Francis of Assisi

Francis of Assisi (Italian: San Francesco d'Assisi; Latin: Sanctus Franciscus Assisiensis), born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, informally named as Francesco (1181/1182 – 3 October 1226),[2] was an Italian Catholic friar, deacon, philosopher, mystic and preacher. [8] He founded the men's Order of Friars Minor, the women's Order of Saint Clare, the Third Order of Saint Francis and the Custody of the Holy Land. Francis is one of the most venerated religious figures in Christianity.[3]

Francis of Assisi | |

|---|---|

The oldest surviving depiction of Saint Francis is a fresco near the entrance of the Benedictine abbey of Subiaco, painted between March 1228 and March 1229. He is depicted without the stigmata, but the image is a religious image and not a portrait.[1] | |

| Religious, Deacon, Confessor, Stigmatist and Founder of the Franciscan Order | |

| Born | Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone 1181 or 1182 Assisi, Duchy of Spoleto, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 3 October 1226 (aged 44 years)[2] Assisi, Umbria, Papal States[3] |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Anglican Communion[4] Lutheranism[5] Old Catholic Church |

| Canonized | 16 July 1228, Assisi, Papal States by Pope Gregory IX |

| Major shrine | Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi |

| Feast | 4 October |

| Patronage | Stowaways[6] Italy[7] Ecology[7] Animals[7] |

Pope Gregory IX canonized Francis on 16 July 1228. Along with Saint Catherine of Siena, he was designated Patron saint of Italy. He later became associated with patronage of animals and the natural environment, and it became customary for churches to hold ceremonies blessing animals on or near his feast day of 4 October. In 1219, he went to Egypt in an attempt to convert the Sultan to put an end to the conflict of the Crusades.[9] By this point, the Franciscan Order had grown to such an extent that its primitive organizational structure was no longer sufficient. He returned to Italy to organize the Order.

Once his community was authorized by the Pope, he withdrew increasingly from external affairs. Francis is also known for his love of the Eucharist.[10] In 1223, Francis arranged for the first Christmas live nativity scene.[11][12][2] According to Christian tradition, in 1224 he received the stigmata during the apparition of Seraphic angels in a religious ecstasy,[13] which would make him the second person in Christian tradition after St. Paul (Galatians 6:17) to bear the wounds of Christ's Passion.[14] He died during the evening hours of 3 October 1226, while listening to a reading he had requested of Psalm 142 (141).

Biography

Early life

Francis of Assisi was born in late 1181 or early 1182, one of several children of an Italian father, Pietro di Bernardone dei Moriconi, a prosperous silk merchant, and a French mother, Pica de Bourlemont, about whom little is known except that she was a noblewoman originally from Provence.[15] Pietro was in France on business when Francis was born in Assisi, and Pica had him baptized as Giovanni.[16] Upon his return to Assisi, Pietro took to calling his son Francesco ("the Frenchman"), possibly in honor of his commercial success and enthusiasm for all things French.[17] Since the child was renamed in infancy, the change can hardly have had anything to do with his aptitude for learning French, as some have thought.[2]

Indulged by his parents, Francis lived the high-spirited life typical of a wealthy young man.[13] As a youth, Francesco became a devotee of troubadours and was fascinated with all things Transalpine.[17] He was handsome, witty, gallant, and delighted in fine clothes. He spent money lavishly.[2] Although many hagiographers remark about his bright clothing, rich friends, and love of pleasures,[15] his displays of disillusionment toward the world that surrounded him came fairly early in his life, as is shown in the "story of the beggar". In this account, he was selling cloth and velvet in the marketplace on behalf of his father when a beggar came to him and asked for alms. At the conclusion of his business deal, Francis abandoned his wares and ran after the beggar. When he found him, Francis gave the man everything he had in his pockets. His friends quickly chided and mocked him for his act of charity. When he got home, his father scolded him in rage.[18]

Around 1202, he joined a military expedition against Perugia and was taken as a prisoner at Collestrada, spending a year as a captive. An illness caused him to re-evaluate his life. It is possible that his spiritual conversion was a gradual process rooted in this experience. Upon his return to Assisi in 1203, Francis returned to his carefree life. In 1205, Francis left for Apulia to enlist in the army of Walter III, Count of Brienne. A strange vision made him return to Assisi, having lost his taste for the worldly life.[13] According to hagiographic accounts, thereafter he began to avoid the sports and the feasts of his former companions. In response, they asked him laughingly whether he was thinking of marrying, to which he answered, "Yes, a fairer bride than any of you have ever seen", meaning his "Lady Poverty".[2]

On a pilgrimage to Rome, he joined the poor in begging at St. Peter's Basilica.[13] He spent some time in lonely places, asking God for spiritual enlightenment. He said he had a mystical vision of Jesus Christ in the forsaken country chapel of San Damiano, just outside Assisi, in which the Icon of Christ Crucified said to him, "Francis, Francis, go and repair My house which, as you can see, is falling into ruins." He took this to mean the ruined church in which he was presently praying, and so he sold some cloth from his father's store to assist the priest there for this purpose.[20] When the priest refused to accept the ill-gotten gains, an indignant Francis threw the coins on the floor.[2]

In order to avoid his father's wrath, Francis hid in a cave near San Damiano for about a month. When he returned to town, hungry and dirty, he was dragged home by his father, beaten, bound, and locked in a small storeroom. Freed by his mother during Bernardone's absence, Francis returned at once to San Damiano, where he found shelter with the officiating priest, but he was soon cited before the city consuls by his father. The latter, not content with having recovered the scattered gold from San Damiano, sought also to force his son to forego his inheritance by way of restitution. In the midst of legal proceedings before the Bishop of Assisi, Francis renounced his father and his patrimony.[2] Some accounts report that he stripped himself naked in token of this renunciation, and the Bishop covered him with his own cloak.[21][22]

For the next couple of months, Francis wandered as a beggar in the hills behind Assisi. He spent some time at a neighbouring monastery working as a scullion. He then went to Gubbio, where a friend gave him, as an alms, the cloak, girdle, and staff of a pilgrim. Returning to Assisi, he traversed the city begging stones for the restoration of St. Damiano's. These he carried to the old chapel, set in place himself, and so at length rebuilt it. Over the course of two years, he embraced the life of a penitent, during which he restored several ruined chapels in the countryside around Assisi, among them San Pietro in Spina (in the area of San Petrignano in the valley about a kilometer from Rivotorto, today on private property and once again in ruin); and the Porziuncola, the little chapel of St. Mary of the Angels in the plain just below the town.[2] This later became his favorite abode.[20] By degrees he took to nursing lepers, in the lazar houses near Assisi.

Founding of the Franciscan Orders

The Friars Minor

One morning in February 1208, Francis was hearing Mass in the chapel of St. Mary of the Angels, near which he had then built himself a hut. The Gospel of the day was the "Commissioning of the Twelve" from the Book of Matthew. The disciples are to go and proclaim that the Kingdom of God is at hand. Francis was inspired to devote himself to a life of poverty. Having obtained a coarse woolen tunic, the dress then worn by the poorest Umbrian peasants, he tied it around him with a knotted rope and went forth at once exhorting the people of the country-side to penance, brotherly love, and peace. Francis' preaching to ordinary people was unusual since he had no license to do so.[3]

His example drew others to him. Within a year Francis had eleven followers. The brothers lived a simple life in the deserted lazar house of Rivo Torto near Assisi; but they spent much of their time wandering through the mountainous districts of Umbria, making a deep impression upon their hearers by their earnest exhortations.[2]

In 1209 he composed a simple rule for his followers ("friars"), the Regula primitiva or "Primitive Rule", which came from verses in the Bible. The rule was "To follow the teachings of our Lord Jesus Christ and to walk in his footsteps". He then led his first eleven followers to Rome to seek permission from Pope Innocent III to found a new religious Order.[23] Upon entry to Rome, the brothers encountered Bishop Guido of Assisi, who had in his company Giovanni di San Paolo, the Cardinal Bishop of Sabina. The Cardinal, who was the confessor of Pope Innocent III, was immediately sympathetic to Francis and agreed to represent Francis to the pope. Reluctantly, Pope Innocent agreed to meet with Francis and the brothers the next day. After several days, the pope agreed to admit the group informally, adding that when God increased the group in grace and number, they could return for an official admittance. The group was tonsured.[24] This was important in part because it recognized Church authority and prevented his following from possible accusations of heresy, as had happened to the Waldensians decades earlier. Though a number of the Pope's counselors considered the mode of life proposed by Francis as unsafe and impractical, following a dream in which he saw Francis holding up the Basilica of St. John Lateran (the cathedral of Rome, thus the 'home church' of all Christendom), he decided to endorse Francis' Order. This occurred, according to tradition, on 16 April 1210, and constituted the official founding of the Franciscan Order.[3] The group, then the "Lesser Brothers" (Order of Friars Minor also known as the Franciscan Order or the Seraphic Order), were centered in the Porziuncola and preached first in Umbria, before expanding throughout Italy.[3] Francis chose never to be ordained a priest, although he was later ordained a deacon.[2]

The Poor Clares and the Third Order

From then on, the new Order grew quickly with new vocations. Hearing Francis preaching in the church of San Rufino in Assisi in 1211, the young noblewoman Clare of Assisi became deeply touched by his message and realized her calling. Her cousin Rufino, the only male member of the family in their generation, was also attracted to the new Order, which he joined. On the night of Palm Sunday, 28 March 1212, Clare clandestinely left her family's palace. Francis received her at the Porziuncola and thereby established the Order of Poor Ladies.[25] This was an Order for women, and he gave Clare a religious habit, or garment, similar to his own, before lodging her in a nearby monastery of Benedictine nuns until he could provide a suitable retreat for her, and for her younger sister, Caterina, and the other young women who had joined her. Later he transferred them to San Damiano,[3] to a few small huts or cells of wattle, straw, and mud, and enclosed by a hedge. This became the first monastery of the Second Franciscan Order, now known as Poor Clares.[2]

For those who could not leave their homes, he later formed the Third Order of Brothers and Sisters of Penance, a fraternity composed of either laity or clergy whose members neither withdrew from the world nor took religious vows. Instead, they observed the principles of Franciscan life in their daily lives.[3] Before long, this Third Order grew beyond Italy. The Third Order is now titled the Secular Franciscan Order.

Travels

Determined to bring the Gospel to all peoples of the World and convert them, after the example of the first disciples of Jesus, Francis sought on several occasions to take his message out of Italy. In the late spring of 1212, he set out for Jerusalem, but was shipwrecked by a storm on the Dalmatian coast, forcing him to return to Italy. On 8 May 1213, he was given the use of the mountain of La Verna (Alverna) as a gift from Count Orlando di Chiusi, who described it as “eminently suitable for whoever wishes to do penance in a place remote from mankind”.[26] The mountain would become one of his favourite retreats for prayer.[27]

In the same year, Francis sailed for Morocco, but this time an illness forced him to break off his journey in Spain. Back in Assisi, several noblemen (among them Tommaso da Celano, who would later write the biography of St. Francis), and some well-educated men joined his Order. In 1215, Francis may have gone to Rome for the Fourth Lateran Council, but that is not certain. During this time, he probably met a canon, Dominic de Guzman[6] (later to be Saint Dominic, the founder of the Friars Preachers, another Catholic religious order). In 1217, he offered to go to France. Cardinal Ugolino of Segni (the future Pope Gregory IX), an early and important supporter of Francis, advised him against this and said that he was still needed in Italy.

In 1219, accompanied by another friar and hoping to convert the Sultan of Egypt or win martyrdom in the attempt, Francis went to Egypt during the Fifth Crusade where a Crusader army had been encamped for over a year besieging the walled city of Damietta two miles (3.2 kilometres) upstream from the mouth of one of the main channels of the Nile. The Sultan, al-Kamil, a nephew of Saladin, had succeeded his father as Sultan of Egypt in 1218 and was encamped upstream of Damietta, unable to relieve it. A bloody and futile attack on the city was launched by the Christians on 29 August 1219, following which both sides agreed to a ceasefire which lasted four weeks.[28] It was most probably during this interlude that Francis and his companion crossed the Muslims' lines and were brought before the Sultan, remaining in his camp for a few days.[29] The visit is reported in contemporary Crusader sources and in the earliest biographies of Francis, but they give no information about what transpired during the encounter beyond noting that the Sultan received Francis graciously and that Francis preached to the Muslims without effect, returning unharmed to the Crusader camp.[30] No contemporary Arab source mentions the visit.[31] One detail, added by Bonaventure in the official life of Francis (written forty years after the event), has Francis offering to challenge the Sultan's "priests" to trial-by-fire in order to prove the veracity of the Christian Gospel.

Such an incident is alluded to in a scene in the late 13th-century fresco cycle, attributed to Giotto, in the upper basilica at Assisi.[32] It has been suggested that the winged figures atop the columns piercing the roof of the building on the left of the scene are not idols (as Erwin Panofsky had proposed) but are part of the secular iconography of the sultan, affirming his worldly power which, as the scene demonstrates, is limited even as regards his own "priests" who shun the challenge.[33][34] Although Bonaventure asserts that the sultan refused to permit the challenge, subsequent biographies went further, claiming that a fire was actually kindled which Francis unhesitatingly entered without suffering burns. The scene in the fresco adopts a position midway between the two extremes. Since the idea was put forward by the German art historian, Friedrich Rintelen in 1912,[35] many scholars have expressed doubt that Giotto was the author of the Upper Church frescoes.

According to some late sources, the Sultan gave Francis permission to visit the sacred places in the Holy Land and even to preach there. All that can safely be asserted is that Francis and his companion left the Crusader camp for Acre, from where they embarked for Italy in the latter half of 1220. Drawing on a 1267 sermon by Bonaventure, later sources report that the Sultan secretly converted or accepted a death-bed baptism as a result of the encounter with Francis.[36] The Franciscan Order has been present in the Holy Land almost uninterruptedly since 1217 when Brother Elias arrived at Acre. It received concessions from the Mameluke Sultan in 1333 with regard to certain Holy Places in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, and (so far as concerns the Catholic Church) jurisdictional privileges from Pope Clement VI in 1342.[37]

Reorganization of the Franciscan Order

By this time, the growing Order of friars was divided into provinces and groups were sent to France, Germany, Hungary, and Spain and to the East. Upon receiving a report of the martyrdom of five brothers in Morocco, Francis returned to Italy via Venice.[38] Cardinal Ugolino di Conti was then nominated by the Pope as the protector of the Order. Another reason for Francis' return to Italy was that the Franciscan Order had grown at an unprecedented rate compared to previous religious orders, but its organizational sophistication had not kept up with this growth and had little more to govern it than Francis' example and simple rule. To address this problem, Francis prepared a new and more detailed Rule, the "First Rule" or "Rule Without a Papal Bull" (Regula prima, Regula non bullata), which again asserted devotion to poverty and the apostolic life. However, it also introduced greater institutional structure, though this was never officially endorsed by the pope.[3]

On 29 September 1220, Francis handed over the governance of the Order to Brother Peter Catani at the Porziuncola, but Brother Peter died only five months later, on 10 March 1221, and was buried there. When numerous miracles were attributed to the deceased brother, people started to flock to the Porziuncola, disturbing the daily life of the Franciscans. Francis then prayed, asking Peter to stop the miracles and to obey in death as he had obeyed during his life.

.jpg)

The reports of miracles ceased. Brother Peter was succeeded by Brother Elias as Vicar of Francis. Two years later, Francis modified the "First Rule", creating the "Second Rule" or "Rule With a Bull", which was approved by Pope Honorius III on 29 November 1223. As the official Rule of the Order, it called on the friars "to observe the Holy Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ, living in obedience without anything of our own and in chastity". In addition, it set regulations for discipline, preaching, and entry into the Order. Once the Rule was endorsed by the Pope, Francis withdrew increasingly from external affairs.[3] During 1221 and 1222, Francis crossed Italy, first as far south as Catania in Sicily and afterward as far north as Bologna.

Stigmata, final days, and Sainthood

While he was praying on the mountain of Verna, during a forty-day fast in preparation for Michaelmas (29 September), Francis is said to have had a vision on or about 14 September 1224, the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, as a result of which he received the stigmata. Brother Leo, who had been with Francis at the time, left a clear and simple account of the event, the first definite account of the phenomenon of stigmata. "Suddenly he saw a vision of a seraph, a six-winged angel on a cross. This angel gave him the gift of the five wounds of Christ."[41] Suffering from these stigmata and from trachoma, Francis received care in several cities (Siena, Cortona, Nocera) to no avail. In the end, he was brought back to a hut next to the Porziuncola. Here, in the place where the Franciscan movement began, and feeling that the end of his life was approaching, he spent his last days dictating his spiritual testament. He died on the evening of Saturday, 3 October 1226, singing Psalm 142 (141), "Voce mea ad Dominum".

On 16 July 1228, he was pronounced a saint by Pope Gregory IX (the former cardinal Ugolino di Conti, a friend of Saint Francis and Cardinal Protector of the Order). The next day, the Pope laid the foundation stone for the Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi. Francis was buried on 25 May 1230, under the Lower Basilica, but his tomb was soon hidden on orders of Brother Elias to protect it from Saracen invaders. His exact burial place remained unknown until it was re-discovered in 1818. Pasquale Belli then constructed for the remains a crypt in neo-classical style in the Lower Basilica. It was refashioned between 1927 and 1930 into its present form by Ugo Tarchi, stripping the wall of its marble decorations. In 1978, the remains of Saint Francis were examined and confirmed by a commission of scholars appointed by Pope Paul VI, and put into a glass urn in the ancient stone tomb.

Character and legacy

Francis set out to imitate Christ and literally carry out his work. This is important in understanding Francis' character, his affinity for the Eucharist and respect for the priests who carried out the sacrament.[3] He preached: "Your God is of your flesh, He lives in your nearest neighbor, in every man."[42]

He and his followers celebrated and even venerated poverty, which was so central to his character that in his last written work, the Testament, he said that absolute personal and corporate poverty was the essential lifestyle for the members of his order.[3]

He believed that nature itself was the mirror of God. He called all creatures his "brothers" and "sisters", and even preached to the birds[43][44] and supposedly persuaded a wolf in Gubbio to stop attacking some locals if they agreed to feed the wolf. In his Canticle of the Creatures ("Praises of Creatures" or "Canticle of the Sun"), he mentioned the "Brother Sun" and "Sister Moon", the wind and water. His deep sense of brotherhood under God embraced others, and he declared that "he considered himself no friend of Christ if he did not cherish those for whom Christ died".[3]

Francis' visit to Egypt and attempted rapprochement with the Muslim world had far-reaching consequences, long past his own death, since after the fall of the Crusader Kingdom, it would be the Franciscans, of all Catholics, who would be allowed to stay on in the Holy Land and be recognized as "Custodians of the Holy Land" on behalf of the Catholic Church.

At Greccio near Assisi, around 1220, Francis celebrated Christmas by setting up the first known presepio or crèche (Nativity scene).[45] His nativity imagery reflected the scene in traditional paintings. He used real animals to create a living scene so that the worshipers could contemplate the birth of the child Jesus in a direct way, making use of the senses, especially sight.[45] Both Thomas of Celano and Saint Bonaventure, biographers of Saint Francis, tell how he used only a straw-filled manger (feeding trough) set between a real ox and donkey.[45] According to Thomas, it was beautiful in its simplicity, with the manger acting as the altar for the Christmas Mass.

Nature and the environment

Francis preached the Christian doctrine that the world was created good and beautiful by God but suffers a need for redemption because of human sin. As someone who saw God reflected in nature, "St. Francis was a great lover of God's creation,..."[46] In the Canticle of the Sun he gives God thanks for Brother Sun, Sister Moon, Brother Wind, Water, Fire, and Earth, all of which he sees as rendering praise to God.[47]

Many of the stories that surround the life of Saint Francis say that he had a great love for animals and the environment.[43] The "Fioretti" ("Little Flowers"), is a collection of legends and folklore that sprang up after the Saint's death. One account describes how one day, while Francis was traveling with some companions, they happened upon a place in the road where birds filled the trees on either side. Francis told his companions to "wait for me while I go to preach to my sisters the birds."[43] The birds surrounded him, intrigued by the power of his voice, and not one of them flew away. He is often portrayed with a bird, typically in his hand.

Another legend from the Fioretti tells that in the city of Gubbio, where Francis lived for some time, was a wolf "terrifying and ferocious, who devoured men as well as animals". Francis went up into the hills and when he found the wolf, he made the sign of the cross and commanded the wolf to come to him and hurt no one. Then Francis led the wolf into the town, and surrounded by startled citizens made a pact between them and the wolf. Because the wolf had “done evil out of hunger, the townsfolk were to feed the wolf regularly. In return, the wolf would no longer prey upon them or their flocks. In this manner Gubbio was freed from the menace of the predator.[48]

On 29 November 1979, Pope John Paul II declared Saint Francis the Patron Saint of Ecology.[49] On 28 March 1982, John Paul II said that Saint Francis' love and care for creation was a challenge for contemporary Catholics and a reminder "not to behave like dissident predators where nature is concerned, but to assume responsibility for it, taking all care so that everything stays healthy and integrated, so as to offer a welcoming and friendly environment even to those who succeed us."[50] The same Pope wrote on the occasion of the World Day of Peace, 1 January 1990, the saint of Assisi "offers Christians an example of genuine and deep respect for the integrity of creation ..." He went on to make the point that: "As a friend of the poor who was loved by God's creatures, Saint Francis invited all of creation – animals, plants, natural forces, even Brother Sun and Sister Moon – to give honor and praise to the Lord. The poor man of Assisi gives us striking witness that when we are at peace with God we are better able to devote ourselves to building up that peace with all creation which is inseparable from peace among all peoples."[51]

It is a popular practice on his feastday, October 4, for people to bring their pets and other animals to church for a blessing.[52]

Feast day

Saint Francis' feast day is observed on 4 October. A secondary feast in honor of the stigmata received by Saint Francis, celebrated on 17 September, was inserted in the General Roman Calendar in 1585 (later than the Tridentine Calendar) and suppressed in 1604, but was restored in 1615. In the New Roman Missal of 1969, it was removed again from the General Calendar, as something of a duplication of the main feast on 4 October, and left to the calendars of certain localities and of the Franciscan Order.[53] Wherever the traditional Roman Missal is used, however, the feast of the Stigmata remains in the General Calendar.

Saint Francis is honored in the Church of England, the Anglican Church of Canada, the Episcopal Church USA, the Old Catholic Churches, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, and other churches and religious communities on 4 October.

Papal name

On 13 March 2013, upon his election as Pope, Archbishop and Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina chose Francis as his papal name in honor of Saint Francis of Assisi, becoming Pope Francis.[54]

At his first audience on 16 March 2013, Pope Francis told journalists that he had chosen the name in honor of Saint Francis of Assisi, and had done so because he was especially concerned for the well-being of the poor.[55][56][57] He explained that, as it was becoming clear during the conclave voting that he would be elected the new bishop of Rome, the Brazilian Cardinal Cláudio Hummes had embraced him and whispered, "Don't forget the poor", which had made Bergoglio think of the saint.[58][59] Bergoglio had previously expressed his admiration for St. Francis, explaining that “He brought to Christianity an idea of poverty against the luxury, pride, vanity of the civil and ecclesiastical powers of the time. He changed history."[60] Bergoglio's selection of his papal name is the first time that a pope has been named Francis.[lower-alpha 1]

Patronage

_-_St._Francis_of_Assisi_relic.jpg)

On 18 June 1939, Pope Pius XII named Francis a joint Patron Saint of Italy along with Saint Catherine of Siena with the apostolic letter "Licet Commissa".[62] Pope Pius also mentioned the two saints in the laudative discourse he pronounced on 5 May 1949, in the Church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva.

St. Francis is the patron of animals, merchants, and ecology.[7] He is also considered the patron saint against dying alone; patron saint against fire; patron saint of the Franciscan Order and Catholic Action; patron saint of families, peace, and needleworkers. He is the patron saint of many dioceses and other locations around the world, including: Italy; San Pawl il-Bahar, Malta; Freising, Germany; Lancaster, England; Kottapuram, India; San Francisco de Malabon, Philippines (General Trias City); San Francisco, California; Santa Fe, New Mexico; Colorado; Salina, Kansas; Metuchen, New Jersey; and Quibdó, Colombia.[63]

Outside Catholicism

Protestantism

Emerging since the 19th century, there are several Protestant adherents and groups, sometimes organized as religious orders, which strive to adhere to the teachings and spiritual disciplines of Saint Francis.

The 20th-century High Church Movement gave birth to Franciscan-inspired orders among the revival of religious orders in Protestant Christianity.

One of the results of the Oxford Movement in the Anglican Church during the 19th century was the re-establishment of religious orders, including some of Franciscan inspiration. The principal Anglican communities in the Franciscan tradition are the Community of St. Francis (women, founded 1905), the Poor Clares of Reparation (P.C.R.), the Society of Saint Francis (men, founded 1934), and the Community of St. Clare (women, enclosed).

A U.S.-founded order within the Anglican world communion is the Seattle-founded order of Clares in Seattle (Diocese of Olympia), The Little Sisters of St. Clare.[64]

There are also some small Franciscan communities within European Protestantism and the Old Catholic Church. There are some Franciscan orders in Lutheran Churches,[65] including the Order of Lutheran Franciscans, the Evangelical Sisterhood of Mary, and the Evangelische Kanaan Franziskus-Bruderschaft (Kanaan Franciscan Brothers). In addition, there are associations of Franciscan inspiration not connected with a mainstream Christian tradition and describing themselves as ecumenical or dispersed.

The Anglican church retained the Catholic tradition of blessing animals on or near Francis' feast day of 4 October, and more recently Lutheran and other Protestant churches have adopted the practice.[66]

Orthodox churches

St Francis' feast is celebrated at New Skete, an Orthodox Christian monastic community in Cambridge, New York.[67]

Other faiths

Outside of Christianity, other individuals and movements are influenced by the example and teachings of Saint Francis. These include the popular philosopher Eckhart Tolle, who has made videos on the spirituality of Saint Francis.[68]

The interfaith spiritual community of Skanda Vale also takes inspiration from the example of Saint Francis, and models itself as an interfaith Franciscan order.[69]

St Francis' Way

In 2019, the Umbria tourist board was continuing the process of refurbishing the route from Florence to Rome that Francis is believed to have used. Called the Via di Francesco or Cammino di Francesco, the 550 kilometer St Francis Way "pilgrimage route" is intended for travel on foot or by bicycle.[70][71][72]

Main writings

- Canticum Fratris Solis or Laudes Creaturarum; Canticle of the Sun.

- Prayer before the Crucifix, 1205 (extant in the original Umbrian dialect as well as in a contemporary Latin translation);

- Regula non bullata, the Earlier Rule, 1221;

- Regula bullata, the Later Rule, 1223;

- Testament, 1226;

- Admonitions.

For a complete list, see The Franciscan Experience.[73]

Saint Francis is considered the first Italian poet by literary critics.[74] He believed commoners should be able to pray to God in their own language, and he wrote often in the dialect of Umbria instead of Latin. His writings are considered to have great literary and religious value.[75]

The anonymous 20th-century prayer "Make Me an Instrument of Your Peace" is widely but erroneously attributed to Saint Francis.[76][77]

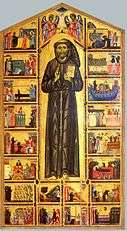

In art

The Franciscan Order promoted devotion to the life of Saint Francis from his canonization onwards. The order commissioned many works for Franciscan churches, either showing Saint Francis with sacred figures, or episodes from his life. There are large early fresco cycles in the Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi, parts of which are shown above.

- Francis of Assisi in art

St. Francis and scenes from his life, 13th century

St. Francis and scenes from his life, 13th century

_-_WGA06432.jpg) The Stigmatization of St Francis, Domenico Veneziano, 1445

The Stigmatization of St Francis, Domenico Veneziano, 1445

Saint Francis with the Blood of Christ, Carlo Crivelli, c. 1500

Saint Francis with the Blood of Christ, Carlo Crivelli, c. 1500 Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, Studio of El Greco, 1585–1590

Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, Studio of El Greco, 1585–1590 Francis of Assisi with angel music, Francisco Ribalta, c. 1620

Francis of Assisi with angel music, Francisco Ribalta, c. 1620 Saint Francis in Meditation, Francisco de Zurbarán, 1639

Saint Francis in Meditation, Francisco de Zurbarán, 1639 Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy, Jusepe de Ribera, 1639

Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy, Jusepe de Ribera, 1639.jpg) Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy, Caravaggio, c. 1595

Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy, Caravaggio, c. 1595 Francis of Assisi visiting his convent while far away, in a chariot of fire, José Benlliure y Gil (1855–1937)

Francis of Assisi visiting his convent while far away, in a chariot of fire, José Benlliure y Gil (1855–1937) The Ecstasy of St. Francis, Stefano di Giovanni, 1444

The Ecstasy of St. Francis, Stefano di Giovanni, 1444 Nazario Gerardi as St. Francis in The Flowers of St. Francis, 1950

Nazario Gerardi as St. Francis in The Flowers of St. Francis, 1950 Statue in Askeaton Abbey, Ireland, claimed to cure toothache, 14th–15th century

Statue in Askeaton Abbey, Ireland, claimed to cure toothache, 14th–15th century

Media

Films

- The Flowers of St. Francis, a 1950 film directed by Roberto Rossellini and co-written by Federico Fellini

- Francis of Assisi, a 1961 film directed by Michael Curtiz, based on the novel The Joyful Beggar by Louis de Wohl

- Francis of Assisi, a 1966 film directed by Liliana Cavani

- Uccellacci e uccellini (The Hawks and the Sparrows), a 1966 film directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini

- Brother Sun, Sister Moon, a 1972 film by Franco Zeffirelli

- Francesco, a 1989 film by Liliana Cavani, contemplatively paced, follows Francis of Assisi's evolution from rich man's son to religious humanitarian, and eventually to a full-fledged self-tortured saint. Saint Francis is played by Mickey Rourke, and the woman who later became Saint Clare, is played by Helena Bonham Carter

- St. Francis, a 2002 film directed by Michele Soavi, starring Raoul Bova and Amélie Daure

- Clare and Francis, a 2007 film directed by Fabrizio Costa, starring Mary Petruolo and Ettore Bassi

- Pranchiyettan and the Saint, a 2010 satirical Indian Malayalam film

- Finding Saint Francis, a 2014 film directed by Paul Alexander

- L'ami – François d'Assise et ses frères, a 2016 film directed by Renaud Fely and Arnaud Louvet, starring Elio Germano

- The Sultan and the Saint, a 2016 film directed by Alexander Kronemer, starring Alexander McPherson

- In Search of Saint Francis of Assisi,[78] documentary featuring Franciscan monks and others

Music

- Franz Liszt:

- Cantico del sol di Francesco d'Assisi, S.4 (sacred choral work, 1862, 1880–81; versions of the Prelude for piano, S. 498c, 499, 499a; version of the Prelude for organ, S. 665, 760; version of the Hosannah for organ and bass trombone, S.677)

- St. François d'Assise: La Prédication aux oiseaux, No. 1 of Deux Légendes, S.175 (piano, 1862–63)

- William Henry Draper: All Creatures of Our God and King (hymn paraphrase of Canticle of the Sun, published 1919)

- Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Fioretti (voice and orchestra, 1920)

- Gian Francesco Malipiero: San Francesco d'Assisi (soloists, chorus and orchestra, 1920–21)

- Hermann Suter: Le Laudi (The Praises) or Le Laudi di San Francesco d'Assisi, based on the Canticle of the Sun, (oratorio, 1923)

- Amy Beach: Canticle of the Sun (soloists, chorus and orchestra, 1928)

- Paul Hindemith: Nobilissima Visione (ballet 1938)

- Leo Sowerby: Canticle of the Sun (cantata for mixed voices with accompaniment for piano or orchestra, 1944)

- Francis Poulenc: Quatre petites prières de saint François d’Assise (men's chorus, 1948)

- Seth Bingham: The Canticle of the Sun (cantata for chorus of mixed voices with soli ad lib. and accompaniment for organ or orchestra, 1949)

- William Walton: Cantico del sol (chorus, 1973–74)

- Olivier Messiaen: Saint François d'Assise (opera, 1975–83)

- Juliusz Łuciuk: Święty Franciszek z Asyżu (oratorio for soprano, tenor, baritone, mixed chorus and orchestra, 1976)

- Peter Janssens: Franz von Assisi, Musikspiel (Musical play, text: Wilhelm Wilms, 1978)

- Michele Paulicelli: Forza venite gente (musical theater, 1981)

- Karlheinz Stockhausen: Luzifers Abschied (1982), scene 4 of the opera Samstag aus Licht

- Libby Larsen: I Will Sing and Raise a Psalm (SATB chorus and organ, 1995)

- Sofia Gubaidulina: Sonnengesang (solo cello, chamber choir and percussion, 1997)

- Juventude Franciscana: Balada de Francisco (voices accompanied by guitar, 1999)

- Angelo Branduardi : L'infinitamente piccolo (album, 2000)

- Lewis Nielson: St. Francis Preaches to the Birds (chamber concerto for violin, 2005)

- Peter Reulein (composer) / Helmut Schlegel (libretto): Laudato si' (oratorio, 2016)

Books

- Francis of Assisi, The Little Flowers (Fioretti), London, 2012. limovia.net ISBN 978-1-78336-013-0

- Saint Francis of Assisi, written and illustrated by Demi, Wisdom Tales, 2012, ISBN 978-1-937786-04-5

- Francis of Assisi: A New Biography, by Augustine Thompson, O.P., Cornell University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-080145-070-9

- Francis of Assisi in the Sources and Writings, by Robert Rusconi and translated by Nancy Celaschi, Franciscan Institute Publications, 2008. ISBN 978-1-57659-152-9

- The Complete Francis of Assisi: His Life, The Complete Writings, and The Little Flowers, ed. and trans. Jon M. Sweeney, Paraclete Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1-61261-688-9

- The Stigmata of Francis of Assisi, Franciscan Institute Publications, 2006. ISBN 978-1-57659-140-6

- Francis of Assisi – The Message in His Writings, by Thaddee Matura, Franciscan Institute Publications, 1997. ISBN 978-1-57659-127-7

- Saint Francis of Assisi, by John R. H. Moorman, Franciscan Institute Publications, 1987. ISBN 978-0-8199-0904-6

- First Encounter with Francis of Assisi, by Damien Vorreux and translated by Paul LaChance, Franciscan Institute Publications, 1979. ISBN 978-0-8199-0698-4

- St. Francis of Assisi, by Raoul Manselli, Franciscan Institute Publications, 1985. ISBN 978-0-8199-0880-3

- Saint Francis of Assisi, by Thomas of Celano and translated by Placid Hermann, Franciscan Institute Publications, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8199-0554-3

- Francis the Incomparable Saint, by Joseph Lortz, Franciscan Institute Publications, 1986, ISBN 978-1-57659-067-6

- Respectfully Yours: Signed and Sealed, Francis of Assisi, by Edith van den Goorbergh and Theodore Zweerman, Franciscan Institute Publications, 2001. ISBN 978-1-57659-178-9

- The Admonitions of St. Francis: Sources and Meanings, by Robert J. Karris, Franciscan Institute Publications, 1999. ISBN 978-1-57659-166-6

- We Saw Brother Francis, by Francis de Beer, Franciscan Institute Publications, 1983. ISBN 978-0-8199-0803-2

- Sant Francesc (Saint Francis, 1895), a book of forty-three Saint Francis poems by Catalan poet-priest Jacint Verdaguer, three of which are included in English translation in Selected Poems of Jacint Verdaguer: A Bilingual Edition, edited and translated by Ronald Puppo, with an introduction by Ramon Pinyol i Torrents (University of Chicago, 2007). The three poems are "The Turtledoves", "Preaching to Birds" and "The Pilgrim".

- Saint Francis of Assisi (1923), a book by G. K. Chesterton

- Blessed Are The Meek (1944). a book by Zofia Kossak

- Saint Francis of Assisi a Doubleday Image Book translated by T. O'Conor Sloane, Ph.D., LL.D. in 1955 from the Danish original researched and written by Johannes Jorgensen and published in 1912 by Longmans, Green and Company, Inc.

- Saint Francis of Assisi (God's Pauper) (1962), a novel by Nikos Kazantzakis

- Scripta Leonis, Rufini Et Angeli Sociorum S. Francisci: The Writings of Leo, Rufino and Angelo Companions of St. Francis (1970), edited by Rosalind B. Brooke, in Latin and English, containing testimony recorded by intimate, long-time companions of Saint Francis

- Saint Francis and His Four Ladies (1970), a book by Joan Mowat Erikson

- The Life and Words of St. Francis of Assisi (1973), by Ira Peck

- The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi (1996), a book by Patricia Stewart

- Reluctant Saint: The Life of Francis of Assisi (2002), a book by Donald Spoto

- Flowers for St. Francis (2005), a book by Raj Arumugam

- Chasing Francis, 2006, a book by Ian Cron

- John Tolan, St. Francis and the Sultan: The Curious History of a Christian-Muslim Encounter. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Vita di un uomo: Francesco d'Assisi (1995) a book by Chiara Frugoni, preface by Jacques Le Goff, Torino: Einaudi.

- Francis, Brother of the Universe (1982), a 48-page comic book by Marvel Comics on the life of Saint Francis of Assisi written by Father Roy Gasnik O.F.M. and Mary Jo Duffy, artwork by John Buscema and Marie Severin, lettering by Jim Novak and edited by Jim Shooter.

Other

| Part of a series on |

| Eucharistic adoration of the Catholic Church |

|---|

Solar monstrance of the Eucharist |

| Papal documents |

| Organisations and events |

|

| Notable individuals |

| Eucharistic meditators |

|

|

|

- In Rubén Darío's poem Los Motivos Del Lobo (The Reasons Of The Wolf) St. Francis tames a terrible wolf only to discover that the human heart harbors darker desires than those of the beast.

- In Fyodor Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov, Ivan Karamazov invokes the name of 'Pater Seraphicus,' an epithet applied to St. Francis, to describe Alyosha's spiritual guide Zosima. The reference is found in Goethe's "Faust", Part 2, Act 5, lines 11918–25.[79]

- In Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, Henry Adams' chapter on the "Mystics" discusses Francis extensively.

- Francesco's Friendly World was a 1996–97 direct-to-video Christian animated series produced by Lyrick Studios that was about Francesco and his talking animal friends as they rebuild the Church of San Damiano.[80]

- Rich Mullins co-wrote Canticle of the Plains, a musical, with Mitch McVicker. Released in 1997, it was based on the life of Saint Francis of Assisi, but told as a western story.

- Bernard Malamud's novel The Assistant (1957) features a protagonist, Frank Alpine, who exemplifies the life of Saint Francis in mid-20th-century Brooklyn, New York City.

See also

- Pardon of Assisi

- Fraticelli

- Society of Saint Francis

- Saint Juniper, one of Francis' original followers

- St. Benedict's Cave, which contains a portrait of Francis made during his lifetime

- Saint-François d'Assise, an opera by Olivier Messiaen

- Saint-François (disambiguation) (places named after Francis of Assisi in French-speaking countries)

- List of places named after Saint Francis

- Saint Francis of Assisi, patron saint archive

- Blessing of animals

- Prayers

- Canticle of the Sun, a prayer by Saint Francis

- Prayer of Saint Francis, a prayer often misattributed to Saint Francis

Notes

References

- Brooke, Rosalind B. The Image of St Francis: Responses to Sainthood in the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 161–62.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Brady, Ignatius Charles. "Saint Francis of Assisi." Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- "Holy Men and Holy Women" (PDF). Churchofengland.org.

- "Notable Lutheran Saints". Resurrectionpeople.org.

- Chesterton (1924), p.126

- "Saint Francis of Assisi". Franciscan Media. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Ilia Delio. "Francis of Assisi, nature's mystic". The Washington Post, March 20, 2013.

- Tolan, John (2009). St. Francis and the Sultan: The Curious History of a Christian-Muslim Encounter. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199239726.

- "St. Francis of Assisi – Franciscan Friars of the Renewal". Franciscanfriars.com. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- The Christmas scenes made by Saint Francis at the time were not inanimate objects, but live ones, later commercialised into inanimate representations of the Blessed Lord and His parents.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Cross, F. L., ed. (2005). "Francis of Assisi". The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199566712.

- Cross, F. L., ed. (2005). "Stigmatization". The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199566712.

- Englebert, Omer (1951). The Lives of the Saints. New York: Barnes & Noble. p. 529. ISBN 978-1-56619-516-4.

- Dagger, Jacob (November–December 2006). "Blessing All Creatures, Great and Small". Duke Magazine. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Chesterton, Gilbert Keith (1924). "St. Francis of Assisi" (14 ed.). Garden City, New York: Image Books: 158. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Chesterton (1924), pp. 40–41

- Chesterton (1924), pp. 54–56

- de la Riva, Fr. John (2011). "Life of St. Francis". St. Francis of Assisi National Shrine. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Kiefer, James E. (1999). "Francis of Assisi, Friar". Biographical sketches of memorable Christians of the past. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Chesterton (1924), pp. 107–108

- Galli(2002), pp. 74–80

- Chesterton (1924), pp. 110–111

- Fioretti quoted in: St. Francis, The Little Flowers, Legends, and Lauds, trans. N. Wydenbruck, ed. Otto Karrer (London: Sheed and Ward, 1979) 244.

- Chesterton (1924), p.130

- Runciman, Steven. History of the Crusades, vol. 3: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades, Cambridge University Press (1951, paperback 1987), pp. 151–161.

- Tolan, pp. 4f.

- e.g., Jacques de Vitry, Letter 6 of February or March 1220 and Historia orientalis (c. 1223–1225) cap. XXII; Tommaso da Celano, Vita prima (1228), §57: the relevant passages are quoted in an English translation in Tolan, pp. 19f. and 54 respectively.

- Tolan, p.5

- e.g., Chesterton, Saint Francis, Hodder & Stoughton (1924) chapter 8. Tolan (p.126) discusses the incident as recounted by Bonaventure, an incident which does not extend to a fire actually being lit.

- Péter Bokody, "Idolatry or Power: St. Francis in Front of the Sultan", in: Promoting the Saints: Cults and Their Contexts from Late Antiquity until the Early Modern Period, ed. Ottó Gecser and others (Budapest: CEU Press, 2010), 69–81, esp. at pp. 74 and 76–78. The views of Panofsky (idols: see Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art, New York 1972, p.148, n.3) and Tolan (undecided: p.143) are cited at p.73.

- Bonaventure, Legenda major (1260–1263), cap. IX §7–9, criticized by, e.g., Sabatier, La Vie de St. François d'Assise (1894), chapter 13, and Paul Moses, The Saint and the Sultan: The Crusades, Islam, and Francis of Assisi's Mission of Peace, Doubleday Religion (2009) excerpted in a restricted-view article in Commonwealth magazine, 25 September 2009 "Mission improbable: St. Francis & the Sultan", accessed 4 April 2015

- Friedrich Rintelen, Giotto und die Giotto-apokryphen, (1912)

- For grants of various permissions and privileges to Francis as attributed by later sources, see, e.g., Tolan, pp. 258–263. The first mention of the Sultan's conversion occurs in a sermon delivered by Bonaventure on 4 October 1267. See Tolan, pp. 168

- Bulla Gratias agimus, commemorated by Pope John Paul II in a Letter dated 30 November 1992. See also Tolan, p.258. On the Franciscan presence, including an historical overview, see, generally the official website at Custodia and Custodian of the Holy Land

- Bonaventure (1867), p. 162

- Le Goff, Jacques. Saint Francis of Assisi, 2003 ISBN 0-415-28473-2 page 44

- Miles, Margaret Ruth. The Word made flesh: a history of Christian thought, 2004 ISBN 978-1-4051-0846-1 pages 160–161

- Chesterton (1924), p.131

- Eimerl, Sarel (1967). The World of Giotto: c. 1267–1337. et al. Time-Life Books. p. 15. ISBN 0-900658-15-0.

- Bonaventure (1867), pp. 78–85

- Ugolino Brunforte (Brother Ugolino) (1958). The Little Flowers of St. Francis of Assisi. Calvin College: CCEL. ISBN 978-1-61025212-6.

Quote.

- Bonaventure (1867), p. 178

- Warner OFM, Keith (April 2010). "St. Francis: Patron of ecology". U.S. Catholic. 75 (4): 25.

- Doyle, Eric (1996). St. Francis and the Song of Brotherhood and Sisterhood. Franciscan Institute. ISBN 978-1576590034.

- Hudleston, Roger, ed. (1926). The Little Flowers of Saint Francis. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- Pope John Paul II (29 November 1979). "Inter Sanctos (Apostolic Letter AAS 71)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Pope John Paul II (28 March 1982). "Angelus". Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Pope John Paul II (8 December 1989). "World Day of Peace 1990". Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Pappas, William. "The Patron Saint of Animals and Ecology", Earthday.org, October 6, 2016

- Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana), p. 139

- Pope Francis (16 March 2013). "Audience to Representatives of the Communications Media". Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- "Pope Francis explains decision to take St Francis of Assisi's name". The Guardian. London. 16 March 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013.

- "New Pope Fra[n]cis visits St. Mary Major, collects suitcases and pays bill at hotel". News.va. 14 March 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Michael Martinez, CNN Vatican analyst: Pope Francis' name choice 'precedent shattering', CNN (13 March 2013). Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- Laura Smith-Spark et al. : Pope Francis explains name, calls for church 'for the poor' CNN,16 March 2013

- "Pope Francis wants 'poor Church for the poor'". BBC News. BBC. 16 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- Bethune, Brian, "Pope Francis: How the first New World pontiff could save the church", macleans.ca, 26 March 2013, Retrieved 27 March 2013

- Alpert, Emily (13 March 2013). "Vatican: It's Pope Francis, not Pope Francis I". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 March 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Pope Pius XII (18 June 1939). "Licet Commissa" (Apostolic Letter AAS 31, pp. 256–257)

- Beverly Johnson Roberts, "St. Francis Patron". Archived 21 March 2009.

- "The Little Sisters of St. Clare". Archived from the original on 2010-09-02. Retrieved 2019-04-16.

- "Order of Lutheran Franciscans". Lutheranfranciscans.org. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Bliss, Peggy Ann (3 October 2019). "Animals to be blessed Saturday at Episcopal Cathedral" (PDF). The San Juan Daily Star. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- "Events, New Skete Monastery". newskete.org.

- "St Francis of Assisi - What is Perfect Joy!". Eckhart Tolle Now. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Skanda Vale - Frequently asked questions". Skanda Vale. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- "Walking in Italy: on the trail of Saint Francis of Assisi". The Guardian. 3 November 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- "St Francis' Way". Via di Francesco. 6 June 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

intends to reintroduce the Franciscan experience in the lands that the Poor Man walked through on his travels.

- "St Francis Way in Italy". Camino Ways. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- "Writings of St. Francis – Part 2". Archived from the original on 2013-01-28. Retrieved 2013-01-17.

- Brand, Peter; Pertile, Lino, eds. (1999). "2 – Poetry. Francis of Assisi (pp. 5ff.)". The Cambridge History of Italian Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52166622-0. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Chesterton, G.K. (1987). St. Francis. Image. pp. 160 p. ISBN 0-385-02900-4. Archived from the original on 12 August 2013.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Renoux, Christian (2001). La prière pour la paix attribuée à saint François: une énigme à résoudre. Paris: Editions franciscaines. ISBN 2-85020-096-4.

- Renoux, Christian. "The Origin of the Peace Prayer of St. Francis". Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- In Search of Saint Francis of Assisi, Green Apple Entertainment. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Медведев, Александр (2015). ""Сердце милующее": образы праведников в творчестве Ф. М. Достоевского и св. Франциск Ассизский". Известия Уральского федерального университета. Серия 2: Гуманитарные науки. №2 (139): 222–233. Retrieved 11 July 2019 – via www.academia.edu.

- "Mark Bernthal - TV-VIDEOS". www.markbernthal.com.

Bibliography

- Scripta Leonis, Rufini et Angeli Sociorum S. Francisci: The Writings of Leo, Rufino and Angelo Companions of St. Francis, original manuscript, 1246, compiled by Brother Leo and other companions (1970, 1990, reprinted with corrections), Oxford, Oxford University Press, edited by Rosalind B. Brooke, in Latin and English, ISBN 0-19-822214-9, containing testimony recorded by intimate, long-time companions of St. Francis

- Francis of Assisi, The Little Flowers (Fioretti), London, 2012. limovia.net ISBN 978-1-78336-013-0

- Bonaventure; Cardinal Manning (1867). The Life of St. Francis of Assisi (from the Legenda Sancti Francisci) (1988 ed.). Rockford, Illinois: TAN Books & Publishers. ISBN 978-0-89555-343-0

- Chesterton, Gilbert Keith (1924). St. Francis of Assisi (14 ed.). Garden City, New York: Image Books.

- Englebert, Omer (1951). The Lives of the Saints. New York: Barnes & Noble.

- Karrer, Otto, ed., St. Francis, The Little Flowers, Legends, and Lauds, trans. N. Wydenbruck, (London: Sheed and Ward, 1979)

- Tolan, John (2009). Saint Francis and the Sultan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- Acocella, Joan (14 January 2013). "Rich Man, Poor Man: The Radical Visions of St. Francis". The New Yorker. 88 (43). p. 72–77. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- Antony, Manjiyil. Assisiyile Francis. Alwaye, Santhome Creations, 2013.

- Fioretti di San Francesco, the "Little Flowers of St. Francis", end of the 14th century: an anonymous Italian version of the Actus; the most popular of the sources, but very late and therefore not the best authority by any means.

- Friar Julian of Speyer, Vita Sancti Francisci, 1232–1239.

- Friar Tommaso da Celano: Vita Prima Sancti Francisci, 1228; Vita Secunda Sancti Francisci, 1246–1247; Tractatus de Miraculis Sancti Francisci, 1252–1253.

- Friar Elias, Epistola Encyclica de Transitu Sancti Francisci, 1226.

- Pope Gregory IX, Bulla "Mira circa nos" for the canonization of St. Francis, 19 July 1228.

- St. Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, Legenda Maior Sancti Francisci, 1260–1263.

- The Little Flowers of Saint Francis (Translated by Raphael Brown), Doubleday, 1998. ISBN 978-0-385-07544-2

- Ugolino da Montegiorgio, Actus Beati Francisci et sociorum eius, 1327–1342.

External links

- "Saint Francis of Assisi", Encyclopædia Britannica online

- "St. Francis of Assisium, Confessor", Butler's Lives of the Saints

- The Franciscan Archive

- Saint Francis of Assisi – Catholic Saints & Angels

- Here Followeth the Life of Saint Francis from Caxton's translation of the Golden Legend

- Colonnade Statue in St Peter's Square

- Founder Statue in St Peter's Basilica

- "The Poor Man of Assisi". Invisible Monastery of carity and fraternity – Christian prayer group. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018.

- Works by or about Francis of Assisi at Internet Archive

- Works by Francis of Assisi at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)