Flossenbürg concentration camp

| Flossenbürg concentration camp | |

|---|---|

| Labor camp | |

Main gate of the camp | |

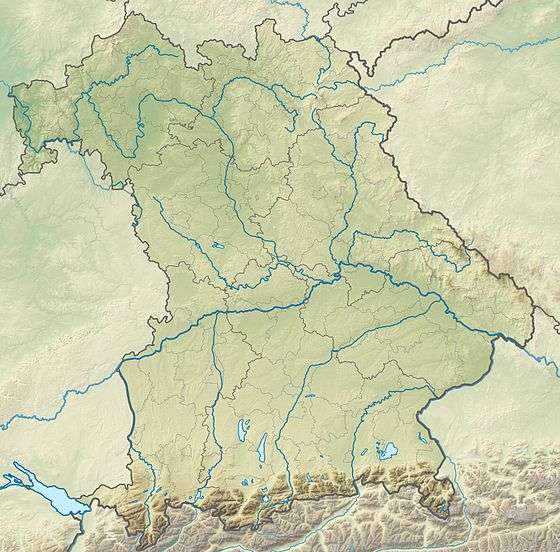

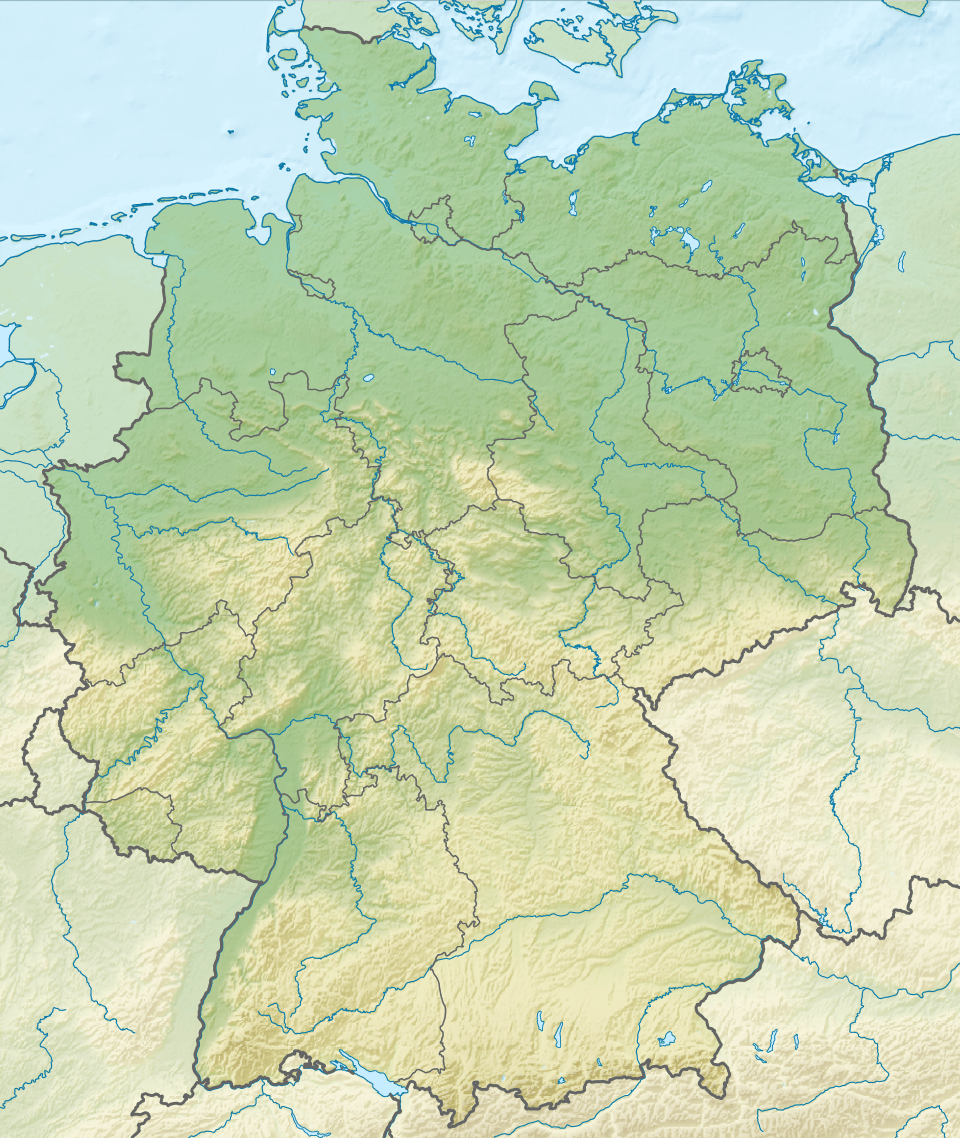

Location of Flossenbürg concentration camp within Bavaria  Flossenbürg concentration camp (Germany) | |

| Location | Flossenbürg, Germany |

| Built by | SS-WHVA |

| Operated by | Nazi Germany |

| Commandant |

List

|

| Operational | May 1938-23 April 1945 |

| Inmates | Political prisoners, Jews, criminals, antisocials |

| Number of inmates | 89,974 |

| Killed | 30,000 |

| Liberated by | US Army, 23 April 1945 |

| Notable inmates |

Executed: |

| Notable books | The Men With the Pink Triangle |

| Website |

www |

Flossenbürg concentration camp (German: Konzentrationslager Flossenbürg) was a Nazi concentration camp built in May 1938 by the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office at Flossenbürg, in the Upper Palatinate region of Bavaria, Germany, near the border with Czechoslovakia. Until its liberation in April 1945, 89,964 prisoners passed through the camp, around 30,000 of whom died there.[1]

History

Before World War II, Flossenbürg was a camp exclusively for German "antisocial" or "criminal" prisoners. The camp's site was chosen so that the inmates could be used as slave labor to quarry the granite found in the nearby hills. The quarries belonged to the SS-owned and -operated German Earth and Stone Works (DEST) company. On 24 March 1938, SS authorities determined a site near the small town of Flossenbürg to be suitable for the establishment of a concentration camp due to its potential for extracting granite for construction purposes.[1]

The inmates in Flossenbürg were housed in 16 wooden barracks. A crematorium to dispose of the dead was built in a valley straight outside the camp. In September 1939, the SS transferred 1,000 political prisoners to Flossenbürg from Dachau, but moved them back to Dachau in March. There were over 4,000 prisoners in the main camp of Flossenbürg in February 1943. More than half of these prisoners were political prisoners (mainly Soviet, Czech, Dutch, and German). Almost 800 were German criminals, more than 100 were homosexuals, and 7 were Jehovah's Witnesses. Continuing influxes of political prisoners from occupied countries caused Germans to become a minority that same year.[1]:561

In 1944, the camp continued to receive a high influx of mainly non-German prisoners. The main camp, situated in a narrow valley, had little room for expansion. Originally constructed for only 1,500 prisoners, the population of the main camp increased to almost 10,000 before it was evacuated in April 1945. In order to increase productivity, the prisoners were forced to sleep and work in shifts. This also helped alleviate the chronic overcrowding in the barracks. Prisoners also suffered from a shortage of fresh water, due to the elevation, and unusually cold and wet weather.[1]

On 1 September 1944, Flossenbürg became a training camp for extremely large numbers of female guards (Aufseherinnen) who were recruited by force from factories all over Germany and Poland. All together, over 500 women were trained in the camp and in time went on to its subcamps. Women matrons staffed the Flossenbürg subcamps, such as Dresden Ilke Werke, Freiberg, Helmbrechts, Holleischen, Leitmeritz, Mehltheuer, Neustadt (near Coburg), Nürnberg-Siemens, Oederan, and Zwodau, and it is known that six SS women (SS-Helferinnenkorps) staffed the Gundelsdorf subcamp in Czechoslovakia.

By 1945, there were almost 40,000 inmates held in the whole Flossenbürg camp system, including almost 11,000 women. Malnutrition, diseases, and overwork were rife among the inmates. Combined with the harshness of the guards, this deliberate maltreatment killed many thousands of inmates.[2] As a result of the evacuation of eastern camps, the population peaked in March 1945, with 53,000 prisoners.[1]

Forced labor

The camp was originally founded for the exploitation of prisoner labor in quarries for civilian projects. During the war, prisoner forced labor became increasingly important in German arms production. As a result, the Flossenbürg camp system expanded to include approximately 100 subcamps concentrated mainly around armaments industries in southern Germany and western Czechoslovakia.[1]:560

In January 1943, as part of an effort to increase fighter aircraft production, Messerschmitt AG licensed an SS-owned company, DEST, to manufacture Messerschmitt Bf 109 parts at Flossenbürg using the expertise of Messerschmitt engineers and the labor of inmates. Because the prisoners were not paid, the enterprise was highly profitable for both Messerschmitt and the SS.[3] By August 1943, 800 prisoners worked for Messerschmitt; a year later, 5,700 prisoners were employed in armaments production.[1]

Executions

In 1941 to 1942, about 1,500 Polish prisoners, mostly members of the Polish resistance, were deported to Flossenbürg. In July 1941, SS guards shot 40 Polish prisoners at the SS firing range outside the Flossenbürg concentration camp. Between February and September 1941 the SS executed about one-third of the Polish political prisoners deported to Flossenbürg.

During World War II, the German army turned tens of thousands of Soviet prisoners over to the SS for execution. More than 1,000 Soviet prisoners of war were executed in Flossenbürg by the end of 1941. The SS also established a special camp for Soviet prisoners of war within Flossenbürg. Executions of Soviet prisoners of war continued sporadically through 1944. Soviet prisoners of war in Mülsen St. Micheln, a subcamp of Flossenbürg, staged an uprising and mass escape attempt on 1 May 1944. They set their bunks on fire and killed some of the camp's Kapos - prisoner trustees who carried out SS orders. SS guards crushed the revolt and none of the prisoners escaped. Almost 200 prisoners died from burns and wounds sustained in the uprising. The SS transferred about 40 leaders of the revolt to Flossenbürg itself, where they were later executed in the camp jail.

It is estimated that between April 1944 and April 1945, more than 1,500 death sentences were carried out there. To this end, six new gallows hooks were installed. In the last months the rate of daily executions overtook the capacity of the crematorium. As a solution, the SS began stacking the bodies in piles, drenching them with gasoline, and setting them alight. Incarcerated in what was called the "Bunker," those who had been condemned to death were kept alone in dark rooms with no food for days until they were executed.

Amongst the Allied military officers executed at Flossenbürg were Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent Gustave Daniel Alfred Biéler (executed 6 September 1944). As American forces neared, a number of the SOE agents whom the SS had tortured repeatedly in order to extract information, were executed on the same day. On 29 March 1945, 13 SOE agents were hanged, including Jack Agazarian. In early April, the SS staged a perfunctory "trial" and executed General Hans Oster, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, Rev. Dr. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Dr. Karl Sack, Dr. Theodor Strünck and General Friedrich von Rabenau, who were involved in the 20 July plot against Adolf Hitler or previous plots against Hitler, along with the French Resistance worker Simone Michel-Lévy, who had tried to organize an uprising in the camp.

Death march and liberation

On 20 April 1945, the SS began the forced evacuation of 22,000 inmates, including 1,700 Jews, leaving behind only those too sick to walk. On the death march to the Dachau concentration camp, SS guards shot any inmate too sick to keep up.[4] Before they reached Dachau, more than 7,000 inmates had been shot or had collapsed and died.

Troops from the 2nd Cavalry Group, Mechanized, the 90th Infantry Division and the 97th Infantry Division[5][6] found about 1,600 ill and weak prisoners, mostly in the camp's hospital barracks. Members of the army's Counter-Intelligence Corps, including Ib Melchior,[7] Anthony Hecht[8] and Robie Macauley,[9] conducted extensive interviews with survivors to gather evidence for the 1946 Flossenbürg War Crimes Trial.

Aftermath

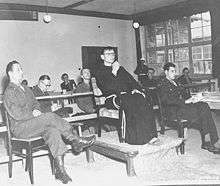

Flossenbürg Trial

The Flossenbürg War Crimes Trial took place in Dachau, Germany, from 12 June 1946 until 22 January 1947. An American military tribunal tried 46 former staff from Flossenbürg concentration camp for crimes of murder, torture, and starving the inmates in their custody. All but five of the defendants were found guilty. 15 were condemned to death, 11 were given life sentences, and 14 were jailed for terms of 1 to 30 years.

Holocaust museum

On 22 July 2007, the sixty-second anniversary of the camp's liberation, a Holocaust museum was opened at Flossenbürg. The ceremony was attended by 84 former inmates, in addition to the president of Ukraine, Viktor Yushchenko, whose father was among the camp's inmates during World War II for five months.[10] On 1 August 2007, a memorial was unveiled at Flossenbürg to the memory of the seven members of the German resistance who had conspired to assassinate Hitler and who were executed on 9 April 1945.

Since 2016, a digital book of the dead is available online and contains the names of more than 21,000 known prisoners who perished in the concentration camp[11]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 USHMM (2009). Megargee, Geoffrey P., ed. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. 1. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- ↑ Joseph A. Rehyansky, "Flossenburg," National Review, 25 June 1976, pp. 678–9.

- ↑ "Messerschmitt GmbH Regensburg". www.mauthausen-memorial.org. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ Fischer, Benno. Death March: April 15, 1945 - April 24, 1945. United States Holocaust Museum Media Archive, RG-02.039. Republished as "Death March," edited by Peter Heigl, Nuremberg, 2011.

- ↑ "Robert W. Hacker, "Knocking the Lock Off the Gate at the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp; April 23, 1945," excerpted from Robert W. Hacker: Flossenbürg Concentration Camp, Phoenix 2000, unpublished manuscript. Flossenbürg memorial archive". 97thdivision.com. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ "Memories of the chaplain to the US 97th Infantry Division at the online Museum of the division in WWII". 29 May 2011.

- ↑ Ib Melchior . "Ib Melchior, ''Case By Case: A U.S. Army Counterintelligence Agent in World War II,''". IUniverse (June 14, 2000). ISBN 0-595-00393-1. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ "Anthony Hecht, obituary". Breakoutofthebox.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ Macauley R. "Who Should Mourn?" The New York Times, Letters to the Editor, August 8, 1976.

- ↑ "Flossenbürg Memorial", Dateline World Jewry, World Jewish Congress, September 2007

- ↑ "Neues Mahnmal für ermordete Sinti und Roma im »Tal des Todes« der KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg". www.sonntagsblatt.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-01-26.

Literature

- Cziborra, Pascal (2007). KZ Flossenbürg : Gedenkbuch der Frauen. : Memorial Book of the Women. Bielefeld: Lorbeer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938969-03-8.

- Snyder, Timothy D. (2015). Black Earth. The Holocaust As History and Warning. ISBN 978-1-101-90346-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flossenbürg concentration camp. |

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia article, ushmm.org

- Flossenbürg camp prisoner testimonies page, 041940.pl

- Search the dead online by name

Coordinates: 49°44′08″N 12°21′21″E / 49.73556°N 12.35583°E