The Holocaust in Italy

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Period | September 1943 – May 1945 |

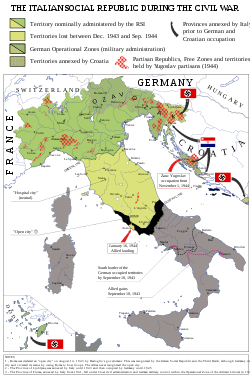

| Territory | Italian Social Republic |

| Major perpetrators | |

| Units | SS-TotenkopfverbändeEinsatzgruppenFascist Italian Police |

| Victims | |

| Killed | 8,000 |

| Pre-war population | 40,000 |

The Holocaust in Italy was the persecution, deportation, and murder of Jews between 1943 and 1945 in the Italian Social Republic, the part of the Kingdom of Italy occupied by Nazi Germany after the Italian surrender on 8 September 1943, during World War II.

Up to the Italian surrender, Italy and the Italian occupation zones in Greece, France and Yugoslavia had been a place of relative safety for local Jews and European Jewish refugees. This however changed in September 1943, when German forces occupied the country, installed a puppet regime and immediately began persecuting and deporting the Jews in the country. Italy had a pre-war Jewish population of 40,000 but, through evacuation and refuges, this number actually increased during the war. Of the estimated close to 50,000 Jews living in Italy before September 1943, an estimated 8,000 died during the Holocaust, while 40,000 survived. In this, the Italian police and Fascist militia played a vital part as German accessories.

While most Italian concentration camps where police and transit camps, one camp, the Risiera di San Sabba in Trieste, was also an extermination camp and it is estimated that up to 5,000 prisoners, mostly political, were murdered there.

The Holocaust in Italy has received comparatively little attention and, for example, up to the 1990s, no publication dealt with the history of the Italian concentration camps.[1]

Situation prior to 8 September 1943

Italian Jews suffered far less persecution in Fascist Italy than the Jews in Nazi Germany did in the lead up to World War II. In the territories occupied by the Italian Army in Greece, France and Yugoslavia after the outbreak of World War II Jews even found protection from persecution.[2] Under the Italian Racial Laws of 1938, Jews lost their civil rights, including to property, education, and employment. Unlike Jews in other Axis-aligned countries, they were not murdered or deported to extermination camps.[3][4] The persecution of Jews in Italy between 1938 and 1943 has received only very limited attention in the Italian public.[4] Lists of Jews drawn up to enforce the racial laws were used after the Italian surrender on 8 September 1943 to round them up.[5]

No Jews in Italy or Italian-occupied areas were deported to concentration camps in Germany before September 1943. The Italian Army actively protected Jews in occupation zones, to the frustration of Nazi Germany, and to the point where the Italian sector in Croatia was referred to as the "Promised Land".[6]

The Fascist Italian government opened 50 concentration camps after its entry into the war, predominantly to hold political prisoners but also around 2,200 Jews of foreign nationality. The Jews in these camps were treated no different from political prisoners and, while living conditions and food were often basic, prisoners were not treated with violence. Much worse however were the conditions for imprisoned Roma, which, the Italian authorities perceived, were used to a harsh life and therefore received much lower allowances in food and more basic accommodation.[7] After the occupation of Greece and Yugoslavia in 1941 Italy, also opened concentration camps in its occupation zones there, which held a total of up to 150,000 people and in which the living conditions were very harsh. The mortality rate in these camps far exceeded the ones in the Italian camps.[8]

On 25 July 1943, with the fall of the Fascist Regime, the situation in the camps changed, with inmates gradually released, including Jewish prisoners. This process was however not completed by the time German authorities took over the camps in September.[8]

Germany, up to September 1943, made no serious attempt to force Mussolini and Fascist Italy into handing over the Italian Jews but was nevertheless irritated with the Italian refusal to arrest and deport its Jewish population as it felt it thereby encouraged other countries allied with the Axis powers to refuse as well.[9]

The Holocaust in Italy

Organisation

Tasked with overseeing SS operations and, thereby, the final solution, the genocide of the Jews, was SS-Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff, who was appointed as the Highest SS and Police leader in Italy. Wolff assembled a group of SS personnel under him that had a vast experience in the extermination of Jews in Eastern Europe. Odilo Globocnik, appointed as police leader for the coastal area, was responsible for the murder of hundreds of thousands of Jews and Gypsies in Lublin, Poland, before being sent to Italy.[10] Karl Brunner was appointed as SS and police leader in Bolzano, South Tyrol, Willy Tensfeld in Monza for upper and western Italy and Karl-Heinz Bürger was placed in charge of anti-partisan operations.[11]

The security police and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) came under the command of Wilhelm Harster, based in Verona, who had previously held the same position in the Netherlands.[12] Theodor Dannecker, previously active in the deportation of Greek Jews in the part of Greece occupied by Bulgaria, was made chief of the Judenreferat of the SD and was tasked with the deportation of the Italian Jews. Not seen as efficient enough, he was replaced by Friedrich Boßhammer, who was, like Dannecker, closely associated with Adolf Eichmann.[13][14]

Martin Sandberger was appointed as the head of the Gestapo in Verona and played a vital role in the arrest and deportation of the Italian Jews.[5]

As in other German-occupied areas and in the Reich Main Security Office itself, the persecution of minorities undesired by the Nazis and political opponents fell under section IV of the Security Police and SD. Section IV, in turn, was subdivided into further departments, of which department IV–4b was responsible for Jewish affairs. Dannecker, then Boßhammer headed this department.[15]

The Congress of Verona

The attitude of the Italian Fascists towards Italian Jews drastically changed in November 1943, after the Fascist authorities declared them to be of "enemy nationality" during the Congress of Verona and begun to actively participate in the prosecution and arrest of Jews.[16] Initially, after the Italian surrender, the Italian police had only assisted in the round up of Jews when requested to do so by the German authorities. With the Manifest of Verona, in which Jews were declared to be foreigners and, in times of war, enemies, this changed. Police Order No. 5 on 30 November 1943, issued by the minister of the interior of the RSI Guido Buffarini Guidi, ordered the Italian police to arrest Jews and confiscate their property.[17][18] This order however exempt Jews over the age of 70 or of mixed marriages, to the frustration of the Germans who wanted to arrest and deport all Italian Jews.[8]

Deportation and murder

The arrest and deportation of Jews in German-occupied Italy can be separated into two distinct phases, an initial one under Dannecker from September 1943 to January 1944, where mobile Einsatzkommandos targeted the Jews of major Italian cities, and a second phase under Boßhammer, who had replaced Dannecker in early 1944. Boßhammer set up a centralised persecution system, using all available resources of the German and Fascist Italian police to arrest and deport the Italian Jews.[5][19]

The arrest of Jewish Italians and Jewish refuges began almost immediately after the surrender, in October 1943, taking place in all the major Italian cities under German control, albeit with limited success. The Italian police only offered limited cooperation and, in Rome, ninety percent of the city's 10,000 Jews escaped arrest. The arrested Jews were taken to the transit camps at Borgo San Dalmazzo, Fossoli and Bolzano and, from there, to the Auschwitz. Of the 4,800 deported from there only 314 survived.[20] Approximately half of all Jews arrested during the Holocaust in Italy were arrested by the Italian police.[21]

A few hundred Libyan Jews, an Italian colony before the war, who had been deported to mainland Italy in 1942, were sent to Bergen-Belsen instead. Most of those held British and French citizenship and most survived the war.[20]

Altogether, almost 8,600 Jews from Italy and Italian-controlled areas in France and Greece were deported to Auschwitz of which all but 1,000 were murdered. A further 300 Jews were shot or died in transit camps in Italy of other causes.[20]

Of those executed in Italy, almost half were killed at the Ardeatine massacre in March 1944 alone,[20] while the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler killed over 50 Jewish civilians, refugees and Italian nationals, at the Lake Maggiore massacres, the first massacres of Jews by Germany in Italy during the war, committed immediately after the Italian surrender, and sunk the bodies in the lake.[22] This was done despite strict orders at the time not commit any violence against the civilian population.[23]

In the 19 month of German occupation, from September 1943 to May 1945, twenty percent of Italy's pre-war Jewish population was killed by the Nazis.[24] The actual Jewish population in Italy during the war was however higher than the initial 40,000 as the Italian government had evacuated 4,000 Jewish refuges from its occupation zones to southern Italy alone. By September 1943, 43,000 Jews were present in northern Italy and, by the end of the war, 40,000 Jews in Italy had survived the Holocaust.[20]

Romani people

Unlike Italian Jews, the Romani people had faced discrimination by Fascist Italy almost from the start of the regime. In 1926 it ordered that all "foreign Gypsies" should be expelled from the country and, from September 1940, Romani people of Italian nationality were held in designated camps. With the start of the German occupation many of these camps came under German control. The impact the German occupation had on the Romani people in Italy has seen little research and the number of Romani that died in Italian camps or were deported to concentration camps is uncertain.[25]

The number of Romani people that died from hunger and exposure during the Fascist Italian period is also unknown but is estimated to go into the thousands.[26]

While Italy observes the 27 January as a Remembrance Day for the Holocaust and its Jewish Italian victims efforts to extend this official recognition to the Italian Romani people killed by the Fascist regime or deported to extermination camps have been rejected.[27]

Role of the Catholic Church and the Vatican

Before the Raid of the Ghetto of Rome Germany had been warned that such an action could raise the displeasure of Pope Pius XII but the pope never spoke out against the deportation of the Jews of Rome during the war, something that has sparked controversy. At the same time, members of the Catholic Church provided assistance to Jews and helped them survive the Holocaust in Italy.[5]

Camps

German and Italian run transit camps for Jews, political prisoners and forced labour existed in Italy:[28]

- Bolzano camp, located in the Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol region, part of the Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills at the time, operating as a German-controlled transit camp from summer 1944 to May 1945.[29][30]

- Borgo San Dalmazzo camp, located in the Piedmont region, operating as a German-controlled transit camp from September 1943 to November 1943 and, under Italian control, from December 1943 to February 1944.[31][32]

- Fossoli camp, located in the Emilia-Romagna region, operating as a prisoner of war camp under Italian control from May 1942 to September 1943, then as a transit camp, still under Italian control until March 1944 and, from then until November 1944 under German control.[33]

Apart from those three transit camps Germany also operated the Risiera di San Sabba camp, located in Trieste, then part of the Operational Zone of the Adriatic Littoral, which simultaneously functioned as an extermination and transit camp. It was the only extermination camp in Italy during World War II and operated from October 1943 to April 1945, with up to 5,000 people killed there,[34][35] with most of those being political prisoners.[20]

Additionally to the designated camps, Jews and political prisoners were also held at common prisons, like the San Vittore Prison in Milan, which gained notoriety during the war through the inhumane treatment of inmates by the SS guards and the torture carried out there.[36] From San Vittore Prison, which served as transit station for Jews arrested in northern Italy, the prisoners would be taken to Milano Centrale railway station, where they would be loaded into freight cars on a secret track underneath the station and deported.[21]

Looting of Jewish property

Apart from the extermination of the Jews, Nazi Germany was also extremely interested in appropriating Jewish property. An estimate set the value of Jewish property looted in Italy during the Holocaust, between 1943 and 1945, at US$1 billion in 2010 value.[4]

Among the most priceless artifects lost this way are the contents of the Biblioteca della Comunità Israelitica and the Collegio Rabbinico Italiano, the two Jewish libraries in Rome. Of the former, all content continues to be missing while of the latter, some parts were returned after the war.[37]

Weeks before the Raid of the Ghetto of Rome, Herbert Kappler forced the Jeish community of Rome to hand over 50 kilogram of gold in exchange for safety. Despite the community doing so on 28 September 1943, over 1,000 of its members were arrested on 16 October and deported to Auschwitz where all but 16 died.[38]

Perpetrators

Very few perpetrators of the Holocaust in Italy, German or Italian, were tried or jailed after the war.[20]

Post-war trials

Of the war crimes committed by the Nazis in Italy the Ardeatine massacre saw arguably the most perpetrators convicted. High-ranking Wehrmacht officials Albert Kesselring, Field Marshal and commander of all Axis forces in the Mediterranean theatre, Eberhard von Mackensen, commander of the 14th German Army and Kurt Mälzer, military commander of Rome, where all sentenced to death but pardoned and released in 1952, except Mäler who died before he could be released. Of the perpetrators from the SS, police chief of Rome Herbert Kappler was sentenced in 1948 but latter escaped jail while Erich Priebke and Karl Hass long escaped justice but were eventually tried in 1997.[39]

Theodor Dannecker, in charge of the Judenreferat in Italy, committed suicide after being captured in December 1945, thereby avoiding a possible trial,[13] while his successor, Friedrich Boßhammer, disappeared at the end of the war in 1945 and subsequently worked as a lawyer in Wuppertal. He was arrested in West Germany in 1968 and eventually sentenced to life in prison for his involvement in the deportation of 3,300 Jews from Italy to Auschwitz. During the Holocaust almost 8,000 of the 45,000 Jews living in Italy perished.[40] During his trial over 200 witnesses were heard before he was sentenced in April 1972. He died a few month after the verdict without having spend any time in prison.[14][41]

Karl Friedrich Titho's role as camp commander at the Fossoli di Carpi Transit Camp and the Bolzano Transit Camp in the deportation of Jewish camp inmates to Auschwitz was investigated by the state prosecutor in Dortmund, Germany, in the early 1970s but the investigation was eventually terminated. The investigation was officially terminated on the grounds that it could not be proven that Titho knew that the Jews deported to Auschwitz would be killed there and that, given the late state of the war, they were killed at all. He was also tried for the execution of 67 prisoners as reprisal for a partisan attack but it was ruled that it did not classify as murder but, at the most, as man slaughter and the charge had therefore reach the statute of limitation. The two heads of the department investigating Titho had both been members of the Nazi Party from an early date.[42]

In 1964, six members of the Leibstandarte division were charged with the Lago Maggiore massacre, carried out near Meina, as the statute of limitation laws in Germany at the time, twenty years for murder, meant that the perpetrators could soon not be prosecuted anymore. All of the accused were found guilty and three received a live sentence for murder while two others received a jail sentence of three years for having been accessories in the murder, while the sixth one died during the trial. The sentence was appealed and Germany's highest court, the Bundesgerichtshof, ruled that, while not overturning the guilty verdict, that the perpetrators had to be freed on a technicality. As the crime had been committed in 1943 and was actually investigated by the division already back then, also without a conclusion, the usual start date for statute of limitations for Nazi crimes, the date of the German surrender in 1945, did not apply, meaning the 1943 massacre's statute of limitations had been expired.[43][23]

This verdict caused much frustration in Germany with a younger generation of state prosecutors which were actually interest in prosecuting Nazi crimes and their perpetrators. The verdict by the Bundesgerichtshof had further reprocusions as it ruled that perpetrators could only be charged with murder if direct involvement in killing could be proven. In any other cases the charge could only be manslaughter which meant, after 1960, by German law, the statute of limitations for these crimes had expired.[43]

Germany did however remove the statute of limitations for murder in 1969 altogether, allowing direct murder charges to be prosecuted indefinitely but even there this was not always applied to Nazi war crimes which were judged by pre-1969 laws, like in the case of Wolfgang Lehnigk-Emden who escaped a jail sentence despite having been found guilty in the case of the Caiazzo massacre.[44]

Italian role in the Holocaust

The role of Italians as collaborators of the Germans in the Holocaust in Italy has rarely been reflected on in the country after World War II. A 2015 book by Simon Levis Sullam, a professor of modern history at the Ca' Foscari University of Venice, titled The Italian Executioners: The Genocide of the Jews of Italy examined the role of Italians in the genocide and found that half of the Italian Jews killed in the Holocaust were arrested by Italians rather than Germans and that many arrests could only be carried out because of tip-offs by civilians. Sullam argued that Italy ignored what he called its "era of the executioner", rehabilitated Italian participants in the Holocaust through a 1946 amnesty and continued to focus on its role as saviours of the Jews rather than to reflect on the persecution Jews suffered in Fascist Italy.[45]

Michele Sarfatti, one of most important historians of Italian Jewry in the country, stated his believe that, up until the 1970s, Italians generally believed their country was not involved in the Holocaust and that instead it was exclusively the work of the German occupiers. This only began to change in the 1990s, after the publication of Il Libro Della Memoria by Jewish Italian historian Liliana Picciotto and the publication of the Italian Racial Laws in book form in the early 2000s, with the latter highlighting the fact that Italy's anti-semitic laws were distinctly independent from the ones in Nazi Germany and, in some instances, more severe than the early anti-semitic laws Germany had issued.[21]

Commemoration

Memoriale della Shoah

The Memoriale della Shoah is a Holocaust memorial in Milano Centrale railway station, dedicated to the Jewish people deported from there from a secret platform underneath the station to the extermination camps and was opened in January 2013.[36][21]

Borgo San Dalmazzo camp

No trace now remains of the former Borgo San Dalmazzo concentration camp but two epitaphs were erected to mark the events that took place in Borgo San Dalmazzo. In 2006 a memorial was erected at the Borgo San Dalmazzo railway station to commemorate the deportations. The memorial contains the names, ages and countries of origin of the victims as well as those of the few survivors, as well as some freight cars of the type used in the deportation.[31][32][28]

Fossoli Camp

In 1996 a foundation was formed to preserve the former camp. From 1998 to 2003 volunteers rebuilt the fencing around the Campo Nuovo and, in 2004, one of the barracks that used to house Jewish inmates was reconstructed.[28]

Italian Righteous Among the Nations

As of 2018, 694 Italians have been recognised as Righteous Among the Nations, an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination by the Nazis.[46]

The first Italians to be honoured in this fashion were Don Arrigo Beccari, Doctor Giuseppe Moreali and Ezio Giorgetti in 1964.[47] Arguably the most famous of those is cyclist Gino Bartali, winner of the 1938 and 1948 Tour de France, who was honoured for his role in saving Italian Jews during the Holocaust in 2014, never having spoken about it during his lifetime.[48]

In literature

Primo Levi, an Italian Jewish Auschwitz survivor, published his experience of the Holocaust in Italy in his books If This is a Man and The Periodic Table.

References

- ↑ Megargee 2012, p. 393.

- ↑ Gentile, p. 10.

- ↑ Philip Morgan (10 November 2003). Italian Fascism, 1915-1945. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-230-80267-4.

- 1 2 3 Vitello, Paul (4 November 2010). "Scholars Reconsidering Italy's Treatment of Jews in the Nazi Era". New York Times. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "The destruction of the Jews of Italy". The Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ↑ McGrory, Mary (2 December 1993). "Italy's heroes of the Holocaust". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ↑ Megargee 2012, pp. 391.

- 1 2 3 Megargee 2012, p. 392.

- ↑ Peter Longerich. Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. p. 396.

- ↑ Gentile, p. 4.

- ↑ Gentile, p. 5.

- ↑ Gentile, p. 6.

- 1 2 "Dannecker, Theodor (1913–1945)" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- 1 2 "Boßhammer, Friedrich (1906–1972)" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Gentile, pp. 6–8.

- ↑ Gentile, p. 15.

- ↑ "Jews in Italy Under Fascist and Nazi Rule, 1922-1945". Google books. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ↑ "The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos". Google books. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ↑ "Judenverfolgung in Italien" [Persecution of Jews in Italy] (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Italy". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Bridget Kevane (29 June 2011). "A Wall of Indifference: Italy's Shoah Memorial". The Jewish Daily Forward.com. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Gentile, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 "Bundesgerichtshof Urt. v. 17.03.1970, Az.: 5 StR 218/69" [German High Court verdict from 17 March 1970] (in German). 17 March 1970. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ↑ "The "Final Solution": Estimated Number of Jews Killed". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ Giovanna Boursier. "Project Education of Roma Children in Europe: The Nazi Periodin Italy" (PDF). Council of Europe. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ McGrory, Mary (27 June 2008). "Plight of the Roma: echoes of Mussolini". The Independent. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Riccardo Armillei. "The 'Camps System' in Italy". Google books. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Der Ort des Terrors: Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager Bd. 9: Arbeitserziehungslager, Durchgangslager, Ghettos, Polizeihaftlager, Sonderlager, Zigeunerlager,Zwangsarbeitslager" (in German). Wolfgang Benz, Barbara Distel. 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "BOLZANO". ANED – National Association of Italian political deportees from Nazi concentration camps. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "Bozen-Gries" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- 1 2 "BORGO SAN DALMAZZO". ANED – National Association of Italian political deportees from Nazi concentration camps. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- 1 2 "BORGO SAN DALMAZZO" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "FOSSOLI". ANED – National Association of Italian political deportees from Nazi concentration camps. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "SAN SABBA RICE MILL". ANED – National Association of Italian political deportees from Nazi concentration camps. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "Risiera San Sabba" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- 1 2 "Mailand" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ↑ "Activity Report of the Commission for the Recovery of the Bibliographic Heritage of the Jewish Community in Rome, looted in 1943". The Central Register of Information on Looted Cultural Property. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ "Ghetto Rom" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ "ARDEATINE CAVES MASSACRE". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ↑ "The Jews of Italy". The Museum of The Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ↑ "EX‐NAZI GETS LIFE IN IT ALIANS' DEATHS". New York Times. 12 April 1972. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Schwarzer, Marianne (17 February 2016). "Dem "Henker von Fossoli" blieb ein Prozess auf deutschem Boden erspart" [The „Executor of Fossoli“ is spared from a trial on German soil]. Lippische Landes-Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- 1 2 Kellerhoff, Sven Felix (7 January 2008). "Fünf SS-Verbrecher werden angeklagt" [Five SS criminals put on trial]. Die Welt (in German). Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ↑ Williams Walsh, Mary (2 March 1995). "Ex-Nazi in War Crimes Case Freed on Technicality". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ↑ Lebovic, Matt (13 August 2018). "Italy's Holocaust executioners revealed in 'historiographical counterblast". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ↑ "Names of Righteous by Country". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ "Names of Righteous by Country: Italy" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ Peter Crutchley (9 May 2014). "Gino Bartali: The cyclist who saved Jews in wartime Italy". BBC News. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

Bibliography

- Gentile, Carlo. The Police Transit Camps in Fossoli and Bolzano - Historical report in connection with the trial of Manfred Seifert. Cologne.

- Megargee, Geoffrey P., ed. (2012). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945 - Volume III - Camps and Ghettos under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany. in association with United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02373-5.