Covenant of the League of Nations

The Covenant of the League of Nations was the charter of the League of Nations. It was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

| Signed | 28 June 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Paris Peace Conference |

| Effective | 10 January 1920 |

| Expiration | April 20, 1946 |

| Expiry | July 31, 1947 |

| Parties | League of Nations members |

| Depositary | League of Nations |

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

|

Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye |

|

Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine |

|

Treaty of Trianon |

Creation

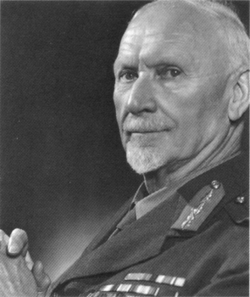

Early drafts for a possible League of Nations began even before the end of the First World War. The London-based Bryce Group made proposals adopted by the British League of Nations Society, founded in 1915.[1] Another group in the United States—which included Hamilton Holt and William B. Howland at the Century Association in New York City—had their own plan. This plan was largely supported by the League to Enforce Peace, an organization led by former U.S. President William Howard Taft.[1] In December 1916, Lord Robert Cecil suggested that an official committee be set up to draft a covenant for a future league. The British committee was finally appointed in February 1918; it was led by Walter Phillimore (and became known as the Phillimore Committee) but also included Eyre Crowe, William Tyrrell, and Cecil Hurst.[1] U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was not impressed with the Phillimore Committee's report, and would eventually produce three draft covenants of his own with help from his friend Colonel House. Further suggestions were made by Jan Christiaan Smuts in December 1918.[1]

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, a commission was appointed to agree on a covenant. Members included Woodrow Wilson (as chair), Colonel House (representing the U.S.), Robert Cecil and Jan Smuts (British Empire), Léon Bourgeois and Ferdinand Larnaude (France), Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando and Vittorio Scialoja (Italy), Foreign Minister Makino Nobuaki and Chinda Sutemi (Japan), Paul Hymans (Belgium), Epitácio Pessoa (Brazil), Wellington Koo (China), Jayme Batalha Reis (Portugal), and Milenko Radomar Vesnitch (Serbia).[2] Further representatives of Czechoslovakia, Greece, Poland and Romania were later added. The group considered a preliminary draft co-written by Hurst and President Wilson's adviser David Hunter Miller. During the first four months of 1919 the group met on ten separate occasions, attempting to negotiate the exact terms of the foundational Covenant agreement for the future League.

During the ensuing negotiations various major objections arose from various countries. France wanted the League to form an international army to enforce its decisions, but the British worried such an army would be dominated by the French, and the Americans could not agree as only Congress could declare war.[1] Japan requested that a clause upholding the principle of racial equality should be inserted, parallel to the existing religious equality clause. This was deeply opposed, particularly by American political sentiment, while Wilson himself simply ignored the question.

During a certain interval while Wilson was away, the question of international equality was raised once again. A vote on a motion supporting the "equality of nations and the just treatment of their nationals" was made, and was supported by 11 of the 19 delegates. Upon Wilson's return he declared that "serious objections" by other delegates had negated the majority vote, and the amendment was dismissed.[1] Finally on April 11, 1919, the revised Hurst-Miller draft was approved, but without fully resolving certain questions as had been brought forth regarding matters such as national equality, racial equality, and how the new League might be able to practically enforce its various mandates.[1]

The new League would include a General Assembly (representing all member states), an Executive Council (with membership limited to major powers), and a permanent secretariat. Member states were expected to "respect and preserve as against external aggression" the territorial integrity of other members, and to disarm "to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety". All states were required to submit complaints for arbitration or judicial inquiry before going to war.[1] The Executive Council would create a Permanent Court of International Justice to make judgements on the disputes.

The treaty entered into force on 10 January 1920. Articles 4, 6, 12, 13, and 15 were amended in 1924. The treaty shares similar provisions and structures with the UN Charter.[3]

Article X

Article X of the Covenant of the League of Nations is the section calling for assistance to be given to a member that experiences external aggression. It was signed by the major Peacemakers (Allied Forces) following the First World War, most notably Britain and France. Due to the nature of the Article, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was unable to ratify his obligation to join the League of Nations, as a result of strong objection from U.S. politicians.

Although Wilson had secured his proposal for a League of Nations in the final draft of the Treaty of Versailles, the U.S. Senate refused to consent to the ratification of the Treaty. For many Republicans in the Senate, Article X was the most objectionable provision. Their objections were based on the fact that, by ratifying such a document, the United States would be bound by international contract to defend a League of Nations member if it was attacked. Henry Cabot Lodge from Massachusetts and Frank B. Brandegee from Connecticut led the fight in the U.S. Senate against ratification, believing that it was best not to become involved in international conflicts. Under the United States Constitution, the President of the United States may not ratify a treaty unless the Senate, by a two-thirds vote, gives its advice and consent.

Article XXII

Article XXII referred to the creation of Mandate territories, i.e. territories which were given over to be administered by European powers. Though in most cases, Mandates were given to countries such as Britain and France, which possessed considerable colonial empires, the Covenant made the clear distinction that a Mandate Territory was not a colony.

The Covenant asserted that such territories were "inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world" and therefore "the tutelage of such peoples should be entrusted to advanced nations who by reason of their resources, their experience or their geographical position can best undertake this responsibility" as a "a sacred trust of civilization".

Mandate territories were sorted into several sub-categories:

- "Communities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire" were considered "to have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations could be provisionally recognized" and the Mandatory powers were charged with "rendering administrative advice and assistance until such time as they are able to stand alone".

- Regarding "Other peoples, especially those of Central Africa" the Mandatory powers were charged to "guarantee freedom of conscience and religion, subject only to the maintenance of public order and morals, the prohibition of abuses such as the slave trade, the arms traffic and the liquor traffic, and the prevention of the establishment of fortifications or military and naval bases and of military training of the natives for other than police purposes and the defence of territory", and no mention was made of any eventual independence.

- With regard to "Territories, such as South-West Africa and certain of the South Pacific Islands" were considered "owing to the sparseness of their population, or their small size, or their remoteness from the centres of civilisation, or their geographical contiguity to the territory of the Mandatory, and other circumstances" were assumed to be "best administered under the laws of the Mandatory as integral portions of its territory, subject to the safeguards above mentioned in the interests of the indigenous population". The reference to "geographical contiguity to the territory of the Mandatory" clearly related to South-West Africa (the present Namibia) being made a Mandate of South Africa rather than of Britain.

See also

References

- Northedge, F. S. (1986). The League of Nations: Its life and times, 1920–1946. Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-1194-8.

- Commission de la Société des Nations, Procès-verbal N° 1, Séance du 3 février 1919 (PDF), 3 February 1919, retrieved 5 January 2014

- League of Nations Covenant and United Nations Charter: A Side-by-Side (Full Text) Comparison by Walter Dorn

External links

![]()

- The Covenant of the League of Nations from the Yale Avalon Project

- Primary Documents: Covenant of the League of Nations, 1919–24 from FirstWorldWar.com