Decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent

The decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent refers to a gradual process of dwindling and replacement of Buddhism in India, which ended around the 12th century.[1][2] According to Lars Fogelin, this was "not a singular event, with a singular cause; it was a centuries-long process."[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

|

The decline of Buddhism has been attributed to various factors, especially the regionalisation of India after the end of the Gupta Empire (320–650 CE), which led to the loss of patronage and donations as Indian dynasties turned to the services of Hindu Brahmins. Another factor was invasions of north India by various groups such as Huns, Turco-Mongols and Persians and subsequent destruction of Buddhist institutions such as Nalanda and religious persecutions.[4] Religious competition with Hinduism and later Islam were also important factors. Islamization of Bengal and demolitions of Nalanda, Vikramasila and Odantapuri by Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, a general of the Delhi Sultanate are thought to have severely weakened the practice of Buddhism in East India.[5]

The total Buddhist population in 2010 in the Indian subcontinent – excluding that of Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan – was about 10 million, of which about 7.2% lived in Bangladesh, 92.5% in India and 0.2% in Pakistan.[6]

Growth of Buddhism

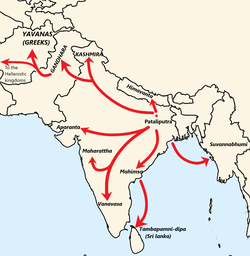

Buddhism expanded in the Indian subcontinent in the centuries after the death of the Buddha, particularly after receiving the endorsement and royal support of the Maurya Empire under Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE. It spread even beyond the Indian subcontinent to Central Asia and China.

The Buddha's period saw not only urbanisation, but also the beginnings of centralised states.[7] The successful expansion of Buddhism depended on the growing economy of the time, together with increased centralised political organisation capable of change.[8]

Buddhism spread across ancient India and state support by various regional regimes continued through the 1st-millennium BCE.[9] The consolidation of the monastic organisation made Buddhism the centre of religious and intellectual life in India.[10] .The succeeding Kanva Dynasty had four Buddhist Kanva Kings.[11]

Gupta Dynasty (4th-6th century)

Religious developments

During the Gupta dynasty (4th to 6th century), Mahayana Buddhism turned more ritualistic, while Buddhist ideas were adopted into Hindu schools. The differences between Buddhism and Hinduism blurred, and Vaishnavism, Shaivism and other Hindu traditions became increasingly popular, while Brahmins developed a new relationship with the state.[12] As the system grew, Buddhist monasteries gradually lost control of land revenue. In parallel, the Gupta kings built Buddhist temples such as the one at Kushinagara,[13][14] and monastic universities such as those at Nalanda, as evidenced by records left by three Chinese visitors to India.[15][16][17]

Hun Invasions (6th century)

Chinese scholars traveling through the region between the 5th and 8th centuries, such as Faxian, Xuanzang, Yijing, Hui-sheng, and Sung-Yun, began to speak of a decline of the Buddhist Sangha in the Northwestern parts of Indian subcontinent, especially in the wake of the Hun invasion from central Asia in the 6th century CE.[4] Xuanzang wrote that numerous monasteries in north-western India had been reduced to ruins by the Huns.[4][18]

The Hun ruler Mihirakula, who ruled from 515 CE in north-western region (modern Afghanistan, Pakistan and north India), suppressed Buddhism as well. He did this by destroying monasteries as far away as modern-day Prayagraj.[19] Yashodharman and Gupta Empire rulers, in and after about 532 CE, reversed Mihirakula's campaign and ended the Mihirakula era.[20][21]

According to Peter Harvey, the religion recovered slowly from these invasions during the 7th century, with the "Buddhism of southern Pakistan remaining strong."[22] The reign of the Pala Dynasty (8th to 12th century) saw Buddhism in North India recover due to royal support from the Palas who supported various Buddhist centers like Nalanda. By the eleventh century, Pala rule had weakened, however.[22]

Socio-political change and religious competition

The regionalisation of India after the end of the Gupta Empire (320–650 CE) led to the loss of patronage and donations.[24] The prevailing view of decline of Buddhism in India is summed by A.L. Basham's classic study which argues that the main cause was the rise of an ancient Hindu religion again, "Hinduism", which focused on the worship of deities like Shiva and Vishnu and became more popular among the common people while Buddhism, being focused on monastery life, had become disconnected from public life and its life rituals, which were all left to Hindu Brahmins.[25]

Religious competition

The growth of new forms of Hinduism (and to a lesser extent Jainism) was a key element in the decline in Buddhism in India, particularly in terms of diminishing financial support to Buddhist monasteries from laity and royalty.[26][27][28] According to Hazra, Buddhism declined in part because of the rise of the Brahmins and their influence in socio-political process.[29][note 1]

The disintegration of central power also led to regionalisation of religiosity, and religious rivalry.[33] Rural and devotional movements arose within Hinduism, along with Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Bhakti and Tantra,[33] that competed with each other, as well as with numerous sects of Buddhism and Jainism.[33][34] This fragmentation of power into feudal kingdoms was detrimental for Buddhism, as royal support shifted towards other communities and Brahmins developed a strong relationship with Indian states.[24][35][26][27][28][29]

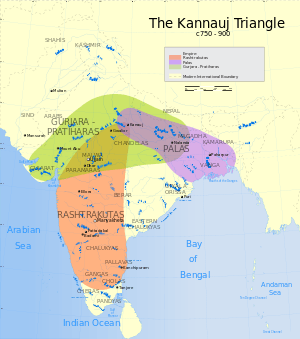

Over time the new Indian dynasties which arose after the 7th and 8th centuries tended to support the Brahmanical ideology and Hinduism, and this conversion proved decisive. These new dynasties, all of which supported Brahmanical Hinduism, include "the Karkotas and Pratiharas of the north, the Rashtrakutas of the Deccan, and the Pandyas and Pallavas of the south" (the Pala Dynasty is one sole exception to these).[36] One of the reasons of this conversion was that the brahmins were willing and able to aid in local administration, and they provided councillors, administrators and clerical staff.[37][38] Moreover, brahmins had clear ideas about society, law and statecraft (and studied texts such as the Arthashastra and the Manusmriti) and could be more pragmatic than the Buddhists, whose religion was based on monastic renunciation and did not recognize that there was a special warrior class that was divinely ordained to use violence.[39] As Johannes Bronkhorst notes, Buddhists could give "very little" practical advice in response to that of the Brahmins and Buddhist texts often speak ill of kings and royalty.[40]

The persecution of Buddhism started as early as in life or soon after the death of King Ashoka (Gonandiya). D.N. Jha writes that according to Kashmiri texts dated to the 12th century, Ashoka's Son Jalauka was Shaivite and was responsible for the destruction of many Buddhist monasteries.[7] The story of Jalauka is essentially legendary, and no independent corroboration of the Kashmir tradition has been discovered.[8] Patanjali, a famous grammarian stated in his Mahabhashya that Brahmins and Sharamanas (Buddhists) were eternal enemies[9] With the emergence of Hindu rulers of the Gupta Empire, Hinduism saw major revivalism in the Indian subcontinent which challenged Buddhism which was at that time at its zenith. Even though the Gupta Empire was tolerant towards Buddhism and patronized Buddhist arts and religious institutions, Hindu revivalism generally became a major threat to Buddhism which led to its decline. A Buddhist illustrated palm-leaf manuscript from the Pala period (one of the earliest Indian illustrated manuscripts to survive in modern times) is preserved in University of Cambridge library. Composed in the year 1015, the manuscript contains a note from the year 1138 by a Buddhist believer called Karunavajra which indicates that without his efforts, the manuscript would have been destroyed during a political struggle for power. The note states that 'he rescued the 'Perfection of Wisdom, incomparable Mother of the Omniscient' from falling into the hands of unbelievers (who according to Camillo Formigatti were most probably people of Brahmanical affiliation).[10] In 1794 Jagat Singh, Dewan (minister) of Raja Chet Singh of Banaras began excavating two pre Ashokan era stupas at Sarnath for construction material. Dharmarajika stupa was completely demolished and only its foundation exists today while Dhamekh stupa incurred serious damage. During excavation, a green marble relic casket was discovered from Dharmarajika stupa which contained Buddha's ashes was subsequently thrown into the Ganges river by Jagat Singh according to his Hindu faith. The incident was reported by a British resident and timely action of British authorities saved Dhamekh Stupa from demolition.[11]

Omvedt states that while Buddhist institutions tended to be less involved in politics, Hindu brahmins provided numerous services for Indian royalty:

At the higher level they provided legitimacy by creating genealogies and origin mythologies identifying the kings as Kshatriyas and organising impressive ceremonial functions that invested the king with all the paraphernalia and mystique of Hindu royalty; at the lower level they propagandised the mystique of social supremacy and political power. They taught the population, they established ritual and priestly relations with the prominent households of the region, they promulgated caste and the rights of kings.[37]

Bronkhorst notes that some of the influence of the brahmins also derived from the fact that they were seen as powerful, because of their use of incantations and spells (mantras) as well as other sciences like astronomy, astrology, calendrics and divination. Many Buddhists refused to use such "sciences" and left them to brahmins, who also performed most of the rituals of the Indian states (as well as in places like Cambodia and Burma).[41] This eventually led to further challenges for Buddhists:

Rulers gave financial support to Brahmans, took the responsibility of enforcing varna laws and discriminating against ‘heretical’ sects, and refused state protection to their persons and property—if they did not actively murder and loot them themselves.[42]

Lars Fogelin argues that the concentration of the sangha into large monastic complexes like Nalanda was one of the contributing causes for the decline. He states that the Buddhists of these large monastic institutions became "largely divorced from day-to-day interaction with the laity, except as landlords over increasingly large monastic properties."[43] Padmanabh Jaini also notes that Buddhist laypersons are relatively neglected in the Buddhist literature, which produced only one text on lay life and not until the 11th century, while Jains produced around fifty texts on the life and conduct of a Jaina layperson.[44] These factors all slowly led to the replacement of Buddhism in the South and West of India by Hinduism and Jainism. Fogelin states that

While some small Buddhist centers still persisted in South and West India in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, for the most part, both monastic and lay Buddhism had been eclipsed and replaced by Hinduism and Jainism by the end of the first millennium ce.[45]

Buddhist sources also mention violence against Buddhists by Hindu brahmins and kings. Hazra mentions that the eighth and ninth centuries saw "Brahminical hostilities towards Buddhism in South India."[46] Xuanzang for example, mentions the destruction of Buddhist images by the Shaivite king Sashanka and Taranatha also mentions the destruction of temples by Brahmins.[47]

Religious convergence and absorption

_(14487936463).jpg)

Buddhism's distinctiveness also diminished with the rise of Hindu sects. Though Mahayana writers were quite critical of Hinduism, the devotional cults of Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism likely seemed quite similar to laity, and the developing Tantrism of both religions were also similar.[48] Also, "the increasingly esoteric nature" of both Hindu and Buddhist tantrism made it "incomprehensible to India's masses," for whom Hindu devotionalism and the worldly power-oriented Nath Siddhas became a far better alternative.[49][50][note 2] Buddhist ideas, and even the Buddha himself,[51] were absorbed and adapted into orthodox Hindu thought,[52][48][53] while the differences between the two systems of thought were emphasized.[54][55][56][57][58][59]

Elements which medieval Hinduism adopted during this time included vegetarianism, a critique of animal sacrifices, a strong tradition of monasticism (founded by figures such as Shankara) and the adoption of the Buddha as an avatar of Vishnu.[60] On the other end of the spectrum, Buddhism slowly became more and more "Brahmanized", initially beginning with the adoption of Sanskrit as a means to defend their interests in royal courts.[61] According to Bronkhorst, this move to the Sanskrit cultural world also brought with it numerous Brahmanical norms which now were adopted by the Sanskrit Buddhist culture (one example is the idea present in some Buddhist texts that the Buddha was a brahmin who knew the Vedas).[62] Bronkhorst notes that with time, even the caste system became widely accepted "by all practical purposes" by Indian Buddhists (this survives among the Newar Buddhists of Nepal).[63] Bronkhorst notes that eventually, a tendency developed to see Buddhism's past as having been dependent on Brahmanism and secondary to it. This idea, according to Bronkhorst, "may have acted like a Trojan horse, weakening this religion from within."[64]

The political realities of the period also led some Buddhists to change their doctrines and practices. For example, some later texts such as the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra and the Sarvadurgatipariśodhana Tantra begin to speak of the importance of protecting Buddhist teachings and that killing is allowed if necessary for this reason. Later Buddhist literature also begins to see kings as bodhisattvas and their actions as being in line with the dharma (Buddhist kings like Devapala and Jayavarman VII also claimed this).[65] Bronkhorst also thinks that the increase in the use of apotropaic rituals (including for the protection of the state and king) and spells (mantras) by 7th century Indian Buddhism is also a response to Brahmanical and Shaiva influence. These included fire sacrifices, which were performed under the rule of Buddhist king Dharmapala (r. c. 775–812).[66] Alexis Sanderson has shown that Tantric Buddhism is filled with imperial imagery reflecting the realities of medieval India, and that in some ways work to sanctify that world.[67] Perhaps because of these changes, Buddhism remained indebted to Brahmanical thought and practice now that it had adopted much of its worldview. Bronkhorst argues that these somewhat drastic changes "took them far from the ideas and practices they had adhered to during the early centuries of their religion, and dangerously close to their much-detested rivals."[68] These changes which brought Buddhism closer to Hinduism, eventually made it much easier for Buddhism to be absorbed into Hinduism.[48]

Patronage

In ancient India, regardless of the religious beliefs of their kings, states usually treated all the important sects relatively even-handedly.[9] This consisted of building monasteries and religious monuments, donating property such as the income of villages for the support of monks, and exempting donated property from taxation. Donations were most often made by private persons such as wealthy merchants and female relatives of the royal family, but there were periods when the state also gave its support and protection. In the case of Buddhism, this support was particularly important because of its high level of organisation and the reliance of monks on donations from the laity. State patronage of Buddhism took the form of land grant foundations.[69]

Numerous copper plate inscriptions from India as well as Tibetan and Chinese texts suggest that the patronage of Buddhism and Buddhist monasteries in medieval India was interrupted in periods of war and political change, but broadly continued in Hindu kingdoms from the start of the common era through the early first millennium CE.[70][71][72] The Gupta kings built Buddhist temples such as the one at Kushinagara,[73][14] and monastic universities such as those at Nalanda, as evidenced by records left by three Chinese visitors to India.[15][16][17]

Internal social-economic dynamics

According to some scholars such as Lars Fogelin, the decline of Buddhism may be related to economic reasons, wherein the Buddhist monasteries with large land grants focused on non-material pursuits, self-isolation of the monasteries, loss in internal discipline in the sangha, and a failure to efficiently operate the land they owned.[72][74] With the growing support for Hinduism and Jainism, Buddhist monasteries also gradually lost control of land revenue.

Islamic invasions and conquest (10th to 12th century)

Invasions

According to Peter Harvey:

From 986 CE, the Muslim Turks started raiding northwest India from Afghanistan, plundering western India early in the eleventh century. Forced conversions to Islam were made, and Buddhist images smashed, due to the Islamic dislike of idolatry. Indeed in India, the Islamic term for an 'idol' became 'budd'.

— Peter Harvey, An Introduction to Buddhism[76]

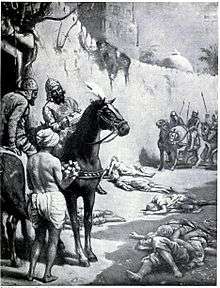

The Muslim conquest of the Indian subcontinent was the first great iconoclastic invasion into the Indian subcontinent.[77] The Persian traveller Al Biruni's memoirs suggest Buddhism had vanished from Ghazni (Afghanistan) and medieval Punjab region (northern Pakistan) by early 11th century.[78] By the end of twelfth century, Buddhism had further disappeared,[4][79] with the destruction of monasteries and stupas in medieval north-west and western Indian subcontinent (now Pakistan and north India).[80] The chronicler of Shahubuddin Ghori's forces records enthusiastically about attacks on the monks and students and victory against the non-Muslim infidels. The major centers of Buddhism were in north India and the direct path of the Muslim armies. As centers of wealth and non-Muslim religions they were targets[81] Buddhist sources agree with this assessment. Taranatha in his History of Buddhism in India of 1608,[82] gives an account of the last few centuries of Buddhism, mainly in Eastern India. Mahayana Buddhism reached its zenith during the Pala dynasty period, a dynasty that ended with the Islamic invasion of the Gangetic plains.[2]

According to William Johnston, hundreds of Buddhist monasteries and shrines were destroyed, Buddhist texts were burnt by the Muslim armies, monks and nuns killed during the 12th and 13th centuries in the Gangetic plains region.[83] The Islamic invasions plundered wealth and destroyed Buddhist images.[76]

The Buddhist university of Nalanda was mistaken for a fort because of the walled campus. The Buddhist monks who had been slaughtered were mistaken for Brahmins according to Minhaj-i-Siraj.[84] The walled town, the Odantapuri monastery, was also conquered by his forces. Sumpa basing his account on that of Śākyaśrībhadra who was at Magadha in 1200, states that the Buddhist university complexes of Odantapuri and Vikramshila were also destroyed and the monks massacred.[85] Muslim forces attacked the north-western regions of the Indian subcontinent many times.[86] Many places were destroyed and renamed. For example, Odantapuri's monasteries were destroyed in 1197 by Mohammed-bin-Bakhtiyar and the town was renamed.[87] Likewise, Vikramashila was destroyed by the forces of Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khilji around 1200.[88] Many Buddhist monks fled to Nepal, Tibet, and South India to avoid the consequences of war.[89] Tibetan pilgrim Chöjepal had to flee advancing Muslim troops multiple times, as they were sacking Buddhist sites.[90]

The north-west parts of the Indian subcontinent fell to Islamic control, and the consequent take over of land holdings of Buddhist monasteries removed one source of necessary support for the Buddhists, while the economic upheaval and new taxes on laity sapped the laity support of Buddhist monks.[74] Not all monasteries were destroyed by the invasions (Somapuri, Lalitagiri, Udayagiri), but since these large Buddhist monastic complexes had become dependent on the patronage of local authorities, when this patronage dissipated, they were abandoned by the sangha.[91]

In the north-western parts of medieval India, the Himalayan regions, as well as regions bordering central Asia, Buddhism once facilitated trade relations, states Lars Fogelin. With the Islamic invasion and expansion, and central Asians adopting Islam, the trade route-derived financial support sources and the economic foundations of Buddhist monasteries declined, on which the survival and growth of Buddhism was based.[74][92] The arrival of Islam removed the royal patronage to the monastic tradition of Buddhism, and the replacement of Buddhists in long-distance trade by the Muslims eroded the related sources of patronage.[80][92]

Decline under Islamic rule

After the conquest, Buddhism largely disappeared from most of India, surviving in the Himalayan regions and south India.[4][76][94] Abul Fazl stated that there was scarcely any trace of Buddhists left. When he visited Kashmir in 1597, he met with a few old men professing Buddhism, however, he 'saw none among the learned'.[95]

According to Randall Collins, Buddhism was already declining in India by the 12th century, but with the pillage by Muslim invaders it nearly became extinct in India in the 1200s.[96] In the 13th century, states Craig Lockard, Buddhist monks in India escaped to Tibet to escape Islamic persecution;[97] while the monks in western India, states Peter Harvey, escaped persecution by moving to south Indian Hindu kingdoms that were able to resist the Muslim power.[98]

Brief Muslim accounts and the one eye-witness account of Dharmasmavim in wake of the conquest during the 1230s talk about abandoned viharas being used as camps by the Turukshahs.[99] Later historical traditions such as Taranatha's are mixed with legendary materials and summarised as "the Turukshah conquered the whole of Magadha and destroyed many monasteries and did much damage at Nalanda, such that many monks fled abroad" thereby bringing about a demise of Buddhism with their destruction of the Viharas.[99]

While the Muslims sacked the Buddhists viharas, the temples and stupas with little material value survived. After the collapse of monastic Buddhism, Buddhist sites were abandoned or reoccupied by other religious orders. In the absence of viharas and libraries, scholastic Buddhism and its practitioners migrated to the Himalayas, China and Southeast Asia.[100] The devastation of agriculture also meant that many laypersons were unable to support Buddhist monks, who were easily identifiable and also vulnerable. As the Sangha died out in numerous areas, it lacked the ability to revive itself without more monks to perform ordinations. Peter Harvey concludes:

Between the alien Muslims, with their doctrinal justification of "holy war" to spread the faith, and Hindus, closely identified with Indian culture and with a more entrenched social dimension, the Buddhists were squeezed out of existence. Lay Buddhists were left with a folk form of Buddhism, and gradually merged into Hinduism, or converted to Islam. Buddhism, therefore, died out in all but the fringes of its homeland, though it had long since spread beyond it.[101]

Fogelin also notes that some elements of the Buddhist sangha moved to the Himalayas, China, and Southeast Asia, or they may have reverted to secular life or become wandering ascetics. In this environment, without monasteries and scholastic centers of their own, Buddhist ascetics and laypersons were eventually absorbed into the religious life of medieval India.[102]

Survival of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent

Buddhist institutions survived in eastern India right until the Islamic invasion. Buddhism still survives among the Barua (though practising Vaishnavite elements[103][104]), a community of Bengali Magadh descent who migrated to Chittagong region. Indian Buddhism also survives among Newars of Nepal, who practice unique form of Vajrayana known as Newar Buddhism.

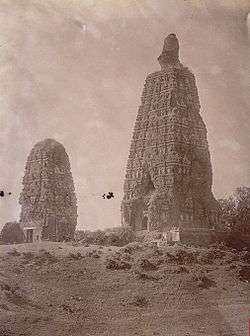

While the Buddhist monastic centers like Nalanda had been sacked, the temples and stupas at pilgrimage sites (such as Bodh Gaya) didn't receive the same treatment. The reason these were left unharmed was because they were "not material legitimations of rival royal families".[100] Inscriptions at Bodh Gaya show that the Mahabodhi temple was in some use till 14th century. According to the 17th century Tibetan Lama Taranatha's History of Buddhism in India, the temple was restored by a Bengali queen in the 15th century, later passing on to a landowner and becoming a Shaivite center.[100] Inscriptions at Bodh Gaya mention Buddhist pilgrims visiting it throughout the period of Buddhist decline:[105]

- 1302-1331: Several groups from Sindh

- 15th or 16th century: a pilgrim from Multan

- 2nd half of the 15th century, monk Budhagupta from South India

- 16th-century Abhayaraj from Nepal

- 1773 Trung Rampa, a representative of the Panchen Lama from Tibet, welcomed by Maharaja of Varanasi

- 1877, Burmese mission sent by King Mindon Min

Abul Fazl, the courtier of Mughal emperor Akbar, states, "For a long time past scarce any trace of them (the Buddhists) has existed in Hindustan." When he visited Kashmir in 1597 he met with a few old men professing Buddhism, however, he 'saw none among the learned'. This can also be seen from the fact that Buddhist priests were not present amidst learned divines that came to the Ibadat Khana of Akbar at Fatehpur Sikri.[95]

After the Islamization of Kashmir by sultans like Sikandar Butshikan, much of Hinduism was gone and a little of Buddhism remained. Fazl writes, "The third time that the writer accompanied His Majesty to the delightful valley of Kashmir, he met a few old men of this persuasion (Buddhism), but saw none among the learned."[106]

`Abd al-Qadir Bada'uni mentions, "Moreover samanis and Brahmans managed to get frequent private audiences with His Majesty." The term samani (Sanskrit: Sramana and Prakrit: Samana) refers to a devotee a monk. Irfan Habib states that while William Henry Lowe assumes the Samanis to be Buddhist monks, they were Jain ascetics.[107]

Taranatha's history which mentions Buddhist sangha surviving in some regions of India during his time[108] which includes Konkana, Kalinga, Mewad, Chittor, Abu, Saurastra, Vindhya mountains, Ratnagiri, Karnataka etc. A Jain author Gunakirti (1450-1470) wrote a Marathi text, Dhamramrita,[109] where he gives the names of 16 Buddhist orders. Dr. Johrapurkar noted that among them, the names Sataghare, Dongare, Navaghare, Kavishvar, Vasanik and Ichchhabhojanik still survive in Maharashtra as family names.[110]

Buddhism was virtually extinct in British Raj by the end of the 19th century, except its Himalayan region, east and some niche locations. According to the 1901 census of British India, which included modern Bangladesh, India, Burma, and Pakistan, the total population was 294.4 million, of which total Buddhists were 9.5 million. Excluding Burma's nearly 9.2 million Buddhists in 1901, this colonial-era census reported 0.3 million Buddhists in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan in the provinces, states and agencies of British India or about 0.1% of the total reported population.[111]

The 1911 census reported a combined Buddhist population in British India, excluding Burma, of about 336,000 or about 0.1%.[112]

.jpg) Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, was built in the 1600s, is the largest monastery in India and second-largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet.

Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, was built in the 1600s, is the largest monastery in India and second-largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet. Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim was built under the direction of Changchub Dorje, 12th Karmapa Lama in the mid-1700s.[113]

Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim was built under the direction of Changchub Dorje, 12th Karmapa Lama in the mid-1700s.[113]

Revival

In 1891, the Sri Lankan (Sinhalese) pioneering Buddhist activist Don David Hewavitarane later to be world-renowned as Anagarika Dharmapala visited India. His campaign, in cooperation with American Theosophists such as Henry Steel Olcott and Madame Blavatsky, led to the revival of Buddhist pilgrimage sites along with the formation of the Maha Bodhi Society and Maha Bodhi Journal. His efforts increased awareness and raised funds to recover Buddhist holy sites in British occupied India, such as the Bodh Gaya in India and those in Burma.[114]

In the 1950s, B. R. Ambedkar pioneered the Dalit Buddhist movement in India for the Dalits. Dr. Ambedkar, on 14 October 1956 in Nagpur converted to Buddhism along with his 365,000 followers. Many other such mass-conversion ceremonies followed.[115] Many converted employ the term "Navayana" (also known as "Ambedkarite Buddhism" or "Neo Buddhism") to designate the Dalit Buddhist movement, which started with Ambedkar's conversion.[116] Now Marathi Buddhist is the largest Buddhist community in India.

in 1959, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, escaped from Tibet to India along with numerous Tibetan refugees, and set up the government of Tibet in Exile in Dharamshala, India,[117] which is often referred to as "Little Lhasa", after the Tibetan capital city. Tibetan exiles numbering several thousand have since settled in the town. Most of these exiles live in Upper Dharamsala, or McLeod Ganj, where they established monasteries, temples, and schools. The town has become one of the centres of Buddhism in the world.

The Buddhist population in the modern era nation of India grew at a decadal rate of 22.5% between 1901 and 1981, due to birth rates and conversions, or about the same rate as Hinduism, Jainism and Sikhism, but faster than Christianity (16.8%), and slower than Islam (30.7%).[118]

According to a 2010 Pew estimate, the total Buddhist population had increased to about 10 million in the nations created from British India. Of these, about 7.2% lived in Bangladesh, 92.5% in India and 0.2% in Pakistan.[6]

See also

- Navayana

- History of Buddhism

- History of Buddhism in India

- Gautama Buddha in Hinduism

- History of India

- Buddhism in Kashmir

- Index of Buddhism-related articles

- Religion in India

- Muslim conquests of the Indian subcontinent

- Bodh Gaya

- Harsha of Kashmir

- Dalit Buddhist movement

- Gautama Buddha

- Ashoka

- Ambedkar

- Historical Jewish population comparisons

- Decline of Greco-Roman polytheism

- Secular Buddhism

Notes

- According to Randall Collins, Richard Gombrich and other scholars, Buddhism's rise or decline is not linked to Brahmins or the caste system, since Buddhism was "not a reaction to the caste system", but aimed at the salvation of those who joined its monastic order.[30][31][32]

- Elverskog is quoting David Gordon White (2012), The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India, p.7, who writes: "The thirty-six or thirty-seven metaphysical levels of being were incomprehensible to India's masses and held few answers to their human concerns and aspirations." Yet, White is writing here about Hindu tantrism, and states that only the Nath Siddhas remained attractive, because of their orientation on worldly power.

References

- Akira Hirakawa; Paul Groner (1993). A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 227–240. ISBN 978-81-208-0955-0.

- Damien Keown (2004). A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 208–209. ISBN 978-0-19-157917-2.

- Fogelin, Lars, An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism, Oxford University Press, p. 218.

- Wendy Doniger (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. pp. 155–157. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- Hartmut Scharfe (2002). Handbook of Oriental Studies. BRILL. p. 150. ISBN 90-04-12556-6.

Nalanda, together with the colleges at Vikramasila and Odantapuri, suffered gravely during the conquest of Bihar by the Muslim general Muhammad Bhakhtiyar Khalji between A.D. 1197 and 1206, and many monks were killed or forced to flee.

- Religion population totals in 2010 by Country Pew Research, Washington DC (2012)

- Richard Gombrich, A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 205.

- Richard Gombrich, A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 184.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 182.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 208.

- P. 53 History of India By Sir Roper Lethbridge

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 207-211.

- Gina Barns (1995). "An Introduction to Buddhist Archaeology". World Archaeology. 27 (2): 166–168.

- Robert Stoddard (2010). "The Geography of Buddhist Pilgrimage in Asia". Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art. Yale University Press. 178: 3–4.

- Hartmut Scharfe (2002). Handbook of Oriental Studies. BRILL Academic. pp. 144–153. ISBN 90-04-12556-6.

- Craig Lockard (2007). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: Volume I: A Global History. Houghton Mifflin. p. 188. ISBN 978-0618386123.

- Charles Higham (2014). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Infobase. pp. 121, 236. ISBN 978-1-4381-0996-1.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Historical Development of Buddhism in India - Buddhism under the Guptas and Palas". Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- Nakamura, Hajime (1980). Indian Buddhism: A Survey With Bibliographical Notes. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 146. ISBN 8120802721.

- Foreign Influence on Ancient India by Krishna Chandra Sagar p.216

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 242–244. ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4.

- Harvey, Peter, Introduction to Buddhism, p. 194.

- Fogelin, Lars, An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism, Oxford University Press, 204-205.

- Berkwitz 2012, p. 140.

- Omvedt, Gail, Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste, p. 160.

- Fogelin, Lars (2015). An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 218–9. ISBN 978-0-19-994823-9.

- Murthy, K. Krishna (1987). Glimpses of Art, Architecture, and Buddhist Literature in Ancient India. Abhinav Publications. p. 91. ISBN 978-81-7017-226-0.

- "BUDDHISM IN ANDHRA PRADESH". metta.lk. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- Kanai Lal Hazra (1995). The Rise And Decline Of Buddhism In India. Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 371–385. ISBN 978-81-215-0651-9.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 205-206

- Christopher S. Queen; Sallie B. King (1996). Engaged Buddhism: Buddhist Liberation Movements in Asia. State University of New York Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-7914-2844-3.

- Richard Gombrich (2012). Buddhist Precept & Practice. Routledge. pp. 344–345. ISBN 978-1-136-15623-6.

- Michaels 2004, p. 42.

- Inden 1978, p. 67.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, pages 189–190

- Omvedt, Gail, Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste, p. 172.

- Omvedt, Gail, Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste, p. 173.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 99.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 99-101.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 103.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 108.

- Omvedt, Gail, Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste, p. 171.

- Fogelin, Lars, An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism, Oxford University Press, p. 210.

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1980): “The disappearance of Buddhism and the survival of Jainism: a study in contrast.” Studies in History of Buddhism. Ed. A. K. Narain. Delhi: B. R. Publishing. Pp. 81–91. Reprint: Jaini, 2001: 139–53.

- Fogelin, Lars, An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism, Oxford University Press, p. 219.

- Kanai Lal Hazra (1995). The Rise And Decline Of Buddhism In India. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 356. ISBN 978-81-215-0651-9.

- Omvedt, Gail, Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste, p. 170.

- Peter Harvey, An Introduction to Buddhism. Cambridge University Press, 1990, page 140.

- Elverskog 2011, p. 95-96.

- White 2012, p. 7.

- Vinay Lal, Buddhism's Disappearance from India

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, pages 239–240.

- Govind Chandra Pande (1994). Life and thought of Śaṅkarācārya. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1104-1, ISBN 978-81-208-1104-1. Source: (accessed: Friday, March 19, 2010), p.255; "The relationship of Śaṅkara to Buddhism has been the subject of considerable debate since ancient times. He has been hailed as the arch critic of Buddhism and the principal architect of its downfall in India. At the same time, he has been described as a Buddhist in disguise. Both these opinions have been expressed by ancient as well as modern authors—scholars, philosophers, historians, and sectaries."

- Edward Roer (Translator), to Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad at pages 3–4Shankara's Introduction, p. 3, at Google Books

- Edward Roer (Translator), Shankara's Introduction, p. 3, at Google Books to Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad at page 3, OCLC 19373677

- KN Jayatilleke (2010), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge, ISBN 978-81-208-0619-1, pages 246–249, from note 385 onwards

- Steven Collins (1994), Religion and Practical Reason (Editors: Frank Reynolds, David Tracy), State Univ of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2217-5, page 64; Quote: "Central to Buddhist soteriology is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the [Buddhist] doctrine that human beings have no soul, no self, no unchanging essence."

- Edward Roer (Translator), Shankara's Introduction, p. 2, at Google Books, pages 2–4

Katie Javanaud (2013), Is The Buddhist 'No-Self' Doctrine Compatible With Pursuing Nirvana?, Philosophy Now - John C. Plott et al. (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Axial Age, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0158-5, page 63, Quote: "The Buddhist schools reject any Ātman concept. As we have already observed, this is the basic and ineradicable distinction between Hinduism and Buddhism".

- Harvey, Peter, Introduction to Buddhism, p. 195.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 153.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 156, 163.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 162.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 156, 168.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 235.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 238-241.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 244.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes, Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism BRILL, 2011, p. 245.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, pages 180, 182.

- Hajime Nakamura (1980). Indian Buddhism: A Survey with Bibliographical Notes. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 145–148 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-0272-8.

- Akira Shimada (2012). Early Buddhist Architecture in Context: The Great Stūpa at Amarāvatī (ca. 300 BCE-300 CE). BRILL Academic. pp. 200–204. ISBN 978-90-04-23326-3.

- Gregory Schopen (1997). Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks: Collected Papers on the Archaeology, Epigraphy, and Texts of Monastic Buddhism in India. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 259–278. ISBN 978-0-8248-1870-8.

- Gina Barns (1995). "An Introduction to Buddhist Archaeology". World Archaeology. 27 (2): 166–168. doi:10.1080/00438243.1995.9980301.

- Lars Fogelin (2015). An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-19-994823-9.

- Sanyal, Sanjeev (15 November 2012). Land of seven rivers: History of India's Geography. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 130–1. ISBN 978-81-8475-671-5.

- Peter Harvey (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4.

- Levy, Robert I. Mesocosm: Hinduism and the Organization of a Traditional Newar City in Nepal. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990.

- Muhammad ibn Ahmad Biruni; Edward C. Sachau (Translator) (1888). Alberuni's India: An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India about AD 1030. Cambridge University Press. pp. 253–254. ISBN 978-1-108-04720-3.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Historical Development of Buddhism in India - Buddhism under the Guptas and Palas". Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- McLeod, John, "The History of India", Greenwood Press (2002), ISBN 0-313-31459-4, pg. 41-42.

- Powers, John (5 October 2015). The Buddhist World. ISBN 9781317420170.

- Chap. XXVII-XLIV, Synopsis by Nalinaksha Dutt, Accounts of Pala, Sena kings, Vikramshila, Turushkas and status of Buddhism in India, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia

- William M. Johnston (2000). Encyclopedia of Monasticism: A-L. Routledge. p. 335. ISBN 978-1-57958-090-2.

- Eraly, Abraham (April 2015). The Age of Wrath: A History of the Delhi Sultanate. ISBN 9789351186588.

- A Comprehensive History Of India, Vol. 4, Part 1, page 600 & 601

- Historia Religionum: Handbook for the History of Religions By C. J. Bleeker, G. Widengren page 381

- P. 41 Where the Buddha Walked by S. Muthiah

- Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In: Genesis and Development of Tantrism, edited by Shingo Einoo. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23, pp. 89.

- Islam at War: A History By Mark W. Walton, George F. Nafziger, Laurent W. Mbanda (page 226)

- Roerich, G. 1959. Biography of Dharmasvamin (Chag lo tsa-ba Chos-rje-dpal): A Tibetan Monk Pilgrim. Patna: K. P. Jayaswal Research Institute. pg. 61–62, 64, 98.

- Fogelin, Lars, An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism, Oxford University Press, p. 222.

- André Wink (1997). Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World. BRILL Academic. pp. 348–349. ISBN 90-04-10236-1.

- Alexis Sanderson (2009). "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period". In Einoo, Shingo (ed.). Genesis and Development of Tantrism. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo. p. 89.

- Randall COLLINS (2009). THE SOCIOLOGY OF PHILOSOPHIES. Harvard University Press. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-0-674-02977-4.

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1951). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The struggle for empire. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 426.

- Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, pages 184-185

- Craig Lockard (2007). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: Volume I: A Global History. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 364. ISBN 978-0-618-38612-3.

- Peter Harvey (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4.

- André Wink (1997). Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World. BRILL Academic. ISBN 90-04-10236-1.

- Lars Fogelin (2015). An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford University Press. pp. 223–224. ISBN 9780199948222.

- Harvey, Peter, Introduction to Buddhism, p. 196.

- Fogelin, Lars, An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism, Oxford University Press, p. 224.

- Contemporary Buddhism in Bangladesh By Sukomal Chaudhuri

- P. 180 Indological Studies By Bimala Churn Law

- Middle Land, Middle Way: A Pilgrim's Guide to the Buddha's India, Shravasti Dhammika, Buddhist Publication Society, 1992p. 55-56

- Kishori Saran Lal (1999). Theory and Practice of Muslim State in India. Aditya Prakashan. p. 110.

- Irfan Habib (1997). Akbar and His India. Oxford University Press. p. 98.

- Tharanatha; Chattopadhyaya, Chimpa, Alaka, trans. (2000). History of Buddhism in India, Motilal Books UK, p. 333-338 ISBN 8120806964.

- Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Devraj to Jyoti, Volume 2, Amaresh Datta, Jain Literature (Marathi), Sahitya Akademi, 1988 p. 1779

- Shodha Tippana, Pro. Vidyadhar Joharapurkar, in Anekanta, June 1963, pp. 73-75.

- No. 7.-DISTRIBUTION of POPULATION according to RELIGION (CENSUS of 1901), South Asia Library, University of Chicago

- No. 7.-Distribution of Population according to Religion (Census of 1911), South Asia Library, University of Chicago

- Achary Tsultsem Gyatso; Mullard, Saul & Tsewang Paljor (Transl.): A Short Biography of Four Tibetan Lamas and Their Activities in Sikkim, in: Bulletin of Tibetology Nr. 49, 2/2005, p. 57.

- Christopher S. Queen; Sallie B. King (1996). Engaged Buddhism: Buddhist Liberation Movements in Asia. State University of New York Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-7914-2844-3.

- Pritchett, Frances (2 August 2006). "Columbia University" (PHP). Retrieved 2 August 2006.

- Maren Bellwinkel-Schempp (2004). "Roots of Ambedkar Buddhism in Kanpur" (PDF).

- The Dalai Lama: A Policy of Kindness By Sidney Piburn (page 12)

- Chris Park (2002). Sacred Worlds: An Introduction to Geography and Religion. Routledge. pp. 66–68. ISBN 978-1-134-87735-5.

Sources

- Anand, Ashok Kumar (1996), "Buddhism in India", Gyan Books, ISBN 978-81-212-0506-1

- Berkwitz, Stephen C. (2012), South Asian Buddhism: A Survey, Routledge

- Bhagwan, Das (1988), Revival of Buddhism in India and Role of Dr. Baba Saheb B.R. Ambedkar, Dalit Today Prakashan, Lucknow -226016, India. ISBN 8187558016

- Dhammika, S. (1993). The Edicts of King Ashoka (PDF). Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 978-955-24-0104-6. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Doniger, Wendy (2000). Merriam-Webster Encyclopedia of World Religions. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 1378. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- Elverskog, Johan (2011), Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0812205312

- Inden, Ronald B. (2000), Imagining India, C. Hurst & Co. PublishersCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Michaels, Axel (2004), Hinduism. Past and present, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University PressCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charles (EDT) Willemen, Bart Dessein, Collett Cox, "Sarvastivada Buddhist Scholasticism", 1998, Brill Academic Publishers

- White, David Gordon (2012), The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India, University of Chicago Press

- Wink, André (2004), "Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World", BRILL, ISBN 90-04-10236-1

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent |

- Archaeology and Protestant Presuppositions in the Study of Indian Buddhism, Gregory Schopen (1991), History of Religions

- Commerce and Culture in South Asia: Perspectives from Archaeology and History, Kathleen D. Morrison (1997), Annual Reviews