Zaza language

| Zaza | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Anatolia |

| Region | Main in Tunceli, Bingöl, Erzincan, Sivas, Elazığ, Erzurum, Malatya Gümüşhane Province, Şanlıurfa Province, and Varto, Adıyaman Province; diasporic in Mutki, Sarız, Aksaray, and Taraz |

| Ethnicity | Zaza |

Native speakers | 1.6 million (1998)[1] |

| Latin script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 |

zza |

| ISO 639-3 |

zza – inclusive codeIndividual codes: kiu – Kirmanjki (Northern Zaza)diq – Dimli (Southern Zaza) |

| Glottolog |

zaza1246[2] |

| Linguasphere |

58-AAA-ba |

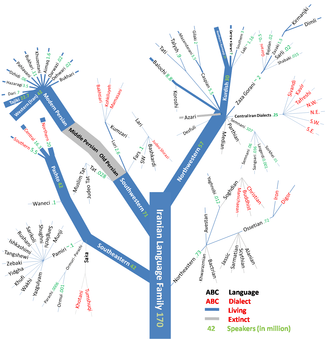

Zaza language, also called Zazaki, Kirmanjki and Dimli, is an Indo-European language spoken primarily in eastern Turkey by the Zazas. The language is a part of the northwestern group of the Iranian section of the Indo-European family, and belongs to the Zaza–Gorani and Caspian dialect group.[3] Zaza shares many features, structures, and vocabulary with Gorani. Zaza also has some similarities with Talyshi and other Caspian languages.[4] According to Ethnologue (which cites [Paul 1998]),[4] the number of speakers is between 1.5 and 2.5 million (including all dialects). According to Nevins, the number of Zaza speakers is between 2 and 4 million.[5]

Classification

Zaza belongs to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. From the point of view of the spoken language, its closest relatives are Gilaki, Mazandarani, Hewrami and other Caspian languages. The closest languages are genetically Hewrami and due to long-lasting influence Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish). However, the classification of Zaza has been an issue of political discussion. It is sometimes classified as a subdialect of Kurdish.[7][8][9][10] The majority of Zaza-speakers in Turkey identify themselves as ethnic Kurds.[11][12]

Zaza appears to be a pejorative name designating the language as a form of jibberish evident that its speakers designate their language as Dimlī or Kirmānd̲j̲kī.[13]

The US State Department "Background Note" lists the Zaza language as one of the major languages of Turkey, along with Turkish (official), Kurdish, Armenian, Greek, and Arabic.[14] Linguists connect the word Dimli with the Daylamites in the Alborz Mountains near the shores of the Caspian Sea in Iran and believe that the Zazas have immigrated from Deylaman towards the west. Zaza shows many connections to the Iranian languages of the Caspian region, especially the Gilaki language.

The Zaza language shows similarities with Hewrami or Gorani, Shabaki and Bajelani. However, it also shows many similarities with Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish), which it does not share with Caspian languages, Hewrami or other Kurdish languages:

- Similar personal pronouns

- Very similar ergative structure

- Masculine and feminine ezafe system

- Both languages have nominative and oblique cases that differs by masculine -î and feminine -ê

- Both languages have forgotten possesive enclitics, while it exists in other languages as Persian, Sorani, Gorani, Hewrami or Shabaki.

- Both languages distinguishes between aspirated and unaspirated voiceless stops.

- Similar vowel phonology

The Gorani, Bajelani, and Shabaki languages are spoken around the Iran-Iraq border; however, it is believed that speakers of these languages also migrated from Northern Iran to their present homelands.[citation needed] These languages are classified together in the Zaza–Gorani language group.

Dialects

There are three main Zaza dialects:

- Northern Zaza:[15] It is spoken in Tunceli, Erzincan, Erzurum, Sivas, Gumushane, Mus (Varto), Kayseri (Sariz) provinces.

Its subdialects are:

- West-Dersim[16]

- East-Dersim

- Varto

- Border dialects like Sarız, Koçgiri (Giniyan-idiom)

- Central Zaza: It is spoken in Elazığ, Bingöl, Solhan, Girvas and Diyarbakır provinces.

Its subdialects are:

- Bingol

- Palu

- Border dialects like Hani, Kulp, Lice, Ergani, Piran

- Southern Zaza:[17] It is spoken in Şanlıurfa (Siverek), Diyarbakır (Cermik, Egil), Adiyaman, Malatya provinces.

Its subdialects are:

- Siverek

- Cermik, Gerger

- Border dialects like Mutki and Aksaray

Literature and broadcast programs

The first written statements in Zaza were compiled by the linguist Peter Lerch in 1850. Two other important documents are the religious writings of Ehmedê Xasî of 1899,[18] and of Osman Efendîyo Babij[19] (published in Damascus in 1933 by Celadet Bedir Khan[20]); both of these works were written in the Arabic script.

The use of the Latin script to write Zaza became popular only in the diaspora in Sweden, France and Germany at the beginning of the 1980s. This was followed by the publication of magazines and books in Turkey, particularly in Istanbul. The efforts of Zaza intellectuals to advance the comprehensibility of their native language by using that alphabet helped the number of publications in Zaza multiply. This rediscovery of the native culture by Zaza intellectuals not only caused a renaissance of Zaza language and culture but it also triggered feelings among younger generations of Zazas (who, however, rarely speak Zaza as a mother tongue) in favor of this modern Western use of Zaza, rekindling their interest in their ancestral language.

The diaspora has also generated a limited amount of Zaza language broadcasting. Moreover, after restrictions were removed on local languages in Turkey during their move toward an eventual accession to the European Union, Turkish state-owned TRT Kurdî television launched several Zaza programs and a radio program on certain days.

Grammar

As with a number of other Indo-Iranian languages like Kurmanji and Sorani, Zaza features split ergativity in its morphology, demonstrating ergative marking in past and perfective contexts, and nominative-accusative alignment otherwise. Syntactically it is nominative-accusative.[21]

| English | Zazaki | Kurmanji |

|---|---|---|

| I see you | Ez to vînenu | Ez te dibînim |

| I saw you | Min ti dîyî | Min tu dîtî |

| You see me | Ti min vînenê | Tu min dibînî |

| You saw me | To ez dîyan | Te ez dîtim |

| Azad sees me | Azado min vîneno | Azad min dibîne |

| Azad saw me | Azadî ez dîyan | Azadî ez dîtim |

| I see Azad | Ez azadî vînenu | Ez azadî dibînim |

| I saw Azad | Min Azad dîyo | Min Azad dît |

Grammatical gender

Among all Western Iranian languages only Zaza and Kurmanji distinguish between masculine and feminine grammatical gender. Each noun belongs to one of those two genders. In order to correctly decline any noun and any modifier or other type of word affecting that noun, one must identify whether the noun is feminine or masculine. Most nouns have inherent gender. However, some nominal roots have variable gender, i.e. they may function as either masculine or feminine nouns.[22] This distinguishes Zaza from many other Western Iranian languages that have lost this feature over time.

For example, the masculine preterite participle of the verb kerdene ("to make" or "to do") is kerde; the feminine preterite-participle is kerdiye. Both have the sense of the English "made" or "done". The grammatical gender of the preterite-participle would be determined by the grammatical gender of the noun representing the thing that was made or done.

The linguistic notion of grammatical gender is distinguished from the biological and social notion of gender, although they interact closely in many languages. Both grammatical and natural gender can have linguistic effects in a given language.

Vocabulary

Words in Zaza can be divided into five groups in respect to their origins. Most words in Zaza are Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Indo-Iranian and Proto-Iranian in origin. The fourth group consists of words that developed when Zaza speakers divided from the Proto-Iranian language. The fifth group consists of loan words. Loan words in Zaza are chiefly from Arabic and Persian.

Phonological correspondences of Zaza and other Iranian languages

| PIE. | Old Persian | Pahlavi | Persian | Avestan | Parthian | Zaza | Kurdish dialects | English | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *ḱ | θ | h | h | s | s | s | s | - | |||

| māhīg | māhi | masya | māsyāg | māsa | māsî | fish | |||||

| *ǵ(h) | d | d | d | z | z | z | z | - | |||

| ǵno- | dān- | dān- | dān- | zān- | zān- | zān- | zān- | know | |||

| *kʷ | č | z | z | č | ž | j, ž, z | ž | - | |||

| *leuk- | raučah | rōz | ruz | raočah | rōž | roje, | rož | day | |||

| *gʷ | j | z | z | j | ž | j | ž | - | |||

| *gwen- | zan | zan | jaini | žan | jani | žin | woman | ||||

| *d(h)w- | duv- | d- | d- | dv- | b- | b- | d- | - | |||

| *d(h)war- | d u var- | dar | dar | d var- | bar | -bar | darî | door | |||

| *sw- | (h)uv- | xw- | x- | xv- | wx- | w- | xw- | - | |||

| *s wesor | x wāhar | xāhar | xvahar | w xar | wā | x weh | sister | ||||

| *-rd(h),*-ld(h) | -rd | -l | -l | -rd | -r(δ) | -r̄ | uncertain | - | |||

| *ḱered | θar(a)d- | sal | sāl | sarəδ- | sar ri | sāl | year | ||||

| *-rǵ(h),*-lǵ(h) | -rd | -l | -l | -rz | -rz | -rz | uncertain | - | |||

| hil- | hel- | harəz- | hir z- | ar z- (change of meaning) | hêl- | let | |||||

| *-m | -m | -m | -m | -m | -m | -m | -v/w | - | |||

| nomn̥ | nāman- | nām | nām | nāman- | nām | nāme | nāv, nāw | name | |||

| *w- | v- | w- | b- | v- | w- | v- | b- | - | |||

| *wīk'm̥tī | wīst | bist | vīsiti- | wīst | vist | bîst | twenty |

Alphabet

The Zazaki alphabet contains 31 letters:[23]

| Upper case | A | B | C | Ç | D | E | Ê | F | G | Ğ | H | I | İ | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | Ş | T | U | Û | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower case | a | b | c | ç | d | e | ê | f | g | ğ | h | ı | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | ş | t | u | û | v | w | x | y | z |

| IPA phonemes | a | b | dz, dʒ | ts, tʃ | d | ɛ | e | f | g | ʁ | h | ɪ | i | ʒ | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | ʃ | t | y | u | v | w | x | j | z |

References

- ↑ Zaza at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Kirmanjki (Northern Zaza) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Dimli (Southern Zaza) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Zaza". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Iranica Nevertheless, their language has preserved numerous isoglosses with the dialects of the southern Caspian region, and its place in the Caspian dialect group of Northwest Iranian is clear.

- 1 2 "The Position of Zazaki Among West Iranian languages by Paul Ludwig" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ Anand, Pranav; Nevins, Andrew. "Shifty Operators in Changing Contexts" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2005.

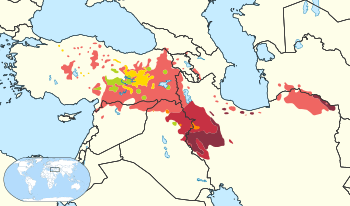

- ↑ The map shown is based on a map published by Le Monde Diplomatique in 2007. A similar map was made in 1998 by Mehrdad Izady (and labelled "for class use only"). The map is based on a twofold "North Kurdish" vs. "South Kurdish" division, and apparently conflates Central and Southern dialects. The area marked "Gorani" significantly overlaps with the areal of Southern Kurdish.

- ↑ "Kurdish language – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ According to the linguist Jacques Leclerc of Canadian "Laval University of Quebec, Zazaki is a part of Kurdish languages, Zaza are Kurds, he also included Goura/Gorani as Kurds

- ↑ T.C. Millî Eğitim Bakanlığı, Talim Ve Terbiye Kurulu Başkanlığı, Ortaokul Ve İmam Hatip Ortaokulu Yaşayan Diller Ve Lehçeler Dersi (Kürtçe; 5. Sınıf) Öğretim Programı, Ankara 2012, "Bu program ortaokul 5, 6, 7, ve 8. sınıflar seçmeli Kürtçe dersinin ve Kürtçe’nin iki lehçesi Kurmancca ve Zazaca için müşterek olarak hazırlanmıştır. Program metninde geçen “Kürtçe” kelimesi Kurmancca ve Zazaca lehçelerine birlikte işaret etmektedir."

- ↑ Prof. Dr. Kadrî Yildirim & Yrd. Doç. Dr. Abdurrahman Adak & Yrd. Doç. Dr. Hayrullah Acar & Zülküf Ergün & Îbrahîm Bîngol & Ramazan Pertev, Kurdî 5 – Zazakî, Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı, 2012

- ↑ "Is Ankara Promoting Zaza Nationalism to Divide the Kurds?". The Jamestown Foundation.

- ↑ Kaya, Mehmed S. (2011). The Zaza Kurds of Turkey: A Middle Eastern Minority in a Globalised Society. London: Tauris Academic Studies. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-84511-875-4.

- ↑ Paul, L. "Zaza". go.galegroup.com. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ↑ "The US State Department "Background Note" on Turkey". State.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ kiu

- ↑ Prothero, W. G. (1920). Armenia and Kurdistan. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 19.

- ↑ diq

- ↑ Xasi, Ehmedê (1899) Mewludê nebi, reprinted in 1994 in Istambul OCLC 68619349, (Poems about the birth of Mohammed and songs praising Allah.)

- ↑ Osman Efendîyo Babij kamo? (Who is the Osman Efendîyo Babij?)

- ↑ "Kırmancca (Zazaca) Kürtçesinde Öykücülüğün Gelişimi". zazaki.net.

- ↑ "Alignment in Kurdish: a diachronic perspective" (PDF). Kurdishacademy.org. 2004. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ↑ Todd, Terry Lynn (2008). A Grammar of Dimili (also Known as Zaza) (PDF). Electronic Publication. p. 33.

- ↑ "Zazaki alphabet". Zazaki.net. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

Literature

- Haig, Geoffrey. and Öpengin, Ergin. "Introduction to Special Issue Kurdish: A critical research overview" University of Bamberg, Germany

- Blau, Gurani et Zaza in R. Schmitt, ed., Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, ISBN 3-88226-413-6, pp. 336–40 (About Daylamite origin of Zaza-Guranis)

- Brigitte Werner. (2007) "Features of Bilingualism in the Zaza Community" Marburg, Germany

- Paul, Ludwig. (1998) "The Position of Zazaki Among West Iranian languages" University of Hamburg

- Larson, Richard. and Yamakido, Hiroko. (2006) "Zazaki as Double Case-Marking" Stony Brook University and University of Arizona.

- Lynn Todd, Terry. (1985) "A Grammar of Dimili" University of Michigan

- Mesut Keskin, Zur dialektalen Gliederung des Zazaki. Magisterarbeit, Frankfurt 2008. (PDF)

- Gippert, Jost. (1996) "Historical Development of Zazaki" University of Frankfurt

- Gajewski, Jon. (2004) "Zazaki Notes" Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

External links

| Zazaki edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Zaza language test of Wiktionary at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Kirmanjki test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zaza language. |

- Zaza People and Zazaki Literature

- News, Articles and Columns (in Zazaki)

- News, Folktales, Grammar Course (in Zazaki)

- News, Articles and Bingöl city (in Zazaki)

- Center of Zazaki (in Zazaki)(in German)(in Turkish)(in English)

- Zazaki Language Institute (in Zazaki)(in German)(in Turkish)

- Website of Zazaki Institute Frankfurt