Gilbert Stuart

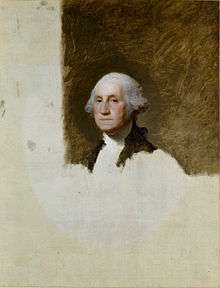

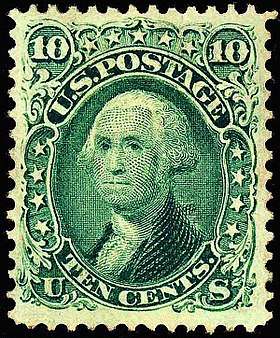

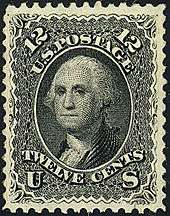

Gilbert Charles Stuart (born Stewart; December 3, 1755 – July 9, 1828) was an American painter from Rhode Island Colony who is widely considered one of America's foremost portraitists.[2] His best known work is the unfinished portrait of George Washington, begun in 1796, that is sometimes referred to as the Athenaeum Portrait. Stuart retained the portrait and used it to paint scores of copies that were commissioned by patrons in America and abroad. The image of George Washington featured in the painting has appeared on the United States one-dollar bill for more than a century[2] and on various postage stamps of the 19th century and early 20th century.[3]

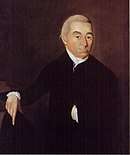

Gilbert Stuart | |

|---|---|

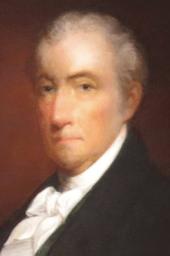

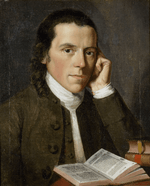

Portrait of Gilbert Stuart by Sarah Goodridge, 1825 | |

| Born | Gilbert Charles Stewart[1] December 3, 1755 |

| Died | July 9, 1828 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | George Washington (The Athenaeum Portrait) (1796) George Washington (Lansdowne portrait) (1796) George Washington (Vaughan Portrait) (1795) The Skater (1782) Catherine Brass Yates (1794) John Adams (1824) |

Stuart produced portraits of more than 1,000 people, including the first six Presidents.[4] His work can be found today at art museums throughout the United States and the United Kingdom, most notably the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Frick Collection in New York City, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the National Portrait Gallery, London, Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[5]

Biography

Early life

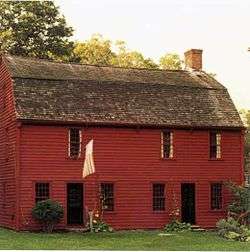

Gilbert Stuart was born on December 3, 1755, in Saunderstown, a village of North Kingstown in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, and he was baptized at Old Narragansett Church on April 11, 1756.[6][7] He was the third child of Gilbert Stewart,[8] a Scottish immigrant employed in the snuff-making industry, and Elizabeth Anthony Stewart, a member of a prominent land-owning family from Middletown, Rhode Island.[4] Stuart's father owned the first snuff mill in America, which was located in the basement of the family homestead.[9]

Stuart moved to Newport, Rhode Island at the age of six, where his father pursued work in the merchant field. In Newport, he first began to show great promise as a painter.[10] In 1770, he made the acquaintance of Scottish artist Cosmo Alexander, a visitor to the colonies who made portraits of local patrons and who became a tutor to Stuart.[11][12] Under the guidance of Alexander, Stuart painted the portrait Dr. Hunter's Spaniels when he was 14; it hangs today in the Hunter House Mansion in Newport.[7]

In 1771, Stuart moved to Scotland with Alexander to finish his studies; however, Alexander died in Edinburgh one year later. Stuart tried to maintain a living and pursue his painting career, but to no avail, so he returned to Newport in 1773.[13]

England and Ireland

Stuart's prospects as a portraitist were jeopardized by the onset of the American Revolution and its social disruptions. He was a Loyalist[14] and departed for England in 1775 following the example set by John Singleton Copley.[15] His painting style during this period began to develop beyond the relatively hard-edged and linear style that he had learned from Alexander.[16] He was unsuccessful at first in pursuit of his vocation, but he became a protégé of Benjamin West in 1777 and studied with him for the next six years. The relationship was beneficial, with Stuart exhibiting for the first time at the Royal Academy in spring of 1777.[17]

By 1782, Stuart had met with success, largely due to acclaim for The Skater, a portrait of William Grant. It was Stuart's first full-length portrait and, according to art historian Margaret C. S. Christman, it "belied the prevailing opinion that Stuart 'made a tolerable likeness of a face, but as to the figure, he could not get below the fifth button'".[18] Stuart said that he was "suddenly lifted into fame by a single picture".[19]

At one point, the prices for his pictures were exceeded only by those of renowned English artists Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Despite his many commissions, however, he was habitually neglectful of finances and was in danger of being sent to debtors' prison. In 1787, he fled to Dublin, Ireland where he painted and accumulated debt with equal vigor.[20]

New York and Philadelphia

Stuart ended his 18-year stay in Britain and Ireland in 1793, leaving behind numerous unfinished paintings. He returned to the United States with a particular goal in mind: to paint a portrait of George Washington, have an engraver reproduce it, and provide for his family by the sale of the engravings.[21] He settled briefly in New York City and pursued portrait commissions from influential people who could bring him to Washington's attention.[17] In 1794, he painted statesman John Jay, from whom he received a letter of introduction to Washington. In 1795, Stuart moved to Germantown, Philadelphia where he opened a studio,[22][23] and Washington posed for him later that year.[17]

.jpg)

Stuart painted Washington in a series of iconic portraits, each of them leading to a demand for copies and keeping him busy and highly paid for years.[24] The most famous and celebrated of these likenesses is known as The Athenaeum and is portrayed on the United States one-dollar bill. Stuart painted about 75 reproductions of The Athenaeum.[25] However, he never completed the original version; after finishing Washington's face, he kept the original version to make the copies.[26] He sold up to 70 of his reproductions for a price of $100 each, but the original portrait was left unfinished at the time of his death in 1828.[26] The painting was jointly purchased by the National Portrait Gallery and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1980, and is generally on display in the National Portrait Gallery.[27][28]

Another celebrated image of Washington is the Lansdowne portrait, a large portrait with one version hanging in the East Room of the White House. This painting was rescued during the Burning of Washington in the War of 1812 thanks to the efforts of First Lady Dolley Madison and Paul Jennings, one of President James Madison's slaves. Four versions of the portrait are attributed to Stuart,[29] and additional copies were painted by other artists for display in U.S. government buildings.[30] In 1803, Stuart opened a studio in Washington, D. C.[31]

Boston, 1805–1828

Stuart moved to Devonshire Street in Boston in 1805, continuing in both critical acclaim and financial troubles.[32] He exhibited works locally at Doggett's Repository[33] and Julien Hall.[34] He was sought out for advice by other artists, such as John Trumbull, Thomas Sully, Washington Allston, and John Vanderlyn.[18]

Personal life

Stuart married Charlotte Coates around September 1786; she was 13 years his junior and "exceedingly pretty".[35] They had 12 children, five of whom died by 1815 and two others died while they were young. Their daughter Jane (1812–1888) was also a painter. She sold many of his paintings and her replicas of them from her studios in Boston and Newport, Rhode Island.[36] In 2011, she was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame.[37]

In 1824, he suffered a stroke which left him partially paralyzed, but he still continued to paint for two years until his death in Boston on July 9, 1828, at 72.[38] He was buried in the Old South Burial Ground of the Boston Common.

Stuart left his family deeply in debt, and his wife and daughters were unable to purchase a grave site. He was, therefore, buried in an unmarked grave which was purchased cheaply from Benjamin Howland, a local carpenter.[39] His family recovered from their financial troubles 10 years later, and they planned to move his body to a family cemetery in Newport. However, they could not remember the exact location of his body, and it was never moved.[40] There is a monument for Stuart, his wife, and their children at the Common Burying Ground in Newport.[41]

The Boston Athenæum held a benefit exhibition of Stuart's works in August 1828 in an effort to provide financial aid for his family. More than 250 portraits were lent for this critically acclaimed and well-subscribed exhibition. This also marked the first public showing of his unfinished 1796 Athenæum Head portrait of Washington.[42]

Legacy

By the end of his career, Gilbert Stuart had painted the likenesses of more than 1,000 American political and social figures.[43] He was praised for the vitality and naturalness of his portraits, and his subjects found his company agreeable. John Adams said:

Speaking generally, no penance is like having one's picture done. You must sit in a constrained and unnatural position, which is a trial to the temper. But I should like to sit to Stuart from the first of January to the last of December, for he lets me do just what I please, and keeps me constantly amused by his conversation.[44]

Stuart was known for working without the aid of sketches, beginning directly upon the canvas, which was very unusual for the time period. His approach is suggested by the advice which he gave to his pupil Matthew Harris Jouett: "Never be sparing of colour, load your pictures, but keep your colours as separate as you can. No blending, tis destruction to clear & bea[u]tiful effect."[18]

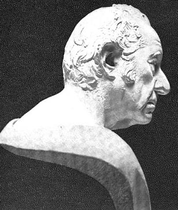

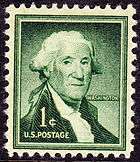

John Henri Isaac Browere created a life mask of Stuart around 1825.[45] In 1940, the U.S. Post Office issued a series of postage stamps called the "Famous Americans Series" commemorating famous artists, authors, inventors, scientists, poets, educators, and musicians. Gilbert Stuart is found on the 1 cent issue in the artists category, along with James McNeil Whistler, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Daniel Chester French, and Frederic Remington.

Today, Stuart's birthplace in Saunderstown, Rhode Island is open to the public as the Gilbert Stuart Birthplace and Museum. The museum consists of the original house where he was born, with copies of his paintings hanging throughout the house. The museum opened in 1930.[46]

- Memorial tablet located in the Boston Common

John H. I. Browere's life mask portrait of Stuart, c. 1825

John H. I. Browere's life mask portrait of Stuart, c. 1825

Gilbert Stuart Issue of 1940

Gilbert Stuart's paintings of Washington, Jefferson, and others have served as models for dozens of U.S. postage stamps. Washington's image from the famous portrait The Athenaeum is probably the most noted example of Stuart's work on postage.

1861

1861 1861

1861 1903

1903 1954

1954

Notable people painted

This is a partial list of portraits painted by Stuart.[47]

- Abigail Adams – Second First Lady of the United States, wife of John Adams

- John Adams – Second President of the United States

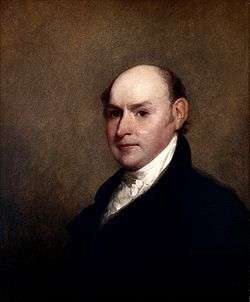

- John Quincy Adams – Sixth President of the United States

- Charles Humphrey Atherton - United States Representative from New Hampshire from 1815-1817

- John Jacob Astor – First American multi-millionaire, fur trader, art patron

- John Bannister – Owner of Bannister's Wharf in Newport, Rhode Island

- Commodore John Barry – Father of the American Navy

- Ann Willing Bingham – Philadelphia socialite

- Horace Binney – Prominent Philadelphia lawyer

- Elizabeth Bowdoin, Lady Temple – wife of Sir John Temple, first British consul general to United States, 1785[48]

- Hugh Henry Brackenridge – early American writer, Pennsylvania Supreme Court justice, and founder of the University of Pittsburgh[49]

- Jean Baptiste Casmiere Breschard – Performer and theatrical impresario

- Rosalie Stier Calvert – Belgian-born heiress and mother of Charles Benedict Calvert

- Mary Willing Clymer – Philadelphia socialite

- John Singleton Copley – American colonial portraitist

- Thomas Dawes - Early American architect, builder, military leader, politician

- Horatio Gates – American Revolutionary War general

- King George III – King of United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, 1760–1820

- King George IV – King of United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, 1820–30

- John Jay – First Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court

- Thomas Jefferson – Third President of the United States

- Rufus King – a signer of United States Constitution

- Robert Kingsmill – Admiral in Royal Navy during American and French Revolutionary Wars

- King Louis XVI – King of France, 1774–92

- James Madison – Fourth President of the United States

- Samuel Miles – Revolutionary War General and Philadelphia mayor

- James Monroe – Fifth President of the United States

- Daniel Pinckney Parker – Prominent Boston merchant

- John Randolph of Roanoke – Virginia congressman and senator[49]

- Joshua Reynolds – English artist

- Henry Rice – Boston merchant and Massachusetts state legislator[49]

- John Tayloe III – Virginia planter, builder of The Octagon House in Washington, DC.

- Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney – the cities of Sydney in New South Wales and Sydney, Nova Scotia are named in his honor[49]

- John Trumbull – artist during the period of the American Revolutionary War

- George Washington – First President of the United States

- Martha Washington – First Lady of the United States, wife of George Washington

- Benjamin West – American painter

- Catherine Brass Yates – Philadelphia socialite

- John Bill Ricketts – Equestrian, leader of Ricketts' Circus in Philadelphia

Portrait gallery

John Banister, Jr., 1774–75

John Banister, Jr., 1774–75 Christian Stelle Banister and Son, 1774

Christian Stelle Banister and Son, 1774 Jacob Rodriguez Rivera, c. 1775

Jacob Rodriguez Rivera, c. 1775 Benjamin Waterhouse, 1775

Benjamin Waterhouse, 1775 American artist Benjamin West, 1783–84

American artist Benjamin West, 1783–84 English artist Joshua Reynolds, 1784

English artist Joshua Reynolds, 1784 American artist John Singleton Copley, c. 1784

American artist John Singleton Copley, c. 1784 John Jones of Frankley, 1785, Birmingham Museum of Art

John Jones of Frankley, 1785, Birmingham Museum of Art Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, 1785, British Museum, London

Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, 1785, British Museum, London Robert R. Livingston, diplomat and Founding Father, 1793–94

Robert R. Livingston, diplomat and Founding Father, 1793–94.jpg) John Jay, 1794, First Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court

John Jay, 1794, First Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court William Bayard, 1794, Princeton University Art Museum

William Bayard, 1794, Princeton University Art Museum

Peter Gansevoort, 1794

Peter Gansevoort, 1794

George Washington, 1795, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York

George Washington, 1795, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York.jpg) Lansdowne portrait of George Washington, 1797

Lansdowne portrait of George Washington, 1797 George Washington (The Constable-Hamilton Portrait, 1797) Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

George Washington (The Constable-Hamilton Portrait, 1797) Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas portrait of George Washington's chef, c.1797

portrait of George Washington's chef, c.1797 George Gibbs, 1798, Newport Art Museum, Rhode Island

George Gibbs, 1798, Newport Art Museum, Rhode Island Anna Payne Cutts, sister of First Lady Dolley Madison, 1804, The White House

Anna Payne Cutts, sister of First Lady Dolley Madison, 1804, The White House The fourth President of the United States, James Madison, 1804, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

The fourth President of the United States, James Madison, 1804, Bowdoin College Museum of Art Jérôme Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, 1804

Jérôme Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, 1804 George Calvert, politician and planter, 1804

George Calvert, politician and planter, 1804 Rosalie Stier Calvert, Belgian-born heiress and wife of George Calvert

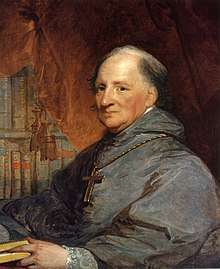

Rosalie Stier Calvert, Belgian-born heiress and wife of George Calvert John Carroll, first Catholic bishop of the United States, c. 1804, Georgetown University Art Collection, Washington, D.C.

John Carroll, first Catholic bishop of the United States, c. 1804, Georgetown University Art Collection, Washington, D.C. George Washington At Dorchester Heights, 1806, Boston Museum of Fine Arts

George Washington At Dorchester Heights, 1806, Boston Museum of Fine Arts Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis, 1809, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC

Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis, 1809, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, NC The second First Lady of the United States, Abigail Adams, c. 1800–1815

The second First Lady of the United States, Abigail Adams, c. 1800–1815 Major-General Henry Dearborn 1812-1815[?]

Major-General Henry Dearborn 1812-1815[?] Henry Rice, Boston merchant and Massachusetts state legislator, c. 1815

Henry Rice, Boston merchant and Massachusetts state legislator, c. 1815 American artist John Trumbull, c. 1818

American artist John Trumbull, c. 1818 The sixth President of the United States, John Quincy Adams, 1818

The sixth President of the United States, John Quincy Adams, 1818 The third President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, c. 1821, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The third President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, c. 1821, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. The fourth President of the United States, James Madison, c. 1821, National Gallery of Art

The fourth President of the United States, James Madison, c. 1821, National Gallery of Art The fifth President of the United States, James Monroe, c. 1820–1822

The fifth President of the United States, James Monroe, c. 1820–1822 The second President of the United States, John Adams, 1826

The second President of the United States, John Adams, 1826 The sixth First Lady of the United States, Louisa Catherine Adams c. 1821–26, daughter-in law of John and Abigail Adams

The sixth First Lady of the United States, Louisa Catherine Adams c. 1821–26, daughter-in law of John and Abigail Adams

References

- "Gilbert Stuart (1775–1828)". Worcester Art Museum. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- Gilbert Stuart Birthplace and Museum. Gilbert Stuart Biography. Accessed July 24, 2007.

- "10-cent Washington". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- "Gilbert Stuart Birthplace". Archived from the original on November 16, 2005. Retrieved October 10, 2010.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link), The Story of Gilbert Stuart. Woonsocket Connection. Retrieved on July 25, 2007.

- Gilbert Stuart. ArtCyclopedia. Paintings in Museums and Public Art Galleries. Accessed July 24, 2007.

- The Old Narragansett Church (St. Paul's): Built A.D. 1707. A Constant Witness to Christ and His Church. Committee of Management. 1915. p. 15. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- "Gilbert Stuart". The Gilbert Stuart Museum. Archived from the original on October 6, 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- "Gilbert Stuart". NNDB. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- McLanathan 1986, p. 13.

- Gilbert Stuart Birthplace Archived August 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Gilbert Stuart. Accessed: July 28, 2007.

- "Gilbert Stuart, Newport and Edinburgh (1755–1775)". National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on September 3, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- "Gilbert Stuart". Redwood Library and Athenæum, Newport Rhode Island. Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- "Gilbert Stuart". Germantown, Portrait Artist. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- Park et al. (1926), p. 26.

- National Gallery of Art Archived September 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Gilbert Stuart. London (1775–1787). Accessed: July 31, 2007.

- National Gallery of Art. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- Christman, M., & Barlow, M. (2003). Stuart [Stewart], Gilbert. Grove Art Online. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- Christman, Margaret C. S. "Stuart, Gilbert." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, retrieved October 1, 2012

- National Gallery of Art Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.The Skater (Portrait of William Grant), 1782. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- National Gallery of Art Archived June 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Gilbert Stuart. Dublin (1787–1793). Accessed: July 31, 2007.

- Park et al. (1926), p. 44.

- "Gilbert Stuart – Washington". americanrevolution.org. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- "George Washington". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- National Gallery of Art Archived April 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Gilbert Stuart. Philadelphia (1794–1803). Accessed: July 31, 2007.

- "George Washington Portrait by Gilbert Stuart", www.mountvernon.org. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- Wallechinsky, David and Irving Wallace. "Unfinished Art: Gilbert Stuart's Portrait of George Washington". The People's Almanac. Trivia-Library.com. Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, George Washington Accessed December 12, 2014.

- National Portrait Gallery Collections Search, p. 9. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- Stretch, Bonnie Barrett, "The White House Washington", Artnews, October 1, 2004. Accessed: May 11, 2012.

- Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives, Artist Gilbert Stuart's portraits of George Washington. Archived September 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Accessed: May 11, 2012.

- National Gallery of Art Archived June 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Gilbert Stuart. Washington, D.C. (1803–1805). Accessed: July 31, 2007.

- The Boston Directory. Boston: E. Cotton. 1813. p. 237.

- Daily Advertiser, March 2, 1822

- Boston Commercial Gazette December 1, 1825

- Dorinda Evans (January 1, 2013). Gilbert Stuart and the Impact of Manic Depression. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4094-4164-9.

- "History Bytes: Jane Stuart". Newport Historical Society. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- Patrick T. Conley (2011). "Jane Stuart". Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- McLanathan 1986, p. 148.

- McLanathan 1986, p. 150.

- Wolpaw, Jim. Gilbert Stuart: A Portrait from Life (9-Minute Trailer). Documentary.

- "Jane Stuart". Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Commission. 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- Swan, Mabel Munson The Athenæum Gallery 1827–1873: The Boston Athenæum as an Early Patron of Art (Boston: The Boston Athenæum, 1940) pp. 62–73

- "Gilbert Stuart". Gilbert Stuart Museum. Archived from the original on October 6, 2010. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- McLanathan 1986, p. 147.

- Charles Henry Hart. Browere's life masks of great Americans. Printed at the De Vinne Press for Doubleday and McClure Company, 1899. Internet Archive

- "Gilbert Stuart Birthplace and Museum". Gilbert Stuart Museum. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- Mason 1879, pp. 125–283.

- "Elizabeth Bowdoin". National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- Mantle 1929.

Bibliography

- Fielding, Mantle (1929). "Paintings by Gilbert Stuart not mentioned in Mason's Life of Stuart". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. 53 (2). JSTOR 20086696.

- McLanathan, Richard (1986). Gilbert Stuart. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 9780810915015.

- Mason, George C. (1879). The Life and Works of Gilbert Stuart. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Park, Lawrence, John Hill Morgan, and Royal Cortissoz (1926). Gilbert Stuart : An Illustrated Descriptive List of His Works. New York: W. E. Rudge.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gilbert Stuart. |

- 50 paintings by or after Gilbert Stuart at the Art UK site

- Gilbert Stuart at the National Gallery of Art, Washington

- Gilbert Stuart Biography, National Gallery of Art

- Gilbert Stuart Museum Website

- Gilbert-Stuart.org 155 works by Gilbert Stuart

- Gilbert Stuart on ArtCyclopedia

- Union List of Artist Names, Getty Vocabularies. ULAN Full Record Display for Gilbert Stuart. Getty Vocabulary Program, Getty Research Institute. Los Angeles, California.

- Gilbert Stuart, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art