Anti-Croat sentiment

Anti-Croat sentiment is discrimination or prejudice towards Croats as an ethnic group and negative feelings towards Croatia as a country.

Nationalism in the 19th century

With the nation-building process in mid-19th century, first Croatian-Serbian tension appeared. Serbian minister Ilija Garašanin's Načertanije (1844)[1]:3 claimed lands that were inhabited by Bulgarians, Macedonians, Albanians, Montenegrins, Bosnians, Hungarians and Croats were part of Serbia.[1]:3 Garašanin's plan also includes methods of spreading Serbian influence in the claimed lands.[1]:3–4 He proposed ways to influence Croats, who Garašanin regarded as "Serbs of Catholic faith".[1]:3 This plan considered surrounding peoples to be devoid of national consciousness.[1]:3–4[2]:91 Vuk Karadžić in the 1850s then denied the existence of Croatians and Croatian language anywhere in the Balkans, save for some of the northern parts of Slavonia. Those living in the Balkans, he labeled as Serbs. Croatia was at the time a kingdom in Habsburg Monarchy, with Dalmatia and Istria being separate Habsburg Crown lands. Ante Starčević, head of the Croatian Party of Rights, advocated for Croatia as a nation.[3] After Austro-Hungary occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878 and Serbia gained its independence from Ottoman Empire, Croatian and Serbian relations deteriorated as both sides had pretensions on Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1902 there was a reprinted article written by Serb Nikola Stojanović that was published in the publication of the Serbian Independent Party from Zagreb titled Do istrage vaše ili naše (Till the Destruction, ours or yours) in which denying of the existence of Croat nation as well as forecasting the result of the "inevitable" Serbian-Croatian conflict occurred.

That combat has to be led till the destruction, either ours or yours. One side must succumb. That side will be Croatians, due to their minority, geographical position, mingling with Serbs and because the process of evolution means Serbhood is equal to progress.[4]

— Nikola Stojanović, Srbobran, 10.08.1902.

During the 19th century, some Italian radical nationalists tried to promote the idea that a Croatian nation has no sound reason to exist: therefore the Slavic population on the east coast of the Adriatic Sea (Croats and Slovenes) should be Italianized, and the territory included in Italy.[5]

World War II

Fascist Italy

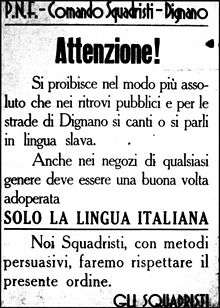

Fascist-led Italianization, or the forced assimilation of Italian culture on the ethnic Croat communities inhabiting the former Austro-Hungarian territories of the Julian March and areas of Dalmatia, as well as ethnically-mixed cities in Italy proper, such as Trieste, had already been initiated prior to World War II. The Anti-Slavic sentiment, perpetuated by Italian Fascism, led to the persecution of Croats, alongside ethnic Slovenes on ethnic and cultural grounds.

In September 1920, Mussolini said:

When dealing with such a race as Slavic - inferior and barbaric - we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy. We should not be afraid of new victims. The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps. I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians.

This period of Fascist Italianization included the banning of Croatian in administration and courts between 1923 and 1925,[7] the Italianization of Croat given and surnames in 1926[8][9] and the dissolution of Croatian societies, financial co-operatives and banks.[10]

This period was therefore characterised as "centralising, oppressive and dedicated to the forcible Italianisation of the minorities" [11] consequently leading to a strong emigration and assimilations of Slovenes and Croats from the Julian March.[12]

Following the Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, Italy occupied almost all of Dalmatia, as well as Gorski Kotar and the Italian government made stringent efforts to further Italianize the region. Italian occupying forces were accused of committing war crimes in order to transform occupied territories into ethnic Italian territories.[13] An example of this was the 1942 massacre in Podhum and Testa, when Italian forces murdered at least 108 Croat civilians and deported the remaining population to concentration camps.[14]

The Italian government operated concentration camps[15] for Slavic citizens, such as Rab concentration camp and one on the island of Molat.

Chetniks

Regarding the realization of his Greater Serbian program Homogenous Serbia, Stevan Moljević wrote in his letter to Dragiša Vasić in February 1942:[16]

(...) 2) Regarding our internal affairs, the demarcation with the Croats, we hold that we should as soon as an opportunity occurs, gather all the strength and create a completed act: occupy territories marked on the map, clean it before anyone pulls itself together. We would assume that the occupation would only be carried out if the main hubs were strong in Osijek, Vinkovci, Slavonski Brod, Sunja, Karlovac, Knin, Šibenik, Mostar and Metković, and then from within start with an [ethnic] cleansing of all non-Serb elements. The guilty should have an open way - Croats to Croatia, Muslims to Turkey (or Albania). As for the Muslims, our government in London should immediately address the issue with Turkey. English will also help us. (Question is!). The organization for the interior cleansing should be prepared immediately, and it could be because there are many refugees in Serbia from all "Serb lands" (...).

The tactics employed against the Croats were at least to an extent, a reaction to the terror carried out by the Ustaše, but Croats and Bosniaks living in areas intended to be part of Greater Serbia were to be cleansed of non-Serbs regardless, in accordance with Mihailović's directive of 20 December 1941.[17] However the largest Chetnik massacres took place in eastern Bosnia where they preceded any significant Ustashe operations.[18] Chetnik ethnic cleansing targeted Croat civilians throughout areas of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, in which Croats were massacred and expelled, such as the Krnjeuša massacre and the Gata massacre. According to the Croatian historian, Vladimir Žerjavić, Chetnik forces killed between 18,000-32,000 Croats during World War II, mostly civilians.[19] Some historians regard Chetnik actions during this period as constituting genocide.[20][21][22]

Written evidence by Chetnik commanders indicates that terrorism against the non-Serb population was mainly intended to establish an ethnically-pure Greater Serbia in the historical territory of other ethnic groups (most notably Croatian and Muslim, but also Bulgarian, Romanian, Hungarian, Macedonian and Montenegrin). In the "Elaborate" of the Chetnik's Dinaric Battalion from March 1942, it's stated that the Chetniks' main goal was to create a "Serbian national state in the areas in which the Serbs live, and even those to which Serbs aspire (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Lika and part of Dalmatia) where "only Orthodox population would live".[16] It is also stated that Bosniaks should be convinced that Serbs are their allies, so they wouldn't join the Partisans, and then kill them."[23]

Regarding the campaign, Chetnik commander Milan Šantić said in Trebinje in July 1942, "The Serb lands must be cleansed from Catholics and Muslims. They will be inhabited only by the Serbs. Cleansing will be carried out thoroughly, and we will suppress and destroy them all without exception and without pity, which will be the starting point for our liberation.[24] Mihailović went further than Moljević and requested over 90 percent of the NDH's territory, where more than 2,500,000 Catholics and over 800,000 Muslims lived (70 percent of the total population, with Orthodox Serbs the remaining 30 percent). [24]

According to Bajo Stanišić, the final goal of the Chetniks was "founding of a new Serbian state, not a geographical term but a purely Serbian, with four basic attributes: the Serbian state [Greater Serbia], the Serb King [of] the Karađorđević dynasty, Serbian nationality, and Serbian faith. The Balkan federation is also the next stage, but the main axis and leadership of this federation must be our Serbian state, that is, the Greater Serbia.[25]

Yugoslav Wars

After Serbian President Slobodan Milošević's assumption of power in 1989 various Chetnik groups made a "comeback"[26] and his regime "made a decisive contribution to launching the Chetnik insurrection in 1990–1992 and to funding it thereafter," according to the political scientist Sabrina P. Ramet.[27] Chetnik ideology was influenced by the memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.[27] Serbs in north Dalmatia, Knin, Obrovac, and Benkovac held the first anti-Croatian government demonstrations.[28] On 28 June 1989, the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo, exiled Croatian Serb Chetnik commander Momčilo Đujić bestowed the Serbian politician Vojislav Šešelj with the title of vojvoda, encouraging him to "expel all Croats, Albanians, and other foreign elements from holy Serbian soil", stating he would return to the Balkans only when Serbia was cleansed of "the last Jew, Albanian, and Croat".[29]

Šešelj is a major proponent of a Greater Serbia with no ethnic minorities, but "ethnic unity and harmony among Orthodox Serbs, Catholic Serbs, Muslim Serbs and atheist Serbs".[30] In late 1991, during the Battle of Vukovar, Šešelj went to Borovo Selo to meet with a Serbian Orthodox Church bishop and publicly described Croats as a genocidal and perverted people.[31] In May and July 1992, Šešelj visited the Vojvodina village of Hrtkovci and publicly started the campaign of persecution of local ethnic Croats.[32][33]

16,000 Croats were killed during the Yugoslav Wars, 43.4 percent of whom were civilians.[34] largely through massacres and bombings that occurred during the war.[35] The total number of expelled Croats and other non-Serbs during the Croatian War of Independence ranges from 170,000 (ICTY),[36] 250,000 (Human Rights Watch) [37] or 500,000 (UNHCR).[38] Croatian Serbs forces together with Yugoslav People's Army and Serbian nationalist paramilitaries committed numerous war crimes against Croat civilians.[39]

According to the Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps, a total of 8,000 Croatian civilians and Prisoners of war (a large number after the fall of Vukovar) went through Serb prison camps such as Sremska Mitrovica camp, Stajićevo camp, Niš camp and many others where many were heavily abused and tortured. A total of 300 people never returned from them.[40] A total of 4,570 camp inmates started legal action against former Serbia and Montenegro (now Serbia) for torture and abuse in the camps.[41] Croatia regained control over most of the territories occupied by the Croatian Serb rebels in 1995.

.svg.png) The borders of Great Serbia as propagated by Radical politician Vojislav Šešelj in 1992.[42]

The borders of Great Serbia as propagated by Radical politician Vojislav Šešelj in 1992.[42] Croatian house defaced with graffiti: Serbian cross, "Red Star champion", "Usraše se Ustaše" and "God protects Serbs"

Croatian house defaced with graffiti: Serbian cross, "Red Star champion", "Usraše se Ustaše" and "God protects Serbs"

21st century

Croats were recognised in Serbia as a minority group just after 2002.[43] According to some estimates, the number of Croats who left Serbia under political pressure from the Milošević government may have been between 20,000 and 40,000.[44] According to Tomislav Žigmanov, Croats live in fear as they have become the most hated minority group in Serbia.[45] The Government of Croatia contends that anti-Croat sentiment is still prevalent in Serbia.[46]

Pejorative terms for Croats

- Ustaše: Derogatory slur used primarily by Serbian nationalists in reference to the Independent State of Croatia and the Ustaše movement during World War II.

- Wog (Australia): In Australian English, the slur "wog" is used to refer to immigrants of Southern European, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and sometimes Eastern European ethnicity or appearance, and has thus also been applied to ethnic Croat immigrants.

References

- Cohen, Philip J.; Riesman, David (1996). Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-760-1.

- Anzulovic, Branimir (2001). Heavenly Serbia: From Myth to Genocide. New York University Press. ISBN 1-86403-100-X.

- In the Name of Independence: The Unmaking of Tito's Yugoslavia, Branko Belan, 2010, p. 82,83

- Bilandžić, Dušan (1999). Hrvatska moderna povijest. Golden marketing. p. 31. ISBN 953-6168-50-2.

- "Buying and Selling the Istrian Goat: Istrian Regionalism, Croatian Nationalism, and EU Enlargement", (book), John E. Ashbrook, 2008, Pg. 37

- Verginella, Marta (2011). "Antislavismo, razzismo di frontiera?". Aut aut (in Italian). ISBN 9788865761069.

- PUŞCARIU, Sextil. Studii istroromâne. Vol. II, Bucureşti: 1926

- Regio decreto legge 10 Gennaio 1926, n. 17: Restituzione in forma italiana dei cognomi delle famiglie della provincia di Trento

- Mezulić, Hrvoje; R. Jelić (2005) Fascism, baptiser and scorcher (O Talijanskoj upravi u Istri i Dalmaciji 1918-1943.: nasilno potalijančivanje prezimena, imena i mjesta), Dom i svijet, Zagreb, ISBN 953-238-012-4

- "A Historical Outline Of Istria". Archived from the original on January 11, 2008.

- Sluga, Glenda; Sluga, Professor of International History Glenda (January 11, 2001). "The Problem of Trieste and the Italo-Yugoslav Border: Difference, Identity, and Sovereignty in Twentieth-Century Europe". SUNY Press – via Google Books.

- "Le pulizie etniche in Istria e nei Balcani", Inoslav Bešker, retriewed 29. Feb. 2020

- Z. Dizdar: "Italian Policies Toward Croatians In Occupied Territories During The Second World War", Review of Croatian History Issue no.1 /2005

- "Rivista Anarchica Online". www.arivista.org.

- "ELENCO DEI CAMPI DI CONCENTRAMENTO ITALIANI".

- Nikola Milovanović - DRAŽA MIHAILOVIĆ, chapter "SMERNICE POLITIČKOG PROGRAMA I CILJEVI RAVNOGORSKOG POKRETA", edition "Rad", Belgrade, 1984.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia. Stanford University Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Hoare 2006, p. 143.

- Vladimir Geiger (2012). "Human Losses of the Croats in World War II and the Immediate Post-War Period Caused by the Chetniks (Yugoslav Army in the Fatherand) and the Partisans (People's Liberation Army and the Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia/Yugoslav Army) and the Communist Authorities: Numerical Indicators". Review of Croatian history. Croatian Institute of History. VIII (1): 85–87. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia. Stanford University Press. p. 747. ISBN 978-0-80477-924-1.

- Redžić, Enver (2005). Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Second World War. New York: Taylor and Francis. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-71465-625-0.

- Hoare, Marko (2006). Genocide and Resistance in Hitler's Bosnia: The Partisans and Chetniks, 1941–1943. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 386. ISBN 978-0-19726-380-8.

- "Dinarska četnička divizija (4)". Hrvatski povijesni portal.

- Dizdar & Sobolevski 1999.

- Četnički zločini nad Hrvatima i Muslimanima u Bosni i Hercegovini tijekom Drugog svjetskog rata (1941.-1945.), Zvonimir Despot, Večernji list, 25. March 2020

- Mennecke, Martin (2012). "Genocidal Violence in the Former Yugoslavia". In Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S. Centuries of Genocide: Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87191-4.

- Ramet 2006, p. 420.

- Tanner, Marcus (1997). Croatia : a nation forged in war. Yale University Press. p. 218. ISBN 0300076681.

- Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

- "Vojislav Seselj: I Wanted a 'Greater Serbia'". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Renaud de la Brosse (4 February 2003). "Political Propaganda and the Plan to Create a "State for all Serbs" – Consequences of Using the Media for Ultra-Nationalist Ends – Part 3" (PDF). Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- Marcus Tanner (August 1992). "'Cleansing' row prompts crisis in Vojvodina". The Independent. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Chuck Sudetic (26 July 1992). "Serbs Force An Exodus From Plain". New York Times. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Fink 2010, p. 469.

- index (December 11, 2003). "Utjecaj srbijanske agresije na stanovništvo Hrvatske". Index.hr. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- Marlise Simons (10 October 2001). "Milosevic, Indicted Again, Is Charged With Crimes in Croatia". New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- "Milosevic: Important New Charges on Croatia". Human Rights Watch. 21 October 2001. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- UNHCR (August 5, 2005). "Home again, 10 years after Croatia's Operation Storm". UNHCR. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- "Prosecution submission of an expert report of Reynaud J.M. Theunens pursuant to Rule 94bis" (PDF). The Hague: The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. December 16, 2003. p. 27633-27630, 27573 & 27565-27561. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Natalya Clark, Janine (2014). International Trials and Reconciliation: Assessing the Impact of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. ISBN 9781317974741.

- "Danijel Rehak ponovno izabran za predsjednika Hrvatskog društva logoraša". Vjesnik (in Croatian). 28 March 2004. Archived from the original on 30 April 2004. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- "Granice (srpske)". Biografija: Pojmovnik (in Serbian). Vojislav Šešelj official website. April 1992. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

Srpske granice dopiru do Karlobaga, Ogulina, Karlovca, Virovitice.

- "Srbija - MVEP • Hrvatska manjina u Republici Srbiji". rs.mvep.hr.

- "Informacije za Hrvate izvan domovine". web.archive.org. March 11, 2009.

- "Žigmanov: Hrvati u Srbiji žive u strahu jer su postali najomraženija manjina". N1 HR.

- "Croatian ministers call for putting an end to anti-Croat sentiment in Serbia", the official pages of the Government of the Republic of Croatia, 02. April 2015

External links

- "The U.S. Media and Yugoslavia, 1991-1995" (book), James J. Sadkovich, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998.