Central Kurdish

| Central Kurdish | |

|---|---|

| Sorani | |

| سۆرانی، کوردیی ناوەندی | |

| |

| Native to | Kurdistan (Iraq and Iran) |

Native speakers | 10 million (5M in Iraq and 5M in Iran) (2014)[1] |

|

Indo-European

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Sorani alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Iraq[2] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

ckb |

| Glottolog |

cent1972[3] |

| Linguasphere |

58-AAA-cae |

| |

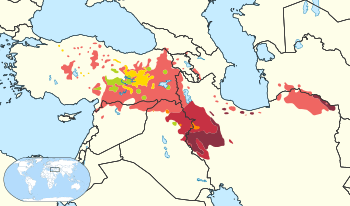

Central Kurdish (کوردیی ناوەندی, Kurdîy nawendî), also called Sorani (سۆرانی, Soranî) is a Kurdish language spoken in Iraq, mainly in Iraqi Kurdistan, as well as the Kurdistan Province, Kermanshah Province, and West Azerbaijan Province of western Iran. Central Kurdish is one of the two official languages of Iraq, along with Arabic, and is in political documents simply referred to as "Kurdish".[4][5]

The term Sorani, named after the former Soran Emirate, is used especially to refer to a written, standardized form of Central Kurdish written in the Sorani alphabet developed from the Arabic alphabet in the 1920s by Sa'íd Sidqi Kaban and Taufiq Wahby.[6]

History

Tracing back the historical changes that Central Kurdish has gone through is difficult. No predecessors of Kurdish languages are yet known from Old and Middle Iranian times. The extant Kurdish texts may be traced back to no earlier than the 16th century CE.[7]

The current status of Central Kurdish as a standardized written language can be traced back to late Ottoman era. In Sulaymaniyah (Silêmanî), the Ottoman Empire had created a secondary school, the Rushdiye, graduates from which could go to Istanbul to continue to study there. This allowed Central Kurdish, which was spoken in Silêmanî, to progressively replace Hawrami dialects as the literary vehicle for Kurdish.

Since the fall of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party – Iraq Region, there have been more opportunities to publish works in the Kurdish languages in Iraq than in any other country in recent times.[8] As a result, Central Kurdish has become the dominant written form of Kurdish.[9]

Writing system

Central Kurdish is written with a modified Arabic alphabet. However, the other main Kurdish language, Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji), which is spoken mainly in Turkey, is usually written in the Latin alphabet.

In the Sorani writing system almost all vowels are always written as separate letters. This is in contrast to the original Arabic writing system and most other writing systems developed from it, in which certain vowels (usually "short" vowels) are shown by diacritics above and under the letters, and usually omitted.

The other major point of departure of the Sorani writing system from other Arabic-based systems is that the Arabic letters that represent sounds that are non-existent in Sorani are usually (but not always) replaced by letters that better represent their Kurdish pronunciation.[10] The Arabic loanword طلاق (/tˤalaːq/ in Classical Arabic), for example, is usually written as تهلاق in Sorani, replacing the character for the pharyngealized sound /tˤ/ ("ط") with the character for /t/ ("ت"). Sorani also uses the four letters "گ" (/g/), "چ" (/t͡ʃ/), "پ" (/p/), and "ژ" (/ʒ/) which are used in the Persian alphabet but are absent in the original Arabic character inventory.

The Sorani writing system does not used the Tashdeed (gemination) diacritic found in the original Arabic writing system. Instead, in the few cases where double consonants are found, the consonant is simply written twice, as in شاڵڵا (IPA: /ʃɑɫɫɑ/, English:"God willing").

Demographics

The exact number of Sorani speakers is difficult to determine, but it is generally thought that Sorani is spoken by about 9 to 10 million people in Iraq and Iran.[11][12] It is the most widespread speech of Kurds in Iran and Iraq. In particular, it is spoken by:

- Around 5 million Kurds in Iranian Kurdistan. Located south of Lake Urmia that stretches roughly to the outside of Kermanshah.

- Around 5 million Kurds in Iraqi Kurdistan, including the Sorani tribe. Most of the Kurds who use it are found in the vicinity of Hewlêr (Erbil), Sulaymaniyah (Silêmanî), Kirkuk and Diyala Governorate.

Subdialects

Following includes the traditional internal variants of Sorani. However, nowadays, due to widespread media and communications, most of them are regarded as subdialects of standard Sorani:

- Mukriyani; The language spoken south of Lake Urmia with Mahabad as its center, including the cities of Piranshahr and the Kurdish speaking part of Naghadeh. This region is traditionally known as Mukriyan.

- Ardalani, spoken in the cities of Sanandaj, Saqqez, Marivan, Kamyaran, Divandarreh and Dehgolan in Kordestan province and the Kurdish speaking parts of Tekab and Shahindej in West Azerbaijan province. This region is known as Ardalan.

- Garmiani, in and around Kirkuk

- Hawlari, spoken in and around the city of Hawler (Erbil) in Iraqi Kurdistan and Oshnavieh. Its main distinction is changing the consonant /l/ into /r/ in many words.

- Babani, spoken in and around the city of Sulaymaniya in Iraq and the cities of Baneh, Bokan and Sardasht in Iran.

- Jafi, spoken in the towns of Javanroud, Ravansar and some villages around Sarpole Zahab and Paveh.

Media and education

Iraq is the only country in which a Kurdish language has enjoyed official or semi-official rights during the last few decades. Kurdish media outlets in Iraq mushroomed during the 1990s, spurred by the semi-autonomous status the region has enjoyed since the uprising against the Saddam regime in 1991.[13] The use of Kurdish in media and education is prevalent in Iraqi Kurdistan. Seven of the top 10 TV stations viewed by Iraqi Kurds are Kurdish-language stations,[14] and the use of Arabic in Kurdistan schools has decreased to the extent that the number of Iraqi Kurds who speak Arabic fluently has dropped significantly over the past decades.[15]

Some Kurdish media in Iraq seem to be aiming for constructing a cross-border Kurdish identity. The Kurdish-language satellite channel Kurdistan TV (KTV), owned by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), for example, employs techniques that expose audiences to more than one Kurdish variety in the same show or program.[16] It has been suggested that continuous exposure to different Kurdish varieties on KTV and other satellite television stations might make Kurdish varieties increasingly mutually intelligible.[16]

A recent proposal was made for Central Kurdish to be the official language of the Kurdistan Regional Government. This idea has been favoured by some Central Kurdish-speakers but has disappointed Northern Kurdish speakers.[17]

In Iran, state-sponsored regional TV stations air programs in both Kurdish and Persian. Kurdish press are legally allowed in Iran, but there have been many reports of a policy of banning Kurdish newspapers and arresting Kurdish activists.[18][19][20]

Phonology

Central Kurdish has 8 phonemic vowels and 26 to 28 phonemic consonants (depending on whether the pharyngeal sounds /ħ/ and /ʕ/ exist in the dialect or not).

Vowels

The following table contains the vowels of Central Kurdish.[21][10] Vowels in parentheses are not phonemic, but have been included in the table below because of their ubiquity in the language. Letters in the Sorani alphabet take various forms depending on where they occur in the word.[10] Forms given below are letters in isolation.

| IPA | Sorani Alphabet | Romanization | Example Word (Sorani) | Example Word (English) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | ى | î | hiʧ = "nothing" | "beet" |

| ɪ | - | i | gɪr'tɪn = "to take, to hold" | "bit" |

| e | ێ | e, ê | hez = "power" | "bait" |

| (ɛ) | ه | e | bɛjɑni = "morning" | "bet" |

| (ə) | ا ه | (mixed) | "but" | |

| æ | ه | â | tænæ'kæ = "tin can" | "bat" |

| u | وو | û | gur = "calf" | "boot" |

| ʊ | و | u | gʊɾg = "wolf" | "book" |

| o | ۆ | o | gor = "level" | "boat" |

| ɑ | ا | a | gɑ = "cow" | "balm" ("father") |

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Near-close | ɪ | ʊ | |

| Close-mid | e | o | |

| Mid | (ə) | ||

| Open-mid | (ɛ) | ||

| Near-open | æ | ||

| Open | a | ɑ |

Some Vowel Alternations and Notes

The vowel [æ] is sometimes pronounced as [ə] (the sound found in the first syllable of the English word "above"). This sound change takes place when [æ] directly precedes [w] or when it is followed by the sound [j] (like English "y") in the same syllable. If it, instead, precedes [j] in a context where [j] is a part of another syllable it is pronounced [ɛ] (as in English "bet").[10]

The vowels [o] and [e], both of which have slight off-glides in English, do not possess these off-glides in Sorani.

Consonants

Letters in the Sorani alphabet take various forms depending on where they occur in the word.[10] Forms given below are letters in isolation.

| IPA | Sorani Alphabet | Romanization | Example Word (Sorani) | Example Word (English) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | ب | b | بووڵ bûł (ashes) | b in "bat" | |

| p | پ | p | پیاو pyâw (man) | p in "pat" | |

| t | ت | t | تهمهن taman (age) | t in "tab" | |

| d | د | d | دهرگا dargâ (door) | d in "dab" | |

| k | ک | k | کهر kar (donkey) | c in "cot" | |

| g | گ | g | گهوره gawra (big) | g in "got" | |

| q | ق | q | قووڵ qûł (deep) | Like Eng. k but further back in the throat | |

| ʔ | ا | ' | ئاماده âmâda (ready) | middle sound in "uh-oh" | |

| f | ف | f | فنجان finjân (cup) | f in "fox" | |

| v | ڤ | v | گهڤزان gavzân (to roll over) | v in "voice" | |

| s | س | s | سوور sûr (red) | s in "sing" | |

| z | ز | z | زۆر zor (many) | z in "zipper" | |

| x | خ | kh | خهزر khazr (anger) | Like the ch in German "Bach" | |

| ʕ | ع | ` | عراق ‘irâq (Iraq) | Pharyngeal fricative (like Arabic "ain") | Presence of this is regional (mostly used in Iraqi dialects) |

| ɣ | غ | gh | پێغهمهر peghamar (prophet) | Like the sound above, but voiced | Mostly in borrowed words, usually pronounced [x] |

| ʃ | ش | sh | شار shâr (city) | sh in "shoe" | |

| ʒ | ژ | zh | ژوور zhûr (room) | ge in "beige" | |

| ʧ | چ | ch | چاک châk (good) | ch in "cheap" | |

| ʤ | ج | j | جوان jwân (beautiful) | j in "jump" | |

| ħ | ح | ḥ | حزب ḥizb (political party) | More guttural than the English h | Presence of this is regional (mostly used in Iraqi dialects) |

| h | ھ | h | ههز haz (desire) | h in "hat" | |

| m | م | m | مامر mâmir (chicken) | m in "mop" | |

| n | ن | n | نامه nâma (letter) | n in "none" | |

| w | و | w | ولات wiłât (country) | w in "water" | |

| j | ى | y | یانه yâna (club) | y in "yellow" | |

| ɾ | ر | r | رۆژ rozh (day) | t in Am. Eng. "water" | |

| r | ڕ | ř, rr | ئهمڕۆ amřo (today) | Like Spanish trilled r | |

| l | ل | l | لهت lat (piece) | l in "let" (forward in the mouth) | |

| ɫ | ڵ | ł | باڵ bâł (arm) | l in "all" (backward in the mouth) |

As in certain other Western Iranian languages (e.g. Kurmanji Kurdish), the two pharyngeal consonants /ħ/ and /ʕ/ exist in most Iraqi dialects of Central Kurdish. However, they are rare in the Iranian dialects of Central Kurdish.[22]

An important allophonic variation concerns the two velar sounds /k/ and /g/. Similar to certain other languages of the region (e.g. Turkish and Persian), these consonants are strongly palatalized before the close and mid front vowels (/i/ and /e/) in Central Kurdish.[23][24]

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t̪ | k | q | ʔ | |||||

| voiced | b | d̪ | g | ||||||||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡ʃ | |||||||||

| voiced | d͡ʒ | ||||||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ɬ | ʃ | x | ħ | h | |||

| voiced | (v) | z | ʒ | ɣ | (ʕ) | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n̪ | ŋ | ||||||||

| Approximant | l̪ | j | w | ||||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||||||

Syllable

Central Kurdish allows both complex onsets (e.g. spî: "white", kwer: "blind") and complex codas (e.g. farsh: "carpet"). However, the two members of the clusters are arranged in such a way that, in all cases, the Sonority Sequencing Principle (SSP) is preserved.[25] In many loanwords, an epenthetic vowel is inserted to resyllabify the word, omitting syllables that have codas that violate SSP. Originally mono-syllabic words such as /hazm/ ("digestion") and /zabt/ ("record") therefore become /ha.zim/ and /za.bit/ respectively.[25]

Primary stress always falls on the last syllable in nouns,[26] but in verbs its position differs depending on tense and aspect. Some have suggested the existence of an alternating pattern of secondary stress in syllables in Central Kurdish words.[26]

Grammar

Word order

The standard word order in Sorani is SOV (subject–object–verb).[27]

Nouns

Nouns in Sorani Kurdish may appear in three general forms. The Absolute State, Indefinite State, and Definite State.

Absolute State

A noun in the absolute state occurs without any suffix, as it would occur in a vocabulary list or dictionary entry. Absolute state nouns receive a generic interpretation,[21] as in "qâwa rash a." ("Coffee is black.") and "wafr spî a." ("Snow is white").[10]

Indefinite State

Indefinite nouns receive an interpretation like English nouns preceded by a, an, some, or any.

Several modifiers may only modify nouns in the indefinite state.[10] This list of modifiers includes:

- chand [ʧand] "a few"

- hamu [hamu] "every"

- chî [ʧi] "what"

- har [haɾ] "each"

- ... i zor [ɪ zoɾ] "many"

Nouns in the indefinite state take the following endings:[21][10]

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Noun Ending with a Vowel | -yek | -yân |

| Noun Ending with a Consonant | -ek | -ân |

A few examples are given below (from[10]) showing how nouns are made indefinite:

- پیاو pyâw 'man' > پیاوێک pyâwèk 'a man'

- نامه nâma 'letter' > نامهیهک nâmayèk 'a letter'

- پیاو pyâw 'man' > پیاوان pyâwân '(some) men'

- دهرگا dargâ 'door' > دهرگایان dargâyân '(some) doors'

Definite State

Definite nouns receive an interpretation like English nouns preceded by the.

Nouns in the definite state take the following endings:[21][10]

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Noun Ending with a Vowel | -ka | -kân |

| Noun Ending with a Consonant | -aka | -akân |

When a noun stem ending with [i] is combined with the definite state suffix the result is pronounced [eka] ( i + aka → eka)

Verbs

Like many other Iranian languages, verbs have a present stem and a past stem in Central Kurdish. The present simple tense, for example, is composed of the aspect marker "da" ("a" in Sulaymaniyah dialect) followed by the present stem followed by a suffixed personal ending. This is shown in the example below with the verb نووسین / nûsîn ("to write"), the present stem of which is نووس / nûs.

| Verb | Meaning |

|---|---|

| دهنووسم danûsim | I write |

| دهنووسی danûsî | You (sg.) write |

| دهنووسێ danûse | She/He/It writes |

| دهنووسین danûsîn | We write |

| دهنووسن danûsin | You (pl.) write |

| دهنووسن danûsin | They write |

Note that the personal endings are identical for the second person plural (Plural "you") and third person plural ("they").

Similarly, the simple past verb is created using the past stem of the verb. The following example shows the conjugation of the intransitive verb هاتن hâtin ("to come") in the simple past tense. The past stem of "hâtin" is "hât".

| Verb | Meaning |

|---|---|

| هاتم hâtim | I came |

| هاتی hâtî | You (sg.) came |

| هات hât | She/He/It came |

| هاتین hâtîn | We came |

| هاتن hâtin | You (pl.) came |

| هاتن hâtin | They came |

Central Kurdish is claimed by some to have split ergativity, with an ergative-absolutive arrangement in the past tense for transitive verbs.[10] Others, however, have cast doubt on this claim, noting that the Sorani Kurdish past may be different in important ways from a typical ergative-absolutive arrangement.[28][29] In any case, the transitive past tense in Sorani Kurdish is special in that the agent affix looks like the possessive pronouns and usually precedes the verb stem (similar to how accusative pronouns in other tenses). In the following example, the transitive verb نووسین / nûsîn ("to write") is conjugated in the past tense, with the object "nâma" ("letter"). The past stem of the verb is "nûsî". (from[10])

| Verb | Meaning |

|---|---|

| نامهم نووسی nâma-m nûsi | I wrote a letter. |

| نامهت نووسی nâma-t nûsi | You (sg.) wrote a letter. |

| نامهی نووسی nâma-y nûsi | She/He/It wrote a letter. |

| نامهمان نووسی nâma-mân nûsi | We wrote a letter. |

| نامهتان نووسی nâma-tân nûsi | You (pl.) wrote a letter. |

| نامهیان نووسی nâma-yân nûsi | They wrote a letter. |

Note in the example above that the clitics attaching to the objects are otherwise interpreted as possessive pronouns. The combination "nâma-m" therefore is translated as "my letter" in isolation, "nâma-t" as "your letter", and so on.

The agent affix is a clitic that must attach to a preceding word/morpheme. If the verb phrase has words other than the verb itself (as in the above example), it attaches to first word in the verb phrase. If no such pre-verbal matter exists, it attaches to the first morpheme of the verb. In the progressive past, for example, where the aspect marker "da" precedes the verb stem, the clitic attaches to "da". This is shown in the examples below with the verb "xwârdin" ("to eat"). (from[10])

- da-m xwârd (I was eating)

- da-t xwârd (You were eating)

Gender

Unlike Kurmanji Kurdish, there is not gender distinction in Central Kurdish. There are no pronouns to distinguish between masculine and feminine and no verb inflection to signal gender.[30]

Dictionaries and translations

There are a substantial number of Sorani dictionaries available, amongst which there are many that seek to be bilingual.

English and Sorani

- English–Kurdish Dictionary by Dr. Selma Abdullah and Dr. Khurhseed Alam

- Raman English-Kurdish Dictionary by Destey Ferheng

See also

Notes

- ↑ Central Kurdish at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ↑ "Full Text of Iraqi Constitution". Washington Post. 12 October 2005. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Central Kurdish". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Allison, Christine (2012). The Yezidi Oral Tradition in Iraqi Kurdistan. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-74655-0. "However, it was the southern dialect of Kurdish, Central Kurdish, the majority language of the Iraqi Kurds, which received sanction as an official language of Iraq."

- ↑ "Kurdish language issue and a divisive approach". Kurdish Academy of Language. 5 March 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- ↑ Blau, Joyce (2000). Méthode de Kurde: Sorani. Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-41404-4. , page 20

- ↑ electricpulp.com. "KURDISH LANGUAGE i. HISTORY OF THE KURDISH LA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- ↑ "Iraqi Kurds". Cal.org. Archived from the original on 2012-06-24. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ↑ "Language background of major refugee groups to the UK - Refugee Council". Languages.refugeecouncil.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Thackston, W.M. (2006). Sorani Kurdish: A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings.

- ↑ "Kurdistan Democratic Party-Iraq". Knn.u-net.com. Archived from the original on 2012-08-07. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ↑ SIL Ethnologue (2013) under "Central Kurdish" gives a 2009 estimate of 5 million speakers in Iraq and an undated estimate of 3.25 speakers in Iran.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS | World | Middle East | Guide: Iraq's Kurdish media". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- ↑ "BBG Research Series: Media consumption in Iraq". BBG. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- ↑ "Knowledge of Arabic Fading Among Iraq's Autonomous Kurds". Rudaw. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- 1 2 "Identity, language, and new media: The Kurdish case (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- ↑ "Kurdish language issue and a divisive approach | Kurdish Academy of Language". Kurdishacademy.org. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ↑ Ahmadzadeh, Hashem; Stansfield, Gareth (2010). "The Political, Cultural, and Military Re-Awakening of the Kurdish Nationalist Movement in Iran". Middle East Journal. 64 (1): 11–27. doi:10.2307/20622980. JSTOR 20622980.

- ↑ "– Media in Iran's Kurdistan". Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- ↑ "World Directory of Minorities" (PDF). www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/eoir/legacy/2014/02/19/Kurds.pdf. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Merchant, Livingston T. Introduction to Sorani Kurdish: The Principal Kurdish Dialect Spoken in the Regions of Northern Iraq and Western Iran. University of Raparin. ISBN 978-1483969268.

- ↑ Barry, Daniel (2016). "Kurmanji Kurdish Pharyngeals: Emergence and the Perceptual Magnet Effect" (PDF). Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ↑ "Portland State Multicultural Topics in Communications Sciences & Disorders | Kurdish". www.pdx.edu. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- ↑ Asadpour, Hima; Mohammadi, Maryam. "A Comparative Study of Kurdish Phonological Varieties" (PDF).

- 1 2 Zahedi, Muhamad Sediq; Alinezhad, Batool; Rezai, Vali (2012-09-26). "The Sonority Sequencing Principle in Sanandaji/Erdelani Kurdish: An Optimality Theoretical Perspective". International Journal of English Linguistics. 2 (5): 72. doi:10.5539/ijel.v2n5p72. ISSN 1923-8703.

- 1 2 Saadi Hamid, Twana A. (2015). The prosodic phonology of Central Kurdish (Ph.D.). Newcastle University.

- ↑ Soranî Kurdish, A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings, by W. M. Thackston

- ↑ Jügel, a.M, Thomas, Frankfurt (2009). "Ergative Remnants in Sorani Kurdish?" (PDF). OArSieJnÜtGalEiLa Suecana. LVIII: 142–158.

- ↑ Samvelian, P. "A lexicalist account of Sorani Kurdish prepositions." Proceedings of the HPSG07 Conference. Stanford: CSLI Publications. 2006.

- ↑ Kurdish Sorani language developmental features

References

- Hassanpour, A. (1992). Nationalism and Language in Kurdistan 1918–1985. USA: Mellen Research University Press.

- Nebez, Jemal (1976). Toward a Unified Kurdish Language. NUKSE.

- Izady, Mehrdad (1992). The Kurds: A Concise Handbook. Washington, D.C.: Taylor & Francis.

External links

| Central Kurdish edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- The New Testament in Soranî

- The Kurdish Academy of Language (unofficial)

- Working with Sorani Speaking Patients NHS (UK) Guide

- Discussion in Central Kurdish archived with Kaipuleohone