Gorani language

| Gorani | |

|---|---|

| گۆرانی | |

| Native to | Iraq and Iran |

| Region | Primarily Hawraman and Garmian |

Native speakers | 250,000 (2014)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

hac (ambiguous between Gorani and Hawrami) |

| Glottolog |

gura1251[2] |

| Linguasphere |

58-AAA-b |

| |

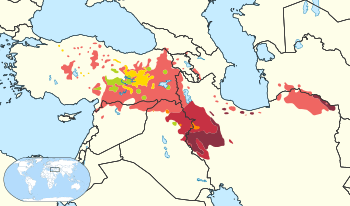

Gorani (also Gurani) is a group of Northwestern Iranian dialects spoken by groups of Iranian and Iraqi citizens in the southernmost parts of Iranian Kurdistan and the Iraqi Kurdistan region. It is classified as a member of the Zaza–Gorani branch of the Northwestern Iranian languages.[3]

The Hewramî dialect, although often considered a sub-dialect of Gorani,[4][5] is a very distinct dialect spoken by Gorani/Hewrami people in a region called Hewraman along the Iran–Iraq border, and is sometimes considered to be a distinct language.[6]

Gorani is spoken in the southwestern corner of province of Kurdistan and northwestern corner of province of Kermanshah in Iran, and in parts of the Halabja region in Iraqi Kurdistan and the Hawraman mountains between Iran and Iraqi Kurdistan.[7]

The oldest literary documents in these related languages, or dialects, are written in Gorani.

Many Gorani speakers belong to the religious grouping Yarsanism, with a large number of religious documents written in Gorani.

Gorani was once an important literary language in the parts of Western Iran but has since been replaced by Sorani.[8] In the 19th century, Gorani as a language was slowly replaced by Sorani in several cities, both in Iran and Iraq. Today, Sorani is the primary language spoken in cities including Kirkuk, Meriwan, and Halabja, which are still considered part of the greater Goran region.

Kurds and Gorani speakers themselves tend to consider Gorani as a dialect of Kurdish group of languages,[9][10][11][12] which diverged off from Kurmanji speakers, Badhini and Sorani alike, at around 100 BCE.[13] The differences between the Zaza–Gorani languages and the Kurdish languages are too many, and are therefore far too great by any standard linguistic criteria to warrant classification as dialects of the same languages.[13]

Etymology

The name Goran appears to be of Indo-Iranian origin. The name may be derived from the old Avestan word, gairi, which means mountain.[14] The word Gorani refers to inhabitants of the mountains or highlanders as the suffix -i means from. The word has been used to describe mountainous regions and the regions' communities in modern Kurdish literary texts. In this sense Gorani has the same etymological background as the Gorani language spoken in the Balkans, which derives from a Slavic word 'gora' also meaning mountainous region.

The name Horami is believed by some scholars to be derived from God's name in Avestan, Ahura Mazda.[15]

Literature

Under the independent rulers of Ardalan (9th–14th / 14th–19th century), with their capital latterly at Sanandaj, Gorani became the vehicle of a considerable corpus of poetry. Gorani was and remains the first language of the scriptures of the Ahl-e Haqq sect, or Yarsanism, centered on Gahvara. Prose works, in contrast, are hardly known. The structure of Gorani verse is very simple and monotonous. It consists almost entirely of stanzas of two rhyming half-verses of ten syllables each, with no regard to the quantity of syllables.

An example: دیمای حمد ذات جهان آفرین

"After praise of the Being who created the world

یا وام پی تعریف شای خاور زمین

I have reached a description of the King of the Land of the East.

Names of forty classical poets writing in Gurani are known, but the details of the lives and dates are unknown for the most part. Perhaps the earliest writer is Mala Parisha, author of a masnavi of 500 lines on the Shi'ite faith who is reported to have lived around 1398–99. Other poets are known from the 17th–19th centuries and include Mahzuni, Shaikh Mostafa Takhti, Khana Qubadi, Yusuf Zaka, and Ahmab Beg Komashi. One of the last great poets to complete a book of poems (divan) in Gurani is Mala Abd-al Rahm of Tawa-Goz south of Halabja.

There exist also a dozen or more long epic or romantic masnavis, mostly translated by anonymous writers from Persian literature including: Bijan and Manijeh, Khurshid-i Khawar, Khosrow and Shirin, Layla and Majnun, Shirin and Farhad, Haft Khwan-i Rostam and Sultan Jumjuma. Manuscripts of these works are currently preserved in the national libraries of Berlin, London, and Paris.

Some Gorani literary works:

- Shirin u Xusrew by Khana Qubadi (lived 1700–1759), published 1975 in Bagdad.

- Diwan des Feqe Qadiri Hemewend, 19th century

- The Quran, translated in the 20th century by Haci Nuri Eli Ilahi (Nuri Eli Shah).

Hawrami

Hawrami (هەورامی; Hewramî) also known as Avromani, Awromani or Owrami, is one of the main groups of dialects of the Gorani language, and is regarded as the most archaic of the Gorani group.[16] It is mostly spoken in the Hawraman region, a mountainous region located in western Iran (Iranian Kurdistan) and northeastern Iraq (Iraqi Kurdistan). The key cities of this region are Pawe in Iran and Halabja in Iraq. Hawrami is sometimes called Auramani or Horami by people foreign to the region.

Gorans

There are also large communities of people of Ahl-e Haqq in some regions of Iranian Azerbaijan. The town of Ilkhichi (İlxıçı), which is located 87 km south west of Tabriz is almost entirely populated by Yâresânis. But they are ethnically Turks. Groups with similar beliefs also exist in Iranian Kurdistan. Both the Dersim (Zazaki) people and the Gorani people, adhere to a form of Yazdanism. These people are called under the various names, such as Ali-Ilahis and Ahl-e Haqq. Groups with similar beliefs also exist in all parts of Kurdistan.

See also

References

- ↑ Gorani at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Gurani". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ J. N. Postgate, Languages of Iraq, ancient and modern, British School of Archaeology in Iraq, [Iraq]: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2007, p. 138.

- ↑ D. N. Mackenzie, Avromani, Encyclopedia Iranica

- ↑ D. N. Mackenzie, GURĀNI, Encyclopedia Iranica

- ↑ "A Comprehensive study of Hawrami Kurdish : UNESCO-CULTURE". Archived from the original on 2008-08-15.

- ↑ "Kurdish language." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 23 Nov. 2010

- ↑ Meri, Josef W. Medieval Islamic Civilization: A–K, index. p 444

- ↑ "Kurdish Nationalism and Competing Ethnic Loyalties", Original English version of: "Nationalisme kurde et ethnicités intra-kurdes", Peuples Méditerranéens no. 68–69 (1994), 11-37

- ↑ Kehl-Bodrogi, Krisztina. "Syncretistic religious communities in the Near East: Collected Papers of the International Symposium, Alevism in Turkey and Comparable Syncretistic Religious Communities in the Near East in the Past and Present”, Berlin, 14–17 April 1995

- ↑ Ozoglu, Hakan. "Kurdish notables and the Ottoman state." Albany: State University of New York Press, 2004

- ↑ Romano, David. "The Kurdish nationalist movement: opportunity, mobilization, and identity." Cambridge. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- 1 2 Izady, Mehrdad R. (1992). The Kurds: A concise Handbook. London: Taylor and Francis. p. 170.

- ↑ Peterson, Joseph H. "Avestan Dictionary".

- ↑ Nyberg, H.S. (1923), The Pahlavi documents of Avroman, Le Monde Oriental, XVII, p.189.

- ↑ D. N. Mackenzie Avromani, Encyclopedia Iranica

Textbooks

- D.N.MacKenzie (1966). The Dialect of Awroman (Hawraman-i Luhon). Kobenhavn. THE DIALECT OF AWROMAN

External links

| Gorani language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- The Dialect of Awroman( Hawraman-i Luhon) by D.N.MacKenzie

- Gorani Influence on Central Kurdish: Substratum or Prestige Borrowing? by Michiel Leezenberg, University of Amsterdam

- Ergativity and Role-Marking in Hawrami by Anders Holmberg, University of Newcastle & CASTL and David Odden, Ohio State University

- The Noun Phrase in Hawrami by Anders Holmberg, University of Newcastle & CASTL and David Odden, Ohio State University