Pope Clement I

Pope Clement I (Latin: Clemens Romanus; Greek: Κλήμης Ῥώμης; died 99), also known as Saint Clement of Rome, is listed by Irenaeus and Tertullian as Bishop of Rome, holding office from 88 to his death in 99.[2] He is considered to be the first Apostolic Father of the Church, one of the three chief ones together with Polycarp and Ignatius of Antioch.[3]

Pope Saint Clement I | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

c. 1000 portrayal at Saint Sophia's Cathedral, Kiev | |

| Diocese | Rome |

| See | Holy See |

| Papacy began | 88 AD |

| Papacy ended | 99 AD |

| Predecessor | Anacletus |

| Successor | Evaristus |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | by Saint Peter |

| Personal details | |

| Born | ca. 35 AD Rome, Roman Empire |

| Died | 99 AD (aged 63-64) Chersonesus, Taurica, Bosporan Kingdom (modern-day Crimea, Ukraine/Russia) |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day |

|

| Venerated in |

|

| Attributes |

|

| Patronage | |

| Shrines | Basilica di San Clemente, Rome St Clement's Church, Moscow |

| Other popes named Clement | |

Few details are known about Clement's life. Clement was said to have been consecrated by Peter,[3] and he is known to have been a leading member of the church in Rome in the late 1st century. Early church lists place him as the second or third[2][4] bishop of Rome after Peter. The Liber Pontificalis states that Clement died in Greece in the third year of Emperor Trajan's reign, or 101 AD.

Clement's only genuine extant writing is his letter to the church at Corinth (1 Clement) in response to a dispute in which certain presbyters of the Corinthian church had been deposed.[2] He asserted the authority of the presbyters as rulers of the church on the ground that the Apostles had appointed such.[2] His letter, which is one of the oldest extant Christian documents outside the New Testament, was read in church, along with other epistles, some of which later became part of the Christian canon. These works were the first to affirm the apostolic authority of the clergy.[2] A second epistle, 2 Clement, was attributed to Clement, although recent scholarship suggests it to be a homily by another author.[2] In the legendary Clementine Literature, Clement is the intermediary through whom the apostles teach the church.[2]

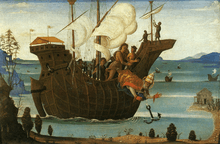

According to tradition, Clement was imprisoned under the Emperor Trajan; during this time he is recorded to have led a ministry among fellow prisoners. Thereafter he was executed by being tied to an anchor and thrown into the sea.[2] Clement is recognized as a saint in many Christian churches and is considered a patron saint of mariners. He is commemorated on 23 November in the Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, and the Lutheran Church.[5] In Eastern Orthodox Christianity his feast is kept on 24 or 25 November.

Life

The Liber Pontificalis[6] presents a list that makes Pope Linus the second in the line of bishops of Rome, with Peter as first; but at the same time it states that Peter ordained two bishops, Linus and Pope Cletus, for the priestly service of the community, devoting himself instead to prayer and preaching, and that it was to Clement that he entrusted the Church as a whole, appointing him as his successor. Tertullian considered Clement to be the immediate successor of Peter.[7] In one of his works, Jerome listed Clement as "the fourth bishop of Rome after Peter, if indeed the second was Linus and the third Anacletus, although most of the Latins think that Clement was second after the apostle."[8] Clement is put after Linus and Cletus/Anacletus in the earliest (c. 180) account, that of Irenaeus,[9] who is followed by Eusebius of Caesarea.[10]

Early succession lists name Clement as the first,[11][12] second, or third[2][13] successor of Peter. However, the meaning of his inclusion in these lists has been very controversial.[14] Some believe there were presbyter-bishops as early as the 1st century,[14] but that there is no evidence for a monarchical episcopacy in Rome at such an early date.[2] There is also, however, no evidence of a change occurring in ecclesiastical organization in the latter half of the 2nd century, which would indicate that a new or newly-monarchical episcopacy was establishing itself.[14] Also Dionysius of Corinth and Irenaeus of Lyon both viewed Clement as a monarchial bishop who intervened in the dispute in the church of Corinth.

A tradition that began in the 3rd and 4th century,[2] has identified him as the Clement that Paul mentioned in Philippians 4:3, a fellow laborer in Christ.[15] While in the mid-19th century it was customary to identify him as a freedman of Titus Flavius Clemens, who was consul with his cousin, the Emperor Domitian, this identification, which no ancient sources suggest, afterwards lost support.[3] The 2nd-century Shepherd of Hermas mentions a Clement whose office it was to communicate with other churches; most likely, this is a reference to Clement I.[16]

A large congregation existed in Rome c. 58, when Paul wrote his Epistle to the Romans.[2] Paul arrived in Rome c. 60 (Acts).[2] His Captivity Epistles, as well as Mark, Luke, Acts, and 1 Peter were written here, according to many scholars. Paul and Peter were said to have been martyred there. Nero persecuted Roman Christians after Rome burned in 64, and the congregation may have suffered further persecution under Domitian (81–96). Clement was the first of early Rome's most notable bishops.[17]

The Liber Pontificalis, which documents the reigns of popes, states that Clement had known Peter.

Clement is known for his epistle to the church in Corinth (c. 96), in which he asserts the apostolic authority of the bishops/presbyters as rulers of the church.[2] The epistle mentions episkopoi (overseers, bishops) or presbyteroi (elders, presbyters) as the upper class of minister, served by the deacons, but, since it does not mention himself, it gives no indication of the title or titles used for Clement in Rome.

Death and legends of final days

According to apocryphal acta dating to the 4th century at earliest, Clement was banished from Rome to the Chersonesus during the reign of the Emperor Trajan[2][3] and was set to work in a stone quarry. Finding on his arrival that the prisoners were suffering from lack of water, he knelt down in prayer. Looking up, he saw a lamb on a hill, went to where the lamb had stood and struck the ground with his pickaxe, releasing a gushing stream of clear water. This miracle resulted in the conversion of large numbers of the local pagans and his fellow prisoners to Christianity. As punishment, Clement was martyred by being tied to an anchor[18] and thrown from a boat into the Black Sea. The legend recounts that every year a miraculous ebbing of the sea revealed a divinely built shrine containing his bones. However, the oldest sources on Clement's life, Eusebius and Jerome, note nothing of his martyrdom.[19]

The Inkerman Cave Monastery marks the supposed place of Clement's burial in the Crimea. A year or two before his own death in 869, Cyril brought to Rome what he believed to be the relics of Saint Clement, bones he found in the Crimea buried with an anchor on dry land. They are now enshrined in the Basilica di San Clemente.[3] Other relics of Saint Clement, including his head, are claimed by the Kiev Monastery of the Caves in Ukraine.

Writings

The Liber Pontificalis states that Clement wrote two letters (though the second letter, 2 Clement, is no longer ascribed to him by many modern scholars).

Epistle of Clement

Clement's only extant, uncontested text is a letter to the Christian congregation in Corinth, often called the First Epistle of Clement or 1 Clement. The history of 1 Clement clearly and continuously shows Clement as the author of this letter. It is considered the earliest authentic Christian document outside the New Testament.

Clement writes to the troubled congregation in Corinth, where certain "presbyters" or "bishops" have been deposed (the class of clergy above that of deacons is designated indifferently by the two terms).[2] Clement calls for repentance and reinstatement of those who have been deposed, in line with maintenance of order and obedience to church authority, since the apostles established the ministry of "bishops and deacons." [2] He mentions "offering the gifts" as one of the functions of the higher class of clergy.[2] The epistle offers valuable insight into Church ministry at that time and into the history of the Roman Church.[2] It was highly regarded, and was read in church at Corinth along with the Scriptures c. 170.[2]

We should be obedient unto God, rather than follow those who in arrogance and unruliness have set themselves up as leaders in abominable jealousy.... For Christ is with them that are lowly of mind, not with them that exalt themselves over the flock. 1Clem 14:1; 16:1

Do we then think it to be a great and marvelous thing, if the Creator of the universe shall bring about the resurrection of them that have served Him with holiness in the assurance of a good faith, seeing that He showeth to us even by a bird the magnificence of His promise? 1Clem 26:1

In the epistle, Clement uses the terms "bishop" and "presbyter" interchangeably for the higher order of ministers above deacons.[2] In some congregations, particularly in Egypt, the distinction between bishops and presbyters seems to have become established only later.[20] But by the middle of the second century all the leading Christian centres had bishops.[20] Scholars such as Bart Ehrman treat as significant the fact that, of the seven letters written by Ignatius of Antioch to seven Christian churches shortly after the time of Clement, the only one that does not present the church as headed by a single bishop is that addressed to the church in Rome, although this letter did not refer to a collective priesthood either.[21]

The epistle has been cited as the first work to establish Roman primacy, but most scholars see the epistle as more fraternal than authoritative,[22] and Orthodox scholar John Meyendorff sees it as connected with the Roman church's awareness of its "priority" (rather than "primacy") among local churches.[23]

Writings formerly attributed to Clement

Second Epistle of Clement

The Second Epistle of Clement is a homily, or sermon, likely written in Corinth or Rome, but not by Clement.[2] Early Christian congregations often shared homilies to be read. The homily describes Christian character and repentance.[2] It is possible that the Church from which Clement sent his epistle had included a festal homily to share in one economical post, thus the homily became known as the Second Epistle of Clement.

While 2 Clement has been traditionally ascribed to Clement, most scholars believe that 2 Clement was written in the 2nd century based on the doctrinal themes of the text and a near match between words in 2 Clement and in the Greek Gospel of the Egyptians.[3][24]

Epistles on Virginity

Two "Epistles on Virginity" were traditionally attributed to Clement, but now there exists almost universal consensus that Clement was not the author of those two epistles.[25]

False Decretals

A 9th-century collection of church legislation known as the False Decretals, which was once attributed to Isidore of Seville, is largely composed of forgeries. All of what it presents as letters of pre-Nicene popes, beginning with Clement, are forgeries, as are some of the documents that it attributes to councils;[26] and more than forty falsifications are found in the decretals that it gives as those of post-Nicene popes from Pope Sylvester I (314–335) to Pope Gregory II (715–731). The False Decretals were part of a series of falsifications of past legislation by a party in the Carolingian Empire whose principal aim was to free the church and the bishops from interference by the state and the metropolitan archbishops respectively.[27][28][29]

Clement is included among other early Christian popes as authors of the Pseudo-Isidoran (or False) Decretals, a 9th-century forgery. These decrees and letters portray even the early popes as claiming absolute and universal authority.[30] Clement is the earliest pope to whom a text is attributed.

Clementine literature

St. Clement is also the hero of an early Christian romance or novel that has survived in at least two different versions, known as the Clementine literature, where he is identified with Emperor Domitian's cousin Titus Flavius Clemens. Clementine literature portrays Clement as the Apostles' means of disseminating their teachings to the Church.[2]

Recognition as a saint

St. Clement's name is in the Roman Canon of the Mass. He is commemorated on 23 November as a Pope and martyr in the Catholic Church as well as within the Anglican Communion and the Lutheran Church. The Syriac Orthodox Church, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, the Macedonian Orthodox Church and the Greek Orthodox Church, as well as the Syriac Catholic Church, the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church and all Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic Churches commemorate Saint Clement of Rome (called in Syriac "Mor Clemis") on 24 November; the Russian Orthodox Church commemorates St Clement on 25 November.

The St Clement's Church in Moscow is renowned for its glittering Baroque interior and iconostasis, as well as a set of gilded 18th-century railings. The parish was disbanded in 1934 and the original free-standing gate was demolished. The Lenin State Library stored its books in the building throughout the Soviet period. It was not until 2008 that the building reverted to the Russian Orthodox Church.

Saint Clement of Rome is commemorated in the Synaxarium of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria on the 29th of the month of Hatour [25 November (Julian) – equivalent to 8 December (Gregorian) due to the current 13-day Julian–Gregorian Calendar offset]. According to the Coptic Church Synaxarium, he suffered martyrdom in AD 100 during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98–117). He was martyred by tying his neck to an anchor and casting him into the sea. The record of the 29th of the Coptic month of Hatour states that this saint was born in Rome to an honorable father whose name was Fostinus and also states that he was a member of the Roman senate and that his father educated him and taught him Greek literature.

Relics

In the city of Santa Cruz de Tenerife in Spain, it is the shinbone of San Clemente, gift of Patriarch Sidotti (Patriarch of Antioch) to the Church of the Immaculate Conception. Historically this was a highly revered relic in the city.[31]

Symbolism

In works of art, Saint Clement can be recognized by having an anchor at his side or tied to his neck. He is most often depicted wearing papal vestments, including the pallium, and sometimes with a papal tiara but more often with a mitre. He is also sometimes shown with symbols of his office as Pope or Bishop of Rome such as the papal cross and the Keys of Heaven. In reference to his martyrdom, he often holds the palm of martyrdom.

Saint Clement can be seen depicted near a fountain or spring, relating to the incident from his hagiography, or lying in a temple in the sea. The Anchored Cross or Mariner's Cross is also referred to as St. Clement's Cross, in reference to the way he was martyred.[18]

See also

- List of popes

- List of Catholic saints

- Pope Saint Clement I, patron saint archive

- St Clement's Day

References

- "Patron Saints and their feast days". Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- "Clement of Rome, St." Cross, F. L. (ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Chapman, John. "Pope St. Clement I." in The Catholic Encyclopedia 1908

- The Catholic Encyclopedia says that no critic now doubts that the names Cletus and Anacletus in lists that would make Clement the fourth successor of Saint Peter refer to the one person, not two.

- See Calendar of Saints (Lutheran)

- Liber Pontificalis 2

- "CHURCH FATHERS: The Prescription Against Heretics (Tertullian)".

- "CHURCH FATHERS: De Viris Illustribus (Jerome)".

- Against Heresies3:3.3 "In the third place from the apostles, Clement was allotted the bishopric."

- Church History 3.4.10 "Clement ... was appointed third bishop of the church at Rome"

- "History of the Christian Church, Volume II: Ante-Nicene Christianity. A.D. 100-325".

- Like Schaff, the Holy See's Annuario Pontificio (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2008 ISBN 978-88-209-8021-4), p. 7*, gives Clement as "supreme pontiff of Rome" in either 92–99 or 68–76, making him either the first or the third successor of Saint Peter, but not the second.

- The Catholic Encyclopedia article says that only on the false assumption that "Cletus" and "Anacletus" were two distinct persons, instead of variations of the name of single individual, did some think that Clement was the fourth successor of Saint Peter.

- Van Hove, Alphonse. "Bishop." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 6 Dec. 2008

- "Writers of the 3rd and 4th cents., like Origen, Eusebius, and Jerome, equate him (St. Clement I), perhaps, correctly, with the Clement whom St. Paul mentions (Phil. 4:3) as a fellow worker." — Kelly (1985). The Oxford Dictionary of Popes. Oxford University Press. p. 7.

- "Vision II," 4. 3

- "Rome (early Christian)." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- Stracke, Richard (2015-10-20). "Saint Clement: The Iconography". Christian Iconography.

- "But the oldest witnesses, down to Eusebius and Jerome, know nothing of his martyrdom." History of the Christian Church, Volume II: Ante-Nicene Christianity, AD 100–325 – "Clement of Rome"

- "Bishop." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- Bart D. Ehrman, Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene: The Followers of Jesus in History and Legend (Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 978-0-19974113-7), p. 83

- "Most scholars would now regard 1 Clement as an impressive example of fraternal correction rather than an authoritative intervention." Patrick Granfield and Peter C. Phan, The Gift of the Church: A Textbook On Ecclesiology In Honor Of Patrick Granfield, O.S.B, (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2000), p. 32.

- John Meyendorff, The Primacy of Peter: Essays in Ecclesiology and the Early Church (St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1992), p. 135–136

- McBrien (2000). Lives of the Popes. HarperCollins. p. 35.

- "Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol VIII: Two Epistles Concerning Virginity.: Introductory Notice".

- The Encyclopædia Britannica places the Donation of Constantine in this section; the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church places it in the section of the pre-Nicene Popes.

- Encyclopædia Britannica: False Decretals

- OSV's Encyclopedia of Catholic History: False Decretals

- Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3)] False Decretals

- "These early documents were designed to show that by the oldest traditions and practice of the Church no bishop might be deposed, no Church councils might be convened, and no major issue might be decided, without the consent of the pope. Even the early pontiffs, by these evidences, had claimed absolute and universal authority as vicars of Christ on Earth." Durant, Will. The Age of Faith. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972. p. 525

- Fiestas y creencias en Canarias en la Edad Moderna

Further reading

- Clarke, W. K. Lowther, ed. (1937). The First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians. London: Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge.

- Grant, Robert M., ed. (1964). The Apostolic Fathers. New York: Nelson.

- Loomis, Louise Ropes (1916). The Book of Popes (Liber Pontificalis). Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 1-889758-86-8.

- Lightfoot, J.B. (1890). The Apostolic Fathers. London: Macmillan.

- Meeks, Wayne A. (1993). The origins of Christian morality : the first two centuries. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05640-2.

- Richardson, Cyril Charles (1943). Early Christian Fathers. The Library of Christian Classics. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

- Staniforth, Maxwell (1968). Early Christian writings. Baltimore: Penguin.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Clement I |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: First Epistle of Clement |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clemens I. |

- "Saint Clement I." Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Works by or about Pope Clement I at Internet Archive

- Works by Pope Clement I at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Two Epistles Concerning Virginity .

- Opera Omnia

- Hieromartyr Clement the Pope of Rome Eastern Orthodox icon and synaxarion

- Patron Saints Index: Pope Saint Clement I

- Saint Clement at the Christian Iconography web site

- "Here Followeth the Life of St. Clement" in the Caxton translation of the Golden Legend

- "St. Clement of Rome, Pope and Martyr (1st Century)"

- Colonnade Statue in St Peter's Square

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Anacletus |

Bishop of Rome Pope 88–99 |

Succeeded by Evaristus |