Ghassanids

The Ghassanids (Arabic: الغساسنة, romanized: al-Ghasāsinah, also Banū Ghassān "Sons of Ghassān"), also called the Jafnids,[1] were a pre-Islamic Arab tribe which founded an Arab kingdom. They emigrated from Yemen in the early 3rd century to the Levant region.[2][3] Some merged with Hellenized Christian communities,[4] converting to Christianity in the first few centuries AD, while others may have already been Christians before emigrating north to escape religious persecution.[3][5]

Ghassanids الغساسنة | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220–638 | |||||||||

Flag | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Jabiyah | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic | ||||||||

| Religion | Christianity | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 220 | ||||||||

• Annexed by Rashidun Caliphate | 638 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

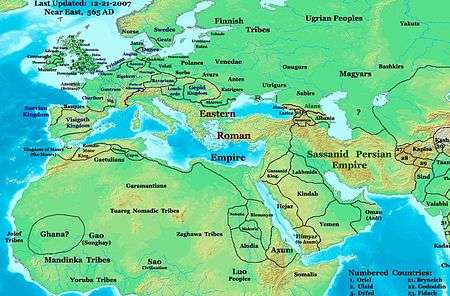

After settling in the Levant, the Ghassanids became a client state to the Byzantine Empire and fought alongside them against the Persian Sassanids and their Arab vassals, the Lakhmids.[2][5] The lands of the Ghassanids also acted as a buffer zone protecting lands that had been annexed by the Romans against raids by Bedouin tribes.

Few Ghassanids became Muslim following the Muslim conquest of the Levant; most Ghassanids remained Christian and joined Melkite and Syriac communities within what is now Jordan, Palestine, Israel, Syria and Lebanon.[3]

Migration from Yemen

According to traditional historians, the Ghassanids were part of the al-Azd tribe, and they emigrated from South Arabia, modern day Yemen. They traveled across the Arabian Peninsula and eventually settled in the Roman limes.[6][7] The tradition of Ghassanid migration finds support in the Geography of Claudius Ptolemy, which locates a tribe called the Kassanitai south of the Kinaidokolpitai and the river Baitios (probably the wādī Baysh). These are probably the people called Casani in Pliny the Elder, Gasandoi in Diodorus Siculus and Kasandreis in Photios (relying on older sources).[8][9]

The date of the migration to the Levant is unclear, but they are believed to have arrived in the region of Syria between 250-300 AD and later waves of migration circa 400 AD.[6] Their earliest appearance in records is dated to 473 AD, when their chief Amorkesos signed a treaty with the Eastern Roman Empire acknowledging their status as foederati controlling parts of Palestine. He apparently became Chalcedonian at this time. By the year 510, the Ghassanids were no longer Miaphysite, but Chalcedonian.[10] They became the leading tribe among the Arab foederati, such as Banu Amela and Banu Judham.

Ghassanid Kingdom

The "Assanite Saracen" chief Podosaces that fought alongside the Sasanians during Julian's campaign in 363 might have been a Ghassanid.[11]

Roman vassal

After originally settling in the Levant, the Ghassanids became a client state to the Eastern Roman Empire. The Romans found a powerful ally in the Ghassanids who acted as a buffer zone against the Lakhmids. In addition, as kings of their own people, they were also phylarchs, native rulers of client frontier states.[12][13] The capital was at Jabiyah in the Golan Heights. Geographically, it occupied much of the eastern Levant, and its authority extended via tribal alliances with other Azdi tribes all the way to the northern Hijaz as far south as Yathrib (Medina).[14][15]

Byzantine–Persian Wars

The Ghassanids fought alongside the Byzantine Empire against the Persian Sassanids and Arab Lakhmids.[5] The lands of the Ghassanids also continually acted as a buffer zone, protecting Byzantine lands against raids by Bedouin tribes. Among their Arab allies were the Banu Judham and Banu Amela.

The Eastern Roman Empire was focused more on the East and a long war with the Persians was always their main concern. The Ghassanids maintained their rule as the guardian of trade routes, policed Lakhmid tribes and was a source of troops for the imperial army. The Ghassanid king al-Harith ibn Jabalah (reigned 529–569) supported the Byzantines against Sassanid Persia and was given in 529 by the emperor Justinian I, the highest imperial title that was ever bestowed upon a foreign ruler; also the status of patricians.[16][17] In addition to that, al-Harith ibn Jabalah was given the rule over all the Arab allies of the Byzantine Empire.[18] Al-Harith was a Miaphysite Christian; he helped to revive the Syrian Miaphysite (Jacobite) Church and supported Miaphysite development despite Orthodox Byzantium regarding it as heretical. Later Byzantine mistrust and persecution of such religious unorthodoxy brought down his successors, al-Mundhir (reigned 569–582) and Nu'man.

The Ghassanids, who had successfully opposed the Persian allied Lakhmids of al-Hirah (Southern modern-day Iraq), prospered economically and engaged in much religious and public building; they also patronized the arts and at one time entertained the Arabian poets Nabighah adh-Dhubyani and Hassan ibn Thabit at their courts.[2]

Islamic conquest

The Ghassanids remained a Byzantine vassal state until its rulers and the eastern Byzantine Empire were overthrown by the Muslims in the 7th century, following the Battle of Yarmuk in 636 AD. At the time of the Muslim conquest the Ghassanids were no longer united by the same Christian faiths: some of them accepted union with the Byzantine Chalcedonian church; others remained faithful to Miaphysitism and a significant number of them maintained their Christian religious identity and decided to side with the Muslim armies to emphasize their loyalty to their Arabic roots and in recognition of the wider context of a rising Arab Empire under the veil of Islam. It is worth noting that a significant percentage of the Muslim armies in the Battle of Mu'tah (معركة مؤتة) were Christian Arabs. Several of those Christian Arab tribes in today's modern Jordan who sided with the Muslim armies were recognized by exempting them from paying jizya (جزية). Jizya is a form of tax paid by non-Muslims – Muslims paid another form of tax called Zakah (زكاة). Later those who remained Christian joined Melkite Syriac communities. The remnants of the Ghassanids were dispersed throughout Asia Minor.[3]

Jabalah ibn-al-Aiham's ordeal with Islam

There are different opinions why Jabalah and his followers didn't convert to Islam. Some opinions go along the general idea that the Ghassanids were not interested yet in giving up their status as the lords and nobility of Syria. Below is quoted the story of Jabalah's return to the land of the Byzantines as told by 9th-century historian al-Baladhuri.

Jabalah ibn-al-Aiham sided with the Ansar (Azdi Muslims from Medina) saying, "You are our brethren and the sons of our fathers" and professed Islam. After the arrival of 'Umar ibn-al-Khattab in Syria, year 17 (636AD), Jabalah had a dispute with one of the Muzainah and knocked out his eye. 'Umar ordered that he be punished, upon which Jabalah said, "Is his eye like mine? Never, by Allah, shall I abide in a town where I am under authority." He then apostatized and went to the land of the Greeks (the Byzantines). This Jabalah was the king of Ghassan and the successor of al-Harith ibn-abi-Shimr (or Chemor).[19]

After the fall of the first kingdom of Ghassan, King Jabalah ibn-al-Aiham established a Government-in-exile in Byzantium.[20] Ghassanid influence on the empire lasted centuries; the climax of this presence was the elevation of one of his descendants, Nikephoros I (ruled 802-811) to the throne and his establishment of a short-lived dynasty that can be described as the Nikephorian or Phocid Dynasty in the 9th century.[21] But Nikephoros was not only a mere Ghassanid descendant, he claimed the headship of the Ghassanid Dynasty using the eponym of King Jafna, the founder of the Dynasty, rather than merely express himself descendant of King Jabalah.[22][23]

Kings

Medieval Arabic authors used the term Jafnids for the Ghassanids, a term modern scholars prefer at least for the ruling stratum of Ghassanid society.[1] Earlier kings are traditional, actual dates highly uncertain.

- Jafnah I ibn ‘Amr (220–265)

- ‘Amr I ibn Jafnah (265–270)

- Tha‘labah ibn Amr (270–287)

- al-Harith I ibn Tha‘labah (287–307)

- Jabalah I ibn al-Harith I (307–317)

- al-Harith II ibn Jabalah "ibn Maria" (317–327)

- al-Mundhir I Senior ibn al-Harith II (327–330) with...

- al-Aiham ibn al-Harith II (327–330) and...

- al-Mundhir II Junior ibn al-Harith II (327–340) and...

- al-Nu'man I ibn al-Harith II (327–342) and...

- ‘Amr II ibn al-Harith II (330–356) and...

- Jabalah II ibn al-Harith II (327–361)

- Jafnah II ibn al-Mundhir I (361–391) with...

- al-Nu‘man II ibn al-Mundhir I (361–362)

- al-Nu‘man III ibn ‘Amr ibn al-Mundhir I (391–418)

- Jabalah III ibn al-Nu‘man (418–434)

- al-Nu‘man IV ibn al-Aiham (434–455) with...

- al-Harith III ibn al-Aiham (434–456) and...

- al-Nu‘man V ibn al-Harith (434–453)

- al-Mundhir II ibn al-Nu‘man (453–472) with...

- ‘Amr III ibn al-Nu‘man (453–486) and...

- Hijr ibn al-Nu‘man (453–465)

- al-Harith IV ibn Hijr (486–512)

- Jabalah IV ibn al-Harith (512–529)

- al-Amr IV ibn Machi (Mah’shee) (529)

- al-Harith V ibn Jabalah (529–569)

- al-Mundhir III ibn al-Harith (569–581) with...

- Abu Kirab al-Nu‘man ibn al-Harith (570–582)

- al-Nu'man VI ibn al-Mundhir (581–583)

- al-Harith VI ibn al-Harith (583)

- al-Nu‘man VII ibn al-Harith Abu Kirab (583–?)

- al-Aiham ibn Jabalah (?–614)

- al-Mundhir IV ibn Jabalah (614–?)

- Sharahil ibn Jabalah (?–618)

- Amr IV ibn Jabalah (628)

- Jabalah V ibn al-Harith (628–632)

- Jabalah VI ibn al-Aiham (632–638)

Legacy

The Ghassanids reached their peak under al-Harith V and al-Mundhir III. Both were militarily successful allies of the Byzantines, especially against their enemies the Lakhmids, and secured Byzantium's southern flank and its political and commercial interests in Arabia proper. On the other hand, the Ghassanids remained fervently dedicated to Miaphysitism, which brought about their break with Byzantium and Mundhir's own downfall and exile, which was followed after 586 by the dissolution of the Ghassanid federation.[24] The Ghassanids' patronage of the Miaphysite Syrian Church was crucial for its survival and revival, and even its spread, through missionary activities, south into Arabia. According to the historian Warwick Ball, the Ghassanids' promotion of a simpler and more rigidly monotheistic form of Christianity in a specifically Arab context can be said to have anticipated Islam.[25] Ghassanid rule also brought a period of considerable prosperity for the Arabs on the eastern fringes of Syria, as evidenced by a spread of urbanization and the sponsorship of several churches, monasteries and other buildings. The surviving descriptions of the Ghassanid courts impart an image of luxury and an active cultural life, with patronage of the arts, music and especially Arab-language poetry. In the words of Ball, "the Ghassanid courts were the most important centres for Arabic poetry before the rise of the Caliphal courts under Islam", and their court culture, including their penchant for desert palaces like Qasr ibn Wardan, provided the model for the Umayyad caliphs and their court.[26]

After the fall of the first kingdom in the 7th century, several dynasties, both Christian and Muslim, ruled claiming to be a continuation of the House of Ghassan.[27] Besides the Phocid or Nikephorian Dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, other rulers claimed to be the heirs of the Royal Ghassanids. The Rasulid Sultans ruled from the 13th until the 15th century in Yemen.[28] And the Burji Mamluk Sultans in Egypt from the 14th until the 16th century.[29] The last rulers to bear the titles of Royal Ghassanid successors were the Christian Sheikhs Al-Chemor in Mount Lebanon ruling the small sovereign sheikhdoms of Akoura (from 1211 until 1641 CE) and Zgharta-Zwaiya (from 1643 until 1747 CE).[30]

Notes and references

- Fisher 2018.

- Saudi Aramco World: The Kind of Ghassan. Barry Hoberman. http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/198302/the.king.of.ghassan.htm Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 31 January 2014.

- Bowersock, G. W.; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg (1998). Late Antiquity: A guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press.

Late Antiquity - Bowersock/Brown/Grabar.

- "Deir Gassaneh".

- bury, john. History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I. to the Death of Justinian, Part 2. courier dover publications.

- Hoberman, Barry. The King of Ghassan. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume II (C-G): [Fasc. 23-40, 40a]. Brill. 28 May 1998. p. 1020. ISBN 978-90-04-07026-4.

- Cuvigny & Robin 1996, pp. 704–706.

- Bukharin 2009, p. 68.

- Irfan Shahid, 1989, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century.

- Fisher, Greg (2015). Arabs and Empires Before Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-19-965452-9.

- Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, vol. 1, Irfan Shahîd, 1995, p. 103

- Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 2 part 2, Irfan Shahîd, pg. 164

- Through the Ages in Palestinian Archaeology: An Introductory Handbook, p. 160, at Google Books

- "History". Sovereign Imperial & Royal House of Ghassan. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014.

- Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, vol. 2, part 1, Irfan Shahîd 1995, p. 51

- Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, vol. 2, part 1, Irfan Shahîd 1995, p. 51-104

- Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, vol. 2, part 1, Irfan Shahîd, 1995, p. 51

- The Origins of the Islamic State, being a translation from the Arabic of the Kitab Futuh al-Buldha of Ahmad ibn-Jabir al-Baladhuri, trans. by P. K. Hitti and F. C. Murgotten, Studies in History, Economics and Public Law, LXVIII (1916-1924), I, 208-209

- Ghassan Resurrected, Yasmine Zahran 2006, p. 13

- Ghassan post Ghassan, Irfan Shahid, Festschrift "The Islamic World - From classical to modern times", for Bernard Lewis, Darwin Press 1989, p. 325

- Ghassan post Ghassan, Irfan Shahid, Festschrift "The Islamic World - From classical to modern times", for Bernard Lewis, Darwin Press 1989, p. 334

- Tarik, Tabari (Cairo, 1966), VIII, p. 307

- Ball 2000, pp. 102–103; Shahîd 1991, pp. 1020–1021.

- Ball 2000, p. 105; Shahîd 1991, p. 1021.

- Ball 2000, pp. 103–105; Shahîd 1991, p. 1021.

- Late Antiquity - Bowesock/Brown/Grabar, Harvard University Press, 1999, p. 469

- Ghassan post Ghassan, Irfan Shahid, Festschrift "The Islamic World - From classical to modern times", for Bernard Lewis, Darwin Press 1989, p. 332

- Ghassan post Ghassan, Irfan Shahid, Festschrift "The Islamic World - From classical to modern times", for Bernard Lewis, Darwin Press 1989, p. 328

- http://nna-leb.gov.lb/ar/show-report/371/

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Almaqhafi, Awwad: Qabayl Wa Biton Al-Arab

- Almsaodi, Abdulaziz; Tarikh Qabayl Al-Arab

- Bosra of the Ghassanids in the Catholic Encyclopedia Newadvent.org

Secondary literature

- Ball, Warwick (2000). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-02322-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bukharin, Mikhail D. (2009). "Towards the Earliest History of Kinda" (PDF). Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 20 (1): 64–80.

- Cuvigny, Hélène; Robin, Christian (1996). "Des Kinaidokolpites dans un ostracon grec du désert oriental (Égypte)". Topoi. Orient-Occident. 6 (2): 697–720.

- Fisher, Greg (2018). "Jafnids". In Oliver Nicholson (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Vol. 2: J–Z. Oxford University Press. p. 804.

- Fowden, Elizabeth Key (1999). The Barbarian Plain: Saint Sergius Between Rome and Iran. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21685-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14687-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Millar, Fergus: "Rome's 'Arab' Allies in Late Antiquity". In: Henning Börm - Josef Wiesehöfer (eds.), Commutatio et Contentio. Studies in the Late Roman, Sasanian, and Early Islamic Near East. Wellem Verlag, Düsseldorf 2010, pp. 159–186.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1991). "Ghassānids". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1991). "Ghassān". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden and New York: Brill. pp. 462–463. ISBN 90-04-07026-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 1. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-214-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)