Persecution of Eastern Orthodox Christians

Persecution of Eastern Orthodox Christians is the persecution faced by church, clergy and adherents of the Eastern Orthodox Church (Orthodox Christianity) because of religious beliefs and practices. Orthodox Christians have been persecuted in various periods when under the rule of non-Orthodox Christian political structures. In modern times, anti-religious political movements and regimes in some countries have held an anti-Orthodox stance.

| Freedom of religion | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Status by country

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Religion portal | ||||||||||||

Catholic activities in Early modern Europe

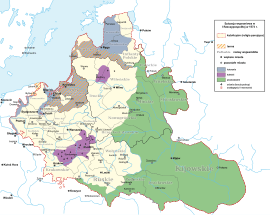

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

During the end off 16th century, under the influence of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, rising pressures towards Orthodox Christians in White Ruthenia and other Eastern parts of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth led to the enforcement of the Union of Brest in 1595-96. Until that time, most Belarusians and Ukrainians who lived under the rule of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were Orthodox Christians. Pressed by the state authorities, their hierarchs gathered in synod in the city of Brest and composed 33 articles of Union, which were accepted by the Roman Catholic Church.

At first, the Union appeared to be successful, but soon it lost much of its initial support,[1] mainly due to its forceful implementation on the Orthodox parishes and subsequent persecution of all who did not want to accept the Union. Enforcement of the Union stirred several massive uprisings, particularly the Khmelnytskyi Uprising, of the Zaporozhian Cossacks and together alliance of Ukrainian Catholics and Belarussian-Ukrainian Orthodox because of which the Commonwealth lost Left-bank Ukraine.

In 1656, Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch Macarios III Zaim lamented over the atrocities committed by the Polish Catholics against followers of Eastern Orthodoxy in various parts of Ukraine. Macarios was quoted as stating that seventeen or eighteen thousand followers of Eastern Orthodoxy were killed under hands of the Catholics, and that he desired Ottoman sovereignty over Catholic subjugation, stating:

God perpetuate the empire of the Turks for ever and ever! For they take their impost, and enter no account of religion, be their subjects Christians or Nazarenes, Jews or Samaritians; whereas these accursed Poles were not content with taxes and tithes from the brethren of Christ...[2]

Habsburg Monarchy

Since the many migrations of Serbs (predominantly and traditionally Eastern Orthodox) into the Habsburg Monarchy beginning in the 16th century, there were efforts to Catholicize the community. The Orthodox Eparchy of Marča became the Catholic Eparchy of Križevci after waves of Uniatization in the 17th and 18th centuries.[3] Notable individuals active in the Catholicisation of Serbs in the 17th century include Martin Dobrović, Benedikt Vinković, Petar Petretić, Rafael Levaković, Ivan Paskvali and Juraj Parčić.[3][4][5] Catholic bishops Vinković and Petretić wrote numerous inaccurate texts meant to incite hatred against Serbs and Orthodox Christians, some of which included advice on how to Catholicize the Serbs.[6]

Persecution in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire grouped the Orthodox Christians into the Rum Millet. In tax registries, Christians were recorded as "infidels" (see giaour).[7] After the Great Turkish War (1683–99), relations between Muslims and Christians in the European provinces of the Ottoman Empire were radicalized, gradually taking more extreme forms and resulting in occasional calls of Muslim religious leaders for expulsion or extermination of local Christians, and also Jews. As a result of Ottoman oppression, destruction of churches and violence against the non-Muslim civilian population, Serbs and their church leaders headed by Serbian Patriarch Arsenije III sided with the Austrians in 1689, and again in 1737 under Serbian Patriarch Arsenije IV, in war. In the following punitive campaigns, Ottoman forces conducted atrocities, resulting in the "Great Migrations of the Serbs".[8] In retaliation of the Greek rebellion, Ottomans authorities orchestrated massacres of Greeks in Constantinople in 1821.

During the Bulgarian Uprising (1876) and Russo-Turkish War (1877-78), persecution of Bulgarian Christian population was conducted by Turkish soldiers who massacred civilians, mainly in the regions of Panagurishte, Perushtitza, Bratzigovo, and Batak (see Batak massacre).[9]

Interwar period

The eastern part of Poland has a long history of Catholic–Orthodox rivalry.[10] The Roman Catholic clergy in the Chełm region in Poland was unambiguously anti-Orthodox in the Interwar period.[11][12][13] Ukraine, which has been a religious borderland, has a long history of religious conflict.[14]

World War II

Persecution of Serbs

The Croatian fascist Ustashe created the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) four days after the German invasion of Yugoslavia. Croatia was set up as an Italian protectorate. Around a third of the population was Orthodox (ethnic Serbs). The Ustashe followed Nazi ideology, and set up a goal of creating an ethnically pure Greater Croatia; Jews, Gypsies and especially Serbs were targeted and victims of genocidal policies.[15] The Ustashe recognized both Roman Catholicism and Islam as the national religions of Croatia, but held the position that Eastern Orthodoxy, as a symbol of Serb identity, was a dangerous foe.[16] In the spring and summer of 1941 the genocide against Orthodox Serbs began and concentration camps like Jasenovac were created. Serbs were murdered and forcibly converted, in order to Croatize,[16] and permanently destroy the Serbian Orthodox Church.[17] The Catholic leadership in Croatia mostly supported the Ustashe actions.[16][18] Orthodox bishops and priests were persecuted, arrested and tortured or killed (several hundreds) and hundreds (most[17]) of Orthodox churches were closed, destroyed, or plundered by the Ustashe.[16] Sometimes entire villages were locked inside the local Orthodox church and then set alight.[15] Hundreds of thousands of Orthodox Serbs were forced to flee from Ustashe-held territories into territory of German-occupied Serbia.[18] It was not until the end of the war that the Serbian Orthodox Church would function again in western parts of Yugoslavia.

The persecution of Orthodox priests in World War II increased the popularity of the Orthodox Church in Serbia.[19]

Contemporary

At the Orthodox conference in Istanbul on 12–15 March 1992, the church leaders issued a statement:[20]

After the collapse of the godless communist system that severely persecuted Orthodox Churches, we expected fraternal support or at least understanding for grave difficulties that had befallen us ... Instead, Orthodox countries have been targeted by Roman Catholic missionaries and advocates of Uniatism. These came together with Protestant fundamentalists ... and sects

Former Yugoslavia

Some Serbs viewed the Catholic leadership's support for political division along ethnic and religious lines in Croatia during the Wars in Yugoslavia, and support for the Albanian cause in Kosovo as anti-Serb and anti-Orthodox.[21] Yugoslav propaganda during the Milošević regime portrayed Croatia and Slovenia as part of an anti-Orthodox "Catholic alliance".[22]

Russia

Russian nationalists view the United States as the centre of Western anti-Russian, anti-Slavic and anti-Orthodox 'conspiracy that aims to destroy Russia', and has used the NATO intervention in the Bosnian War (1992–95) as an argument for this.[23]

In 1998 and 2000, in various towns in Russia, Orthodox fundamentalists accused texts written by liberal Orthodox theologicians of being "anti-Orthodox" and destroyed them in a public book burning.[24]

References

- Dvornik, Francis (1962). The Slavs in European history and civilization (3rd. pbk. ed.). New Brunswick [u.a.]: Rutgers University Press. p. 347. ISBN 9780813507996.

- The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pp. 134–135

- Kašić, Dušan Lj (1967). Srbi i pravoslavlje u Slavoniji i sjevernoj Hrvatskoj. Savez udruženja pravosl. sveštenstva SR Hrvatske. p. 49.

- Kolarić, Juraj (2002). Povijest kršćanstva u Hrvata: Katolička crkva. Hrvatski studiji Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. p. 77. ISBN 978-953-6682-45-4.

- Dimitrijević, Vladimir (2002). Pravoslavna crkva i rimokatolicizam: (od dogmatike do asketike). LIO. p. 337.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gavrilović, Slavko (1993). Iz istorije Srba u Hrvatskoj, Slavoniji i Ugarskoj: XV-XIX vek. Filip Višnjić. p. 30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. Brill. 13 June 2013. p. 44. ISBN 978-90-04-25076-5.

In the Ottoman defters, Orthodox Christians are as a rule recorded as kâfir or gâvur (infidels) or (u)rum.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History behind the Name. London: Hurst & Company. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9781850654773.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Sorokowski, A. (1986). "Ukrainian catholics and orthodox in Poland since 1945". Religion in Communist Lands. 14 (3): 244–261. doi:10.1080/09637498608431268.

- Sadkowski, K. (1998). "From Ethnic Borderland to Catholic Fatherland: The Church, Christian Orthodox, and State Administration in the Chelm Region, 1918-1939". Slavic Review. 57 (4): 813–839. doi:10.2307/2501048. JSTOR 2501048.

- Wynot, E.D., Jr. (1997). "Prisoner of history: the Eastern Orthodox Church in Poland in the twentieth century". J. Church & St. 39: 319–.

- Sadkowski, K. (1998). "Religious Exclusion and State Building: The Roman Catholic Church and the Attempted Revival of Greek Catholicism in the Chelm Region, 1918-1924". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 22: 509–526.

- Lami, G. (2007). "The Greek-catholic Church in Ukraine during the first half of the 20th Century". In Carvalho, Joaquim (ed.). Religion and Power in Europe: Conflict and Convergence. Edizioni Plus. pp. 235–. ISBN 978-88-8492-464-3.

- Paul Roe (2 August 2004). Ethnic Violence and the Societal Security Dilemma. Routledge. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-1-134-27689-9.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. New York: Indiana University Press. pp. 118–125. ISBN 0-253-34656-8.

- Rory Yeomans (2015). The Utopia of Terror: Life and Death in Wartime Croatia. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 178–. ISBN 978-1-58046-545-8.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. 2. San Francisco, CA: Stanford University Press. pp. 531–532, 546, 570–572. ISBN 0-8047-3615-4.

- Ken Parry (10 May 2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.

- Vjekoslav Perica (2002). Balkan Idols: Religion and Nationalism in Yugoslav States. Oxford University Press. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-19-517429-8.

- Paul Mojzes (6 October 2016). Yugoslavian Inferno: Ethnoreligious Warfare in the Balkans. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-1-4742-8838-5.

- Kemal Kurspahić (2003). Prime Time Crime: Balkan Media in War and Peace. US Institute of Peace Press. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-1-929223-39-8.

- Paul Hollander (2005). Understanding anti-Americanism: its origins and impact. Capercaillie. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-9549625-7-9.

- Stephen Shenfield (8 July 2016). Russian Fascism: Traditions, Tendencies and Movements. ISBN 9781315500034.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anti-Orthodox sentiment. |

- Dionisije Milivojevich (1945). The Persecution of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Yugoslavia. Serbian Orthodox Monastery of St. Sava.

- Michael Bourdeaux (1970). Patriarch and Prophets: Persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church Today. Praeger.