Yörüks

The Yörüks, also Yuruks or Yorouks (Turkish: Yörükler; Greek: Γιουρούκοι, Youroúkoi; Bulgarian: юруци; Macedonian: Јуруци, Juruci), are a Turkish ethnic subgroup,[2] some of whom are nomadic, primarily inhabiting the mountains of Anatolia, and partly in the Balkan peninsula. Their name derives from the Turkish verb yürü- (yürümek in infinitive), which means "to walk", with the word yörük or yürük designating "those who walk on the hindlegs, walkers".[3][4] Yörüks lived within the Yörük Sanjak (Turkish: Yörük Sancağı) which was not a territorial unit like other sanjaks but a separate organisational unit of the Ottoman Empire.[5][6]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Anatolia, Balkans | |

| Languages | |

| Rumelian Turkish,[1] Turkish | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam and Alevism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Turkish people and other Turkic peoples |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Turkish people |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Anatolia

Historians and ethnologists often use the additional appellative 'Yörük Turcoman' or 'Turkmens' to describe the Yörüks of Anatolia. In Turkey's general parlance today, the terms "Türkmen" and "Yörük" indicate the gradual degrees of preserved attachment with the former semi-nomadic lifestyle of the populations concerned, with the "Turkmen" now leading a fully sedentary life, while keeping parts of their heritage through folklore and traditions, in arts like carpet-weaving, with the continued habit of keeping a yayla house for the summers, sometimes in relation to the Alevi community etc. and with Yörüks maintaining a stronger association with nomadism. These names ultimately hint to their Oghuz Turkish roots. The remaining "true" Yörüks of today's Anatolia traditionally use horses as a means of transportation, though these are steadily being replaced by trucks.

The Yörüks are divided in a large number of named endogamous patrilineal tribes (aşiret). Among recent tribes mentioned in the literature are Aksigirli, Ali Efendi, Bahsıs, Cakallar, Coşlu, Qekli, Gacar, Güzelbeyli, Horzum, Karaevli, Karahacılı, Karakoyunlu, Karakayalı, Karalar, Karakeçili, Manavlı, Melemenci, San Agalı, Sanhacılı, Sarıkeçili, Tekeli and Yeni Osmanlı. The tribes are splittered in clans or lineages, i.e. kabile, sülale or oba.[7]

Lifestyle

French historian and Turkologist Jean-Paul Roux visited the Anatolian Yörüks in the late 1950s and found that the majority of them were practicing Sunni Muslims.[8] The tribes he visited were led by elected officials called muhtars, or village headmen, rather than hereditary chiefs, although he did note that village elders maintained some social authority based on their age.[9] For the majority of the year, they lived in dark wool tents called kara fadir.[10] During the summer, they went up to the mountains, and in the winter they came down to the coastal plains.[11] They kept a variety of animals, including goats, sheep, camels, and sometimes cattle.[12]

The focus of each tribe was the family unit. Young men would move directly from their family's tent to their own upon marriage. The Yörüks married endogamously; that is, they married strictly within their own tribe. Children were raised by the tribe as a whole, who told Roux "we are all parents."[13] Although the Yörüks had acquired a reputation for being deliberately resistant to formal education, Roux found that a full quarter of Yörük children he encountered were attending school, despite the difficulties of living a nomadic lifestyle in remote locations with limited access.[14]

Balkans

In 1911, the Yörük were a distinct segment of the population of Macedonia and Thrace, where they settled as early as the 14th century.[15] An earlier offshoot of the Yörüks, the Kailar or Kayılar Turks, were among the first settlements in Europe.

Yörüks and Sarakatsani

Their nomadic way of life and the fact that they spread through the Balkans led Arnold van Gennep to try to establish a connection between the Yörüks and the ethnically Greek Sarakatsani (Greek: Σαρακατσάνοι) or Karakachans of Greece.[16] However, the Sarakatsani when for the first time mentioned under this name were Orthodox Christians and speaking Greek. Despite some connections and similarities as to the transhumant, nomadic way of life[17], there are no actual linguistic or religious links. On the contrary, a popular theory based on cultural and linguistic data suggests that Sarakatsani are of Dorian descent. [18][19][20][21][22]

Kayılar Yörüks

The Kailar Turks formerly inhabited parts of Thessaly and Macedonia (especially near the town of Kozani and modern Ptolemaida). Before 1360, large numbers of nomad shepherds, or Yörüks, from the district of Konya, in Asia Minor, had settled in the country. Further immigration from this region took place from time to time up to the middle of the 18th century. After the establishment of the feudal system in 1397 many of the Seljuk noble families came over from Asia Minor; some of the beys or Muslim landowners in southern Macedonia before the Balkan Wars may have been their descendants.[15]

Iran

Clans closely related to the Yörüks are scattered throughout the Anatolian Peninsula and beyond it, particularly around the chain of Taurus Mountains and further east around the shores of the Caspian sea. Of the Turkmens of Iran, the Yomuts come the closest to the definition of the Yörüks. An interesting offshoot of the Yörük mass are the Tahtadji of the mountainous regions of Western Anatolia who, as their name implies, have been occupied with forestry work and wood craftsmanship for centuries. Despite this, they share similar traditions (with markedly matriarchal tones in their society structure) with their other Yörük cousins. The Qashqai people of southern Iran are also worthy of mention due to their shared characteristics.

Northern Cyprus

A considerable number of the original Turkish population of Northern Cyprus are also of Yörük descent.

Gallery

Kailar (Kayılar), Yörük baby in traditional taç

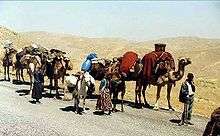

Kailar (Kayılar), Yörük baby in traditional taç_p010_YOUROUK_ENCAMPMENT_IN_THE_TAURUS.jpg) Yörük camp in the Taurus Mountains, c. 1879

Yörük camp in the Taurus Mountains, c. 1879 Yörük encampment, c. 1893

Yörük encampment, c. 1893

.jpg) The first settlements of Kailar Yörüks in Erdemuş

The first settlements of Kailar Yörüks in Erdemuş Kailar Yörüks in center of Kailar as a formal name of Cuma Pazarı

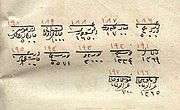

Kailar Yörüks in center of Kailar as a formal name of Cuma Pazarı Sultan Selim II's firman for Kailar Yörüks

Sultan Selim II's firman for Kailar Yörüks Yörük women at the spring

Yörük women at the spring

See also

Notes

- "Balkan Gagauz Turkish". Ethnologue. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Vakalopoulos, Apostolos Euangelou. " Origins of the Greek Nation: The Byzantine Period, 1204-1461". Rutgers University Press, 1970. web link, p. 163, p. 330

- Turkish Language Association - TDK Online Dictionary. Yorouk Archived April 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, yorouk Archived April 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish)

- "yuruk." Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged. Merriam-Webster. 2002.

- Сима Ћирковић; Раде Михаљчић (1999). Лексикон српског средњег века. Knowledge. p. 645. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

Посебни санџак-бегови управљали су санџаци- ма који нису представљали територијалне, него само организационе јединице неких војничких и друштвених редова (војнуци, акинџије, Јуруци, Цигани)

- Aleksandar Matkovski (1983). Otpor na Makedonija vo vremeto na turskoto vladeenje. Misla. p. 372. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

Нај-голема организациона единица на таквите општествени редови како што биле војнуци, акинџии, Јуруци, Роми, Власи кои имале своја посебна организација и [...]

- Materialia Turcica, vol. 5-8, Studienverlag Brockmeyer., 1981, p.25

- Roux, Jean-Paul (1961). "La sédentarisation des nomades Yürük du vilayet d'Antalya". L'Ethnographie (in French). L'Entretemps éditions. 55: 67–68.

- Roux 1961, p. 68.

- Roux 1961, p. 66.

- Roux 1961, p. 68-69.

- Roux 1961, p. 75.

- Roux 1961, p. 69.

- Roux 1961, p. 70.

- Bourchier 1911, p. 217.

- Ethnic groups worldwide: a ready reference handbook By David Levinson page 41 :” Sarakatsani are Greek-speaking people in northwestern Greece and southern Bulgaria. They number less than 100 thousand , are ethnically Greek, speak Greek, and are Greek orthodox.”

- Kavadias, Georges B. (1965). Pasteurs-Nomades Mediterraneens: Les Saracatsans de Grèce (in French). Gauthier-Villars. p. 6. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

Gennep T, les considère (mais à titre d'hypothèse) comme des descendants des Turcs, installés dans le pays.

- Cusumano, Camille (2007). Greece, a Love Story. Seal Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-786-75058-0.

Legend tells us that the Sarakatsani, isolated for centuries in the mountains, are descended from the original Dorian Greeks.

- Dubin, Mark; Kydoniefs, Frank (2005). Greece. New Holland Publishers. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-860-11122-8.

...while the dialect of the Sarakatsani shepherds is said to be the oldest, a direct descendant of the language of the Dorian settlers.

- Kakouri, Katerina (1965). Death and resurrection. G. C. Elefteroudakis. p. 16.

Certain investigators fit them in with the archaic nomadic descent of the very ancient Dorians.

- Eliot, Alexander (1991). The penguin guide to Greece. Penguin Books. p. 318.

Fermor believes these nomads to be the direct, unalloyed descendants of the Dorians, whose geometric pottery designs are today mirrored in the weave of Sarakatsani textiles.

- Young, Kenneth (1969). The Greek passion. Dent. p. 12.

Leigh Fermor (1966) even suggests that Sarakatsani clothing, woven into 'black and white rectangles, dog-tooth staircases and saw-edges and triangles', resembles the designs on geometric pottery of the later Dorian period.

References

- Brailsford, H.N. Macedonia: Its Races and Their Future. Methuen & Co., London, 1906. Kailar Turks

- Cribb, Roger. Nomads in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Attribution

External links

| Look up yörük in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yörük. |