Theresienstadt concentration camp

| Theresienstadt concentration camp | |

|---|---|

| Concentration camp | |

|

Theresienstadt concentration camp archway with the phrase Arbeit macht frei (work makes (you) free), placed over the entrance in a number of Nazi concentration camps | |

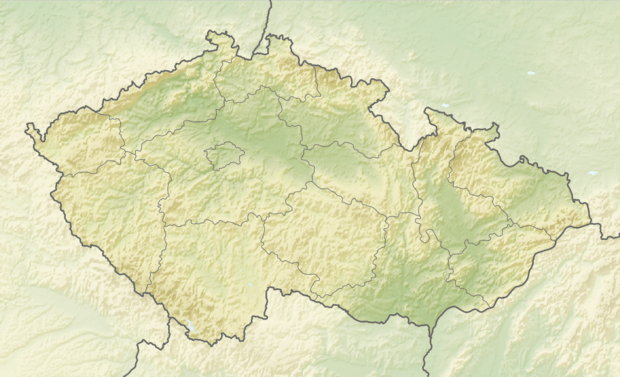

Location of Theresienstadt concentration camp within Czech Republic | |

| Coordinates | 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E / 50.51333°N 14.16694°E |

| Other names | Czech: Koncentrační tábor Terezín, German: KZ Theresienstadt |

| Location | Terezín, Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia |

| Built by | Holy Roman Empire |

| Operated by | Nazi Germany |

| Original use | Fort |

| Operational | 10 June 1940–8 May 1945 |

| Inmates |

Ghetto: Jews Small fortress: political |

| Number of inmates |

144,000 Jews 90,000 political prisoners |

| Killed |

33,000 at the ghetto 2,600 at the small fortress |

| Liberated by | Soviet Union |

| Notable inmates | H. G. Adler, Ludwig Czech, Viktor Frankl, Petr Ginz, Richard Glazar, Fredy Hirsch, Egon Lánský, Arnošt Lustig, Zuzana Růžičková |

| Notable books | I Never Saw Another Butterfly, War and Remembrance, Way to Heaven |

Theresienstadt concentration camp, also referred to as Theresienstadt ghetto,[1][2][3] was a concentration camp established by the SS during World War II in the garrison city of Terezín (German: Theresienstadt), located in German-occupied Czechoslovakia.

Tens of thousands of people died there, some killed outright and others dying from malnutrition and disease. More than 150,000 other persons (including tens of thousands of children) were held there for months or years, before being sent by rail transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in occupied Poland, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere.[4]

History

The fortress of Theresienstadt in the north-west region of Bohemia was constructed between the years 1780 and 1790 on the orders of the Holy Roman emperor Joseph II. It was designed as part of a projected but never fully realised fort system of the monarchy, another piece being the fort of Josefov. Theresienstadt was named for the mother of the emperor, Maria Theresa of Austria, who reigned as archduchess of Austria in her own right from 1740 until 1780. By the end of the 19th century, the facility was obsolete as a fort; in the 20th century, the fort was used to accommodate military and political prisoners.

From 1914 until 1918, Gavrilo Princip was imprisoned here, after his conviction for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife on June 28, 1914, a catalyst for World War I. Princip died in Cell Number 1 from tuberculosis on April 28, 1918. In that year Theresienstadt would become part of the new state of Czechoslovakia and renamed Terezín.

After Germany invaded and occupied Czechoslovakia, on June 10, 1940, the Gestapo took control of Terezín and set up a prison in the "Small Fortress" (kleine Festung, the town citadel on the east side of the Ohře river). The first inmates arrived June 14. By the end of the war, the small fortress had processed more than 32,000 prisoners, of whom 5,000 were female; they were imprisoned for varying sentences. The prisoners were predominantly Czech at first, and later other nationalities were imprisoned there, including citizens of the Soviet Union, Poland, Germany, and Yugoslavia. Most were political prisoners.[5]

By November 24, 1941, the Nazis adapted the "Main Fortress" (große Festung, i.e. the walled town of Theresienstadt), located on the west side of the river, as a ghetto.[5] Jewish survivors have recounted the extensive work they had to do for more than a year in the camp, to try to provide basic facilities for the tens of thousands of people who came to be housed there.

From 1942, the Nazis interned the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia, elderly Jews and persons of "special merit" in the Reich, and several thousand Jews from the Netherlands and Denmark. Theresienstadt thereafter became known as the destination for the Altentransporte ("elderly transports") of German Jews, older than 65. Although in practice the ghetto, run by the SS, served as a transit camp for Jews en route to extermination camps, it was also presented as a "model Jewish settlement" for propaganda purposes.[6][7] The Nazis deported 42,000 people, mostly Czech Jews, from Theresienstadt in 1942, of whom only 224 survivors are known.[8]

On 11 November 1943, commandant Anton Burger ordered the entire camp population, approximately 40,000 people at that time, to stand in freezing weather during a camp census (sometimes referred to as the "Bohušovicer Kessel Census"). About 300 prisoners died of hypothermia as a result.[9]

Among the western European Jews deported to the camp were 456 Jews from Denmark, sent to Theresienstadt in 1943. They had been unable to escape to neutral Sweden in time before the Nazis started the deportation. Included also in the transports were European Jewish children whom Danish organisations had tried to conceal in foster homes. The arrival of the Danes was significant, as their government gained access to the ghetto for the International Red Cross in 1944, to view conditions there. (This took place after the D-Day Invasion of Normandy by the Allies). Most European governments, when occupied by the Nazis, had not tried to protect their fellow Jewish citizens. Historians believe the Germans were trying to keep the Danes satisfied as they had impressed many of their workers in war factories.

During a 1944 Red Cross visit, and in a propaganda film, the Nazis presented Theresienstadt to outsiders as a model Jewish settlement, but it was a concentration camp. More than 33,000 inmates died as a result of malnutrition, disease, or the sadistic treatment by their captors.[10] Whereas some survivors claimed the prison population reached 75,000 at one time, according to official records, the highest figure reached (on September 18, 1942) was 58,491. They were crowded into barracks designed to accommodate 7,000 combat troops.[11]

In the autumn of 1944, the Nazis began the liquidation of the ghetto, deporting more prisoners to Auschwitz and other camps; in one month, they deported 24,000 victims[12] (about 18,000 in 11 transports between 28 September and 28 October).

On 5 February 1945, SS chief Heinrich Himmler allowed a transport of 1,210 Jews, most of them from the Netherlands, from Theresienstadt to freedom in neutral Switzerland. Himmler and Jean-Marie Musy, a pro-Nazi former Swiss president, had arranged the transport. Jewish organisations working in Switzerland deposited a ransom of $1.25 million in Swiss banks for the Germans.

As the war turned against Nazi Germany, the Danish king Christian X secured the release of the Danish internees from Theresienstadt on April 15, 1945. The White Buses, organised in cooperation with the Swedish Red Cross, collected the 413 who had survived and took them home.

In April 1945, after the Dutch Jews had been transported to Switzerland, the International Red Cross visited the camp twice. The relief agency took over administration of the camp on 2 May 1945, as Soviet troops approached from the east.[13] Commandant Rahm and the rest of the SS fled on 5–6 May. On 8 May 1945, Terezín was liberated by Soviet troops.

Small Fortress

The "Small Fortress" (Malá pevnost in Czech, Kleine Festung in German) was part of the fortification on the east side of the river Ohře. It was separate from and unrelated to the Jewish ghetto in the main fortress on the river's west side. Beginning in 1940, the Gestapo used it as a prison, the largest in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The first inmates arrived on June 14, 1940. By the end of the war, 32,000 prisoners, of whom 5,000 were female, passed through the Small Fortress; most were usually deported later to a concentration camp.

Main fortress

In the spring of 1942, the Nazis expelled the 7,000 non-Jewish Czechs living in Terezín, and closed off the town. The Nazis established the ghetto and concentration camp in the main fortress on the east side of the river.

SS-Hauptsturmführer Siegfried Seidl[14] served as the first camp commandant, beginning in 1941. Seidl oversaw the labour of 342 Jewish artisans and carpenters, known as the Aufbaukommando, who converted the fortress into a concentration camp. Although the Aufbaukommando were promised that they and their families would be spared transport, this exemption was revoked during the fall 1944 liquidation.[15]

Command and control authority

The camp, Theresienstadt/Terezin, was a hybrid of ghetto and concentration camp, (KZ), with features of both. It was established by order of the SS-Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) in 1941 and administered by its GESTAPO Amt of the RSHA, Department IV-B-4, (Jews), headed by Eichmann who oversaw the ghetto and its SS-Commandant; he, in turn, was in charge of the daily ghetto administration, the SS officers, about 12, and the Czech gendarmes, who collaborated with the Germans; these last two were in charge of security and guard duties. An internal police force, run by Jewish inmates, answered directly to the Jewish self-administration and indirectly to the SS-commandant. Theresienstadt was also the only KZ excluded from the control of SS-Wirtschafthauptamt (main economic administration office) under Pohl and was classified as "concentration camp, class 4" (mildest). Pohl and the SS-Wirtschafthauptamt were in control of all concentration camps except Theresienstadt.

Gestapo and Sicherheitsdienst oversaw the day-to-day operations of the Kleine Festung, (Small Fortress), a prison of the Prague Gestapo which was controlled by the 'Higher SS and Police Führer', (HSSPF), Karl Frank, who reported directly to Himmler rather than the Office of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, a civilian department.

SS-Hauptsturmführer Ernst Möhs (1898–1945) was Eichmann's liaison-officer in Theresienstadt. During the camp's operations, three officers served as camp commandant: Siegfried Seidl, Anton Burger, and Karl Rahm.

Internal organisation

As in other European ghettos, the Nazis required the Jews to select a Jewish Council, which nominally governed the ghetto. In Theresienstadt, this was known as the "Cultural Council"; later it was called the "Jewish self-government of Theresienstadt".[16] The first of the Jewish elders of Theresienstadt was Jakob Edelstein, a Polish-born Zionist and former head of the Prague Jewish community. He served until 1943, when he was deported to Auschwitz and shot to death after being forced to watch the executions of his wife and son.[17]

The second was Paul Eppstein, a sociologist originally from Mannheim, Germany. Earlier, Eppstein was the speaker of the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland, the central organisation of Jews in Nazi Germany. He served until the autumn of 1944, when he was allegedly shot in the Small Fortress on Yom Kippur.

Benjamin Murmelstein, a rabbi from Vienna, had been part of the Cultural Council in Vienna after the Anschluss. As in other cities, the Jews were charged by the Nazis with organising actions in the Jewish community, including selection of people for transport when the Germans decided to deport them, beginning in 1942. Murmelstein was also deported to Theresienstadt. In late 1944, he succeeded Eppstein. He and other Jewish elders have been extremely controversial figures, condemned for years for what was seen as their collaboration with the Nazis. The Last of the Unjust, released in 2013, is a documentary centring on interviews with Murmelstein that were filmed by Claude Lanzmann in 1975, during the production of his masterwork Shoah. The interviews were not used in the earlier film.[18][19]

In the last days of the ghetto, Jiří Vogel of Prague served as the elder. From 1943 to 1945, Leo Baeck was the speaker of the Council of Elders of Theresienstadt. Before being deported to the camp from Berlin, he had served as the head of the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland. He survived Theresienstadt, and emigrated to London after the war.[20]

Industrial labour

Theresienstadt was used to supply the German war effort with a source of Jewish slave labour. Their major contribution was the splitting of local ore mined from Czechoslovakian mica. Blind prisoners were often spared deportation by assignment to this task. Others manufactured boxes or coffins, or sprayed military uniforms with a white dye to provide camouflage for German soldiers on the Russian front. According to ex-prisoners, Theresienstadt was also a sorting and re-distribution centre for underwear and clothing confiscated from Jews:

... from all parts of Germany, the baggage taken away from the Jews was sent to Theresienstadt, and there it was packaged, sorted-out in order to be sent out all over the country, to various cities, for the people who were bombed-out and suffered a shortage of underwear and clothing.[16]

Improvements made by inmates

Survivor Friedrich Schlaefrig described in 1946 how the early residents of Theresienstadt, with the assistance of the Germans, overcame the lack of water to the town:

We had no water system in Theresienstadt ... a number of wells were contaminated in a short time with typhoid fever. That was the reason that we had to close a number of wells, and had to undertake to extend the existing water pipe system. That was really a great piece of public works created under Jewish inventiveness and by Jewish labor. They expanded the water supply system, and have achieved [a condition] that we not only produced for the people good drinking water or, at least, not objectionable drinking water, but that also the toilet installations could be flushed with water, so that these unhygienic conditions were removed ... The Germans have permitted it, and we even obtained through them the material, because otherwise it would have been impossible ...[16]

After this, a fire department was established, made up of Jewish prisoners, with an acting fire chief. They relied on the newly constructed water system. Constructing the water system was only part of the major work undertaken by Jews, in what was called the technical service, in the first year of the camp. They had to make many more changes to buildings to adapt the fortress and barracks for the overcrowded conditions that the Germans imposed.[16]

Unequal treatment of prisoners

After the changes and sprucing up to prepare for the Red Cross visit, in the spring of 1944, the Gestapo screened the Jews of Theresienstadt, classifying them according to social prominence. Many of the "Prominente" were profiled, with photographs, among a collection of documents smuggled out after the liberation.[21]

The Gestapo reassigned some 150 to 200 prominent individuals to single rooms that would be shared by only two people, so that a husband and wife could live by themselves. Several members of the Cultural Council were included among the Prominente, due to the influence of Benjamin Murmelstein, then the "Jewish elder" of Theresienstadt. Former prisoners suggested in statements that those who held positions of authority practised nepotism, trying to protect individuals close to them, while struggling to avoid deportation and death in the closing days of the war. Murmelstein and other members of the Cultural Council were still deported in the final liquidation, but he and some others survived the war.[16]

Cultural activities and legacy

Theresienstadt was originally designated as a model community for middle-class Jews from Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Austria. Many educated Jews were inmates of Theresienstadt. In a propaganda effort designed to fool the western allies, the Nazis publicised the camp for its rich cultural life. In reality, according to a Holocaust survivor, "during the early period there were no [musical] instruments whatsoever, and the cultural life came to develop itself only ... when the whole management of Theresienstadt was steered into an organized course."[16]

The community in Theresienstadt tried to ensure that all the children who passed through the camp continued with their education. The Nazis required all camp children over a certain age to work, but accepted working on stage as employment. The prisoners achieved the children's education under the guise of work or cultural activity. Daily classes and sports activities were held. The community published a magazine, Vedem. The history of the magazine was studied and narrated by the Italian writer Matteo Corradini in his book La repubblica delle farfalle (The Republic of the Butterflies). Sir Ben Kingsley read that novel, speaking on 27 January 2015 during the ceremony held at Theresienstadt to mark International Holocaust Memorial Day.

Ilse Weber, a noted Czech Jewish poet, writer and musician for children, was held in the camp from February 1942, and worked as a night nurse in the camp's children's infirmary. She volunteered to join a transport of children to Auschwitz in November 1944, where she, her son Tommy, and all the children with her were murdered in the gas chambers immediately on arrival.

Conductor Rafael Schächter was among those held at the camp, and he formed an adult chorus. He directed it in a performance of the massive and complex Requiem by Giuseppe Verdi. Schächter conducted 15 more performances of the work before he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.[22]

Violinist Julius Stwertka, a former leading member of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and co-leader of the Vienna Philharmonic, died in the camp on 17 December 1942.

Pianist Alice Herz-Sommer (held with her son, Raphael Sommer) performed 100 concerts while imprisoned at Theresienstadt. She and Edith Steiner-Kraus, her friend and colleague, both survived the camp, emigrated to Israel after the war, and became professors of music, Herz-Sommer at the Jerusalem Academy of Music, and Steiner-Kraus at the Tel Aviv Academy of Music.[23]

In March 2012, a biography of Herz-Sommer was published.[24] At the time of her death in London at age 110 in 2014, Herz-Sommer was the oldest known Holocaust survivor.[25]

Martin Roman and Coco Schumann were part of the jazz band Ghetto Swingers. Artist and art teacher Friedl Dicker-Brandeis created drawing classes for children in the ghetto, among whom were Hana Brady ("Hana's suitcase"). They produced more than 4,000 drawings, which she hid in two suitcases before she was deported to Auschwitz in the final liquidation. The collection was preserved from destruction, and was discovered a decade later. Most of these drawings can now be seen at the Jewish Museum in Prague, whose archive of the Holocaust section administers the Terezín Archive Collection. Others are on display at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. The children of the camp also wrote stories and poems. Some were preserved and later published in a collection called I Never Saw Another Butterfly, its title taken from a poem by young Jewish Czech poet Pavel Friedman. He had arrived at Terezín on 26 April 1942, and later murdered at Auschwitz.

Painter Malva Schalek (Malvina Schalkova) was deported to Theresienstadt in February 1942. She produced more than 100 drawings and watercolours portraying life in the camp. On 18 May 1944, due to her refusal to paint the portrait of a collaborationist doctor, she was deported to Auschwitz, where she was murdered.[26]

Artist and architect Norbert Troller produced drawings and watercolours of life inside Theresienstadt, to be smuggled to the outside world. When the Gestapo found out, he was arrested and deported to Auschwitz, where he was liberated by the Russians in 1945. His memoirs and two dozen of his artworks were published in 1991.[27]

Composer Viktor Ullmann was interned in September 1942, and died at Auschwitz in October 1944. He composed some twenty works at Theresienstadt, including the one-act opera Der Kaiser von Atlantis (The Emperor of Atlantis or The Refusal of Death). It was planned for performance at the camp, but the Nazis withdrew permission when it was in rehearsal, probably because the authorities perceived its allegorical intent. The opera was first performed in 1975, and shown in full on BBC television in Britain. It continues to be performed.

Music composed by inmates is featured in Terezín: The Music 1941–44, a two-CD set released in 1991.[28][29] The collection features music composed mostly in 1943 and 1944 by Pavel Haas, Gideon Klein, Hans Krása, and Viktor Ullmann while interned at Theresienstadt. Haas, Krása, and Ullmann died in Auschwitz concentration camp in 1944, and Klein died in Fürstengrube in 1945.[30]

In 2007, the album Terezín – Theresienstadt of music composed at Theresienstadt was released by the Swedish singer Anne Sofie von Otter, assisted by baritone Christian Gerhaher, pianists, and chamber musicians. In 2008, Bridge Records released a recital by Austrian baritone Wolfgang Holzmair and American pianist Russell Ryan that drew on a different selection of songs.

Culture as Survival

Scholars have interpreted acts of cultural expression through theater, music, and art in Theresienstadt as a strategy for survival by those deported there. The ghetto became the site of a wide variety of works of art using different artistic mediums, from lectures to drawings, and devoted to a variety of themes.[31] At first, cultural activities were suppressed by the Nazis, but when the function of the ghetto as a model became clearer in 1942, these activities were deemed acceptable.[2] The Nazis decided that Theresienstadt could function uniquely as a place to deport member of Europe’s cultural elite.[32] At this time the Freizeitgestaltung (Association of Free Time Activities) was established, and cultural activities were allowed by the Nazis. However, instruments had previously been smuggled into Theresienstadt since 1941, and many artists considered them to be among their most basic needs.[33] Children in the ghetto expressed themselves and their reactions to their circumstances through drawings in the lessons permitted by the Nazis.[2] With these outlets, the people attempted to create a sense of hope within the ghetto.[34]

In Theresienstadt, cultural production thrived much more than in the Protectorate. Art in the ghetto underwent drastic development as it allowed for depiction and representation of true life in Theresienstadt.[2] The artwork provided the people with an artistic outlet through which they could express their feelings of defiance.[35] Despite constant deportations of inmates to the East, the ghetto inhabitants remained determined to continue performing and creating. Places in casts often needed to be reassigned as participants were deported.[2] The people remained strong willed in their persistence to create, as it helped them remain hopeful and live a more humane existence.[2] Rafael Schachter was one of the pioneering members of cultural activity in Theresienstadt. In the early days of Theresienstadt’s cultural activity, Schachter included a satirical sketch in his first performance.[36] Later in his time in Theresienstadt, Schachter put together a rendition of Verdi’s Requiem. In this version of Requiem, Schachter changed the ending notes to communicate a resistance signal. Adolf Eichmann and other important Nazi leaders were in the audience for a performance of Schachter’s Requiem, and Eichmann specifically enjoyed this version of the piece.[37] The Nazi’s didn't understand the underlying meanings of the change to Requiem or many other works performed in the ghetto.[38]

On September 23, 1943, the first performance of the children’s show Brundibar appeared in Theresienstadt. The show was performed fifty five times, and was the most successful show of all of the productions ever performed in the ghetto. Cast members were replaced as they were deported, but the show's main acts remained the same throughout the duration of the performances.[39] Brundibar’s original composer Hans Krasa composed a new score for the show in Theresienstadt as the original score had been lost, and the show was put together by Rudolf Freudenfeld under the supervision and tutelage of Rafael Schachter.[40] For the Theresienstadt performances of the show, poet Emil A. Saudek changed the ending lines from the original version to emphasize a political meaning behind the show. It was clear to the audience that the show’s main antagonist represented Hitler, but the Nazi’s themselves did not realize the hidden meaning in Brundibar, and even had the show presented during a visit by the Red Cross.[41] Brudibar was the top musical performance ever performed at Theresienstadt.[42]

Emperor of Atlantis was another opera produced in Theresienstadt. The opera was created by Peter Kien and Viktor Ullmann, who created the opera in the form of a legend so that they could include hidden meaning that would be missed by the Nazi’s.[43] Ullman strategically used music to include undertones with resistance implications, including artistic manipulation of Deutchland Uber Alles, and a secondary version of sheet music, with less direct implications than the version that was actually rehearsed, was handed over to the Nazi.[44] Ultimately, Emperor of Atlantis was never performed at Theresienstadt, although scholars differ on their reasoning as to why the opera never reached performance. The show may have ended before being performed because the Nazi’s in control of the ghetto saw the allegorical connection to Hitler and Nazi Germany in the opera’s plot line.[45] Alternatively, some scholars say the show never reached performance because of deportation to Auschwitz.[46]

Scholar’s views vary on Nazi reaction to the production of Theresienstadt’s cultural works. Some say the Nazis remained indifferent to the work that was composed and sung inside the ghetto.[2] Others say that the Nazis encouraged the artistic production, as the SS thought that nothing from Theresienstadt would ever reach outside of the ghetto.[47]

Use as propaganda tool

Late in the war, after D-Day and the invasion of Normandy, the Nazis permitted representatives from the Danish Red Cross and the International Red Cross to visit Theresienstadt in order to dispel rumours about the extermination camps. The commission that visited on June 23, 1944, included Swiss Red Cross representative Maurice Rossel, E. Juel-Henningsen, the head physician at the Danish Ministry of Health, and Franz Hvass, the top civil servant at the Danish Foreign Ministry. Dr. Paul Eppstein was instructed by the SS to appear in the role of the mayor of Theresienstadt.[48]

Weeks of preparation preceded the visit. The area was cleaned up, and the Nazis deported many Jews to Auschwitz to minimise the appearance of overcrowding in Theresienstadt. Also deported in these actions were most of the Czechoslovak workers assigned to "Operation Embellishment". The Nazis directed the building of fake shops and cafés to imply that the Jews lived in relative comfort. The Danes whom the Red Cross visited lived in freshly painted rooms, not more than three in a room. Rooms viewed may have included the homes of the "prominent" Jews of Theresienstadt, who were afforded the special privilege of having as few as two occupants to a room.[16] The guests attended a performance of a children's opera, Brundibár, which was written by inmate Hans Krása. The Red Cross representatives were conducted on a tour following a predetermined path designated by a red line on a map. The representatives apparently did not attempt to divert from the tour route on which they were led by the Germans, who posed questions to the Jewish residents along the way. If the representatives asked residents questions directly, they were ignored, in accordance with the Germans' instructions to the residents prior to the tour. Despite this, the Red Cross apparently formed a positive impression of the town.[16]

Following the successful use of Theresienstadt as a supposed model internment camp during the Red Cross visit, the Nazis decided to make a propaganda film there. It was directed by Jewish prisoner Kurt Gerron, an experienced director and actor; he had appeared with Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel. Shooting took eleven days, starting September 1, 1944.[49] After the film was completed, the director and most of the cast were deported to Auschwitz. Gerron was murdered by gas chamber on 28 October 1944.[50]

The film was intended to show how well the Jews were living under the purportedly benevolent protection of the Third Reich. If taken at face value, it documents the Jews of Theresienstadt living a relatively comfortable existence within a thriving cultural centre and functioning successfully during the hardships of World War II. They had to comply and perform according to Nazi orders. Often called The Führer Gives a Village to the Jews, the correct name of the film is Theresienstadt. Ein Dokumentarfilm aus dem jüdischen Siedlungsgebiet ("Terezin: A Documentary Film of the Jewish Resettlement").[lower-alpha 1] As the film was not completed until near the end of the war, it was never distributed as intended, although a few screenings were held. Most of the film was destroyed, but some footage has survived.

Statistics

Approximately 144,000 Jews were sent to Theresienstadt. Most inmates were Czech Jews, but 40,000 were from Germany, 15,000 from Austria, 5,000 from the Netherlands, and 300 from Luxembourg. In addition to the group of approximately 500 Jews from Denmark, Slovak and Hungarian Jews were deported to the ghetto. 1,200 Jewish children from the Białystok Ghetto in Poland were sent to Theresienstadt for six weeks before deportation to Auschwitz; none survived. About a quarter of the inmates (33,000) died in Theresienstadt, mostly because of the deadly conditions, which included hunger, stress, and disease. The typhus epidemic at the very end of war took an especially heavy toll.

About 88,000 prisoners were deported to Auschwitz and other extermination camps, including Treblinka. At the end of the war, 17,247 had survived. An estimated 15,000 children lived in the ghetto. Willy Groag, one of the youth care workers, mistakenly claimed after the war that only 93 survived.[52]

Allied prisoners of war

During the war, Allied prisoners of war (POWs) who repeatedly attempted to escape from POW camps were sent to Theresienstadt as punishment. 21 British, 21 New Zealand, and 17 Australian POWs were held there.[53] Keeping POWs from signatory countries of the Geneva Convention in such camp conditions was a war crime. Many of the survivors suffered chronic physical and mental health problems for most of their lives.[53]

In 1964, Germany paid the British government £1 million as reparation for the illegal transfer of British POWs to Theresienstadt.[53] Britain made no provision for dominion troops. For many years, the governments of Australia and New Zealand denied that any of their servicemen had been held at the camp. In 1987, Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke established a committee of investigation. It confirmed that POWs were held at Theresienstadt. The government then authorised payments of A$10,000 each to the Australian survivors of the camp. The New Zealand government also arranged for compensation for the New Zealand survivors.[53]

Postwar trials

- The first commandant of the camp, Captain Siegfried Seidl, was assigned to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp after leaving Theresienstadt, and later served as a staff officer with Adolf Eichmann during the slaughter of Hungary's 600,000 Jews.[12] After the war, he was convicted of war crimes by the Volksgericht, the Austrian People's Court established to prosecute Nazi war crimes,[54] and executed on 4 February 1947.[55]

- The camp's second commandant, Anton Burger, was tried in absentia by a Czech court in Litoměřice and sentenced to death in 1947. However, Burger escaped in June before the sentence could be carried out. He was arrested again in 1951 and escaped a second time. He eventually settled in Essen, where he lived under a false name until his death in December 1991.[13][56]

- The camp's third commandant, Karl Rahm, was captured by American forces in Austria and extradited to Czechoslovakia in 1947. On 30 April 1947, he was found guilty of crimes against humanity[57] in a Czech court, and executed four hours later.[58]

- The Czech gendarmerie commander, Theodor Janecek, died in prison in 1946 while awaiting trial.[13]

- A Czech court in Litoměřice found Miroslaus Hasenkopf, a camp perimeter guard, guilty of treason and sentenced him to 15 years imprisonment. Hasenkopf died in prison in 1951.[13]

- Anton Malloth, a prison guard at the Small Fortress, was arrested on 25 May 2000—more than 50 years after the war ended. He was convicted in 2001 of beating at least 100 prisoners to death, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

See also

Notes

- ↑ cf. Hans Sode-Madsen: The Perfect Deception. The Danish Jews and Theresienstadt 1940–1945, Leo Baeck Yearbook, 1993

References

- ↑ Karny, Miroslav, ed. (1995). Terezínska Pametni Kniha (Terezínska Iniciativa ed.). Prague: Melantrich.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chladkova, Ludmila (2005). The Terezín Ghetto. Památnik Terazin. pp. 29–30. ISBN 8086758192. OCLC 62324320.

- ↑ Benes, Frantisek; Tosnerova, Patricia (1996). Mail Service in the Ghetto Terezín 1941–1945. Prague: Profil.

- ↑ "1941:Mass Murder". The Holocaust Chronicle. p. 282. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

- 1 2 "Theresienstadt". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ "The Holocaust – The Ghettos – Theresienstadt". Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ "Museumspädagogik – Angebote für Schulen – Reise ohne Wiederkehr – Deportationsziel Theresienstadt" (in German). Stadt Coesfeld-Stadtmuseum "DASTOR". Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ "Theresienstadt: Key Dates". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ↑ "Zählung im Bohušovicer Kessel", ghetto-theresienstadt.info; accessed 24 September 2017.

- ↑ Schumacher, Claude (1998). Staging the Holocaust: The Shoah in Drama and Performance. Cambridge University Press. p. 155.

- ↑ Redlich (1992).

- 1 2 "Eichmann's Orders to Hang Jews Presented at His Trial in Jerusalem", JTA, 19 May 1961; accessed 22 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Theresienstadt: Final Weeks, Liberation, and Postwar Trials". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ↑ "Theresienstadt – einige wichtige Tatsachen". Archived from the original on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ↑ "The Aufbaukommando". Terezín Initiative. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "David P. Boder Interviews Friedrich Schlaefrig". Voices of the Holocaust. Paris, France. August 23, 1946. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ Friedländer, Saul (2009). Nazi Germany and the Jews: The Years of Persecution, 1933–1939. HarperCollins. p. 410. ISBN 978-0-06-135027-6. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ↑ Nelson, Rob (25 May 2013). "'The Last of the Unjust' Review: Claude Lanzmann's Rewarding Holocaust Documentary". Variety. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Richard Brody (24 May 2012). "Claude Lanzmann's Upcoming Film". Front Row. The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 2012-05-29. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ Baker, Leonard (1978). Days of Sorrow and Pain, Leo Baeck and the Berlin Jews. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Das Theresienstadt-Konvolut, ghetto-theresienstadt.de; accessed 24 September 2017.(in German)

- ↑ Bret McCabe (Winter 2012). "May it go to the heart". Johns Hopkins Magazine. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ↑ Berkley, George E. (2002). Hitler's Gift: Story of Theresienstadt. p. 262. ISBN 978-0828320641.

- ↑ Stoessinger, Caroline (2012). A Century of Wisdom: Lessons from the Life of Alice Herz-Sommer, the World's Oldest Living Holocaust Survivor. ISBN 978-0812992816.

- ↑ Mark Memmott (24 February 2014). "Oldest-Known Holocaust Survivor Dies; Pianist was 110". NPR. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ↑ Schalek, Malva. "Theresienstadt pictures". Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ↑ Troller, Norbert (1991). Theresienstadt: Hitler's gift to the Jews. University of North Carolina Press.

- ↑ Campbell, R.M. (11 November 1999). "Holocaust Musicians Left Powerful Legacy". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Seattle, WA. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ Stearns, David Patrick (28 January 1995). "Testament of Terezín". The Independent. London, UK. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ "Terezín – The Music 1941–44". Ciao. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ Blodig, Vojtech & White, Joseph Robert (2012). "Terezin" (PDF). In Geoffrey P. Megargee; Martin Dean & Mel Hecker. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum encyclopedia of camps and ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. II, Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 180–184. ISBN 978-0-253-35599-7. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- ↑ Rovit & Goldfarb, p. 172.

- ↑ Karas (1985), pp. 13-15.

- ↑ Rovit & Goldfarb, p. 173.

- ↑ Karas (1985), p. 18.

- ↑ Karas (1985), pp. 11-14.

- ↑ Kramer (1998), p. 17.

- ↑ Kramer (1998), p. 21.

- ↑ Karas (1985), p. 100.

- ↑ Rovit & Goldfarb, pp. 193-194.

- ↑ Rovit & Goldfarb, pp. 197-198.

- ↑ Karas (1985), p. 102.

- ↑ Kramer (1998), p. 19.

- ↑ Kramer (1998), pp. 20-21.

- ↑ Kramer (1998), p. 22.

- ↑ Karas (1985), p. 35.

- ↑ Kramer (1998), pp. 15 & 17.

- ↑ "Theresienstadt: Red Cross Visit". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ↑ "This day in Jewish history / Filming in Theresienstadt". Haaretz Daily Newspaper Ltd. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich At War. Penguin. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-59420-206-3. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ↑ "David P. Boder Interviews Hildegarde Franz". Voices of the Holocaust. Munich, Germany. September 20, 1946. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ Willy Groag, "Socialni pece o mladez," YV, O7, 290.

- 1 2 3 4 National Archives WO 311/199, WO 309/377 Archived 2013-11-03 at the Wayback Machine., aifpow.com; accessed 24 September 2017.

- ↑ Winfried R. Garscha and Claudia Kuretsidis-Haider, "War Crime Trials in Austria" presented at the 21st Annual Conference of the German Studies Association (GSA) in Washington, D.C. (25–28 September 1997).

- ↑ Lang, Answer (2001). "Die Lagerkommandanten von Theresienstadt. Österreichische NS-Täter" [The Camp Commandants of Theresienstadt. Austrian Nazi perpetrators] (PDF) (in German). Retrieved 3 December 2011 – via textfeld.

- ↑ Karla Muller-Tupath, Verschollen in Deutschland. Vom heimlichen Leben des Anton Burger, Lagerkommandant in Theresienstadt, Hamburg 1994; ISBN 978-3894581329.

- ↑ The Trial of Adolf Eichmann, Session 45, nizkor.org; accessed 24 September 2017.

- ↑ State Regional Archive Litoměřice, MLS 441/47.

- Karas, Joza (1985). Music in Terezín 1941-1945 (1st ed.). New York: Beaufort Books. ISBN 0825302870. OCLC 11468415.

- Kramer, Aaron (1998). "Creative Defiance in a Death-Camp". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 38 (1).

- Redlich, Gonda (1992). Friedman, Saul S., ed. The Terezin Diary of Gonda Redlich. Trans. Laurence Kutler, foreword by Nora Levin. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1804-2.

- Rovit, Rebecca; Goldfarb, Alvin (1999). Theatrical performance during the Holocaust : texts, documents, memoirs. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801861675. OCLC 41173837.

Further reading

- Adler, H. G. Die verheimlichte Wahrheit, Theresienstaedter Dokumente, Tübingen: Mohr 1958.

- Adler, H. G. Theresienstadt, 1941–1945; das Antlitz einer Zwangsgemeinschaft. Geschichte, Soziologie, Psychologie. Tübingen, Mohr, 1955; second edition, 1960; reprint, Wallstein, Goettingen, 2005.

- Adler, H. G. Eine Reise. Eine Erzaehlung, bibliotheca christiana, Bonn, 1962; reprinted with an afterword by Jeremy Adler, Zsolnay Verlag, Vienna, 1999.

- Adler, H. G. The Journey, translated by Peter Filkins, Random House, New York, 2008.

- Bondy, Ruth. "Elder of the Jews": Jakob Edelstein of Theresienstadt, translated from the Hebrew 1989, ISBN 0-8021-1007-X'

- Brenner, Hannelore The Girls of Room 28: Friendship, Hope, and Survival in Theresienstadt ISBN 978-0-8052-4244-7

- De Silva, ed. In Memory's Kitchen: A Legacy from the Women of Terezin, translated by Bianca Steiner Brown, foreword by Michael Berenbaum, Jason Aronson, Inc., 1996, ISBN 1-56821-902-4

- Drexler, Paul In Search of My Father: The Journey of a Child Holocaust Survivor, ISBN 978-0-9805185-1-1

- Feuss, Axel. Das Theresienstadt-Konvolut, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-935549-22-9

- Friesova, Jana Renee. Fortress of My Youth: Memoir of a Terezín Survivor ISBN 0-299-17810-2

- Green, Gerald. The Artists of Terezin, New York: Hawthorn Books 1959.

- Giner, Bruno. Survivre et mourir en musique dans les camps nazis, Paris : Berg International, 2011

- Hajkova, Anna (6 May 2011). "The Piano Virtuoso Who Didn't Play in Terezín, or, Why Gender Matters". Orel Foundation. Retrieved 2012-05-13.

- Klíma, Ivan. "A Childhood in Terezin", Granta 44 (1993).

- Makarova, Elena. University over the Abyss Lectures in Ghetto Theresienstadt, Sergei Makarov & Victor Kuperman, ISBN 965-424-049-1

- Mandl, Herbert Thomas. Tracks to Terezín (Interview: Herbert Gantschacher; Camera: Robert Schabus; Edit: Erich Heyduck / DVD; Arbos, Vienna-Salzburg-Klagenfurt 2007)

- Manes, Philipp. As If It Were Life (A WWII Diary from the Theresienstadt Ghetto), Germany, 2009, ISBN 978-0-230-61328-7

- Milotova, Jaroslava; Hajkova (eds.). "Theresienstädter Studien und Dokumente – 1994–present (yearbook)" (in German). Retrieved 2012-05-13. (subscription required)

- Murmelstein, Benjamin. Terezin: Eichmann's Model Ghetto, 1961/reprint in Italian, 2013)

- Oppenhejm, Melanie. Theresienstadt: Survival in Hell, ISBN 1-874320-28-4

- Petit, Elise. "Musique, religion, résistance à Theresienstadt", online article in French

- Polak, Monique. "What World is Left" Orca book publishers, US 2008, ISBN 978-1-55143-847-4

- Rea, Paul. Voices from the Fortress: The Extraordinary Stories of Australia's Forgotten Prisoners of War (2007) ISBN 978-0-7333-2095-8

- Schiff, Vera. Theresienstadt: The Town the Nazis Gave to the Jews

- Schwertfeger, Ruth. Women of Theresienstadt, Oxford, Berg 1989.

- Sebald, W. G. Theresienstadt; excerpt from Austerlitz; Random House, NY 2001.

- Smith, Charles Saumarez (29 September 2001). "Another time, another place : A review of Austerlitz by W. G. Sebald". The Observer. Retrieved 2012-05-13.

- Volavkova, Hana, ed. ...I never saw another butterfly...:Children's Drawings and Poems from Terezin Concentration Camp 1942–1944, Schocken Books, 1993.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Theresienstadt concentration camp. |

- Terezin concentration camp, official website

- "Theresienstadt", About the Holocaust, Yad Vashem

- "Music and the Jewish Holocaust": Theresienstadt – The Model Camp, by Dr. Guido Fackler

- Beit Terezin, Theresienstadt Martyr's Remembrance Association at kibbutz Givat Haim Ihud, Israel

- The Archive of Holocaust, The Jewish Museum in Prague

- Pastimes: Numismatics, The New York Times

- The Genocide of the Czech Jews by Miroslav Karny

- A comprehensive discography of Musicians in Theresienstadt, Claude Torres website

- Guide to the Theresienstadt Collection, Leo Baeck Institute, New York City, New York

- Terezín, Czech Republic at JewishGen