Inquisition

The Inquisition, in historical ecclesiastical parlance also referred to as the "Holy Inquisition", was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy. The Inquisition started in 12th-century France to combat religious dissent, in particular the Cathars and the Waldensians. Other groups investigated later included the Spiritual Franciscans, the Hussites (followers of Jan Hus) and the Beguines. Beginning in the 1250s, inquisitors were generally chosen from members of the Dominican Order, replacing the earlier practice of using local clergy as judges.[1] The term Medieval Inquisition covers these courts up to the mid-15th century.

During the Late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, the concept and scope of the Inquisition significantly expanded in response to the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. It expanded to other European countries,[2] resulting in the Spanish Inquisition and Portuguese Inquisition. The Spanish and Portuguese operated inquisitorial courts throughout their empires in Africa, Asia, and the Americas (resulting in the Goa Inquisition, Peruvian Inquisition and Mexican Inquisition).[3] The Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions focused particularly on the issue of Jewish anusim and Muslim converts to Catholicism, partly because these minority groups were more numerous in Spain and Portugal than in many other parts of Europe, and partly because they were often considered suspect due to the assumption that they had secretly reverted to their previous religions.

With the exception of the Papal States, the institution of the Inquisition was abolished in the early 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and the Spanish American wars of independence in the Americas. The institution survived as part of the Roman Curia, but in 1908 it was renamed the "Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office". In 1965 it became the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.[4]

Definition and purpose

The term Inquisition comes from the Medieval Latin word "inquisitio", which referred to any court process that was based on Roman law, which had gradually come back into use during the late medieval period.[5] Today, the English term "Inquisition" can apply to any one of several institutions that worked against heretics (or other offenders against canon law) within the judicial system of the Roman Catholic Church. Although the term Inquisition is usually applied to ecclesiastical courts of the Catholic Church, it refers to a judicial process, not an organization. "Inquisitors" "...were called such because they applied a judicial technique known as inquisitio, which could be translated as "inquiry" or "inquest." In this process, which was already widely used by secular rulers (Henry II used it extensively in England in the twelfth century), an official inquirer called for information on a specific subject from anyone who felt he or she had something to offer."[6]

The Inquisition, as a church-court, had no jurisdiction over Moors and Jews as such.[7] Generally, the Inquisition was concerned only with the heretical behaviour of Catholic adherents or converts.[8]

The overwhelming majority of sentences seem to have consisted of penances like wearing a cross sewn on one's clothes, going on pilgrimage, etc.[9] When a suspect was convicted of unrepentant heresy, the inquisitorial tribunal was required by law to hand the person over to secular authorities for final sentencing, at which point a magistrate would determine the penalty, which was usually burning at the stake although the penalty varied based on local law.[10][11] The laws were inclusive of proscriptions against certain religious crimes (heresy, etc.), and the punishments included death by burning, although usually the penalty was banishment or imprisonment for life, which was generally commuted after a few years. Thus the inquisitors generally knew what would be the fate of anyone so remanded.[12]

The 1578 edition of the Directorium Inquisitorum (a standard Inquisitorial manual) spelled out the purpose of inquisitorial penalties: ... quoniam punitio non refertur primo & per se in correctionem & bonum eius qui punitur, sed in bonum publicum ut alij terreantur, & a malis committendis avocentur (translation: "... for punishment does not take place primarily and per se for the correction and good of the person punished, but for the public good in order that others may become terrified and weaned away from the evils they would commit").[13]

Origin

Before 1100, the Catholic Church suppressed what they believed to be heresy, usually through a system of ecclesiastical proscription or imprisonment, but without using torture,[2] and seldom resorting to executions.[14][15] Such punishments were opposed by a number of clergymen and theologians, although some countries punished heresy with the death penalty.[16] [17]

In the 12th century, to counter the spread of Catharism, prosecution of heretics became more frequent. The Church charged councils composed of bishops and archbishops with establishing inquisitions (the Episcopal Inquisition). The first Inquisition was temporarily established in Languedoc (south of France) in 1184. The murder of Pope Innocent's papal legate Pierre de Castelnau in 1208 sparked the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229). The Inquisition was permanently established in 1229 (Council of Toulouse), run largely by the Dominicans[18] in Rome and later at Carcassonne in Languedoc.

Medieval Inquisition

Historians use the term "Medieval Inquisition" to describe the various inquisitions that started around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition (1230s). These inquisitions responded to large popular movements throughout Europe considered apostate or heretical to Christianity, in particular the Cathars in southern France and the Waldensians in both southern France and northern Italy. Other Inquisitions followed after these first inquisition movements. The legal basis for some inquisitorial activity came from Pope Innocent IV's papal bull Ad extirpanda of 1252, which explicitly authorized (and defined the appropriate circumstances for) the use of torture by the Inquisition for eliciting confessions from heretics.[19] However, Nicholas Eymerich, the inquisitor who wrote the "Directorium Inquisitorum", stated: 'Quaestiones sunt fallaces et ineficaces' ("interrogations via torture are misleading and futile"). By 1256 inquisitors were given absolution if they used instruments of torture.[20]

In the 13th century, Pope Gregory IX (reigned 1227–1241) assigned the duty of carrying out inquisitions to the Dominican Order and Franciscan Order. By the end of the Middle Ages, England and Castile were the only large western nations without a papal inquisition. Most inquisitors were friars who taught theology and/or law in the universities. They used inquisitorial procedures, a common legal practice adapted from the earlier Ancient Roman court procedures.[21] They judged heresy along with bishops and groups of "assessors" (clergy serving in a role that was roughly analogous to a jury or legal advisers), using the local authorities to establish a tribunal and to prosecute heretics. After 1200, a Grand Inquisitor headed each Inquisition. Grand Inquisitions persisted until the mid 19th century.[22]

Early Modern European history

With the sharpening of debate and of conflict between the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Protestant societies came to see/use the Inquisition as a terrifying "Other",[23] while staunch Catholics regarded the Holy Office as a necessary bulwark against the spread of reprehensible heresies.

Witch-trials

While belief in witchcraft, and persecutions directed at or excused by it, were widespread in pre-Christian Europe, and reflected in Germanic law, the influence of the Church in the early medieval era resulted in the revocation of these laws in many places, bringing an end to traditional pagan witch hunts.[24] Throughout the medieval era mainstream Christian teaching had denied the existence of witches and witchcraft, condemning it as pagan superstition.[25] However, Christian influence on popular beliefs in witches and maleficium (harm committed by magic) failed to entirely eradicate folk belief in witches.

The fierce denunciation and persecution of supposed sorceresses that characterized the cruel witchhunts of a later age were not generally found in the first thirteen hundred years of the Christian era.[26] The medieval Church distinguished between "white" and "black" magic. Local folk practice often mixed chants, incantations, and prayers to the appropriate patron saint to ward off storms, to protect cattle, or ensure a good harvest. Bonfires on Midsummer's Eve were intended to deflect natural catastrophes or the influence of fairies, ghosts, and witches. Plants, often harvested under particular conditions, were deemed effective in healing.[27]

Black magic was that which was used for a malevolent purpose. This was generally dealt with through confession, repentance, and charitable work assigned as penance.[28] Early Irish canons treated sorcery as a crime to be visited with excommunication until adequate penance had been performed. In 1258 Pope Alexander IV ruled that inquisitors should limit their involvement to those cases in which there was some clear presumption of heretical belief.

The prosecution of witchcraft generally became more prominent throughout the late medieval and Renaissance era, perhaps driven partly by the upheavals of the era – the Black Death, Hundred Years' War, and a gradual cooling of the climate that modern scientists call the Little Ice Age (between about the 15th and 19th centuries). Witches were sometimes blamed.[29][30] Since the years of most intense witch-hunting largely coincide with the age of the Reformation, some historians point to the influence of the Reformation on the European witch-hunt.[31]

Dominican priest Heinrich Kramer was assistant to the Archbishop of Salzburg. In 1484 Kramer requested that Pope Innocent VIII clarify his authority to prosecute witchcraft in Germany, where he had been refused assistance by the local ecclesiastical authorities. They maintained that Kramer could not legally function in their areas.[32]

The papal bull Summis desiderantes affectibus sought to remedy this jurisdictional dispute by specifically identifying the dioceses of Mainz, Köln, Trier, Salzburg, and Bremen.[33] Some scholars view the bull as "clearly political".[34] The bull failed to ensure that Kramer obtained the support he had hoped for, in fact he was subsequently expelled from the city of Innsbruck by the local bishop, George Golzer, who ordered Kramer to stop making false accusations. Golzer described Kramer as senile in letters written shortly after the incident. This rebuke led Kramer to write a justification of his views on witchcraft in his book Malleus Maleficarum, written in 1486. In the book, Kramer stated his view that witchcraft was to blame for bad weather. The book is also noted for its animus against women.[26] Despite Kramer's claim that the book gained acceptance from the clergy at the university of Cologne, it was in fact condemned by the clergy at Cologne for advocating views that violated Catholic doctrine and standard inquisitorial procedure. In 1538 the Spanish Inquisition cautioned its members not to believe everything the Malleus said.[35]

Spanish Inquisition

Portugal and Spain in the late Middle Ages consisted largely of multicultural territories of Muslim and Jewish influence, reconquered from Islamic control, and the new Christian authorities could not assume that all their subjects would suddenly become and remain orthodox Roman Catholics. So the Inquisition in Iberia, in the lands of the Reconquista counties and kingdoms like León, Castile, and Aragon, had a special socio-political basis as well as more fundamental religious motives.

In some parts of Spain towards the end of the 14th century, there was a wave of violent anti-Judaism, encouraged by the preaching of Ferrand Martinez, Archdeacon of Écija. In the pogroms of June 1391 in Seville, hundreds of Jews were killed, and the synagogue was completely destroyed. The number of people killed was also high in other cities, such as Córdoba, Valencia, and Barcelona.[37]

One of the consequences of these pogroms was the mass conversion of thousands of surviving Jews. Forced baptism was contrary to the law of the Catholic Church, and theoretically anybody who had been forcibly baptized could legally return to Judaism. However, this was very narrowly interpreted. Legal definitions of the time theoretically acknowledged that a forced baptism was not a valid sacrament, but confined this to cases where it was literally administered by physical force. A person who had consented to baptism under threat of death or serious injury was still regarded as a voluntary convert, and accordingly forbidden to revert to Judaism.[38] After the public violence, many of the converted "felt it safer to remain in their new religion".[39] Thus, after 1391, a new social group appeared and were referred to as conversos or New Christians.

King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile established the Spanish Inquisition in 1478. In contrast to the previous inquisitions, it operated completely under royal Christian authority, though staffed by clergy and orders, and independently of the Holy See. It operated in Spain and in all Spanish colonies and territories, which included the Canary Islands, the Kingdom of Naples, and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America. It primarily focused upon forced converts from Islam (Moriscos, Conversos and secret Moors) and from Judaism (Conversos, Crypto-Jews and Marranos)—both groups still resided in Spain after the end of the Islamic control of Spain—who came under suspicion of either continuing to adhere to their old religion or of having fallen back into it.

In 1492 all Jews who had not converted were expelled from Spain; those who converted became nominal Catholics and thus subject to the Inquisition.

Inquisition in the Spanish overseas empire

In the Americas, King Philip II set up three tribunals (each formally titled Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición) in 1569, one in Mexico, Cartagena de Indias (in modern-day Colombia) and Peru. The Mexican office administered Mexico (central and southeastern Mexico), Nueva Galicia (northern and western Mexico), the Audiencias of Guatemala (Guatemala, Chiapas, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica), and the Spanish East Indies. The Peruvian Inquisition, based in Lima, administered all the Spanish territories in South America and Panama.

Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition formally started in Portugal in 1536 at the request of King João III. Manuel I had asked Pope Leo X for the installation of the Inquisition in 1515, but only after his death in 1521 did Pope Paul III acquiesce. At its head stood a Grande Inquisidor, or General Inquisitor, named by the Pope but selected by the Crown, and always from within the royal family. The Portuguese Inquisition principally focused upon the Sephardi Jews, whom the state forced to convert to Christianity. Spain had expelled its Sephardi population in 1492; many of these Spanish Jews left Spain for Portugal but eventually were subject to inquisition there as well.

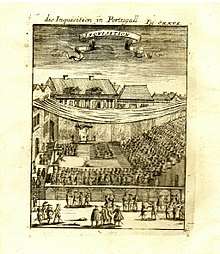

The Portuguese Inquisition held its first auto-da-fé in 1540. The Portuguese inquisitors mostly focused upon the Jewish New Christians (i.e. conversos or marranos). The Portuguese Inquisition expanded its scope of operations from Portugal to its colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa. In the colonies, it continued as a religious court, investigating and trying cases of breaches of the tenets of orthodox Roman Catholicism until 1821. King João III (reigned 1521–57) extended the activity of the courts to cover censorship, divination, witchcraft, and bigamy. Originally oriented for a religious action, the Inquisition exerted an influence over almost every aspect of Portuguese society: political, cultural, and social.

The Goa Inquisition, which began in 1560, was initiated by Jesuit priest Francis Xavier from his headquarters in Malacca, originally because of the New Christians who were living there and also in Goa and the region whose population had reverted to Judaism. The Goa inquisition also focused upon Catholic converts from Hinduism or Islam who were thought to have returned to their original ways. In addition, this inquisition prosecuted non-converts who broke prohibitions against the observance of Hindu or Muslim rites or interfered with Portuguese attempts to convert non-Christians to Catholicism.[40] Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques set it up in the palace of the Sabaio Adil Khan.

According to Henry Charles Lea, between 1540 and 1794, tribunals in Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra, and Évora resulted in the burning of 1,175 persons, the burning of another 633 in effigy, and the penancing of 29,590.[41] But documentation of 15 out of 689 autos-da-fé has disappeared, so these numbers may slightly understate the activity.[42]

Roman Inquisition

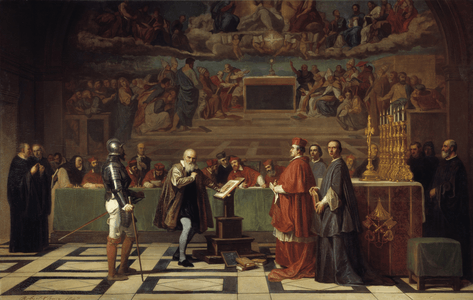

With the Protestant Reformation, Catholic authorities became much more ready to suspect heresy in any new ideas,[43] including those of Renaissance humanism,[44] previously strongly supported by many at the top of the Church hierarchy. The extirpation of heretics became a much broader and more complex enterprise, complicated by the politics of territorial Protestant powers, especially in northern Europe. The Catholic Church could no longer exercise direct influence in the politics and justice-systems of lands that officially adopted Protestantism. Thus war (the French Wars of Religion, the Thirty Years' War), massacre (the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre) and the missional[45] and propaganda work (by the Sacra congregatio de propaganda fide)[46] of the Counter-Reformation came to play larger roles in these circumstances, and the Roman law type of a "judicial" approach to heresy represented by the Inquisition became less important overall. In 1542 Pope Paul III established the Congregation of the Holy Office of the Inquisition as a permanent congregation staffed with cardinals and other officials. It had the tasks of maintaining and defending the integrity of the faith and of examining and proscribing errors and false doctrines; it thus became the supervisory body of local Inquisitions.[47] Arguably the most famous case tried by the Roman Inquisition was that of Galileo Galilei in 1633.

The penances and sentences for those who confessed or were found guilty were pronounced together in a public ceremony at the end of all the processes. This was the sermo generalis or auto-da-fé.[48] Penances (not matters for the civil authorities) might consist of a pilgrimage, a public scourging, a fine, or the wearing of a cross. The wearing of two tongues of red or other brightly colored cloth, sewn onto an outer garment in an "X" pattern, marked those who were under investigation. The penalties in serious cases were confiscation of property by the Inquisition or imprisonment. This led to the possibility of false charges to enable confiscation being made against those over a certain income, particularly rich marranos. Following the French invasion of 1798, the new authorities sent 3,000 chests containing over 100,000 Inquisition documents to France from Rome.

Ending of the Inquisition in the 19th and 20th centuries

The wars of independence of the former Spanish colonies in the Americas concluded with the abolition of the Inquisition in every quarter of Hispanic America between 1813 and 1825.

By decree of Napoleon's government in 1797, the Inquisition in Venice was abolished in 1806.[49]

In Portugal, in the wake of the Liberal Revolution of 1820, the "General Extraordinary and Constituent Courts of the Portuguese Nation" abolished the Portuguese inquisition in 1821.

The last execution of the Inquisition was in Spain in 1826.[50] This was the execution by garroting of the school teacher Cayetano Ripoll for purportedly teaching Deism in his school.[50] In Spain the practices of the Inquisition were finally outlawed in 1834.[51]

In Italy, after the restoration of the Pope as the ruler of the Papal States in 1814, the activity of the Papal States Inquisition continued on until the mid-19th century, notably in the well-publicised Mortara affair (1858–1870). In 1908 the name of the Congregation became "The Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office", which in 1965 further changed to "Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith", as retained to the present day.

Statistics

Beginning in the 19th century, historians have gradually compiled statistics drawn from the surviving court records, from which estimates have been calculated by adjusting the recorded number of convictions by the average rate of document loss for each time period. Gustav Henningsen and Jaime Contreras studied the records of the Spanish Inquisition, which list 44,674 cases of which 826 resulted in executions in person and 778 in effigy (i.e. a straw dummy was burned in place of the person).[52] William Monter estimated there were 1000 executions between 1530–1630 and 250 between 1630–1730.[53] Jean-Pierre Dedieu studied the records of Toledo's tribunal, which put 12,000 people on trial.[54] For the period prior to 1530, Henry Kamen estimated there were about 2,000 executions in all of Spain's tribunals.[55] Italian Renaissance history professor and Inquisition expert Carlo Ginzburg had his doubts about using statistics to reach a judgment about the period. "In many cases, we don’t have the evidence, the evidence has been lost," said Ginzburg.[56]

Appearance in popular media

- In the Monty Python comedy team's Spanish Inquisition sketches, an inept Inquisitor group repeatedly bursts into scenes after someone utters the words "I didn't expect a kind of Spanish Inquisition", screaming "Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!" The Inquisition then uses ineffectual forms of torture, including a dish-drying rack, soft cushions and a comfy chair.

- The 1982 novel Baltasar and Blimunda by José Saramago, portrays how the Portuguese Inquisition impacts the fortunes of the title characters as well as several others from history, including the priest and aviation pioneer Bartolomeu de Gusmão.

- The 1981 comedy film History of the World, Part I, produced and directed by Mel Brooks, features a segment on the Spanish Inquisition.

- Inquisitio is a French television series set in the Middle Ages.

- In the novel Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco, there is some discussion about various sects of Christianity and inquisition, a small discussion about the ethics and purpose of inquisition, and a scene of Inquisition. In the movie by the same name, The Inquisition plays a prominent role including torture and a burning at the stake.

- In the novel La Catedral del Mar by Ildefonso Falcones, and Netflix series Cathedral of the Sea based on the novel, there are scenes of inquisition investigations in small towns and a great scene in Barcelona.

- Milos Foreman's "Goya's Ghosts", released June 9, 2007 in the US, brings to light the stories behind some of Spanish painter Francisco Goya's paintings during the Spanish Inquisition, particularly one of a priest condemning and imprisoning a beautiful woman for his own profit. Her family retaliates, but cannot save her.

- A fictionalized version of the Inquisition serves as a basis for the action-adventure horror stealth game A Plague Tale: Innocence.

See also

- Black legend (Spain)

- Black Legend of the Spanish Inquisition

- Cathars

- List of people executed in the Papal States

- Witch-cult hypothesis

- Witch trials in the early modern period

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

- Historical revision of the Inquisition

- Marian Persecutions of Protestant heretics

- Vatican Secret Archives

Documents and works

Notable inquisitors

Notable cases

- Trial of Joan of Arc

- Trial of Galileo Galilei

- Edgardo Mortara's abduction

- Logroño witch trials

- Caterina Tarongí

- Execution of Giordano Bruno

Repentance

- Apologies by Pope John Paul II

References

- Peters, Edward. "Inquisition", p. 54.

-

Lea, Henry Charles (1888). "Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded". A History of the Inquisition In The Middle Ages. 1. ISBN 1-152-29621-3.

The judicial use of torture was as yet happily unknown...

- Murphy, Cullen (2012). God's Jury. New York: Mariner Books – Houghton, Miflin, Harcourt. p. 150.

- "Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith - Profile". Vatican.va. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Peters, Edwards. "Inquisition", p. 12

- "Internet History Sourcebooks Project". Fordham.edu. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Marvin R. O'Connell. "The Spanish Inquisition: Fact Versus Fiction". Ignatiusinsight.com. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D., in Saraiva, Antonio Jose. The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765 (Brill, 2001), Introduction pp. XXX.

- "Internet History Sourcebooks Project". legacy.fordham.edu. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Peters writes: "When faced with a convicted heretic who refused to recant, or who relapsed into heresy, the inquisitors were to turn him over to the temporal authorities – the "secular arm" – for animadversio debita, the punishment decreed by local law, usually burning to death." (Peters, Edwards. "Inquisition", p. 67.)

- Lea, Henry Charles. "Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded". A History of the Inquisition In The Middle Ages. 1. ISBN 1-152-29621-3. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

Obstinate heretics, refusing to abjure and return to the Church with due penance, and those who after abjuration relapsed, were to be abandoned to the secular arm for fitting punishment.

- Kirsch, Jonathan. The Grand Inquisitors Manual: A History of Terror in the Name of God. HarperOne. ISBN 0-06-081699-6.

- Directorium Inquisitorum, edition of 1578, Book 3, pg. 137, column 1. Online in the Cornell University Collection; retrieved 2008-05-16.

- Foxe, John. "Chapter V" (PDF). Foxe's Book of Martyrs.

-

Blötzer, J. (1910). "Inquisition". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

... in this period the more influential ecclesiastical authorities declared that the death penalty was contrary to the spirit of the Gospel, and they themselves opposed its execution. For centuries this was the ecclesiastical attitude both in theory and in practice. Thus, in keeping with the civil law, some Manichæans were executed at Ravenna in 556. On the other hand, Elipandus of Toledo and Felix of Urgel, the chiefs of Adoptionism and Predestinationism, were condemned by councils, but were otherwise left unmolested. We may note, however, that the monk Gothescalch, after the condemnation of his false doctrine that Christ had not died for all mankind, was by the Synods of Mainz in 848 and Quiercy in 849 sentenced to flogging and imprisonment, punishments then common in monasteries for various infractions of the rule.

-

Blötzer, J. (1910). "Inquisition". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

[...] the occasional executions of heretics during this period must be ascribed partly to the arbitrary action of individual rulers, partly to the fanatic outbreaks of the overzealous populace, and in no wise to ecclesiastical law or the ecclesiastical authorities.

- Lea, Henry Charles. "Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded". A History of the Inquisition In The Middle Ages. 1. ISBN 1-152-29621-3.

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Inquisition". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Bishop, Jordan (2006). "Aquinas on Torture". New Blackfriars. 87 (1009): 229–237. doi:10.1111/j.0028-4289.2006.00142.x.

- Larissa Tracy, Torture and Brutality in Medieval Literature: Negotiations of National Identity, (Boydell and Brewer Ltd, 2012), 22; "In 1252 Innocent IV licensed the use of torture to obtain evidence from suspects, and by 1256 inquisitors were allowed to absolve each other if they used instruments of torture themselves, rather than relying on lay agents for the purpose...".

- Peters, Edwards. "Inquisition", p. 12.

- Lea, Henry Charles. A History of the Inquisition of Spain, vol. 1, appendix 2

-

Compare Haydon, Colin (1993). Anti-Catholicism in eighteenth-century England, c. 1714-80: a political and social study. Studies in imperialism. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-7190-2859-0. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

The popular fear of Popery focused on the persecution of heretics by the Catholics. It was generally assumed that, whenever it was in their power, Papists would extirpate heresy by force, seeing it as a religious duty. History seemed to show this all too clearly. [...] The Inquisition had suppressed, and continued to check, religious dissent in Spain. Papists, and most of all, the Pope, delighted in the slaughter of heretics. 'I most firmly believed when I was as boy', William Cobbett [born 1763], coming originally from rural Surrey, recalled, 'that the Pope was a prodigious woman, dressed in a dreadful robe, which had been made red by being dipped in the blood of Protestants'.

- Hutton, Ronald (1991). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Oxford, UK and Cambridge, US: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-17288-8, p. 257

- Behringer, "Witches and Witch-hunts: a Global History", p. 31 (2004). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Thurston, Herbert. "Witchcraft." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 12 Jul. 2015

- "Plants in Medieval Magic – The Medieval Garden Enclosed – The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York". blog.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Del Rio, Martin Antoine and Maxwell-Stuart, P. G., Investigations Into Magic, Manchester University Press, 2000, ISBN 9780719049767

- Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe, (49)

- Heinrich Institoris, Heinrich, Sprenger, Jakob, Summers, Montague; The Malleus maleficarum of Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger; Dover Publications; New edition, 1 June 1971; ISBN 0-486-22802-9

- Brian P. Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe (in German) (London/New York 2013 ed.), p. 110,

„The period during which all of this reforming activity and conflict took place, the age of the Reformation, spanned the years 1520–1650. Since these years include the period when witch-hunting was most intense, some historians have claimed that the Reformation served as the mainspring of the entire European witch-hunt."

- Kors, Alan Charles; Peters, Edward (2000). Witchcraft in Europe, 400-1700: A Documentary History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1751-9. p. 177

- "Internet History Sourcebooks Project". sourcebooks.fordham.edu.

- Darst, David H., "Witchcraft in Spain: The Testimony of Martín de Castañega's Treatise on Superstition and Witchcraft (1529)", Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 1979, vol. 123, issue 5, p. 298

- Witchcraft and magic in Europe: the Middle Ages, p. 241 (Jolly, Raudvere, & Peters(eds.) 2002

- Saint Dominic Guzmán presiding over an Auto da fe, Prado Museum. Retrieved 2012-08-26

- Kamen, Spanish Inquisition, p. 17. Kamen cites approximate numbers for Valencia (250) and Barcelona (400), but no solid data about Córdoba.

- Raymond of Peñafort, Summa, lib. 1 p.33, citing D.45 c.5.

- Kamen, Spanish Inquisition, p. 10.

- Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D., in Saraiva, Antonio Jose. The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765 (Brill, 2001), pgs. 345-7

- H.C. Lea, A History of the Inquisition of Spain, vol. 3, Book 8

- Saraiva, António José; Salomon, Herman Prins; Sassoon, I. S. D. (2001) [First published in Portuguese in 1969]. The Marrano Factory: the Portuguese Inquisition and its New Christians 1536-1765. Brill. p. 102. ISBN 978-90-04-12080-8. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- Stokes, Adrian Durham (2002) [1955]. Michelangelo: a study in the nature of art. Routledge classics (2 ed.). Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-415-26765-6. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

Ludovico is so immediately settled in heaven by the poet that some commentators have divined that Michelangelo is voicing heresy, that is to say, the denial of purgatory.

- Erasmus, the arch-Humanist of the Renaissance, came under suspicion of heresy, see

Olney, Warren (2009). Desiderius Erasmus; Paper Read Before the Berkeley Club, March 18, 1920. BiblioBazaar. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-113-40503-6. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

Thomas More, in an elaborate defense of his friend, written to a cleric who accused Erasmus of heresy, seems to admit that Erasmus was probably the author of Julius.

- Vidmar, John C. (2005). The Catholic Church Through the Ages. New York: Paulist Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-8091-4234-7.

- Soergel, Philip M. (1993). Wondrous in His Saints: Counter Reformation Propaganda in Bavaria. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 239. ISBN 0-520-08047-5.

- "Christianity | The Inquisition". The Galileo Project. Retrieved 2012-08-26

- Blötzer, J. (1910). "Inquisition". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- "The Public Gardens of Venice and the Inquisition". www.venetoinside.com.

- Law, Stephen (2011). Humanism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-19-955364-8.

- "Spanish Inquisition - Spanish history [1478-1834]". Britannica.com. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Gustav Henningsen, The Database of the Spanish Inquisition. The relaciones de causas project revisited, in: Heinz Mohnhaupt, Dieter Simon, Vorträge zur Justizforschung, Vittorio Klostermann, 1992, pp. 43-85.

- W. Monter, Frontiers of Heresy: The Spanish Inquisition from the Basque Lands to Sicily, Cambridge 2003, p. 53.

- Jean-Pierre Dedieu, Los Cuatro Tiempos, in Bartolomé Benassar, Inquisición Española: poder político y control social, pp. 15-39.

- H. Kamen, Inkwizycja Hiszpańska, Warszawa 2005, p. 62; and H. Rawlings, The Spanish Inquisition, Blackwell Publishing 2004, p. 15.

- "Vatican downgrades Inquisition toll". Nbcnews.com. 15 June 2004. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

Bibliography

- Adler, E. N. (April 1901). "Auto de fe and Jew". The Jewish Quarterly Review. University of Pennsylvania Press. 13 (3): 392–437. doi:10.2307/1450541. JSTOR 1450541.

- Burman, Edward, The Inquisition: The Hammer of Heresy (Sutton Publishers, 2004) ISBN 0-7509-3722-X. A new edition of a book first published in 1984, a general history based on the main primary sources.

- Carroll, Warren H., Isabel: the Catholic Queen Front Royal, Virginia, 1991 (Christendom Press)

- Foxe, John (1997) [1563]. Chadwick, Harold J. (ed.). The new Foxe's book of martyrs/John Foxe; rewritten and updated by Harold J. Chadwick. Bridge-Logos. ISBN 0-88270-672-1.

- Given, James B, Inquisition and Medieval Society (Cornell University Press, 2001)

- Kamen, Henry, The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision. (Yale University Press, 1999); ISBN 0-300-07880-3. This revised edition of his 1965 original contributes to the understanding of the Spanish Inquisition in its local context.

- Lea, Henry Charles, A History of the Inquisition of Spain, 4 volumes (New York and London, 1906–7)

- Parker, Geoffrey (1982). "Some Recent Work on the Inquisition in Spain and Italy". Journal of Modern History. 54 (3).

- Peters, Edward (1989). Inquisition. U of California Press.

- Twiss, Miranda (2002). The Most Evil Men And Women In History. Michael O'Mara Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85479-488-8.

- Walsh, William Thomas, Characters of the Inquisition (TAN Books and Publishers, Inc, 1940/97); ISBN 0-89555-326-0

- Whitechapel, Simon, Flesh Inferno: Atrocities of Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition (Creation Books, 2003); ISBN 1-84068-105-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Inquisition. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Inquisition |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |