Linguistic discrimination

Linguistic discrimination (also called glottophobia, linguicism and languagism) is unfair treatment which is based on use of language and characteristics of speech, including first language, accent, size of vocabulary (whether the speaker uses complex and varied words), modality, and syntax. For example, an Occitan-speaker in France will probably be treated differently from a French-speaker.[1] Based on a difference in use of language, a person may automatically form judgments about another person's wealth, education, social status, character or other traits, which may lead to discrimination.

In the mid-1980s, linguist Tove Skutnabb-Kangas, captured the idea of language-based discrimination as linguicism, which was defined as "ideologies and structures which are used to legitimate, effectuate, and reproduce unequal division of power and resources (both material and non-material) between groups which are defined on the basis of language".[2] Although different names have been given to this form of discrimination, they all hold the same definition. It is also important to note that linguistic discrimination is culturally and socially determined due to preference for one use of language over others.

Carolyn McKinley[3] is critical of a dominant language because it does not only discriminate against speakers of other languages, it also disadvantages monolinguals because they remain monolingual.[4] Instead of using the indigenous languages along with the colonial languages, as McKinley also advocates, most African states still use the colonial language as the main medium of instruction.[4] Furthermore, in authoritative reports by Unesco, it was found that the use of the former colonial languages in Africa benefited only the elite and disadvantaged the bulk of the populations.[4] Although English has worldwide meaning as a language of discourse, it is not neutral as it leads too much to a culture-dependent perspective in thinking and talking by the use of culturally bound value concepts, often blind value judgments and frames of reference inherent to and shaped by English culture, according to Anna Wierzbicka.[3]

Linguistic prejudice

It can be noted that speakers with certain accents may experience prejudice. For example, some accents hold more prestige than others depending on the cultural context. However, with so many dialects, it can be difficult to determine which is the most preferable. The best answer linguists can give, such as the authors of "Do You Speak American?", is that it depends on the location and the speaker. Research has determined however that some sounds in languages may be determined to sound less pleasant naturally.[5] Also, certain accents tend to carry more prestige in some societies over other accents. For example, in the United States speaking General American (i.e., an absence of a regional, ethnic, or working class accent) is widely preferred in many contexts such as television journalism. Also, in the United Kingdom, the Received Pronunciation is associated with being of higher class and thus more likeable.[6] In addition to prestige, research has shown that certain accents may also be associated with less intelligence, and having poorer social skills.[7] An example can be seen in the difference between Southerners and Northerners in the United States, where people from the North are typically perceived as being less likable in character, and Southerners are perceived as being less intelligent. As sociolinguist, Lippi-Green, argues, "It has been widely observed that when histories are written, they focus on the dominant class... Generally studies of the development of language over time are very narrowly focused on the smallest portion of speakers: those with power and resources to control the distribution of information." [8]

Language and social group saliency

.jpg)

It is natural for human beings to want to identify with others. One way we do this is by categorizing individuals into specific social groups. While some groups may be readily noticeable (such as those defined by ethnicity or gender), other groups are less salient. Linguist Carmen Fought explains how an individual's use of language may allow another person to categorize them into a specific social group that may otherwise be less apparent. For example, in the United States it is common to perceive Southerners as less intelligent. Belonging to a social group such as the South may be less salient than membership to other groups that are defined by ethnicity or gender. Language provides a bridge for prejudice to occur for these less salient social groups.[9]

Linguistic discrimination and colonization

History of linguistic imperialism

The impacts of colonization on linguistic traditions vary based on the form of colonization experienced: trader, settler or exploitation.[10] Congolese-American linguist Salikoko Mufwene describes trader colonization as one of the earliest forms of European colonization. In regions such as the western coast of Africa as well as the Americas, trade relations between European colonizers and indigenous peoples led to the development of pidgin languages.[10] Some of these languages, such as Delaware Pidgin and Mobilian Jargon, were based on Native American languages, while others, such as Nigerian Pidgin and Cameroonian Pidgin, were based on European ones.[11] As trader colonization proceeded mainly via these hybrid languages, rather than the languages of the colonizers, scholars like Mufwene contend that it posed little threat to indigenous languages.[11]

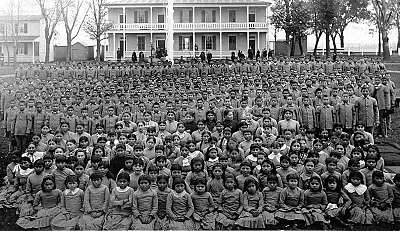

Trader colonization was often followed by settler colonization, where European colonizers settled in these colonies to build new homes.[10] Hamel, a Mexican linguist, argues that "segregation" and "integration" were two primary ways through which settler colonists engaged with aboriginal cultures.[12] In countries such as Uruguay, Brazil, Argentina, and those in the Caribbean, segregation and genocide decimated indigenous societies.[12] Widespread death due to war and illness caused many indigenous populations to lose their indigenous languages.[10] In contrast, in countries that pursued policies of "integration", such as Mexico, Guatemala and the Andean states, indigenous cultures were lost as aboriginal tribes mixed with colonists.[12] In these countries, the establishment of new European orders led to the adoption of colonial languages in governance and industry.[10] In addition, European colonists also viewed the dissolution of indigenous societies and traditions as necessary for the development of a unified nation state.[12] This led to efforts to destroy tribal languages and cultures: in Canada and the United States, for example, Native children were sent to boarding schools such as Col. Richard Pratt's Carlisle Indian Industrial School.[10][13] Today, in countries such as the United States and Australia, which were once settler colonies, indigenous languages are spoken by only a small minority of the populace.

Mufwene also makes a distinction between settler colonies and exploitation colonies. In the latter, the colonization process was focused on the extraction of raw materials needed in Europe.[10] As a result, Europeans were less invested in their exploitation colonies, and few colonists planned to build homes in these colonies. As a result, indigenous languages were able to survive to a greater extent in these colonies compared to settler colonies.[10] In exploitation colonies, colonial languages were often only taught to a small local elite. During the British Raj, for example, Lord Macaulay highlighted the need for “… a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions who govern… a class of persons, Indian in blood and color, but English in taste, in my opinion, in morals and in intellect” in his now-famous “Macaulay minutes”, which were written in support of the English Education Act of 1835.[14] The linguistic differences between the local elite and other locals exacerbated class stratification, and also increased inequality in access to education, industry and civic society in postcolonial states.[10]

Linguistic discrimination and culture

Several postcolonial literary theorists have drawn a link between linguistic discrimination and the oppression of indigenous cultures. Prominent Kenyan author Ngugi wa Thiong'o, for example, argues in his book "Decolonizing the Mind" that language is both a medium of communication, as well as a carrier of culture.[15] As a result, linguistic discrimination resulting from colonization has facilitated the erasure of pre-colonial histories and identities.[15] For example, African slaves were taught English and forbidden to use their indigenous languages. This severed the slaves' linguistic and thus cultural connection to Africa.[15]

Colonial languages and class

In contrast to settler colonies, in exploitation colonies, education in colonial tongues was only accessible to a small indigenous elite.[11] Both the British Macaulay Doctrine, as well as French and Portuguese systems of assimilation, for example, sought to create an "elite class of colonial auxiliaries" who could serve as intermediaries between the colonists and local populace.[11] As a result, fluency in colonial languages became a signifier of class in colonized lands.

In postcolonial states, linguistic discrimination continues to reinforce notions of class. In Haiti, for example, working-class Haitians predominantly speak Haitian Creole, while members of the local bourgeoise are able to speak both French and Creole.[16] Members of this local elite frequently conduct business and politics in French, thereby excluding many of the working-class from such activities.[16] In addition, D. L. Sheath, an advocate for the use of indigenous languages in India, also writes that the Indian elite associates nationalism with a unitary identity, and in this context, "uses English as a means of exclusion and an instrument of cultural hegemony”.[14]

Linguistic discrimination in education

.jpg)

Class disparities in postcolonial nations are often reproduced through education. In countries such as Haiti, schools attended by the bourgeoisie are usually of higher quality and use colonial languages as their means of instruction. On the other hand, schools attended by the rest of the population are often taught in Haitian Creole.[16] Scholars such as Hebblethwaite argue that Creole-based education will improve learning, literacy and socioeconomic mobility in a country where 95% of the population are monolingual in Creole.[17] However, resultant disparities in colonial language fluency and educational quality can impede social mobility.[16]

On the other hand, areas such as French Guiana have chosen to teach colonial languages in all schools, often to the exclusion of local indigenous languages.[18] As colonial languages were viewed by many as the “civilized” tongues, being “educated” often meant being able to speak and write in these colonial tongues.[18] Indigenous language education was often seen as an impediment to achieving fluency in these colonial languages, and thus deliberately suppressed.[18]

.jpg)

Certain British colonies such as Uganda and Kenya have historically had a policy of teaching in indigenous languages and only introducing English in the upper grades.[19] This policy was a legacy of the "dual mandate" as conceived by Lord Lugate, a prominent British administrator in colonial Africa.[19] However, by the post-war period, English was increasingly viewed as necessary skill for accessing professional employment and better economic opportunities.[19][20] As a result, there was increasing support amongst the populace for English-based education, which Kenya's Ministry of Education adopted post-independence, and Uganda following their civil war. Later on, members of the Ominde Commission in Kenya expressed the need for Kiswahili in promoting a national and pan-African identity. Kenya therefore began to offer Kiswahili as a compulsory, non-examinable subject in primary school, but it remained secondary to English as a medium of instruction.[19]

While the mastery of colonial languages may provide better economic opportunities, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child also states that minority children have the right to “use [their] own [languages]”. The suppression of indigenous languages within the education system appears to contravene this treaty.[21][22] In addition, children who speak indigenous languages can also be disadvantaged when educated in foreign languages, and often have high illiteracy rates. For example, when the French arrived to “civilize” Algeria, which included imposing French on local Algerians, the literacy rate in Algeria was over 40%, higher than that in France at the time. However, when the French left in 1962, the literacy rate in Algiers was at best 10-15%.[23]

Linguistic discrimination in governance

As colonial languages are used as the languages of governance and commerce in many colonial and postcolonial states,[10] locals who only speak indigenous languages can be disenfranchised. For example, when representative institutions were introduced to the Algoma region in what is now modern-day Canada, the local returning officer only accepted the votes of individuals who were enfranchised, which required indigenous peoples to "read and write fluently... [their] own and another language, either English or French".[24] This caused political parties to increasingly identify with settler perspectives rather than indigenous ones.[24]

Even today, many postcolonial states continue to use colonial languages in their public institutions, even though these languages are not spoken by the majority of their residents.[25] For example, the South African justice system still relies primarily on English and Afrikaans as its primary languages, even though most South Africans speak indigenous languages.[26] In these situations, the use of colonial languages can present barriers to participation in public institutions.

Examples

Linguistic discrimination is often defined in terms of prejudice of language. It is important to note that although there is a relationship between prejudice and discrimination, they are not always directly related.[27] Prejudice can be defined as negative attitudes towards a person based on their membership of a social group, whereas discrimination can be seen as the acts towards them. The difference between the two should be recognized because prejudice may be held against someone, but it may not be acted on.[28] The following are examples of linguistic prejudice which may result in discrimination.

Linguistic prejudice and minority groups

While, theoretically, any speaker may be the victim of linguicism regardless of social and ethnic status, oppressed and marginalized social minorities are often the most consistent targets, due to the fact that the speech varieties that come to be associated with such groups have a tendency to be stigmatized.

In Canada

French communities in Quebec, New Brunswick, Ontario and the Red River Rebellion

The Canadian federation and provinces have historically discriminated against their French-speaking population in favor of the financially powerful English-speaking population.

Quebec's English community

The Charter of the French Language, first established in 1977 and amended several times since, has been accused of being discriminatory by English-speakers. The law makes French the official language of Quebec and mandates its use (with exceptions) in government offices and communiques, schools, and in commercial public relations. Though the English-speaking population had been shrinking since the 1960s, it was hastened by the law, and the 2006 census showed a net loss of 180,000 native English-speakers.[29]

Conversely, the law has been seen as a way of preventing linguistic discrimination against French speakers, as part of the law's wider goal to protect French against the growing social and economic dominance of English. Speaking English at work continues to be strongly correlated with higher earnings, with French-only speakers earning significantly less.[30] Despite this, the law is widely credited with successfully raising the status of French in a predominantly English-speaking economy, and it has been influential in countries facing similar circumstances.[29]

In Europe

Linguistic disenfranchisement rate

The linguistic disenfranchisement rate in the EU can significantly vary across countries. For residents in two EU-countries that are either native speakers of English or proficient in English as a foreign language the disenfranchisement rate is equal to zero. In his study "Multilingual communication for whom? Language policy and fairness in the European Union" Michele Gazzola comes to the conclusion that the current multilingual policy of the EU is not in the absolute the most effective way to inform Europeans about the EU; in certain countries, additional languages may be useful to minimize linguistic exclusion.[31]

In the 24 countries examined, an English-only language policy would exclude 51% to 90% of adult residents. A language regime based on English, French and German would disenfranchise 30% to 56% of residents, whereas a regime based on six languages would bring the shares of excluded population down to 9–22%. After Brexit, the rates of linguistic exclusion associated with a monolingual policy and with a trilingual and a hexalingual regime are likely to increase.[31]

Language policy of the British Empire in Ireland, Wales and Scotland

- Cromwell's conquest, the long English colonisation and Great Irish Famine made Irish a minority language by the end of the 19th century. It had no official status until the establishment of Republic of Ireland.

- In Wales, it was forbidden to speak Welsh in schools.

- Scottish Gaelic also had no official status until 2005; it was banned from the educational system because it was "one of the chief, principal causes of barbarity and incivility" in the words of one statute.[32]

- Scots was in 1946 not considered "a suitable medium of education or culture".[33]

Other examples

- Basque: public usage of Basque was restricted in Spain under Franco, 1939 to 1965. Galician and Catalan have similar histories.

- Vergonha is the term used for the effect of various policies of the French government on its citizens whose mother tongue was one of so-called patois. In 1539, with Article 111 of the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, French (the language of Ile-de-France) became the only official language in the country despite being spoken by only a minority of the population. In education and administration, it was forbidden to use regional languages, such as Occitan, Catalan, Basque and Breton. The French government still has not ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

- Magyarisation in the 19th-century Kingdom of Hungary.

- Norwegianization: Former policy carried out by the Norwegian government directed at the Sami and later the Kven people of the Sapmi region in Northern Norway.

- Germanisation: Prussian discrimination of Western Slavs in the 19th century, such as the removal of Polish from secondary (1874) and primary (1886) schools, the use of corporal punishment leading to such events as the Września school strike.

- Russification: 19th century policies on the territories seized due to partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, such as banning Polish, Lithuanian and Belarusian in public places (1864), later (1880s), Polish was banned in schools and offices of Congress Poland. Ukrainian and Romanian were also discriminated against. Under the Russian Empire there were some attempts in 1899–1917 to make Russian the only official language of Finland. In the Soviet Union, following the phase of Korenizatsiya ("indigenization") and before Perestroika (late 1930s to late 1980s), Russian was called "the language of friendship of nations" to the disadvantage of other languages of the Soviet Union.

- Anti-Hungarian Slovak language law

- Dutch in Belgium after its independence in 1830. French was for a long time the only official language and the only language of education, administration, law and justice despite Dutch being the most common language. This has led to widespread language shift in Brussels. Discrimination slowly faded over the decades and formally ended in the 1960s, when the Dutch version of the constitution became equal to the French version.

- The russification and restraining of the linguistic rights of federal subjects in the Russian Federation, most notably in Tatarstan.

- Serb organisations in Montenegro have reported discrimination of Serbian.[34]

In the United States

Perpetuation of discriminatory practices through terminology

Here and elsewhere the terms 'standard' and 'non-standard' make analysis of linguicism difficult. These terms are used widely by linguists and non-linguists when discussing varieties of American English that engender strong opinions, a false dichotomy which is rarely challenged or questioned. This has been interpreted by linguists Nicolas Coupland, Rosina Lippi-Green, and Robin Queen (among others) as a discipline-internal lack of consistency which undermines progress; if linguists themselves cannot move beyond the ideological underpinnings of 'right' and 'wrong' in language, there is little hope of advancing a more nuanced understanding in the general population.[35][36]

African-Americans

Because some African-Americans speak a particular non-standard variety of English which is often seen as substandard, they are often targets of linguicism. AAVE is often perceived by members of mainstream American society as indicative of low intelligence or limited education, and as with many other non-standard dialects and especially creoles, it has sometimes been called "lazy" or "bad" English.

The linguist John McWhorter has described this particular form of linguicism as particularly problematic in the United States, where non-standard linguistic structures are often deemed "incorrect" by teachers and potential employers in contrast to other countries such as Morocco, Finland and Italy where diglossia (the ability to switch between two or more dialects or languages) is an accepted norm, and non-standard usage in conversation is seen as a mark of regional origin, not of intellectual capacity or achievement.

For example, an African-American who uses a typical AAVE sentence such as "He be comin' in every day and sayin' he ain't done nothing" may be judged as having a deficient command of grammar, whereas, in fact, such a sentence is constructed based on a complex grammar which is different from that of standard English, not a degenerate form of it.[37] A listener may misjudge the user of such a sentence to be unintellectual or uneducated. The speaker may be intellectually capable, educated, and proficient in standard English, but chose to say the sentence in AAVE for social and sociolinguistic reasons such as the intended audience of the sentence, a phenomenon known as code switching.

Hispanic Americans and linguicism

Another form of linguicism is evidenced by the following: in some parts of the United States, a person who has a strong Mexican accent and uses only simple English words may be thought of as poor, poorly educated, and possibly an illegal immigrant. However, if the same person has a diluted accent or no noticeable accent at all and can use a myriad of words in complex sentences, they are likely to be perceived as more successful, better educated, and a legitimate citizen.

American Sign Language users

For centuries, users of American Sign Language (ASL) have faced linguistic discrimination based on the perception of the legitimacy of signed languages compared to spoken languages. This attitude was explicitly expressed in the Milan Conference of 1880 which set precedence for public opinion of manual forms of communication, including ASL, creating lasting consequences for members of the Deaf community.[38] The conference almost unanimously (save a handful of allies such as Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet), reaffirmed the use of oralism, instruction conducted exclusively in spoken language, as the preferred education method for Deaf individuals.[39] These ideas were outlined in eight resolutions which ultimately resulted in the removal of Deaf individuals from their own educational institutions, leaving generations of Deaf persons to be educated single-handedly by hearing individuals.[40]

Due to misconceptions about ASL, it was not recognized as its own, fully functioning language until recently. In the 1960s, linguist William Stokoe proved ASL to be its own language based on its unique structure and grammar, separate from that of English. Before this, ASL was thought to be merely a collection of gestures used to represent English. Because of its use of visual space, it was mistakenly believed that its users are of a lesser mental capacity. The misconception that ASL users are incapable of complex thought was prevalent, although this has decreased as further studies about its recognition of a language have taken place. For example, ASL users faced overwhelming discrimination for the supposedly "lesser" language that they use and were met with condescension especially when using their language in public.[41] Another way discrimination against ASL is evident is how, despite research conducted by linguists like Stokoe or Clayton Valli and Cecil Lucas of Gallaudet University, ASL is not always recognized as a language.[42] Its recognition is crucial both for those learning ASL as an additional language, and for prelingually-deaf children who learn ASL as their first language. Linguist Sherman Wilcox concludes that given that it has a body of literature and international scope, to single ASL out as unsuitable for a foreign language curriculum is inaccurate. Russel S. Rosen also writes about government and academic resistance to acknowledging ASL as a foreign language at the high school or college level, which Rosen believes often resulted from a lack of understanding about the language. Rosen and Wilcox's conclusions both point to discrimination ASL users face regarding its status as a language, that although decreasing over time is still present.[43]

In the medical community, there is immense bias against deafness and ASL. This stems from the belief that spoken languages are superior to sign languages.[44] Because 90% of deaf babies are born to hearing parents, who are usually unaware of the existence of the Deaf Community, they often turn to the medical community for guidance.[45] Medical and audiological professionals, who are typically biased against sign languages, encourage parents to get a cochlear implant for their deaf child in order for the child to use spoken language.[44] Research shows, however, that deaf kids without cochlear implants acquire ASL with much greater ease than deaf kids with cochlear implants acquire spoken English. In addition, medical professionals discourage parents from teaching ASL to their deaf kid to avoid compromising their English[46] although research shows that learning ASL does not interfere with a child's ability to learn English. In fact, the early acquisition of ASL proves to be useful to the child in learning English later on. When making a decision about cochlear implantation, parents are not properly educated about the benefits of ASL or the Deaf Community.[45] This is seen by many members of the Deaf Community as cultural and linguistic genocide.[46]

In Africa

- Anglophone Cameroonians: the central Cameroonian government has pushed francophonization in the English-speaking regions of the country despite constitutional stipulations on bilingualism.[47] Measures include appointing French-speaking teachers and judges (in regions with Common Law) despite local desires.

- South Africa: Carolyn McKinley[48] is highly critical of the language policy in the South African educational system, which she describes as 'anglonormatif', because the increasing anglicisation becomes 'normative' in the education system. The universities of Pretoria, Free State and Unisa want to anglicise completely.

In the Middle East

- The Coptic language: At the turn of the 8th century, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan decreed that Arabic would replace Koine Greek and Coptic as the administrative language. Literary Coptic gradually declined within a few hundred years and suffered violent persecutions, especially under the Mamluks, leading to its virtual extinction by the 17th century.

- Kurdish: Kurdish remains banned in Syria as of 2005.[49] Until August 2002, the Turkish government placed severe restrictions on the use of Kurdish, including a ban on its use in education and broadcast media.[50][51]

In Asia

- Suppression of Korean during Japanese rule in Korea, 1910 to 1945.

- Anti-Chinese legislation in Indonesia

- The brutality and linguicism against Tamils in Sri Lanka which took thousands of Tamil lives because of their language. This was rooted from "The Sinhala Only Act", formerly the Official Language Act No. 33 of 1956, that was passed in the Parliament of Ceylon in 1956. Black July was the peak of the violence against Tamils in 1983.[52]

- China: In the 2000s the Chinese government began promoting the use of Mandarin Chinese in areas where Cantonese is spoken. In 2010 this gave rise to the Guangzhou Television Cantonese controversy. This has also been a point of contention with Hong Kong, which is located in the general area where Cantonese is spoken. Cantonese has become a means of asserting Hong Kong's political identity as separate from mainland China.

Texts

Linguicism applies to written, spoken, or signed languages. The quality of a book or article may be judged by the language in which it is written. In the scientific community, for example, those who evaluated a text in two language versions, English and the national Scandinavian language, rated the English-language version as being of higher scientific content.[53]

The Internet operates a great deal using written language. Readers of a web page, Usenet group, forum post, or chat session may be more inclined to take the author seriously if the language is written in accordance with the standard language.

Music

A catalog of contemporary episodes of linguistic bigotry reported in the media has been assembled by critical applied linguist, Steven Talmy, which can be found here

Prejudice

In contrast to the previous examples of linguistic prejudice, linguistic discrimination involves the actual treatment of individuals based on use of language. Examples may be clearly seen in the workplace, in marketing, and in education systems. For example, some workplaces enforce an English-only policy, which is part of an American political movement that pushes for English to be accepted as the official language. In the United States, the federal law, Titles VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects non-native speakers from discrimination in the workplace based on their national origin or use of dialect. There are state laws which also address the protection of non-native speakers, such as the California Fair Employment and Housing Act. However, industries often argue in retrospect that clear, understandable English is often needed in specific work settings in the U.S.[1]

See also

- Linguistic insecurity

- Schizoglossia

- Standard language ideology

- Cultural assimilation

- Cultural genocide

- Indigenous language

- Language death

- Language ideology

- Language policy

- Linguistic imperialism

- Linguistic profiling

- Minoritized language

- Nonstandard dialect

- Official language

- Linguistic prescriptivism

- Prestige (sociolinguistics)

- Economics of language

- Raciolinguistics

References

- Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove (1988), Multilingualism and the education of minority children.

- The Legal Aid Society-Employment Law Center, & the ACLU Foundation of North California (2002). Language Discrimination: Your Legal Rights. http://www.aclunc.org/library/publications/asset_upload_file489_3538.pdf Archived 4 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Quoted in Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove, and Phillipson, Robert, "'Mother Tongue': The Theoretical and Sociopolitical Construction of a Concept." In Ammon, Ulrich (ed.) (1989). Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties, p. 455. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 3-11-011299-X.

- Anna Wierzbicka, Professor of Linguistics, Australian National University and author of 'Imprisoned by English, The Hazards of English as a Default Language, written in Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM), the universally convertible currency of communication, which can serve as a common auxiliary inter-language for speakers of different languages and a global means for clarifying, elucidating, storing, and comparing ideas" (194) (book review)

- Ebbe Dommisse, Single dominant tongue keeps inequality in place, 16 November 2016. The Business Day

- Bresnahan, M. J., Ohashi, R., Nebashi, R., Liu, W. Y., & Shearman, S. M. (2002). Attitudinal and affective response toward accented English. Language and Communication, 22, 171–185.

- "HLW: Word Forms: Processes: English Accents".

- Bradac, J. J. (1990). Language attitudes and impression formation. In H. Giles & W. P. Robinson (Eds.), Handbook of language and social psychology (pp. 387–412). London: John Wiley.

- Lippi-Green, Rosina (2012). English with an Accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States (Second ed.). 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-415-55911-9.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Jaspal, R. (2009). Language and social identity: a psychosocial approach. Psych-Talk, 64, 17-20.

- Mufwene, Salikoko (2002). "Colonisation, globalisation, and the future of languages in the twenty-first century". International Journal on Multicultural Societies. 4 (2): 162–193. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.109.2253.

- Mufwene, Salikoko; Vigouroux, Cécile B. (2008). Globalization and language vitality: Perspectives from Africa.

- Hamel, Rainer Enrique (1995), Linguistic Human Rights, DE GRUYTER MOUTON, doi:10.1515/9783110866391.271, ISBN 978-3-11-086639-1 Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help) - Szasz, Margaret Connell (April 2009). "Colin G. Calloway. White People, Indians, and Highlanders: Tribal People and Colonial Encounters in Scotland and America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. Pp. 368. $35.00 (cloth)". Journal of British Studies. 48 (2): 522–524. doi:10.1086/598899. ISSN 0021-9371.

- Parameswaran, Radhika E. (February 1997). "Colonial Interventions and the Postcolonial Situation in India". Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands). 59 (1): 21–41. doi:10.1177/0016549297059001003. ISSN 0016-5492.

- Kamoche, Jidlaph G.; Thiong'o, Ngũugĩ wa (1987). "Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature". World Literature Today. 61 (2): 339. doi:10.2307/40143257. ISSN 0196-3570. JSTOR 40143257.

- Chitpin, Stephanie; Portelli, John P., eds. (8 January 2019). Confronting Educational Policy in Neoliberal Times. doi:10.4324/9781315149875. ISBN 9781315149875.

- Hebblethwaite, Benjamin (2012). "French and underdevelopment, Haitian Creole and development: Educational language policy problems and solutions in Haiti". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 27 (2): 255–302. doi:10.1075/jpcl.27.2.03heb. ISSN 0920-9034.

- Bunyi, Grace (July 1999). "Rethinking the place of African indigenous languages in African education". International Journal of Educational Development. 19 (4–5): 337–350. doi:10.1016/s0738-0593(99)00034-6. ISSN 0738-0593.

- Conrad, Andrew W. Fishman, Joshua A. Rubal-Lopez, Alma. (13 October 2011). Post-Imperial English : Status Change in Former British and American Colonies, 1940-1990. ISBN 978-3-11-087218-7. OCLC 979587836.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lin, Angel; Martin, Peter, eds. (31 December 2005). Decolonisation, Globalisation. doi:10.21832/9781853598265. ISBN 9781853598265.

- Rannut, Mart (2010). Linguistic human rights: Overcoming linguistic discrimination (Vol. 67). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-086639-1.

- Tully, Stephen (2005). "UN: Convention on Rights of the Child, 1989". International Documents on Corporate Responsibility. doi:10.4337/9781845428297.00029. ISBN 9781845428297.

- Canagarajah, Suresh; Said, Selim Ben (2010), "Linguistic imperialism", The Routledge Handbook of Applied Linguistics, Routledge, doi:10.4324/9780203835654.ch27, ISBN 978-0-203-83565-4

- Evans, Julie; Grimshaw, Patricia; Phillips, David (21 August 2003). Equal Subjects, Unequal Rights. Manchester University Press. doi:10.7228/manchester/9780719060038.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-7190-6003-8.

- Brock-Utne, Birgit (2003). "The language question in Africa in the light of globalisation, social justice and democracy". International Journal of Peace Studies. 8 (2): 67–87. JSTOR 41852902.

- Cote, David (2014). "The right to language use in South African criminal courts" (PDF). Doctoral Dissertation, University of Cape Town.

- Schütz, H.; Six, B. (1996). "How strong is the relationship between prejudice and discrimination? A meta-analytic answer". International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 20 (3–4): 441–462. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(96)00028-4.

- Whitley, B.E., & Kite, M.E. (2010) The Psychology of Prejudice and Discrimination. Ed 2. pp.379-383. Cencage Learning: Belmont.

- Richard Y. Bourhis & Pierre Foucher, "Bill 103: Collective Rights and the declining vitality of the English-speaking communities of Quebec " Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Canadian Institute for Research on Linguistic Minorities, Version 3, November 25, 2010

- Louis N. Christofides & Robert Swidinsky, "The Economic Returns to the Knowledge and Use of a Second Official Language: English in Quebec and French in the Rest-of-Canada", Canadian Public Policy – Analyse de Politiques Vol. XXXVI, No. 2 2010

- Michele Gazzola, Multilingual communication for whom? Language policy and fairness in the European Union, European Union Politics, 2016, Vol. 17(4) 546–569

- Arnove, R. F.; Graff, H. J. (11 November 2013). National Literacy Campaigns: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781489905055. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Primary education: a report of the Advisory Council on Education in Scotland, Scottish Education Department 1946, p. 75

- "Montenegrin Serbs Allege Language Discrimination". Balkan Insight. 20 October 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Coupland, N. (1999). "Sociolinguistic Prevarication About 'Standard English'" Review article appearing in Tony Bex and Richard J. Watts (eds) Standard English: the Widening Debate London:Routledge

- Lippi-Green, R. (2012) English with an Accent: Language, Ideology and Discrimination in the U.S.. Second revised, expanded edition. New York: Routledge.

- Dicker, Susan J. (2nd ed., 2003). Languages in America: A Pluralist View, pp. 7-8. Multilingual Matters Ltd. ISBN 1-85359-651-5.

- Berke, Jame (30 January 2017). "Deaf History - Milan 1880". Very Well. Archived from the original on 1 January 1970. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- Traynor, Bob (1 June 2016). "The International Deafness Controversy of 1880". Hearing Health and Technology Matters.

- "Milan Conference of 1880". Weebly.

- Stewart, David A.; Akamatsu, C. Tane (1 January 1988). "The Coming of Age of American Sign Language". Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 19 (3): 235–252. doi:10.1525/aeq.1988.19.3.05x1559y. JSTOR 3195832.

- "ASL as a Foreign Language Fact Sheet". www.unm.edu. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Rosen, Russell S. (1 January 2008). "American Sign Language as a Foreign Language in U.S. High Schools: State of the Art". The Modern Language Journal. 92 (1): 10–38. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00684.x. JSTOR 25172990.

- Hyde, Merv; Punch, Renée; Komesaroff, Linda (1 January 2010). "Coming to a Decision About Cochlear Implantation: Parents Making Choices for their Deaf Children". Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 15 (2): 162–178. doi:10.1093/deafed/enq004. JSTOR 42659026. PMID 20139157.

- Crouch, Robert A. (1 January 1997). "Letting the Deaf Be Deaf Reconsidering the Use of Cochlear Implants in Prelingually Deaf Children". The Hastings Center Report. 27 (4): 14–21. doi:10.2307/3528774. JSTOR 3528774. PMID 9271717.

- SKUTNABB-KANGAS, TOVE; Solomon, Andrew; Skuttnab-Kangas, Tove (1 January 2014). Deaf Gain. Raising the Stakes for Human Diversity. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 492–502. ISBN 9780816691227. JSTOR 10.5749/j.ctt9qh3m7.33.

- Foretia, Denis (21 March 2017). "Cameroon continues its oppression of English speakers". The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Associate professor in the education department of the University of Cape Town and author of 'Language and Power in Post-Colonial Schooling: Ideologies in Practice'

- Repression of Kurds in Syria is widespread (pdf), Amnesty International Report, March 2005.

- Special Focus Cases: Leyla Zana, Prisoner of Conscience Archived 2005-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Kurdish performers banned, Appeal from International PEN Archived 2012-01-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Haviland, Charles (23 July 2013). "Remembering Sri Lanka's Black July". BBC. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- Jenkins, Jennifer (2003). World Englishes: A Resource Book for Students, p. 200. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25805-7.

Literature

- Skutnabb-Kangas et al. (eds.), Linguistic human rights: overcoming linguistic discrimination, Walter de Gruyter (1995), ISBN 3-11-014878-1.

- R. Wodak and D. Corson (eds.), Language policy and political issues in education, Springer, ISBN 0-7923-4713-7.