John Witherspoon

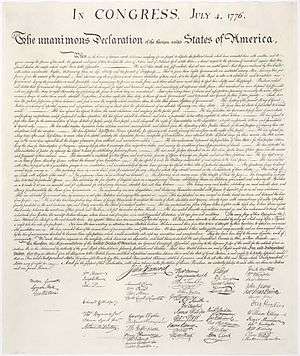

John Witherspoon (February 5, 1723 – November 15, 1794) was a Scottish-American Presbyterian minister and a Founding Father of the United States.[1] Witherspoon embraced the concepts of Scottish common sense realism, and while president of the College of New Jersey (1768–1794; now Princeton University), became an influential figure in the development of the United States' national character. Politically active, Witherspoon was a delegate from New Jersey to the Second Continental Congress and a signatory to the July 4, 1776, Declaration of Independence. He was the only active clergyman and the only college president to sign the Declaration.[2] Later, he signed the Articles of Confederation and supported ratification of the Constitution. In 1789 he was convening moderator of the First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America.

John Witherspoon | |

|---|---|

%2C_President_(1768-94).jpg) | |

| Born | John Witherspoon February 5, 1723 |

| Died | November 15, 1794 (aged 72) Near Princeton, New Jersey, US |

| Resting place | Princeton Cemetery |

| Nationality | American/Scottish |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Clergyman and theologian |

| Signature | |

Early life and ministry in Scotland

John Witherspoon[3] was born in Gifford, East Lothian, Scotland, as the eldest child of the Reverend James Alexander Witherspoon and Anne Walker,[4] a descendant of John Welsh of Ayr and John Knox.[5] This latter claim of Knox descent though ancient in origin is long disputed and without primary documentation.[6] He attended the Haddington Grammar School, and obtained a Master of Arts from the University of Edinburgh in 1739. He remained at the university to study divinity.[7] In 1764, he was awarded an honorary doctoral degree in divinity by the University of St. Andrews.[8]

Witherspoon was a staunch Protestant, nationalist, and supporter of republicanism. Consequently, he was opposed to the Roman Catholic Legitimist Jacobite rising of 1745–46. Following the Jacobite victory at the Battle of Falkirk (1746), he was briefly imprisoned at Doune Castle,[9] which had a long-term effect on his health.

He became a Church of Scotland (Presbyterian) minister at Beith, Ayrshire (1745–1758), where he married Elizabeth Montgomery of Craighouse. They had ten children, with five surviving to adulthood.

From 1758 to 1768, he was minister of the Laigh kirk, Paisley (Low Kirk). Witherspoon became prominent within the Church as an Evangelical opponent of the Moderate Party.[10] During his two pastorates he wrote three well-known works on theology, notably the satire "Ecclesiastical Characteristics" (1753),[11] which opposed the philosophical influence of Francis Hutcheson.[12]

Princeton

At the urging of Benjamin Rush and Richard Stockton, whom he met in Paisley,[13] Witherspoon finally accepted their renewed invitation (having turned one down in 1766) to become president and head professor of the small Presbyterian College of New Jersey in Princeton.[14] Thus, Witherspoon and his family emigrated to New Jersey in 1768.

At the age of 45, he became the sixth president of the college, later known as Princeton University. Upon his arrival, Witherspoon found the school in debt, with weak instruction, and a library collection which clearly failed to meet student needs. He immediately began fund-raising—locally and back home in Scotland—added three hundred of his own books to the library, and began purchasing scientific equipment including the Rittenhouse orrery, many maps, and a terrestrial globe.

Witherspoon also instituted a number of reforms, including modeling the syllabus and university structure after that used at the University of Edinburgh and other Scottish universities. He also firmed up entrance requirements, which helped the school compete with Harvard and Yale for scholars.

Witherspoon personally taught courses in eloquence or belles lettres, chronology (history), and divinity. However, none was more important than moral philosophy (a required course). An advocate of natural law within a Christian and republican cosmology, Witherspoon considered moral philosophy vital for ministers, lawyers, and those holding positions in government (magistrates). Firm but good-humored in his leadership, Witherspoon was very popular among both faculty and students.

Witherspoon had been a prominent evangelical Presbyterian minister in Scotland before accepting the Princeton position. As the college's primary occupation at the time was training ministers, Witherspoon became a major leader of the early Presbyterian Church in America. He also helped organize Nassau Presbyterian Church in Princeton, New Jersey.

Nonetheless, Witherspoon transformed a college designed predominantly to train clergymen into a school that would equip the leaders of a new Protestant country. Students who later played prominent roles in the new nation's development included James Madison, Aaron Burr, Philip Freneau, William Bradford, and Hugh Henry Brackenridge.[15] From among his students came 37 judges (three of whom became justices of the U.S. Supreme Court); 10 Cabinet officers; 12 members of the Continental Congress, 28 U.S. senators, and 49 United States congressmen.

Revolutionary War

%2C_by_John_Trumbull.jpg)

Long wary of the power of the British Crown, Witherspoon saw the growing centralization of government, progressive ideology of colonial authorities, and establishment of Episcopacy authority as a threat to the Liberties of the colonies. Of particular interest to Witherspoon was the crown's growing interference in the local and colonial affairs which previously had been the prerogatives and rights of the American authorities. When the crown began to give additional authority to its appointed Episcopacy over Church affairs, British authorities hit a nerve in the Presbyterian Scot, who saw such events in the same lens as his Scottish Covenanters. Soon, Witherspoon came to support the Revolution, joining the Committee of Correspondence and Safety in early 1774. His 1776 sermon "The Dominion of Providence over the Passions of Men" was published in many editions and he was elected to the Continental Congress as part of the New Jersey delegation,[17] appointed Congressional Chaplain by the President of the Continental Congress John Hancock, and in July 1776, voted to adopt the Virginia Resolution for Independence. In answer to an objection that the country was not yet ready for independence, according to tradition he replied that it "was not only ripe for the measure, but in danger of rotting for the want of it." He lost his son Major James during the Battle of Germantown in 1777.[18][19][20]

Witherspoon served in Congress from June 1777 until November 1784 and became one of its most influential members and a workhorse of prodigious energy. He served on over 10,000 committees, most notably the sitting committees, the board of peace and the committee on public correspondence or common affairs. He spoke often in concurrence; helped draft the Articles of Confederation; helped organize the executive departments; played a major role in shaping public policy; and drew up the instructions for the peace commissioners. He fought against the flood of paper money, and opposed the issuance of bonds without provision for their amortization. "No business can be done, some say, because money is scarce", he wrote. He also served twice in the New Jersey Legislature, and strongly supported the adoption of the United States Constitution during the New Jersey ratification debates.

In November 1777, American forces neared, Witherspoon closed and evacuated the College of New Jersey. The main building, Nassau Hall, was badly damaged and his papers and personal notes were lost. Witherspoon was responsible for its reconstruction after the war, which caused him great personal and financial difficulty. In 1780 he was elected to a one-year term in the New Jersey Legislative Council representing Somerset County. At the age of 68, he married a 24-year-old widow, with whom he had two more children.[21]

Death and burial

Witherspoon suffered eye injuries and was blind by 1792. He died in 1794 on his farm Tusculum, just outside Princeton, and is buried along Presidents Row in Princeton Cemetery.[22] An inventory of Witherspoon's possessions taken at his death included "two slaves ... valued at a hundred dollars each".[23]

Family

Witherspoon and his wife, Elizabeth Montgomery, had a total of 10 children, only five of whom survived to accompany their parents to America. James, the eldest, a young man of great promise, graduated from Princeton in 1770, and joined the American army as an aide to General Francis Nash, with the rank of major. The next youngest son, John, graduated from Princeton in 1779, practiced medicine in South Carolina, and was lost at sea in 1795. David, the youngest son, graduated the same year as his brother, married the widow of Abner Nash, brother of General Francis Nash, and practiced law in New Bern, North Carolina. Anna, the eldest daughter, married Reverend Samuel Smith on June 28, 1775. Reverend Samuel Smith succeeded Dr. Witherspoon as president of Princeton in 1775. Frances, the youngest daughter, married Dr. David Ramsay, a delegate from South Carolina to the Continental Congress, on March 18, 1763. Witherspoon is claimed to be an ancestor of actress Reese Witherspoon.[24]

Philosophy

According to Herbert Hovenkamp, Witherspoon’s most lasting contribution was the initiation of the Scottish common sense realism, which he had learned by reading Thomas Reid and two of his expounders Dugald Stewart and James Beattie.[25]

Witherspoon revised the moral philosophy curriculum, strengthened the college's commitment to natural philosophy, and positioned Princeton in the larger transatlantic world of the republic of letters. Witherspoon was a proponent of Christian values, his common sense approach to the public morality of civil magistrates was influenced by the ethics of Scottish philosophers Francis Hutcheson and Thomas Reid rather than Jonathan Edwards. In regard to civil magistrates, Witherspoon thus believed moral judgment should be pursued as a science. He held to old concepts from the Roman Republic of virtuous leadership by civil magistrates, but he also regularly recommended that his students read such modern philosophers as Machiavelli, Montesquieu, and David Hume, even though he disapproved of Hume's "infidel" stance on religion.

Virtue, he argued, could be deduced through the development of the moral sense, an ethical compass instilled by God in all human beings and developed through religious education (Reid) or civil sociability (Hutcheson). Witherspoon saw morality as having two distinct components: spiritual and temporal. Civil government owed more to the latter than the former in Witherspoon's Presbyterian doctrine. Thus, public morality owed more to the natural moral laws of the Enlightenment than to revealed Christianity.

In his lectures on moral philosophy at Princeton, required of all juniors and seniors, Witherspoon argued for the revolutionary right of resistance and recommended checks and balances within government. He made a profound impression on his student James Madison, whose suggestions for the United States Constitution followed both Witherspoon's and Hume's ideas. The historian Douglass Adair writes, "The syllabus of Witherspoon's lectures . . . explains the conversion of the young Virginian to the philosophy of the Enlightenment."[26]

Witherspoon accepted the impossibility of maintaining public morality or virtue in the citizenry without an effective religion. In this sense, the temporal principles of morality required a religious component which derived its authority from the spiritual. Therefore, public religion was a vital necessity in maintaining the public morals. However, in this framework, non-Christian societies could have virtue, which, by his definition, could be found in natural law. Witherspoon, in accordance with the Scottish moral sense philosophy, taught that all human beings, Christian or otherwise, could be virtuous, but he was nonetheless committed to Christianity as the only route to personal salvation.

Witherspoon owned slaves and lectured against the abolition of slavery.[27]

Legacy

Apologist of Reformed Christianity

John Witherspoon is not known for being a particularly insightful, significant, or even consistent Reformed preacher and thinker. However, he was firmly grounded in the Reformed tradition of High to Late Orthodoxy, embedded in the transatlantic Evangelical Awakening of the eighteenth century, and frustrated by the state of religion in the Scottish Kirk. Like Benedict Pictet (1655-1724), Witherspoon held firmly to the tenets of confessional Calvinism. And like Pictet, Witherspoon was eager to show that the truths of supernatural revelation could be squared with reason. His aim as a minister was to defend and rearticulate traditional Scottish Presbyterian theology, without altering or disguising it.[28]

Statues

- Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey[29]

- Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia

- University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, Scotland, United Kingdom

- Doctor John Witherspoon, Connecticut Avenue and N Street, N.W., near Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C.[30]

Buildings

- Witherspoon Hall, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey[31]

- John Witherspoon Middle School, Princeton, New Jersey

- Witherspoon Building, in the Market East neighborhood of Philadelphia[32]

- The former Witherspoon Street School for Colored Children, Princeton, New Jersey

Other

- John Witherspoon College, a non-denominational Christian liberal arts[33] college in Rapid City, South Dakota

- Witherspoon Institute, a research center, in Princeton, New Jersey[34]

- Witherspoon Society, an organization of laypeople within the Presbyterian Church (USA)[35]

- Witherspoon Street, in: Princeton, New Jersey; Louisville, Kentucky; and, Paisley, Scotland

- SS John Witherspoon, a Liberty ship class United States Merchant Marine ship during World War II; participated in an Allied convoy, code named PQ 17, and was sunk in the Barents Sea by the German submarine U-255 on July 6, 1942

- Portrayed in the musical 1776, about the debates over and eventual adoption of the Declaration of Independence, by Edmund Lyndeck in the 1969 stage play and by James Noble in the 1972 film

References

Citations

- Longfield, Bradley J. (2013). Presbyterians and American Culture: A History. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9780664231569. Retrieved November 6, 2015..

- "Princeton Presidents". Princeton University. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- Pyne, F. W. Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. 3 Pt. 1 (2nd ed.). Rockport, Maine: Picton press. p. 93.

- Witherspoon's mother's name has alternatively been spelled as "Anna Walker".

- Maclean, John, Jr. (1877). History of the College of New Jersey: From Its Origin in 1746 to the Commencement of 1854. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. Vol. 1, p384.

- Waters (1910). Witherspoon, Knox. The New England historical and genealogical register, Volume 64. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- "John Witherspoon". ushistory.org. Independence Hall Association. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- Tait, L. Gordon (2001). The Piety of John Witherspoon: Pew, Pulpit, and Public Forum. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0664501334.

- "John Witherspoon". The History of the Presbyterian Church. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- Herman, Arthur (2003). The Scottish Enlightenment. Fourth Estate. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-84115-276-9.

- Witherspoon, John, 1723-1794 (October 7, 2015). The selected writings of John Witherspoon. Miller, Thomas P. Carbondale: Landmarks in Rhetoric and Public Address. pp. 57–102. ISBN 978-0-8093-9054-0. OCLC 926709851.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Macintyre, Alasdair (1988). Whose Justice? Which Rationality?. Duckworth. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-7156-2199-8.

- Rampant Scotland "Rampant Scotland, John Witherspoon"

- Rush and Stockton's recruiting letters can be found in Butterfield, L. H., "John Witherspoon Comes to America", Princeton University Library, Princeton, New Jersey. 1953

- Jeffry H. Morrison, John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic (2005)

- americanrevolution.org Key to Trumbull's picture

- Herman, Arthur (2003). The Scottish Enlightenment. Fourth Estate. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-84115-276-9.

- Proceedings and Collections, Wyoming Historical Society

- The Battle of Germantown

- The Piety of John Witherspoon

- "Witherspoon, John". etcweb.princeton.edu.

- History of Princeton and its Institutions

- Knowlton, Steven. "LibGuides: African American Studies: Slavery at Princeton". libguides.princeton.edu. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- MacLean, Maggie. "Elizabeth Montgomery Witherspoon". History of American Women. History of American Women. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- Science and Religion in America, 1800–1860, Herbert Hovenkamp, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978 ISBN 0-8122-7748-1 pp. 5, 9

- Adair, "James Madison", Fame and the Founding Fathers, ed. Trevor Colbourn (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1974) 181.

- Redmond, Lesa. "John Witherspoon". slavery.princeton.edu. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Kruger, Michael J. (January 28, 2019). "Congratulations to Dr. Kevin DeYoung". Canon Fodder. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- Princeton University "Statue Unveiling"

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Who Is That Man, Anyway?

- "Witherspoon Hall". etcweb.princeton.edu.

- "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Note: This includes Richard J. Webster (July 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Witherspoon Building" (PDF). Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- "Liberal Arts? Are You Kidding? Archived 2015-04-09 at the Wayback Machine" John Witherspoon College

- The Witherspoon Institute Archived 2010-04-10 at the Wayback Machine

- "Welcome witherspoonsociety.org - BlueHost.com". www.witherspoonsociety.org.

Sources

- Burns, David G. C. (December 2005). "The Princeton Connection". The Scottish Genealogist. 52 (4). ISSN 0300-337X.

- Collins, Varnum L. President Witherspoon: A Biography, 2 vols. (1925, repr. 1969)

- Ashbel Green, ed. The Works of the Rev. John Witherspoon, 4 vols. (1802, repr. with a new introduction by L. Gordon Tait, 2003)

- Morrison, Jeffrey H. John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic (2005)

- Pomfret, John E.. '"Witherspoon, John" in Dictionary of American Biography (1934)

- Tait, L. Gordon. The Piety of John Witherspoon: Pew, Pulpit, and Public Forum (2001)

- Moses Coit Tyler "President Witherspoon in the American Revolution" The American Historical Review Volume 1, Issue 1, July 1896. pp. 671–79.

- Woods, David W.. John Witherspoon (1906)

- An Animated Son of Liberty – A life of John Witherspoon J. Walter McGinty (2012)

Further reading

- Tyler, Moses Coit (1963) [1895-1896]. Jameson, J. Franklin (ed.). John Witherspoon. New York: Kraus Reprints / The American historical review. pp. 671–679.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Witherspoon |

- Biography on Princeton University's website

- United States Congress. "John Witherspoon (id: W000660)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Works by John Witherspoon at Post-Reformation Digital Library

- Photographic tour of John Witherspoon's grave at Princeton Cemetery.

- Biography by Rev. Charles A. Goodrich, 1856

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Samuel Finley |

President of the College of New Jersey 1768–1794 |

Succeeded by Samuel Stanhope Smith |

| Religious titles | ||

| New office | Convening Moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America 1789 |

Succeeded by John Rodgers |