Bulgaria

Bulgaria (/bʌlˈɡɛəriə, bʊl-/ (![]()

Republic of Bulgaria | |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

Location of Bulgaria (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Sofia 42°41′N 23°19′E |

| Official languages | Bulgarian |

| Official script | Cyrillic |

| Ethnic groups (2011) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Bulgarian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Rumen Radev | |

| Boyko Borisov | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Establishment history | |

| 681–1018 | |

| 1185–1396 | |

| 3 March 1878 | |

| 5 October 1908 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 110,993.6[1] km2 (42,854.9 sq mi) (103rd) |

• Water (%) | 2.16[2] |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | |

• Density | 63/km2 (163.2/sq mi) (118th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2019) | medium |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 52nd |

| Currency | Lev (BGN) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| UTC+3 (EEST) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +359 |

| ISO 3166 code | BG |

| Internet TLD | .bg .бг |

One of the earliest societies in the lands of modern-day Bulgaria was the Neolithic Karanovo culture, which dates back to 6,500 BC. In the 6th to 3rd century BC the region was a battleground for ancient Thracians, Persians, Celts and Macedonians; stability came when the Roman Empire conquered the region in AD 45. The Eastern Roman Empire lost some of these territories to Slavic and then Turkic Bulgar invaders in the late 7th century. The Bulgars founded the First Bulgarian Empire in AD 681, which dominated most of the Balkans and significantly influenced Slavic cultures by developing the Cyrillic script. This state lasted until the early 11th century, when Byzantine emperor Basil II conquered and dismantled it. A successful Bulgarian revolt in 1185 established a Second Bulgarian Empire, which reached its apex under Ivan Asen II (1218–1241). After numerous exhausting wars and feudal strife, the empire disintegrated in 1396 and fell under Ottoman rule for nearly five centuries.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 resulted in the formation of the third and current Bulgarian state. Many ethnic Bulgarians were left outside the new nation's borders, which stoked irredentist sentiments that led to several conflicts with its neighbours and alliances with Germany in both world wars. In 1946 Bulgaria came under the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc and became a one-party socialist state The ruling Communist Party gave up its monopoly on power after the revolutions of 1989 and allowed multiparty elections. Bulgaria then transitioned into a democracy and a market-based economy. Since adopting a democratic constitution in 1991, Bulgaria has been a unitary parliamentary republic composed of 27 provinces, with a high degree of political, administrative, and economic centralisation.

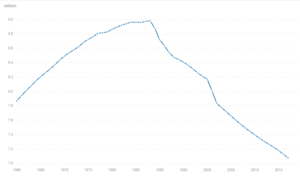

Bulgaria is a member of the European Union, NATO, and the Council of Europe; it is a founding state of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and has taken a seat on the UN Security Council three times. Its market economy is part of the European Single Market and mostly relies on services, followed by industry—especially machine building and mining—and agriculture. Bulgaria is a developing country and ranks 52nd in the Human Development Index, the lowest development rank in the European Union alongside Romania. Widespread corruption is a major socioeconomic issue; Bulgaria ranked as the most corrupt country in the European Union in 2018.[7] The country also faces a demographic crisis, with its population shrinking annually since the late 1980s; it currently numbers roughly seven million, down from a peak of nearly nine million in 1988.

Etymology

The name Bulgaria is derived from the Bulgars, a tribe of Turkic origin that founded the country. Their name is not completely understood and is difficult to trace back earlier than the 4th century AD,[8] but it is possibly derived from the Proto-Turkic word bulģha ("to mix", "shake", "stir") and its derivative bulgak ("revolt", "disorder").[9] The meaning may be further extended to "rebel", "incite" or "produce a state of disorder", and so, in the derivative, the "disturbers".[10][11][12] Ethnic groups in Inner Asia with phonologically similar names were frequently described in similar terms: during the 4th century, the Buluoji, a component of the "Five Barbarian" groups in Ancient China, were portrayed as both a "mixed race" and "troublemakers".[13]

History

Prehistory and antiquity

Neanderthal remains dating to around 150,000 years ago, or the Middle Paleolithic, are some of the earliest traces of human activity in the lands of modern Bulgaria.[14] Remains from Homo sapiens found there are dated ca. 47,000 years BP. This result represents the earliest arrival of modern humans in Europe.[15][16] The Karanovo culture arose circa 6,500 BC and was one of several Neolithic societies in the region that thrived on agriculture.[17] The Copper Age Varna culture (fifth millennium BC) is credited with inventing gold metallurgy.[18][19] The associated Varna Necropolis treasure contains the oldest golden jewellery in the world with an approximate age of over 6,000 years.[20][21] The treasure has been valuable for understanding social hierarchy and stratification in the earliest European societies.[22][23][24]

The Thracians, one of the three primary ancestral groups of modern Bulgarians, appeared on the Balkan Peninsula some time before the 12th century BC.[25][26][27] The Thracians excelled in metallurgy and gave the Greeks the Orphean and Dionysian cults, but remained tribal and stateless.[28] The Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered most of present-day Bulgaria in the 6th century BC and retained control over the region until 479 BC.[29][30] The invasion became a catalyst for Thracian unity, and the bulk of their tribes united under king Teres to form the Odrysian kingdom in the 470s BC.[28][30][31] It was weakened and vassalized by Philip II of Macedon in 341 BC,[32] attacked by Celts in the 3rd century,[33] and finally became a province of the Roman Empire in AD 45.[34]

By the end of the 1st century AD, Roman governance was established over the entire Balkan Peninsula and Christianity began spreading in the region around the 4th century.[28] The Gothic Bible—the first Germanic language book—was created by Gothic bishop Ulfilas in what is today northern Bulgaria around 381.[35] The region came under Byzantine control after the fall of Rome in 476. The Byzantines were engaged in prolonged warfare against Persia and could not defend their Balkan territories from barbarian incursions.[36] This enabled the Slavs to enter the Balkan Peninsula as marauders, primarily through an area between the Danube River and the Balkan Mountains known as Moesia.[37] Gradually, the interior of the peninsula became a country of the South Slavs, who lived under a democracy.[38][39] The Slavs assimilated the partially Hellenized, Romanized, and Gothicized Thracians in the rural areas.[40][41][42][43]

First Bulgarian Empire

Not long after the Slavic incursion, Moesia was once again invaded, this time by the Bulgars under Khan Asparukh.[44] Their horde was a remnant of Old Great Bulgaria, an extinct tribal confederacy situated north of the Black Sea in what is now Ukraine and southern Russia. Asparukh attacked Byzantine territories in Moesia and conquered the Slavic tribes there in 680.[26] A peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire was signed in 681, marking the foundation of the First Bulgarian Empire. The minority Bulgars formed a close-knit ruling caste.[45]

Succeeding rulers strengthened the Bulgarian state throughout the 8th and 9th centuries. Krum introduced a written code of law[46] and checked a major Byzantine incursion at the Battle of Pliska, in which Byzantine emperor Nicephorus I was killed.[47] Boris I abolished paganism in favour of Eastern Orthodox Christianity in 864. The conversion was followed by a Byzantine recognition of the Bulgarian church[48] and the adoption of the Cyrillic alphabet, developed in the capital, Preslav.[49] The common language, religion and script strengthened central authority and gradually fused the Slavs and Bulgars into a unified people speaking a single Slavic language.[50][49] A golden age began during the 34-year rule of Simeon the Great, who oversaw the largest territorial expansion of the state.[51]

After Simeon's death, Bulgaria was weakened by wars with Magyars and Pechenegs and the spread of the Bogomil heresy.[50][52] Preslav was seized by the Byzantine army in 971 after consecutive Rus' and Byzantine invasions.[50] The empire briefly recovered from the attacks under Samuil,[53] but this ended when Byzantine emperor Basil II defeated the Bulgarian army at Klyuch in 1014. Samuil died shortly after the battle,[54] and by 1018 the Byzantines had conquered the First Bulgarian Empire.[55] After the conquest, Basil II prevented revolts by retaining the rule of local nobility, integrating them in Byzantine bureaucracy and aristocracy, and relieving their lands of the obligation to pay taxes in gold, allowing tax in kind instead.[56][57] The Bulgarian Patriarchate was reduced to an archbishopric, but retained its autocephalous status and its dioceses.[57][56]

Second Bulgarian Empire

Byzantine domestic policies changed after Basil's death and a series of unsuccessful rebellions broke out, the largest being led by Peter Delyan. The empire's authority declined after a catastrophic military defeat at Manzikert against Seljuk invaders, and was further disturbed by the Crusades. This prevented Byzantine attempts at Hellenisation and created fertile ground for further revolt. In 1185 Asen dynasty nobles Ivan Asen I and Peter IV organized a major uprising and succeeded in re-establishing the Bulgarian state. Ivan Asen and Peter laid the foundations of the Second Bulgarian Empire with its capital at Tarnovo.[58]

Kaloyan, the third of the Asen monarchs, extended his dominion to Belgrade and Ohrid. He acknowledged the spiritual supremacy of the pope and received a royal crown from a papal legate.[59] The empire reached its zenith under Ivan Asen II (1218–1241), when its borders expanded as far as the coast of Albania, Serbia and Epirus, while commerce and culture flourished.[59][58] Ivan Asen's rule was also marked by a shift away from Rome in religious matters.[60]

The Asen dynasty became extinct in 1257. Internal conflicts and incessant Byzantine and Hungarian attacks followed, enabling the Mongols to establish suzerainty over the weakened Bulgarian state.[59][60] In 1277, swineherd Ivaylo led a great peasant revolt that expelled the Mongols from Bulgaria and briefly made him emperor.[61][58] He was overthrown in 1280 by the feudal landlords,[61] whose factional conflicts caused the Second Bulgarian Empire to disintegrate into small feudal dominions by the 14th century.[58] These fragmented rump states—two tsardoms at Vidin and Tarnovo and the Despotate of Dobrudzha—became easy prey for a new threat arriving from the Southeast: the Ottoman Turks.[59]

Ottoman rule

The Ottomans were employed as mercenaries by the Byzantines in the 1340s but later became invaders in their own right.[62] Sultan Murad I took Adrianople from the Byzantines in 1362; Sofia fell in 1382, followed by Shumen in 1388.[62] The Ottomans completed their conquest of Bulgarian lands in 1393 when Tarnovo was sacked after a three-month siege and the Battle of Nicopolis which brought about the fall of the Vidin Tsardom in 1396. Sozopol was the last Bulgarian settlement to fall, in 1453.[63] The Bulgarian nobility was subsequently eliminated and the peasantry was enserfed to Ottoman masters,[62] while much of the educated clergy fled to other countries.[64]

Christians were considered an inferior class of people under the Ottoman system. Bulgarians were subjected to heavy taxes (including devshirme, or blood tax), their culture was suppressed,[64] and they experienced partial Islamisation.[65] Ottoman authorities established a religious administrative community called the Rum Millet, which governed all Orthodox Christians regardless of their ethnicity.[66] Most of the local population then gradually lost its distinct national consciousness, identifying only by its faith.[67][68] The clergy remaining in some isolated monasteries kept their ethnic identity alive, enabling its survival in remote rural areas,[69] and in the militant Catholic community in the northwest of the country.[70]

As Ottoman power began to wane, Habsburg Austria and Russia saw Bulgarian Christians as potential allies. The Austrians first backed an uprising in Tarnovo in 1598, then a second one in 1686, the Chiprovtsi Uprising in 1688 and finally Karposh's Rebellion in 1689.[71] The Russian Empire also asserted itself as a protector of Christians in Ottoman lands with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774.[71]

The Western European Enlightenment in the 18th century influenced the initiation of a national awakening of Bulgaria.[62] It restored national consciousness and provided an ideological basis for the liberation struggle, resulting in the 1876 April Uprising. Up to 30,000 Bulgarians were killed as Ottoman authorities put down the rebellion. The massacres prompted the Great Powers to take action.[72] They convened the Constantinople Conference in 1876, but their decisions were rejected by the Ottomans. This allowed the Russian Empire to seek a military solution without risking confrontation with other Great Powers, as had happened in the Crimean War.[72] In 1877 Russia declared war on the Ottomans and defeated them with the help of Bulgarian rebels, particularly during the crucial Battle of Shipka Pass which secured Russian control over the main road to Constantinople.[73][74]

Third Bulgarian state

-byTodorBozhinov.png)

The Treaty of San Stefano was signed on 3 March 1878 by Russia and the Ottoman Empire. It was to set up an autonomous Bulgarian principality spanning Moesia, Macedonia and Thrace, roughly on the territories of the Second Bulgarian Empire,[75][76] and this day is now a public holiday called National Liberation Day.[77] The other Great Powers immediately rejected the treaty out of fear that such a large country in the Balkans might threaten their interests. It was superseded by the Treaty of Berlin, signed on 13 July, which provided for a much smaller state only comprising Moesia and the region of Sofia, leaving large populations of ethnic Bulgarians outside the new country.[75][78] This significantly contributed to Bulgaria's militaristic foreign affairs approach during the first half of the 20th century.[79]

The Bulgarian principality won a war against Serbia and incorporated the semi-autonomous Ottoman territory of Eastern Rumelia in 1885, proclaiming itself an independent state on 5 October 1908.[80] In the years following independence, Bulgaria increasingly militarized and was often referred to as "the Balkan Prussia".[81] It became involved in three consecutive conflicts between 1912 and 1918—two Balkan Wars and World War I. After a disastrous defeat in the Second Balkan War, Bulgaria again found itself fighting on the losing side as a result of its alliance with the Central Powers in World War I. Despite fielding more than a quarter of its population in a 1,200,000-strong army[82][83] and achieving several decisive victories at Doiran and Monastir, the country capitulated in 1918. The war resulted in significant territorial losses and a total of 87,500 soldiers killed.[84] More than 253,000 refugees from the lost territories immigrated to Bulgaria from 1912 to 1929,[85] placing additional strain on the already ruined national economy.[86]

The resulting political unrest led to the establishment of a royal authoritarian dictatorship by Tsar Boris III (1918–1943). Bulgaria entered World War II in 1941 as a member of the Axis but declined to participate in Operation Barbarossa and saved its Jewish population from deportation to concentration camps.[87] The sudden death of Boris III in mid-1943 pushed the country into political turmoil as the war turned against Germany, and the communist guerrilla movement gained momentum. The government of Bogdan Filov subsequently failed to achieve peace with the Allies. Bulgaria did not comply with Soviet demands to expel German forces from its territory, resulting in a declaration of war and an invasion by the USSR in September 1944.[88] The communist-dominated Fatherland Front took power, ended participation in the Axis and joined the Allied side until the war ended.[89] Bulgaria suffered little war damage and the Soviet Union demanded no reparations. But all wartime gains, with the notable exception of Southern Dobrudzha, were lost.[90]

The left-wing coup d'état of 9 September 1944 led to the abolition of the monarchy and the executions of some 1,000–3,000 dissidents, war criminals, and members of the former royal elite.[91][92][93] But it was not until 1946 that a one-party people's republic was instituted following a referendum.[94] It fell into the Soviet sphere of influence under the leadership of Georgi Dimitrov (1946–1949), who established a repressive, rapidly industrializing Stalinist state.[90] By the mid-1950s standards of living rose significantly and political repressions eased.[95][96] The Soviet-style planned economy saw some market-oriented policies emerging on an experimental level under Todor Zhivkov (1954–1989).[97] Compared to wartime levels, national GDP increased five-fold and per capita GDP quadrupled by the 1980s,[98] although severe debt spikes took place in 1960, 1977 and 1980.[99] Zhivkov's daughter Lyudmila bolstered national pride by promoting Bulgarian heritage, culture and arts worldwide.[100] Facing declining birth rates among the ethnic Bulgarian majority, in 1984 Zhivkov's government forced the minority ethnic Turks to adopt Slavic names in an attempt to erase their identity and assimilate them.[101] These policies resulted in the emigration of some 300,000 ethnic Turks to Turkey.[102][103]

The Communist Party was forced to give up its political monopoly on 10 November 1989 under the influence of the Revolutions of 1989. Zhivkov resigned and Bulgaria embarked on a transition to a parliamentary democracy.[104] The first free elections in June 1990 were won by the Communist Party, now rebranded as the Bulgarian Socialist Party.[105] A new constitution that provided for a relatively weak elected president and for a prime minister accountable to the legislature was adopted in July 1991.[106] The new system initially failed to improve living standards or create economic growth—the average quality of life and economic performance remained lower than under communism well into the early 2000s.[107] After 2001 economic, political and geopolitical conditions improved greatly,[108] and Bulgaria achieved high Human Development status in 2003.[109] It became a member of NATO in 2004[110] and participated in the War in Afghanistan. After several years of reforms it joined the European Union and single market in 2007 despite Brussels' concerns about government corruption.[111] Bulgaria hosted the 2018 Presidency of the Council of the European Union at the National Palace of Culture in Sofia.[112]

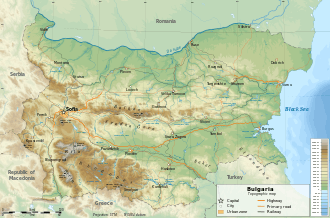

Geography

Bulgaria occupies a portion of the eastern Balkan peninsula, bordering five countries—Greece and Turkey to the south, North Macedonia and Serbia to the west, and Romania to the north. The land borders have a total length of 1,808 kilometres (1,123 mi), and the coastline has a length of 354 kilometres (220 mi).[113] Its total area of 110,994 square kilometres (42,855 sq mi) ranks it as the world's 105th-largest country.[1][114] Bulgaria's geographic coordinates are 43° N 25° E.[115] The most notable topographical features are the Danubian Plain, the Balkan Mountains, the Thracian Plain, and the Rila-Rhodope massif.[113] The southern edge of the Danubian Plain slopes upward into the foothills of the Balkans, while the Danube defines the border with Romania. The Thracian Plain is roughly triangular, beginning southeast of Sofia and broadening as it reaches the Black Sea coast.[113]

The Balkan mountains run laterally through the middle of the country from west to east. The mountainous southwest has two distinct alpine type ranges - Rila and Pirin, which border the lower but more extensive Rhodope Mountains to the east, and various medium altitude mountains to west, northwest and south, like Vitosha, Osogovo and Belasitsa.[113] Musala, at 2,925 metres (9,596 ft), is the highest point in both Bulgaria and the Balkan peninsula. The Black Sea coast is the country's lowest point.[115] Plains occupy about one third of the territory, while plateaux and hills occupy 41%.[116] Most rivers are short and with low water levels. The longest river located solely in Bulgarian territory, the Iskar, has a length of 368 kilometres (229 mi). The Struma and the Maritsa are two major rivers in the south.[117][113]

Bulgaria has a varied and changeable climate, which results from being positioned at the meeting point of the Mediterranean, Oceanic and Continental air masses combined with the barrier effect of its mountains.[113] Northern Bulgaria averages 1 °C (1.8 °F) cooler, and registers 200 millimetres (7.9 in) more precipitation, than the regions south of the Balkan mountains. Temperature amplitudes vary significantly in different areas. The lowest recorded temperature is −38.3 °C (−36.9 °F), while the highest is 45.2 °C (113.4 °F).[118] Precipitation averages about 630 millimetres (24.8 in) per year, and varies from 500 millimetres (19.7 in) in Dobrudja to more than 2,500 millimetres (98.4 in) in the mountains. Continental air masses bring significant amounts of snowfall during winter.[119]

Biodiversity and environment

The interaction of climatic, hydrological, geological and topographical conditions has produced a relatively wide variety of plant and animal species.[120] Bulgaria's biodiversity, one of the richest in Europe,[121] is conserved in three national parks, 11 nature parks, 10 biosphere reserves and 565 protected areas.[122][123][124] Ninety-three of the 233 mammal species of Europe are found in Bulgaria, along with 49% of butterfly and 30% of vascular plant species.[125] Overall, 41,493 plant and animal species are present.[125] Larger mammals with sizable populations include deer (106,323 individuals), wild boars (88,948), jackals (47,293) and foxes (32,326). Partridges number some 328,000 individuals, making them the most widespread gamebird.[126] A third of all nesting birds in Bulgaria can be found in Rila National Park, which also hosts Arctic and alpine species at high altitudes.[127] Flora includes more than 3,800 vascular plant species of which 170 are endemic and 150 are considered endangered.[120] A checklist of larger fungi in Bulgaria by the Institute of Botany identifies more than 1,500 species.[128] More than 35% of the land area is covered by forests.[129]

In 1998, the Bulgarian government adopted the National Biological Diversity Conservation Strategy, a comprehensive programme seeking the preservation of local ecosystems, protection of endangered species and conservation of genetic resources.[130] Bulgaria has some of the largest Natura 2000 areas in Europe covering 33.8% of its territory.[131] It also achieved its Kyoto Protocol objective of reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 30% from 1990 to 2009.[132]

Bulgaria ranks 30th in the 2018 Environmental Performance Index, but scores low on air quality.[133] Particulate levels are the highest in Europe,[134] especially in urban areas affected by automobile traffic and coal-based power stations.[135][136] One of these, the lignite-fired Maritsa Iztok-2 station, is causing the highest damage to health and the environment in the European Union.[137] Pesticide use in agriculture and antiquated industrial sewage systems produce extensive soil and water pollution.[138] Water quality began to improve in 1998 and has maintained a trend of moderate improvement. Over 75% of surface rivers meet European standards for good quality.[139]

Politics

Bulgaria is a parliamentary democracy where the prime minister is the head of government and the most powerful executive position.[108] The political system has three branches—legislative, executive and judicial, with universal suffrage for citizens at least 18 years old. The Constitution also provides possibilities of direct democracy, namely petitions and national referenda. Elections are supervised by an independent Central Election Commission that includes members from all major political parties. Parties must register with the commission prior to participating in a national election.[141] Normally, the prime minister-elect is the leader of the party receiving the most votes in parliamentary elections, although this is not always the case.[108]

Unlike the prime minister, presidential domestic power is more limited. The directly elected president serves as head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and has the authority to return a bill for further debate, although the parliament can override the presidential veto by a simple majority vote.[108] Political parties gather in the National Assembly, a body of 240 deputies elected to four-year terms by direct popular vote. The National Assembly has the power to enact laws, approve the budget, schedule presidential elections, select and dismiss the prime minister and other ministers, declare war, deploy troops abroad, and ratify international treaties and agreements.[142]

Overall, Bulgaria displays a pattern of unstable governments.[143] Boyko Borisov is serving his third term as prime minister since 2009,[144] when his centre-right, pro-EU party GERB won the general election and ruled as a minority government with 117 seats in the National Assembly.[145] His first government resigned on 20 February 2013 after nationwide protests caused by high costs of utilities, low living standards, corruption[146] and the perceived failure of the democratic system. The protest wave was notable for self-immolations, spontaneous demonstrations and a strong sentiment against political parties.[147]

The subsequent snap elections in May resulted in a narrow win for GERB,[148] but the Bulgarian Socialist Party eventually formed a government led by Plamen Oresharski after Borisov failed to secure parliamentary support.[149][150] The Oresharski government resigned in July 2014 amid continuing large-scale protests.[151][152][153] A caretaker government took over[154] and called the October 2014 elections[155] which resulted in a third GERB victory, but a total of eight parties entered parliament.[156] Borisov formed a coalition[157] with several right-wing parties, but resigned again after the candidate backed by his party failed to win the 2016 Presidential election. The March 2017 snap election was again won by GERB, but with 95 seats in Parliament. They formed a coalition with the far-right United Patriots, who hold 27 seats.[144]

Freedom House has reported a continuing deterioration of democratic governance after 2009, citing reduced media independence, stalled reforms, abuse of authority at the highest level and increased dependence of local administrations on the central government.[158] Bulgaria is still listed as "Free", with a political system designated as a semi-consolidated democracy, albeit with deteriorating scores.[158] The Democracy Index defines it as a "Flawed democracy".[159] A 2018 survey by the Institute for Economics and Peace reported that less than 15% of respondents considered elections to be fair.[160]

Legal system

Bulgaria has a civil law legal system.[161] The judiciary is overseen by the Ministry of Justice. The Supreme Administrative Court and the Supreme Court of Cassation are the highest courts of appeal and oversee the application of laws in subordinate courts.[141] The Supreme Judicial Council manages the system and appoints judges. The legal system is regarded by both domestic and international observers as one of Europe's most inefficient due to pervasive lack of transparency and corruption.[162][163][164][165][166] Law enforcement is carried out by organisations mainly subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior.[167] The General Directorate of National Police (GDNP) combats general crime and maintains public order.[168] GDNP fields 26,578 police officers in its local and national sections.[169] The bulk of criminal cases are transport-related, followed by theft and drug-related crime; homicide rates are low.[170] The Ministry of the Interior also heads the Border Police Service and the National Gendarmerie—a specialized branch for anti-terrorist activity, crisis management and riot control. Counterintelligence and national security are the responsibility of the State Agency for National Security.[171]

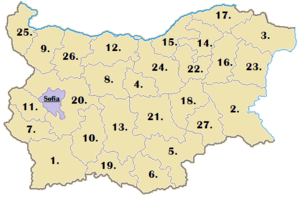

Administrative divisions

Bulgaria is a unitary state.[172] Since the 1880s, the number of territorial management units has varied from seven to 26.[173] Between 1987 and 1999 the administrative structure consisted of nine provinces (oblasti, singular oblast). A new administrative structure was adopted in parallel with the decentralization of the economic system.[174] It includes 27 provinces and a metropolitan capital province (Sofia-Grad). All areas take their names from their respective capital cities. The provinces are subdivided into 265 municipalities. Municipalities are run by mayors, who are elected to four-year terms, and by directly elected municipal councils. Bulgaria is a highly centralized state where the Council of Ministers directly appoints regional governors and all provinces and municipalities are heavily dependent on it for funding.[141]

|

Largest cities and towns

Foreign relations and security

Bulgaria became a member of the United Nations in 1955 and since 1966 has been a non-permanent member of the Security Council three times, most recently from 2002 to 2003.[176] It was also among the founding nations of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in 1975. Euro-Atlantic integration has been a priority since the fall of communism, although the communist leadership also had aspirations of leaving the Warsaw Pact and joining the European Communities by 1987.[177][178] Bulgaria signed the European Union Treaty of Accession on 25 April 2005,[179] and became a full member of the European Union on 1 January 2007.[111] In addition, it has a tripartite economic and diplomatic collaboration with Romania and Greece,[180] good ties with China[181] and Vietnam[182] and a historical relationship with Russia.[183][184][185][186]

Bulgaria deployed significant numbers of both civilian and military advisors in Soviet-allied countries like Nicaragua[187] and Libya during the Cold War.[188] The first deployment of foreign troops on Bulgarian soil since World War II occurred in 2001, when the country hosted six KC-135 Stratotanker aircraft and 200 support personnel for the war effort in Afghanistan.[23] International military relations were further expanded with accession to NATO in March 2004[110] and the US-Bulgarian Defence Cooperation Agreement signed in April 2006. Bezmer and Graf Ignatievo air bases, the Novo Selo training range, and a logistics centre in Aytos subsequently became joint military training facilities cooperatively used by the United States and Bulgarian militaries.[189][190] Despite its active international defence collaborations, Bulgaria ranks as among the most peaceful countries globally, tying 6th alongside Iceland regarding domestic and international conflicts, and 26th on average in the Global Peace Index.[160]

Domestic defence is the responsibility of the all-volunteer Bulgarian armed forces, composed of land forces, navy and an air force. The land forces consist of two mechanized brigades and eight independent regiments and battalions; the air force operates 106 aircraft and air defence systems in six air bases, and the navy operates various ships, helicopters and coastal defence weapons.[191] Active troops dwindled from 152,000 in 1988[192] to 31,300 in 2017, supplemented by 3,000 reservists and 16,000 paramilitary.[193] Inventory is mostly made up of Soviet equipment like Mikoyan MiG-29 and Sukhoi Su-25 jets,[194] S-300PT air defence systems[195] and SS-21 Scarab short-range ballistic missiles.[196]

Economy

Bulgaria has an open, upper middle income range market economy where the private sector accounts for more than 70% of GDP.[197][198] From a largely agricultural country with a predominantly rural population in 1948, by the 1980s Bulgaria had transformed into an industrial economy with scientific and technological research at the top of its budgetary expenditure priorities.[199] The loss of COMECON markets in 1990 and the subsequent "shock therapy" of the planned system caused a steep decline in industrial and agricultural production, ultimately followed by an economic collapse in 1997.[200][201] The economy largely recovered during a period of rapid growth several years later,[200] but the average salary of 1,036 leva ($615) per month remains the lowest in the EU.[202] More than a fifth of the labour force are employed on a minimum wage of $1.16 per hour.[203]

A balanced budget was achieved in 2003 and the country began running a surplus the following year.[204] Expenditures amounted to $21.15 billion and revenues were $21.67 billion in 2017.[205] Most government spending on institutions is earmarked for security. The ministries of defence, the interior and justice are allocated the largest share of the annual government budget, whereas those responsible for the environment, tourism and energy receive the least amount of funding.[206] Taxes form the bulk of government revenue[206] at 30% of GDP.[207] Bulgaria has some of the lowest corporate income tax rates in the EU at a flat 10% rate.[208] The tax system is two-tier. Value added tax, excise duties, corporate and personal income tax are national, whereas real estate, inheritance, and vehicle taxes are levied by local authorities.[209] Strong economic performance in the early 2000s reduced government debt from 79.6% in 1998 to 14.1% in 2008.[204] It has since increased to 28.7% of GDP by 2016, but remains the third lowest in the EU.[210]

The Yugozapaden planning area is the most developed region with a per capita gross domestic product (PPP) of $26,580 in 2016.[211] It includes the capital city and the surrounding Sofia Province, which alone generate 42% of national gross domestic product despite hosting only 22% of the population.[212][213] GDP per capita (in PPS) and the cost of living in 2019 stood at 53 and 52.8% of the EU average (100%), respectively.[214][215] National PPP GDP was estimated at $143.1 billion in 2016, with a per capita value of $20,116.[216] Economic growth statistics take into account illegal transactions from the informal economy, which is the largest in the EU as a percentage of economic output.[217][218] The Bulgarian National Bank issues the national currency, lev, which is pegged to the euro at a rate of 1.95583 levа per euro.[219]

After several consecutive years of high growth, repercussions of the financial crisis of 2007–2008 resulted in a 3.6% contraction of GDP in 2009 and increased unemployment.[220][221] Industrial output declined 10%, mining by 31%, and ferrous and metal production marked a 60% drop.[222] Positive growth was restored in 2010 but intercompany debt exceeded $59 billion, meaning that 60% of all Bulgarian companies were mutually indebted.[223] By 2012, it had increased to $97 billion, or 227% of GDP.[224] The government implemented strict austerity measures with IMF and EU encouragement to some positive fiscal results, but the social consequences of these measures, such as increased income inequality and accelerated outward migration, have been "catastrophic" according to the International Trade Union Confederation.[225]

Siphoning of public funds to the families and relatives of politicians from incumbent parties has resulted in fiscal and welfare losses to society.[226][227] Bulgaria ranks 71st in the Corruption Perceptions Index[228] and experiences the worst levels of corruption in the European Union, a phenomenon that remains a source of profound public discontent.[229][230] Along with organized crime, corruption has resulted in a rejection of the country's Schengen Area application and withdrawal of foreign investment.[231][232][233] Government officials reportedly engage in embezzlement, influence trading, government procurement violations and bribery with impunity.[162] Government procurement in particular is a critical area in corruption risk. An estimated 10 billion leva ($5.99 billion) of state budget and European cohesion funds are spent on public tenders each year;[234] nearly 14 billion ($8.38 billion) were spent on public contracts in 2017 alone.[235] A large share of these contracts are awarded to a few politically connected[236] companies amid widespread irregularities, procedure violations and tailor-made award criteria.[237] Despite repeated criticism from the European Commission,[233] EU institutions refrain from taking measures against Bulgaria because it supports Brussels on a number of issues, unlike Poland or Hungary.[229]

Structure and sectors

The labour force is 3.36 million people,[238] of whom 6.8% are employed in agriculture, 26.6% in industry and 66.6% in the services sector.[239] Extraction of metals and minerals, production of chemicals, machine building, steel, biotechnology, tobacco and food processing and petroleum refining are among the major industrial activities.[240][241][242] Mining alone employs 24,000 people and generates about 5% of the country's GDP; the number of employed in all mining-related industries is 120,000.[243][244] Bulgaria is Europe's fifth-largest coal producer.[244][245] Local deposits of coal, iron, copper and lead are vital for the manufacturing and energy sectors.[246] The main destinations of Bulgarian exports outside the EU are Turkey, China and the United States, while Russia and Turkey are by far the largest import partners. Most of the exports are manufactured goods, machinery, chemicals, fuel products and food.[247] Two-thirds of food and agricultural exports go to OECD countries.[248]

Although cereal and vegetable output dropped by 40% between 1990 and 2008,[249] output in grains has since increased, and the 2016–2017 season registered the biggest grain output in a decade.[250][251] Maize, barley, oats and rice are also grown. Quality Oriental tobacco is a significant industrial crop.[252] Bulgaria is also the largest producer globally of lavender and rose oil, both widely used in fragrances.[23][253][254][255] Within the services sector, tourism is a significant contributor to economic growth. Sofia, Plovdiv, Veliko Tarnovo, coastal resorts Albena, Golden Sands and Sunny Beach and winter resorts Bansko, Pamporovo and Borovets are some of the locations most visited by tourists.[256][257] Most visitors are Romanian, Turkish, Greek and German.[258] Tourism is additionally encouraged through the 100 Tourist Sites system.[259]

Science and technology

Spending on research and development amounts to 0.78% of GDP,[260] and the bulk of public R&D funding goes to the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (BAS).[261] Private businesses accounted for more than 73% of R&D expenditures and employed 42% of Bulgaria's 22,000 researchers in 2015.[262] The same year, Bulgaria ranked 39th out of 50 countries in the Bloomberg Innovation Index, the highest score being in education (24th) and the lowest in value-added manufacturing (48th).[263] Chronic government underinvestment in research since 1990 has forced many professionals in science and engineering to leave Bulgaria.[264]

.jpg)

Despite the lack of funding, research in chemistry, materials science and physics remains strong.[261] Antarctic research is actively carried out through the St. Kliment Ohridski Base on Livingston Island in Western Antarctica.[265][266] The information and communication technologies (ICT) sector generates three per cent of economic output and employs 40,000[267] to 51,000 software engineers.[268] Bulgaria was known as a "Communist Silicon Valley" during the Soviet era due to its key role in COMECON computing technology production.[269] The country is a regional leader in high performance computing: it operates Avitohol, the most powerful supercomputer in Southeast Europe, and will host one of the eight petascale EuroHPC supercomputers.[270][271]

Bulgaria has made numerous contributions to space exploration.[272] These include two scientific satellites, more than 200 payloads and 300 experiments in Earth orbit, as well as two cosmonauts since 1971.[272] Bulgaria was the first country to grow wheat and vegetables in space with its Svet greenhouses on the Mir space station.[273][274] It was involved in the development of the Granat gamma-ray observatory[275] and the Vega program, particularly in modelling trajectories and guidance algorithms for both Vega probes.[276][277] Bulgarian instruments have been used in the exploration of Mars, including a spectrometer that took the first high quality spectroscopic images of Martian moon Phobos with the Phobos 2 probe.[272][275] Cosmic radiation en route to and around the planet has been mapped by Liulin-ML dosimeters on the ExoMars TGO.[278] Variants of these instruments have also been fitted on the International Space Station and the Chandrayaan-1 lunar probe.[279][280] Another lunar mission, SpaceIL's Beresheet, was also equipped with a Bulgarian-manufactured imaging payload.[281] Bulgaria's first geostationary communications satellite—BulgariaSat-1—was launched by SpaceX in 2017.[282]

Infrastructure

Telephone services are widely available, and a central digital trunk line connects most regions.[283] Vivacom (BTC) serves more than 90% of fixed lines and is one of the three operators providing mobile services, along with A1 and Telenor.[284][285] Internet penetration stood at 66.8% of the population aged 16–74 and 75.1% of households, in 2019.[286][287]

Bulgaria's strategic geographic location and well-developed energy sector make it a key European energy centre despite its lack of significant fossil fuel deposits.[288] Thermal power plants generate 48.9% of electricity, followed by nuclear power from the Kozloduy reactors (34.8%) and renewable sources (16.3%).[289] Equipment for a second nuclear power station at Belene has been acquired, but the fate of the project remains uncertain.[290] Installed capacity amounts to 12,668 MW, allowing Bulgaria to exceed domestic demand and export energy.[291]

The national road network has a total length of 19,512 kilometres (12,124 mi),[292] of which 19,235 kilometres (11,952 mi) are paved. Railroads are a major mode of freight transportation, although highways carry a progressively larger share of freight. Bulgaria has 6,238 kilometres (3,876 mi) of railway track[283] and currently a total of 81 kilometres (50 miles) of high-speed lines are in operation.[293][294] Rail links are available with Romania, Turkey, Greece, and Serbia, and express trains serve direct routes to Kiev, Minsk, Moscow and Saint Petersburg.[295] Sofia and Plovdiv are the country's air travel hubs, while Varna and Burgas are the principal maritime trade ports.[283]

Demographics

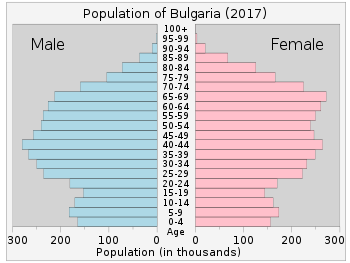

The population of Bulgaria is 7,364,570 people according to the 2011 national census. The majority of the population, 72.5%, reside in urban areas.[296] As of 2019, Sofia is the most populated urban centre with 1,241,675 people, followed by Plovdiv (346,893), Varna (336,505), Burgas (202,434) and Ruse (142,902).[213] Bulgarians are the main ethnic group and constitute 84.8% of the population. Turkish and Roma minorities account for 8.8 and 4.9%, respectively; some 40 smaller minorities account for 0.7%, and 0.8% do not self-identify with an ethnic group.[297][298] Former Statistics head Reneta Indzhova has disputed the 2011 census figures, suggesting the actual population is smaller than reported.[299][300] The Roma minority is usually underestimated in census data and may represent up to 11% of the population.[301][302] Population density is 65 per square kilometre, almost half the European Union average.[303]

In 2018 the average total fertility rate (TFR) across Bulgaria was 1.56 children per woman,[304] below the replacement rate of 2.1, it remains considerably below the high of 5.83 children per woman in 1905.[305] Bulgaria subsequently has one of the oldest populations in the world, with the average age of 43 years.[306]

Bulgaria is in a state of demographic crisis.[307][308] It has had negative population growth since the early 1990s, when the economic collapse caused a long-lasting emigration wave.[309] Some 937,000 to 1,200,000 people—mostly young adults—left the country by 2005.[309][310] The majority of children are born to unmarried women.[311] Furthermore, a third of all households consist of only one person and 75.5% of families do not have children under the age of 16.[308] The resulting birth rates are among the lowest in the world[312][313] while death rates are among the highest.[314]

High death rates result from a combination of an ageing population, a high number of people at risk of poverty and a weak healthcare system.[315] More than 80% of all deaths are due to cancer and cardiovascular conditions; nearly a fifth of those are avoidable.[316] Mortality rates can be sharply reduced to levels below the EU average through timely and adequate access to medical services, which the healthcare system does not provide fully.[317] Although healthcare in Bulgaria is nominally universal,[318] out-of-pocket expenses account for nearly half of all healthcare spending, which significantly limits access to medical care.[319] Other problems disrupting care provision are the emigration of doctors due to low wages, understaffed and under-equipped regional hospitals, supply shortages and frequent changes to the basic service package for those insured.[320][321] The 2018 Bloomberg Health Care Efficiency Index ranked Bulgaria last out of 56 countries.[322] Average life expectancy is 74.8 years compared with an EU average of 80.99 and a world average of 72.38.[323][324]

.jpg)

Public expenditures for education are far below the European Union average as well.[325] Educational standards were once high,[326] but have declined significantly since the early 2000s.[325] Bulgarian students were among the highest-scoring in the world in terms of reading in 2001, performing better than their Canadian and German counterparts; by 2006, scores in reading, math and science had dropped. By 2018, Programme for International Student Assessment studies found 47% of pupils in the 9th grade to be functionally illiterate in reading and natural sciences.[327] Average basic literacy stands high at 98.4% with no significant difference between sexes.[328] The Ministry of Education and Science partially funds public schools, colleges and universities, sets criteria for textbooks and oversees the publishing process. Education in primary and secondary public schools is free and compulsory.[326] The process spans through 12 grades, where grades one through eight are primary and nine through twelve are secondary level. Higher education consists of a 4-year bachelor degree and a 1-year master's degree.[329] Bulgaria's highest-ranked higher education institution is Sofia University.[330][331]

Bulgarian is the only language with official status and native for 85% of the population.[332] It belongs to the Slavic group of languages, but it has a number of grammatical peculiarities, shared with its closest relative Macedonian, that set it apart from other Slavic languages: these include a complex verbal morphology (which also codes for distinctions in evidentiality), the absence of noun cases and infinitives, and the use of a suffixed definite article.[333] Other major languages are Turkish and Romani, which according to the 2011 census were spoken natively by 9.1% and 4.2% respectively.

The country scores high in gender equality, ranking 18th in the 2018 Global Gender Gap Report.[334] Although women's suffrage was enabled relatively late, in 1937, women today have equal political rights, high workforce participation and legally mandated equal pay.[334] Bulgaria has the highest ratio of female ICT researchers in the EU,[335] as well as the second-highest ratio of females in the technology sector at 44.6% of the workforce. High levels of female participation are a legacy of the Socialist era.[336]

Religion

More than three-quarters of Bulgarians subscribe to Eastern Orthodoxy.[337] Sunni Muslims are the second-largest religious community and constitute 10% of Bulgaria's overall religious makeup, although a majority of them are not observant and find the use of Islamic veils in schools unacceptable.[338] Less than 3% of the population are affiliated with other religions and 11.8% are irreligious or do not self-identify with a religion.[337] The Bulgarian Orthodox Church gained autocephalous status in AD 927,[339][340] and has 12 dioceses and over 2,000 priests.[341] Bulgaria is a secular state with guaranteed religious freedom by constitution, but Orthodoxy is designated as a "traditional" religion.[342]

Culture

Contemporary Bulgarian culture blends the formal culture that helped forge a national consciousness towards the end of Ottoman rule with millennia-old folk traditions.[343] An essential element of Bulgarian folklore is fire, used to banish evil spirits and illnesses. Many of these are personified as witches, whereas other creatures like zmey and samodiva (veela) are either benevolent guardians or ambivalent tricksters.[344] Some rituals against evil spirits have survived and are still practised, most notably kukeri and survakari.[345] Martenitsa is also widely celebrated.[346] Nestinarstvo, a ritual fire-dance of Thracian origin, is included in the list of UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.[347][348]

Nine historical and natural objects are UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Pirin National Park, Sreburna Nature Reserve, the Madara Rider, the Thracian tombs in Sveshtari and Kazanlak, the Rila Monastery, the Boyana Church, the Rock-hewn Churches of Ivanovo and the ancient city of Nesebar.[349] The Rila Monastery was established by Saint John of Rila, Bulgaria's patron saint, whose life has been the subject of numerous literary accounts since Medieval times.[350]

The establishment of the Preslav and Ohrid literary schools in the 10th century is associated with a golden period in Bulgarian literature during the Middle Ages.[350] The schools' emphasis on Christian scriptures made the Bulgarian Empire a centre of Slavic culture, bringing Slavs under the influence of Christianity and providing them with a written language.[351][352][353] Its alphabet, Cyrillic script, was developed by the Preslav Literary School.[354] The Tarnovo Literary School, on the other hand, is associated with a Silver age of literature defined by high-quality manuscripts on historical or mystical themes under the Asen and Shishman dynasties.[350] Many literary and artistic masterpieces were destroyed by the Ottoman conquerors, and artistic activities did not re-emerge until the National Revival in the 19th century.[343] The enormous body of work of Ivan Vazov (1850–1921) covered every genre and touched upon every facet of Bulgarian society, bridging pre-Liberation works with literature of the newly established state.[350] Notable later works are Bay Ganyo by Aleko Konstantinov, the Nietzschean poetry of Pencho Slaveykov, the Symbolist poetry of Peyo Yavorov and Dimcho Debelyanov, the Marxist-inspired works of Geo Milev and Nikola Vaptsarov, and the Socialist realism novels of Dimitar Dimov and Dimitar Talev.[350] Tzvetan Todorov is a notable contemporary author,[355] while Bulgarian-born Elias Canetti was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1981.[356]

.jpg)

А religious visual arts heritage includes frescoes, murals and icons, many produced by the medieval Tarnovo Artistic School.[357] Like literature, it was not until the National Revival when Bulgarian visual arts began to reemerge. Zahari Zograf was a pioneer of the visual arts in the pre-Liberation era.[343] After the Liberation, Ivan Mrkvička, Anton Mitov, Vladimir Dimitrov, Tsanko Lavrenov and Zlatyu Boyadzhiev introduced newer styles and substance, depicting scenery from Bulgarian villages, old towns and historical subjects. Christo is the most famous Bulgarian artist of the 21st century, known for his outdoor installations.[343]

Folk music is by far the most extensive traditional art and has slowly developed throughout the ages as a fusion of Far Eastern, Oriental, medieval Eastern Orthodox and standard Western European tonalities and modes.[358] Bulgarian folk music has a distinctive sound and uses a wide range of traditional instruments, such as gadulka, gaida, kaval and tupan. A distinguishing feature is extended rhythmical time, which has no equivalent in the rest of European music.[23] The State Television Female Vocal Choir won a Grammy Award in 1990 for its performances of Bulgarian folk music.[359] Written musical composition can be traced back to the works of Yoan Kukuzel (c. 1280–1360),[360] but modern classical music began with Emanuil Manolov, who composed the first Bulgarian opera in 1890.[343] Pancho Vladigerov and Petko Staynov further enriched symphony, ballet and opera, which singers Ghena Dimitrova, Boris Christoff, Ljuba Welitsch and Nicolai Ghiaurov elevated to a world-class level.[343][361][362][363][364][365][366] Bulgarian performers have gained acclaim in other genres like electropop (Mira Aroyo), jazz (Milcho Leviev) and blends of jazz and folk (Ivo Papazov).[343]

The Bulgarian National Radio, bTV and daily newspapers Trud, Dnevnik and 24 Chasa are some of the largest national media outlets.[367] Bulgarian media were described as generally unbiased in their reporting in the early 2000s and print media had no legal restrictions.[368] Since then, freedom of the press has deteriorated to the point where Bulgaria scores 111th globally in the World Press Freedom Index, lower than all European Union members and membership candidate states. The government has diverted EU funds to sympathetic media outlets and bribed others to be less critical on problematic topics, while attacks against individual journalists have increased.[369][370] Collusion between politicians, oligarchs and the media is widespread.[369]

Bulgarian cuisine is similar to that of other Balkan countries and demonstrates strong Turkish and Greek influences.[371] Yogurt, lukanka, banitsa, shopska salad, lyutenitsa and kozunak are among the best-known local foods. Meat consumption is lower than the European average, given a cultural preference for a large variety of salads.[371] Bulgaria was the world's second-largest wine exporter until 1989, but has since lost that position.[372][373] The 2016 harvest yielded 128 million litres of wine, of which 62 million was exported mainly to Romania, Poland and Russia.[374] Mavrud, Rubin, Shiroka melnishka, Dimiat and Cherven Misket are the typical grapes used in Bulgarian wine.[375] Rakia is a traditional fruit brandy that was consumed in Bulgaria as early as the 14th century.[376]

Sports

.jpg)

Bulgaria appeared at the first modern Olympic games in 1896, when it was represented by gymnast Charles Champaud.[377] Since then, Bulgarian athletes have won 52 gold, 89 silver, and 83 bronze medals,[378] ranking 25th in the all-time medal table. Weight-lifting is a signature sport of Bulgaria. Coach Ivan Abadzhiev developed innovative training practices that have produced many Bulgarian world and Olympic champions in weight-lifting since the 1980s.[379] Bulgarian athletes have also excelled in wrestling, boxing, gymnastics, volleyball and tennis.[379] Stefka Kostadinova is the reigning world record holder in the women's high jump at 2.09 metres (6 feet 10 inches), achieved during the 1987 World Championships.[380] Grigor Dimitrov is the first Bulgarian tennis player in the Top 3 ATP Rankings.[381]

Football is the most popular sport in the country by a substantial margin. The national football team's best performance was a semi-final at the 1994 FIFA World Cup, when the squad was spearheaded by forward Hristo Stoichkov.[379] Stoichkov is the most successful Bulgarian player of all time; he was awarded the Golden Boot and the Golden Ball and was considered one of the best in the world while playing for FC Barcelona in the 1990s.[382][383] CSKA and Levski, both based in Sofia,[379] are the most successful clubs domestically and long-standing rivals.[384] Ludogorets is remarkable for having advanced from the local fourth division to the 2014–15 UEFA Champions League group stage in a mere nine years.[385] Placed 39th in 2018, it is Bulgaria's highest-ranked club in UEFA.[386]

Footnotes

- The official number of Romani citizens may be lower than the actual number. See Demographics.

References

- Penin, Rumen (2007). Природна география на България [Natural Geography of Bulgaria] (in Bulgarian). Bulvest 2000. p. 18. ISBN 978-954-18-0546-6.

- "Field listing: Area". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "Population and Demographic Processes in 2019 | National statistical institute". www.nsi.bg. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Corruption Perceptions Index 2018 Executive Summary p. 12" (PDF). transparency.org. Transparency International. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Golden 1992, pp. 103–104.

- Bowersock, Glen W. (1999). Late Antiquity: a Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. p. 354. ISBN 978-0674511736.

- Chen 2012, p. 97.

- Petersen, Leif Inge Ree (2013). Siege Warfare and Military Organization in the Successor States (400–800 AD): Byzantium, the West and Islam. Brill. p. 369. ISBN 978-9004254466.

- Golden 1992, p. 104.

- Chen 2012, pp. 92–95, 97.

- Tillier, Anne-Marie; Sirakov, Nikolay; Guadelli, Aleta; Fernandez, Philippe; Sirakova, Svoboda (October 2017). "Evidence of Neanderthals in the Balkans: The infant radius from Kozarnika Cave (Bulgaria)". Journal of Human Evolution. 111 (111): 54–62. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.06.002. PMID 28874274.

- Fewlass, H., Talamo, S., Wacker, L. et al. A 14C chronology for the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition at Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria. Nat Ecol Evol (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1136-3.

- Hublin, J., Sirakov, N., Aldeias, V. et al. Initial Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens from Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria. Nature (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2259-z.

- Gimbutas, Marija A. (1974). The Gods and Goddesses of Old Europe: 7000 to 3500 BC Myths, Legends and Cult Images. University of California Press. pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-0520019959.

- Roberts, Benjamin W.; Thornton, Christopher P. (2009). "Development of metallurgy in Eurasia". Antiquity. Department of Prehistory and Europe, British Museum. 83 (322): 1015. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00099312. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

In contrast, the earliest exploitation and working of gold occurs in the Balkans during the mid-fifth millennium BC, several centuries after the earliest known copper smelting. This is demonstrated most spectacularly in the various objects adorning the burials at Varna, Bulgaria (Renfrew 1986; Highamet al. 2007). In contrast, the earliest gold objects found in Southwest Asia date only to the beginning of the fourth millennium BC as at Nahal Qanah in Israel (Golden 2009), suggesting that gold exploitation may have been a Southeast European invention, albeit a short-lived one.

- de Laet, Sigfried J. (1996). History of Humanity: From the Third Millennium to the Seventh Century BC. UNESCO / Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-92-3-102811-3.

The first major gold-working centre was situated at the mouth of the Danube, on the shores of the Black Sea in Bulgaria

- Grande, Lance (2009). Gems and Gemstones: Timeless Natural Beauty of the Mineral World. University of Chicago Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-226-30511-0.

The oldest known gold jewelry in the world is from an archaeological site in Varna Necropolis, Bulgaria, and is over 6,000 years old (radiocarbon dated between 4,600 BC and 4,200 BC).

- Anthony, David W.; Chi, Jennifer, eds. (2010). The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley, 5000–3500 BC. Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 39, 201. ISBN 978-0-691-14388-0.

grave 43 at the Varna cemetery, the richest single grave from Old Europe, dated about 4600–4500 BC.

- "The Gumelnita Culture". Government of France. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

The Necropolis at Varna is an important site in understanding this culture.

- "Bulgaria Factbook". United States Central Command. December 2011. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- Schoenberger, Erica (2015). Nature, Choice and Social Power. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-415-83386-8.

The graves at Varna range from poor to richly endowed, suggesting a rather high degree of social differentiation. Their discovery has led to a re-evaluation of the form of social organization characteristic of the Varna culture and of the onset of social stratification in Neolithic cultures.

- Crampton 1987, p. 1.

- "Bulgar". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Boardman, John; Edwards, I.E.S.; Sollberger, E. (1982). The Cambridge Ancient History – part 1: The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0521224963.

Yet we cannot identify the Thracians at that remote period, because we do not know for certain whether the Thracian and Illyrian tribes had separated by then. It is safer to speak of Proto-Thracians from whom there developed in the Iron Age

- Allcock, John B. "Balkans". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Kidner, Frank (2013). Making Europe: The Story of the West. Cengage Learning. p. 57. ISBN 978-1111841317.

- Roisman 2011, pp. 135–138, 343–345.

- Nagle, D. Brendan (2006). Readings in Greek History: Sources and Interpretations. Oxford University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0199978458.

However, one of the Thracian tribes, the Odrysians, succeeded in unifying the Thracians and creating a powerful state

- Ashley, James R. (1998). The Macedonian Empire: The Era of Warfare Under Philip II and Alexander the Great, 359–323 B.C. McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 139–140. ISBN 978-0786419180.

- O Hogain, Daithi (2002). The Celts: A History. The Boydell Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0851159232.

- Gagarin, Michael, ed. (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6.

- "Ulfilas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- Bell, John D. "The Beginnings of Modern Bulgaria". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Singleton, Fred; Fred, Singleton (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9780521274852.

- Fouracre, Paul; McKitterick, Rosamond; Reuter, Timothy; Abulafia, David; Luscombe, David Edward; Allmand, C.T.; Riley-Smith, Jonathan; Jones, Michael (1995). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 1, c. 500 – c. 700. Cambridge University Press. p. 524. ISBN 9780521362917.

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700 (PDF). Cambridge University Press. pp. 311–334. ISBN 9781139428880. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- MacDermott 1998, p. 19.

- Detrez, Raymond (2014). Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 5. ISBN 978-1442241794.

- Parry, Ken, ed. (2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 48. ISBN 978-1444333619.

The conquest of the Balkans and the rise of the Bulgarian Empire was not a disaster for the indigenous population and its material and spiritual culture. The settlers and the local Romanized or semi-Romanized Thraco-Illyrian Christians influenced each other's way of life and socio-economic organization, as well as each other's cultures, language and religious outlook.

- Wolfram, Herwig (1990). History of the Goths. University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0520069831.

- Zlatarski, Vasil (1938). История на Първото българско Царство. I. Епоха на хуно–българското надмощие (679–852) [History of the First Bulgarian Empire. Period of Hunnic-Bulgarian domination (679–852)] (in Bulgarian). Marin Drinov Publishing House. p. 188. ISBN 978-9544302986. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Fine, John V.A.; Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. pp. 68–70. ISBN 978-0472081493.

- Vlasto, Alexis P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs Into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0521074599.

- "Krum". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Bell, John D. "The Spread of Christianity". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Crampton 2007, pp. 12–13.

- Bell, John D. "Reign of Simeon I". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

Bulgaria's conversion had a political dimension, for it contributed both to the growth of central authority and to the merging of Bulgars and Slavs into a unified Bulgarian people.

- The First Golden Age.

- Browning, Robert (1975). Byzantium and Bulgaria. Temple Smith. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0520026704.

- "Samuel". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- Scylitzae, Ioannis (1973). Synopsis Historiarum. Corpus Fontium Byzantiae Historiae. De Gruyter. p. 457. ISBN 978-3-11-002285-8.

- Crampton 1987, p. 4.

- Cameron, Averil (2006). The Byzantines. Blackwell Publishing. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4051-9833-2.

- Ostrogorsky, Georgije (1969). History of the Byzantine State. Rutgers University Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0813511986.

- Bell, John D. "Bulgaria – Second Bulgarian Empire". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Bourchier, James (1911). "History of Bulgaria". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Crampton 1987, p. 6.

- Martin, Michael (2017). City of the Sun: Development and Popular Resistance in the Pre-Modern West. Algora Publishing. p. 344. ISBN 978-1628942798.

- Bell, John D. "Bulgaria – Ottoman rule". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

The Bulgarian nobility was destroyed—its members either perished, fled, or accepted Islam and Turkicization—and the peasantry was enserfed to Turkish masters.

- Guineva, Maria (10 October 2011). "Old Town Sozopol – Bulgaria's 'Rescued' Miracle and Its Modern Day Saviors". Novinite. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Jireček, K.J. (1876). Geschichte der Bulgaren [History of the Bulgarians] (in German). Nachdr. d. Ausg. Prag. p. 88. ISBN 978-3487064086.

- Minkov, Anton (2004). Conversion to Islam in the Balkans: Kisve Bahası – Petitions and Ottoman Social Life, 1670–1730. Brill. p. 193. ISBN 978-9004135765.

- Detrez, Raymond (2008). Europe and the Historical Legacies in the Balkans. Peter Lang Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 978-9052013749.

- Fishman, Joshua A. (2010). Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: Disciplinary and Regional Perspectives. Oxford University Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-0195374926. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

There were almost no remnants of a Bulgarian ethnic identity; the population defined itself as Christians, according to the Ottoman system of millets, that is, communities of religious beliefs. The first attempts to define a Bulgarian ethnicity started at the beginning of the 19th century.

- Roudometof, Victor; Robertson, Roland (2001). Nationalism, Globalization, and Orthodoxy: The Social Origins of Ethnic Conflict in the Balkans. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 68–71. ISBN 978-0313319495.

- Crampton 1987, p. 8.

- Carvalho, Joaquim (2007). Religion and Power in Europe: Conflict and Convergence. Edizioni Plus. p. 261. ISBN 978-8884924643.

- Bell, John D. "Bulgaria – Ottoman administration". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- The Final Move to Independence.

- "Reminiscence from Days of Liberation*". Novinite. 3 March 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- "Shipka Pass". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- San Stefano, Berlin and Independence.

- Blamires, Cyprian (2006). World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 107. ISBN 978-1576079409.

The "Greater Bulgaria" re-established in March 1878 on the lines of the medieval Bulgarian empire after liberation from Turkish rule did not last long.

- "On March 3 Bulgaria celebrates National Liberation Day". Radio Bulgaria. 3 March 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Timeline: Bulgaria – A chronology of key events". BBC News. 6 May 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- Historical Setting.

- Crampton 2007, p. 174.

- Pinon, Rene (1913). L'Europe et la Jeune Turquie: Les Aspects Nouveaux de la Question d'Orient [Europe and Young Turkey: The new aspects of the Eastern Question] (in French). Perrin et cie. p. 411. ISBN 978-1-144-41381-9.

On a dit souvent de la Bulgarie qu'elle est la Prusse des Balkans

- Tucker, Spencer C; Wood, Laura (1996). The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 173. ISBN 978-0815303992.

- Broadberry, Stephen; Klein, Alexander (8 February 2008). "Aggregate and Per Capita GDP in Europe, 1870–2000: Continental, Regional and National Data with Changing Boundaries" (PDF). Centre for Economic Policy Research. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "WWI Casualty and Death Tables". PBS. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Mintchev, Veselin (October 1999). "External Migration in Bulgaria". South-East Europe Review (3/99): 124. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Chenoweth, Erica (2010). Rethinking Violence: States and Non-State Actors in Conflict. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-262-01420-5.

- Bulgaria in World War II: The Passive Alliance.

- Wartime Crisis.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. Columbia University Press. pp. 238–240. ISBN 978-0199326631.

When Bulgaria switched sides in September

- The Soviet Occupation.

- Valentino, Benjamin A. (2005). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the Twentieth Century. Cornell University Press. pp. 91–151. ISBN 978-0-8014-3965-0.

- Stankova, Marietta (2015). Bulgaria in British Foreign Policy, 1943–1949. Anthem Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-78308-430-2.

- Neuburger, Mary C. (2013). Balkan Smoke: Tobacco and the Making of Modern Bulgaria. Cornell University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8014-5084-6.

- Crampton 2005, p. 271.

- Domestic Policy and Its ResultsQuote: "real wages increased 75 percent, consumption of meat, fruit, and vegetables increased markedly, medical facilities and doctors became available to more of the population"

- After Stalin.

- The Economy.

- Stephen Broadberry; Alexander Klein (27 October 2011). "Aggregate and per capita GDP in Europe, 1870–2000" (PDF). pp. 23, 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- Vachkov, Daniel; Ivanov, Martin (2008). Българският външен дълг 1944–1989: Банкрутът на комунистическата икономика [Bulgarian Foreign Debt 1944–1989]. Siela. pp. 103, 153, 191. ISBN 978-9542803072.

- The Political Atmosphere in the 1970s.

- Bulgaria in the 1980s.

- Bohlen, Celestine (17 October 1991). "Vote Gives Key Role to Ethnic Turks". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

in 1980s ... the Communist leader, Todor Zhivkov, began a campaign of cultural assimilation that forced ethnic Turks to adopt Slavic names, closed their mosques and prayer houses and suppressed any attempts at protest. One result was the mass exodus of more than 300,000 ethnic Turks to neighboring Turkey in 1989

- Mudeva, Anna (31 May 2009). "Cracks show in Bulgaria's Muslim ethnic model". Reuters. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- Government and Politics.

- "Bulgarian Politicians Discuss First Democratic Elections 20y After". Novinite. 5 July 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- https://www.parliament.bg/en/const/

- Prodanov, Vasil (1 October 2007). "Разрушителният български преход" [The destructive Bulgarian transition]. Le Monde diplomatique (in Bulgarian). Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- Library of Congress 2006, p. 16.

- "Human Development Index Report" (PDF). United Nations. 2005. p. 224. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- "NATO Update: Seven new members join NATO". NATO. 29 March 2004. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- Castle, Steven (29 December 2006). "The Big Question: With Romania and Bulgaria joining the EU, how much bigger can it get?". The Independent. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- "Bulgaria Absolutely Ready to Take Over EU Presidency, Minister Says". Bulgarian Telegraph Agency. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Library of Congress 2006, p. 4.

- "Country comparison: Area". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "Bulgaria". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Topography.

- NSI Brochure 2018, pp. 2–3.

- "Bulgaria Second National Communication" (PDF). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Climate.

- "Характеристика на флората и растителността на България". Bulgarian-Swiss Program For Biodiversity. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- "Видово разнообразие на България" [Species biodiversity in Bulgaria] (PDF) (in Bulgarian). UNESCO report. 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- NSI Brochure 2018, p. 29.

- Belev, Toma (June 2010). "Бъдещето на природните паркове в България и техните администрации" [The future of Bulgaria's natural parks and their administrations]. Gora Magazine. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- "Europe & North America: 297 biosphere reserves in 36 countries". UNESCO. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "Bulgaria's biodiversity at risk" (PDF). IUCN Red List. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- NSI Brochure 2018, p. 3.

- Bell, John D. "Bulgaria: Plant and animal life". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Denchev, Cvetomir. "Checklist of the larger basidiomycetes ın Bulgaria" (PDF). Institute of Botany, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- "Bulgaria – Environmental Summary, UNData, United Nations". United Nations. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- "Biodiversity in Bulgaria". GRID-Arendal. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- "Report on European Environment Agency about the Nature protection and biodiversity in Europe". European Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- "Bulgaria Achieves Kyoto Protocol Targets – IWR Report". Novinite. 11 August 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- "Bulgaria". Environmental Performance Index/Yale University. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- Hakim, Danny (15 October 2013). "Bulgaria's Air Is Dirtiest in Europe, Study Finds, Followed by Poland". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- "High Air Pollution to Close Downtown Sofia". Novinite. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- "Bulgaria's Sofia, Plovdiv Suffer Worst Air Pollution in Europe". Novinite. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- "Industrial facilities causing the highest damage costs to health and the environment". European Environment Agency. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- "Bulgaria's quest to meet the environmental acquis". European Stability Initiative. 10 December 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- "Report on European Environment Agency about the quality of freshwaters in Europe". European Environment Agency. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- Library of Congress 2006, p. 17.

- Library of Congress 2006, pp. 16–17.

- "Fitch: Early Bulgaria Elections Would Create Fiscal Uncertainty". Reuters. 23 November 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Barzachka, Nina (25 April 2017). "Bulgaria's government will include far-right nationalist parties for the first time". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- "Bulgarian Cabinet Faces No-Confidence Vote Over Atomic Plant". Bloomberg Businessweek. 6 April 2012. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- Cage, Sam. "Bulgarian government resigns amid growing protests". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- Petkova, Mariya (21 February 2013). "Protests in Bulgaria and the new practice of democracy". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Tsolova, Tsvetelia (12 May 2013). "Rightist GERB holds lead in Bulgaria's election". Reuters. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- "PM Hopeful: New Bulgarian Cabinet Will Be 'Expert, Pragmatic'". Novinite. 25 May 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- Buckley, Neil (29 May 2013). "Bulgaria parliament votes for a 'Mario Monti' to lead government". The Financial Times. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Seiler, Bistra (26 June 2013). "Bulgarians protest government of 'oligarchs'". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- "Timeline of Oresharski's Cabinet: A Government in Constant Jeopardy". Novinite. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- "Bulgaria's Plamen Oresharski resigns". Novinite. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.