Syriac Christianity

Syriac Christianity (Syriac: ܡܫܝܚܝܘܬܐ ܣܘܪܝܝܬܐ / Mšiḥāyuṯā Suryāyṯā; Arabic: مسيحية سريانية, masīḥīat surīānīa) is the form of Eastern Christianity whose formative theological writings and traditional liturgy are expressed in the Syriac language,[1][2][3] which, along with Latin and Greek, was one of "the three most important Christian languages in the early centuries" of the Common Era.[4]

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

|

Main communions

|

|

Eastern liturgical rites |

|

Syriac Christianity comprises two liturgical traditions. The East Syriac Rite (also known as the Chaldean, Assyrian, or Persian Rite),[5] whose main anaphora is the Holy Qurbana of Saints Addai and Mari, is that of the Iraq-based Chaldean Catholic Church, Assyrian Church of the East and Ancient Church of the East, and the Indian Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and Chaldean Syrian Church (the latter being part of the Assyrian Church of the East). The West Syriac Rite, which has the Divine Liturgy of Saint James as its anaphora, is that of the Syria-based Syriac Orthodox Church, the Lebanon-based Maronite Church and Syriac Catholic Church, and the Indian Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, Jacobite Syrian Christian Church (part of the Syriac Orthodox Church), Malabar Independent Syrian Church. Modified (Anglican-influenced) version of this rite are used by the Reformed Eastern Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church[6][7][8] and the more strongly Protestant St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India.

In India, Christians of both traditions are called Syrian Christians and Saint Thomas Christians.[9] Two such Indian churches, the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church are in communion with the See of Rome. The Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church is in the Oriental Orthodox communion, to which the Syriac Orthodox Church (of which the Jacobite Syrian Christian Church is part) also belongs. The Malabar Independent Syrian Church, an independent Oriental Orthodox church, that is not part of the Oriental Orthodox Communion. The Mar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar is linked in full communion with the Anglican Communion. The Chaldean Syrian Church is part of the Assyrian Church of the East.

The Syriac language is a variety of Middle Aramaic that in an early form emerged in Edessa, Upper Mesopotamia in the first century AD.[10] It is closely related to the Aramaic of Jesus, a Galilean dialect.[11] This relationship added to its prestige for Christians.[12] The form of the language in use in Edessa predominated Christian writings and was accepted as the standard form, "a convenient vehicle for the spread of Christianity wherever there was a substrate of spoken Aramaic".[1] The area where Syriac or Aramaic was spoken, an area of contact and conflict between the Roman Empire and the Sasanian Empire, extended from around Antioch in the west to Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Sasanian capital (in Iraq), in the east[1] and comprised the whole or parts of present-day Lebanon, Palestine/Israel, Syria, Turkey, Iraq and Iran.[2]

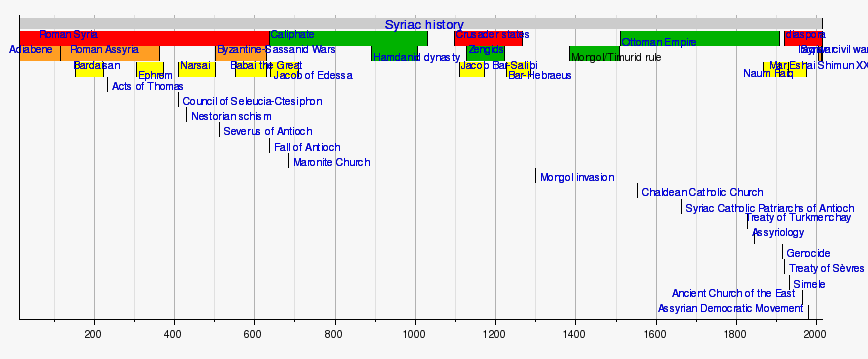

History

Christianity began in the Middle East in Jerusalem among Aramaic-speaking Jews. It soon spread to other Aramaic-speaking Semitic peoples along the Mediterranean coast and also to the inland parts of the Roman Empire and beyond that into the Parthian Empire and the later Sasanian Empire, including Mesopotamia, which was dominated at different times and to varying extents by these empires.

The ruins of the Dura-Europos church, dating from the first half of the 3rd century are concrete evidence of the presence of organized Christian communities in the Aramaic-speaking area, far from Jerusalem and the Mediterranean coast, and there are traditions of the preaching of Christianity in the region as early as the time of the Apostles.

However, "virtually every aspect of Syriac Christianity prior to the fourth century remains obscure, and it is only then that one can feel oneself on firmer ground."[13] The fourth century is marked by the many writings in Syriac of Saint Ephrem the Syrian, the Demonstrations of the slightly older Aphrahat and the anonymous ascetical Book of Steps. Ephrem lived in the Roman Empire, close to the border with the Sasanian Empire, to which the other two writers belonged.[13]

Other items of early literature of Syriac Christianity are the Diatessaron of Tatian, the Curetonian Gospels and the Syriac Sinaiticus, the Peshitta Bible and the Doctrine of Addai.

The bishops who took part in the First Council of Nicea (325), the first of the ecumenical councils, included twenty from Syria and one from Persia, outside the Roman Empire.[14] Two councils held in the following century divided Syriac Christianity into two opposing parties.

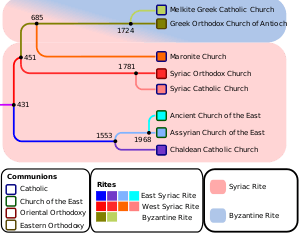

East-West theological contrast

In 431, the Council of Ephesus, which is reckoned as the third ecumenical council, condemned Nestorius and Nestorianism. It was ignored by the East Syriac Church of the East, which had been established in the Sasanian Empire as a distinct Church at the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410, and which at the Synod of Dadisho in 424 had declared the independence of its head, the Catholicos, in relation to "western" (Roman Empire) Church authorities. Even in its modern form of Assyrian Church of the East and Ancient Church of the East, it honours Nestorius as a teacher and saint.[15]

In 451, the Council of Chalcedon, the fourth ecumenical council, condemned Monophysitism. This council was rejected by the Oriental Orthodox Churches, one of which is the West Syriac Syriac Orthodox Church. The Patriarchate of Antioch was then divided between a Chalcedonian and a non-Chalcedonian communion. The Chalcedonians were often labelled 'Melkites' (Emperor's Party), while their opponents were labelled Monophysites (those who believe in the one rather than two natures of Christ) and Jacobites (after Jacob Baradaeus). The Maronite Church found itself caught between the two (allegedly embracing Monothelitism), but claims to have always remained faithful to the Catholic Church and in communion with the bishop of Rome, the Pope.[16]

The two Christological doctrines that were thus condemned are polar opposites.[17] Both the West Syriac Church and the East Syriac maintained that their own doctrine was not heretical and accused the other of holding the opposing condemned doctrine.

Their fifth-century estrangement still persists. In 1999 the Coptic Orthodox Church blocked admittance of the Assyrian Church of the East to the Middle East Council of Churches, which has among its members the Chaldean Catholic Church,[18] [19] and demanded that it remove from its liturgy the mention of Diodore, Theodore, and Nestorius, whom it venerates as "the Greek doctors".[20]

East-West liturgical contrast

The liturgies of the East and West Syriacs are quite distinct. The East Syriac Rite is noted especially for its eucharistic Qurbana of Addai and Mari, in which the Words of Institution are absent. West Syriacs use the Syro-Antiochian or West Syriac Rite, which belongs to the family of liturgies known as the Antiochene Rite.

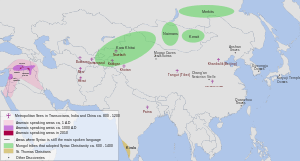

The Syriac Orthodox Church adds to the Trisagion ("Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us") the phrase "who were crucified for us". The Church of the East interpreted this as heretical.[21] Church of the East Patriarch Timothy I declared: "In all countries of Babylon, of Persia, and of Assyria and in all countries of sunrise, that is to say among the Indians, the Chinese, the Tibetans, the Turks, and in all provinces under the jurisdiction of this Patriarchal See there is no use of 'Crucified for us'.”[22]

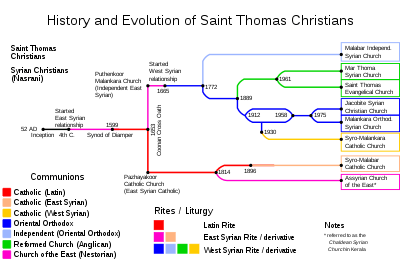

Among the Saint Thomas Christians of India, the East Syriac Rite was the one originally used, but those who in the 17th century accepted union with the Syriac Orthodox Church adopted the rite of that church.

Further divisions

A schism in 1552 in the Church of the East gave rise to a separate patriarchate, which at first entered into union with the Catholic Church but later formed the nucleus of the present-day Assyrian Church of the East and Ancient Church of the East, while at the end of the 18th century most followers of the earlier patriarchate chose union with Rome and, with some others, now form the Chaldean Catholic Church.

In India, the majority of the Saint Thomas Christians, who initially depended on the Church of the East, maintained union with Rome in spite of discomforts felt at Latinizations by their Portuguese rulers and clergy, against which they protested. They now form the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church. A small group, which split from these in the early 19th century, united at the beginning of the 20th century, under the name of Chaldean Syrian Church, with the Assyrian Church of the East.

In India, all the Saint Thomas Christians are collectively called Syrian Christians.

Those who in 1553 broke with the Catholic Church as dominated by the Portuguese in India and soon chose union with the Syriac Orthodox Church later split into various groups. The first separation was that of the Malabar Independent Syrian Church in 1772.[23] At the end of the 19th century and in the course of the 20th, a division arose among those who remained united with the Syriac Orthodox Church who insisted on full autocephaly and are now called the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church and those, the Jacobite Syrian Christian Church, who remain faithful to the patriarch.

A reunion movement led in 1930 to the establishment of full communion between some of the Malankara Syrian Orthodox and the Catholic Church. They now form the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

In the Middle East, the newly enthroned patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church, Ignatius Michael III Jarweh, declared himself a Catholic and, having received confirmation from Rome in 1783, became the head of the Syriac Catholic Church.

In the 19th and 20th centuries many Syriac Christians, both East ad West, left the Middle East for other lands, creating a substantial diaspora.[24]

Names

Indigenous Aramaic speakers of Mesopotamia (Syriac: ܣܘܪܝܝܐ, Arabic: سُريان)[25] adopted Christianity very early, perhaps already from the first century, and began to abandon their three-millennia-old traditional ancient Mesopotamian religion, although this religion did not fully die out until as late as the tenth century. The kingdom of Osroene with the city of Edessa was absorbed into the Roman Empire in 114 as a semiautonomous vassal state and then, after a period under the rule of the Parthian Empire, was incorporated as a simple Roman province in 214.[26][27]

In 431 the Council of Ephesus declared Nestorianism a heresy. Nestorians, persecuted in the Byzantine Empire, sought refuge in the parts of Mesopotamia that were part of the Sasanian Empire. This encouraged acceptance of Nestorian doctrine by the Persian Church of the East, which spread Christianity outside Persia, to India, China, Tibet and Mongolia, expanding the range of this eastern branch of Syriac Christianity. The western branch, the Jacobite Church, appeared after the Council of Chalcedon's condemnation of Monophysitism in 451.[28]

Churches of Syriac traditions

- West Syriac Rite

- Oriental Orthodox

- The Syriac Orthodox Church (Non-Chalcedonian Oriental Orthodox Church of Antioch and all the East)

- The Jacobite Syrian Christian Church; (Non-Chalcedonian Oriental Orthodox Church of India within the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate)

- The Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church(Syrian Church based in Kerala) (Autocephalous; Non-Chalcedonian Oriental Orthodox Church of India) with her part the Brahmavar (Goan) Orthodox Church

- The Malabar Independent Syrian Church (Thozhiyur church), an independent oriental orthodox church based in Kerala, India.

- Eastern Catholic Churches with the West Syriac Rite.

- The Syriac Catholic Church.

- The Syriac Maronite Church.

- The Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, (Syrian Catholic Church based in Kerala, India.)

- The Mar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar, linked in full communion with the Anglican Communion.

- The St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India, of Evangelical-style theology.

- Oriental Orthodox

- East Syriac Rite and non-Ephesian tradition

- Church of the East, founded in the Sasanian Empire, became known as the Nestorian Church, once widespread throughout Asia

- The Assyrian Church of the East, traditionalist continuation of the Church of the East that took this name in 1976

- The Chaldean Syrian Church an archbishopric in India of the Assyrian Church of the East

- The Ancient Church of the East, split from the Assyrian Church of the East in the 1960s

- The Assyrian Church of the East, traditionalist continuation of the Church of the East that took this name in 1976

- The East Syriac Rite Churches within the Catholic Church

- The Chaldean Catholic Church, an Eastern Catholic Church that emerged from the Church of the East following splits in 1552, 1667/1668 and 1779

- The Syro(Syrian) Malabar Catholic Church.(Syrian Catholic Church based in Kerala).

- Church of the East, founded in the Sasanian Empire, became known as the Nestorian Church, once widespread throughout Asia

East Syriac Christians were involved in the mission to India, and many of the present Churches in India are in communion with either East or West Syriac Churches. These Indian Christians are known as Saint Thomas Christians.

In modern times, even apart from the Reformed Eastern Mar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar and St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India, which originated from West Syriac Rite Churches,[6] various Evangelical denominations sent representatives among the Syriac peoples. As a result, several Evangelical groups have been established, particularly the Assyrian Pentecostal Church (mostly in America, Iran, and Iraq) from East Syriac peoples, and the Aramean Free Church (mostly in Germany, Sweden, America and Syria) from West Syriac peoples. Because of their Protestant theology these are not normally classified as Eastern Churches or Syriac Christianity.

See also

References

Citations

- Lucas van Rompay, "The East: Syria and Mesopotamia" in Susan Ashbrook Harvey, David G. Hunter (editors), The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Studies (Oxford University Press 2008), p. 366

- Heleen Murre-van der Berg, "Syriac Christianity" in Ken Parry (editor), The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity (John Wiley & Sons 2010), p. 249

- Robert A. Kitchen, "The Syriac Tradition" in Augustine Casiday, The Orthodox Christian World (Routledge 2012), p. 66

- Wilken, Robert Louis (2012-11-27). The First Thousand Years: A Global History of Christianity. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-300-11884-1.

- John Hardon (25 June 2013). Catholic Dictionary: An Abridged and Updated Edition of Modern Catholic Dictionary. Crown Publishing Group. p. 493. ISBN 978-0-307-88635-4.

- Pallikunnil, Jameson K. (2017). The Eucharistic Liturgy: A Liturgical Foundation for Mission in the Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church. ISBN 978-1-5246-7652-0.

Metropolitan Juhanon Mar Thoma called it “a Protestant Church in an oriental garb”. As a reformed Oriental Church, it agrees with the reformed doctrines of the Western churches. Therefore, there is much in common in faith and doctrine between the MTC and the reformed Churches of the West. As the Church now sees it, just as the Anglican church is a Western Reformed Church, the MTC is an Eastern Reformed Church..

- World Council of Churches, "Mar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar"

- Ed Hindson, Dan Mitchell (editors), The Popular Encyclopedia of Church History (Harvest House Publishers, 2013), p. 225

- Abraham Vazhayil Thomas, Christians in Secular India (Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1974), p. 90

- Cameron, Averil; Garnsey, Peter (1998). The Cambridge Ancient History. 13. p. 708. ISBN 9780521302005.

- Allen C. Myers, ed (1987). "Aramaic". The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. p. 72. ISBN 0-8028-2402-1. "It is generally agreed that Aramaic was the common language of Palestine in the first century A.D. Jesus and his disciples spoke the Galilean dialect, which was distinguished from that of Jerusalem (Matt. 26:73)."

- Robert L. Montgomery, The Lopsided Spread of Christianity: Toward an Understanding of the Diffusion of Religions (Greenwood Publishing Group 2002), p. 27

- Sebastian P. Brock, "Ephrem and the Syriac Tradition" in Frances Young, Lewis Ayres, Andrew Louth (editors), The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature (Cambridge University Press 2004), Volume 1, p. 362

- Montgomery (2002), pp. 27, 57

- Wilhelm Baum and Dietmar W. Winkler, The Church of the East: A concise history (Routledge 2003), pp. 5, 30

- Moosa, Matti. The Maronites in history. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1986

- Brian Albert Gerrish, Faith: Dogmatics in Outline (Presbyterian Publishing Corp 2015), p. 152

- Wilhelm Baum and Dietmar W. Winkler, The Church of the East: A concise history (Routledge 2003), pp. 151−152

- Aidan Nichols, Rome and the Eastern Churches: A Study in Schism (Ignatius Press 2010), footnote 98

- Metropolitan Bishoy, "The Assyrian Churches"

- Marijke Metselaar-Jongens, Defining Christ: The Church of the East and Nascent Islam (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam 2016), p. 79

- B.M. Thomas, "The St Thomas Christians and their East Syrian Connection: Sources and conclusions" (Federated Faculty for Research in Religion and Culture, Kottayam 2015), p. 3

- Fenwick, John R. K. "Malabar Independent Syrian Church The Thozhiyur Church".

- Chaillot, Christine. "The Syrian Orthodox Church Of Antioch And All The East. Geneva: Inter-Orthodox Dialogue 1998

- Donabed, Sargon (2015). Reforging a Forgotten History: Iraq and the Assyrians in the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7486-8605-6.

- Steven K. Ross, Roman Edessa: Politics and Culture on the Eastern Fringes of the Roman Empire, 114 - 242 C.E. (Routledge c2000), p. 49

- Adrian Fortescue, The Lesser Eastern Churches (Catholic Truth Society 1913), p. 23

- T.V. Philip, East of the Euphrates: Early Christianity in Asia

Sources

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon. ISBN 9781134430192.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1992). Studies in Syriac Christianity: History, Literature, and Theology. Aldershot: Variorum. ISBN 9780860783053.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1996). Syriac Studies: A Classified Bibliography, 1960-1990. Kaslik: Parole de l'Orient.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1997). A Brief Outline of Syriac Literature. Kottayam: St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006). Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754659082.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chabot, Jean-Baptiste (1902). Synodicon orientale ou recueil de synodes nestoriens (PDF). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in historyb. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410556.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seleznyov, Nikolai N. (2010). "Nestorius of Constantinople: Condemnation, Suppression, Veneration: With special reference to the role of his name in East-Syriac Christianity". Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. 62 (3–4): 165–190.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Jacobite Syrian Church

- (in French) – Translation into English Syriac Christianity on WikiSyr

- (in French) – Translation into English Syriac Catholic Circle

- Qambel Maran- Syriac chants from South India- a review and liturgical music tradition of Syriac Christians revisited

- Traditions and rituals among the Syrian Christians of Kerala

- Audio Aramaic-Bible

- The Center for the Study of Christianity: A Comprehensive Bibliography on Syriac Christianity