The Holocaust in the Independent State of Croatia

The Holocaust in the Independent State of Croatia refers primarily to the genocide of Jews, but sometimes also include that of Serbs (the "Serbian Genocide") and Romani (Porajmos), during World War II within the Independent State of Croatia, a fascist puppet state ruled by the Ustashe regime, that included most of the territory of modern-day Croatia, the whole of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina and the eastern part of Syrmia (Serbia). 90% of Croatian Jews were exterminated in Ustashe-run concentration camps like Jasenovac and others, while a considerable number of Jews were rounded up and turned over by the Ustashe for extermination in Nazi Germany.

Background

On 25 March 1941, Prince Paul of Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact, allying the Kingdom of Yugoslavia with the Axis powers. Prince Paul was overthrown, and a new anti-German government under Peter II and Dušan Simović took power. The new government withdrew its support for the Axis, but did not repudiate the Tripartite Pact. Nevertheless, Axis forces, led by Nazi Germany invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941.

The Independent State of Croatia was proclaimed by the Ustaše - a Croatian fascist, racist, ultra-nationalist and terrorist organization - on 10 April 1941. Within the new state lived approximately 40,000 Jews, only 9,000 of whom would ultimately survive the war.[1]

Already prior to the war the Ustaše forged close ties to fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. In 1933 the Ustaše presented "The Seventeen Principles", which proclaimed the uniqueness of the Croatian nation, promoted collective rights over individual rights, and declared that people who were not Croat by race and blood, would be excluded from political life. In 1936, the Ustaše leader, Ante Pavelić, wrote in "The Croat Question":

″Today, practically all finance and nearly all commerce in Croatia is in Jewish hands. This became possible only through the support of the state, which thereby seeks, on one hand, to strengthen the pro-Serbian Jews, and on the other, to weaken Croat national strength. The Jews celebrated the establishment of the so-called Yugoslav state with great joy, because a national Croatia could never be as useful to them as a multi-national Yugoslavia; for in national chaos lies the power of the Jews... In fact, as the Jews had foreseen, Yugoslavia became, in consequence of the corruption of official life in Serbia, a true Eldorado of Jewry...The entire press in Croatia is also in Jewish-masonic hands…" [2]

The Holocaust

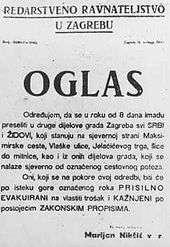

Anti-Semitic legislation and start of persecution

The main race laws in the Independent State of Croatia were adopted and signed by the Ustaše leader Ante Pavelić on 30 April 1941: the "Legal Decree on Racial Origins" (Zakonska odredba o rasnoj pripadnosti) and the "Legal Decree on the Protection of Aryan Blood and the Honour of the Croatian People" (Zakonska odredba o zaštiti arijske krvi i časti hrvatskog naroda).[3] The "Legal Decree on the Nationalization of the Property of Jews and Jewish Companies" was declared on 10 October 1941.

Actions against Jews began immediately after the Independent State of Croatia was founded. On 10–11 April 1941 a group of prominent Jews in Zagreb was arrested by the Ustaše and held for ransom. On 13 April the same was done in Osijek, where Ustaše and Volksdeutscher mobs destroyed the synagogue and Jewish graveyard.[4] This procedure was repeated in 1941 and 1942 several times with groups of Jews.

Anti-Semitic propaganda

The Ustaše immediately initiated intensive anti-Semitic propaganda. A day after the signing of the main race laws on 30 April 1941, the newspaper of the Ustaše movement, Hrvatski narod (Croatian Nation), published across its entire front page: "The Blood and Honor of the Croatian people protected by special provisions".[5]

Two days later, the newspaper Novi list concluded that Croatians must "be more alert than any other ethnic group to protect their racial purity, ... We need to keep our blood clean of the Jews". The newspaper also wrote that Jews are synonymous with "treachery, cheating, greed, immorality and foreigness", and therefore "wide swaths of the Croatian people always despised the Jews and felt towards them natural revulsion".[5] Nova Hrvatska (New Croatia) added that according to the Talmud, "this toxic. hot well-spring of Jewish wickedness and malice, the Jew is even free to kill Gentiles".[5]

One of the main claims of Ustaše propaganda was that the Jews have always been against an independent Croatian state and against the Croatian people. In April 1941 the newspaper Hrvatski narod (The Croatian People) accused Jews of being responsible for the "many failures and misfortunes of so many Croatian people", which led the Poglavnik [the Ustaše leader Ante Pavelic] to "eradicate these evils".[5] A Spremnost article stated that the Ustaša movement defines "Judaism as one of the greatest enemies of the people".[5]

Some in the Catholic Church joined the anti-Semitic propaganda. Thus the Catholic Bishop of Sarajevo, Ivan Šarić, published in his diocesan newspaper that "the movement to free the world of Jews, represents the movement for the restoration of human dignity. Omniscient and omnipotent God is behind this movement ".[6] And in July 1941, the Franciscan priest, Dionysius Juričev, in Novi list wrote that "it is no longer a sin to kill a seven year-old child".[7]

Ustaše concentration camps

Already in April 1941 the Ustaše established the concentration camps Danica[8] (near Koprivnica), Kruščica concentration camp near Travnik[9] and Kerestinec, where along with communists and other political opponents, the Ustaše imprisoned Jews.

In May 1941, the Ustaše rounded up 165 Jewish youth in Zagreb, ages 17–25, most of them members of the Jewish sports club Makabi, and sent them to the Danica concentration camp (all but 3 were killed by the Ustaše).[10]

In May and June the Ustaše established new camps, primarily for Jews who came to Croatia as refugees from Germany and countries which Germany had previously occupied, and some of these were quickly killed. Also arrested and sent to the Ustaše camps were larger groups of Jews from Zagreb (June 22), Bihac (June 24), Karlovac (June 27), Sarajevo, Varaždin, Bjelovar, etc.

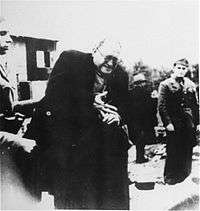

On 8 July 1941 the Ustaše ordered that all arrested Jews be sent to Gospić, from where they took the victims to death camps Jadovno on Velebit, and Slano on the island of Pag,[11] where they carried out mass executions. The historian Paul Mojzes lists 1,998 Jews, 38,010 Serbs, and 88 Croats killed at Jadovno and related execution grounds,[12] among them 1,000 children.

Other sources generally offer a range of 10,000–68,000 deaths at the Jadovno system of camps, with estimates of the number of Jewish deaths ranging from several hundred[12] to 2,500–2,800.[13]

In August 1941 the Ustaše established the Jasenovac concentration camp, one of the largest in Europe.[14] This included the Stara Gradiška concentration camp for women and children. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington, D.C. presently estimates that the Ustaša regime murdered between 77,000 and 99,000 people in Jasenovac system of camps between 1941 and 1945.[15] The Jasenovac Memorial Site quotes a similar figure of between 80,000 and 100,000 victims.[16] Of these, the United States Holocaust Museum says that at least 20.000 were Jews.

The Jasenovac Memorial site lists the individual names of 83,145 victims, including 13,116 Jews, 16,173 Roma, 47,627 Serbs, 4,255 Croats, 1,128 Bosnian Muslims,[17] etc. Of the total 83,145 named Jasenovac victims, 20,101 were children under the age of 12, and 23,474 were women.[17]

Other events

The destruction of the Sephardi Il Kal Grande synagogue in Sarajevo was carried out by Nazi German soldiers and their local Ustaše allies soon after their arrival in the city on 15 April.[18] The Sarajevo Haggadah was the most important artifact which survived this period, smuggled out of Sarajevo and saved from the Nazis and Ustaše by the chief librarian of the National Museum, Derviš Korkut. The demolition of the Zagreb Synagogue was ordered by the Ustaše mayor Ivan Werner and was carried out from 10 October 1941 to April 1942. The two Jewish football clubs in the state, ŽGiŠK Makabi Zagreb and ŽŠK Makabi Osijek, were banned in 1941.[19]

In April 1942, the Jews of Osijek were forced to build a "Jewish settlement" at Tenja, into which they were herded along with Jews from the surrounding region. Approximately 3,000 Jews were moved to Tenja in June and July 1942.[3] From Tenja, 200 Jews were transported to the Jasenovac concentration camp and 2,800 Jews were transported to the Auschwitz concentration camp.[3]

In February 1942 the Ustaše Interior Minister, Andrija Artuković, in a speech to the Croatian Parliament declared that:

- "The Independent State of Croatia through its decisive action has solved the so-called Jewish question ... This necessary cleansing procedure finds its justification not only from a moral, religious and social point of view, but also from the national-political point of view: it is international Jewry associated with international communism and Freemasonry, that sought and still seeks to destroy the Croatian people".[20] The speech was accompanied by shouts of approval -" yes! - from the parliamentary benches.[20]

On 5 May 1943, Nazi SS leader Heinrich Himmler paid a short visit to Zagreb in which he held talks with Ante Pavelić.[21] Starting on 7 May, a roundup of the remaining Jews in Zagreb was carried out by the Gestapo under the command of Franz Abromeit.[22] During this period, Archbishop Stepinac offered the head rabbi in Zagreb Miroslav Šalom Freiberger help to escape the roundup, which he ultimately declined.[23] The operation lasted for the following week, and resulted in the capture of 1,700 Jews from Zagreb and 300 from the surrounding area. All of these people were taken to the Auschwitz concentration camp.[24]

After the capitulation of Italy on 8 September 1943, Nazi Germany annexed the Croat-populated Italian provinces of Pula and Rijeka into its Operational Zone Adriatic Coast. On 25 January 1944, the Germans demolished the Jewish synagogue in Rijeka.[24] The region of Međimurje had been annexed by the Kingdom of Hungary in 1941. In April 1944, the Jews of Međimurje were taken to a camp in Nagykanizsa where they were held until their transport to Auschwitz. An estimated 540 Međimurje Jews were murdered at Auschwitz, while 29 were murdered at Jasenovac.[25]

Other ethnicities

Serbs

Many historians describe the Ustasha regime's mass killings of Serbs as meeting the definition of genocide.[26][27][28][29][30] Some racist laws, brought from Germany, in addition to Jews and Roma, were applied to the Serbs. Vladimir Žerjavić estimates that 322,000 Serbs were killed in the Independent State of Croatia, out of a total population of 1.8 million Serbs. Thus one in six Serbs were killed, which represents the highest percentage killed in Europe, after the Jews and Roma. Of these Žerjavić estimates that about 78,000 Serbs were killed at Jasenovac and other Ustasha camps. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., between 320,000 and 340,000 Serbs were killed in the NDH.

Roma

The Ustasha regime launched the persecution of the Roma in May 1942. Whole families were arrested and transported to the Jasenovac concentration camp, where they were immediately, or within a few months, killed. Estimates of the number of victims vary from 16,000 (this figure is given Vladimir Žerjavić) to 40,000. The Jasenovac Memorial at Jasenovac, Croatia lists the names of 16,173 Roma killed at that concentration camp. Due to their way of life, many more victims are probably unrecorded. The German historian Alexander Korb and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., both estimate at least 25,000 casualties among the Roma, which represents nearly the total Roma population in the Independent State of Croatia.

Abolition of racial laws

On 5 May 1945, the Legal Decree on the Equalization of Members of the NDH Based on Racial Origin (Zakonska odredba o izjednačavanju pripadnika NDH s obzirom na rasnu pripadnost) was declared which repealed the racial laws enacted over the course of the war.

Number of victims

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

| Issues |

| Genocide of indigenous peoples |

|

European colonization of the Americas

|

| Soviet genocide |

| Nazi Holocaust and genocide (1941–1945) |

| Cold War |

|

| Contemporary genocide |

|

| Related topics |

| Category |

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum lists the following number of victims in the Independent State of Croatia:

- 32,000 Jews,[15] with 12,000 to 20,000 Jews killed at the Jasenovac system of camps[31]

- At least 25,000 Roma, or virtually the entire Roma population in the Independent State of Croatia[31]

- Between 320,000 and 340,000 Serbs, most killed by the Ustasha authorities[31]

Slavko Goldstein estimates that approximately 30,000 Jews were killed from the Independent State of Croatia, with approximately 12,790 of those killed in Croatia. Vladimir Žerjavić's demographics research produced an estimate of 25,800 to 26,700 Jewish victims, of which he estimates that 19,000 were killed by the Ustasha in Croatia and Bosnia, and the rest abroad.[32]

By site

The Jasenovac Memorial Site maintains the names of 13,116 Jews killed at the Jasenovac concentration camp.[17]

Concentration camps

- Jadovno concentration camp

- Jasenovac concentration camp

- Sisak children's concentration camp

- Stara Gradiška concentration camp

- Lobor concentration camp

- Sajmište concentration camp (run by German forces in Serbia)

- Tenja concentration camp

Notable people

Victims

- Lea Deutsch, Croatian Jewish child actress

- Kalmi Baruh, Bosnian Jewish scholar

- Laura Papo Bohoreta, Bosnian Jewish feminist writer and Ladino scholar

- Sava Šumanović, Serb painter

Survivors

Other

Righteous among the Nations

Over one hundred Croatians have been recognized as Righteous among the Nations. They include Žarko Dolinar and Mate Ujević.

See also

References

- ↑ Goldstein, Ivo. Croatia: A History, C. Hurst & Co. Ltd., London, 1999. (p. 136)

- ↑ Ante Pavelic: The Croat Question |http://chnm.gmu.edu/history/faculty/kelly/blogs/h312/wp-content/sources/pavelic.pdf

- 1 2 3 Živaković-Kerže, Zlata. Od židovskog naselja u Tenji do sabirnog logora

- ↑ "Jewish Virtual Library".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Boško Zuckerman, "Prilog proučavanju antisemitizma i protužidovske propagande u vodećem zagrebačkom ustaškom tisku (1941-1943)" Zavod za hrvatsku povijest, vol 42, Zagreb (2010).

- ↑ Phayer 2000, p. 35.

- ↑ Phayer 2000, p. 34.

- ↑ Despot, Zvonimir. "Kako je osnovan prvi ustaški logor u NDH". Vecernji list.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin (January 2002). The Routledge Atlas of the Holocaust. Psychology Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-415-28145-4.

Kruscica concentration camp set up in April 1941

- ↑ "HAPŠENJE 165 JEVREJSKIH OMLADINACA U ZAGREBU U MAJU 1941. GODINE".

- ↑ "Concentration camp "Uvala Slana", Pag island". Archived from the original on 2014-04-07.

- 1 2 Mojzes 2011, p. 60.

- ↑ Mojzes 2009, p. 160.

- ↑ Pavlowitch 2008, p. 34.

- 1 2 "Jasenovac". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ↑ Official website of the Jasenovac Memorial Site

- 1 2 3 "Poimenični Popis Žrtava KCL Jasenovac 1941-1945" [List of Individual Victims KCL Jasenovac 1941-1945] (in Croatian). Spomen podrucje Jasenovac Memorial Site.

- ↑ Never-ending story of the Sarajevo Haggadah

- ↑ Nogometni leksikon, Miroslav Krleža Lexicographical Institute, Zagreb, 2004 (p. 307)

- 1 2 "'U NDH je rješeno židovsko pitanje'". Jutarnji list. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ Goldstein, Ivo. Holokaust u Zagrebu, Novi liber, Zagreb, 2001. (p. 475)

- ↑ Goldstein, Ivo. Holokaust u Zagrebu, Novi liber, Zagreb, 2001. (p. 470)

- ↑ Goldstein, Ivo. Holokaust u Zagrebu, Novi liber, Zagreb, 2001, p. 472.

- 1 2 Krizman, Narcisa Lengel. Antisemitizam Holokaust Antifašizam, Studia Iudaico-Croatica, Zagreb, 1996, p. 256.

- ↑ Sudbina međimurskih Židova, povijest.net; accessed 23 October 2016.

- ↑ Ivo Goldstein. "Uspon i pad NDH". Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ↑ Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons (1997). Century of genocide: critical essays and eyewitness accounts. p. 430. ISBN 0-203-89043-4. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ↑ "Mesić: Jasenovac je bio poprište genocida, holokausta i ratnih stratišta" (in Croatian). Index.hr. 30 April 2006. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ↑ Helen Fein, Accounting for Genocide, New York, The Free Press, 1979, pg. 79, 105

- ↑ Robert M. Hayden. "Independent State of Croatia". e-notes. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Zerjavic, Vladimir. "YUGOSLAVIA-MANIPULATIONS -WITH THE NUMBER OF SECOND WORLD WAR VICTIMS". Croatian Information Center. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

Sources

- Bartulin, Nevenko (2008). "The Ideology of Nation and Race: The Croatian Ustasha Regime and its Policies toward the Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia 1941-1945". Croatian Studies Review. 5: 75–102.

- Bulajić, Milan (1992). Tudjman's "Jasenovac Myth": Ustasha Crimes of Genocide. Belgrade: The Ministry of information of the Republic of Serbia.

- Bulajić, Milan (1994). Tudjman's "Jasenovac Myth": Genocide against Serbs, Jews and Gypsies. Belgrade: Stručna knjiga.

- Bulajić, Milan (1994). The Role of the Vatican in the break-up of the Yugoslav State: The Mission of the Vatican in the Independent State of Croatia. Ustashi Crimes of Genocide. Belgrade: Stručna knjiga.

- Bulajić, Milan (2002). Jasenovac: The Jewish-Serbian Holocaust (the role of the Vatican) in Nazi-Ustasha Croatia (1941-1945). Belgrade: Fund for Genocide Research, Stručna knjiga.

- Cvetković, Dragan (2011). "Holokaust u Nezavisnoj Državi Hrvatskoj - numeričko određenje" (PDF). Istorija 20. veka: Časopis Instituta za savremenu istoriju. 29 (1): 163–182.

- Dedijer, Vladimir (1992). The Yugoslav Auschwitz and the Vatican: The Croatian Massacre of the Serbs During World War II. Amherst: Prometheus Books. ISBN 9780879757526.

- Hory, Ladislaus; Broszat, Martin (1964). Der kroatische Ustascha-Staat1941-1945. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

- Kolstø, Pål (2011). "The Serbian-Croatian Controversy over Jasenovac". Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 225–246. ISBN 9780230347816.

- Korb, Alexander (2010). "A Multipronged Attack: Ustaša Persecution of Serbs, Jews, and Roma in Wartime Croatia". Eradicating Differences: The Treatment of Minorities in Nazi-Dominated Europe. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 145–163. ISBN 9781443824491.

- Levy, Michele Frucht (2011). "'The Last Bullet for the Last Serb': The Ustaša Genocide against Serbs: 1941–1945". Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responses. Routledge. pp. 54–84. ISBN 9781317986829.

- Lituchy, Barry M., ed. (2006). Jasenovac and the Holocaust in Yugoslavia: Analyses and Survivor Testimonies. New York: Jasenovac Research Institute. ISBN 9780975343203.

- McCormick, Robert B. (2014). Croatia Under Ante Pavelić: America, the Ustaše and Croatian Genocide. London-New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Mojzes, Paul (2008). "The Genocidal Twentieth Century in the Balkans". Confronting Genocide: Judaism, Christianity, Islam. Lanham: Lexington Books. pp. 151–182.

- Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the 20th Century. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Novak, Viktor (2011). Magnum Crimen: Half a Century of Clericalism in Croatia. 1. Jagodina: Gambit.

- Novak, Viktor (2011). Magnum Crimen: Half a Century of Clericalism in Croatia. 2. Jagodina: Gambit.

- Paris, Edmond (1961). Genocide in Satellite Croatia, 1941-1945: A Record of Racial and Religious Persecutions and Massacres. Chicago: American Institute for Balkan Affairs.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Phayer, Michael (2000). The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Phayer, Michael (2008). Pius XII, the Holocaust, and the Cold War. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Rivelli, Marco Aurelio (1998). Le génocide occulté: État Indépendant de Croatie 1941–1945 [Hidden Genocide: The Independent State of Croatia 1941–1945] (in French). Lausanne: L'age d'Homme.

- Rivelli, Marco Aurelio (1999). L'arcivescovo del genocidio: Monsignor Stepinac, il Vaticano e la dittatura ustascia in Croazia, 1941-1945 [The Archbishop of Genocide: Monsignor Stepinac, the Vatican and the Ustaše dictatorship in Croatia, 1941-1945] (in Italian). Milano: Kaos.

- Rivelli, Marco Aurelio (2002). "Dio è con noi!": La Chiesa di Pio XII complice del nazifascismo ["God is with us!": The Church of Pius XII accomplice to Nazi Fascism] (in Italian). Milano: Kaos.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Yeomans, Rory (2013). Visions of Annihilation: The Ustasha Regime and the Cultural Politics of Fascism, 1941-1945. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Holocaust in Croatia. |

- Holocaust Era in Croatia at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum