour Legislation (IALL), founded in 1900, and political networks, such as the socialist Second International, were a decisive factor in the institutionalization of international labour politics.[19]

In the post–World War I euphoria, the idea of a "makeable society" was an important catalyst behind the social engineering of the ILO architects. As a new discipline, international labour law became a useful instrument for putting social reforms into practice. The utopian ideals of the founding members—social justice and the right to decent work—were changed by diplomatic and political compromises made at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, showing the ILO's balance between idealism and pragmatism.[19]

Over the course of the First World War, the international labour movement proposed a comprehensive programme of protection for the working classes, conceived as compensation for labour's support during the war. Post-war reconstruction and the protection of labour unions occupied the attention of many nations during and immediately after World War I. In Great Britain, the Whitley Commission, a subcommittee of the Reconstruction Commission, recommended in its July 1918 Final Report that "industrial councils" be established throughout the world.[20] The British Labour Party had issued its own reconstruction programme in the document titled Labour and the New Social Order.[21] In February 1918, the third Inter-Allied Labour and Socialist Conference (representing delegates from Great Britain, France, Belgium and Italy) issued its report, advocating an international labour rights body, an end to secret diplomacy, and other goals.[22] And in December 1918, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) issued its own distinctively apolitical report, which called for the achievement of numerous incremental improvements via the collective bargaining process.[23]

IFTU Bern Conference

As the war drew to a close, two competing visions for the post-war world emerged. The first was offered by the International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU), which called for a meeting in Bern, Switzerland, in July 1919. The Bern meeting would consider both the future of the IFTU and the various proposals which had been made in the previous few years. The IFTU also proposed including delegates from the Central Powers as equals. Samuel Gompers, president of the AFL, boycotted the meeting, wanting the Central Powers delegates in a subservient role as an admission of guilt for their countries' role in the bringing about war. Instead, Gompers favoured a meeting in Paris which would only consider President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points as a platform. Despite the American boycott, the Bern meeting went ahead as scheduled. In its final report, the Bern Conference demanded an end to wage labour and the establishment of socialism. If these ends could not be immediately achieved, then an international body attached to the League of Nations should enact and enforce legislation to protect workers and trade unions.[23]

Commission on International Labour Legislation

Meanwhile, the Paris Peace Conference sought to dampen public support for communism. Subsequently, the Allied Powers agreed that clauses should be inserted into the emerging peace treaty protecting labour unions and workers' rights, and that an international labour body be established to help guide international labour relations in the future. The advisory Commission on International Labour Legislation was established by the Peace Conference to draft these proposals. The Commission met for the first time on 1 February 1919, and Gompers was elected as the chairman.[23]

Two competing proposals for an international body emerged during the Commission's meetings. The British proposed establishing an international parliament to enact labour laws which each member of the League would be required to implement. Each nation would have two delegates to the parliament, one each from labour and management.[23] An international labour office would collect statistics on labour issues and enforce the new international laws. Philosophically opposed to the concept of an international parliament and convinced that international standards would lower the few protections achieved in the United States, Gompers proposed that the international labour body be authorized only to make recommendations, and that enforcement be left up to the League of Nations. Despite vigorous opposition from the British, the American proposal was adopted.[23]

Gompers also set the agenda for the draft charter protecting workers' rights. The Americans made 10 proposals. Three were adopted without change: That labour should not be treated as a commodity; that all workers had the right to a wage sufficient to live on; and that women should receive equal pay for equal work. A proposal protecting the freedom of speech, press, assembly, and association was amended to include only freedom of association. A proposed ban on the international shipment of goods made by children under the age of 16 was amended to ban goods made by children under the age of 14. A proposal to require an eight-hour work day was amended to require the eight-hour work day or the 40-hour work week (an exception was made for countries where productivity was low). Four other American proposals were rejected. Meanwhile, international delegates proposed three additional clauses, which were adopted: One or more days for weekly rest; equality of laws for foreign workers; and regular and frequent inspection of factory conditions.[23]

The Commission issued its final report on 4 March 1919, and the Peace Conference adopted it without amendment on 11 April. The report became Part XIII of the Treaty of Versailles.[23]

Interwar period

The first annual conference, referred to as the International Labour Conference (ILC), began on 29 October 1919 at the Pan American Union Building in Washington, D.C.[24] and adopted the first six International Labour Conventions, which dealt with hours of work in industry, unemployment, maternity protection, night work for women, minimum age, and night work for young persons in industry.[25] The prominent French socialist Albert Thomas became its first director-general.

Despite open disappointment and sharp critique, the revived International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU) quickly adapted itself to this mechanism. The IFTU increasingly oriented its international activities around the lobby work of the ILO.[26]

At the time of establishment, the U.S. government was not a member of ILO, as the US Senate rejected the covenant of the League of Nations, and the United States could not join any of its agencies. Following the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the U.S. presidency, the new administration made renewed efforts to join the ILO without league membership. On 19 June 1934, the U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution authorizing the president to join ILO without joining the League of Nations as a whole. On 22 June 1934, the ILO adopted a resolution inviting the U.S. government to join the organization. On 20 August 1934, the U.S. government responded positively and took its seat at the ILO.

Wartime and the United Nations

During the Second World War, when Switzerland was surrounded by German troops, ILO director John G. Winant made the decision to leave Geneva. In August 1940, the government of Canada officially invited the ILO to be housed at McGill University in Montreal. Forty staff members were transferred to the temporary offices and continued to work from McGill until 1948.[27]

The ILO became the first specialized agency of the United Nations system after the demise of the league in 1946.[28] Its constitution, as amended, includes the Declaration of Philadelphia (1944) on the aims and purposes of the organization.

Cold War era

Beginning in the late 1950s the organization was under pressure to make provisions for the potential membership of ex-colonies which had become independent; in the Director General’s report of 1963 the needs of the potential new members were first recognized.[29] The tensions produced by these changes in the world environment negatively affected the established politics within the organization[30] and they were the precursor to the eventual problems of the organization with the USA

In July, 1970, the United States withdrew 50% of its financial support to the ILO following the appointment of an assistant director-general from the Soviet Union. This appointment (by the ILO's British director-general, C. Wilfred Jenks) drew particular criticism from AFL–CIO president George Meany and from Congressman John E. Rooney. However, the funds were eventually paid.[31][32]

On 12 June 1975, the ILO voted to grant the Palestinian Liberation Organization observer status at its meetings. Representatives of the United States and Israel walked out of the meeting. The U.S. House of Representatives subsequently decided to withhold funds. The United States gave notice of full withdrawal on 6 November 1975, stating that the organization had become politicized. The United States also suggested that representation from communist countries was not truly "tripartite"—including government, workers, and employers—because of the structure of these economies. The withdrawal became effective on 1 November 1977.[31]

The United States returned to the organization in 1980 after extracting some concession from the organization. It was partly responsible for the ILO's shift away from a human rights approach and towards support for the Washington Consensus. Economist Guy Standing wrote "the ILO quietly ceased to be an international body attempting to redress structural inequality and became one promoting employment equity".[33]

In 1981, the government of Poland declared martial law. It interrupted the activities of Solidarnosc detained many of its leaders and members. The ILO Committee on Freedom of Association filed a complaint against Poland at the 1982 International Labour Conference. A Commission of Inquiry established to investigate found Poland had violated ILO Conventions No. 87 on freedom of association[34] and No. 98 on trade union rights,[35] which the country had ratified in 1957. The ILO and many other countries and organizations put pressure on the Polish government, which finally gave legal status to Solidarnosc in 1989. During that same year, there was a roundtable discussion between the government and Solidarnoc which agreed on terms of relegalization of the organization under ILO principles. The government also agreed to hold the first free elections in Poland since the Second World War.[36]

Programmes

Labour statistics

The ILO is a major provider of labour statistics. Labour statistics are an important tool for its member states to monitor their progress toward improving labour standards. As part of their statistical work, ILO maintains several databases.[37] This database covers 11 major data series for over 200 countries. In addition, ILO publishes a number of compilations of labour statistics, such as the Key Indicators of Labour Markets[38] (KILM). KILM covers 20 main indicators on labour participation rates, employment, unemployment, educational attainment, labour cost, and economic performance. Many of these indicators have been prepared by other organizations. For example, the Division of International Labour Comparisons of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics prepares the hourly compensation in manufacturing indicator.[39]

The U.S. Department of Labor also publishes a yearly report containing a List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor[40] issued by the Bureau of International Labor Affairs. The December 2014 updated edition of the report listed a total of 74 countries and 136 goods.

Training and teaching units

The International Training Centre of the International Labour Organization (ITCILO) is based in Turin, Italy.[41] Together with the University of Turin Department of Law, the ITC offers training for ILO officers and secretariat members, as well as offering educational programmes. The ITC offers more than 450 training and educational programmes and projects every year for some 11,000 people around the world.

For instance, the ITCILO offers a Master of Laws programme in management of development, which aims specialize professionals in the field of cooperation and development.[42]

Child labour

The term child labour is often defined as work that deprives children of their childhood, potential, dignity, and is harmful to their physical and mental development.

Child labour refers to work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children. Further, it can involve interfering with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school, obliging them to leave school prematurely, or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work.

In its most extreme forms, child labour involves children being enslaved, separated from their families, exposed to serious hazards and illnesses and left to fend for themselves on the streets of large cities – often at a very early age. Whether or not particular forms of "work" can be called child labour depends on the child's age, the type and hours of work performed, the conditions under which it is performed and the objectives pursued by individual countries. The answer varies from country to country, as well as among sectors within countries.

ILO's response to child labour

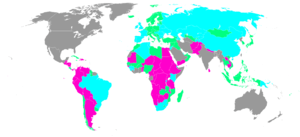

The ILO's International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) was created in 1992 with the overall goal of the progressive elimination of child labour, which was to be achieved through strengthening the capacity of countries to deal with the problem and promoting a worldwide movement to combat child labour. The IPEC currently has operations in 88 countries, with an annual expenditure on technical cooperation projects that reached over US$61 million in 2008. It is the largest programme of its kind globally and the biggest single operational programme of the ILO.

The number and range of the IPEC's partners have expanded over the years and now include employers' and workers' organizations, other international and government agencies, private businesses, community-based organizations, NGOs, the media, parliamentarians, the judiciary, universities, religious groups and children and their families.

The IPEC's work to eliminate child labour is an important facet of the ILO's Decent Work Agenda.[43] Child labour not only prevents children from acquiring the skills and education they need for a better future,[44]

Exceptions in indigenous communities

Because of different cultural views involving labour, the ILO developed a series of culturally sensitive mandates, including convention Nos. 169, 107, 138, and 182, to protect indigenous culture, traditions, and identities. Convention Nos. 138 and 182 lead in the fight against child labour, while Nos. 107 and 169 promote the rights of indigenous and tribal peoples and protect their right to define their own developmental priorities.[45]

In many indigenous communities, parents believe children learn important life lessons through the act of work and through the participation in daily life. Working is seen as a learning process preparing children of the future tasks they will eventually have to do as an adult.[46] It is a belief that the family's and child well-being and survival is a shared responsibility between members of the whole family. They also see work as an intrinsic part of their child's developmental process. While these attitudes toward child work remain, many children and parents from indigenous communities still highly value education.[45]

Issues

Forced labour

The ILO has considered the fight against forced labour to be one of its main priorities. During the interwar years, the issue was mainly considered a colonial phenomenon, and the ILO's concern was to establish minimum standards protecting the inhabitants of colonies from the worst abuses committed by economic interests. After 1945, the goal became to set a uniform and universal standard, determined by the higher awareness gained during World War II of politically and economically motivated systems of forced labour, but debates were hampered by the Cold War and by exemptions claimed by colonial powers. Since the 1960s, declarations of labour standards as a component of human rights have been weakened by government of postcolonial countries claiming a need to exercise extraordinary powers over labour in their role as emergency regimes promoting rapid economic development.[47]

In June 1998 the International Labour Conference adopted a Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its follow-up that obligates member states to respect, promote and realize freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour, the effective abolition of child labour, and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

With the adoption of the declaration, the ILO created the InFocus Programme on Promoting the Declaration which is responsible for the reporting processes and technical cooperation activities associated with the declaration; and it carries out awareness raising, advocacy and knowledge functions.

In November 2001, following the publication of the InFocus Programme's first global report on forced labour, the ILO's governing body created a special action programme to combat forced labour (SAP-FL),[48] as part of broader efforts to promote the 1998 Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its follow-up.

Since its inception, the SAP-FL has focused on raising global awareness of forced labour in its different forms, and mobilizing action against its manifestation. Several thematic and country-specific studies and surveys have since been undertaken, on such diverse aspects of forced labour as bonded labour, human trafficking, forced domestic work, rural servitude, and forced prisoner labour.

In 2013, the SAP-FL was integrated into the ILO's Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work Branch (FUNDAMENTALS)[49] bringing together the fight against forced and child labour and working in the context of Alliance 8.7.[50]

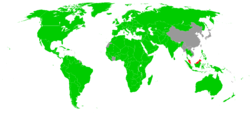

One major tool to fight forced labour was the adoption of the ILO Forced Labour Protocol by the International Labour Conference in 2014. It was ratified for the second time in 2015 and in 9 November 2016 it entered into force. The new protocol brings the existing ILO Convention 29 on Forced Labour,[51] adopted in 1930, into the modern era to address practices such as human trafficking. The accompanying Recommendation 203 provides technical guidance on its implementation.[52]

In 2015, the ILO launched a global campaign to end modern slavery, in partnership with the International Organization of Employers (IOE) and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). The 50 for Freedom campaign aims to mobilize public support and encourage countries to ratify the ILO’s Forced Labour Protocol.[53]

Minimum wage law

To protect the right of labours for fixing minimum wage, ILO has created Minimum Wage-Fixing Machinery Convention, 1928, Minimum Wage Fixing Machinery (Agriculture) Convention, 1951 and Minimum Wage Fixing Convention, 1970 as minimum wage law.

HIV/AIDS

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is the lead UN-agency on HIV workplace policies and programmes and private sector mobilization. ILOAIDS[54] is the branch of the ILO dedicated to this issue.

The ILO has been involved with the HIV response since 1998, attempting to prevent potentially devastating impact on labour and productivity and that it says can be an enormous burden for working people, their families and communities. In June 2001, the ILO's governing body adopted a pioneering code of practice on HIV/AIDS and the world of work,[55] which was launched during a special session of the UN General Assembly.

The same year, ILO became a cosponsor of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

In 2010, the 99th International Labour Conference adopted the ILO's recommendation concerning HIV and AIDS and the world of work, 2010 (No. 200),[56] the first international labour standard on HIV and AIDS. The recommendation lays out a comprehensive set of principles to protect the rights of HIV-positive workers and their families, while scaling up prevention in the workplace. Working under the theme of Preventing HIV, Protecting Human Rights at Work, ILOAIDS undertakes a range of policy advisory, research and technical support functions in the area of HIV and AIDS and the world of work. The ILO also works on promoting social protection as a means of reducing vulnerability to HIV and mitigating its impact on those living with or affected by HIV.

ILOAIDS ran a "Getting to Zero"[57] campaign to arrive at zero new infections, zero AIDS-related deaths and zero-discrimination by 2015.[58] Building on this campaign, ILOAIDS is executing a programme of voluntary and confidential counselling and testing at work, known as VCT@WORK.[59]

Migrant workers

As the word "migrant" suggests, migrant workers refer to those who moves from one country to another to do their job. For the rights of migrant workers, ILO has adopted conventions, including Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention, 1975 and United Nations Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families in 1990.[60]

Domestic workers

Domestic workers are those who perform a variety of tasks for and in other peoples' homes. For example, they may cook, clean the house, and look after children. Yet they are often the ones with the least consideration, excluded from labour and social protection. This is mainly due to the fact that women have traditionally carried out the tasks without pay.[61] For the rights and decent work of domestic workers including migrant domestic workers, ILO has adopted the Convention on Domestic Workers on 16 June 2011.

ILO and globalization

Seeking a process of globalization that is inclusive, democratically governed and provides opportunities and tangible benefits for all countries and people. The World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalization was established by the ILO's governing body in February 2002 at the initiative of the director-general in response to the fact that there did not appear to be a space within the multilateral system that would cover adequately and comprehensively the social dimension of the various aspects of globalization. The World Commission Report, A Fair Globalization: Creating Opportunities for All, is the first attempt at structured dialogue among representatives of constituencies with different interests and opinions on the social dimension of globalization.[62]

Future of Work

The ILO launched the Future of Work Initiative in order to gain understanding on the transformations that occur in the world of work and thus be able to develop ways of responding to these challenges.[63] The initiative begun in 2016 by gathering the views of government representatives, workers, employers, academics and other relevant figures around the world. About 110 countries participated in dialogues at the regional and national level. These dialogues were structured around "four centenary conversations: work and society, decent jobs for all, the organization of work and production, and the governance of work." The second step took place in 2017 with the establishment of the Global Commission on the Future of Work dealing with the same "four centenary conversations". A report is expected to be published prior to the 2019 Centenary International Labour Conference. ILO is also assessing the impact of technological disruptions on employments worldwide. The agency is worried about the global economic and health impact of technology, like industrial and process automation, artificial intelligence (AI), Robots and robotic process of automation on human labor and is increasingly being considered by commentators, but in widely divergent ways. Among the salient views technology will bring less work, make workers redundant or end work by replacing the human labor. The other fold of view is technological creativity and abundant opportunities for economy boosts. In the modern era, technology has changed the way we think, design, and deploy the system solutions but no doubt there are threats to human jobs. Paul Schulte (Director of the Education and Information Division, and Co-Manager of the Nanotechnology Research Center, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control) and DP Sharma, (International Consultant, Information Technology and Scientist) clearly articulated such disruptions and warned that it will be worse than ever before if appropriate actions will not be taken timely.He said that human generation needs to reinvent in terms of competitive accuracy, speed, capacity and honesty. Machines are more honest than human labours and its a crystal clear threat to this generation. The science and technology have no reverse gear and accepting the challenge " Human vs. Machine" is the only remedy for survival.[64][65][66][67]

The ILO has also looked at the transition to a green economy, and the impact thereof on employment. It came to the conclusion a shift to a greener economy could create 24 million new jobs globally by 2030, if the right policies are put in place. Also, if a transition to a green economy were not to take place, 72 million full-time jobs may be lost by 2030 due to heat stress, and temperature increases will lead to shorter available work hours, particularly in agriculture[68][69]

See also

- Administrative Tribunal of the International Labour Organization

- Centre William Rappard, first permanent home of the ILO on the north bank of Lake Geneva

- League of Nations archives

- Seoul Declaration on Safety and Health at Work, 2008

- Social clause, the integration of seven core ILO labour rights conventions into trade agreements

- Total Digital Access to the League of Nations Archives Project (LONTAD)

- United Nations Global Compact, 1999–2000, encouraging businesses to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies

References

- "Mission and impact of the ILO". ilo.org.

- St, International Labour; Switzerl, ards DepartmentRoute des Morillons 4 CH-1211 Geneva 22. "Labour standards". www.ilo.org. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Introduction to International Labour Standards". ilo.org.

- "The Nobel Peace Prize 1969". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 5 July 2006.

- "Global Commission on the Future of Work". www.ilo.org. 14 August 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "A human-centred agenda needed for a decent future of work". www.ilo.org. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "Guy Ryder re-elected as ILO Director-General for a second term". ilo.org.

- "Governing Body". ilo.org. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Article 7, ILO Constitution

- "ILO Constitution". ilo.org.

- "International Labour Conference". ilo.org. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "ILO Constitution Article 3". Ilo.org. Archived from the original on 25 December 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- "The International Labour Organization (ILO) – Membership". Encyclopedia of the Nations. Advameg, Inc. 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- "International Labour Organization". britannica.com. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work". Rights at Work. International Labour Organization. 1998. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- See the list of ratifications at Ilo.org

- "Recommendations". www.ilo.org.

- VanDaele, Jasmien (2005). "Engineering Social Peace: Networks, Ideas, And the Founding of the International Labour Organization". International Review of Social History. 50 (3): 435–466. doi:10.1017/S0020859005002178.

- Haimson, Leopold H. and Sapelli, Giulio. Strikes, Social Conflict, and the First World War: An International Perspective. Milan: Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, 1992. ISBN 88-07-99047-4

- Shapiro, Stanley (1976). "The Passage of Power: Labor and the New Social Order". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 120 (6): 464–474. JSTOR 986599.

- Ayusawa, Iwao Frederick. International Labour Legislation. Clark, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 2005. ISBN 1-58477-461-4

- Foner, Philip S. History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. 7: Labor and World War I, 1914–1918. New York: International Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-7178-0638-3

- "INTERNATIONAL LABOR CONFERENCE. October 29, 1919 – NOVEMBER 29, 1919" (PDF). ilo.org. WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1920.

- "Origins and history". ilo.org.

- Reiner Tosstorff (2005). "The International Trade-Union Movement and the Founding of the International Labour Organization" (PDF). International Review of Social History. 50 (3): 399–433. doi:10.1017/S0020859005002166.

- "ILO". ilo.org.

- "Photo Gallery". ILO. 2011. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ILO: 'Programme and Structure of the ILO':report of the Director General, 1963.

- R. W. Cox, "ILO: Limited Monarchy" in R.W. Cox and H. Jacobson The Anatomy of Influence: Decision Making in International Organization Yale University Press, 1973 pp.102-138

- Beigbeder, Yves (1979). "The United States' Withdrawal from the International Labor Organization" (PDF). Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations. 34 (2): 223–240. doi:10.7202/028959ar.

- "Communication from the Government of the United States" (PDF). ilo.org.. United States letter dated 5 November 1975 containing notice of withdrawal from the International Labour Organization.

- Standing, Guy (2008). "The ILO: An Agency for Globalization?" (PDF). Development and Change. 39 (3): 355–384. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.593.4931. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00484.x. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- "ILO Conventions No. 98". ilo.org.

- "ILO Conventions No. 98". ilo.org.

- "The ILO and the story of Solidarnoc". ilo.org.

- "ILO statistics overview". ilo.org.

- "Key Indicators of the Labour Market (KILM)". ilo.org.

- "Hourly compensation costs" (PDF). International Labour Organization, KILM 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- "List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor". dol.gov.

- BIZZOTTO. "ITCILO – International Training Center". Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "LLM Guide (IP LLM) – University of Torino, Faculty of Law". llm-guide.com. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Von Braun, Joachim (1995). Von Braun (ed.). Employment for poverty reduction and food security. IFPRI Occasional Papers. Intl Food Policy Res Inst. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-89629-332-8. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- Larsen, P.B. Indigenous and tribal children: assessing child labour and education challenges. International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC), International Labour Office.

- Guidelines for Combating Child Labour Among Indigenous Peoples. Geneva: International Labour Organization. 2006. ISBN 978-92-2-118748-6.

- Daniel Roger Maul (2007). "The International Labour Organization and the Struggle against Forced Labour from 1919 to the Present". Labor History. 48 (4): 477–500. doi:10.1080/00236560701580275.

- "Forced labour, human trafficking and slavery". ilo.org.

- "FUNDAMENTALS". ilo.org.

- "Alliance 8.7". alliance87.org.

- "ILO Convention 29".

- "ILO Recommendation 203".

- "50 for freedom".

- "HIV/AIDS and the World of Work Branch (ILOAIDS)". ilo.org.

- "The ILO Code of Practice on HIV/AIDS and the World of Work". ilo.org.

- "Recommendation concerning HIV and AIDS and the World of Work, 2010 (No. 200)". ilo.org.

- "Getting to Zero". Archived from the original on 9 December 2014.

- "UNAIDS". unaids.org.

- "VCT@WORK: 5 million women and men workers reached with Voluntary and confidential HIV Counseling and Testing by 2015". ilo.org.

- Kumaraveloo, K Sakthiaseelan; Lunner Kolstrup, Christina (3 July 2018). "Agriculture and musculoskeletal disorders in low- and middle-income countries". Journal of Agromedicine. 23 (3): 227–248. doi:10.1080/1059924x.2018.1458671. ISSN 1059-924X. PMID 30047854.

- "Domestic workers". ilo.org. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "The Future of Work".

- "The Future of Work".

- Howard, Paul Schulte & John (9 March 2019). "The impact of technology on work and the workforce". www.ilo.org. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "इंडस्ट्रियल इंटरनेट ऑफ़ थिंग्स से 5 साल में 20-34 प्रतिशत रोजगार हो जाएंगे कम : प्रोफेसर शर्मा". Patrika News (in Hindi). Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- "An Entrepreneur Should Be Aware of the Dangers in Human Resource Tech". www.internationalnewsandviews.com. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- "Industrial development should be balanced with natural justice and development". www.internationalnewsandviews.com. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Green economy could create 24 million new jobs

- Greening with jobs – World Employment and Social Outlook 2018

Further reading

- Alcock, A. History of the International Labour Organization (London, 1971)

- Chisholm, A. Labour's Magna Charta: A Critical Study of the Labour Clauses of the Peace Treaty and of the Draft Conventions and Recommendations of the Washington International Labour Conference (London, 1925)

- Dufty, N.F. "Organizational Growth and Goal Structure: The Case of the ILO," International Organization 1972 Vol. 26, pp 479–498 in JSTOR

- Endres, A.; Fleming, G. International Organizations and the Analysis of Economic Policy, 1919–1950 (Cambridge, 2002)

- Evans, A.A. My Life as an International Civil Servant in the International Labour Organization (Geneva, 1995)

- Ewing, K. Britain and the ILO (London, 1994)

- Fried, John H. E. "Relations Between the United Nations and the International Labor Organization," American Political Science Review, Vol. 41, No. 5 (October 1947), pp. 963–977 in JSTOR

- Galenson, Walter. The International Labor Organization: An American View (Madison, 1981)

- Ghebali, Victor-Yves. "The International Labour Organisation : A Case Study on the Evolution of U.N. Specialised Agencies" Dordrecht, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, (1989)

- Guthrie, Jason. "The international labor organization and the social politics of development, 1938–1969." (PhD Dissertation, University of Maryland, 2015).

- Haas, Ernst B. "Beyond the nation-state: functionalism and international organization" Colchester, ECPR Press, (2008)

- Heldal, H. "Norway in the International Labour Organization, 1919–1939" Scandinavian Journal of History 1996 Vol. 21, pp 255–283,

- Imber, M.F. The USA, ILO, UNESCO and IAEA: politicization and withdrawal in the Specialized Agencies (1989)

- Johnston, G.A. The International Labour Organization: Its Work for Social and Economic Progress (London, 1970)

- Manwaring, J. International Labour Organization: A Canadian View (Ottawa, 1986)

- Morse, David. The Origin and Evolution of the ILO and its Role in the World Community (Ithaca, 1969)

- Morse, David. "International Labour Organization – Nobel Lecture: ILO and the Social Infrastructure of Peace"

- Ostrower, Gary B. "The American decision to join the international labor organization", Labor History, Volume 16, Issue 4 Autumn 1975, pp 495–504 The U.S. joined in 1934

- VanDaele, Jasmien. "The International Labour Organization (ILO) In Past and Present Research," International Review of Social History 2008 53(3): 485–511, historiography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to International Labour Organization. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article "International Labour Organization". |